Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

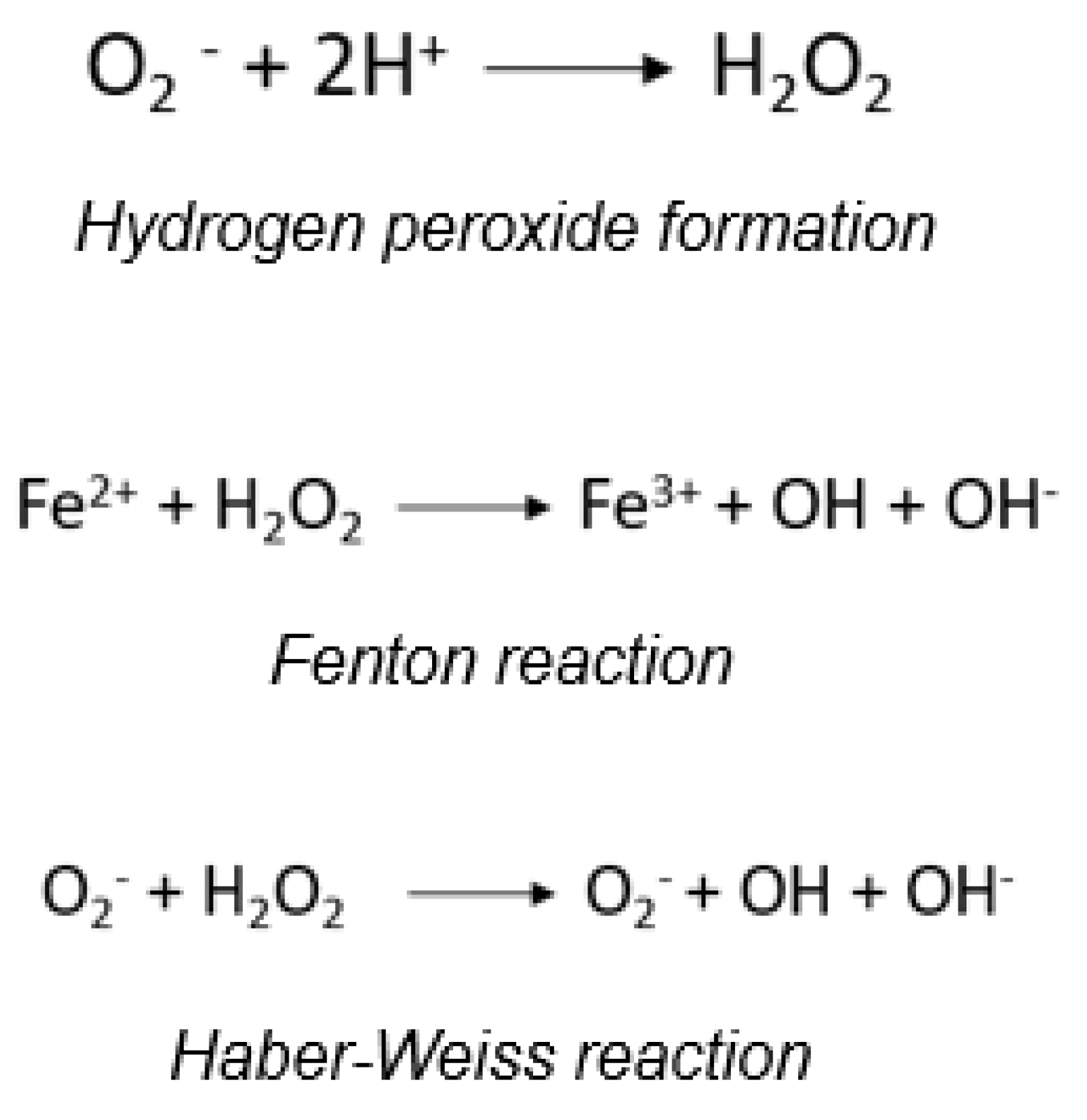

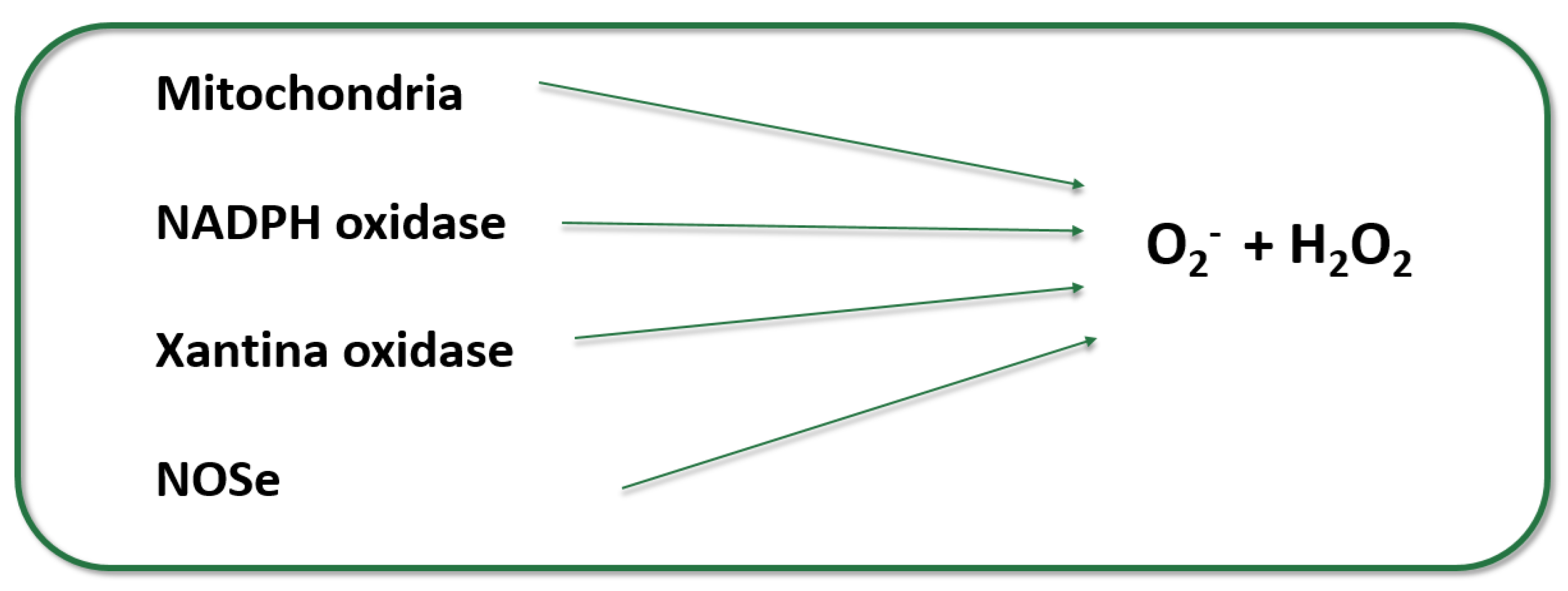

2. Genesis of Reactive Oxigen Species

- Mitochondria, where O2·- and H2O2 are produced from respiratory chain complexes I and II, representing 80% of basal O2·- production. Complexes I and III were traditionally considered most active in ROS generation, but recent studies indicate high activity in complex II as well, with current understanding suggesting similar activities between complexes I and II, and the highest activity in complex III [7,14].

- Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH oxidase or NOX), a multiprotein complex crucial for ROS production in various cells and tissues, especially phagocytic cells (neutrophils and macrophages), involved in pathogen elimination and inflammatory processes [15].

- Xanthine oxidase, an enzyme in purine catabolism catalyzing the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and then to uric acid, also associated with arteriosclerosis due to its activation of inflammatory pathways, such as NF-κB, which increase vascular inflammation and exacerbate endothelial damage, thereby promoting the progression of atherosclerosis [12].

- Nitric oxide (NO·) production by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which oxidizes L-arginine to citrulline in the presence of calmodulin to form NO·, using BH4 as a cofactor. BH4 oxidation can lead to non-enzymatic O2·- production, limiting eNOS's ability to produce free NO· in the absence of SOD. This enzyme is the major vascular producer of NO·, but OS can cause uncoupling of eNOS, resulting in O2·- production instead of NO·, due to BH4 oxidation and subsequent deficiency [16,17].

- Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), predominantly producing NO· from arginine, but BH4 deficiency promotes superoxide generation instead of NO·, similar to eNOS.

