Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Participants and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Interventions and Injection Protocol

2.4. Follow-Up Schedule and Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Primary Outcome: Non-Inferiority of VAS and WOMAC Score Changes

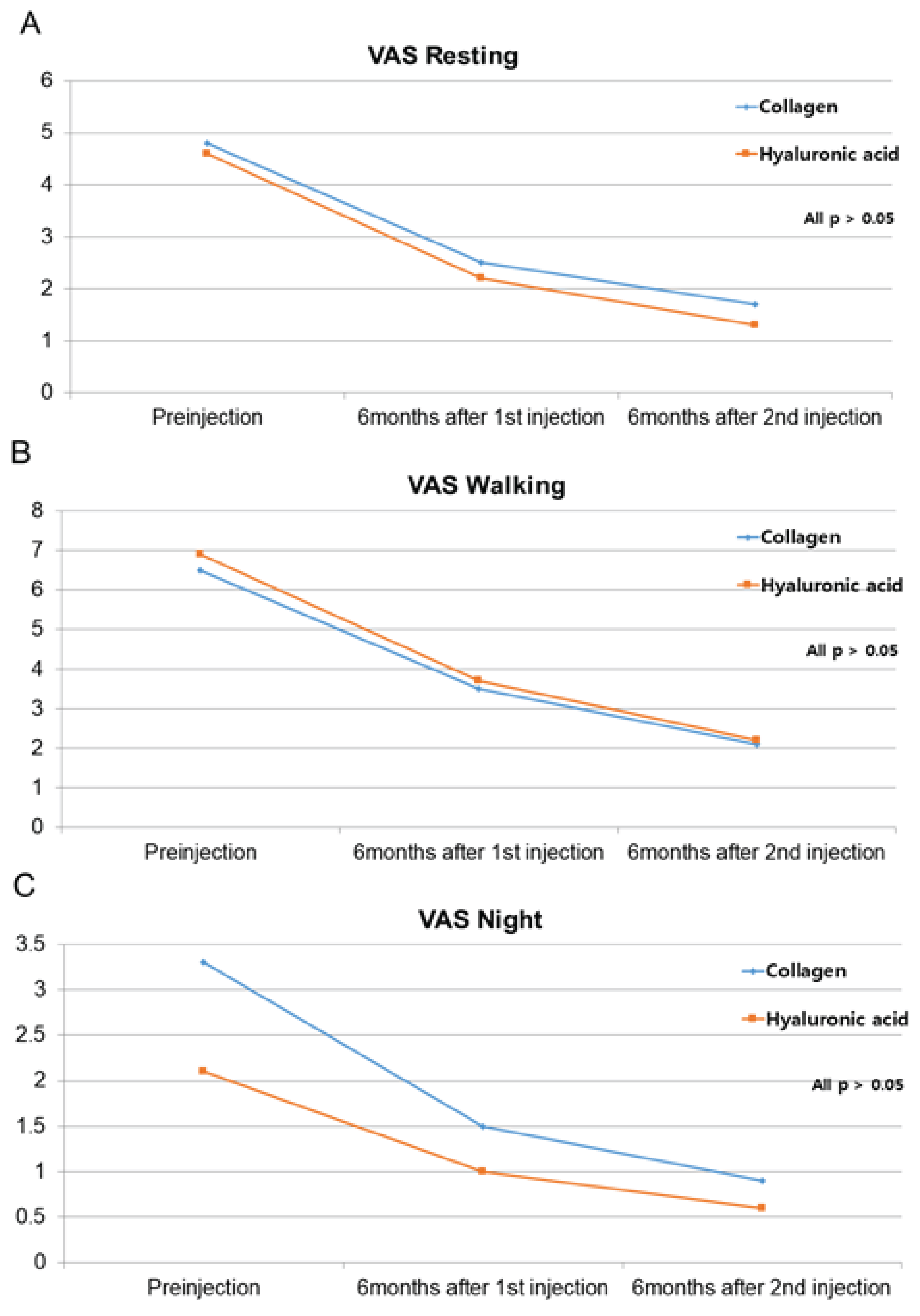

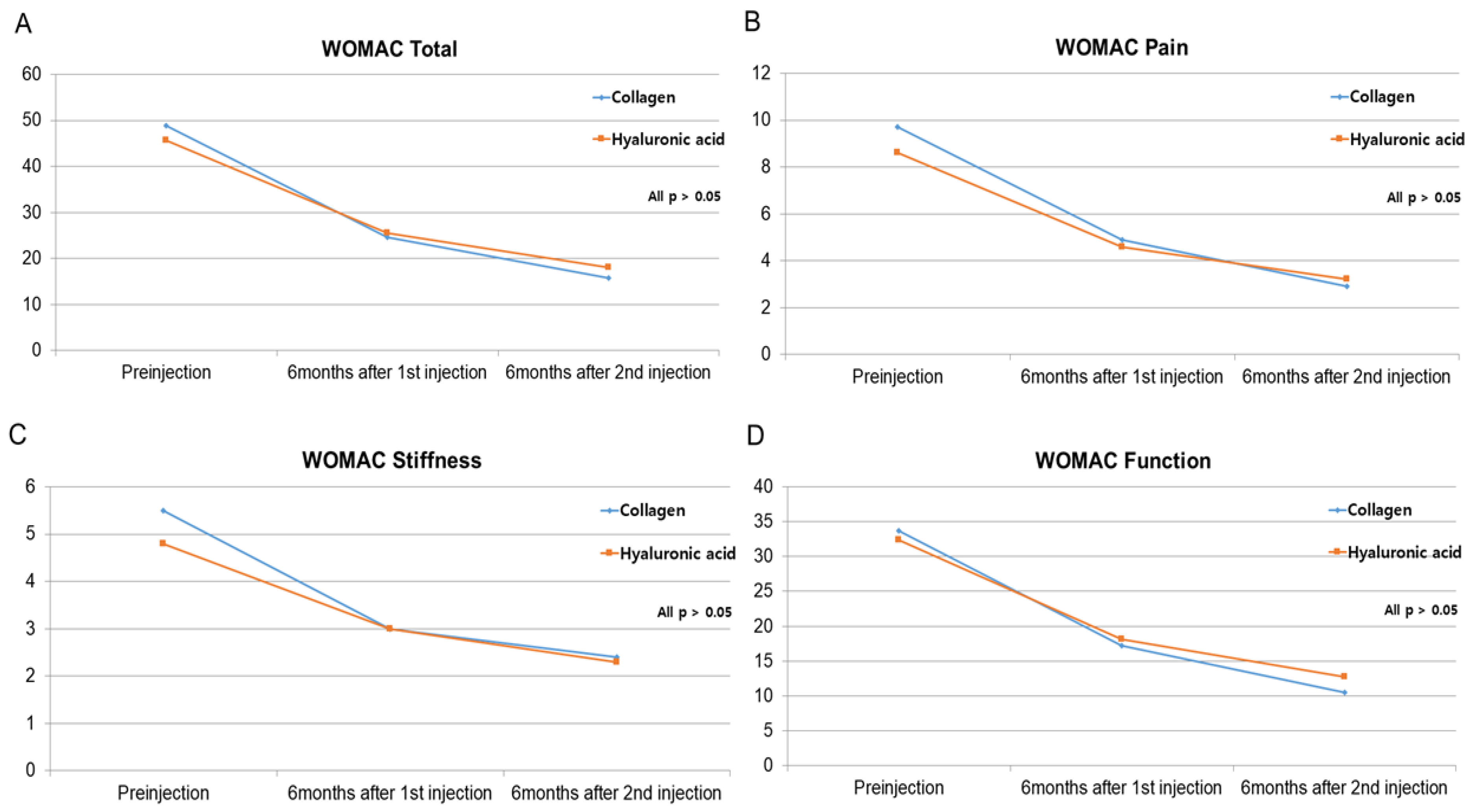

3.3. Secondary Outcome: VAS and WOMAC Scores

3.4. Patient Satisfaction

3.5. Adverse Events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choi, B.S.; Ro, D.H.; Lee, M.C.; Han, H.S. Isolated Polyethylene Insert Exchange for Instability after Total Knee Arthroplasty: Comparable Survival Rates and Range of Motion and Improved Clinical Scores Regardless of Hyperextension. Clin Orthop Surg 2024, 16, 550-558. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.E.; Tsai, M.H.; Wu, H.T.; Huang, J.T.; Huang, K.C. Phenotype-considered kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty for windswept-deformity-associated osteoarthritis: surgical strategy and clinical outcomes. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 16. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Park, Y.B.; Baek, S.H. Clinical and Radiological Outcomes of Computer-Assisted Navigation in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty for Patients with Extra-articular Deformity: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Orthop Surg 2024, 16, 430-440. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.K.; Kang, M.W.; Han, H.S. Do the Clinical and Radiological Features of Knees with Mucoid Degeneration of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Differ According to Knee Osteoarthritis Status? Clin Orthop Surg 2024, 16, 405-412. