Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Perovskite-Polymer Composite

2.1. CsPbBr3−PMMA Composite

2.2. Ru-Based Perovskites/RGO Composite

| Synthesis Technique | Specific Capacitance (Fg-1) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal | 1585 | [54] |

| Laser scribing method | 1140 | [55] |

| Sol-gel and low temperature annealing | 570 | [56] |

| Solution phase assembly | 480 | [57] |

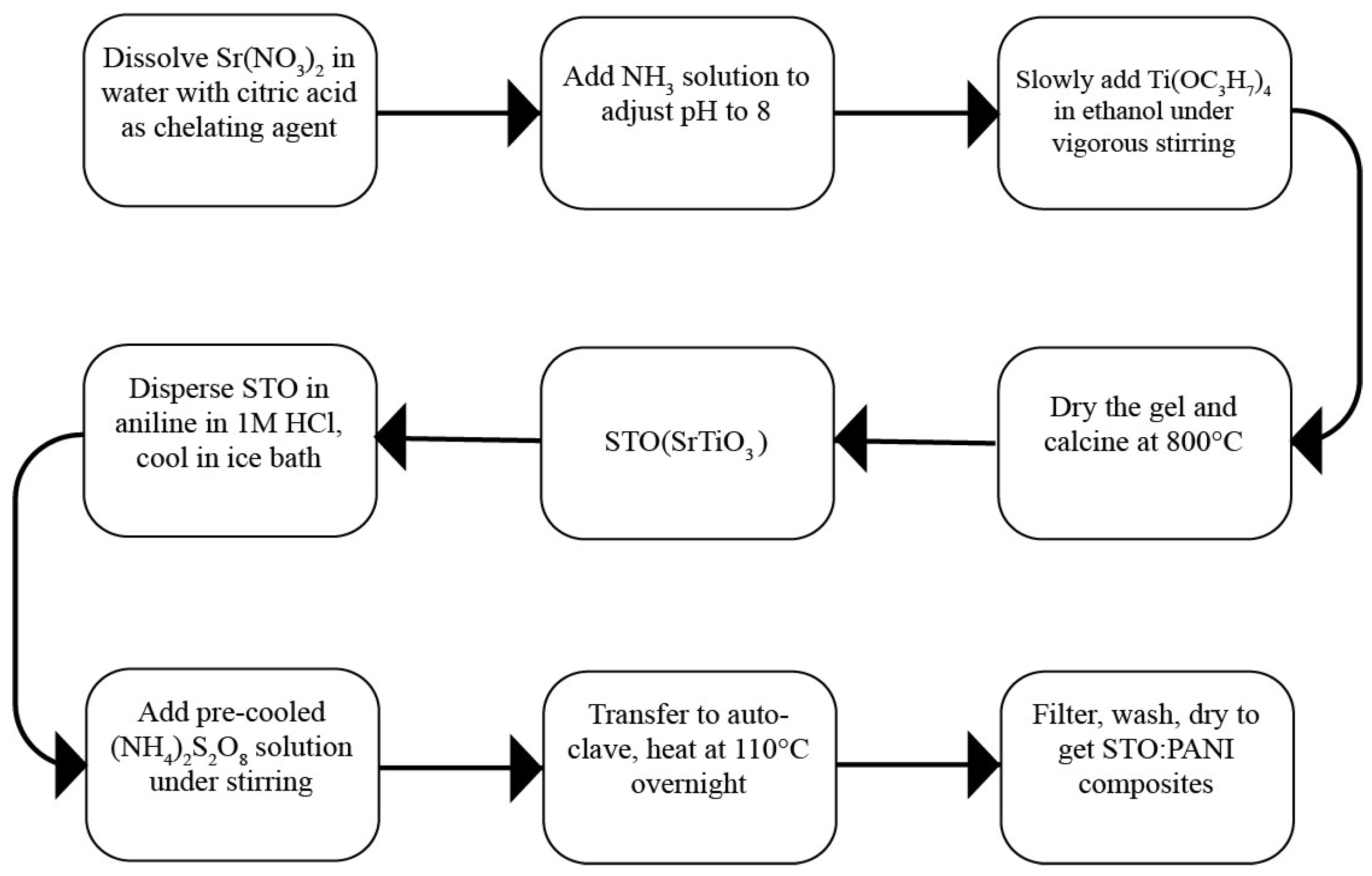

2.3. STO:PANI Composite

2.4. KCuCl3/PANI Composites

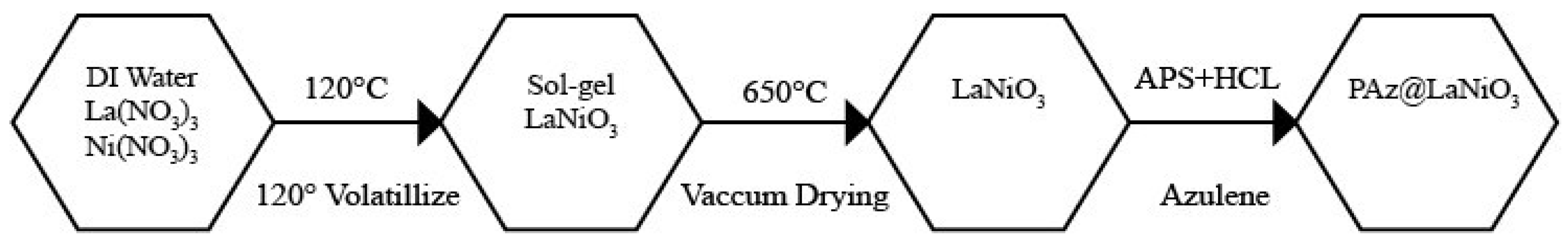

2.5. LaNiO3-PAz Composite

2.6. MBI: CPH-G Composite

| Scan Rate (V s-1) | Specific Capacitance under Dark (F g-1) |

Specific Capacitance under Light (F g-1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.35 | 4.96 | |

| 0.02 | 0.26 | 3.72 | |

| 0.05 | 0.19 | 2.48 | [99] |

| 0.1 | 0.15 | 1.65 | |

| 0.2 | 0.11 | 0.94 | |

| 0.5 | 0.09 | 0.23 |

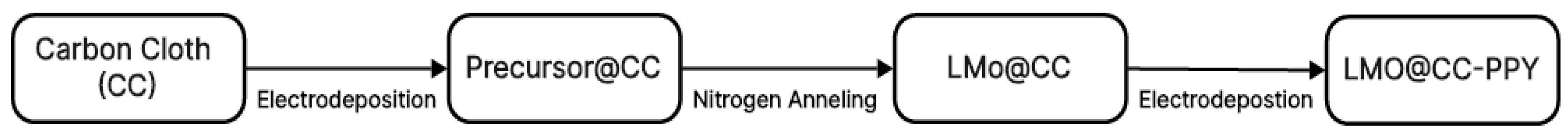

2.7. LaMnO3@CC-PPy Composite

2.8. Cs2AgBiBr6-PEDOT: PSS composite

| Composites | Specific Capacitance (Fg-1) | Current Desnisty (A g-1) | Stability | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr3- PMMA | 528 | 100 | 10,000 | [28] |

| RuO2/RGO | 480-1365 | 11 | 4000 | [48] |

| STO: PANI | 602 | 1 | 1500 | [73] |

| KCuCl3/PANI | 2434 | 0.2 | 3000 | [40] |

| LaNiO3-PAz | 464 | 2 | 3000 | [90] |

