1. Introduction

The aureolic acid class of antibiotics includes mithramycin, chromomycin A3, and olivomycin A, and was recognized back in the 1960s as having significant antitumor properties [

1,

2]. Studies in primary cultures derived from human brain tumors revealed that more than 50% of tumor cells were susceptible to these antibodies [

3]. Among the aureolic-class antibiotics, olivomycin A (also known as olivomycin I), produced by

Streptomyces olivoreticuli, has attracted particular interest due to its intricate aglycone structure, which includes both a disaccharide and a trisaccharide branch. The primary intracellular target of olivomycin A is DNA, specifically GC-rich regions within the minor groove, where it binds through hydrogen interactions between the chromophore of the antibiotic and the 2-amino group of guanine (G4) in the DNA structure [

4,

5,

6]. The consensus 5’-GG-3’ or 5’-GC-3’ binding sequences for olivomycin A are commonly found in the regulatory segments of genes, which also act as potential recognition sites for transcription factors and are associated with many essential biological pathways [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Given the ability of olivomycin A to bind to DNA in these regions, it is unsurprising that this antibiotic can obstruct polymerase function and block subsequent replication and transcription.

Beyond its ability to bind DNA, olivomycin A may also embody its anticancer properties by directly and/or indirectly acting on cellular protein targets. It has been shown to significantly affect a variety of cellular proteins, including heat shock proteins and transcription factors [

11,

12,

13]. Olivomycin A may interfere with the DNA-dependent enzyme topoisomerase I, and can induce cytotoxicity in murine leukemia and human T lymphoblastic cells at nanomolar concentrations [

14,

15]. A relatively recent study showed that olivomycin A and its derivative, olivamide, inhibit DNA methyltransferase activity to hinder DNA methylation, which is an essential process in epigenetic regulation [

16]. In addition, olivomycin A suppresses p53-dependent transcription and promotes apoptosis in human tumor cells [

17]. While the tumor suppressor p53 is well-known for its involvement in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and DNA repair, knowledge remains limited beyond the context of olivomycin A-inhibited, p53-dependent apoptosis. The ability of olivomycin A to modulate p53 could be crucial for its anticancer effects. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying these effects, particularly the impact of olivomycin A on p53 modulation and downstream signaling, remain inadequately explored. Here, we aimed to address this research gap.

To this end, we employed two human renal cell carcinoma cell lines, A-498 cells expressing wild-type p53 and 786-O cells carrying loss-of-function mutant p53 and the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes [

18]. We aimed to investigate the mechanism underlying the anticancer activity of olivomycin A in these genetically distinct backgrounds. Our results revealed that the antibiotic triggered apoptosis through p53-dependent mechanisms, activating the intrinsic pathway in A-498 cells and engaging both intrinsic and extrinsic cascades in 786-O cells. Notably, olivomycin A induced more pronounced DNA damage and promoted extensive mitochondrial loss via mitophagy in the p53-mutated background. Together, our findings identify olivomycin A as a promising therapeutic candidate that suppresses EMT and enforces mitochondrial quality control to inhibit the growth of renal cancer cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

Olivomycin A was produced by

Streptoverticillum cinnamoneum at the pilot facility of Gause Institute of New Antibiotics (Moscow, Russia). The compound was purified to 95% purity, as confirmed by reverse-phase HPLC [

15].

2.2. Cell Culture and Reagents

Anti-Snail, anti-N-cadherin, anti-ZO-1, anti-VCAM-1, anti-FLIP, anti-caspase 8, anti-Bid, anti-Puma, anti-Bak, anti-Bcl-2, anti-caspase 9, anti-PARP, anti-phospho-p53, anti-phospho-Histone H2A.X, anti-PINK1, and anti-Parkin were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). The anti-E-cadherin antibody was from Servicebio (Hubei, China). Anti-cytochrome c antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-β-actin antibody was from Millipore Corp. (Temecula, CA, USA). Other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA).

A-498 human kidney carcinoma cells (derived from kidney tissues) were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids and 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate. 786-O human primary renal cell adenocarcinoma cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium containing 4.5 g/L glucose, 10 mM HEPES, and 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% air.

2.3. Wound Healing Assays

Cell migration was evaluated using a two-well culture insert. Inserts were placed in six-well plates, and 100 µl of cell suspension was added to each well at densities of 7.5 × 104 A498 cells or 5.5 × 104 786-O cells. After incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 16 h to allow attachment, 1 ml of fresh medium was added to the surrounding well area, and inserts were carefully removed to create a cell-free gap. Images of the initial wound area (0 h) were acquired immediately after the insert removal. Cells were then treated with olivomycin A and incubated for 8 h under the same culture conditions, followed by image acquisition to document cell migration into the wound area. Wound closure was quantified using ImageJ software, with the wound area at 0 h defined as 100%. The remaining wound area after 8 h was expressed as a percentage, with smaller residual wound areas indicating greater migratory activity.

2.4. Transwell Assay

The integrity of the transwell inserts was verified by adding 300 µl PBS the day before the experiment to check for leakage. After 24 h of Olivomycin A treatment, 2 × 104 cells suspended in 200 µl serum-free medium were seeded into the upper chamber and allowed to adhere to the membrane for 20 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The lower chamber was then filled with 600 µl medium containing 10% FBS as a chemoattractant, and cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. Following incubation, the medium was removed from both chambers, and cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 100% methanol (200 µl in the upper chamber, 600 µl in the lower chamber) for 10 min. After two washes with PBS, cells were stained overnight at room temperature with Giemsa solution diluted 1:10 in ddH2O (200 µl upper chamber, 600 µl lower chamber). The next day, the stain was removed, membranes were washed with ddH2O and soaked for ~2 h, air-dried, and imaged under a light microscope. Migrated cells were quantified using ImageJ software.

