Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

21 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the challenges related to the accessibility and efficiency of the main modes of transportation?

- How do mobility dynamics influence urban organization and access to infrastructure?

- What solutions can be considered to improve the fluidity and sustainability of travel in the city?

2. Methodology

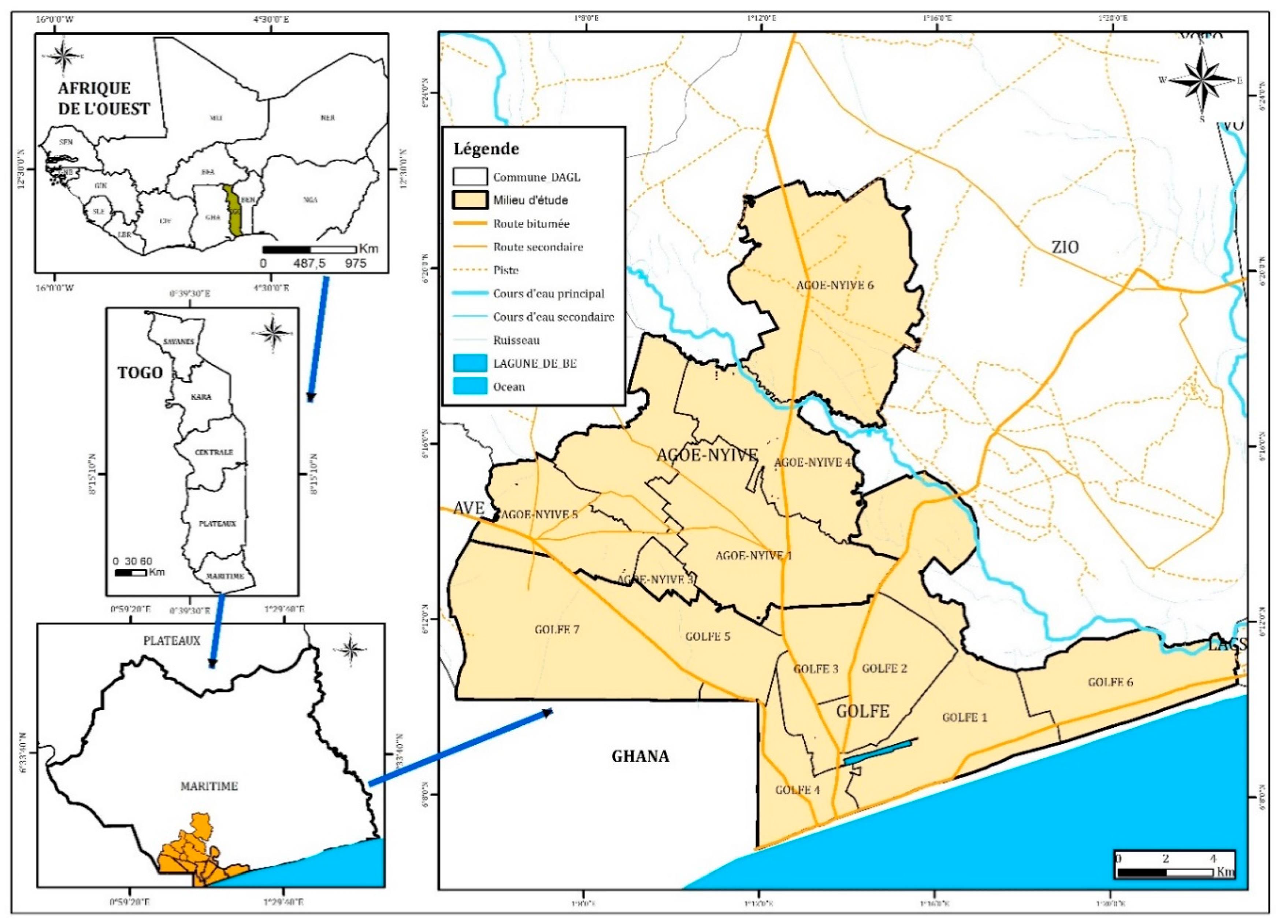

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- n is the sample size,

- Z is the Z-score corresponding to the confidence level (1.96 for a 95% confidence level),

- is the estimated proportion of the population with the characteristic of interest (0.5 when information is unknown to maximize variance),

- e is the margin of error (set at 0.05, or 5%).