| LaMnO3@CC- PPy | 862 | 1 | 3000 | [109] |

| Cs2AgBiBr6-PEDOT:PSS | 633.5 | 0.5 | 10000 | [27] |

3. Current Situation and Future Research on Perovskite-Polymer Composites

4. Conclusions

References

- Raza, W.; Ali, F.; Raza, N.; Luo, Y.; Kim, K.-H.; Yang, J.; Kumar, S.; Mehmood, A.; Kwon, E.E. Recent advancements in supercapacitor technology. Nano Energy 2018, 52, 441–473. [CrossRef]

- Oyedotun, K.O.; Ighalo, J.O.; Amaku, J.F.; Olisah, C.; Adeola, A.O.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Akpomie, K.G.; Conradie, J.; Adegoke, K.A. Advances in Supercapacitor Development: Materials, Processes, and Applications. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 52, 96–129. [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, M.I.A.A.; Fahim, R.A.; Shalan, A.E.; Elkodous, M.A.; Olojede, S.O.; Osman, A.I.; Farrell, C.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Awed, A.S.; Ashour, A.H.; et al. Advanced materials and technologies for supercapacitors used in energy conversion and storage: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 375–439. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Amin, A.A.Y.; Wu, L.; Cao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ameri, T. Perovskite Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Stability, and Optoelectronic Applications. Small Struct. 2021, 2, 2000124. [CrossRef]

