Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

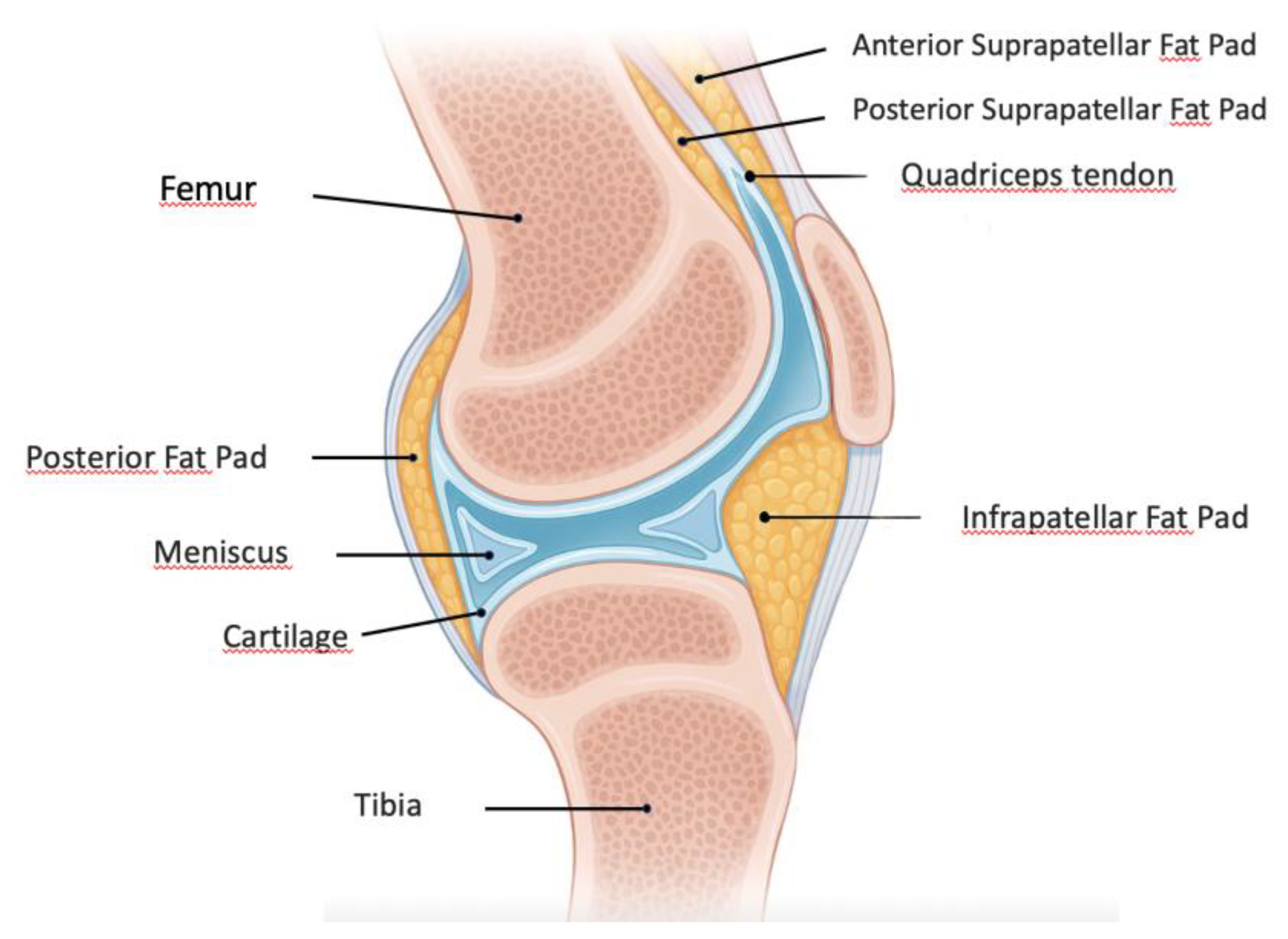

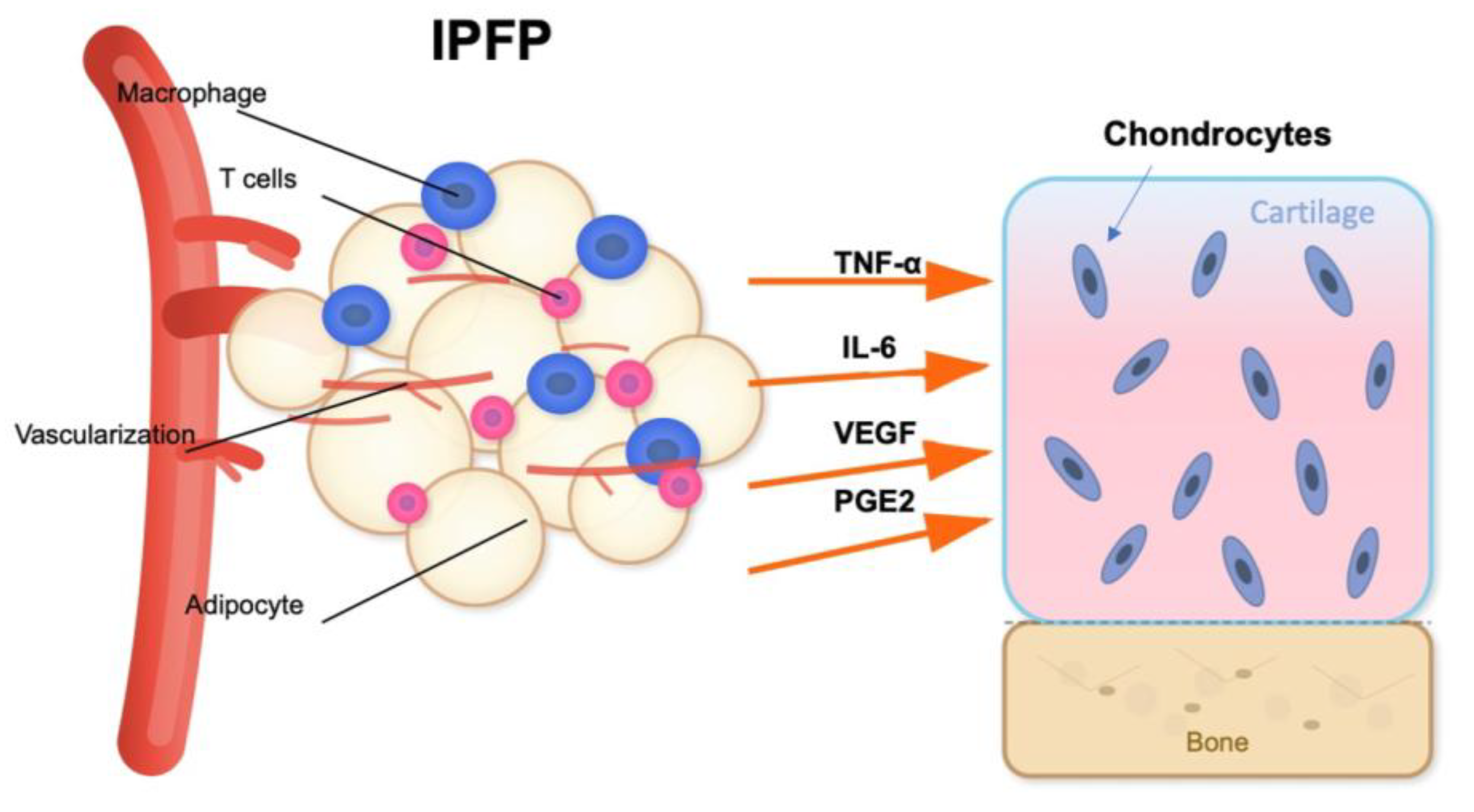

Pathophysiological Roles of the Infrapatellar Fat Pad in OA

2. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the