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Choi, B.S.; Ro, D.H.; Lee, M.C.; Han, H.S. Fixed-Bearing and Higher Postoperative Knee Flexion Angle as Predictors of Satisfaction in Asian Patients Undergoing Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg 2024, 16, 733-740. [CrossRef]

- Glyn-Jones, S.; Palmer, A.J.; Agricola, R.; Price, A.J.; Vincent, T.L.; Weinans, H.; Carr, A.J. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2015, 386, 376-387. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1745-1759. [CrossRef]

- Loeser, R.F.; Goldring, S.R.; Scanzello, C.R.; Goldring, M.B. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum 2012, 64, 1697-1707. [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Kraus, V.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Abbott, J.H.; Bhandari, M.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019, 27, 1578-1589. [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.N.; Arant, K.R.; Loeser, R.F. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. Jama 2021, 325, 568-578. [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.; Hackel, J.; Niazi, F.; Shaw, P.; Nicholls, M. Efficacy and safety of repeated courses of hyaluronic acid injections for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018, 48, 168-175. [CrossRef]

- Czarnocki, Ł.; Dębiński, M.; Sasinowski, T.; Runo, E.; Deszczyński, J. Collagen injections as an alternative therapy for musculoskeletal disorders. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol 2017, 82, 221-224.

- Milani, L. A new and refined injectable treatment for musculoskeletal disorders. Bioscaffold properties of collagen and its clinical use. Physiological Regulating Medicine 2010, 1, 3-15.