- E. T. Bonatto, G. I. Selli, P. T. Martin, and F. T. Bonatto, “Perovskite Nanomaterials: Properties and Applications BT - Environmental Applications of Nanomaterials,” A. Kopp Alves, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 255–267. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhou, T.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, X.; Tu, Y. Perovskite-Based Solar Cells: Materials, Methods, and Future Perspectives. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Sgourou, E.N.; Panayiotatos, Y.; Davazoglou, K.; Solovjov, A.L.; Vovk, R.V.; Chroneos, A. Self-Diffusion in Perovskite and Perovskite Related Oxides: Insights from Modelling. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2286. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ran, R.; Tadé, M.; Wang, W.; Shao, Z. Perovskite materials in energy storage and conversion. Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 11, 338–369. [CrossRef]

- Sunarso, J.; Hashim, S.S.; Zhu, N.; Zhou, W. Perovskite oxides applications in high temperature oxygen separation, solid oxide fuel cell and membrane reactor: A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 61, 57–77. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Alonso, J.A.; Bian, J. Recent Advances in Perovskite-Type Oxides for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Dai, L. Conducting Polymers for Flexible Supercapacitors. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220. [CrossRef]

- P. Kurzweil, “CAPACITORS | Electrochemical Polymer Capacitors,” J. B. T.-E. of E. P. S. Garche, Ed., Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2009, pp. 679–684. [CrossRef]

- Shown, I.; Ganguly, A.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, K.H. Conducting polymer-based flexible supercapacitor. Energy Sci. Eng. 2015, 3, 2–26. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Ruan, Q.; Xue, M.; Chen, L. Emerging perovskite materials for supercapacitors: Structure, synthesis, modification, advanced characterization, theoretical calculation and electrochemical performance. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 89, 41–70. [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Sundriyal, S.; Shrivastav, V.; Mishra, S.; Dubal, D.P.; Kim, K.-H.; Deep, A. Perovskite materials as superior and powerful platforms for energy conversion and storage applications. Nano Energy 2021, 80. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.E.; Hua, Y.; Tezel, F.H. Materials for energy storage: Review of electrode materials and methods of increasing capacitance for supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2018, 20, 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Barber, P.; Balasubramanian, S.; Anguchamy, Y.; Gong, S.; Wibowo, A.; Gao, H.; Ploehn, H.J.; Zur Loye, H.-C. Polymer Composite and Nanocomposite Dielectric Materials for Pulse Power Energy Storage. Materials 2009, 2, 1697–1733. [CrossRef]

- Raza, W.; Ali, F.; Raza, N.; Luo, Y.; Kim, K.-H.; Yang, J.; Kumar, S.; Mehmood, A.; Kwon, E.E. Recent advancements in supercapacitor technology. Nano Energy 2018, 52, 441–473. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, F.; Dorrell, D.G. A review of supercapacitor modeling, estimation, and applications: A control/management perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1868–1878. [CrossRef]

- Moniruddin; Ilyassov, B.; Zhao, X.; Smith, E.; Serikov, T.; Ibrayev, N.; Asmatulu, R.; Nuraje, N. Recent progress on perovskite materials in photovoltaic and water splitting applications. Mater. Today Energy 2018, 7, 246–259. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, M.K.; Antony, A.; Subha, P.P. Energy Harvesting and Storage; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2022; ISBN: 9789811945250.

- Larramendi, N. Ortiz-Vitoriano, I. Bautista, and T. Rojo, “Designing Perovskite Oxides for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, X.; Yue, L.; Liu, Q.; Lu, S.; Asiri, A.M.; Hu, J.; Luo, Y.; Sun, X. Recent advances in perovskite oxides as electrode materials for supercapacitors. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2343–2355. [CrossRef]