Infrapatellar Fat Pad in Osteoarthritis

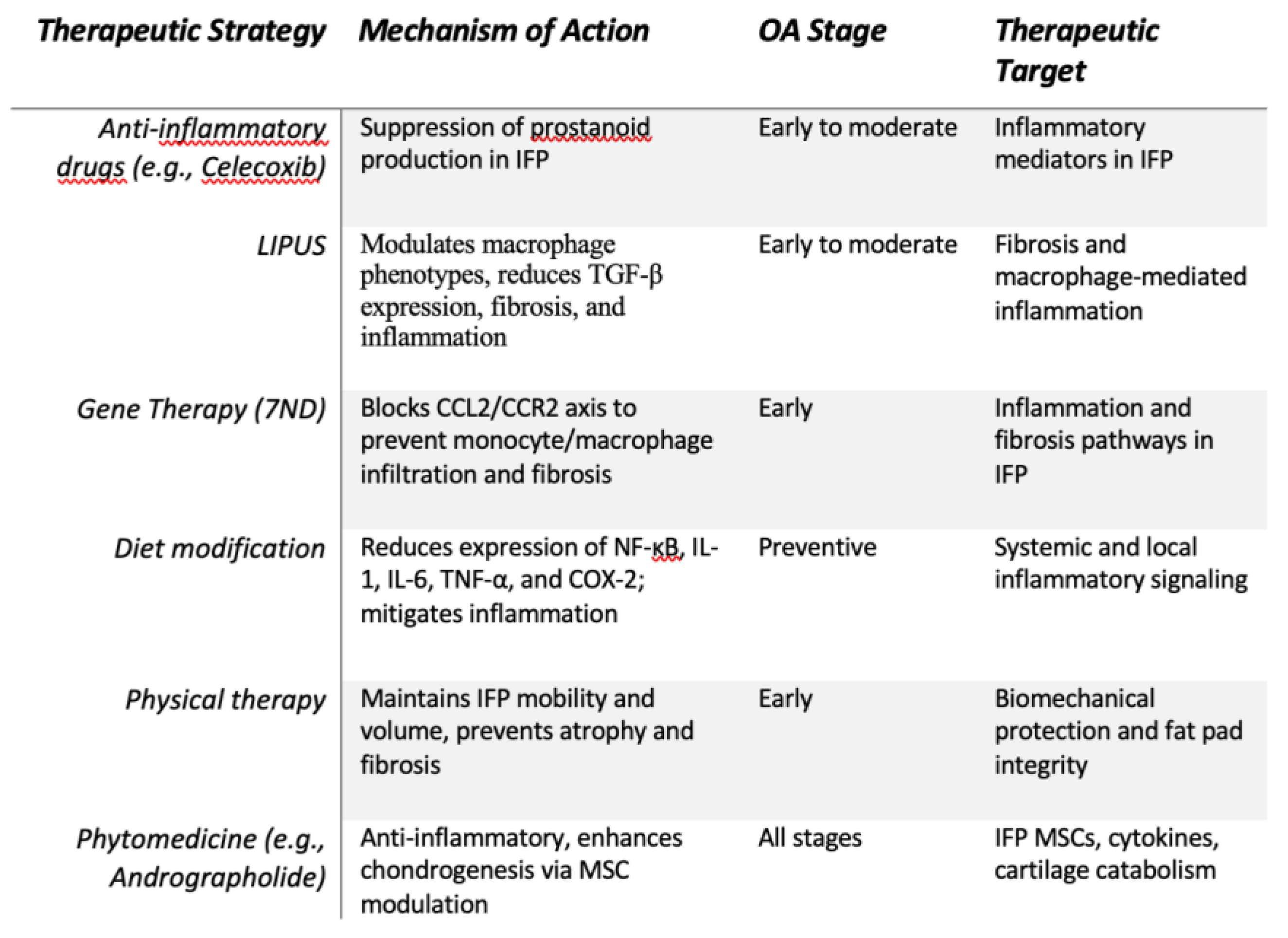

2.1. Conservative Therapies (Figure 3)

2.1.1. Anti-Inflammatory Agents

2.1.2. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound on the Fibrosis of the IFP

