Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

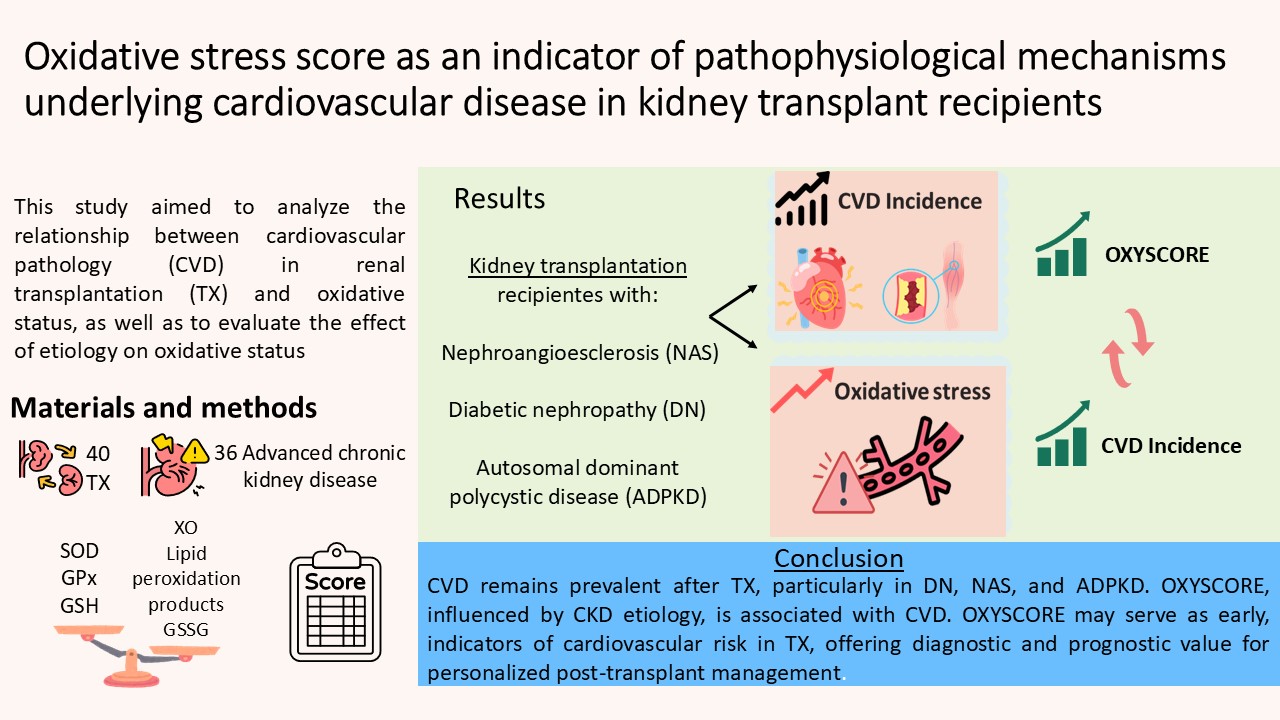

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Blood Collection and Preparation