3. Antioxidant Systems and Mechanisms

- SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals (O2·-) to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Despite being more stable, H2O2 remains highly reactive. Different molecular variants of SOD have been identified: Cu/Zn-SOD (cytosolic, SOD1), Mn-SOD (mitochondrial, SOD2), and Cu/Zn-SOD (extracellular, SOD3) [2,9,22].

- Catalases catalyze the dismutation and peroxidation of H2O2 into water and oxygen. This is one of the fastest known catalytic activities, making catalases highly effective antioxidants against H2O2 [23].

- GPx removes hydroperoxides and organic peroxides, simultaneously oxidizing its physiological substrate, glutathione (GSH), to oxidized glutathione (GSSG). There are several molecular variants (GPx1 to GPx5), both selenium-dependent (tetrameric) and selenium-independent (dimeric) [24].

4. Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

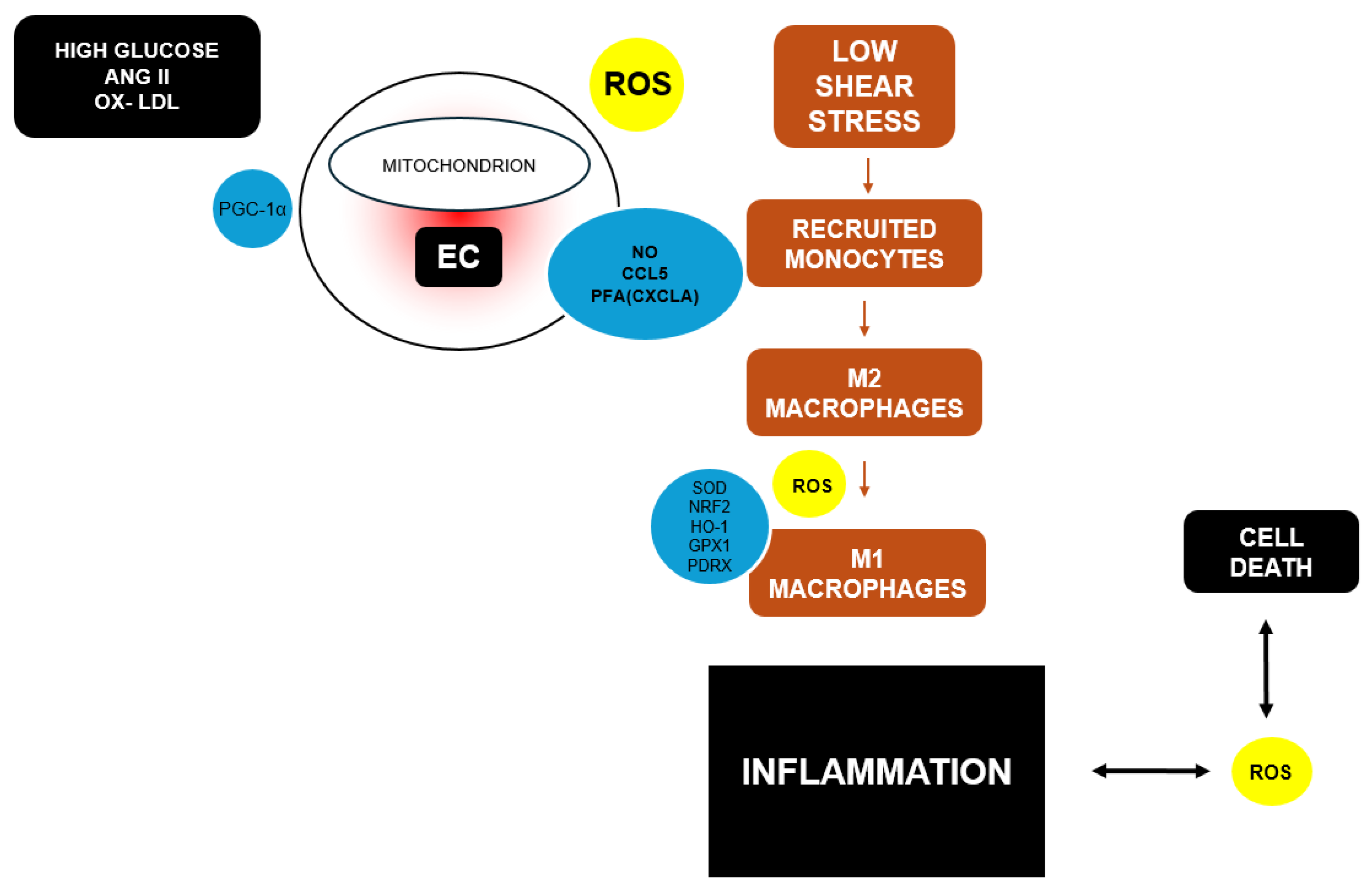

4.1. Endothelial Dysfunction

4.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

- Increased ROS Production: Continuous production of O2·- and other ROS in mitochondria increases oxidative damage to biomolecules, particularly nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). mtDNA instability is crucial in mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to mutagenic or cytotoxic effects and subsequent mutations after DNA replication. The accumulation of mtDNA mutations contributes to tissue function loss, including in the heart [40,41,42,43]. Animal models have confirmed this increased mtDNA instability [44].

- Calcium Homeostasis Imbalance: Mitochondria regulate intracellular calcium concentration, essential for cardiac contraction. Mitochondrial dysfunction disrupts calcium homeostasis, affecting cardiac contractility and potentially contributing to arrhythmias [45].

- Inflammation: Dysfunctional mitochondria can activate inflammatory responses in cardiac and other cardiovascular cells, contributing to the progression of diseases such as atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease. [47]

4.3. Oxidative Modifications Induced by ROS

- Initiation: ROS extract a hydrogen ion (H+) from a PUFA double bond, forming conjugated dienes (CD). Antioxidants in LDL particles initially halt this oxidation.

- Propagation: Once antioxidants are depleted, another H+ is abstracted by a peroxyl radical (LOO.) from a PUFA, forming lipid hydroperoxides. This increases LDL's negative charge due to Schiff base formation between positively charged amino groups and aldehyde groups, leading to macrophage recognition via scavenger receptors in arterial intima.

5. Consequences of Oxidative Stress: Atherosclerosis, Heart Failure, Ischemic Heart Disease, Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