- Tarantino, D.; Mottola, R.; Palermi, S.; Sirico, F.; Corrado, B.; Gnasso, R. Intra-Articular Collagen Injections for Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.S.; Yoo, J.C.; Woo, S.H.; Kwak, A.S. Intra-Articular Atelocollagen Injection for the Treatment of Articular Cartilage Defects in Rabbit Model. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2021, 18, 663-670. [CrossRef]

- Borja-Flores, A.; Macías-Hernández, S.I.; Hernández-Molina, G.; Perez-Ortiz, A.; Reyes-Martínez, E.; Belzazar-Castillo de la Torre, J.; Ávila-Jiménez, L.; Vázquez-Bello, M.C.; León-Mazón, M.A.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; et al. Long-Term Effectiveness of Polymerized-Type I Collagen Intra-Articular Injections in Patients with Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation in a Cohort Study. Adv Orthop 2020, 2020, 9398274. [CrossRef]

- Misir, A.; Yildiz, K.I.; Kizkapan, T.B.; Incesoy, M.A. Kellgren-Lawrence grade of osteoarthritis is associated with change in certain morphological parameters. Knee 2020, 27, 633-641. [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011, 63 Suppl 11, S240-252. [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, N.; Buchanan, W.W.; Goldsmith, C.H.; Campbell, J.; Stitt, L.W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988, 15, 1833-1840.

- Tubach, F.; Ravaud, P.; Baron, G.; Falissard, B.; Logeart, I.; Bellamy, N.; Bombardier, C.; Felson, D.; Hochberg, M.; van der Heijde, D.; Dougados, M. Evaluation of clinically relevant changes in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the minimal clinically important improvement. Ann Rheum Dis 2005, 64, 29-33. [CrossRef]