2.3. Leukocytes Density Gradient Separation

2.4. Oxidative Stress Parameters

2.4.1. Xanthine Oxidoreductase Activity

2.4.2. Glutathione Peroxidase Activity

2.4.3. Lipid Peroxidation Assay

2.4.4. Glutathione Content Assay

2.4.5. Superoxide Dismutase Activity

2.4.6. Protein Content Assay

2.4.7. OXY-SCORE Index Determination

2.5. Metabolic Syndrome Diagnosis

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Baseline Characteristics

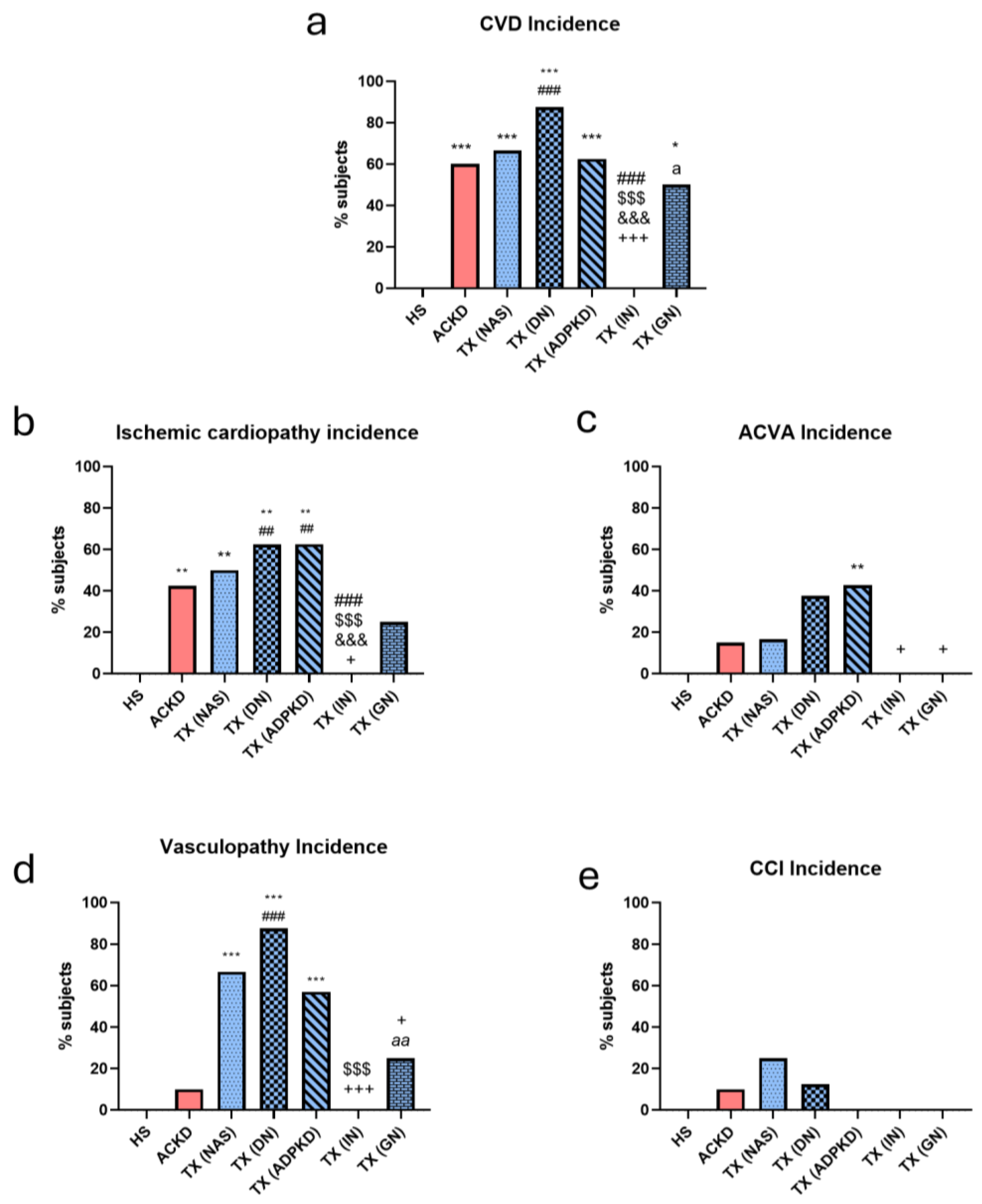

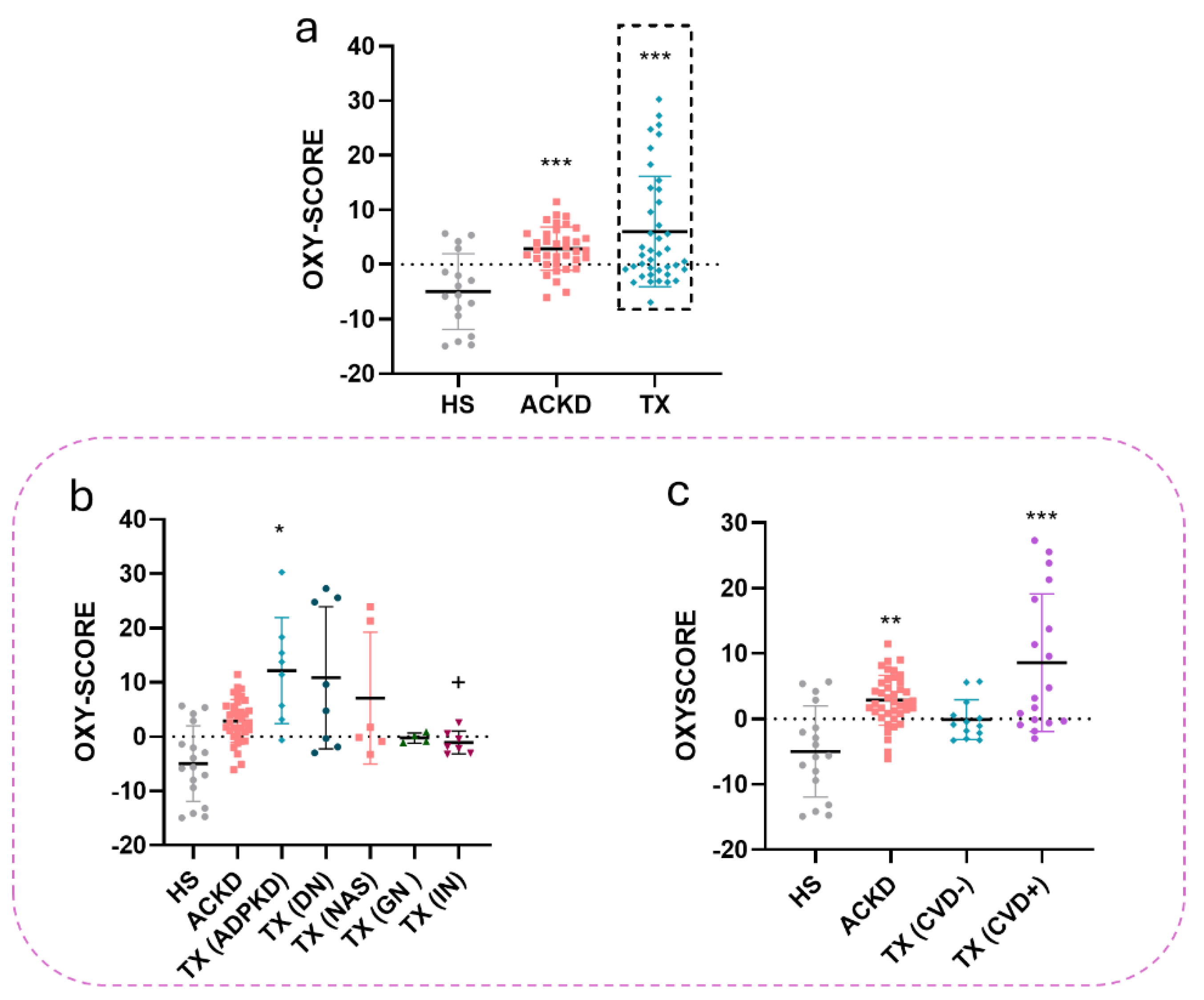

