Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Microbiomes and Algae in Forest Ecosystems

3. Functional Mechanisms Enhancing Seed Germination

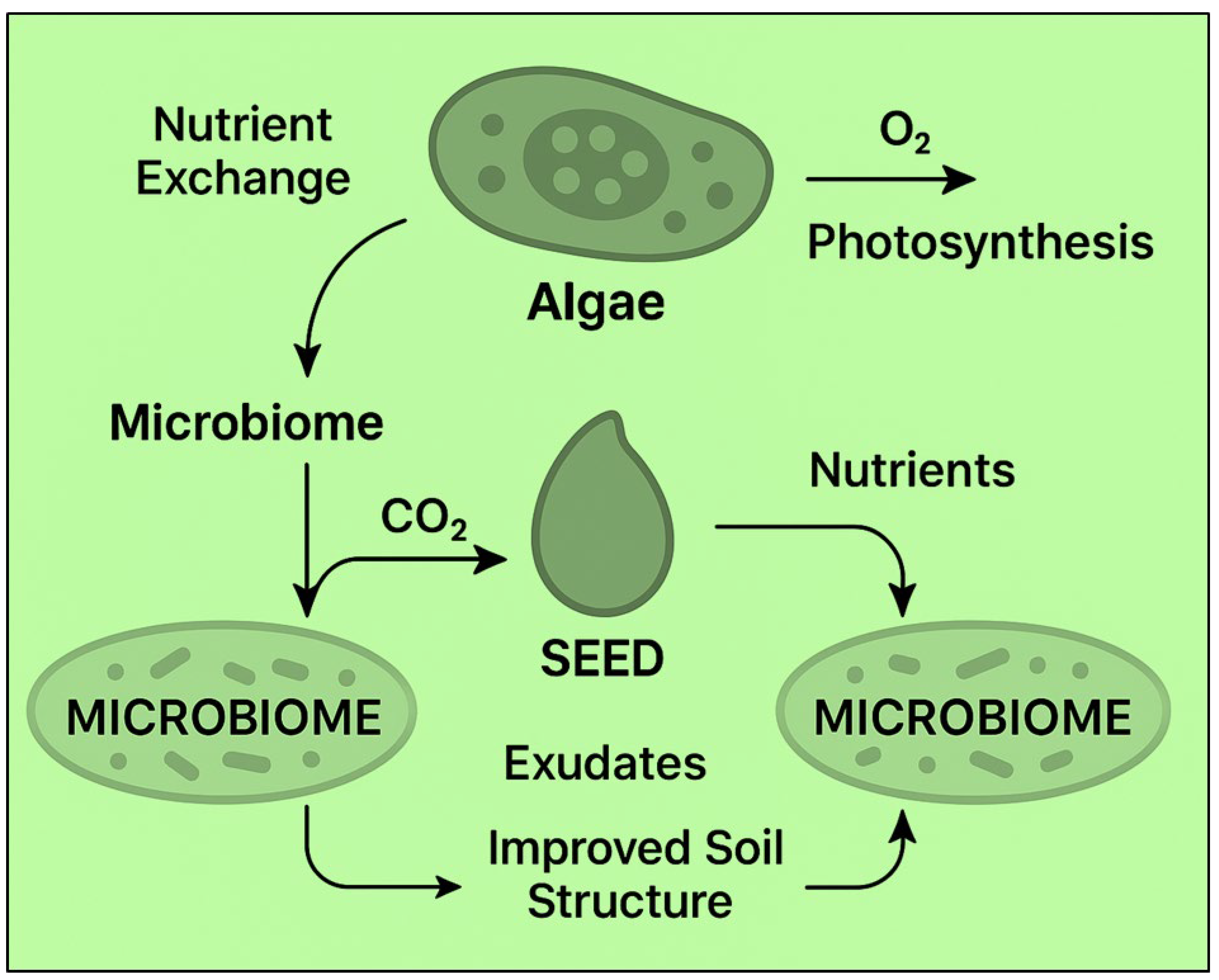

4. Microbiome–Algae Interactions in the Soil–Seed Interface

4.1. Synergistic Effects on Nutrient Cycling and Bioactive Compound Production

4.2. Competitive and Facilitative Relationships

4.3. Impact on Seed Microenvironment and Germination Rates

5. Forest Seed Germination: Processes and Ecological Significance

5.1. Physiological Stages of Seed Germination in Forest Species

5.2. Differences Between Pioneer and Climax Forest Seeds

5.3. Case Studies of Threatened and Endangered Forest Seeds

6. Biotechnological Applications for Enhancing Forest Seed Germination

7. Challenges and Limitations

8. Future Research Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguirre-Gutiérrez, J.; Díaz, S.; Rifai, S.W.; Corral-Rivas, J.J.; Nava-Miranda, M.G.; González-M, R.; Hurtado-M, A.B.; Revilla, N.S.; Vilanova, E.; Almeida, E.; de Oliveira, E.A. Tropical forests in the Americas are changing too slowly to track climate change. Science 2025, 387, eadl5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manojkumar, S.; Maurya, L.L.; Kumar, S.; George, E. Impact of Forest Degradation on Forest Regeneration. In Forest Degradation and Management. 2025 (pp. 195–206). Springer, Cham.