- John, B.; Cheruvally, G. Polymeric materials for lithium-ion cells. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2017, 28, 1528–1538. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Jayatissa, A.H. Perovskites-Based Solar Cells: A Review of Recent Progress, Materials and Processing Methods. Materials 2018, 11, 729. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Mishra, S. Moharana, S. K. Satpathy, P. Mallick, and R. N. Mahaling, “Perovskite-type dielectric ceramic- based polymer composites for energy storage applications,” in Perovskite Metal Oxides: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications, Elsevier, 2023, pp. 285–312. [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Suhail, A.; Bag, M. Tuning Conductivity of Lead-Free Cs2AgBiBr6 Double Perovskite Ternary Composite with PEDOT:PSS and Carbon Black for Supercapacitor Application. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 12874–12881. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J. Highly Stable and Luminescent Perovskite–Polymer Composites from a Convenient and Universal Strategy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 4971–4980. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Paul, T.; Maiti, S.; Chattopadhyay, K.K. All-inorganic CsPbBr3 perovskite as potential electrode material for symmetric supercapacitor. Solid State Sci. 2021, 122. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, R.; Li, F.; Xie, H.; He, P.; Sha, Q.; Tang, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhong, H. One-Step Polymeric Melt Encapsulation Method to Prepare CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots/Polymethyl Methacrylate Composite with High Performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010009. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, D.; Guo, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, M.; Xu, T.; Zhu, J.; Fan, B.; Liu, W.; Shao, G.; et al. CsPbBr3 nanocrystals prepared by high energy ball milling in one-step and structural transformation from CsPbBr3 to CsPb2Br5. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 543. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fei, L.; Gao, F.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. Thermal polymerization synthesis of CsPbBr3 perovskite-quantum-dots@copolymer composite: Towards long-term stability and optical phosphor application. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, T.; Perumal, V.; Khor, S.F.; Anthony, L.S.; Gopinath, S.C.; Mohamed, N.M. The recent development of polysaccharides biomaterials and their performance for supercapacitor applications. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 126. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wu, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Chen, M.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, D.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, Y. Interfacial Synthesis of Highly Stable CsPbX3/Oxide Janus Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 140, 406–412. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ding, T.; Daniels, E.S.; Dimonie, V.L.; Klein, A.; El-Aasser, M.S. Synthesis of well-defined, functionalized polymer latex particles through semicontinuous emulsion polymerization processes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 88, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Laysandra, L.; Fan, Y.J.; Adena, C.; Lee, Y.-T.; Au-Duong, A.-N.; Chen, L.-Y.; Chiu, Y.-C. Improving the Lifetime of CsPbBr3 Perovskite in Water Using Self-Healing and Transparent Elastic Polymer Matrix. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 766. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Wu, C.-C.; Wu, C.-L.; Lin, C.-W. CsPbBr3 Perovskite Powder, a Robust and Mass-Producible Single-Source Precursor: Synthesis, Characterization, and Optoelectronic Applications. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 8081–8086. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.A.; Tarasov, A.B. Methylammonium Polyiodides in Perovskite Photovoltaics: From Fundamentals to Applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 418. [CrossRef]

- Stoumpos, C.C.; Malliakas, C.D.; Peters, J.A.; Liu, Z.; Sebastian, M.; Im, J.; Chasapis, T.C.; Wibowo, A.C.; Chung, D.Y.; Freeman, A.J.; et al. Crystal Growth of the Perovskite Semiconductor CsPbBr3: A New Material for High-Energy Radiation Detection. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 2722–2727. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Munawar, T.; Mukhtar, F.; Nadeem, M.S.; Manzoor, S.; Ashiq, M.N.; Iqbal, F. Facile synthesis of polyaniline-supported halide perovskite nanocomposite (KCuCl3/PANI) as potential electrode material for supercapacitor. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 24462–24476. [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; He, L.; Song, S.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, H. In Situ Embedding Synthesis of Highly Stable CsPbBr3/CsPb2Br5@PbBr(OH) Nano/Microspheres through Water Assisted Strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2103275. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, P.; Li, Y.; Xie, R.-J. Improved stability of CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots achieved by suppressing interligand proton transfer and applying a polystyrene coating. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 21441–21450. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jin, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tong, Y.; He, Z.; Liang, X.; Xiang, W. Composition Optimization of Multifunctional CsPb(Br/I)3 Perovskite Nanocrystals Glasses with High Photoluminescence Quantum Yield. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2002075. [CrossRef]

- Galal, A.; Hassan, H.K.; Atta, N.F.; Jacob, T. Energy and cost-efficient nano-Ru-based perovskites/RGO composites for application in high performance supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 538, 578–586. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Lee, C.; Cho, S.; Moon, G.D.; Kim, B.-S.; Chang, H.; Jang, H.D. High capacitance and energy density supercapacitor based on biomass-derived activated carbons with reduced graphene oxide binder. Carbon 2018, 132, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Akhtar, M.S.; Yang, O.-B. Supercapacitors with ultrahigh energy density based on mesoporous carbon nanofibers: Enhanced double-layer electrochemical properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 653, 212–218. [CrossRef]