- Waddell, D.D.; Cefalu, C.A.; Bricker, D.C. A second course of hylan G-F 20 for the treatment of osteoarthritic knee pain: 12-month patient follow-up. J Knee Surg 2005, 18, 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Sung, Y.G.; Park, D.C.; Lee, H.J.; In, Y. The Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) for the WOMAC and Factors Related to Achievement of the MCID After Medial Opening Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy for Knee Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2021, 49, 2406-2415. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Bhandari, M.; Grant, J.; Bedi, A.; Trojian, T.; Johnson, A.; Schemitsch, E. A Systematic Review of Current Clinical Practice Guidelines on Intra-articular Hyaluronic Acid, Corticosteroid, and Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Knee Osteoarthritis: An International Perspective. Orthop J Sports Med 2021, 9, 23259671211030272. [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.D.; Quartagno, M.; Clements, M.N.; Turner, R.M.; Nunn, A.J.; Dunn, D.T.; White, I.R.; Copas, A.J. Exploring different objectives in non-inferiority trials. Bmj 2024, 385, e078000. [CrossRef]

- Volpi, P.; Zini, R.; Erschbaumer, F.; Beggio, M.; Busilacchi, A.; Carimati, G. Effectiveness of a novel hydrolyzed collagen formulation in treating patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a multicentric retrospective clinical study. Int Orthop 2021, 45, 375-380. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, P.; Colombini, A.; Carimati, G.; Beggio, M.; de Girolamo, L.; Volpi, P. Intra-Articular Injection of Hydrolyzed Collagen to Treat Symptoms of Knee Osteoarthritis. A Functional In Vitro Investigation and a Pilot Retrospective Clinical Study. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Martin Martin, L.S.; Massafra, U.; Bizzi, E.; Migliore, A. A double blind randomized active-controlled clinical trial on the intra-articular use of Md-Knee versus sodium hyaluronate in patients with knee osteoarthritis ("Joint"). BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016, 17, 94. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Oh, K.J.; Moon, Y.W.; In, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kwon, S.Y. Intra-articular Injection of Type I Atelocollagen to Alleviate Knee Pain: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Cartilage 2021, 13, 342s-350s. [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.D.; Bedi, A.; Karlsson, J.; Sancheti, P.; Schemitsch, E. Product Differences in Intra-articular Hyaluronic Acids for Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Am J Sports Med 2016, 44, 2158-2165. [CrossRef]

- Migliore, A.; Procopio, S. Effectiveness and utility of hyaluronic acid in osteoarthritis. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2015, 12, 31-33. [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Muñoz-Chablé, O.A.; Macías-Hernández, S.I.; Agualimpia-Janning, A. Effect of polymerized-type I collagen in knee osteoarthritis. II. In vivo study. Eur J Clin Invest 2009, 39, 598-606. [CrossRef]

- Ohara, H.; Iida, H.; Ito, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Nomura, Y. Effects of Pro-Hyp, a collagen hydrolysate-derived peptide, on hyaluronic acid synthesis using in vitro cultured synovium cells and oral ingestion of collagen hydrolysates in a guinea pig model of osteoarthritis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2010, 74, 2096-2099. [CrossRef]

- Naraoka, T.; Ishibashi, Y.; Tsuda, E.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kusumi, T.; Toh, S. Periodic knee injections of collagen tripeptide delay cartilage degeneration in rabbit experimental osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2013, 15, R32. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Song, D.S.; Han, H.S.; Ro, D.H. Accurate, automated classification of radiographic knee osteoarthritis severity using a novel method of deep learning: Plug-in modules. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 24. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Schäfer, L.; Simeone, F.; Bell, A.; Hofmann, U.K. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID), substantial clinical benefit (SCB), and patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS) in patients who have undergone total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 3. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chaar, O.; Narayanakurup, J.; Abdelhamead, A.S.A.; Ro, D.H.; Kim, S.E. Do knee alignment patterns differ between Middle Eastern and East Asian populations? A propensity-matched analysis using artificial intelligence. Knee Surg Relat Res 2025, 37, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Yoon, T.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Seon, J.K. Radiologic Assessment of Knee Phenotypes Based on the Coronal Plane Alignment of the Knee Classification in a Korean Population. Clin Orthop Surg 2024, 16, 422-429. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Moon, S.W. Impacts of asymmetric hip rotation angle on gait biomechanics in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 23. [CrossRef]

| Collagen | Hyaluronic acid | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67.3±10.3 | 69.0±9.0 | 0.737 |