- Atakpama, W.; Egbelou, H.; Bali, B.E.; Ahouandjinou, E.B.; Dibegdina, M.; Batawila, K. Challenges for the conservation and restoration of the forest ecosystems of the Oti-Kéran-Mandouri Biosphere Reserve in Togo. Ann. Rech. For. Alge rie. 2025, 15, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Hu, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J.; Maeda, E.E.; Ju, W.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; Su, Y. Enhancing ecosystem productivity and stability with increasing canopy structural complexity in global forests. Science Advances. 2024, 10, eadl1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussier, N.M.; Crafford, R.E.; Reid, J.L.; Kwit, C. Seeding success: Integrating seed dispersal networks in tropical forest restoration. Biotropica. 2025, 57, e13347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargah, A.S.; Sharma, D.; Kumar, R.; Nag, R.; Pradhan, R. Enhancing germination of forest tree seeds in Chhattisgarh through PGR-based treatments: A review. Journal of Advances in Biology & Biotechnology. 2025, 28, 851–863. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani, G.Q.; Duarte, M.L.; Almeida, L.S.; Martins Filho, S. Non-parametric survival analysis in seed germination of forest species. Journal of Seed Science. 2024, 46, e202446036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhri, M.; Setiawan, N.N.; Dewi, S.P.; Sulistyawati, E. Seed germination variability and its association with functional traits in submontane tropical forest species of Indonesia: recommendations for direct seeding. Forest Science and Technology. 2025, 21, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Lu, L.; Condrich, A.; Muni, G.A.; Scranton, S.; Xu, S.; Xia, Y.; Huang, S. Innovative Approaches for Engineering the Seed Microbiome to Enhance Crop Performance. Seeds. 2025, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Singh, P.; Middleton, J.; Merritt, D.; Jenkins, S.; Nichols, P. Impact of seed maturation on the morphology, nutrition, microbiome composition and germinability of subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum) seeds. Grass and Forage Science. 2025, 80, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Priya, P.; Sivamurugan, V. Microbial Interactions in Soil Algae. In Soil Algae: Morphology, Ecology and Biotechnological Applications. 2025 (pp. 1–35). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Shukla, S.; Upadhyay, D.; Mishra, A.; Jindal, T.; Shukla, K. The Impact on Soil Ecology of the Algal Community. In Soil Algae: Morphology, Ecology and Biotechnological Applications. 2025 (pp. 193–219). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Onet, A.; Grenni, P.; Onet, C.; Stoian, V.; Crisan, V. Forest soil microbiomes: a review of key research from 2003 to 2023. Forests. 2025, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.I.; Gundersen, P.; Bezemer, T.M.; Barsotti, D.; D’Imperio, L.; Georgopoulos, K.; Justesen, M.J.; Rheault, K.; Rosas, Y.M.; Schmidt, I.K.; Tedersoo, L. Soil Microbiome Inoculation for Resilient and Multifunctional New Forests in Post-Agricultural Landscapes. Global Change Biology. 2025, 31, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; McClure, R.; Egbert, R.G. Soil microbiome engineering for sustainability in a changing environment. Nature Biotechnology. 2023, 41, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, E.A.; Suleymanov, A.R.; Nikitin, D.A.; Semenov, M.V.; Abakumov, E.V. Machine learning-based mapping of Acidobacteriota and Planctomycetota using 16 S rRNA gene metabarcoding data across soils in Russia. Scientific Reports. 2025, 15, 23763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczki, K.; Tóth, E.G.; Szili-Kovács, T.; Megyes, M.; Korponai, K.; Lados, B.B.; Illés, G.; Benke, A.; Márialigeti, K. Soil Parameters and Forest Structure Commonly Form the Microbiome Composition and Activity of Topsoil Layers in Planted Forests. Microorganisms. 2024, 12, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Wu, S.; Pan, H.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. Effect of forest fires on the alpha and beta diversity of soil bacteria in taiga forests: proliferation of rare species as successional pioneers. Forests. 2024, 15, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakitin, A.L.; Kulichevskaya, I.S.; Beletsky, A.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; Dedysh, S.N.; Ravin, N.V. Verrucomicrobia of the family Chthoniobacteraceae participate in xylan degradation in boreal peat soils. Microorganisms. 