2.3. Specific Challenges of Transportation Modes

2.3.1. Pedestrian Mobility: A Severe Lack of Adequate Infrastructure

2.3.2. Motorcycle Taxis: Safety Issues and Insufficient Regulation

2.3.3. Public Transport: Limited Coverage and Low Attractiveness

3. Results

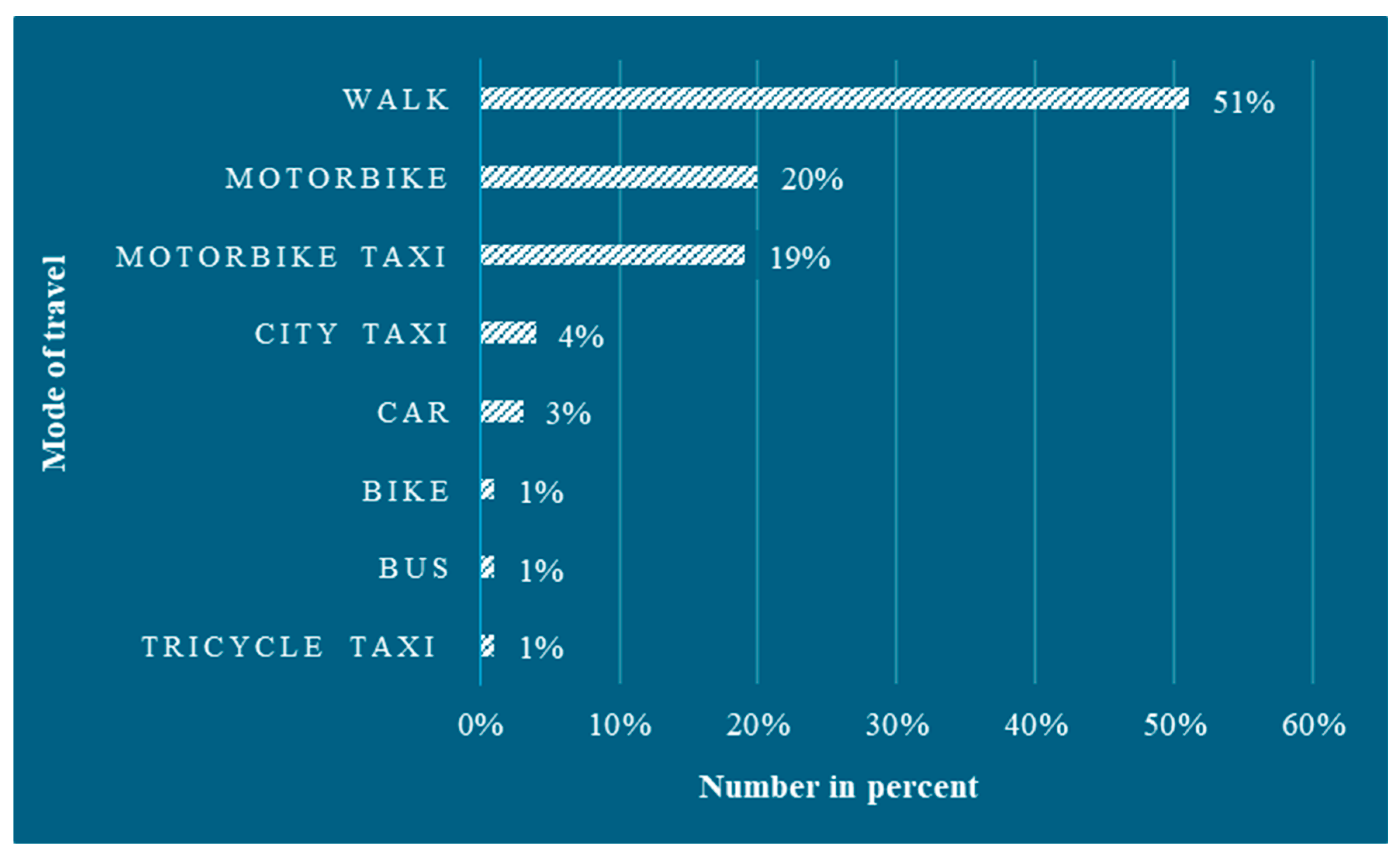

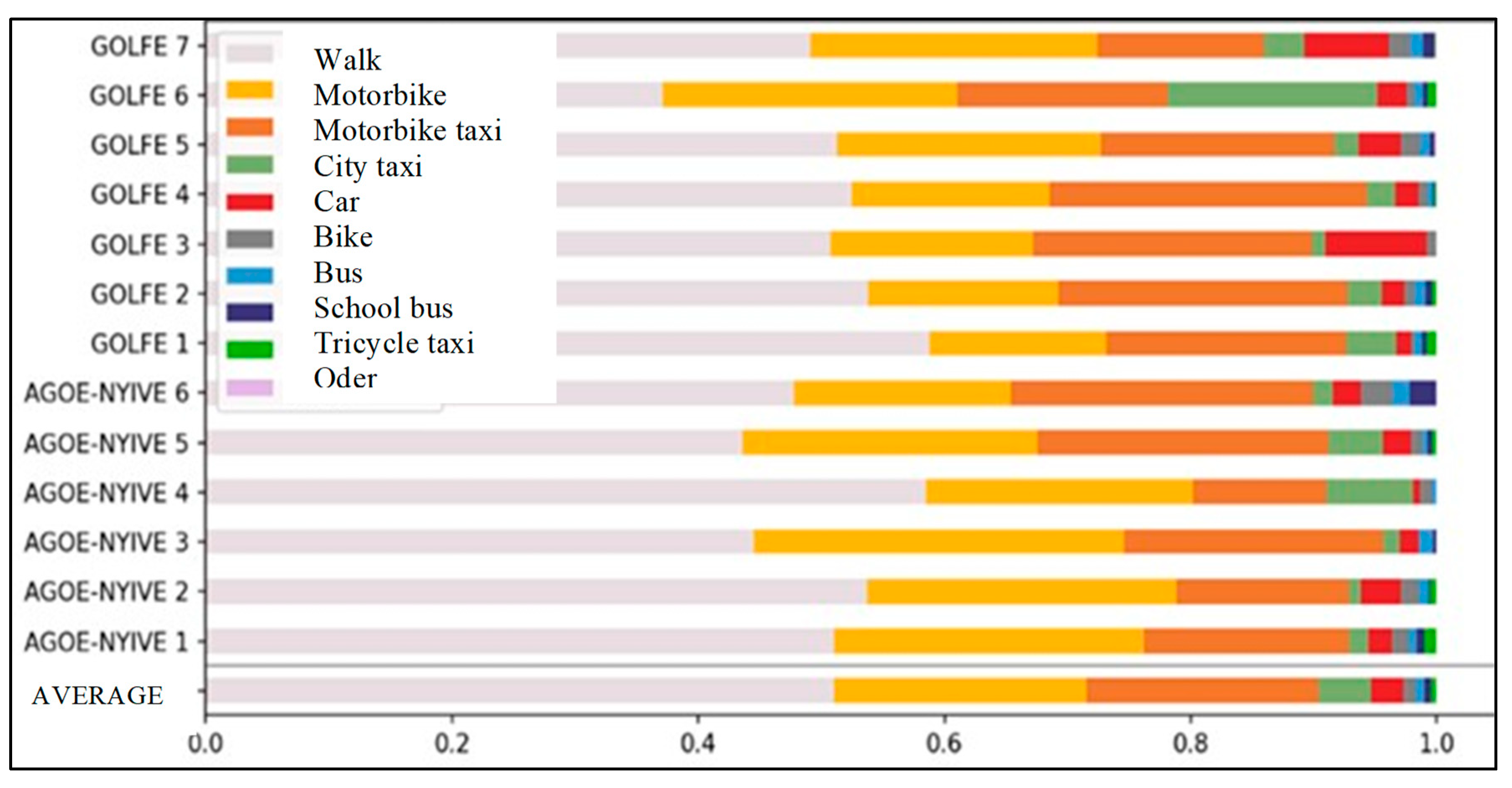

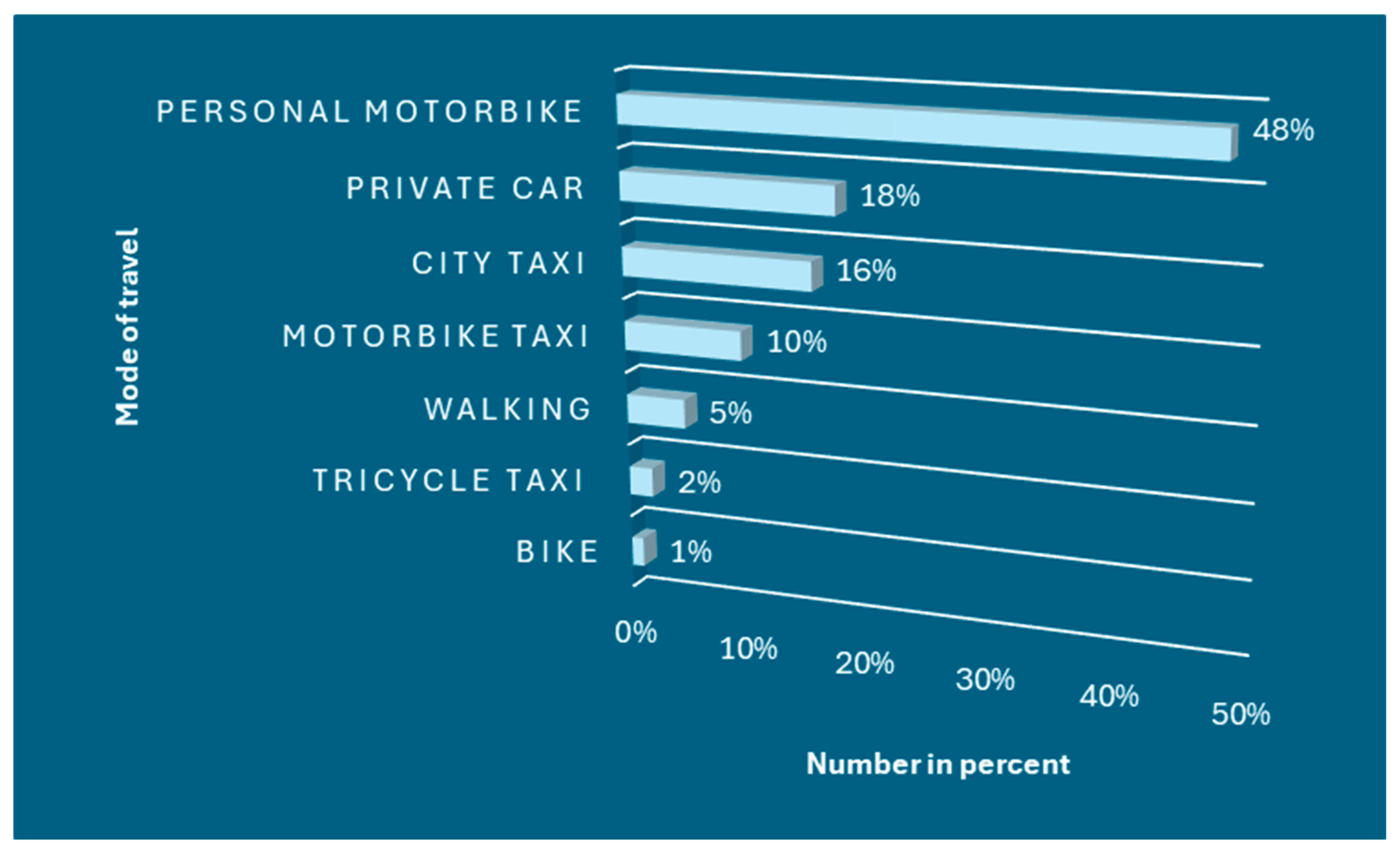

3.1. Transport Modes Used

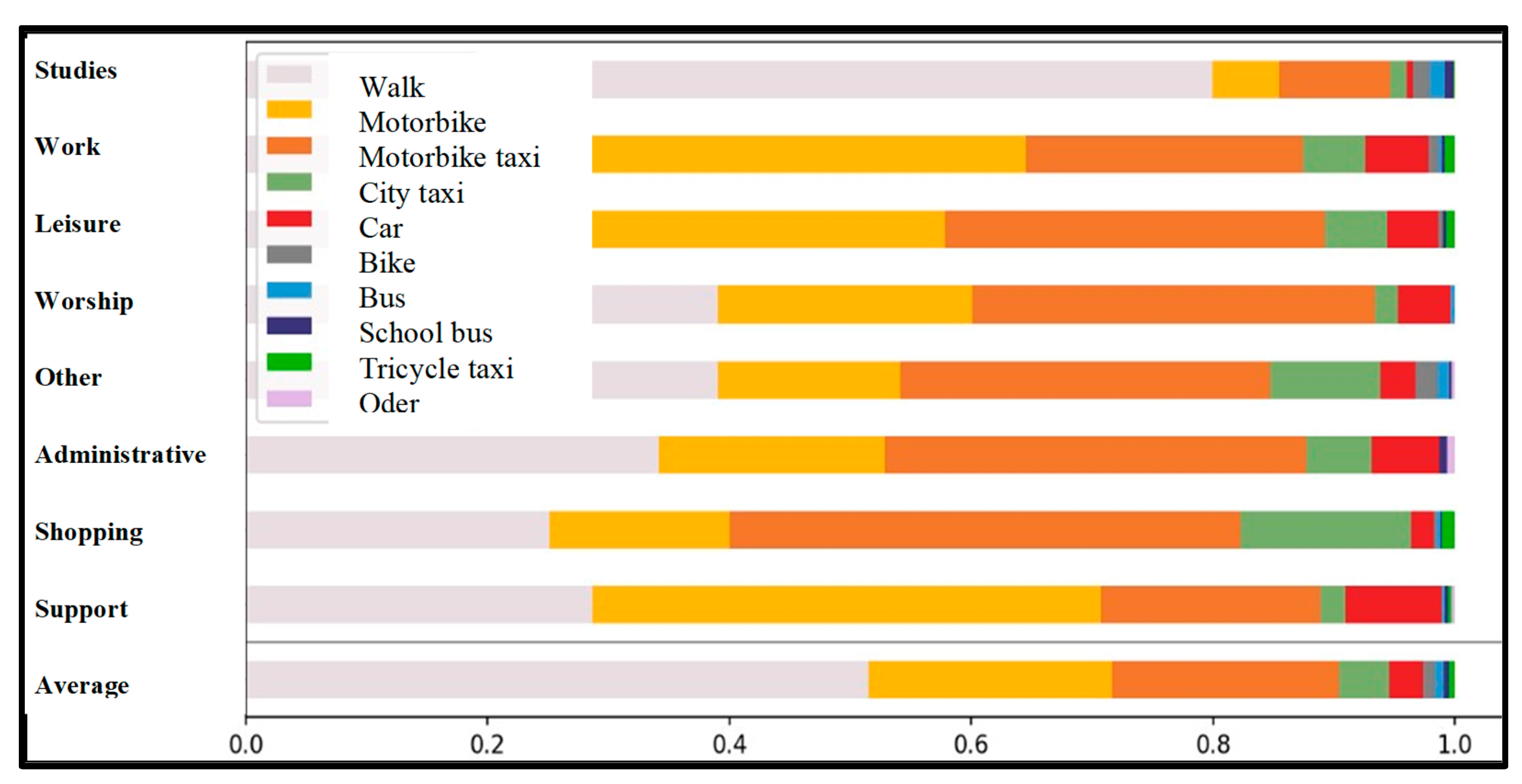

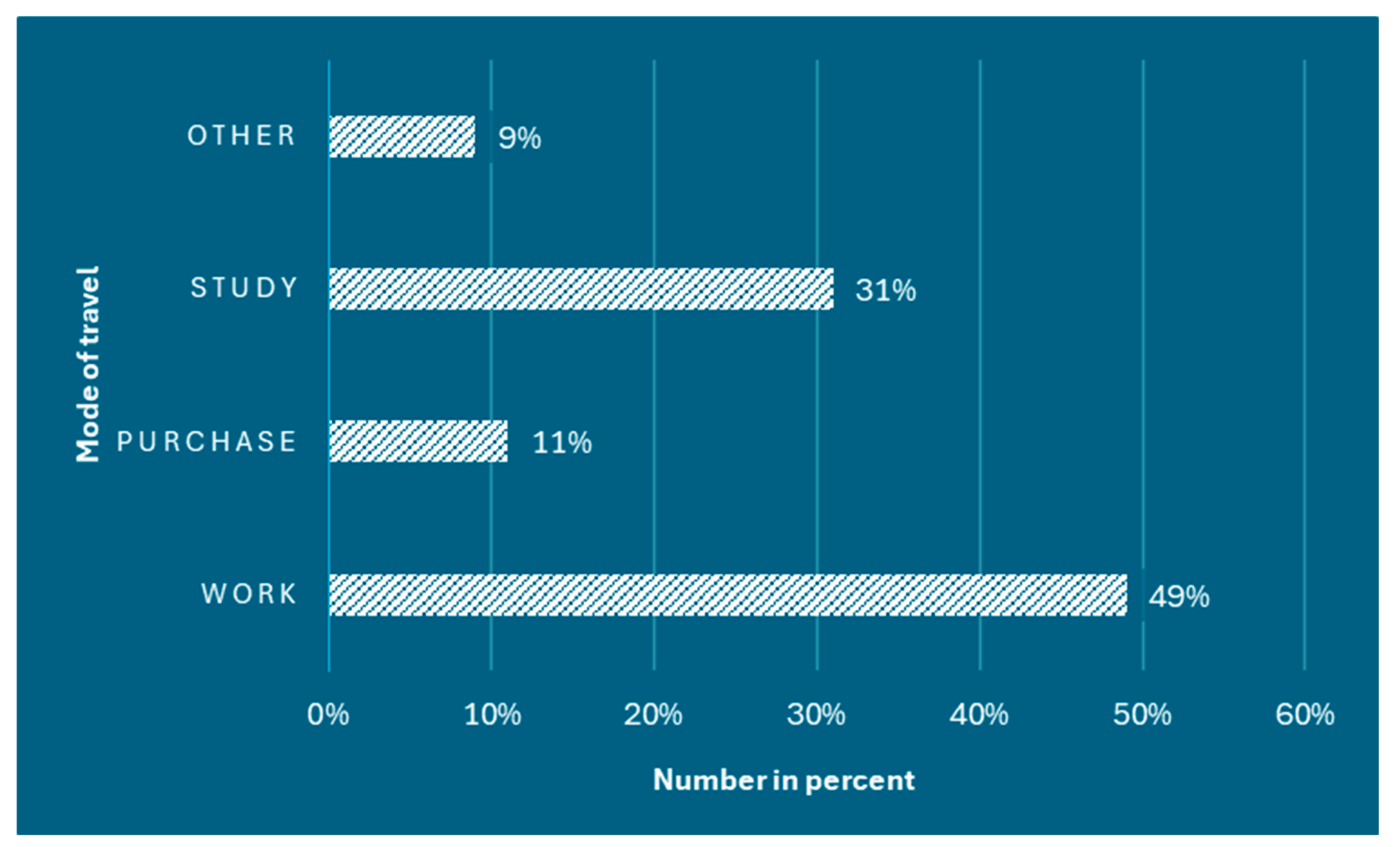

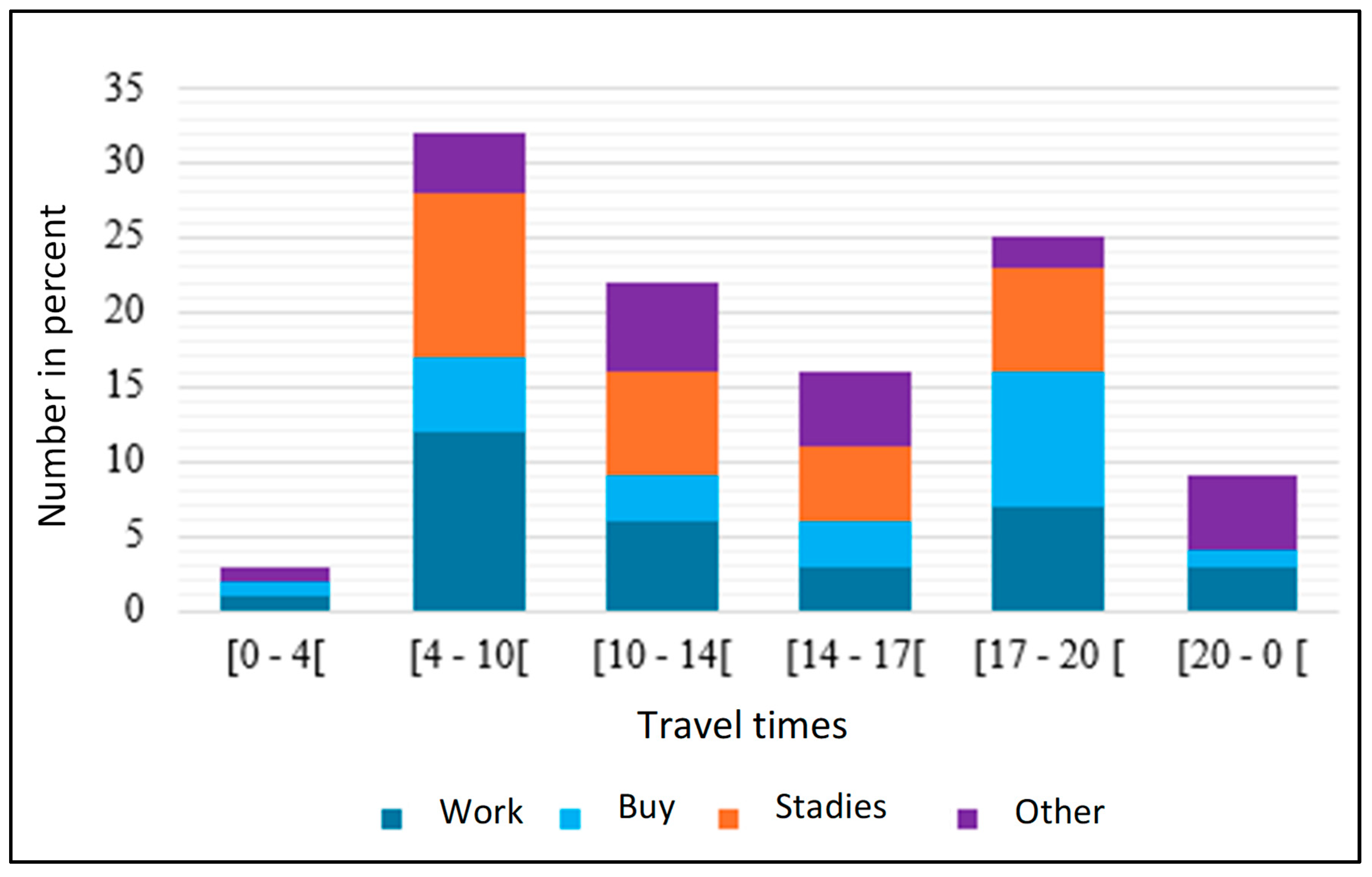