2.1.3. Gene therapy

2.1.4. Diet

2.1.5. Exercise

2.1.6. Phytomedicine

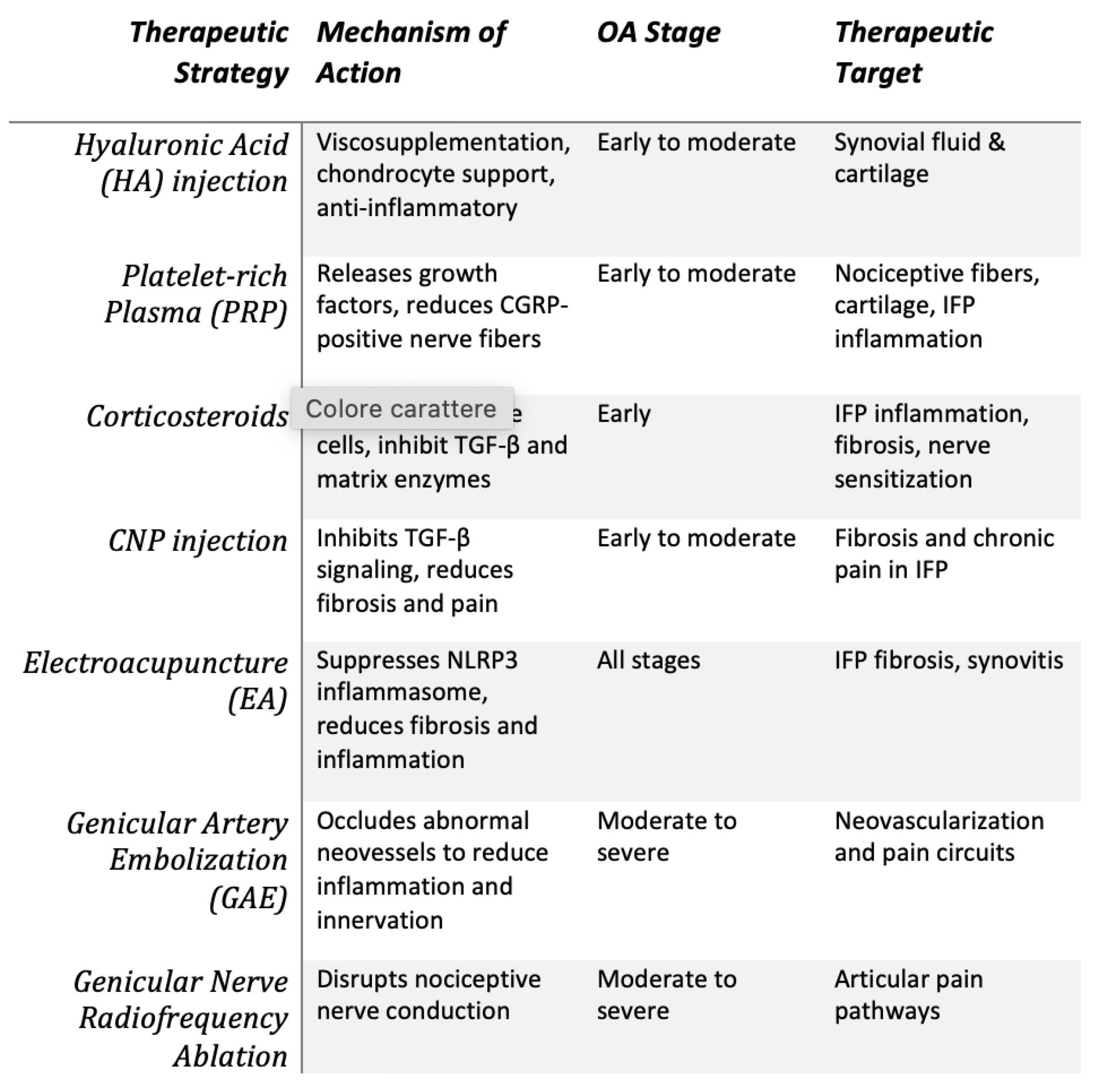

2.2. Minimally Invasive Treatments (Figure 4)

2.2.1. Intrarticular Injective Therapies

- Comparison between injective therapies

2.2.2. Electroacupuncture

2.2.3. Genicular Artery Embolization (GAE)

2.2.4. Genicular Nerve-targeted Cooled and Pulsed Radiofrequency Ablation

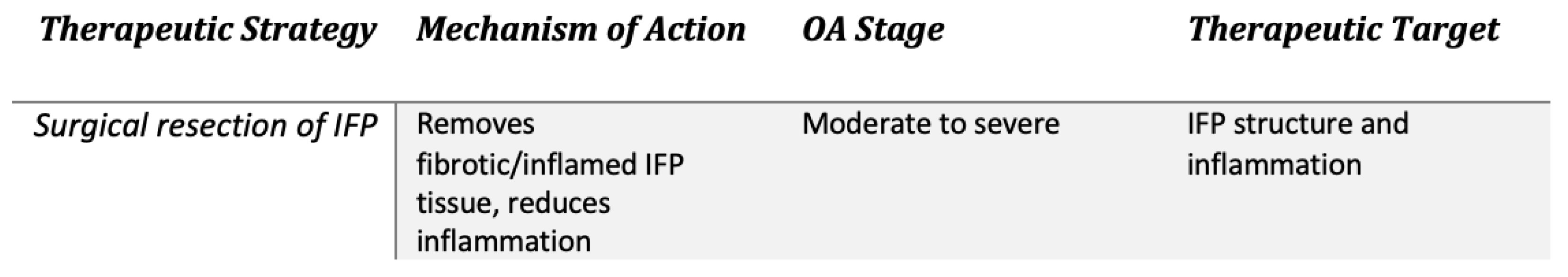

2.3. Surgery (Figure 5)

3. The Use of Infrapatellar Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Joint Cartilage Repair

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BMP-7 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein-7 |

| BMP-14 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein-14 |

| CCL2 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| CCR2 | C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2 |

| CCS | Corticosteroids |

| CNP | C-type natriuretic peptide |

| DAMPS | Damage Associated Molecular Patterns |

| EA | Electroacupuncture |

| GAE | Genicular Artery Embolization |

| GFs | Growth Factors |

| HA | Hyaluronic Acid |

| HIF-1 | Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 |

| IFP | Infrapatellar Fat Pad |

| IFPSCs | Infrapatellar Fat Pad-derived Stem Cells |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| KOA | Knee Osteoarthritis |

| LIPUS | Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| miR100-5p | MicroRNA 100-5-p |

| MSCIPFP-Exos | Mesenchymal-derived extracellular vesicles from the infrapatellar adipose tissue |

| MMP-1 | Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 |

| MMP-3 | Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 |

| MPA | Methylprednisolone acetate |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance |

| m-TOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PGF2α | Prostaglandin F2α |

| PGD2 | Prostaglandin D2 |

| PI3K/AKT | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/ Protein Kinase B. |

| PPAR-γ2 | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma 2 |

| PPTs | Pressure Pain Thresholds |

| PRP | Plateled Rich Plasma |

| RFA | Radiofrequency Ablation |

| RUNX2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| SASP | Secretory phenotype |

| SOX-9 | SRY-related HMG-box gene 9 |

| SMAD3 | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor—β |

| TIMP | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| VCAM1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| VEGF | Vascular endotelial growth factor |

| WOMAC | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index |

References

- Steinmetz JD, Culbreth GT, Haile LM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(9):e508-e522. [CrossRef]

- OARSI (Osteoathritis Research Society International). https://oarsi.org/research/standardization-osteoarthritis-definitions.