2.5. Cell Impedance Measurements

Cell proliferation was monitored using the xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experimental parameters, including E-Plate identification, cell line, seeding density, and drug treatment conditions, were first configured in the RTCA software. Each well of the E-Plate was filled with 75 µl of fresh culture medium, avoiding bubble formation, and the plate was placed in the instrument for background impedance measurement. Subsequently, 75 µl of culture medium containing 4,000 786-O cells was added to each well (final volume, 150 µl), taking care to prevent bubbles and to avoid disturbing the microelectrode surface. After gentle mixing, the E-Plate was inserted into the RTCA instrument and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 16 h to allow cell attachment. Drug treatment was carried out by pausing the RTCA software and carefully aspirating 75 µl of supernatant from each well without disturbing adherent cells. An equal volume (75 µl) of fresh medium containing olivomycin A at the indicated concentrations was then added. Plates were gently mixed, returned to the RTCA instrument, and continuously monitored for impedance-based cell index measurements.

2.6. Colony-Forming Assay

Cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 1,200 A498 cells or 500 786-O cells per well in 2 ml of fresh culture medium and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 48 h to allow attachment. Afterward, the medium was replaced with 3 ml of fresh culture medium containing olivomycin A at the indicated concentrations, and cells were cultured for an additional 9 days with medium changes every 3 days. At the end of treatment, colonies were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 100% methanol for 10 min, and stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 1–3 min. Excess dye was removed by rinsing with ddH2O until the background was clear, and plates were air-dried before scanning. Colony formation was quantified using ImageJ software, and results were expressed as the relative colony area per well.

2.7. Apoptosis Determination

Cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 A498 cells or 2.5 × 105 786-O cells per well in 2 ml of fresh culture medium and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 16 h to allow attachment. Cells were then treated with olivomycin A at the indicated concentrations, while 0.03% H2O2 was used as a positive control (PC), and incubated for 24 h. After treatment, culture supernatants were collected, cells were washed once with 1 ml PBS, detached with trypsin, and harvested by centrifugation (1,000 rpm, 1 min). Pellets were washed with PBS, transferred to 1.5 ml tubes, and centrifuged again (2,000 rpm, 3 min). PC samples were divided into three groups for Annexin V single staining, PI single staining, or Annexin V/PI double staining, while all other groups were subjected to double staining. For staining, 10× Annexin V binding buffer was diluted to 1×, and dyes were diluted 1:1000 in 1× buffer. Cells were resuspended in 500 µl staining solution and incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. After gentle resuspension and filtration through a cell strainer to avoid clogging, samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer using Annexin V-FITC and PI channels. Unstained cells served as negative controls to define gating, followed by compensation using single-stained samples. Apoptosis was quantified as the percentage of Annexin V-positive and/or PI-positive cells using a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX LX flow cytometer (Brea, CA, USA).

2.8. Measurement of Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Activity

Cells were seeded on sterilized coverslips placed in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 A-498 cells or 1 × 105 786-O cells per well and cultured overnight at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 to allow attachment. Cells were then treated with olivomycin A at the indicated concentrations for 72 h. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 1× Fixative Solution (prepared in ddH2O) for 15 min at room temperature. For senescence detection, cells were incubated with freshly prepared β-galactosidase staining solution (1× Staining Solution supplemented with 100× Solution A, 100× Solution B, and 1 mg/ml X-gal solution) and placed in a dry incubator at 37°C overnight without CO2. Stained cells were examined and imaged under a light microscope.

2.9. Measurement of Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Oxidative stress was assessed by detecting intracellular hydrogen peroxide using 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA). This nonpolar, cell-permeable dye is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to form the nonfluorescent H2-DCF, which is subsequently oxidized by peroxides to yield the highly fluorescent DCF. For staining, sterilized coverslips were placed into 24-well plates containing 1 ml of fresh medium, and cells were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells per well. After overnight incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to allow attachment, cells were washed once with 1 ml of PBS and once with 0.5 ml of 1× buffer (diluted in ddH2O), followed by incubation with 0.5 ml of 1× buffer containing the indicated concentrations of olivomycin A. After 15 min of drug exposure, cells were stained with 4 µM DCFDA for 45 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2 under light-protected conditions. Cells were washed twice with 1× buffer before imaging, and coverslips were inverted onto glass slides for fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence images were acquired using an excitation/emission setting of 488/535 nm.

2.10. Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells were seeded on sterilized coverslips placed in 24-well plates (2.2 × 104 A498 cells or 2.0 × 104 786-O cells per well) and cultured overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to allow attachment, followed by treatment with olivomycin A at the indicated concentrations. For live-cell staining, cells were incubated with 20 nM MitoTracker Green for 30 min or 50 nM LysoTracker Red for 5 min at 37 °C in the dark. After washing with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked with buffer containing 10% FBS and 3% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies, diluted in blocking buffer according to manufacturer recommendations, were applied for 1 h, followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500) for an additional 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with 1 µg/ml DAPI for 5 min. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides with mounting medium, edges sealed with nail polish, and stored at 4 °C in the dark until confocal fluorescence microscopy.