3.2. Reasons for Travel Among Lomé’s Population

3.3. Accessibility to Transport Modes and Cost

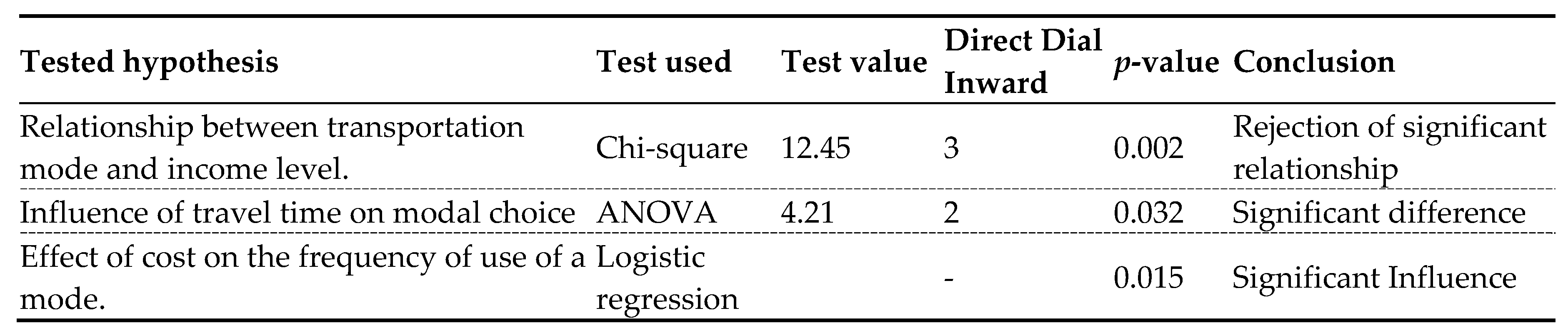

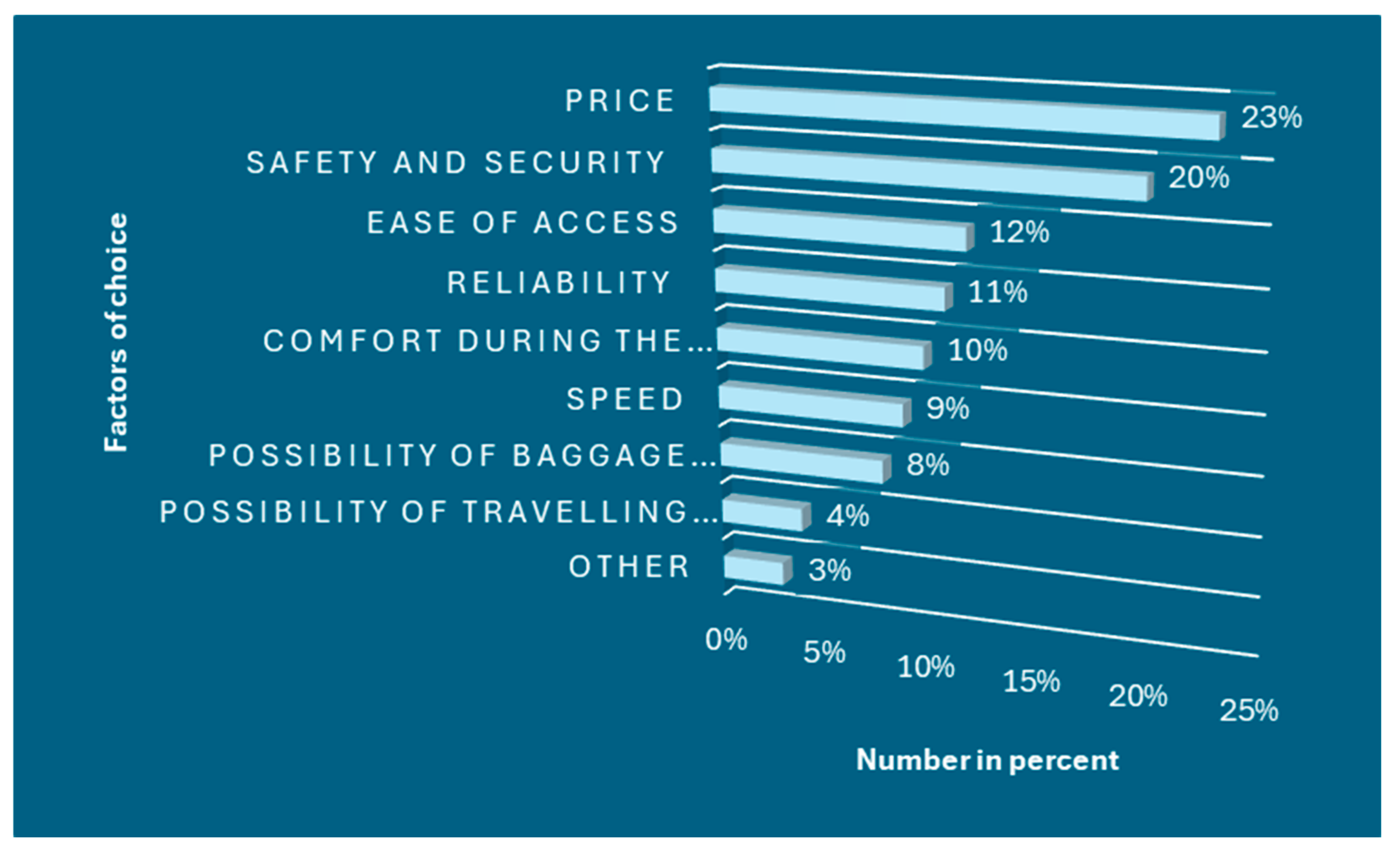

3.3.1. Factors Influencing Transport Mode Choice

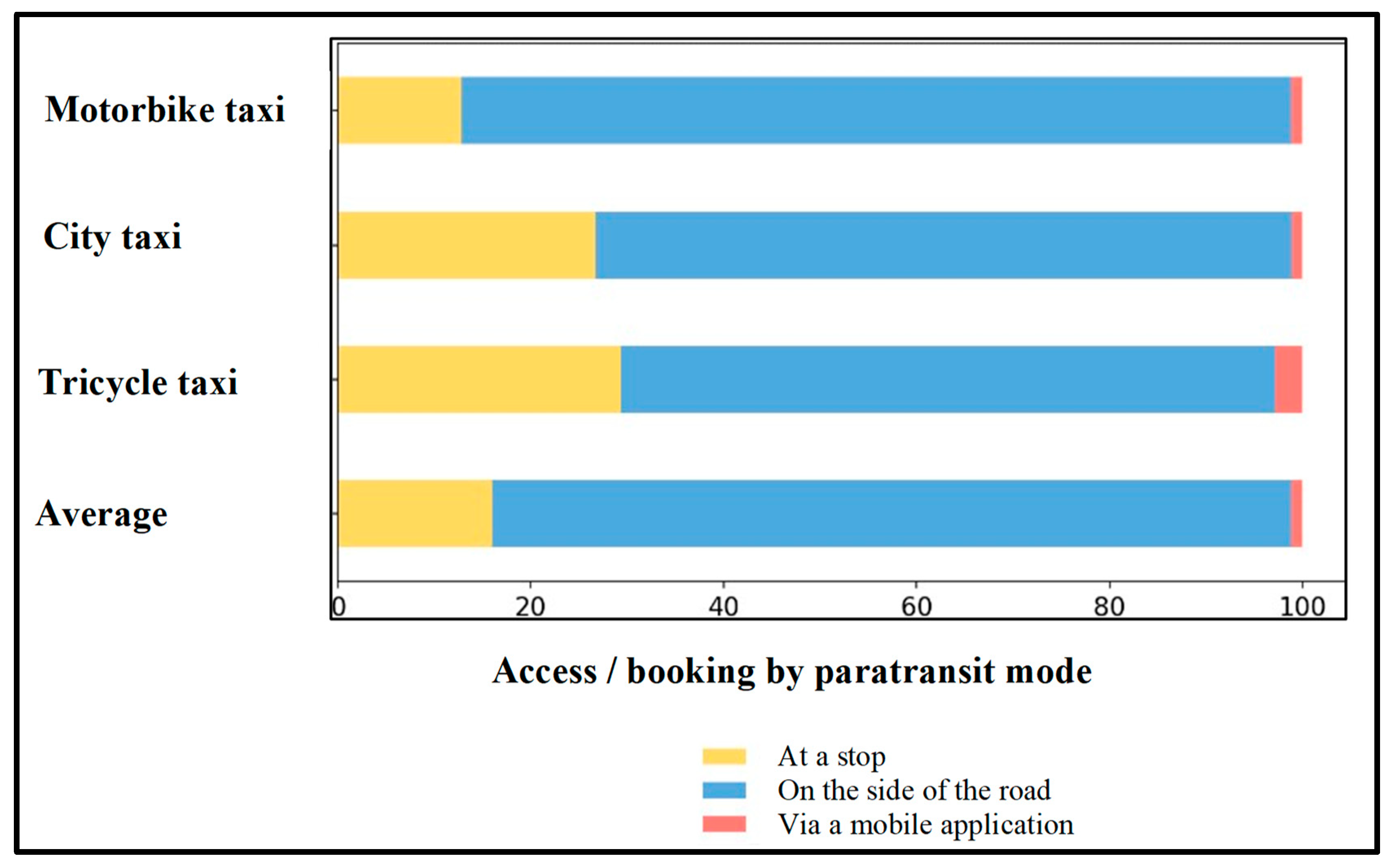

3.3.2. User Perception of Transport Modes

- By the roadside

- At a designated stop

- Using a mobile app (such as Gozem or others)

- Traditional habits of hailing transport on the roadside,

- Limited digital literacy among users,

- Restricted mobile internet access in certain areas of Greater Lomé.