- Tang S, Zhang C, Oo WM, et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;11(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Knights AJ, Redding SJ, Maerz T. Inflammation in osteoarthritis: the latest progress and ongoing challenges. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023;35(2):128-134. [CrossRef]

- Goldring MB, Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(5):471-478. [CrossRef]

- Chen D, Shen J, Zhao W, et al. Osteoarthritis: toward a comprehensive understanding of pathological mechanism. Bone Res. 2017;5(1):16044. [CrossRef]

- Mathiessen A, Conaghan PG. Synovitis in osteoarthritis: current understanding with therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):18. [CrossRef]

- Kloppenburg M, Namane M, Cicuttini F. Osteoarthritis. The Lancet. 2025;405(10472):71-85. [CrossRef]

- Wei Y, Bai L. Recent advances in the understanding of molecular mechanisms of cartilage degeneration, synovitis and subchondral bone changes in osteoarthritis. Connect Tissue Res. 2016;57(4):245-261. [CrossRef]

- Coaccioli S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Zis P, Rinonapoli G, Varrassi G. Osteoarthritis: New Insight on Its Pathophysiology. J Clin Med. 2022;11(20):6013. [CrossRef]

- Binvignat M, Sellam J, Berenbaum F, Felson DT. The role of obesity and adipose tissue dysfunction in osteoarthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024;20(9):565-584. [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Linares N, Eymard F, Berenbaum F, Houard X. Role of adipose tissues in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2021;33(1):84-93. [CrossRef]

- Coelho M, Oliveira T, Fernandes R. State of the art paper Biochemistry of adipose tissue: an endocrine organ. Archives of Medical Science. 2013;2:191-200. [CrossRef]

- Trayhurn P, Drevon CA, Eckel J. Secreted proteins from adipose tissue and skeletal muscle – adipokines, myokines and adipose/muscle cross-talk. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2011;117(2):47-56. [CrossRef]

- Neumann E, Junker S, Schett G, Frommer K, Müller-Ladner U. Adipokines in bone disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(5):296-302. [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Yano S, Yamauchi M, Yamamoto M, Sugimoto T. Adiponectin and AMP kinase activator stimulate proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Lin YY, Chen CY, Chuang TY, et al. Adiponectin receptor 1 regulates bone formation and osteoblast differentiation by GSK-3β/β-Catenin signaling in mice. Bone. 2014;64:147-154. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi SM, Saniee N, Borzoo T, Radmanesh E. Osteoporosis and Leptin: A Systematic Review. Iran J Public Health. Published online January 15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cheleschi S, Gallo I, Barbarino M, et al. MicroRNA Mediate Visfatin and Resistin Induction of Oxidative Stress in Human Osteoarthritic Synovial Fibroblasts Via NF-κB Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20):5200. [CrossRef]

- Economou A, Mallia I, Fioravanti A, et al. The Role of Adipokines between Genders in the Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(19):10865. [CrossRef]

- Cheleschi S, Tenti S, Barbarino M, et al. Exploring the Crosstalk between Hydrostatic Pressure and Adipokines: An In Vitro Study on Human Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):2745. [CrossRef]

- Klein-Wieringa IR, Kloppenburg M, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, et al. The infrapatellar fat pad of patients with osteoarthritis has an inflammatory phenotype. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):851-857. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Lin Y, Yan CH, Zhang W. Adipokine Signaling Pathways in Osteoarthritis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- de Boer TN, van Spil WE, Huisman AM, et al. Serum adipokines in osteoarthritis; comparison with controls and relationship with local parameters of synovial inflammation and cartilage damage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(8):846-853. [CrossRef]

- Bas S, Finckh A, Puskas GJ, et al. Adipokines correlate with pain in lower limb osteoarthritis: different associations in hip and knee. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2577-2583. [CrossRef]

- Tu C, He J, Wu B, Wang W, Li Z. An extensive review regarding the adipokines in the pathogenesis and progression of osteoarthritis. Cytokine. 2019;113:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, He C. Pro-inflammatory cytokines: The link between obesity and osteoarthritis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018;44:38-50. [CrossRef]

- Clockaerts S, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Runhaar J, et al. The infrapatellar fat pad should be considered as an active osteoarthritic joint tissue: a narrative review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(7):876-882. [CrossRef]

- Wang MG, Seale P, Furman D. The infrapatellar fat pad in inflammaging, knee joint health, and osteoarthritis. npj Aging. 2024;10(1):34. [CrossRef]

- Yue S, Zhai G, Zhao S, et al. The biphasic role of the infrapatellar fat pad in osteoarthritis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2024;179:117364. [CrossRef]

- Frasca D, Blomberg BB. Adipose tissue, immune aging, and cellular senescence. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(5):573-587. [CrossRef]

- Jeon OH, David N, Campisi J, Elisseeff JH. Senescent cells and osteoarthritis: a painful connection. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2018;128(4):1229-1237. [CrossRef]

- Bolia IK, Mertz K, Faye E, et al. Cross-Communication Between Knee Osteoarthritis and Fibrosis: Molecular Pathways and Key Molecules. Open Access J Sports Med. 2022;Volume 13:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Hengtrakool P, Leearamwat N, Sengprasert P, et al. Infrapatellar fat pad adipose tissue-derived macrophages display a predominant CD11c+CD206+ phenotype and express genotypes attributable to key features of OA pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Fontanella CG, Belluzzi E, Pozzuoli A, et al. Mechanical behavior of infrapatellar fat pad of patients affected by osteoarthritis. J Biomech. 2022;131:110931. [CrossRef]