2024, 12, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Kavana, D.J.; Zhang, G.; He, S.; Yu, B. The Characteristics of Soil Microbial Community Structure, Soil Microbial Respiration and their Influencing Factors of Three Vegetation Types in Alpine Wetland Ecosystem. Wetlands. 2024, 44, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Nowak, V.; Zhi, S.; Jin, M.; Liu, L.; He, S. Genome Mining Analysis Uncovers the Previously Unknown Biosynthetic Capacity for Secondary Metabolites in Verrucomicrobia. Marine Biotechnology. 2024, 26, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebai, H.; Sholkamy, E.N.; Abdelhamid, M.A.; Prakasam Thanka, P.; Aly Hassan, A.; Pack, S.P.; Ki, M.R.; Boudemagh, A. Soil actinobacteria exhibit metabolic capabilities for degrading the toxic and persistent herbicide Metribuzin. Toxics. 2024, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.; Joshi, P.; Pal, M.; Parkash, V. Actinobacteria as Proficient Biocontrol Agents for Combating Fungal Diseases in Forest Plant Species. Journal of Basic Microbiology. 2025, 2, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Mahmud, U.; Shoumik, B.A.; Khan, M.Z. Although invisible, fungi are recognized as the engines of a microbial powerhouse that drives soil ecosystem services. Archives of Microbiology. 2025, 207, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Sun, H. Soil fungal community and potential function in different forest ecosystems. Diversity. 2022, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Ma, D.; Li, D.; Han, X.; Cai, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J. Saprotrophic fungal communities in arable soils are strongly associated with soil fertility and stoichiometry. Applied Soil Ecology. 2021, 159, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A.F.; Nakabonge, G.; Ssekandi, J.; Founoune-Mboup, H.; Apori, S.O.; Ndiaye, A.; Badji, A.; Ngom, K. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on soil fertility: contribution in the improvement of physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil. Frontiers in fungal biology. 2022, 3, 723892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Poudyal, S.; Kaundal, A. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in maintaining sustainable agroecosystems. Applied Microbiology. 2025, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediriweera, A.N.; Lu, W.; Perez Moreno, J.; Kalamulla, R.; Mayadunna, N.; Pelewatta, A.; Dissanayake, G.; Maduwanthi, I.; Wijesooriya, M.; Dai, D.Q.; Yapa, N. Ectomycorrhizal fungal symbiosis on plant nutrient acquisition in tropical ecosystems. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 2025, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballaoui, M.; El Gabardi, S.; Chliyeh, M.; Selmaoui, K.; Saidi, N.; Alaoui, M.A.; Mouden, N.; Benkirane, A.R.; Ouazzani Touhami, A.; Douira, A. Diversity of Endomycorrhizal Fungi in the Rhizosphere of Fig Trees in the Region of Ifrane (Middle Atlas Region of Northern Morocco). In Advanced Systems for Environmental Monitoring, IoT and the application of Artificial Intelligence. 2024 (pp. 109–122). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Song, B.; Fang, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, N.; Pena, R.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Adams, J.M.; Razavi, B.S. The development of biological soil crust along the time series is mediated by archaeal communities. Geoderma. 2024, 449, 117022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, M.; Huang, W.; Zou, X.; He, Z.; Shu, L. Soil protists are more resilient to the combined effect of microplastics and heavy metals than bacterial communities. Science of the total environment. 2024, 906, 167645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorentz, J.F.; Calijuri, M.L.; Rad, C.; Cecon, P.R.; Assemany, P.P.; Martinez, J.M.; Kholssi, R. Microalgae biomass as a conditioner and regulator of soil quality and fertility. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2024, 196, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeheyo, H.A.; Ealias, A.M.; George, G.; Jagannathan, U. Bioremediation potential of microalgae for sustainable soil treatment in India: a comprehensive review on heavy metal and pesticide contaminant removal. Journal of Environmental Management. 2024, 363, 121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, X.; Laipan, M.; Wei, T.; Guo, J. Soil health improvement by inoculation of indigenous microalgae in saline soil. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2024, 46, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Saxena, R.C. An introduction to microalgae: diversity and significance. In Handbook of marine microalgae. 2015 (pp. 11–24). Academic Press.