2.11. Western Blot Analysis

Cell extracts were prepared in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 ng/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. Protein concentrations were determined, and equal amounts of protein (40 µg per sample) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH, USA). Membranes were blocked with nonfat milk solution for 30 min, washed, and incubated with primary antibody. After washing with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS) to remove unbound antibody, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h. Bound antibodies were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

2.12. Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments. Comparisons between groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an appropriate post hoc test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Kidney cancer encompasses several histologically and molecularly distinct subtypes and ranks as the 14th most common malignancy worldwide, with approximately 180,000 deaths reported in 2020 [

20,

21,

22]. Among the subtypes of kidney cancer, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the predominant form, accounting for nearly 90% of all renal malignancies. Genomic studies have identified at least 11 recurrent mutated genes implicated in RCC pathogenesis, including those encoding Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor and PTEN [

23,

24]. Despite advances in surgical resection, targeted therapies, and immune checkpoint inhibitors, the current treatment options for RCC remain limited by both intrinsic and acquired resistance, and durable responses are achieved in only a fraction of patients. This therapeutic challenge underscores the need for agents with novel action mechanisms.

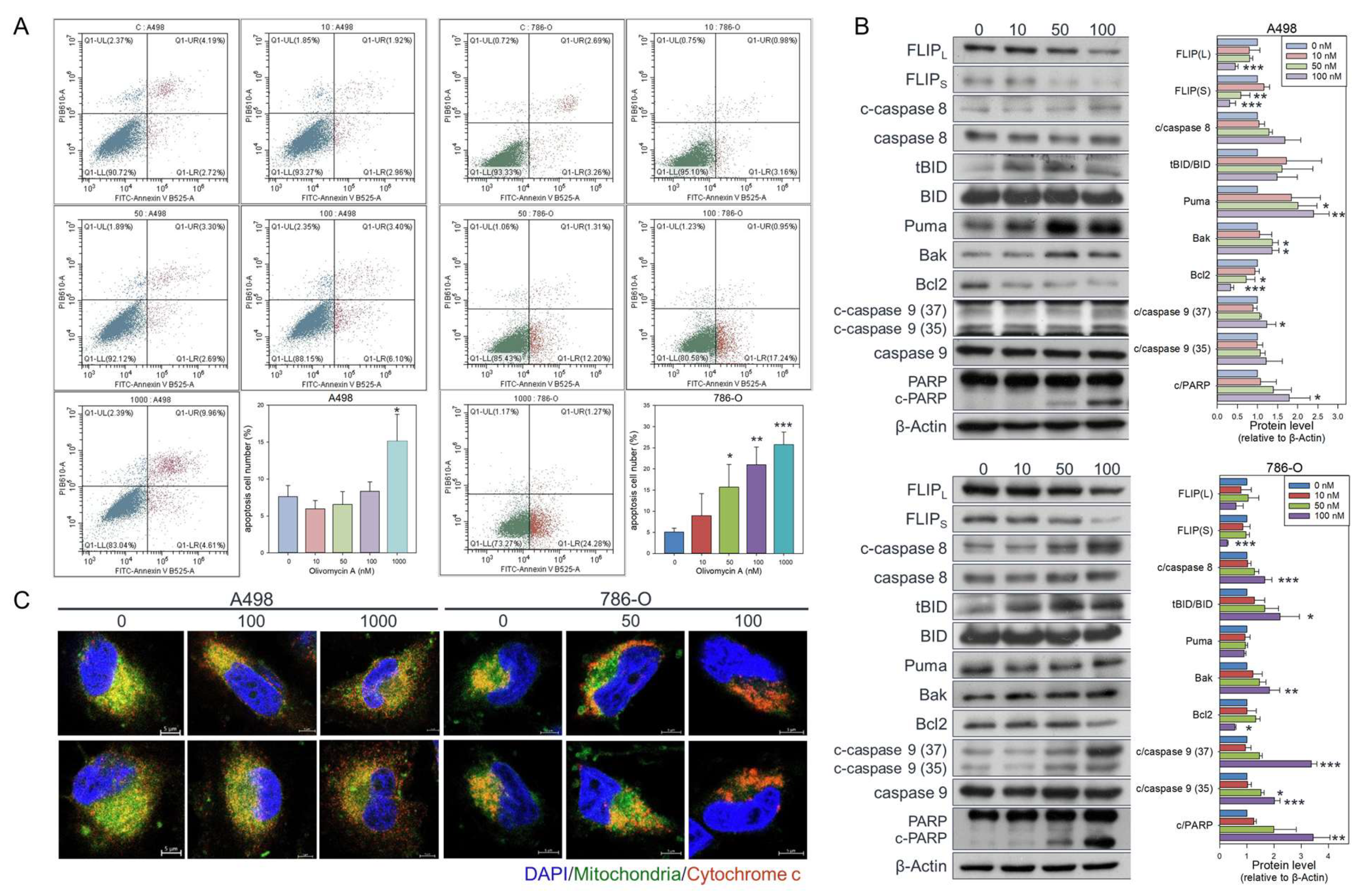

Using two representative RCC cell lines, we herein show that olivomycin A, an aureolic acid-class antibiotic, exerts multifaceted anticancer effects by simultaneously impairing migration capacity and inducing both apoptosis and mitophagy. These multiple actions are clinically significant, given that RCC cells are notoriously resistant to apoptosis and prone to metastasis, both of which contribute to the poor prognosis of this disease [