- Inomata K, Tsuji K, Onuma H, et al. Time course analyses of structural changes in the infrapatellar fat pad and synovial membrane during inflammation-induced persistent pain development in rat knee joint. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Leese J, Davies DC. An investigation of the anatomy of the infrapatellar fat pad and its possible involvement in anterior pain syndrome: a cadaveric study. J Anat. 2020;237(1):20-28. [CrossRef]

- Walsh DA, Mapp PI, Kelly S. Calcitonin gene-related peptide in the joint: contributions to pain and inflammation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(5):965-978. [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack M, Meier F, Walter GF, et al. Distribution of substance-P nerves inside the infrapatellar fat pad and the adjacent synovial tissue: a neurohistological approach to anterior knee pain syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125(9):592-597. [CrossRef]

- Onuma H, Tsuji K, Hoshino T, et al. Fibrotic changes in the infrapatellar fat pad induce new vessel formation and sensory nerve fiber endings that associate prolonged pain. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2020;38(6):1296-1306. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa J, Uchida K, Takano S, et al. Expression of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis patients. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):65. [CrossRef]

- Neogi T, Guermazi A, Roemer F, et al. Association of Joint Inflammation With Pain Sensitization in Knee Osteoarthritis: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2016;68(3):654-661. [CrossRef]

- Scanzello CR, Goldring SR. The role of synovitis in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Bone. 2012;51(2):249-257. [CrossRef]

- Schaible HG. Nociceptive neurons detect cytokines in arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(5):470. [CrossRef]

- Zou Y, Liu C, Wang Z, Li G, Xiao J. Neural and immune roles in osteoarthritis pain: Mechanisms and intervention strategies. J Orthop Translat. 2024;48:123-132. [CrossRef]

- Timur UT, Caron MMJ, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, et al. Celecoxib-mediated reduction of prostanoid release in Hoffa’s fat pad from donors with cartilage pathology results in an attenuated inflammatory phenotype. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(5):697-706. [CrossRef]

- ter Haar G. Therapeutic ultrasound. European Journal of Ultrasound. 1999;9(1):3-9. [CrossRef]

- Kitano M, Kawahata H, Okawa Y, et al. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on the infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Phys Ther Sci. 2023;35(3):2022-2085. [CrossRef]

- Feltham T, Paudel S, Lobao M, Schon L, Zhang Z. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Suppresses Synovial Macrophage Infiltration and Inflammation in Injured Knees in Rats. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47(4):1045-1053. [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa T, Kawahata H, Kudo S. Effect of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound on Macrophage Properties and Fibrosis in the Infrapatellar Fat Pad in a Carrageenan-Induced Knee Osteoarthritis Rat Model. Cureus. Published online April 29, 2024. [CrossRef]

- He S, Fan C, Ji Y, et al. SENP3 facilitates M1 macrophage polarization via the HIF-1α/PKM2 axis in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Innate Immun. 2023;29(1-2):25-34. [CrossRef]

- Gouda SAA, Aboulhoda BE, Abdelwahed OM, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) switched macrophage into M2 phenotype and mitigated necroptosis and increased HSP 70 in gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity. Life Sci. 2023;314:121338. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura T, Fujihara S, Yamamoto-Nagata K, Katsura T, Inubushi T, Tanaka E. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Reduces the Inflammatory Activity of Synovitis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39(12):2964-2971. [CrossRef]

- Qin H, Luo Z, Sun Y, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes skeletal muscle regeneration via modulating the inflammatory immune microenvironment. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(4):1123-1145. [CrossRef]

- Gurkan I, Ranganathan A, Yang X, et al. Modification of osteoarthritis in the guinea pig with pulsed low-intensity ultrasound treatment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(5):724-733. [CrossRef]

- Liao B, Guan M, Tan Q, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound inhibits fibroblast-like synoviocyte proliferation and reduces synovial fibrosis by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J Orthop Translat. 2021;30:41-50. [CrossRef]

- Yi X, Wu L, Liu J, Qin Y, Li B, Zhou Q. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound protects subchondral bone in rabbit temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis by suppressing TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2020;38(11):2505-2512. [CrossRef]

- Tacke F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66(6):1300-1312. [CrossRef]

- Mansour SG, Puthumana J, Coca SG, Gentry M, Parikh CR. Biomarkers for the detection of renal fibrosis and prediction of renal outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):72. [CrossRef]

- Distler JHW, Akhmetshina A, Schett G, Distler O. Monocyte chemoattractant proteins in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology. 2009;48(2):98-103. [CrossRef]

- Yuan GH, Masuko-Hongo K, Sakata M, et al. The role of C-C chemokines and their receptors in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(5):1056-1070. [CrossRef]

- Miller RE, Malfait AM. Can we target CCR2 to treat osteoarthritis? The trick is in the timing! Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(6):799-801. [CrossRef]

- Miotla Zarebska J, Chanalaris A, Driscoll C, et al. CCL2 and CCR2 regulate pain-related behaviour and early gene expression in post-traumatic murine osteoarthritis but contribute little to chondropathy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(3):406-412. [CrossRef]

- Favero M, El-Hadi H, Belluzzi E, et al. Infrapatellar fat pad features in osteoarthritis: a histopathological and molecular study. Rheumatology. 2017;56(10):1784-1793. [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Wei W, Feijt C, et al. Stimulation of Fibrotic Processes by the Infrapatellar Fat Pad in Cultured Synoviocytes From Patients With Osteoarthritis: A Possible Role for Prostaglandin F 2α. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(8):2070-2080. [CrossRef]

- Longobardi L, Jordan JM, Shi XA, et al. Associations between the chemokine biomarker CCL2 and knee osteoarthritis outcomes: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(9):1257-1261. [CrossRef]

- Morrison NA, Day CJ, Nicholson GC. Dominant Negative <scp>MCP</scp> -1 Blocks Human Osteoclast Differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(2):303-312. [CrossRef]

- Yao Z, Keeney M, Lin T, et al. Mutant monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 protein attenuates migration of and inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages exposed to orthopedic implant wear particles. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(9):3291-3297. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura H, Nakagawa Y, Muneta T, Koga H. A CCL2/MCP-1 antagonist attenuates fibrosis of the infrapatellar fat pad in a rat model of arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):674. [CrossRef]