3.2. Cardiovascular Disease Incidence Was Influenced by Etiology

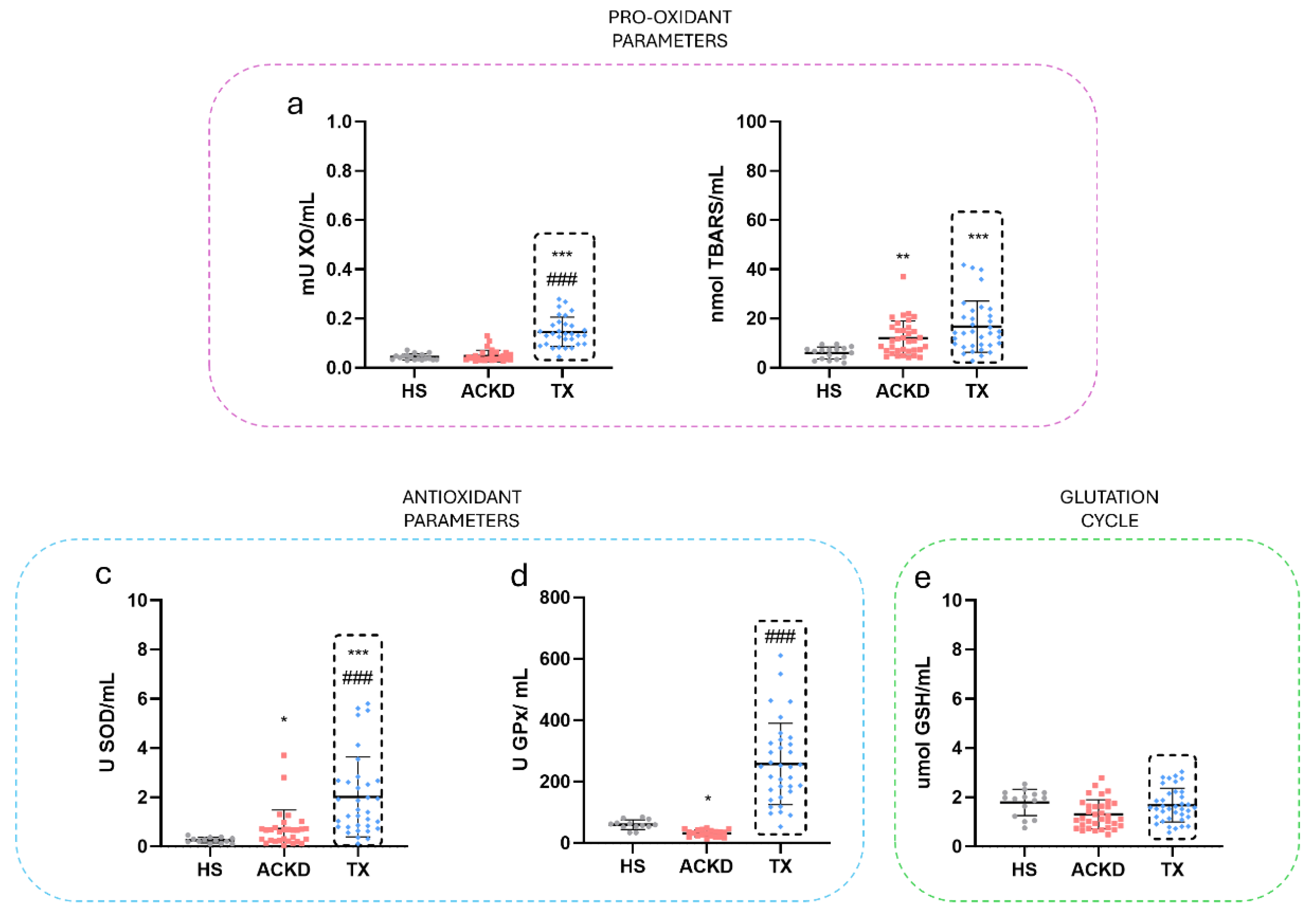

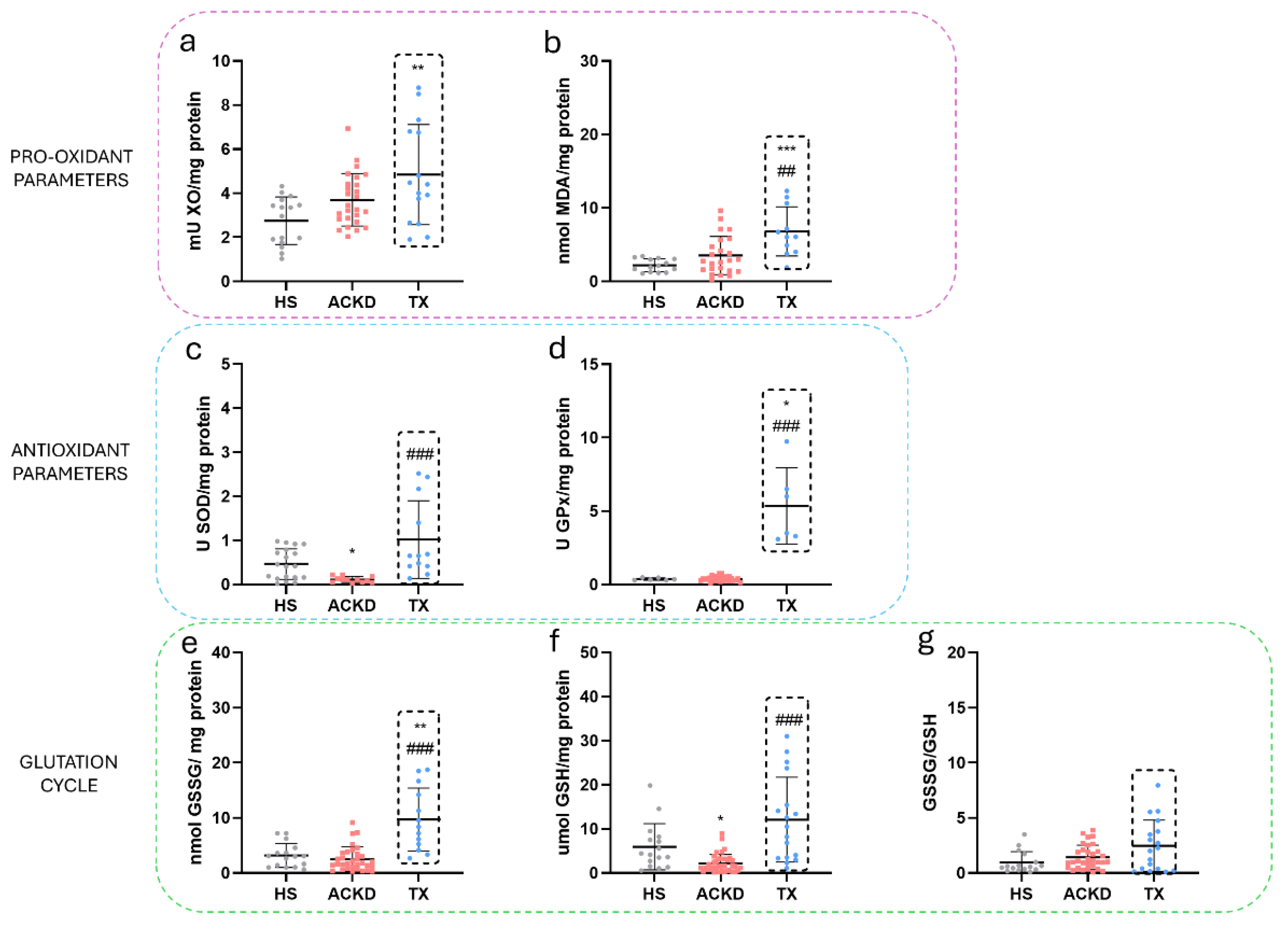

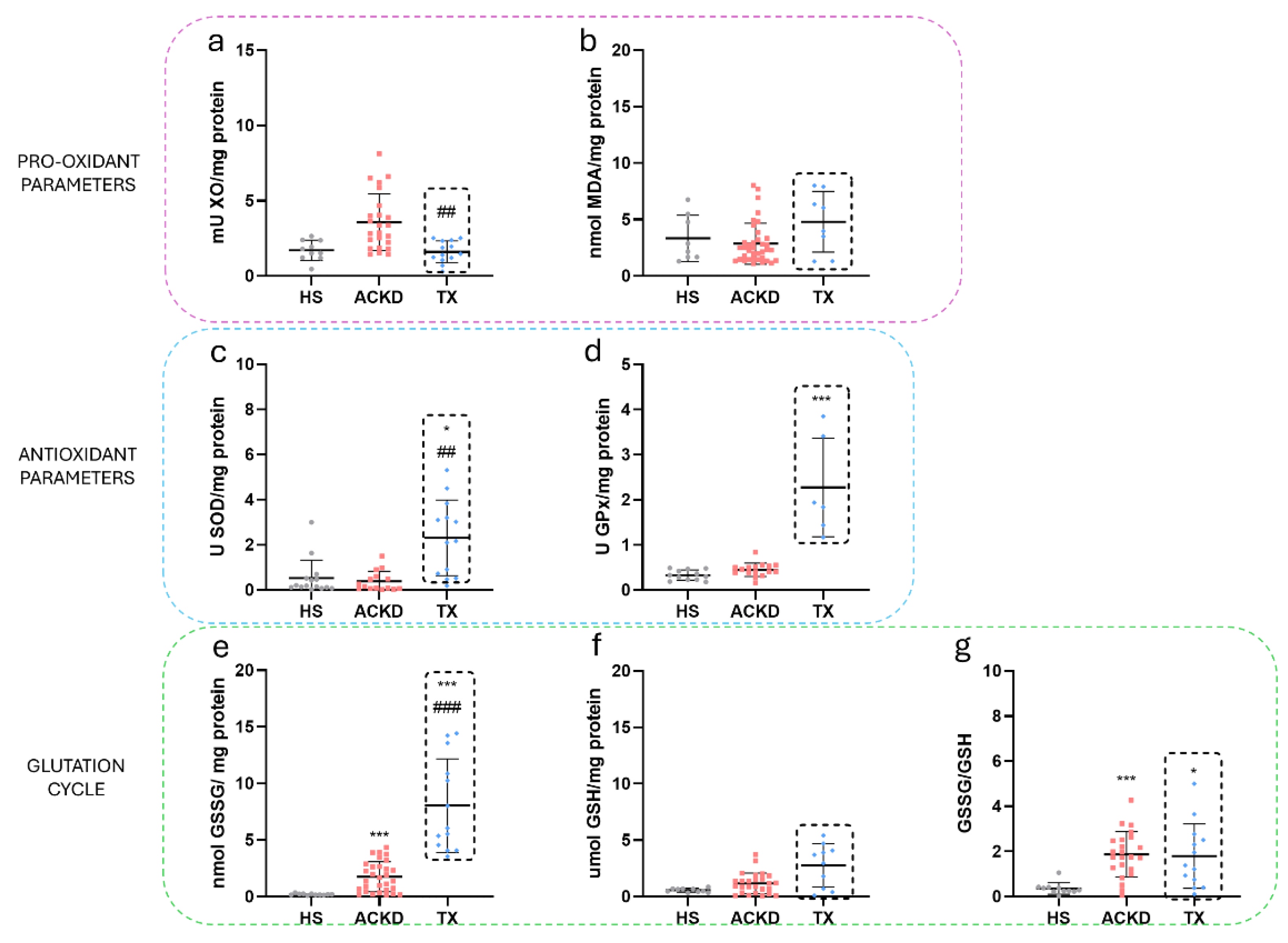

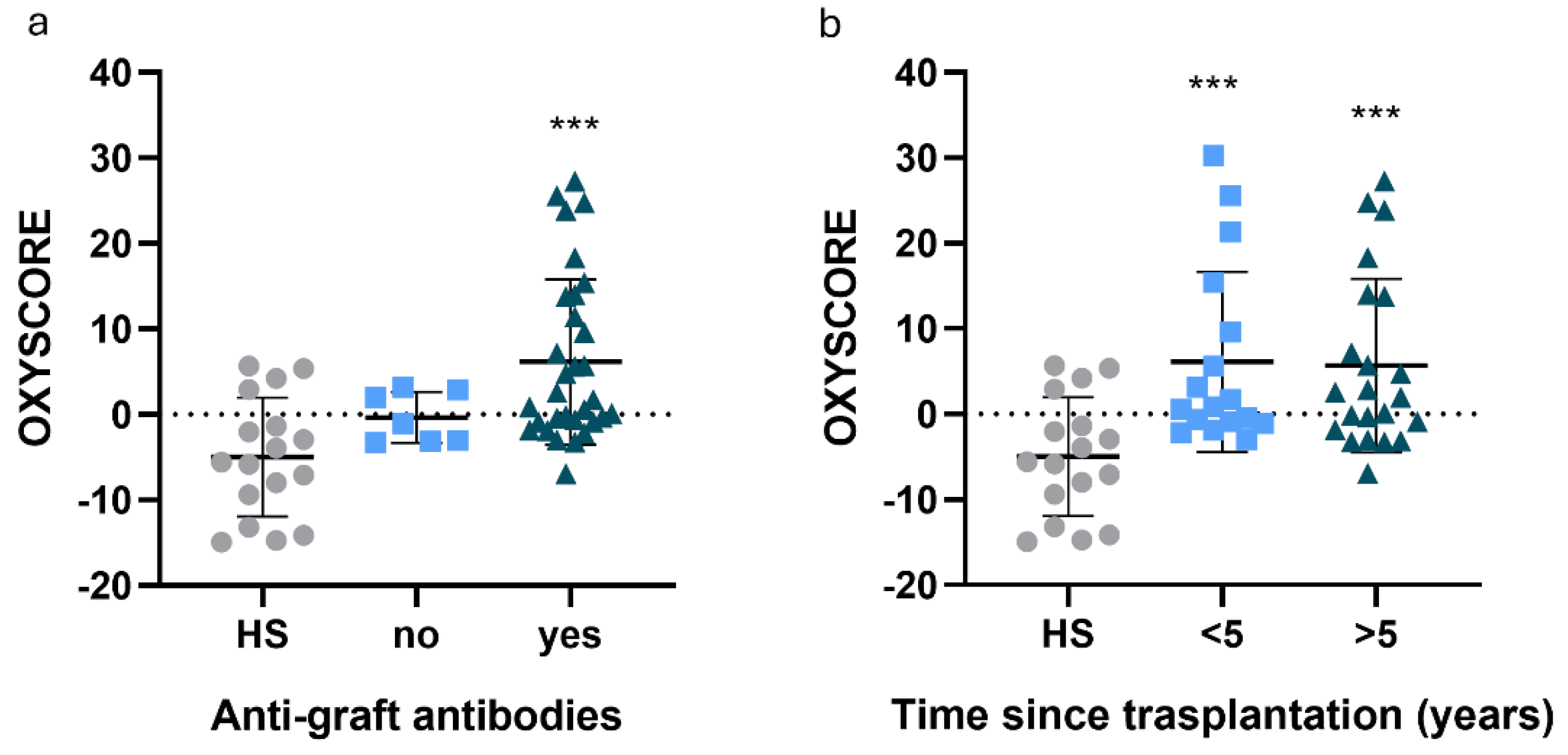

3.3. Alterations in Oxidative Stress Markers Were Detected in Plasma and Immune Cell Populations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACKD | advanced chronic kidney disease |

| ACVA | acute cardiovascular accident |

| ADPKD | autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease |

| AH | arterial hypertension |

| BCA | bicinchoninic acid |

| BI | body mass index |

| CCI | chronic cardiac insufficiency |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| DN | diabetic nephropathy |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | glutathione disulfide |

| GN | glomerulonephritis |

| HD | haemodialysis |

| HS | healthy subjects |

| IN | interstitial nephritis |

| LDL | low density lipoprotein |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MN | mononuclear leukocytes |

| NAS | nephroangioesclerosis |

| OPT | o-phtalaldehyde |

| PBS | phosphate buffered solution |

| PD | peritoneal dialysis |

| PMN | polymorphonuclear leukocytes |

| RAAS | renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| TBARS | thiobarbituric acid reactive substance |

| TG | triglicerides |

| TX | kidney transplantation |

| XO | xanthine oxidase |

Appendix A

| HS | TX (NAS) | TX (DN) | TX (ADPKD) | TX (IN) | TX (GN) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XO Activity (mU/mL) | 0.04±0.012 | 0.29±0.39 | 0.17±0.15 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.44±0.44 | 1.8±0.06 |