25,

26]. By targeting both survival and metastatic programs, olivomycin A may offer a therapeutic advantage over agents that act on a single-pathway, particularly in tumors harboring p53, VHL, and PTEN mutations, which constitute a subset of aggressive RCCs [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Interestingly, we observed that the cellular response to olivomycin A is strongly influenced by the p53 status. In p53-wild-type A-498 cells, the intrinsic apoptotic pathway predominated, as reflected by upregulation of Puma, Bak, and active caspase-9. In contrast, 786-O cells harboring concurrent mutations in p53 and PTEN engaged both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, under olivomycin A treatment, as evidenced by caspase-8 activation, Bid truncation, and FLIP suppression. Beyond its role in restraining oncogenic signaling, PTEN also modulates p53 stability and activity through phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms [

31]. Meanwhile, p53 itself can enhance PTEN expression at the transcriptional level [

32,

33,

34]. This reciprocal regulation forms a critical tumor-suppressive axis that directly governs apoptotic sensitivity. Disruption of this axis, as exemplified in 786-O cells, activates diverse apoptotic signaling cascades and may render cells particularly vulnerable to agents that impose both DNA damage and oxidative stress.

A further striking observation was the preferential induction of mitochondrial damage and mitophagy in 786-O cells with dual p53 and PTEN mutations. Increasing evidence suggests that PTEN and p53 are closely linked to the regulation of mitophagy. Under genotoxic stress, mitophagy normally functions as a compensatory quality-control mechanism to eliminate damaged mitochondria, thereby preserving mitochondrial integrity and facilitating DNA repair [

35,

36]. However, p53 exerts dual and context-dependent effects: Nuclear p53 can repress the transcription of stress-response genes, such as that encoding BNIP3 [

37], which mediates receptor-driven mitophagy, whereas cytosolic p53 directly binds Parkin and prevents its mitochondrial translocation, to inhibit canonical PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy [

38,

39]. In parallel, PTEN, particularly its PTENα isoform, facilitates Parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria, thereby promoting PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy and maintaining mitochondrial integrity [

40,

41]. Loss of PTEN disrupts this process, leading to defective mitophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, and exacerbated ROS accumulation. Likewise, gain-of-function mutations in p53 can further dysregulate the cellular redox balance and amplify oxidative stress [

42]. Consistent with these mechanisms, we observed that severe DNA damage and ROS accumulation in p53/PTEN-deficient 786-O cells coincided with mitochondrial collapse and elevated lysosomal activity, which are hallmarks of mitochondrial stress-induced clearance. Importantly, this convergence of excessive ROS burden, defective apoptotic control, and impaired mitophagy suggests a

therapeutically exploitable vulnerability, through which compounds such as olivomycin A may selectively overwhelm mitochondrial quality-control mechanisms in aggressive RCC.

Figure 1.

Structure of olivomycin A.

Figure 1.

Structure of olivomycin A.

Figure 2.

Effects of olivomycin A on colony formation, proliferation, and senescence in renal cancer cells. (A, B) Representative images and quantification of colony formation assays showing reduced clonogenic survival in A-498 (A) and 786-O (B) cells following treatment with olivomycin A. Colony numbers were determined and documented. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. There was a significant reduction in colony numbers in olivomycin A-treated cells compared with untreated controls (*p <0.05, *** p <0.001). (C) Cell proliferation was dynamically monitored using the xCELLigence system in 786-O cells, demonstrating concentration-dependent growth inhibition. (D) Representative images of senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining showing induction of cellular senescence upon olivomycin A treatments. Doxorubicin was used as a positive control.

Figure 2.

Effects of olivomycin A on colony formation, proliferation, and senescence in renal cancer cells. (A, B) Representative images and quantification of colony formation assays showing reduced clonogenic survival in A-498 (A) and 786-O (B) cells following treatment with olivomycin A. Colony numbers were determined and documented. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. There was a significant reduction in colony numbers in olivomycin A-treated cells compared with untreated controls (*p <0.05, *** p <0.001). (C) Cell proliferation was dynamically monitored using the xCELLigence system in 786-O cells, demonstrating concentration-dependent growth inhibition. (D) Representative images of senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining showing induction of cellular senescence upon olivomycin A treatments. Doxorubicin was used as a positive control.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects of olivomycin A on cell migration assessed by wound healing assays and transwell chamber assays. (A, B) The cell monolayer was scratched with a pipette tip and treated with different concentrations of olivomycin A or vesicles as a control in A-498 (A) and 786-O (B) cells. Wound closure was examined at 0 and 8 h after scratching using inverted light microscopy. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown. Quantitative analysis of wound closures is presented in the histogram. Values represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p <0.05, ***p <0.001 vs. control). (C, D) Cell migration was further assessed by transwell chamber assays. Migrated cells were fixed, stained, and counted in A-498 (C) and 786-O (D) cells. Quantitative analysis of migrated cells is shown in the histogram. Values represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p <0.05, ***p <0.001 vs. control).

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects of olivomycin A on cell migration assessed by wound healing assays and transwell chamber assays. (A, B) The cell monolayer was scratched with a pipette tip and treated with different concentrations of olivomycin A or vesicles as a control in A-498 (A) and 786-O (B) cells. Wound closure was examined at 0 and 8 h after scratching using inverted light microscopy. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown. Quantitative analysis of wound closures is presented in the histogram. Values represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p <0.05, ***p <0.001 vs. control). (C, D) Cell migration was further assessed by transwell chamber assays. Migrated cells were fixed, stained, and counted in A-498 (C) and 786-O (D) cells. Quantitative analysis of migrated cells is shown in the histogram. Values represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p <0.05, ***p <0.001 vs. control).