- Barboza E, Hudson J, Chang W, et al. Profibrotic Infrapatellar Fat Pad Remodeling Without M1 Macrophage Polarization Precedes Knee Osteoarthritis in Mice With Diet-Induced Obesity. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2017;69(6):1221-1232. [CrossRef]

- Iwata M, Ochi H, Hara Y, et al. Initial Responses of Articular Tissues in a Murine High-Fat Diet-Induced Osteoarthritis Model: Pivotal Role of the IPFP as a Cytokine Fountain. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60706. [CrossRef]

- Chang W, DeMoe J, Kent C, et al. 130 INFRAPATELLAR FAT PAD HYPERTROPHY WITHOUT INFLAMMATION IN A DIET-INDUCED MOUSE MODEL OF OBESHY AND OSTEOARTHRITIS. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:S66. [CrossRef]

- Han W, Cai S, Liu Z, et al. Infrapatellar fat pad in the knee: is local fat good or bad for knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(4):R145. [CrossRef]

- Chuckpaiwong B, Charles HC, Kraus VB, Guilak F, Nunley JA. Age-associated increases in the size of the infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis as measured by 3T MRI. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2010;28(9):1149-1154. [CrossRef]

- Diepold J, Ruhdorfer A, Dannhauer T, Wirth W, Steidle E, Eckstein F. Sex-differences of the healthy infra-patellar (Hoffa) fat pad in relation to intermuscular and subcutaneous fat content – Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2015;200:30-36. [CrossRef]

- Cortez M, Carmo LS, Rogero MM, Borelli P, Fock RA. A High-Fat Diet Increases IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α Production by Increasing NF-κB and Attenuating PPAR-γ Expression in Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Inflammation. 2013;36(2):379-386. [CrossRef]

- Radakovich LB, Marolf AJ, Culver LA, Santangelo KS. Calorie restriction with regular chow, but not a high-fat diet, delays onset of spontaneous osteoarthritis in the Hartley guinea pig model. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):145. [CrossRef]

- Hannon J, Bardenett S, Singleton S, Garrison JC. Evaluation, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Implications of the Infrapatellar Fat Pad. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2016;8(2):167-171. [CrossRef]

- Guilak F, Fermor B, Keefe FJ, et al. The Role of Biomechanics and Inflammation in Cartilage Injury and Repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:17-26. [CrossRef]

- Teichtahl AJ, Wulidasari E, Brady SRE, et al. A large infrapatellar fat pad protects against knee pain and lateral tibial cartilage volume loss. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):318. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi I, Matsuzaki T, Kuroki H, Hoso M. Disuse histological changes of an unloading environment on joint components in rat knee joints. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2019;1(1-2):100008. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe M, Hoso M, Hibino I, Matsuzaki T, Kojima S. Histopathological Changes of Joint Capsule after Joint Immobility Compared with Aging in Rats. J Phys Ther Sci. 2010;22(4):369-374. [CrossRef]

- Trudel G, Uhthoff HK, Goudreau L, Laneuville O. Quantitative analysis of the reversibility of knee flexion contractures with time: an experimental study using the rat model. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15(1):338. [CrossRef]

- Takeda K, Takeshima E, Kojima S, Watanabe M, Matsuzaki T, Hoso M. Daily and short-term application of joint movement for the prevention of infrapatellar fat pad atrophy due to immobilization. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019;31(11):873-877. [CrossRef]

- Park J, Lee SW. Medical treatment of osteoarthritis: botanical pharmacologic aspect. Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2024;31(2):68-78. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Efferth T, Hua X, Zhang X an. Medicinal plants and their secondary metabolites in alleviating knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Phytomedicine. 2022;105:154347. [CrossRef]

- Ding Q hai, Ji X wei, Cheng Y, Yu Y quan, Qi Y ying, Wang X hua. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases and inducible nitric oxide synthase by andrographolide in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(6):1124-1132. [CrossRef]

- Kulsirirat T, Honsawek S, Takeda-Morishita M, et al. The Effects of Andrographolide on the Enhancement of Chondrogenesis and Osteogenesis in Human Suprapatellar Fat Pad Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Molecules. 2021;26(7):1831. [CrossRef]

- Atul Bhattaram V, Graefe U, Kohlert C, Veit M, Derendorf H. Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability of Herbal Medicinal Products. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:1-33. [CrossRef]

- Anil U, Markus DH, Hurley ET, et al. The efficacy of intra-articular injections in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Knee. 2021;32:173-182. [CrossRef]

- Komatsu S, Iwata H, Nabeshima T. Studies on the Kinetics, Metabolism and Re-utilisation after Intra-articular Administration of Hyaluronan to Rabbits. Arzneimittelforschung. 2011;49(05):427-433. [CrossRef]

- Lee CL, Wang YC, Huang HT, Chen CH, Chang KL, Tien YC. Efficacy of Intra-Articular Injection of Biofermentation-Derived High-Molecular Hyaluronic Acid in Knee Osteoarthritis: An Ultrasonographic Study. Cartilage. 2022;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Qu Z, Koga H, Tsuji K, et al. Hyaluronic acid sheet transplantation attenuates infrapatellar fat pad fibrosis and pain in a rat arthritis model. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2023;41(11):2442-2454. [CrossRef]

- Chen WH, Lin CM, Huang CF, et al. Functional Recovery in Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes Through Hyaluronic Acid and Platelet-Rich Plasma–Inhibited Infrapatellar Fat Pad Adipocytes. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2696-2705. [CrossRef]

- Filardo G, Kon E, Buda R, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular knee injections for the treatment of degenerative cartilage lesions and osteoarthritis. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2011;19(4):528-535. [CrossRef]

- Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Karas V, et al. The Anti-inflammatory and Matrix Restorative Mechanisms of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(1):35-41. [CrossRef]

- Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Karas V, et al. The Anti-inflammatory and Matrix Restorative Mechanisms of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(1):35-41. [CrossRef]

- Araya N, Miyatake K, Tsuji K, et al. Intra-articular Injection of Pure Platelet-Rich Plasma Is the Most Effective Treatment for Joint Pain by Modulating Synovial Inflammation and Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Expression in a Rat Arthritis Model. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(8):2004-2012. [CrossRef]