5.1. Atherosclerosis

5.2. Hypertension

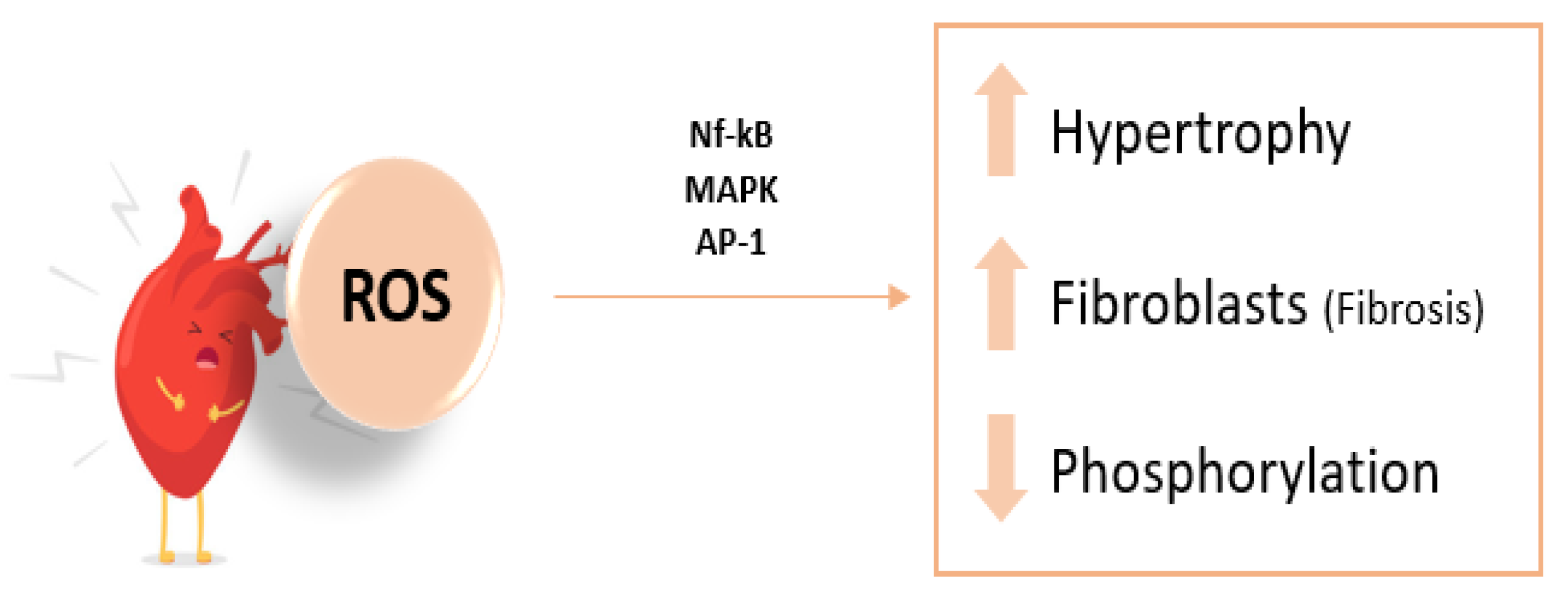

5.3. Heart Failure

5.4. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Parameters of OS in Cardiovascular Disease

- Be accessible in a target tissue or plasma, reflecting oxidative changes in a quantitative manner.

- Be a specific marker for the study of reactive species and independent of external factors.

- Be sensitive, robust, and reproducible.

- Be stable for sample handling, including processing, analysis, and storage.

6. Therapeutic Strategies to Reduce Oxidative Stress

7. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| OS | oxidative stress |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| eNOS | endotelial nitric oxide synthase |

| NF-kB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| BH4 | Tetrahydrobiopterine |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase |

| NOX | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSSG | oxidized glutathione |

| GSH | glutathione |

| HSPs | heat shock proteins |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ET-1 | endothelin-1 |

| Trx | thioredoxin |

| cGMP | guanosie 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate |

| ONOO-, | Peroxynitrite |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| mtDNA | mitocondrial DNA |

| oxLDL | oxidized low-density lipoproteins |

| PUFA | peroxidation of polyunsatured fatty acids |

| CD | cojugated dienes |

| LOO. | peroxyl radical |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| HNE | 4-hidroxynonenal |

| IL4 | interleukin-4 |

| IL1β | interleukin 1β |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesión molecule 1 |

| ICAM-1 | intercelular adhesión molecule 1 |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| ABCA1 | ATP binding casette |

| Apo A1 | apolipoprotein A1 |

| M1 | inflammatory macrophages |

| ANGII | angiotensin II |

| AP-1 | activator protein-1 |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| AGEs | advnaced glycation end-products |

| ACEIs | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| RAAS | renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| ASK1 | apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. |