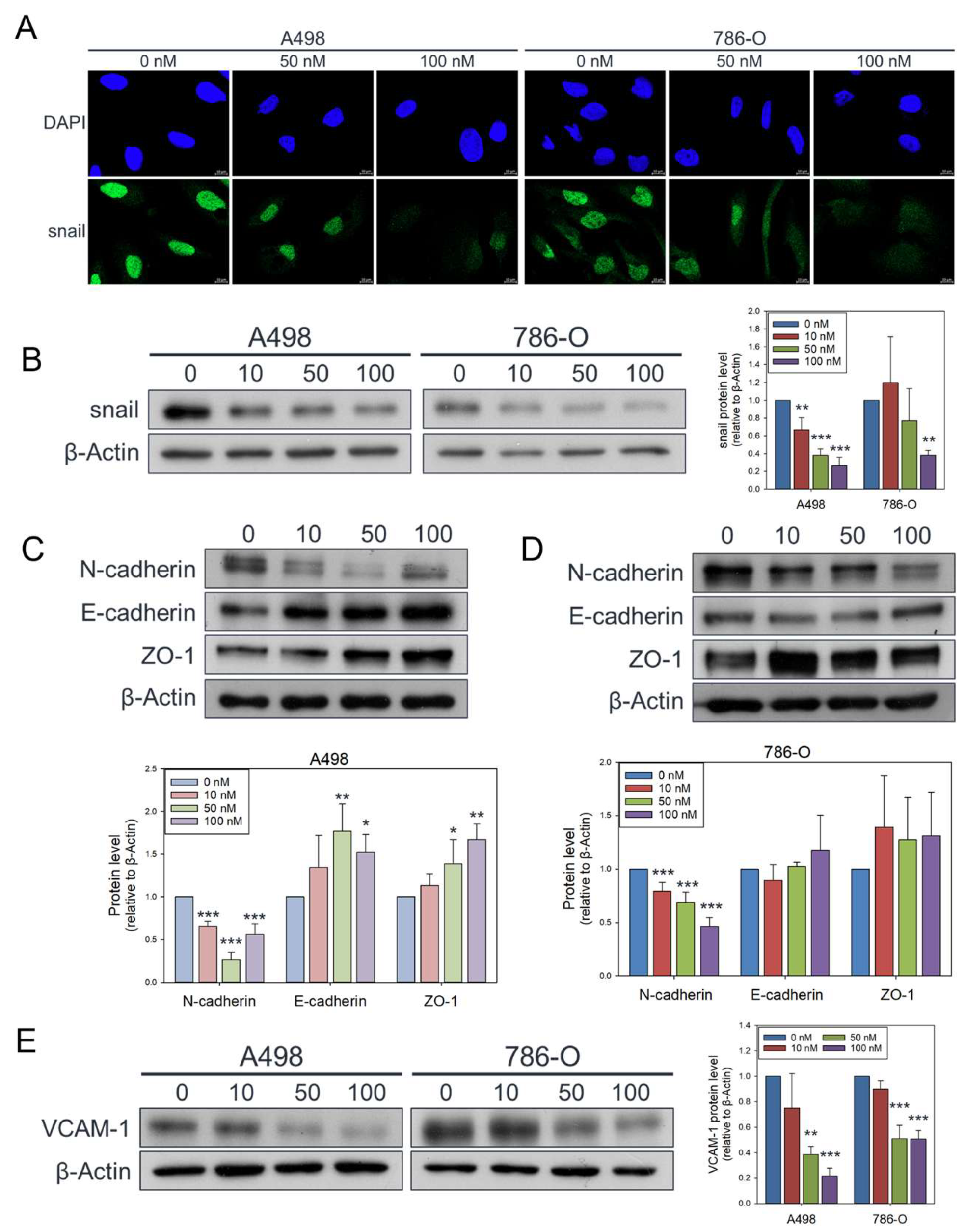

Figure 4.

Attenuated effects of olivomycin A on Snail, epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers, and VCAM-1 in renal cancer cells. (A) Confocal microscopy of nuclear Snail (green) and DAPI (blue) staining. Cells were treated with olivomycin A and a vehicle control and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis. Representative confocal images demonstrate reduced nuclear localization of Snail in olivomycin A–treated cells compared with controls. (B) Western blot analysis showing that olivomycin A markedly attenuated Snail protein expression in both A-498 and 786-O cells. (C) In A-498 cells, olivomycin A significantly reduced N-cadherin while upregulating E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression. (D) In 789-O cells, olivomycin A significantly downregulated N-cadherin and modestly increased E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression. (E) Olivomycin A also significantly reduced VCAM-1 expression in both A-498 and 798-O cells. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Quantitative data represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control).

Figure 4.

Attenuated effects of olivomycin A on Snail, epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers, and VCAM-1 in renal cancer cells. (A) Confocal microscopy of nuclear Snail (green) and DAPI (blue) staining. Cells were treated with olivomycin A and a vehicle control and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis. Representative confocal images demonstrate reduced nuclear localization of Snail in olivomycin A–treated cells compared with controls. (B) Western blot analysis showing that olivomycin A markedly attenuated Snail protein expression in both A-498 and 786-O cells. (C) In A-498 cells, olivomycin A significantly reduced N-cadherin while upregulating E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression. (D) In 789-O cells, olivomycin A significantly downregulated N-cadherin and modestly increased E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression. (E) Olivomycin A also significantly reduced VCAM-1 expression in both A-498 and 798-O cells. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Quantitative data represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control).