- Alvarez, A.L.; Weyers, S.L.; Goemann, H.M.; Peyton, B.M.; Gardner, R.D. Microalgae, soil and plants: A critical review of microalgae as renewable resources for agriculture. Algal Research. 2021, 54, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abinandan, S.; Subashchandrabose, S.R.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Soil microalgae and cyanobacteria: the biotechnological potential in the maintenance of soil fertility and health. Critical reviews in biotechnology. 2019, 39, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerna, D.; Clara, D.; Antonielli, L.; Mitter, B.; Roach, T. Seed imbibition and metabolism contribute differentially to initial assembly of the soybean holobiont. Phytobiomes journal. 2023, 8, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zi, H.; Sonne, C.; Li, X. Microbiome sustains forest ecosystem functions across hierarchical scales. Eco-Environment & Health. 2023, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Chen, W.; Luo, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shu, D.; Wei, G. Seed microbiomes promote Astragalus mongholicus seed germination through pathogen suppression and cellulose degradation. Microbiome. 2025, 13, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq, I.; Reshi, Z.A.; Bashir, I. Diversity and Plant Growth-Promoting Activities of Culturable Seed Endophytes in Abies pindrow (Royle ex D. Don) Royle: Their Role in Seed Germination and Seedling Growth. Current Microbiology. 2025, 82, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, D.E.; Sevanto, S.; Peterson, S.; Ryan, M.; Dunbar, J. Effects of soil microbes on functional traits of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) seedling families from contrasting climates. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2020, 10, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, R.M.; Martínez, M.H.; Díaz-Santiago, E.; Pugnaire, F.I. Microbial controls on seed germination. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2024, 199, 109576. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, D.J.; Travers, S.K.; Val, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.T.; Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Experimental evidence of strong relationships between soil microbial communities and plant germination. Journal of Ecology. 2021, 109, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, R.; Singh, R.L. Microbes and environment. In Principles and applications of environmental biotechnology for a sustainable future. 2016 (pp. 43–84). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Mahala, D.M.; Maheshwari, H.S.; Yadav, R.K.; Prabina, B.J.; Bharti, A.; Reddy, K.K.; Kumawat, C.; Ramesh, A. Microbial transformation of nutrients in soil: an overview. Rhizosphere microbes: Soil and plant functions. 2021; 175-211.