- Burchard R, Huflage H, Soost C, Richter O, Bouillon B, Graw JA. Efficiency of platelet-rich plasma therapy in knee osteoarthritis does not depend on level of cartilage damage. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):153. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Chen X, Zhang H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma relieves inflammation and pain by regulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization in knee osteoarthritis rats. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12805. [CrossRef]

- Yan X, Ye Y, Wang L, Xue J, Shen N, Li T. Platelet-rich plasma alleviates neuropathic pain in osteoarthritis by downregulating microglial activation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):331. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Tolmeijer S, Oskam JM, Tonkens T, Meijer AH, Schaaf MJM. Glucocorticoids inhibit macrophage differentiation towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype upon wounding without affecting their migration. Dis Model Mech. 2019;12(5). [CrossRef]

- Lee MJ, Pramyothin P, Karastergiou K, Fried SK. Deconstructing the roles of glucocorticoids in adipose tissue biology and the development of central obesity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2014;1842(3):473-481. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen TS, Graven-Nielsen T, Ellegaard K, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Bliddal H, Henriksen M. Intra-Articular Analgesia and Steroid Reduce Pain Sensitivity in Knee OA Patients: An Interventional Cohort Study. Pain Res Treat. 2014;2014:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Bensa A, Salerno M, Boffa A, et al. Corticosteroid injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis present a wide spectrum of effects ranging from detrimental to disease-modifying: A systematic review of preclinical evidence by the ESSKA Orthobiologic Initiative. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2024;32(11):2725-2745. [CrossRef]

- Wen FQ, Kohyama T, Sköld CM, et al. Glucocorticoids Modulate TGF-β Production by Human Fetal Lung Fibroblasts. Inflammation. 2003;27(1):9-19. [CrossRef]

- Wen FQ, Kohyama T, Sköld CM, et al. Glucocorticoids Modulate TGF-β Production. Inflammation. 2002;26(6):279-290. [CrossRef]

- Lopes EBP, Filiberti A, Husain SA, Humphrey MB. Immune Contributions to Osteoarthritis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2017;15(6):593-600. [CrossRef]

- Heard BJ, Solbak NM, Chung M, et al. The infrapatellar fat pad is affected by injury induced inflammation in the rabbit knee: use of dexamethasone to mitigate damage. Inflammation Research. 2016;65(6):459-470. [CrossRef]

- Barton KI, Chung M, Frank CB, Shrive NG, Hart DA. Methylprednisolone acetate mitigates IL1β induced changes in matrix metalloproteinase gene expression in skeletally immature ovine explant knee tissues. Inflammation Research. 2021;70(1):99-107. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ruan G, Zheng P, et al. Efficacy and safety of GLucocorticoid injections into InfrapaTellar faT pad in patients with knee ostEoarthRitiS: a randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2025;33:S223. [CrossRef]

- Soeki T, Kishimoto I, Okumura H, et al. C-type natriuretic peptide, a novel antifibrotic and antihypertrophic agent, prevents cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(4):608-616. [CrossRef]

- Kimura T, Nojiri T, Hino J, et al. C-type natriuretic peptide ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by acting on lung fibroblasts in mice. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):19. [CrossRef]

- An JS, Tsuji K, Onuma H, et al. Inhibition of fibrotic changes in infrapatellar fat pad alleviates persistent pain and articular cartilage degeneration in monoiodoacetic acid-induced rat arthritis model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;29(3):380-388. [CrossRef]

- Gupta N, Khatri K, Lakhani A, et al. Long-term effectiveness of intra-articular injectables in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):227. [CrossRef]

- José F.S.D. Lana AWSESEFVSCHCVSMAAHVAUPCMKOJMABMHASWDB. Randomized controlled trial comparing hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma and the combination of both in the treatment of mild and moderate osteoarthritis of the knee. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2016;12(2):69-78. [CrossRef]

- Anil U, Markus DH, Hurley ET, et al. The efficacy of intra-articular injections in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Knee. 2021;32:173-182. [CrossRef]

- He W wei, Kuang M jie, Zhao J, et al. Efficacy and safety of intraarticular hyaluronic acid and corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery. 2017;39:95-103. [CrossRef]

- Qiao X, Yan L, Feng Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, and PRP and combination therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):926. [CrossRef]

- Jones A, Doherty M. Intra-articular corticosteroids are effective in osteoarthritis but there are no clinical predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(11):829-832. [CrossRef]

- Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson DT. Intra-articular Hyaluronic Acid in Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2003;290(23):3115. [CrossRef]

- Jameson C. Autologous Platelet Concentrate for the Production of Platelet Gel. Lab Med. 2007;38(1):39-42. [CrossRef]

- Liu CY, Tu JF, Lee MS, et al. Is acupuncture effective for knee osteoarthritis? A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e052270. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Zhang L, Yang S, Wen B, Chen J, Chang J. Electroacupuncture ameliorates knee osteoarthritis in rats via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and reducing pyroptosis. Mol Pain. 2023;19. [CrossRef]

- Nemschak G, Pretterklieber ML. The Patellar Arterial Supply via the Infrapatellar Fat Pad (of Hoffa): A Combined Anatomical and Angiographical Analysis. Anat Res Int. 2012;2012:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kohn D, Deiler S, Rudert M. Arterial blood supply of the infrapatellar fat pad. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1995;114(2):72-75. [CrossRef]

- Taslakian B, Miller LE, Mabud TS, et al. Genicular artery embolization for treatment of knee osteoarthritis pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2023;5(2):100342. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien S, Blakeney WG, Soares J. Selective Genicular Artery Embolization in the Management of Osteoarthritic Knee Pain—A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(11):3256. [CrossRef]

- Abussa R, Jeremic A. Bridging the Gap between Injections and Surgery: Meta-Analysis of Genicular Artery Embolization in Knee Osteoarthritis. Acad Radiol. Published online May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf N, Tahir MJ, Arabi TZ, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Genicular Artery Embolization for Knee Joint Osteoarthritis Associated Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. Published online April 11, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Choi WJ, Hwang SJ, Song JG, et al. Radiofrequency treatment relieves chronic knee osteoarthritis pain: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2011;152(3):481-487. [CrossRef]