References

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. OS: From basic research to clinical application. Am J Med. 1991, 91, S31–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free radicals in biology and medicine, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; 905p. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Species and Antioxidants. Redox Biology Is a Fundamental Theme of Aerobic Life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. ROS in metabolic and inflammatory signaling. Circ Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce ROS. Biochem J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, J.D. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem. 1969, 244, 6049–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C. Toxicity of iron and hydrogen peroxide: the Fenton reaction. Toxicol. Lett. 1995, 82–83, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrer, J.P. The Haber-Weiss reaction and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicology 2000, 149, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touyz, R.M.; Briones, A.M. ROS and Vascular Biology: Implications in Human Hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2011, 34, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griendling, K.K.; Sorescu, D.; Ushio-Fukai, M. NAD(P)H Oxidase: Role in Cardiovascular Biology and Disease. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial Formation of ROS. J. Physiol. 2003, 552 (Pt 2), 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, R.P.; Weissmann, N.; Schröder, K. Nox family NADPH oxidases: Molecular mechanisms of activation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 76, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric Oxide Synthases: Regulation and Function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, M.J.; Tatham, A.L.; Al-Wakeel, Y.; Warrick, N.; Hale, A.B.; Cai, S.; Channon, K.M.; Alp, N.J. Quantitative Regulation of Intracellular Endothelial Nitric-Oxide Synthase (eNOS) Coupling by Both Tetrahydrobiopterin-eNOS Stoichiometry and Biopterin Redox Status: Insights from Cells with Tet-Regulated GTP Cyclohydrolase I Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.G.; Polito, L.; Bolognesi, A. Xanthine oxidoreductase in atherosclerosis pathogenesis: Not only oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrader, M.; Fahimi, H.D. Peroxisomes and OS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1763, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryor, W.A.; Stone, K. Oxidants in Cigarette Smoke Radicals, Hydrogen Peroxide, Peroxynitrate, and Peroxynitritea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 686, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hao, C.; Cheng, Z.-M.; Zhong, Y. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Analysis of the Grapevine Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Family. Int. J. Genom. 2019, 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelikani, P.; Fita, I.; Loewen, P.C. Diversity of structures and properties among catalases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.R. The Glutathione Peroxidases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000, 57, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, B.; Higdon, J.V. Antioxidant Activity of Tea Polyphenols In Vivo: Evidence from Animal Studies. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3275S–3284S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Lupton, J.R.; Turner, N.D.; Fang, Y.-Z.; Yang, S. Glutathione Metabolism and Its Implications for Health. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudo, A.; Cabrera, L.; Amiano, P.; Ardanaz, E.; Barricarte, A.; Berenguer, T.; Chirlaque, M.D.; Dorronsoro, M.; Jakszyn, P.; Larrañaga, N.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intakes, dietary antioxidant nutrients, and total mortality in Spanish adults: findings from the Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Spain). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderwood, S.K.; Gong, J. Heat Shock Proteins Promote Cancer: It's a Protection Racket. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deanfield, J.E.; Halcox, J.P.; Rabelink, T.J. Endothelial Function and Dysfunction: Testing and Clinical Relevance. Circulation 2007, 115, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griendling, K.K.; FitzGerald, G.A. OS and Cardiovascular Injury: Part I: Basic Mechanisms and In Vivo Monitoring of ROS. Circulation 2003, 108, 1912–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.A. Antioxidants and coronary artery disease: from pathophysiology to preventive therapy. Coronary Artery Disease. marzo de 2015, 26, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Rotariu, D.; Babes, E.E.; Tit, D.M.; Moisi, M.; Bustea, C.; Stoicescu, M.; et al. OS – Complex pathological issues concerning the hallmark of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. agosto de 2022, 152, 113238. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, R.; ACidlowski, J. Apoptosis and glutathione: beyond an antioxidant. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. ROS, Vascular Noxs, and Hypertension: Focus on Translational and Clinical Research. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 20, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughan, A.; Harrison, D.; Dikalov, S. Abstract 1229: Molecular Mechanisms of Angiotensin II-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Linking Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage and Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction. Circulation 2007, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaconstantinou, J. The Role of Signaling Pathways of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Development of Senescence and Aging Phenotypes in Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, H.; Zeiher, A.M. Endothelial function in human coronary arteries in vivo. Focus on hypercholesterolemia. Hypertension 1991, 18, II90–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadel, G.S.; Horvath, T.L. Mitochondrial ROS Signaling in Organismal Homeostasis. Cell 2015, 163, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollman, A.P.; Moriya, M. Mutagenesis by 8-oxoguanine: an enemy within. Trends Genet. 