Figure 5.

Olivomycin A induces apoptosis in renal cancer cells. (A) Cells were treated with olivomycin A or vesicle control for 24 hours, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry. Results are presented as the percentage of apoptotic cells; values represented mean ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001 vs. controls). (B) Western blot analysis showing that olivomycin A markedly increased pro-apoptotic markers while reducing anti-apoptotic proteins in A-498 (top) and 786-O (bottom) cells. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Quantitative data represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control). (C) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), mitochondria (green), and cytochrome c (red) staining. Cells were treated with olivomycin A and a vehicle control and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis. Representative images show increased cytochrome c release from mitochondria into the cytoplasm in olivomycin A-treated cells compared with controls.

Figure 5.

Olivomycin A induces apoptosis in renal cancer cells. (A) Cells were treated with olivomycin A or vesicle control for 24 hours, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry. Results are presented as the percentage of apoptotic cells; values represented mean ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001 vs. controls). (B) Western blot analysis showing that olivomycin A markedly increased pro-apoptotic markers while reducing anti-apoptotic proteins in A-498 (top) and 786-O (bottom) cells. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Quantitative data represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control). (C) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), mitochondria (green), and cytochrome c (red) staining. Cells were treated with olivomycin A and a vehicle control and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis. Representative images show increased cytochrome c release from mitochondria into the cytoplasm in olivomycin A-treated cells compared with controls.

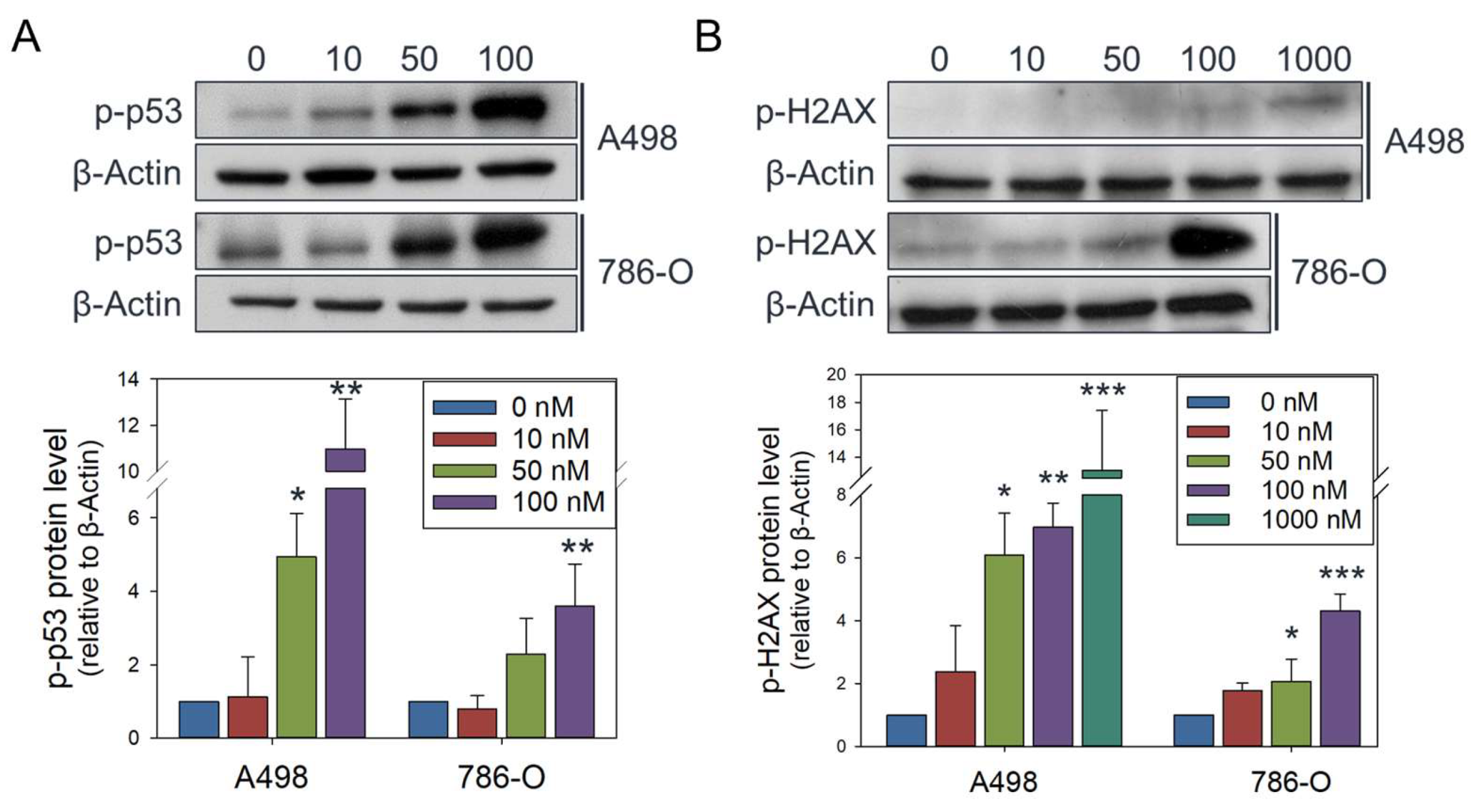

Figure 6.