| Sex, female/male, n | 15/5 | 16/4 | 1 |

| BMI | 23.5±3.8 | 24.8±3.2 | 0.257 |

| Kellgren–Lawrence OA grade | 2.8±1.0 | 2.35±0.99 | 0.151 |

| II | 7(35%) | 10(50%) | 0.337 |

| III | 13(65%) | 10(50%) | |

| Injection site (Rt, %) | 14(70%) | 18(90%) | 0.235 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Hypertension | 11(55%) | 10(50%) | 0.751 |

| Diabetes | 4(20%) | 5(25%) | 1 |

| Thyroid disease | 4(20%) | 0(0%) | 0.106 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 6(30%) | 6(30%) | 1 |

| Pre-injection | |||

| VAS resting | 4.8±2.5 | 4.6±3.0 | 0.776 |

| VAS walking | 6.5±2.1 | 6.9±2.0 | 0.538 |

| VAS night | 3.3±3.3 | 2.1±2.5 | 0.299 |

| Total WOMAC | 48.9±14.9 | 45.7±20.6 | 0.583 |

| Pain WOMAC | 9.7±4.0 | 8.6±4.4 | 0.438 |

| Stiffness WOMAC | 5.5±2.1 | 4.8±2.2 | 0.281 |

| Function WOMAC | 33.7±10.3 | 32.4±15.3 | 0.745 |

| Collagen | Hyaluronic acid | Non-inferiority test (margin: VAS = 1.99) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | 95% CI | |||

| Pre-injection - 1st injection | ||||

| VAS resting | 2.3±2.0 | 2.4±2.2 | 0.004 | (-1.218, ∞) |

| VAS walking | 3.0±2.5 | 3.2±2.1 | 0.010 | (-1.433, ∞) |

| VAS night | 1.8±2.3 | 1.1±1.4 | <0.0001 | (-0.312, ∞) |

| Pre-injection - 2nd injection | ||||

| VAS resting | 3.1±2.1 | 3.3±2.6 | 0.011 | (-1.459, ∞) |

| VAS walking | 4.4±2.4 | 4.7±2.5 | 0.019 | (-1.635, ∞) |

| VAS night | 2.4±2.6 | 1.6±2.0 | 0.0003 | (-0.440, ∞) |

| Collagen | Hyaluronic acid | Non-inferiority test (margin: WOMAC = MCID) | Non-inferiority test (margin : WOMAC = SCB) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | 95% CI | p-value | 95% CI | |||

| Pre-injection - 1st injection | ||||||

| Total WOMAC | 24.3±11.0 | 20.1±10.4 | <0.0001 | (-1.502, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-1.502, ∞) |

| Pain WOMAC | 4.8±2.6 | 4.0±2.6 | <0.0001 | (-0.634, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-0.634, ∞) |

| Stiffness WOMAC | 2.5±1.7 | 1.8±1.3 | <0.0001 | (-0.043, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-0.043, ∞) |

| Function WOMAC | 16.5±7.8 | 14.2±7.3 | <0.0001 | (--1.724, ∞) | <0.0001 | (--1.724, ∞) |

| Pre-injection - 2nd injection | ||||||

| Total WOMAC | 33.2±12.8 | 27.6±14.9 | <0.0001 | (-1.858, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-1.858, ∞) |

| Pain WOMAC | 6.8±3.1 | 5.4±3.4 | <0.0001 | (-0.384, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-0.384, ∞) |

| Stiffness WOMAC | 3.1±1.9 | 2.5±1.9 | <0.0001 | (-0.372, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-0.372, ∞) |

| Function WOMAC | 23.2±8.9 | 19.7±10.5 | <0.0001 | (-1.651, ∞) | <0.0001 | (-1.651, ∞) |

| Collagen | Hyaluronic acid | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Six months after the 1st injection | 0.752 | ||

| No change (n, %) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | |

| Slightly improved (n, %) | 9(45%) | 10(50%) | |

| Very improved (n, %) | 11(55%) | 10(50%) | |

| Six months after the 2nd injection | 0.889 | ||

| No change (n, %) | 2(10%) | 3(15%) | |

| Slightly improved (n, %) | 15(75%) | 14(70%) | |

| Very improved (n, %) | 3(15%) | 3(15%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).