- Singh, B.K.; Hu, H.W.; Macdonald, C.A.; Xiong, C. Microbiome-facilitated plant nutrient acquisition. Cell Host & Microbe. 2025, 33, 869–881. [Google Scholar]

- Vincze, É.B.; Becze, A.; Laslo, É.; Mara, G. Beneficial soil microbiomes and their potential role in plant growth and soil fertility. Agriculture. 2024, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lladó, S.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Baldrian, P. Drivers of microbial community structure in forest soils. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2018, 102, 4331–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Turki, A.; Murali, M.; Omar, A.F.; Rehan, M.; Sayyed, R.Z. Recent advances in PGPR-mediated resilience toward interactive effects of drought and salt stress in plants. Frontiers in microbiology. 2023, 14, 1214845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholostiakov, V.; Burns, B.; Ridgway, H.; Padamsee, M. Variation in seed-borne microbial communities of Metrosideros excelsa Sol. ex Gaertn. with consequences for germination success. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 2025, 63, 1981–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.W.; Li, S.Y.; Zhu, H.; Liu, G.X. Phyllosphere eukaryotic microalgal communities in rainforests: Drivers and diversity. Plant Diversity. 2023, 45, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, P.; Flores-Uribe, J.; Wippel, K.; Zhang, P.; Guan, R.; Melkonian, B.; Melkonian, M.; Garrido-Oter, R. Shared features and reciprocal complementation of the Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis microbiota. Nature Communications. 2022, 13, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobwede, E.; Leake, J.R.; Pandhal, J. Circular economy fertilization: Testing micro and macro algal species as soil improvers and nutrient sources for crop production in greenhouse and field conditions. Geoderma. 2019, 334, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Ryu, C.M. Algae as new kids in the beneficial plant microbiome. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021, 12, 599742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Cortés, G.; Bonneau, S.; Bouchez, O.; Genthon, C.; Briand, M.; Jacques, M.A.; Barret, M. Functional microbial features driving community assembly during seed germination and emergence. Frontiers in plant science. 2018, 9, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Xie, X.; Chen, M.; Qiao, F.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, X.; Liu, F. Co-Inoculation Between Bacteria and Algae from Biological Soil Crusts and Their Effects on the Growth of Poa annua and Sandy Soils Quality. Microorganisms. 2025, 13, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Miao, T.; Hou, H.; Chen, G. The effects of microbial composite fertilizer CAMP on soil improvement and growth of Chinese cabbage. North Hortic. 2018, 12, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Treves, H.; Küken, A.; Arrivault, S.; Ishihara, H.; Hoppe, I.; Erban, A.; Höhne, M.; Moraes, T.A.; Kopka, J.; Szymanski, J.; Nikoloski, Z. Carbon flux through photosynthesis and central carbon metabolism show distinct patterns between algae, C3 and C4 plants. Nature plants. 2022, 8, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dong, H.; Cao, X.; Wang, W.; Li, C. Enhancing photosynthetic CO2 fixation by assembling metal-organic frameworks on Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Nature Communications. 2023, 14, 5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutum, L.; Janda, T.; Darkó, É.; Szalai, G.; Hamow, K.Á.; Molnár, Z. Outcome of microalgae biomass application on seed germination and hormonal activity in winter wheat leaves. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbing, M.E.; Fuqua, C.; Parsek, M.R.; Peterson, S.B. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nature reviews microbiology. 2010, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.G.; Kong, C.C.; Li, S.M.; Wang, X.J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.C.; Qin, S.; Cui, H.L. Symbiotic microalgae and microbes: a new frontier in saline agriculture. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2025, 16, 1540274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirri, E.; Pohnert, G. Algae− bacteria interactions that balance the planktonic microbiome. New Phytologist. 2019, 223, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofintila, O.E.; Noel, Z.A. Soybean and cotton spermosphere soil microbiome shows dominance of soilborne copiotrophs. Microbiology Spectrum. 2023, 11, e00377–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L.M.; De-Bashan, L.E. The potential of microalgae–bacteria consortia to restore degraded soils. Biology. 2023, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Goede, S.P.; Hannula, S.E.; Jansen, B.; Morriën, E. Fungal-mediated soil aggregation as a mechanism for carbon stabilization. The ISME Journal. 2025, 19, wraf074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden E, Ermiş S, Yildirim E, Demir İ. Perspective Chapter: Insights into Seed Germination–Physiological and Environmental Mechanisms. 2025.

- Fernández-Pascual, E.; Carta, A.; Mondoni, A.; Cavieres, L.A.; Rosbakh, S.; Venn, S.; Satyanti, A.; Guja, L.; Briceño, V.F.; Vandelook, F.; Mattana, E. The seed germination spectrum of alpine plants: a global meta-analysis. New phytologist. 2021, 229, 3573–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, B.B.; Pausas, J.G. Seed dormancy revisited: Dormancy-release pathways and environmental interactions. Functional Ecology. 2023, 37, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Castaño, G.; Calleja-Cabrera, J.; Pernas, M.; Gómez, L.; Oñate-Sánchez, L. An updated overview on the regulation of seed germination. Plants. 2020, 9, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manohan, B.; Shannon, D.P.; Tiansawat, P.; Chairuangsri, S.; Jainuan, J.; Elliott, S. Use of functional traits to distinguish successional guilds of tree species for restoring forest ecosystems. Forests. 2023, 14, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebel, K.; Huth, F.; Wagner, S. Soil seed banks of pioneer tree species in European temperate forests: a review. iForest-Biogeosciences and Forestry. 2018, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.S.; De Andrade, L.G.; De Andrade, A.C. Germination of small tropical seeds has distinct light quality and temperature requirements, depending on microhabitat. Plant Biology. 2021, 23, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, T.; Andrus, R.; Aravena, M.C.; Ascoli, D.; Bergeron, Y.; Berretti, R.; Berveiller, D.; Bogdziewicz, M.; Boivin, T.; Bonal, R.; Bragg, D.C. Limits to reproduction and seed size-number trade-offs that shape forest dominance and future recovery. Nature communications. 2022, 13, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iralu, V.; Barbhuyan, H.S.; Upadhaya, K. Ecology of seed germination in threatened trees: a review. Energy, Ecology and Environment. 2019, 4, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley-Lopez, J.M.; Wawrzyniak, M.K.; Chacon-Madrigal, E.; Chmielarz, P. Seed traits and tropical arboreal species conservation: a case study of a highly diverse tropical humid forest region in Southern Costa Rica. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2023, 32, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, R.; Liang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Seed germination ecology of endangered plant Horsfieldia hainanensis Merr. In China. BMC Plant Biology. 2024, 24, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ko, C.H.; Kwon, H.C.; Rhie, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y. Effect of Temperature and Covering Structures in Seed Dormancy and Germination Traits of Manchurian Striped Maple (Acer tegmentosum Maxim.) Native to Northeast Asia. Plants. 2025, 14, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linan, A.G.; Gereau, R.E.; Sucher, R.; Mashimba, F.H.; Bassuner, B.; Wyatt, A.; Edwards, C.E. Capturing and managing genetic diversity in ex situ collections of threatened tropical trees: A case study in Karomia gigas. Applications in Plant Sciences. 2024, 12, e11589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckman, E.; Meyer, A.; Pivorunas, D.; Hoban, S.; Westwood, M. Conservation Gap Analysis of Native. 2021.