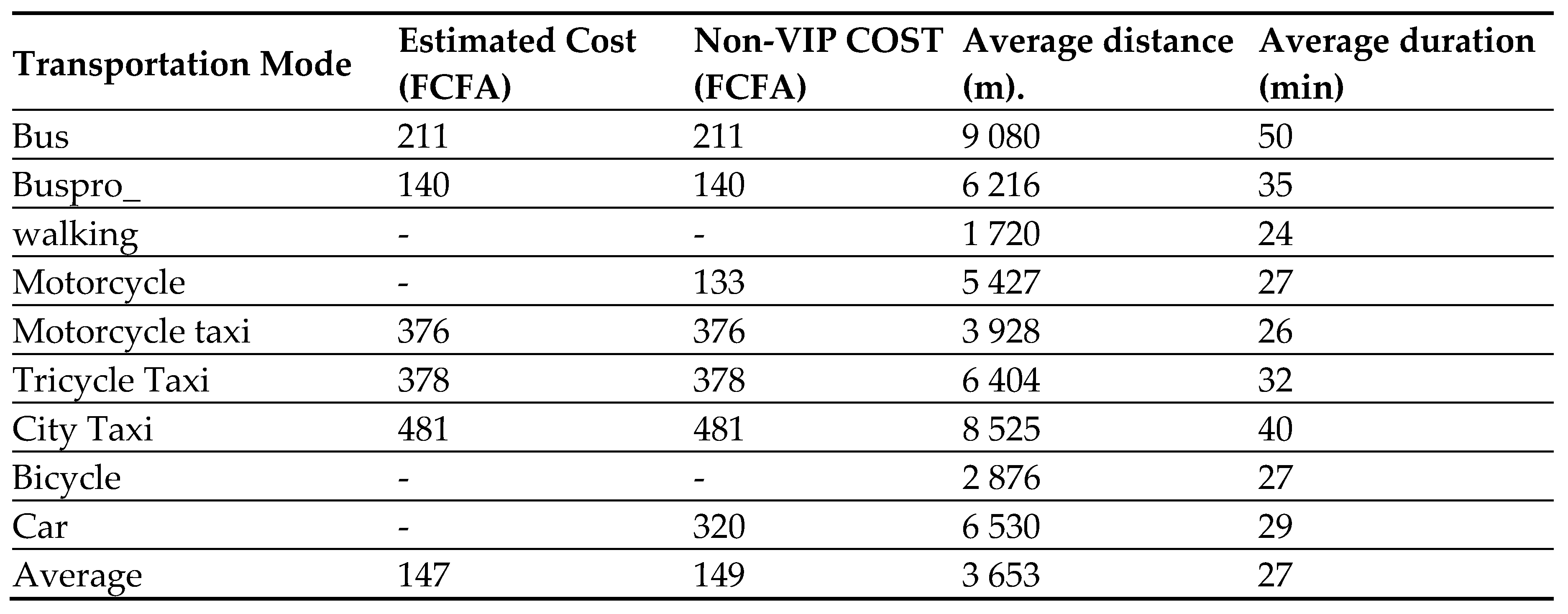

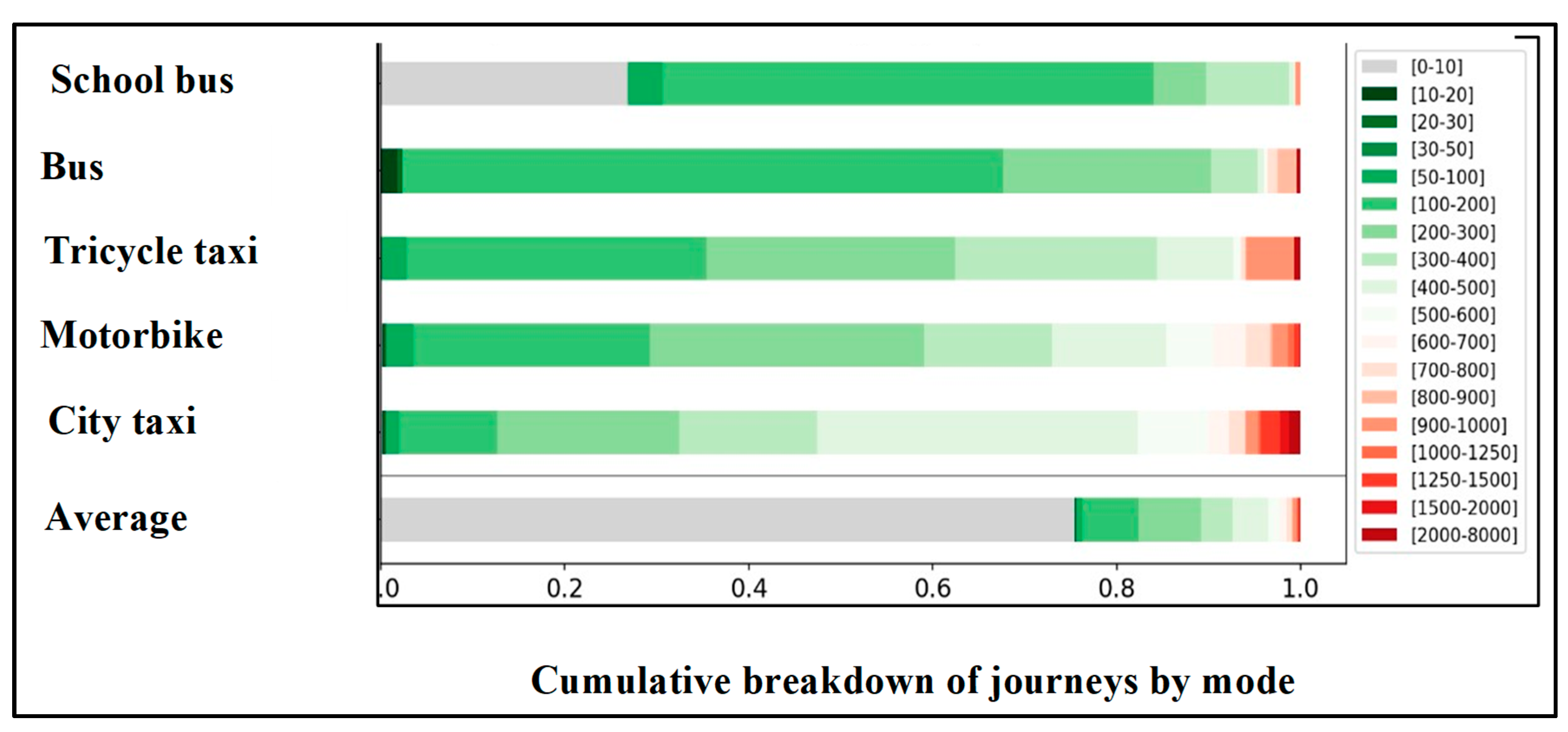

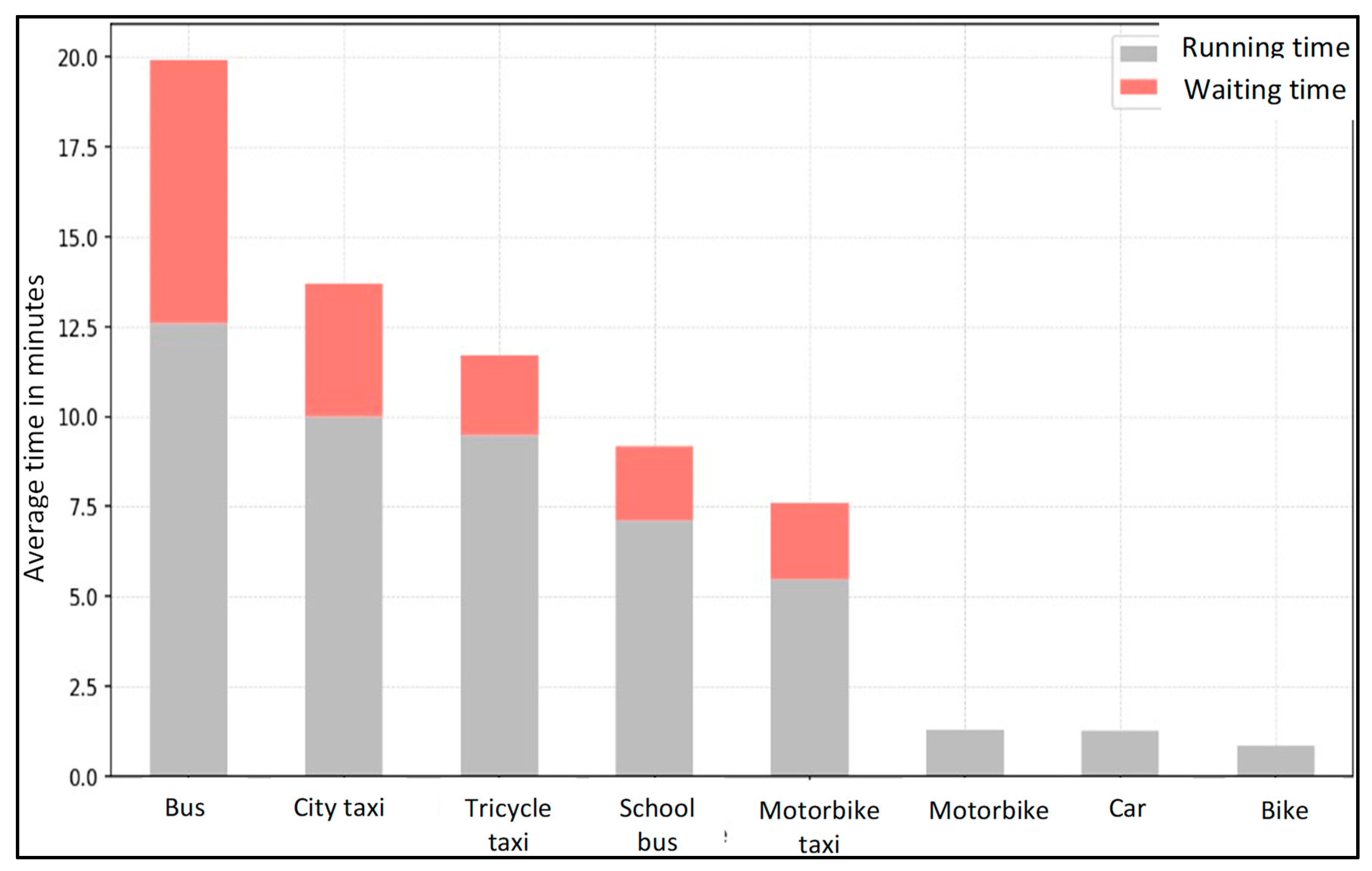

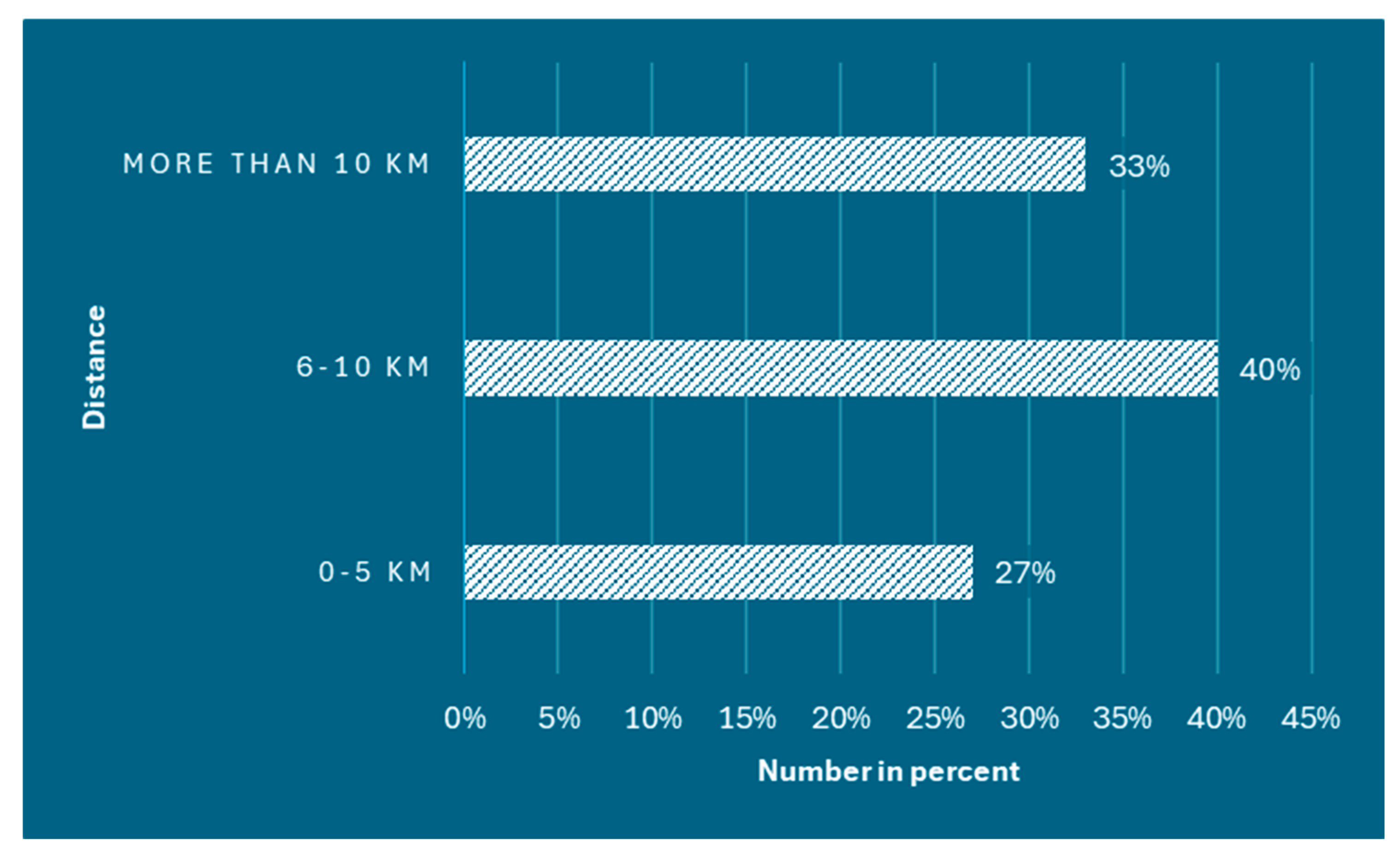

3.3.3. Cost, Duration, and Average Daily Travel Distance by Mode

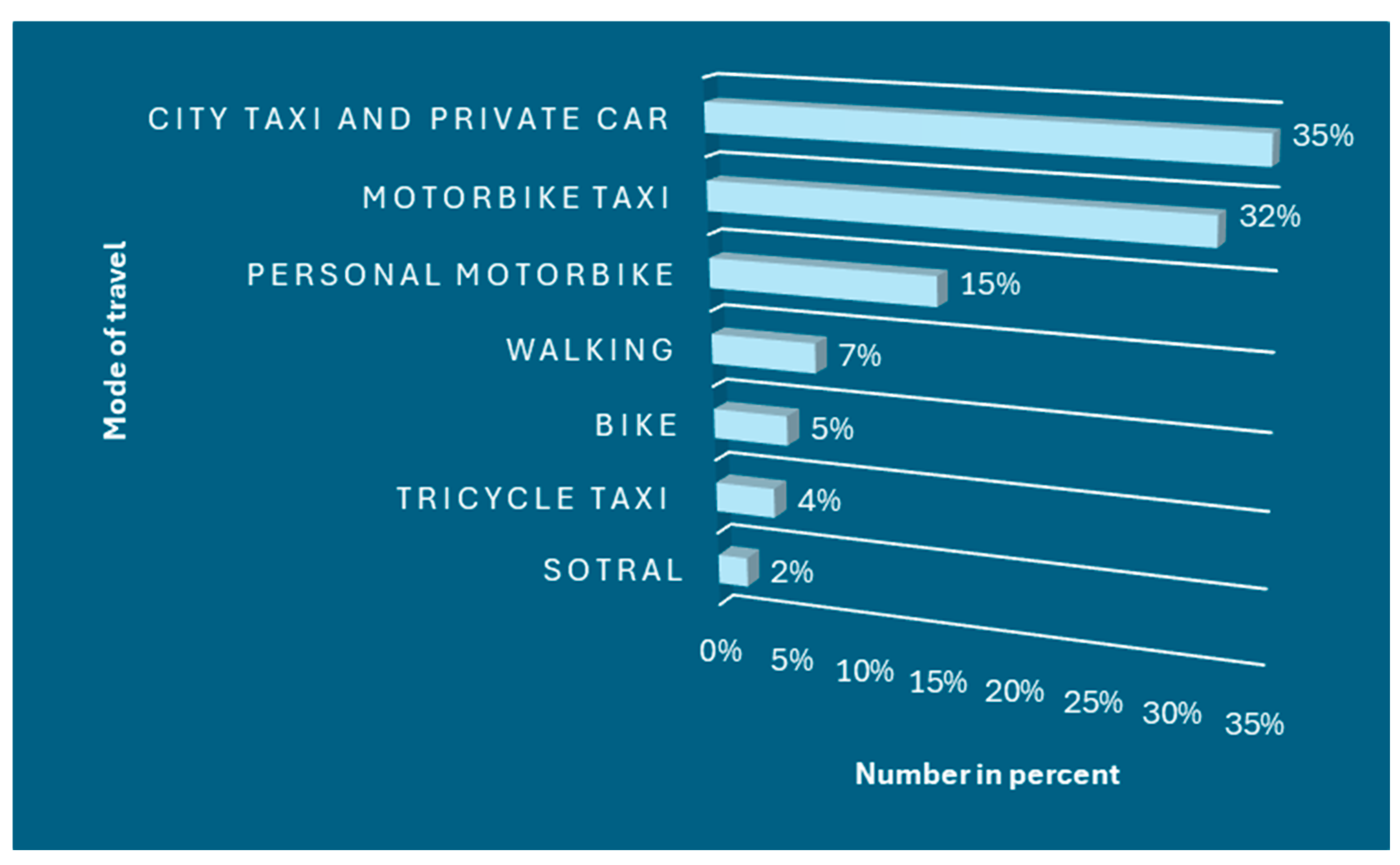

3.4. Motorized Two-Wheelers: A Dominant Mode of Transport on the Roads of Greater Lomé

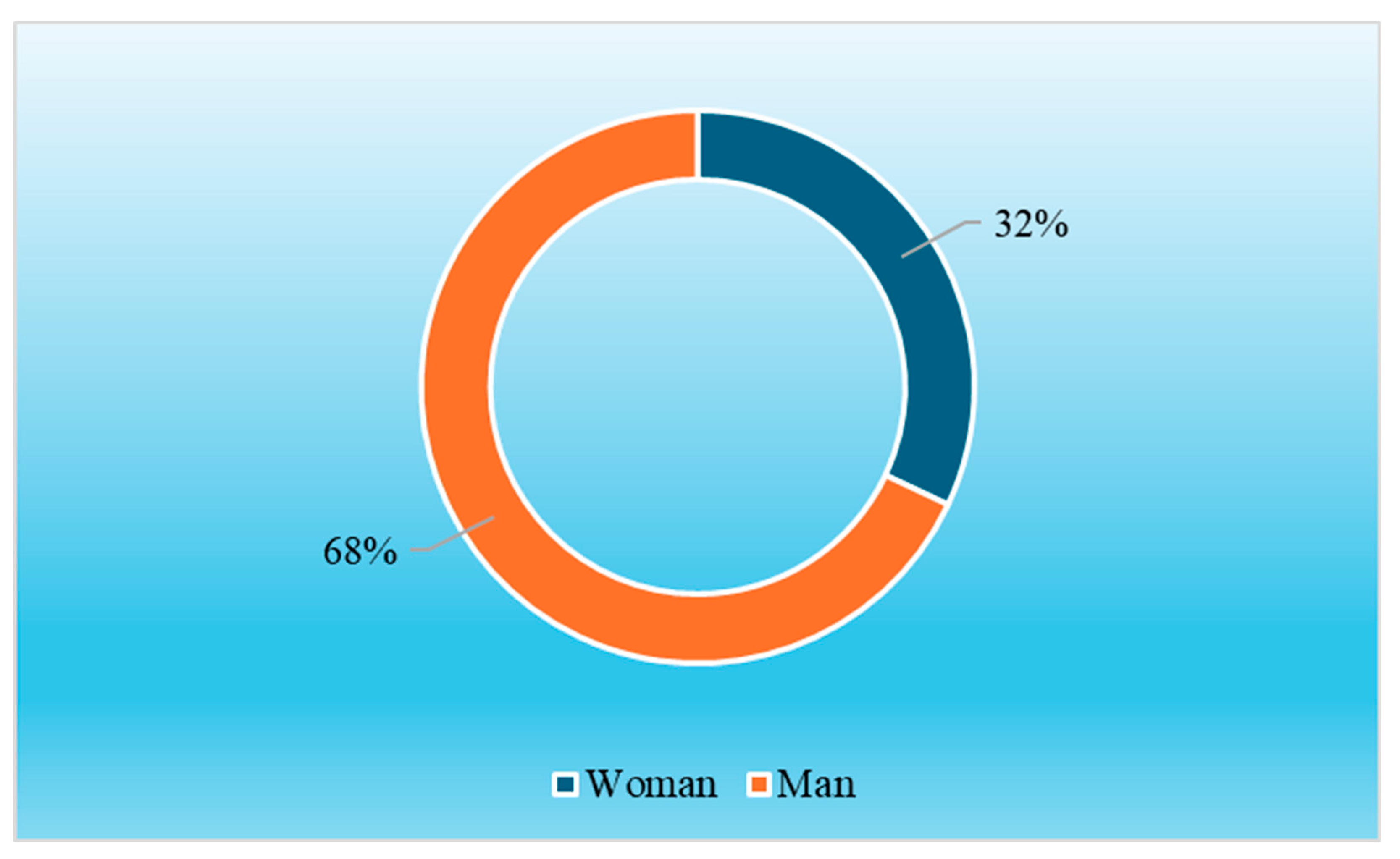

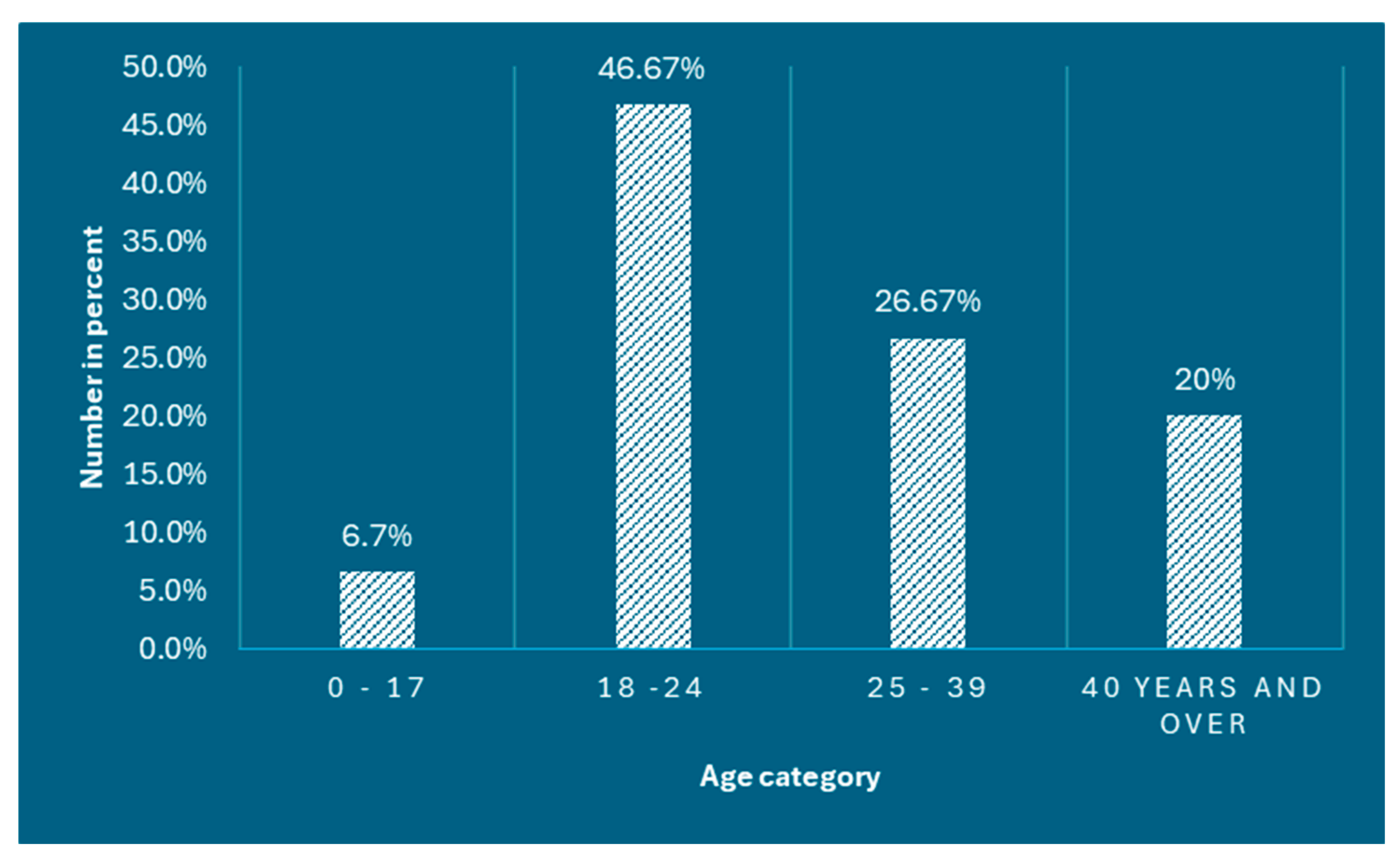

3.4.1. Profiles of Active Mode Users on the Main Roads of Greater Lomé

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. (2022). Urban mobility in West Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Diaz Olvera, L., Kane, C., & Suka, D. (2015). Urban mobility in West Africa: A comparative analysis. Transport Studies Journal, 23(4), 112–134.

- World Health Organization. (2011). Road safety and urban infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa. Geneva: WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/africa_infrastructure/en/.

- Alawi, A. (2017). Informal transport and regulation in Africa. Bamako: African Editions.

- Klopp, J., & Behrens, R. (2017). Africa’s transport challenges: Policies and solutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/africas-transport-challenges/ ...

- SSATP. (2019). Sustainable Urban Transport in Africa. World Bank.

- INSEED. (2022). Final results of the Fifth General Census of Population and Housing (RGPH-5), November 2022. National Institute of Statistics and Economic and Demographic Studies. https://inseed.tg/resultats-definitifs-du-rgph-5-novembre-2022/.