- Fuhu, L.; Weidong, C.; Zengmin, S.; Yixian, W.; Yunfang, L.; Hui, L. Activation of mesocarbon microbeads with different textures and their application for supercapacitor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Y. Slimani and E. Hannachi, “Ru-based perovskites/RGO composites for applications in high performance supercapacitors.” 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pickup, P.G. Ru oxide supercapacitors with high loadings and high power and energy densities. J. Power Sources 2008, 176, 410–416. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Yu, P.; Ma, Y. High performance supercapacitors based on reduced graphene oxide in aqueous and ionic liquid electrolytes. Carbon 2011, 49, 573–580. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Mengesha, T.T.; Hong, S.-W.; Kim, H.-K.; Hwang, Y.-H. A Comparative Study of the Effects of Different Methods for Preparing RGO/Metal-Oxide Nanocomposite Electrodes on Supercapacitor Performance. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2020, 76, 264–272. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zheng, S.; Xu, Y.; Xue, H.; Pang, H. Ruthenium based materials as electrode materials for supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 333, 505–518. [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Liu, D.; Pan, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Shen, J. Enhanced capacitive behavior of carbon aerogels/reduced graphene oxide composite film for supercapacitors. Solid State Ionics 2013, 247-248, 66–70. [CrossRef]

- Chaitra, K.; Sivaraman, P.; Vinny, R.; Bhatta, U.M.; Nagaraju, N.; Kathyayini, N. High energy density performance of hydrothermally produced hydrous ruthenium oxide/multiwalled carbon nanotubes composite: Design of an asymmetric supercapacitor with excellent cycle life. J. Energy Chem. 2016, 25, 627–635. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; El-Kady, M.F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Shao, Y.; Marsh, K.; Ko, J.M.; Kaner, R.B. Direct preparation and processing of graphene/RuO 2 nanocomposite electrodes for high-performance capacitive energy storage. Nano Energy 2015, 18, 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, D.; Ren, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, G.; Li, F.; Cheng, H. Anchoring Hydrous RuO2 on Graphene Sheets for High-Performance Electrochemical Capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 3595–3602. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wang, J.; Zhu, G.; Kang, L.; Hao, Z.; Lei, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.-H. RuO2/graphene hybrid material for high performance electrochemical capacitor. J. Power Sources 2014, 248, 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Amir, F.Z.; Pham, V.H.; Dickerson, J.H. Facile synthesis of ultra-small ruthenium oxide nanoparticles anchored on reduced graphene oxide nanosheets for high-performance supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 67638–67645. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, K.; Yang, F.; Yan, J.; Zhu, K.; Ye, K.; Wang, G.; Zhou, L.; et al. A flexible and high voltage symmetric supercapacitor based on hybrid configuration of cobalt hexacyanoferrate/reduced graphene oxide hydrogels. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 335, 321–329. [CrossRef]

- S. Singh, “Recent advancements in supercapacitor technology.” 2018. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2211285518305755.

- He, B.; Lu, A.-H.; Cheng, F.; Yu, X.-F.; Yan, D.; Li, W.-C. Fabrication of high-energy hybrid capacitors by using carbon-sulfur composite as promising cathodes. J. Power Sources 2018, 396, 102–108. [CrossRef]

- Siwal, S.S.; Zhang, Q.; Devi, N.; Thakur, V.K. Carbon-Based Polymer Nanocomposite for High-Performance Energy Storage Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 505. [CrossRef]

- Thangappan, R.; Arivanandhan, M.; Kumar, R.D.; Jayavel, R. Facile synthesis of RuO2 nanoparticles anchored on graphene nanosheets for high performance composite electrode for supercapacitor applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2018, 121, 339–349. [CrossRef]

- Jaidev; Jafri, R.I.; Ramaprabhu, S. Hydrothermal Synthesis of RuO2·xH2O/Graphene Hybrid Nanocomposite for Supercapacitor Application. 2011 International Conference on Nanoscience, Technology and Societal Implications (NSTSI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–5.