Olivomycin A induces DNA damage signaling in renal cancer cells. (A, B) Western blot analysis showing that olivomycin A provoked expression of phosphorylated p53 (A) and H2AX (B). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed by the indicated antibodies, with β-actin used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Quantitative data represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control).

Figure 6.

Olivomycin A induces DNA damage signaling in renal cancer cells. (A, B) Western blot analysis showing that olivomycin A provoked expression of phosphorylated p53 (A) and H2AX (B). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed by the indicated antibodies, with β-actin used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Quantitative data represent means ± SE from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control).

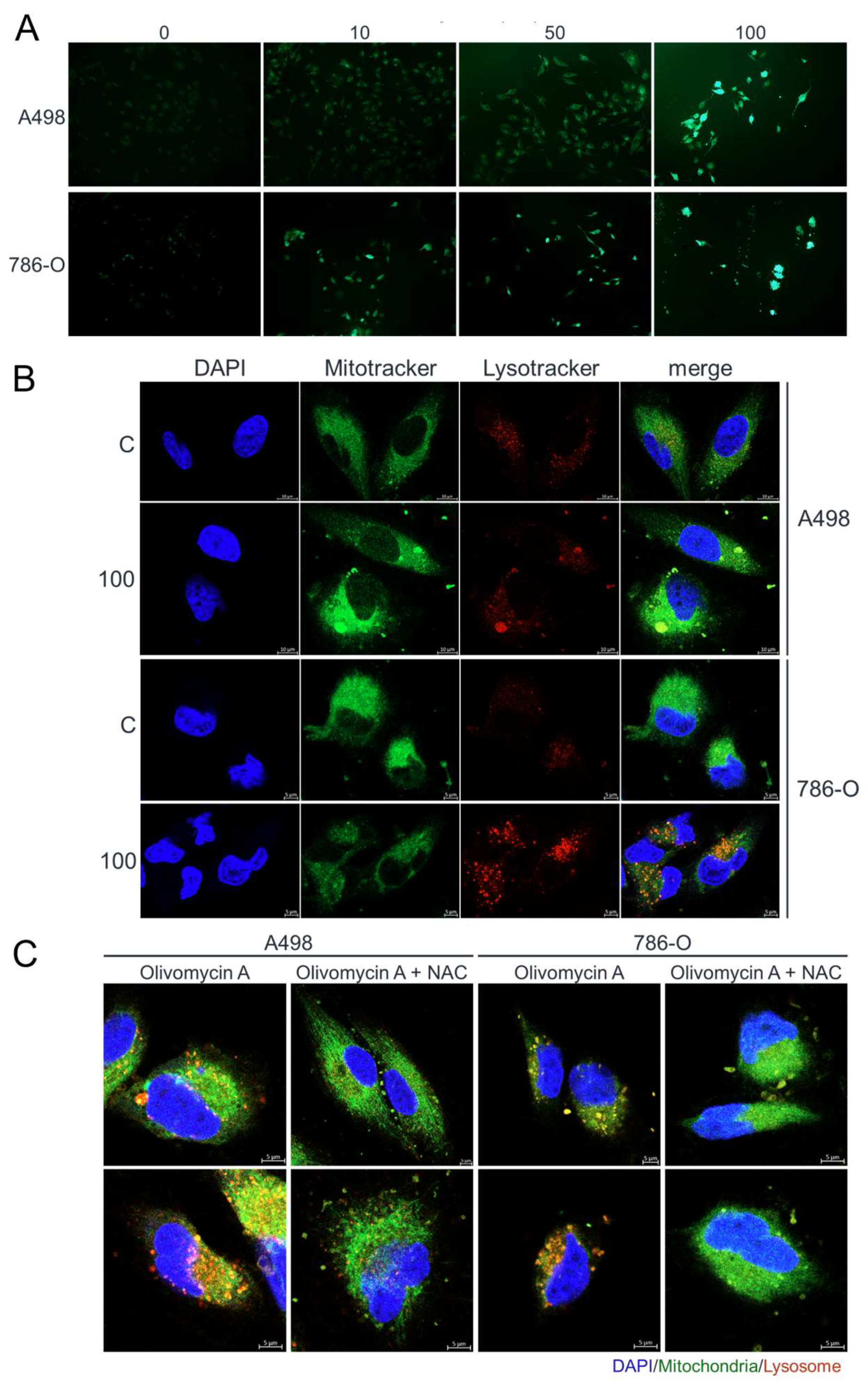

Figure 7.

Olivomycin A induces oxidative stress and lysosomal activity in renal cancer cells, effects reversed by NAC. (A) Fluorescent microscopy of DCFDA staining showing elevated ROS levels in cells treated with olivomycin A compared with vehicle control. (B) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and LysoTracker (red) staining showing that olivomycin A treatment increased lysosomal activity and mitochondrial stress in 786-O cells, but not in A486 cells, relative to controls. (C) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and LysoTracker (red) staining showing that NAC co-treatment attenuated olivomycin A-induced lysosomal activity and mitochondrial stress. Representative images are shown.

Figure 7.