- DGSCN. (2010). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) – Final Report. Lomé, Togo: Directorate General of Statistics and National Accounting.

- Togbedji, T. (2020). Studies on Urban Mobility Dynamics in West Africa. Lomé: University Press.

- Blivi, A. (1998). Urban Morphology and Geography of Lomé. Lomé: University Editions.

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Passoli, A., et al. (2024). Fieldwork on mobility practices and challenges in Greater Lomé. Lomé.

- Diaz Olvera, L., & Kane, C. (2002). Urban Mobility and Transport in West Africa. Paris: CNRS Editions. Available at: https://www.editions.cnrs.fr/livre/9782271060000.

- Suka, D. (2021). Urban mobility in African cities: Challenges and solutions (p. 131). Dakar: African Editions.

- Edoh, K. (2014). Daily Mobility in Africa: Challenges and Perspectives. Abidjan: African University Editions.

- Amar, G. (1993). Transport and Development in Black Africa: An Economic Geography Essay. Paris: Karthala.

- Quénot-Suarez, H. (2011). Cyclical Mobility and Urban Transport. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Road Safety in Sub-Saharan Africa. Geneva: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries ...

- SSATP. (2019). Sustainable Urban Transport in Africa. World Bank.

- Jennings, G., & Behrens, R. (2017). Paratransit in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current trends and future prospects. London: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Paratransit-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa-Current-Trends-and-Future-Prospects/Jennings-Behrens/p/book/9781138287846.

- Salon, D., & Gulyani, S. (2010). Mobility, accessibility, and poverty in African cities: Evidence from Nairobi and Accra. World Bank Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ghana Transport Ministry. (2023). Pedestrian infrastructure improvement in Accra. Accra: Government of Ghana.

- Gathara, P. (2018). Regulating informal transport in East Africa: Challenges and successes. African Transport Review, 17(2), 55–78.

- World Bank. (2012). World development report 2012: Gender equality and development. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Ministry of Transport of Benin. (2023). Regulation of Zemidjans in Cotonou. Cotonou: Government of Benin.

- Ministry of Transport of Burkina Faso. (2023). Reforms and modernization of urban transport in Ouagadougou. Ouagadougou: Government of Burkina Faso.

- GSMA. (2023). Mobile Technology and Transportation in Africa. GSMA Intelligence Report. Available at: https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/.

- PMUD-GN. (2025). Final report of the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) of the Sustainable Urban Mobility Project of Grand Nokoué. Cotonou, Benin: Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport.

- African Development Bank. (2021). Urban mobility strategies in Africa. Abidjan: African Development Bank Group. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/document/urban-mobility-strategies-in-africa-2021-110693.

- SSATP. (2019). Sustainable Urban Transport in Africa. World Bank.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).