- Cuena Lombraña, A.; Dessì, L.; Podda, L.; Fois, M.; Luna, B.; Porceddu, M.; Bacchetta, G. The effect of heat shock on seed dormancy release and germination in two rare and Endangered Astragalus L. species (Fabaceae). Plants. 2024, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, B.D.; Clarke, S.W.; Zimmer, H.C.; Liew, E.C.; Phelan, M.T.; Offord, C.A.; Menke, L.K.; Crust, D.W.; Bragg, J.G.; McPherson, H. Ecology and conservation of a living fossil: Australias Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis). 2021.

- Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Ling, Y.; Liao, N.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, F. Effects of Seed Biological Characteristics and Environmental Factors on Seed Germination of the Critically Endangered Species Hopea chinensis (Merr.) Hand.-Mazz. in China. Forests. 2023, 14, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klupczyńska, E.A.; Pawłowski, T.A. Regulation of seed dormancy and germination mechanisms in a changing environment. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021, 22, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putri, K.P.; Yuniarti, N.; Aminah, A.; Suita, E.; Sudrajat, D.J.; Syamsuwida, D. Seed handling of specific forest tree species: Recalcitrant and intermediate seed. InIOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2020; (Vol. 522, No. 1, p. 012015). IOP Publishing.

- Smith, P.; Pence, V. The role of botanic gardens in ex situ conservation. Plant conservation science and practice: the role of botanic gardens. 2017; 102-33.

- Yang, P.; Lu, L.; Condrich, A.; Muni, G.A.; Scranton, S.; Xu, S.; Xia, Y.; Huang, S. Innovative Approaches for Engineering the Seed Microbiome to Enhance Crop Performance. Seeds. 2025, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, W.; Luo, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shu, D.; Wei, G. Seed microbiomes promote Astragalus mongholicus seed germination through pathogen suppression and cellulose degradation. Microbiome. 2025, 13, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentz, J.F.; Calijuri, M.L.; Rad, C.; Cecon, P.R.; Assemany, P.P.; Martinez, J.M.; Kholssi, R. Microalgae biomass as a conditioner and regulator of soil quality and fertility. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2024, 196, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, R.; Oon, Y.L.; Oon, Y.S.; Bi, Y.; Mi, W.; Song, G.; Gao, Y. Diverse interactions between bacteria and microalgae: A review for enhancing harmful algal bloom mitigation and biomass processing efficiency. Heliyon. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, D.J.; Travers, S.K.; Val, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.T.; Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Experimental evidence of strong relationships between soil microbial communities and plant germination. Journal of Ecology. 2021, 109, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, A.; Pandhal, J. Engineering the phycosphere: fundamental concepts and tools for the bottom-up design of microalgal-bacterial consortia. Applied Phycology. 2025, 6, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koneru, H.; Bamba, S.; Bell, A.; Estrada-Graf, A.A.; Johnson, Z.I. Integrating microbial communities into algal biotechnology: a pathway to enhanced commercialization. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2025, 16, 1555579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, F.; Wang, F.; Le, L.; Pu, L. Synthetic biology and artificial intelligence in crop improvement. Plant Communications. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozaeva, E.; Eida, A.A.; Gunady, E.F.; Dangl, J.L.; Conway, J.M.; Brophy, J.A. Roots of synthetic ecology: microbes that foster plant resilience in the changing climate. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2024, 88, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiodor, A.; Ajijah, N.; Dziewit, L.; Pranaw, K. Biopriming of seed with plant growth-promoting bacteria for improved germination and seedling growth. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2023, 14, 1142966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddle, S.D.; Hodgson, R.J.; Borrett, R.J.; Brachmann, S.; Davies, T.C.; Erickson, T.E.; Liddicoat, C.; Muñoz-Rojas, M.; Robinson, J.M.; Watson, C.D.; Krauss, S.L.; Breed, M.F. Practical applications of soil microbiota to improve ecosystem restoration: current knowledge and future directions. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2025, 100, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Beyer, H.L.; Fagan, M.E.; Chazdon, R.; Schmoeller, M.; Sprenkle-Hyppolite, S.; Griscom, B.W.; Watson, J.E.M.; Tedesco, A.M.; Gonzalez-Roglich, M.; et al. Global potential for natural regeneration in deforested tropical regions. Nature. 2024, 636, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemla, Y.; Sweeney, C.J.; Wozniak, C.A.; Voigt, C.A. Design and regulation of engineered bacteria for environmental release. Nature Microbiology. 2025, 10, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiper, F.; Atanassova, A. International synthetic biology policy developments and implications for global biodiversity goals. Frontiers in Synthetic Biology. 2025, 3, 1585337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microbial/Algal Group | Example Species | Main Functions | Impact on Germination/Seedlings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidobacteriota Bacteria [13,16] |