| SOD Activity (U/mL) | 0.65±1.47 | 1.55±1.38 | 4.1±3.5 | 3.8±3.2 | 10.1±17.8 | 1.7±0.7 |

| GPx Activity (U/mL) | 60.2±15.6 | 701.8±1053.27 | 290.1±293.6 | 1075±1969 | 835±1073 | 342.9±141 |

| TBARS (nmol/mL) | 5.9±2.4 | 37±39 | 20.9±10.4 | 39.9±49.2 | 33.7±48.05 | 13.9±3.3 |

| GSH (umol/mL) | 1.7±0.53 | 1.6±0.8 | 1.4±0.5 | 1.7±0.5 | 2.1±1.33 | 1.8±0.9 |

| HS | TX (NAS) | TX (DN) | TX (ADPKD) | TX (IN) | TX (GN) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XO Activity (mU/mL) | 2.7±1.1 | 4. 8±1.3 | 2±0.5 | 5.1±3.4 | 6.4±2.8 | 0.80±0.014 |

| SOD Activity (U/mL) | 0.4±0.3 | 1.1±0.9 | 2.1±2 | 9.2±8.3 | 18±4 | 0.46 |

| GPx Activity (U/mL) | 0.8±1.1 | 1.7±1.6 | 8.7±1 | 5.4±7.7 | 1.5±1.3 | 0.12±0.08 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 3.5±2.9 | 6.73±1 | 42.3±33.8 | 15.7±15.4 | 6.4±3.6 | 8.037±2.016 |

| GSH (umol/mL) | 5.9±5.2 | 27±18.3 | 13.7±11.7 | 46.8±87.1 | 336±112 | 3.215±2.51 |

| GSSG (umol/mL) | 3.1±2.1 | 37.1±40.3 | 17±16.9 | 53.8±80.6 | - | - |

| GSSG/GSH | 0.9±0.9 | 2.9±4.3 | 2.8±2.5 | 2.1±2.1 | - | - |

| HS | TX (NAS) | TX (DN) | TX (ADPKD) | TX (IN) | TX (GN) | |

| XO Activity (mU/mL) | 2.4±1.8 | 1.8±0.5 | 1.6±0.66 | 5.7±4.8 | 1.9±0.9 | - |

| SOD Activity (U/mL) | 0.5±0.8 | 2.2±2.1 | 3.1±1.7 | 9.5±12.7 | 8.2±1.2 | 2.1±1.18 |

| GPx Activity (U/mL) | 0.3±0.1 | 1±1.1 | 1.4±1.4 | 0.47±0.06 | 1.8±0.82 | 0.57±0.28 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 3.3±2.1 | 3.5±1 | 3.9±1 | 7.9±0.06 | 6.3±1.2 | - |

| GSH (umol/mL) | 1.3±2.4 | 3.7±1.8 | 9.6±16.1 | 15.6±15.4 | 3.3±1.1 | - |

| GSSG (umol/mL) | 0.2±0.07 | 7.6±5.7 | 7.2±3.9 | 17.8±9.9 | - | - |

| GSSG/GSH | 0.4±0.3 | 3.3±1.8 | 14.8±25.9 | 1.7±0.7 | - | - |

| HS | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus+mycophenolate) | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus+sirolimus) | TX (corticoid+mycophenolate+cyclosporin) | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus) | TX (tacrolimus+mycophenolate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XO Activity (mU/mL) | 0.04±0.01 | 0.4±0.6 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.1±0.1 |

| SOD Activity (U/mL) | 0.6±1.5 | 4.7±9.7 | 1.9 | 2.51 | 0.79±0.28 | 3.8±3 |

| GPx Activity (U/mL) | 60.2±15.6 | 810±1284 | 100.7 | 249.89 | 133.6±45.9 | 238.3±62.6 |

| TBARS (nmol/mL) | 6±2.5 | 25.2±32.4 | 104.4 | 39.84 | 33.12±44.63 | 20.6±14.7 |

| GSH (umol/mL) | 1.8±0.5 | 1.7±0.6 | 1.53 | 1.2 | 1.09±0.5 | 1.2±0.6 |

| HS | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus+mycophenolate) | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus+sirolimus) | TX (corticoid+mycophenolate+cyclosporin) | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus) | TX (tacrolimus+mycophenolate) | |

| XO Activity (mU/mL) | 2.7±1.1 | 3.7±1.6 | 6.8 | - | 7.6±1.2 | 8.8 |

| SOD Activity (U/mL) | 0.4±0.3 | 2.6±3.9 | 1.4 | 0.42 | 2.7±2.9 | 10.9±12 |

| GPx Activity (U/mL) | 0.8±1.1 | 3.9±5.2 | 0.39 | 0.9 | 0.61 | 1.6 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 3.5±3 | 11.2±11.4 | 7.16 | - | 6.7 | 39.3±38.1 |

| GSH (umol/mL) | 6±5.2 | 33.5±67.5 | 7.2 | 3 | 19±12 | 9±6 |

| GSSG (umol/mL) | 3.2±2.1 | 30.4±58.5 | 43 | 11.31 | 44,8±54.7 | 34.7±15.7 |

| GSSG/GSH | 1±0.9 | 1.9±1.7 | 0.16 | 3.77 | 4.1±5.5 | 4.3±1.5 |

| HS | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus+mycophenolate) | TX (corticoid+mycophenolate+cyclosporin) | TX (corticoid+tacrolimus) | TX (tacrolimus+mycophenolate) | TX (tacrolimus+mycophfenolate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XO Activity (mU/mL) | 2.4±1.8 | 1.6±0.7 | 9.2 | 2.52 | 1.8±0.8 | 1.1±0.5 |