- Hong, X.; Fu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Dong, W.; Yang, S. Recent Progress on Graphene/Polyaniline Composites for High-performance Supercapacitors. Materials 2019, 12, 1451. [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, A.; Li, L.; Yang, Y. Polyaniline supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2017, 347, 86–107. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, B. Supercapacitors based on nanostructured carbon. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 159–173. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.L.M.; Amitha, F.E.; Jafri, I.; Ramaprabhu, S. Asymmetric Flexible Supercapacitor Stack. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 145–151. [CrossRef]

- Prévost, V.; Petit, A.; Pla, F. Studies on chemical oxidative copolymerization of aniline and o-alkoxysulfonated anilines II. Mechanistic approach and monomer reactivity ratios. Eur. Polym. J. 1999, 35, 1229–1236. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.M.; Le Bris, T.; Graillat, C.; D’aGosto, F.; Lansalot, M. Use of a Poly(ethylene oxide) MacroRAFT Agent as Both a Stabilizer and a Control Agent in Styrene Polymerization in Aqueous Dispersed System. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 946–956. [CrossRef]

- Jeyakumari, J.J.L.; Yelilarasi, A.; Sundaresan, B.; Dhanalakshmi, V.; Anbarasan, R. Chemical synthesis of poly(aniline-co-o/m-toluidine)/V2O5 nano composites and their characterizations. Synth. Met. 2010, 160, 2605–2612. [CrossRef]

- Eisazadeh, H.; Eghtesadi, M. Synthesis of Processable Conducting Polyaniline Nanocomposite Based on Novel Methodology. High Perform. Polym. 2009, 22, 534–549. [CrossRef]

- Joy, R.; Haridas, S. Polyaniline enfolded titanate perovskite: A promising material for supercapacitor applications. Polym. Bull. 2023, 81, 2129–2142. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Pan, Z.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. High-energy-density with polymer nanocomposites containing of SrTiO3 nanofibers for capacitor application. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 109, 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.H.; Li, X.Y.; Li, L. Research Review of Composite Electrode Materials for Super Capacitor. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 851, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T. Polyaniline/graphene nanocomposites towards high-performance supercapacitors: A review. Compos. Commun. 2018, 8, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Shen, Z.X. Polyaniline (PANi) based electrode materials for energy storage and conversion. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2016, 1, 225–255. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, G.Z. Supercapatteries as High-Performance Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2020, 3, 271–285. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Peng, C.; Peng, F.; Yu, H. Preparation and the Electrochemical Performance of MnO2/PANI@CNT Composite for Supercapacitors. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 709–714. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, L.; Vellacheri, R.; Lei, Y. Recent Advances in Designing and Fabricating Self-Supported Nanoelectrodes for Supercapacitors. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700188–1700188. [CrossRef]

- Bonatto, G. Selli, P. Martin, and F. Bonatto, “Perovskite Nanomaterials: Properties and Applications.” 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Cui, X.; Zu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Lian, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Ultra High Electrical Performance of Nano Nickel Oxide and Polyaniline Composite Materials. Polymers 2017, 9, 288. [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, N.K.; Venkataratnam, K.K.; Murty, P.N.; Kumar, K.V. Preparation and characterization of PAN–KI complexed gel polymer electrolytes for solid-state battery applications. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2016, 39, 1047–1055. [CrossRef]

- Naoi, K.; Naoi, W.; Aoyagi, S.; Miyamoto, J.-I.; Kamino, T. New Generation “Nanohybrid Supercapacitor”. Accounts Chem. Res. 2012, 46, 1075–1083. [CrossRef]

- W. L. F. Armarego and C. L. L. Chai, “Chapter 5 - Purification of Inorganic and Metal Organic Chemicals: (Including Organic compounds of B, Bi, P, Se, Si, and ammonium and metal salts of organic acids),” W. L. F. Armarego and C. L. L. B. T.-P. of L. C. (Fifth E. Chai, Eds., Burlington: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003, pp. 389–499. [CrossRef]