1993, 9, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavli, B.; Otterlei, M.; Slupphaug, G.; Krokan, H. Uracil in DNA—General mutagen, but normal intermediate in acquired immunity. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tungekar, M.A.; Jung, M.-Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; Greenberger, J.S.; Stoyanovsky, D.A.; Kagan, V.E. Mitochondria targeting of non-peroxidizable triphenylphosphonium conjugated oleic acid protects mouse embryonic cells against apoptosis: Role of cardiolipin remodeling. FEBS Lett. 2011, 586, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wilhelmsson, H.; Graff, C.; Li, H.; Oldfors, A.; Rustin, P.; Brüning, J.C.; Kahn, C.R.; Clayton, D.A.; Barsh, G.S.; Thorén, P.; Larsson, N.G. Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Heart Specific Antisense DNA. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, G.W., 2nd; Scorrano, L. Two Close, Too Close: Sarcoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Crosstalk and Cardiomyocyte Fate. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, Å.B.; Gottlieb, R.A. Heart mitochondria: gates of life and death. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 77, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, J.; Haider, N.; Arbustini, E.; Chandrashekhar, Y. Mechanisms of Disease: apoptosis in heart failure—seeing hope in death. Nat. Clin. Pr. Cardiovasc. Med. 2006, 3, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschopp, J. Mitochondria: Sovereign of inflammation? Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisein, E.A. Biochemistry of free radicals and antioxidants. Sch Acad J Biosci. 2014, 2, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Orekhov, A.N. Peroxiredoxin family as redox-sensitive proteins implicated in cardiovascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, D.; Witztum, J.L. Is the oxidative modification hypothesis relevant to human atherosclerosis? Do the antioxidant trials conducted to date refute the hypothesis? Circulation. 2002, 105, 2107–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęgotek, A.; Skrzydlewska, E. The role of transcription factor Nrf2 in skin cells metabolism. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2015, 307, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá,, A. ; Díaz, M. Editorial: Impact of Lipid Peroxidation on the Physiology and Pathophysiology of Cell Membranes. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 423–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamanchi, N.R.; Runge, M.S. Redox signaling in cardiovascular health and disease. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 473–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D. Myeloperoxidase, inflammation, and dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2010, 4, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B. Site-specific oxidation of apolipoprotein A-I impairs cholesterol export by ABCA1, a key cardioprotective function of HDL. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2012, 1821, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.C.; Holme, R.L.; Chen, Y.; Thomas, M.J.; Sorci-Thomas, M.G.; Silverstein, R.L.; Pritchard KA,, J. r.; Sahoo, D. Acrolein Impairs the Cholesterol Transport Functions of High Density Lipoproteins. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Arnal-Levron, M.; Hullin-Matsuda, F.; Knibbe, C.; Moulin, P.; Luquain-Costaz, C.; Delton, I. In vitro oxidized HDL and HDL from type 2 diabetes patients have reduced ability to efflux oxysterols from THP-1 macrophages. Biochimie 2018, 153, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Obama, T.; Koba, S.; Takaki, T.; Iwamoto, S.; Aiuchi, T.; Kato, R.; Kikuchi, M.; Hamazaki, Y.; Itabe, H. Circulating oxidized LDL, increased in patients with acute myocardial infarction, is accompanied by heavily modified HDL. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, P.O.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Endothelial dysfunction: A marker of atherosclerotic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003, 23, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattoor, A.J.; Pothineni, N.V.K.; Palagiri, D.; Mehta, J.L. Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2017, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginckels, P.; Holvoet, P. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer: Role of Non-coding RNAs. Yale J Biol Med. 2022, 95, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook-Mills, J.M.; Marchese, M.E.; Abdala-Valencia, H. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Expression and Signaling During Disease: Regulation by Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidants. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1607–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantsila, E.; Wrigley, B.J.; Blann, A.D.; Gill, P.S.; Lip, G.Y. A contemporary view on endothelial function in heart failure. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2012, 14, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siwik, D.A.; Colucci, W.S. Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinases by Cytokines and Reactive Oxygen/Nitrogen Species in the Myocardium. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2004, 9, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercal, N.; Gurer-Orhan, H.; Aykin-Burns, N. Toxic metals and oxidative stress Part I: Mechanisms involved in metal-induced oxidative damage. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001, 1, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, A.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Polyphenols and atherosclerosis: A critical review of clinical effects on LDL oxidation. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 184, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hold, G.L.; El-Omar, M.E. Genetic aspects of inflammation and cancer. Biochem. J. 2008, 410, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja, G. Mitochondrial Oxygen Radical Generation and Leak: Sites of Production in States 4 and 3, Organ Specificity, and Relation to Aging and Longevity. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1999, 31, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, O.; Forbes, P.B. Challenges and advances in quantum dot fluorescent probes to detect reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 862, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E. Biomarkers of lipid peroxidation in clinical material. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, M.C.; Stahl, W.; Eichler, O.; Niestroj, I.; Sies, H. Profiles of antioxidants in human plasma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001, 30, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.; Mahajan, N.; Sah, S.; Nath, S.K.; Paudyal, B. Oxidative stress and its biomarkers in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 21, 23–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, F. Biomarkers of oxidative stress. In Systems Biology of Free Radicals and Antioxidants; Leher, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Ed.; Springer-Verlag Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B.; Kaur, H. Hydroxylation of salicylate and phenylalanine as assays for hydroxyl radicals: A cautionary note visited for the third time. Free Radic Res. 1997, 27, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Boyle, D.L.; Manning, A.M.; Firestein, G.S. AP-1 and NF-kB Regulation in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Murine Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Autoimmunity 1998, 28, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant glutathione. Vitamins Hormones. 2023, 121, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franco, C.; Sciatti, E.; Favero, G.; Bonomini, F.; Vizzardi, E.; Rezzani, R. Essential Hypertension and Oxidative Stress: Novel Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci-Çekiç, S.; Özkan, G.; Avan, A.N.; Uzunboy, S.; Çapanoğlu, E.; Apak, R. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 209, 114477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöttker, B.; Saum, K.-U.; Jansen, E.H.J.M.; Boffetta, P.; Trichopoulou, A.; Holleczek, B.; Dieffenbach, A.K.; Brenner, H. Oxidative Stress Markers and All-Cause Mortality at Older Age: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2014, 70, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijhoff, J.; Winyard, P.G.; Zarkovic, N.; Davies, S.S.; Stocker, R.; Cheng, D.; Knight, A.R.; Taylor, E.L.; Oettrich, J.; Ruskovska, T.; et al. Clinical Relevance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1144–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.; Verma, H.K.; Lakkakula, S.; Merchant, N.; Kadir, F.; Rahman, S.; Jeffree, M.S.; Lakkakula, B.V.K.S.; Rao, P.V. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress Tethered to Cardiovascular Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9154295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013, 158, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne GL, Yin H, Hardy KD, Davies SS, Roberts LJ 2nd. Isoprostane generation and function. Chem Rev. 2011, 111, 5973–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.; Bobak, M.; Anusruti, A.; Jansen, E.H.J.M.; Pająk, A.; Tamosiunas, A.; Saum, K.-U.; Holleczek, B.; Gao, X.; Brenner, H.; et al. Association of serum markers of oxidative stress with myocardial infarction and stroke: pooled results from four large European cohort studies. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2018, 34, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P. Redefining Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha, K.; Haider, R.; Pathak, A.; Yar, M.S. Medicinal prospects of antioxidants: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 178, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroev, S.A.; Gluschenko, T.S.; Tjulkova, E.I.; Spyrou, G.; Rybnikova, E.A.; Samoilov, M.O.; Pelto-Huikko, M. Preconditioning enhances the expression of mitochondrial antioxidant thioredoxin-2 in the forebrain of rats exposed to severe hypobaric hypoxia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 78, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J.; Pérez-Vizcaíno, F. Protección cardiovascular con flavonoides: enigma farmacocinético. Ars Pharm. 2015, 56, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vizcaino, F.; Duarte, J.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Endothelial function and cardiovascular disease: Effects of quercetin and wine polyphenols. Free. Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebati, S.K.; Tomassoni, D.; Mannelli, L.D.C.; Amenta, F. Effect of treatment with the antioxidant alpha-lipoic (thioctic) acid on heart and kidney microvasculature in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2015, 38, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, F.; Dong, M.; Ren, Y. Research progress of quercetin in cardiovascular disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1203713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Romero, M.; Gómez-Guzmán, M.; Tamargo, J.; Pérez-Vizcaino, F.; Duarte, J. Cardiovascular effects of flavonoids. CMC. 2019, 26, 6991–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, M.A.; Chun, O.K. Vitamin C and Heart Health: A Review Based on Findings from Epidemiologic Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzon Dos Santos, J.; Schaan De Quadros, A.; Weschenfelder, C.; Bueno Garofallo, S.; Marcadenti, A. OS biomarkers, nut-related antioxidants, and cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Duarte, J. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAltawili, A.; Altawili, M.; Alwadai, A.M.; Alahmadi, A.S.; AAlshehri, A.M.; Muyini, B.H.; Alshwwaf, A.R.; Almarzooq, A.M.; AAlqarni, A.H.; Alruwili, Z.A.L.; et al. An Exploration of Dietary Strategies for Hypertension Management: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e50130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothineni, N.V.K.; Karathanasis, S.K.; Ding, Z.; Arulandu, A.; Varughese, K.I.; Mehta, J.L. LOX-1 in Atherosclerosis and Myocardial Ischemia: Biology, genetics, and modulation. JACC 2017, 69, 2759–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 57, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, K.; Altmann, H.M.; Straub, A.C.; Isenberg, J.S. Nitric oxide: what’s new to NO? American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 1 de marzo de 2017, 312, C254–C262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapakos, G.; Youreva, V.; Srivastava, A.K. Cardiovascular protection by curcumin: molecular aspects. Indian J Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 49, 306–315. [Google Scholar]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).