Acidobacterium capsulatum Acidipila rosea Edaphobacter modestus Terriglobus roseus |

Degradation of polymers (cellulose, lignin, chitin), N–Fe–S cycles, tolerance to acidic soils | Improve soil fertility → indirect stimulation of germination |

| Proteobacteria Bacteria (PGPB) [17,18] |

Rhizobium Azospirillum brasilense Pseudomonas fluorescens Methylobacterium Bradyrhizobium Burkholderia |

Nitrogen fixation, phytohormone production (IAA, cytokinins, gibberellins), antibiosis, biofilms | Accelerated germination, enhanced early growth, biocontrol |

| Verrucomicrobia Bacteria [19,20,21] |

Opitutus terrae Candidatus Udaeobacter copiosus Luteolibacter pohnpeiensis |

Aerobic metabolism, organic matter transformation, production of organic acids & nutrients | Increased fertility, improved mineral nutrition of seeds |

| Actinobacteria Bacteria [22,23] |

Streptomyces Micromonospora Nocardia Frankia spp. |

Production of enzymes (cellulases, ligninases, phosphatases), natural antibiotics, nitrogen-fixing symbioses | Favor germination by improving nutrition and pathogen protection |

| Saprophytic Fungi [25,26] |

Aspergillus niger Mucor hiemalis Chaetomium globosum Trichoderma harzianum Penicillium chrysogenum Fusarium solani Rhizopus stolonifer Humicola grisea |

Litter degradation, release of C–N–P–K, extracellular enzymes | Prepare the soil, but some (Fusarium) inhibit germination |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) [29,30] |

Glomus intraradices Glomus etunicatum Acaulospora scrobiculata Gigaspora margarita |

Root symbiosis (arbuscules), P and N uptake, stress tolerance | Natural biopriming → improves germination and seedling vigor |

| Ectomycorrhizal Fungi (ECM) [29,30] |

Laccaria bicolor Russula cyanoxantha Suillus luteus Boletus pinophilus Amanita phalloides Tricholoma matsutake |

Mycelial network (Hartig net), mineral nutrition, inter-tree communication | Enhance germination and survival of forest species |

| Archaea [31] |

Nitrososphaera viennensis Candidatus Nitrosotenuis uzonensis Methanobacterium formicicum Methanocella arvoryzae Methanosaeta concilii Nitrososphaera gargensis |

Biogeochemical cycles (N, C, S, CH4), survival in extreme soils | Stabilize the ecosystem → indirect support of germination |

| Protists [32] |

Amoebozoa Apicomplexa Cercozoa Ciliophora Viruses Bacteriophages Phytoviruses Mycoviruses |

Regulation of microbial populations, symbiotic/parasitic interactions | Influence germination by balancing the microbiome |

| Cyanobacterial Algae (prokaryotes) [33,34,35] |

Nostoc commune Scytonema sp. Microcoleus vaginatus Tolypothrix spp. Anabaena spp. Calothrix spp. |

Photosynthesis, N2 fixation, polysaccharide production, lichenic symbioses | Improve nitrogen nutrition, soil humidity and stability → stimulated germination |

| Green Algae (Chlorophyta) [33] |

Chlorella vulgaris Klebsormidium flaccidum Scenedesmus obliquus |

Photosynthesis (chlorophyll A/B), biomass, exopolysaccharides | Biostimulants: accelerate germination and early growth |

| Yellow/Golden Algae (Xanthophyta, Chrysophyta, Diatoms) [33,36] |

Botrydium granulatum Ochromonas spp. Navicula spp. Eunotia spp. |

Carotenoid/fucoxanthin pigments, photosynthesis, exopolymers | Improve rhizospheric microhabitats, organic C input |

| Dinophyta & Cryptophyta Algae [33] |

Ceratium hirundinella Symbiodinium spp. Cryptomonas spp. |

Photosynthesis, antioxidant molecules, symbioses | Increase oxidative stress tolerance, germination under difficult conditions |

| Forest Species | Beneficial microbiomes | Mechanisms promoting growth | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus |

Paenibacillus spp. Pseudomonas spp. |

Pathogen suppression by enrichment of antagonistic bacteria and reduction of pathogens (such as Fusarium)/Decomposition of seed coats would facilitate radicle emergence and be associated with better germination. | [41] |

| Abies pindrow | Bacterial (30 species)/consortium; fungal (18 species) (729 isolates) | indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production-phytohormone, ammonia prodection, phosphate solubilization, Fusarium biocontrol | [42] |

| Pinus taeda | Arid community rich in Actinobacteria (Rubrobacterales) and Pleosporales fungi (dark septate fungi). | Stimulate germination via hormones and water retention, increase in root biomass (wet family), facilitation of nitrogen acquisition, but variable effects on photosynthesis and nutrition. | [43] |

|

Betula pendula Carpinus betulus Fagus sylvatica Fraxinus excelsior Larix decidua Picea abies Pinus sylvestris Quercus robur |

Russula spp. Laccaria spp. Tuber spp. Cenococcum geophilum Glomus spp. Claroideoglomus spp. Paraglomus spp. Pseudomonas spp. Bacillus spp. Burkholderia spp. Rhizobium spp. Actinobacteria divers |

Mycorrhization, nutrition (N, P), protection vs. pathogens (Pythium spp., Fusarium spp.), or on the contrary competition and infections. | [44] |

|

Eucalyptus largiflorens Eucalyptus camaldulensis Callitris glaucophylla |

Actinobacteria Proteobacteria Ascomycota Arbuscular mycorrhizae Aectomycorrhizal fungi |

Strong positive correlation between Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) and nitrogen-fixing plants/Secretion of phytohormones (auxins and cytokinins) stimulating germination/Promoting dormancy breaking by breaking the seed coat/Decomposition of organic matter to release nutrients available to the seed/Pathogen suppression | [45] |

| Trait | Pioneer Forest Species Seeds | Climax Forest Species Seeds |

|---|---|---|

| Typical seed size & number | Small seeds, often produced in large quantities such as Cecropia or produces tiny wind seeds in the millions. | Larger seeds with higher individual mass, produced in fewer numbers. |

| Nutrient reserves | Minimal reserves per seed, seedlings depend quickly on external resources. Low reserve content limits survival in shade. | Substantial nutrient reserves in the seed endosperm/cotyledons; can sustain seedling growth for extended periods. Large reserves support emergence in deep shade or through thick leaf litter. |

| Dormancy and seed bank | Often physiologically or physically dormant at shedding; form persistent soil seed banks. Dormancy is broken by disturbance cues signalling an open habitat. Many pioneers require light to germinate and can remain viable in soil for years until a gap occurs. | Frequently non-dormant or only briefly dormant; many are recalcitrant. Those with dormancy often require specific cues like prolonged cold or chemical scarification by gut passage. Generally, climax species seeds germinate in the next suitable season or perish, rather than forming long soil banks. |

| Germination conditions | Require high-light, fluctuating temperature, or other gap conditions for germination. Germinate rapidly once conditions are met, exploiting ephemeral resource availability. Seedlings are shade-intolerant, needing direct sunlight soon after germination. For instance, pioneer tree seeds often germinate only in canopy gaps or open clearings. | Can germinate under low light or stable understory conditions. Some exhibit slow or extended germination, and may germinate opportunistically over time. Seedlings are often shade-tolerant, capable of establishing under an intact canopy using seed reserves. Large-seeded climax species may germinate in deep shade and wait for later light availability. |

| Seed/seedling strategy | Emphasize quick establishment and fast early growth. Seedlings typically allocate more to shoot elongation to outgrow competitors. Survival is low if suitable gaps are absent shortly after germination. | Emphasize survival in competitive, resource-limited settings. Seedlings often exhibit slow growth but high survivorship, allocating to root development and defense. They can endure shaded conditions until a light gap appears years later, thanks to the energy reserves from large seeds. |

| Examples | Pioneer: Betula pendula, tiny, wind-dispersed seeds; Cecropia peltata light demanding tropical pioneer with dust-like seeds; Pinus sylvestris in early post-fire succession. | Climax: Fagus sylvatica, large nut-like seeds that germinate under forest canopy; Shorea spp. winged large seeds with no dormancy, germinating soon after dropping in the rainy season; Pouteria spp. recalcitrant seeds that lose viability if dried. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).