- Güz, S.; Buldu-Akturk, M.; Göçmez, H.; Erdem, E. All-in-One Electric Double Layer Supercapacitors Based on CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Electrodes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 47306–47316. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gong, L. Research Progress on Applications of Polyaniline (PANI) for Electrochemical Energy Storage and Conversion. Materials 2020, 13, 548. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, M.; Yin, J.; Abou-Hamad, E.; Schwingenschlögl, U.; Costa, P.M.F.J.; Alshareef, H.N. A Cyclized Polyacrylonitrile Anode for Alkali Metal Ion Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 60, 1355–1363. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, N.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kong, L.; Kang, L.; Ran, F. High rate capability and long cycle-life of nickel oxide membrane electrode incorporated with nickel and coated with carbon layer via in-situ supporting of engineering plastic for energy storage application. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 710, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiang, K.; Tranca, D.; Ke, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Tong, G.; Kymakis, E.; Zhuang, X. Perovskite oxide and polyazulene–based heterostructure for high–performance supercapacitors. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 51198. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Du, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhan, J.; Wang, H. Ultra-long lifespan asymmetrical hybrid supercapacitor device based on hierarchical NiCoP@C@LDHs electrode. Electrochimica Acta 2020, 334. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, B.; Zeng, G.; Nogita, K.; Ye, D.; Wang, L. Electrochemical and Structural Study of Layered P2-Type Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2 as Cathode Material for Sodium-Ion Battery. Chem. – Asian J. 2015, 10, 661–666. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Wen, T.-C.; Teng, H. Polyaniline-deposited porous carbon electrode for supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta 2003, 48, 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xue, X.; Li, C.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Nan, H.; Hu, X.; Tian, H. Rational design of La0.85Sr0.15MnO3@NiCo2O4 Core–Shell architecture supported on Ni foam for high performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2018, 402, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.I.; Sunarso, J.; Wong, B.T.; Lin, H.; Yu, A.; Jia, B. Towards enhanced energy density of graphene-based supercapacitors: Current status, approaches, and future directions. J. Power Sources 2018, 396, 182–206. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Ju, B.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Wu, H. Supercapacitive behaviors of activated mesocarbon microbeads coated with polyaniline. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14365–14372. [CrossRef]

- Popoola, I.K.; Gondal, M.A.; Popoola, A.; Oloore, L.E.; Younas, M. Inorganic perovskite photo-assisted supercapacitor for single device energy harvesting and storage applications. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Hong, W.; Yang, L.; Tian, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zou, G.; Hou, H.; Ji, X. Bi-Based Electrode Materials for Alkali Metal-Ion Batteries. Small 2020, 16, e2004022. [CrossRef]

- Popoola, I.K.; Gondal, M.A.; Popoola, A.; Oloore, L.E. Bismuth-based organometallic-halide perovskite photo-supercapacitor utilizing novel polymer gel electrolyte for hybrid energy harvesting and storage applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Ma, L.; Tie, Z.; Liu, J.; Jin, Z. An all-inorganic perovskite solar capacitor for efficient and stable spontaneous photocharging. Nano Energy 2018, 52, 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Berestok, T.; Diestel, C.; Ortlieb, N.; Glunz, S.W.; Fischer, A. A Monolithic Silicon-Mesoporous Carbon Photosupercapacitor with High Overall Photoconversion Efficiency. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, H. Energy storage via polyvinylidene fluoride dielectric on the counterelectrode of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 2013, 248, 434–438. [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Yoo, K.; Kim, J. Semi-Polycrystalline Polyaniline-Activated Carbon Composite for Supercapacitor Application. Molecules 2023, 28, 1520. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Yao, S.; Gao, F.; Duan, L.; Niu, M.; Liu, J. Reduced graphene oxide/Mn3O4 nanohybrid for high-rate pseduocapacitive electrodes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 511, 434–439. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Si, P. Electrochemical Characterization of Nanostructured LiMn2O4 Composite in Lithium-Ion Hybrid Supercapacitors. ChemElectroChem 2020, 8, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lang, J.; Gao, R. Highly conductive KNiF3@carbon nanotubes composite materials with cross-linked structure for high performance supercapacitor. J. Power Sources 2020, 474. [CrossRef]