| SOD Activity (U/mL) | 0.5±0.8 | 3.4±2.5 | 18.6 | 3.84 | 1.7±2.1 | 0.9 |

| GPx Activity (U/mL) | 0.3±0.1 | 0.7±0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2.4±0.1 | 0.4 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 3.3±2.1 | 4.4±3.4 | 7.9 | 6.04 | 3.5 | - |

| GSH (umol/mL) | 1.3±2.4 | 7.5±11.7 | 26.5 | - | 2.3±2.3 | 2.1±2.8 |

| GSSG (umol/mL) | 0.2±0.1 | 7.4±3.6 | 24.9 | 14.4 | 8.9±7.6 | 6.7±1.9 |

| GSSG/GSH | 0.4±0.3 | 3.9±4.7 | 0.9 | - | 3.1±0.8 | 53.8 |

References

- House, A.A.; Wanner, C.; Sarnak, M.J.; et al. Heart failure in chronic kidney disease: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, L.E.; Trompet, S.; Mooijaart, S.P.; et al. The association of kidney function and cognitive decline in older patients at risk of cardiovascular disease: A longitudinal data analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshani, W.V.D.; de Namor, A.F.D.; Silva, S.R.P. Rising of a global silent killer: critical analysis of chronic kidney disease of uncertain aetiology (CKDu) worldwide and mitigation steps. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2023, 45, 2647–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Tang, S.C.W. Personalized immunosuppression after kidney transplantation. Nephrology. 2022, 27, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, C.; Oliva, C.; Yuste, C.; et al. Oxidative stress in patients with advanced ckd and renal replacement therapy: The key role of peripheral blood leukocytes. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Cavalca, V.; Tremoli, E. OXY-SCORE: a global index to improve evaluation of oxidative stress by combining pro- and antioxidant. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, A.; Quelhas-Santos, J.; Sampaio, S.; et al. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with cerebrovascular events in pre-dialysis CKD patients: a prospective study. Life. 2021, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraj, M.; Kusnierz-Cabala, B.; Dumnicka, P.; et al. Redox balance correlates with nutritional status among patients with end-stage renal disease treated with maintenance hemodialysis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecerska-Heryć, E.; Heryć, R.; Dutkiewicz, G.; et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase activity in platelet-poor and rich plasma as an oxidative stress indicator in patients requiring renal replacement therapy. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, L.; Iglesias, E.; Pastor, M.C.; et al. Inflammation and oxidation: do they improve after kidney transplantation? Relationship with mortality after transplantation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017, 49, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Calderón, M.; Sotomayor, C.G.; Gans, R.O.B.; et al. Post-transplantation plasma malondialdehyde is associated with cardiovascular mortality in renal transplant recipients: a prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020, 35, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymanian, T.; Hamid, G.; Arefi, M.; et al. Non-diabetic renal disease with or without diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: clinical predictors and outcome. Ren Fail. 2015, 37, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaswami, J.; Mathew, R.O.; Parasuraman, R.; et al. Cardiovascular disease in the kidney transplant recipient: epidemiology, diagnosis and management strategies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019, 34, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klawitter, J.; Reed-Gitomer, B.Y.; McFann, K.; et al. Endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014, 307, F1198–F1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.T.; Mohammed, Z.I. The Impact of glomerulonephritis on cardiovascular disease: Exploring pathophysiological links and clinical implications. J Rare Cardiovasc Dis. 2025, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hervas, S.; Real, J.T.; Ivorra, C.; et al. Increased plasma xanthine oxidase activity is related to nuclear factor kappa beta activation and inflammatory markers in familial combined hyperlipidemia. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010, 20, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushiyama, A.; Okubo, H.; Sakoda, H.; et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase is involved in macrophage foam cell formation and atherosclerosis development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012, 32, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, X.; Chen, D.; et al. The clinical value of serum xanthine oxidase levels in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Redox Biol. 2023, 60, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, R.; Hamasaki, Y.; Komaru, Y.; et al. Plasma xanthine oxidoreductase is associated with carotid atherosclerosis in stable kidney transplant recipients. Nephrology. 2022, 27, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, R.; Ramirez, R.; de Sequera, P.; et al. Citrate dialysate does not induce oxidative stress or inflammation in vitro as compared to acetate dialysate. Nefrologia. 2017, 37, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamode, N.; Bestard, O.; Claas, F.; et al. European Guideline for the Management of Kidney Transplant Patients With HLA Antibodies: By the European Society for Organ Transplantation Working Group. Transplant Int. 2022, 35, 10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.; Darrah, E.; Rosen, A. Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O’Dell JR, editors. Kelley and Firestein’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 831–45. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, U.; Sharma, A.; et al. Evaluation of oxidant and antioxidant status in living donor renal allograft transplant recipients. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016, 413, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Timón, I.; Sevillano-Collantes, C.; Segura-Galindo, A.; et al. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Have all risk factors the same strength? World J Diabetes. 2014, 5, 444–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C.; Halliwell, B. Mini-Review: oxidative stress, redox stress or redox success? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 502, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.M.; Ruiz, M.C.; Ruiz, N.; et al. Modulation factors of oxidative status in stable renal transplantation. Transplantation Proceedings. 2005, 37, 1428–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younus, H. Therapeutic potentials of superoxide dismutase. Int. J. Health Sci. 2018, 12, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zachara, B.A.; Wlodarczyk, Z.; Andruszkiewicz, J.; et al. Glutathione and glutathione peroxidase activities in blood of patients in early stages following kidney transplantation. Renal Failure. 2005, 27, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.C.; Medina, A.; Moreno, J.M.; et al. Relationship between oxidative stress parameters and atherosclerotic signs in the carotid artery of stable renal transplant patients. Transplantation Proceedings. 2005, 37, 3796–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasai, P.K.; Shrestha, B.; Orr, A.W.; et al. Decreases in GSH:GSSG activate vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) in human aortic endothelial cells. Redox Biology. 2018, 19, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras Benito, M. Nephroangiosclerosis: an update. Hipertension y Riesgo Vascular. 2023, 40, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassègue, B.; Griendling, K.K. NADPH oxidases: Functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010, 30, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigagli, E.; Raimondi l Mannucci, E.; et al. Lipid and protein oxidation products, antioxidant status and vascular complications in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. 2012, 12, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, S.M.; Guedes, G.S.; da Fonseca, L.J.; et al. Characterization of blood oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: Increase in lipid peroxidation and SOD activity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 819310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, A.; Kaul, K.; Brüggemann, J. , et al Lower serum extracellular superoxide dismutase levels are associated with polyneuropathy in recent-onset diabetes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeshara, K.A.; Diwan, A.G.; Jagtap, T.R.; et al. Relationship between plasma glycation with membrane modification, oxidative stress and expression of glucose trasporter-1 in type 2 diabetes patients with vascular complications. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.B.; Devuyst, O.; Eckardt, K.U.; et al. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): Executive summary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney International. 2015, 88, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, R.L.; Vassmer, D.; Magenheimer, B.S.; et al. Oxidant stress and reduced antioxidant enzyme protection in polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletti, A.; Bruschi, M.; Kajana, X.; et al. Mechanisms Limiting Renal Tissue Protection and Repair in Glomerulonephritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praga, M.; Sevillano, A.; Gonzalez, E. Changes in the aetiology, clinical presentation and management of acute interstitial nephritis, an increasingly common cause of acute kidney injury. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2015, 30, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegaard, A.O.; Jacobs, D.R.; Sanchez, O. A. Oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2016, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, V.; Lobysheva, I.; Gérard, L.; et al. Oxidative stress-induced endothelial dysfunction and decreased vascular nitric oxide in COVID-19 patients. EbioMedicine. 2022, 77, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is associated with left ventricular geometry and heart failure in patients with cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, A.M.; Carrero, J.J.; Wolf, M.; et al. Serum Uric Acid and Mortality Risk Among Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney International Reports, 2020, 5, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybka, J.; Kupczyk, D.; Kedziora-Kornatowska, K.; et al. Glutathione-related antioxidant defense system in elderly patients treated for hypertension. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2011, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damy, T.; Kirsch, M.; Khouzami, L.; et al. Glutathione deficiency in cardiac patients is related to the functional status and structural cardiac abnormalities. PLoS ONE. 2009, 4, e4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | HS (n=18) | ACKD (36) | TX (n=40) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years±sd) | 54.83±16.25 | 61.16±16.48 | 56.22±13.55 |