- Fonkoué L, Behets C, Kouassi JÉK, et al. Distribution of sensory nerves supplying the knee joint capsule and implications for genicular blockade and radiofrequency ablation: an anatomical study. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 2019;41(12):1461-1471. [CrossRef]

- Chou SH, Shen PC, Lu CC, et al. Comparison of Efficacy among Three Radiofrequency Ablation Techniques for Treating Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7424. [CrossRef]

- Hong T, Wang H, Li G, Yao P, Ding Y. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 12 Randomized Controlled Trials Evaluating the Efficacy of Invasive Radiofrequency Treatment for Knee Pain and Function. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1-14. [CrossRef]

- Karaman H, Tüfek A, Kavak GÖ, et al. Intra-articularly applied pulsed radiofrequency can reduce chronic knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2011;74(8):336-340. [CrossRef]

- Menzies RD, Hawkins JK. Analgesia and Improved Performance in a Patient Treated by Cooled Radiofrequency for Pain and Dysfunction Postbilateral Total Knee Replacement. Pain Practice. 2015;15(6). [CrossRef]

- Soetjahjo B, Adriansyah D, Yudistira MB, Rahman AN, Herman H, Diwan S. Systematic Review The Analgesic Effectiveness of Genicular Nerve-targeted Cooled and Pulsed Radiofrequency Ablation for Osteoarthritis Knee Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. www.painphysicianjournal.com.

- Stephen JM, Sopher R, Tullie S, Amis AA, Ball S, Williams A. The infrapatellar fat pad is a dynamic and mobile structure, which deforms during knee motion, and has proximal extensions which wrap around the patella. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2018;26(11):3515-3524. [CrossRef]

- Ali MM, Phillips SA, Mahmoud AM. HIF1α/TET1 Pathway Mediates Hypoxia-Induced Adipocytokine Promoter Hypomethylation in Human Adipocytes. Cells. 2020;9(1):134. [CrossRef]

- Macchi V, Porzionato A, Sarasin G, et al. The Infrapatellar Adipose Body: A Histotopographic Study. Cells Tissues Organs. 2016;201(3):220-231. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Gao Q. Partial excision of infrapatellar fat pad for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19(1):631. [CrossRef]

- Afzali MF, Radakovich LB, Sykes MM, et al. Early removal of the infrapatellar fat pad/synovium complex beneficially alters the pathogenesis of moderate stage idiopathic knee osteoarthritis in male Dunkin Hartley guinea pigs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):282. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Lu P, Yao H, et al. Observation of the Effects of Infrapatellar Fat Pad Excision on the Inflammatory Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis in Mice. J Inflamm Res. 2025;Volume 18:6653-6672. [CrossRef]

- Yao B, Samuel LT, Acuña AJ, et al. Infrapatellar Fat Pad Resection or Preservation during Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. J Knee Surg. 2021;34(04):415-421. [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari A, Banskota B, Bhusal R, Banskota AK. Effect of Infrapatellar Fat Pad Preservation vs Resection on Clinical Outcomes After Total Knee Arthroplasty in Patient with End-Stage Osteoarthritis. Indian J Orthop. 2023;57(6):863-867. [CrossRef]

- Caplan AI, Correa D. The MSC: An Injury Drugstore. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(1):11-15. [CrossRef]

- Wickham MQ, Erickson GR, Gimble JM, Vail TP, Guilak F. Multipotent Stromal Cells Derived From the Infrapatellar Fat Pad of the Knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;412:196-212. [CrossRef]

- Sriwatananukulkit O, Tawonsawatruk T, Rattanapinyopituk K, Luangwattanawilai T, Srikaew N, Hemstapat R. Scaffold-Free Cartilage Construct from Infrapatellar Fat Pad Stem Cells for Cartilage Restoration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2022;28(5-6):199-211. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Chen S, Pei M. Comparative advantages of infrapatellar fat pad: an emerging stem cell source for regenerative medicine. Rheumatology. 2018;57(12):2072-2086. [CrossRef]

- Ding DC, Wu KC, Chou HL, Hung WT, Liu HW, Chu TY. Human Infrapatellar Fat Pad-Derived Stromal Cells have more Potent Differentiation Capacity than other Mesenchymal Cells and can be Enhanced by Hyaluronan. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(7):1221-1232. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Kuang L, Chen C, et al. miR-100-5p-abundant exosomes derived from infrapatellar fat pad MSCs protect articular cartilage and ameliorate gait abnormalities via inhibition of mTOR in osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2019;206:87-100. [CrossRef]

- Jeon Y, Kim J, Cho JH, Chung H, Chae J. Comparative Analysis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Bone Marrow, Placenta, and Adipose Tissue as Sources of Cell Therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(5):1112-1125. [CrossRef]

- Kouidhi M, Villageois P, Mounier CM, et al. Characterization of Human Knee and Chin Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Koh YG, Choi YJ. Infrapatellar fat pad-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2012;19(6):902-907. [CrossRef]

- Pei M. Environmental preconditioning rejuvenates adult stem cells’ proliferation and chondrogenic potential. Biomaterials. 2017;117:10-23. [CrossRef]

- Meng H, Lu V, Khan W. Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Potential Restorative Treatment for Cartilage Defects: A PRISMA Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(12):1280. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Song X, Li T, et al. Pellet coculture of osteoarthritic chondrocytes and infrapatellar fat pad-derived mesenchymal stem cells with chitosan/hyaluronic acid nanoparticles promotes chondrogenic differentiation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):264. [CrossRef]

- Ahearne M, Liu Y, Kelly DJ. Combining Freshly Isolated Chondroprogenitor Cells from the Infrapatellar Fat Pad with a Growth Factor Delivery Hydrogel as a Putative Single Stage Therapy for Articular Cartilage Repair. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(5-6):930-939. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Pei YA, Sun Y, Zhou S, Zhang XB, Pei M. Stem cells immortalized by hTERT perform differently from those immortalized by SV40LT in proliferation, differentiation, and reconstruction of matrix microenvironment. Acta Biomater. 2021;136:184-198. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Wu J, Xiang W, et al. Engineering exosomes derived from TNF-α preconditioned IPFP-MSCs enhance both yield and therapeutic efficacy for osteoarthritis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22(1):555. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa J, Uchida K, Takano S, et al. Regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide expression through the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE2 pathway in the infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17(1):215. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).