- Ju, K.; Miao, Y.; Li, Q.; Yan, Y.; Gao, Y. Laser Direct Writing of MnO2/Carbonized Carboxymethylcellulose-Based Composite as High-Performance Electrodes for Supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 7690–7698. [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, M.I.A.A.; Fahim, R.A.; Shalan, A.E.; Elkodous, M.A.; Olojede, S.O.; Osman, A.I.; Farrell, C.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Awed, A.S.; Ashour, A.H.; et al. Advanced materials and technologies for supercapacitors used in energy conversion and storage: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 375–439. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hao, Z.; Zeng, F.; Xu, J.; Nan, H.; Meng, Z.; Yang, J.; Shi, W.; Zeng, Y.; Hu, X.; et al. Coaxial cable-like dual conductive channel strategy in polypyrrole coated perovskite lanthanum manganite for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 610, 601–609. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, L.-B.; Cai, J.-J.; Luo, Y.-C.; Kang, L. Nano-composite of polypyrrole/modified mesoporous carbon for electrochemical capacitor application. Electrochimica Acta 2010, 55, 8067–8073. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, H.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, A.; Xia, T.; Dong, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. Progress of electrochemical capacitor electrode materials: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 4889–4899. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Du, P.; Wei, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, P. Flexible and robust reduced graphene oxide/carbon nanoparticles/polyaniline (RGO/CNs/PANI) composite films: Excellent candidates as free-standing electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 259, 161–169. [CrossRef]

- Xi, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Direct Synthesis of MnO2 Nanorods on Carbon Cloth as Flexible Supercapacitor Electrode. J. Nanomater. 2017, 2017, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Goikolea, E.; Balducci, A.; Naoi, K.; Taberna, P.; Salanne, M.; Yushin, G.; Simon, P. Materials for supercapacitors: When Li-ion battery power is not enough. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 419–436. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Chen, H. The effect of carbon black in carbon counter electrode for CH3NH3PbI3/TiO2 heterojunction solar cells. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 30192–30196. [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Skorenko, K.H.; Faucett, A.C.; Boyer, S.M.; Liu, J.; Mativetsky, J.M.; Bernier, W.E.; Jones, W.E. Vapor-phase polymerization of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) on commercial carbon coated aluminum foil as enhanced electrodes for supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2015, 297, 195–201. [CrossRef]

- Marcomini, A.L.; Dias, J.A.; Morelli, M.R.; Bretas, R.E.S. Potential supercapacitors made of polymer/perovskite composites. PROCEEDINGS OF PPS-33 : The 33rd International Conference of the Polymer Processing Society – Conference Papers. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MexicoDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 110005.

- Gao, Y. Graphene and Polymer Composites for Supercapacitor Applications: A Review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cai, G.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, X. Oxidative chemical polymerization of 3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene and its applications in antistatic coatings. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 124, 109–115. [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Yu, S.; Tay, F.E.H. Preparation of perovskite Pb(Zn1∕3Nb2∕3)O3-based thin films from polymer-modified solution precursors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 052904. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du Pasquier, A.; Li, D.; Atanassova, P.; Sawrey, S.; Oljaca, M. Electrochemical double layer capacitors containing carbon black additives for improved capacitance and cycle life. Carbon 2018, 133, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Hu, X.; Yi, C.; Liu, H.C.; Liu, P.; Zhang, H.; Gong, X. Self-Powered Electronics by Integration of Flexible Solid-State Graphene-Based Supercapacitors with High Performance Perovskite Hybrid Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 2420–2427. [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, H.; Zhao, G.; Ma, G.; Lei, Z. Hybrid symmetric supercapacitor assembled by renewable corn silks based porous carbon and redox-active electrolytes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 218, 229–238. [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Wilson, P.; Lekakou, C. Effect of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) in carbon-based composite electrodes for electrochemical supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 7823–7827. [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Fu, Q.; Qiu, C.; Bie, X.; Du, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, H.; Chen, G.; Wei, Y. Carbon black and vapor grown carbon fibers binary conductive additive for the Li1.18Co0.15Ni0.15Mn0.52O2 electrodes for Li-ion batteries. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 156, 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Panić, V.; Dekanski, A.; Stevanović, R. Sol–gel processed thin-layer ruthenium oxide/carbon black supercapacitors: A revelation of the energy storage issues. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 3969–3976. [CrossRef]

- Forouzandeh, P.; Kumaravel, V.; Pillai, S.C. Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors: A Review of Recent Advances. Catalysts 2020, 10, 969. [CrossRef]

- Seok, S.I.; Guo, T.-F. Halide perovskite materials and devices. MRS Bull. 2020, 45, 427–430. [CrossRef]

- H.-J. Choi, S.-M. Jung, J.-M. Seo, D. W. Chang, L. Dai,.

- Choi, H.-J.; Jung, S.-M.; Seo, J.-M.; Chang, D.W.; Dai, L.; Baek, J.-B. Graphene for energy conversion and storage in fuel cells and supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 534–551. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).