Olivomycin A induces oxidative stress and lysosomal activity in renal cancer cells, effects reversed by NAC. (A) Fluorescent microscopy of DCFDA staining showing elevated ROS levels in cells treated with olivomycin A compared with vehicle control. (B) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and LysoTracker (red) staining showing that olivomycin A treatment increased lysosomal activity and mitochondrial stress in 786-O cells, but not in A486 cells, relative to controls. (C) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and LysoTracker (red) staining showing that NAC co-treatment attenuated olivomycin A-induced lysosomal activity and mitochondrial stress. Representative images are shown.

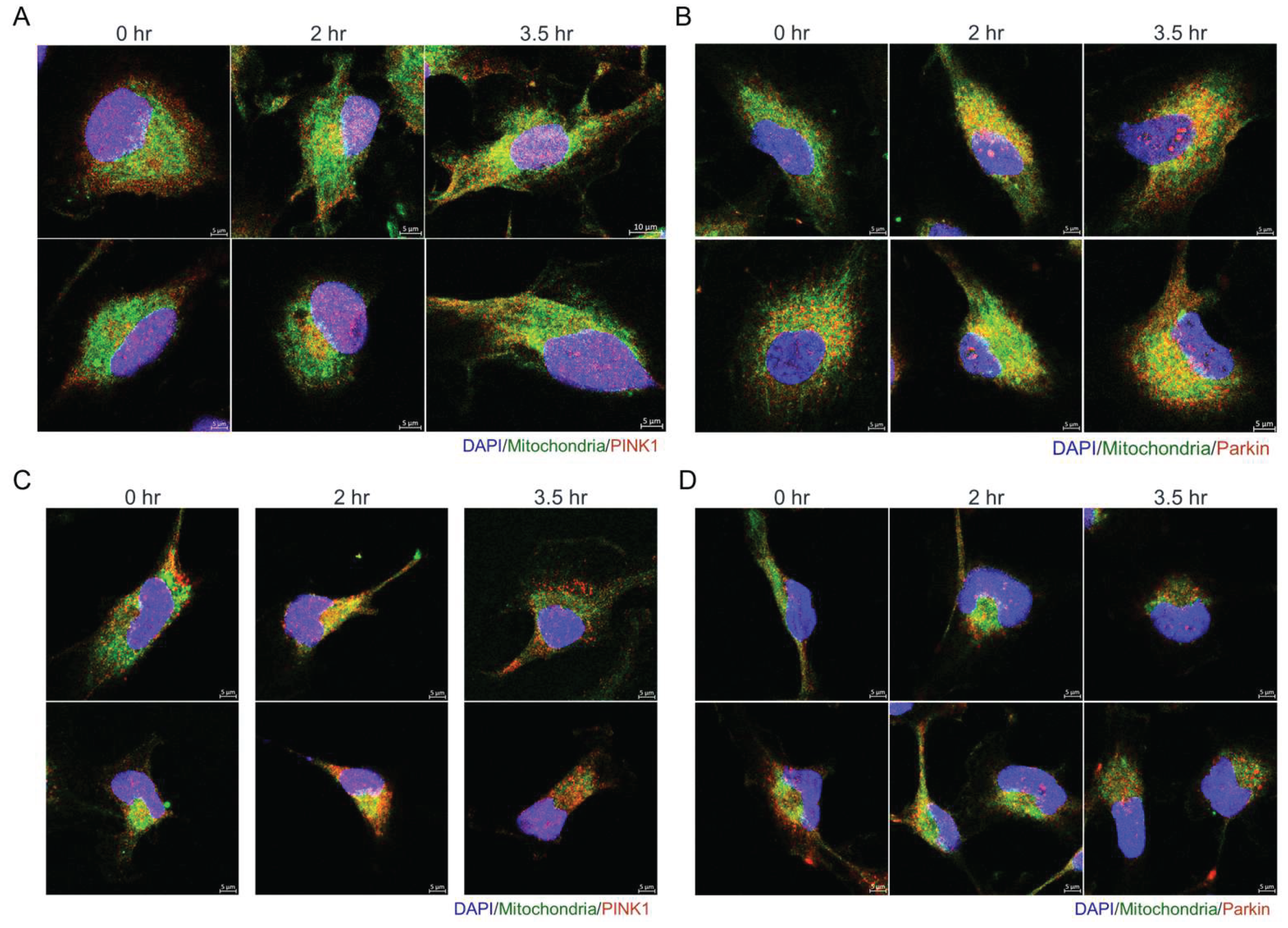

Figure 8.

Olivomycin A induces colocalization of mitochondria with PINK1 and Parkin in renal cancer cells. (A, C) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and PINK1 (red) staining showing that olivomycin A treatment increases the localization of PINK1 to mitochondria modestly in A-498 cells (A), and prominently in 786-O cells (C), relative to controls. (B, D) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and Parkin (red) staining showing that olivomycin A treatment increases the localization of Parkin to mitochondria in A-498 cells (B) but not in 786-O cells (D), relative to controls. Representative images are shown.

Figure 8.

Olivomycin A induces colocalization of mitochondria with PINK1 and Parkin in renal cancer cells. (A, C) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and PINK1 (red) staining showing that olivomycin A treatment increases the localization of PINK1 to mitochondria modestly in A-498 cells (A), and prominently in 786-O cells (C), relative to controls. (B, D) Confocal microscopy of DAPI (blue), MitoTracker (green), and Parkin (red) staining showing that olivomycin A treatment increases the localization of Parkin to mitochondria in A-498 cells (B) but not in 786-O cells (D), relative to controls. Representative images are shown.