| Gender (Women (%)) | 12 (52.2) | 14 (38.9) | 13 (32.5) |

| CVD (n (%)) | 0 (0) | 23 (63.9)** | 20 (50)** |

| Ischemic cardiopathy (n (%)) | 0 (0) | 16 (44.4)** | 16 (40)** |

| Acute cardiovascular accident (n (%)) | 0 (0) | 6 (16.7) | 9 (22.5) |

| Vasculopathy (n (%)) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.1) | 18 (45)** # |

| Chronic heart failure (n (%)) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (5) |

| Arterial hypertension (n(%)) | 1 (5.8) | 32 (88.9)*** | 39 (97.5)*** |

| Beta-blockers (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 9 (25)* | 11 (27.5)* |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.3) | 3 (7.5) |

| Calcium channel blockers (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 11 (30.6)* | 13 (32.5)* |

| Diuretics (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.1) | 3 (7.5) |

| ACE inhibitors (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.3) | 9 (22.5) |

| Dyslipidemia (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 27 (75)*** | 21 (52.5)*** |

| Statins (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 26 (72.2)*** | 17 (73.9)* |

| Diabetes mellitus (n(%)) | 1 (5.5) | 16 (44.4)** | 16 (40)** |

| Insulin (n(%)) | 1 (5.5) | 9 (25)* | 9 (22.5)** |

| SGLT2 inhibitors (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 14 (46.7)** | 1 (2.5) ## |

| Biguanide (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5) |

| DPP-4 inhibitors (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 1 (2.5) |

| Hyperuricemia (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 25 (69.4)*** | 8 (20)* # |

| Allopurinol (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 21 (58.3)** | 11 (27.5)** # |

| Erythropoietin (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 30 (100)*** | 8 (20)## |

| Metabolic syndrome (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 9 (25)* | 6 (15) |

| COPD (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 7 (17.5)# |

| Liver disease (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.3) | 8 (20) |

| Cancer (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 11 (55)## |

| Antibodies against transplantation (n(%)) | - | - | 21 (52.5) |

| Immunosuppressive treatment (n(%)) | - | - | 36 Corticosteroid (90) 38 Tacrolimus (95) 32 Mycophenolate (80) 5 Everolimus (12.5) |

| Time since transplantation (n(%)) | - | - | 17 less than 5 years (42.5) 23 more than 5 years (57.5) |

| Aetiology of CKD (n(%)) | - | 7 NAS (19.4) 13 DN (36.4) 1 ADPKD (11.1) 6 IN (16.7) 6 GN (16.7) |

6 NAS (15) 8 DN (20) 8 ADPKD (20) 7 IN (17.5) 4 GN (10) 7 Others (17.5) |

| Tobacco (n(%)) | 4 (22.2) | 9 (25) | 10 (25) |

| Mortality rate (n(%)) | 0 (0) | 13 (36.1)* | 3 (7.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).