1. Introduction

Modern physics, through quantum mechanics and general relativity, has revealed many facets of nature. These theories have achieved remarkable successes at both microscopic and macroscopic scales, yet a unified and mechanistic foundational theory remains elusive.

The Standard Model describes three fundamental forces—electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear—via gauge bosons, but it does not provide a mechanistic explanation for their origin. It fails to incorporate gravity and cannot account for the nature of dark matter and dark energy. On the other hand, general relativity characterizes gravity as curvature of spacetime, but breaks down at the Planck scale, becoming incompatible with quantum principles, and lacks a particle-based source for mass, inertia, and time.

Contemporary cosmology, largely based on the Big Bang paradigm, invokes notions such as singularity and inflation. This model does not offer a mechanistic explanation for the origin of the universe, entropy imbalance, or the directional flow of events. As a result, different branches of modern physics remain compartmentalized, and an overarching consistent picture of physical reality is still lacking.

In light of these theoretical limitations, we propose a deterministic, coherent, and testable alternative: the “Absolute Equation of Universe Creation.” This framework is founded entirely on the interaction of two fundamental particles—K (negative energy, source of attraction and inertia) and D (positive energy, source of motion and radiation). The formalism and core equations defining this framework are detailed in subsequent sections.

Two fundamental particles:

K particles (negative energy, ): sources of attraction and inertia

D particles (positive energy, ): carriers of motion, radiation, and mass

Their total energy remains conserved as . An effective attractive force between them, scaling as , gives rise to mass, gravity, light, quantum entanglement, and atomic structure—eliminating the need for spacetime fabric, field quantization, or abstract constructs from the dark sector.

This theory rests on the following core equations:

Mass equation:

Energy equation:

Entropy asymmetry:

We explicitly predict particle-level structures:

In addition, several large-scale phenomena—such as Venus’s retrograde rotation, photon generation from hydrogen fusion, and the presence of cold black hole cores—arise naturally within this framework. A fundamental conclusion of this theory is that every physical phenomenon occurring in the entire universe is a direct consequence of the interaction between only two fundamental energy particles: K and D. Beyond these two, no independent particle exists in the universe; all known physical structures are formed from their combinatorial states. Furthermore, it is proposed that both K and D particles originate from a single primordial energy source, and that the entire diversity of matter and energy emerges solely from their mutual dynamics.

Thus, the K–D framework not only simplifies the conceptual complexity of conventional models but also provides a unified, deterministic, and experimentally testable foundation across atomic, astrophysical, and cosmological scales.

In addition to the concise presentation in this paper, detailed mathematical derivations, extended discussions, and supplementary data supporting this framework are provided in the Supplementary Information.

2. Fundamental Hypotheses of the Absolute Equation of Universe Creation

The Absolute Equation of Universe Creation, grounded in the interaction between two fundamental energy particles—K (negative energy attractor) and D (positive energy radiator)—provides a unified framework explaining all physical phenomena. This includes the origin of mass, time, entropy, light, and gravity. The central tenet asserts that mass is not fundamental but instead emerges from K–D pair bonding energy.

2.1. Primordial Duality Hypothesis

We postulate that the universe originated from a primordial energy unit , which underwent spontaneous symmetric splitting into:

The total energy remains conserved:

This eliminates the need for hypothetical concepts like dark energy, Big Bang singularity, and dark matter.

2.2. Physical Consistency

The K–D Theory describes fundamental particle interactions using negative-energy (K) and positive-energy (D) particles. The model is tested for mathematical and physical consistency, dimensional analysis, and explicit mass calculations for known particles (proton, neutron, electron, photon).

2.3. Core Equations

Mass equation:

Energy equation:

Entropy asymmetry:

2.4. Predicted Particle-Level Structures

This foundation allows key physical phenomena—such as mass, gravity, light, quantum entanglement, and atomic structure—to arise naturally without the need for spacetime curvature, field quantization, or abstract constructs from the dark sector.

3. Mathematical Framework

This section presents the mathematical formulation of the division of energy and field in the proposed unified energy-based framework for the origin and evolution of the universe. The model explains the origin of K (negative, energy-deficient) and D (positive, potential energy) particles through a cyclical imbalance, which forms the foundation of cosmic structures and physical phenomena such as mass, gravity, and light.

3.1. Primordial Energy Particle: Field and Energy

We begin by assuming the universe arose from the division of a primordial energy particle, with total energy and spatial extent :

3.2. Spatial and Energy Division

The spatial field

and energy

divide equally:

Total energy remains conserved:

3.3. K–D Attractive Force

An attractive central force between

K and

D particles is defined as:

where

k is the coupling constant, and

r is the mean separation between particles.

3.4. Mass Equation

The mass originating from the K–D interaction is given by:

where

K and

D are the number of

K and

D particles,

k is the coupling constant,

r is the mean separation distance, and

is the fundamental energy unit.

3.5. Energy Equation

The energy associated with the system is simply:

3.6. Entropy Asymmetry

Cosmic entropy is defined due to the

imbalance:

3.7. Summary of Key Variables

m: mass

K, D: number of K and D particles

k: K–D coupling constant

r: mean separation (nuclear scale)

: fundamental energy unit

This formalism unifies the emergence of mass, gravity, light, and entropy in a single mechanistic framework, providing a predictive foundation for further calculations.

3.8. Physical Consistency

The K—D Theory describes fundamental particle interactions using the dynamics of negative-energy (K) and positive-energy (D) particles. This section verifies the mathematical and physical consistency of the theory’s fundamental equations in SI units, through dimensional analysis, calibrated constants, and explicit mass calculations for the proton, neutron, electron, and photon, compared with experimental data.

3.8.1. Symbols and SI Units

Table 1.

Symbols and SI Units used in the theory.

Table 1.

Symbols and SI Units used in the theory.

| Symbol |

Definition |

SI Unit |

| m |

Mass |

kg |

|

Number of K and D particles |

– |

| k |

K—D coupling constant |

kg·m4·s−2

|

| r |

Mean separation (nuclear scale) |

m |

|

Reference separation for electron |

m |

|

Fundamental energy unit |

J (kg·m2·s−2) |

|

Photon micro dynamic mass |

kg |

|

Effective D-particle number (electron) |

– |

| c |

Speed of light |

m·s−1

|

| h |

Planck constant |

J·s |

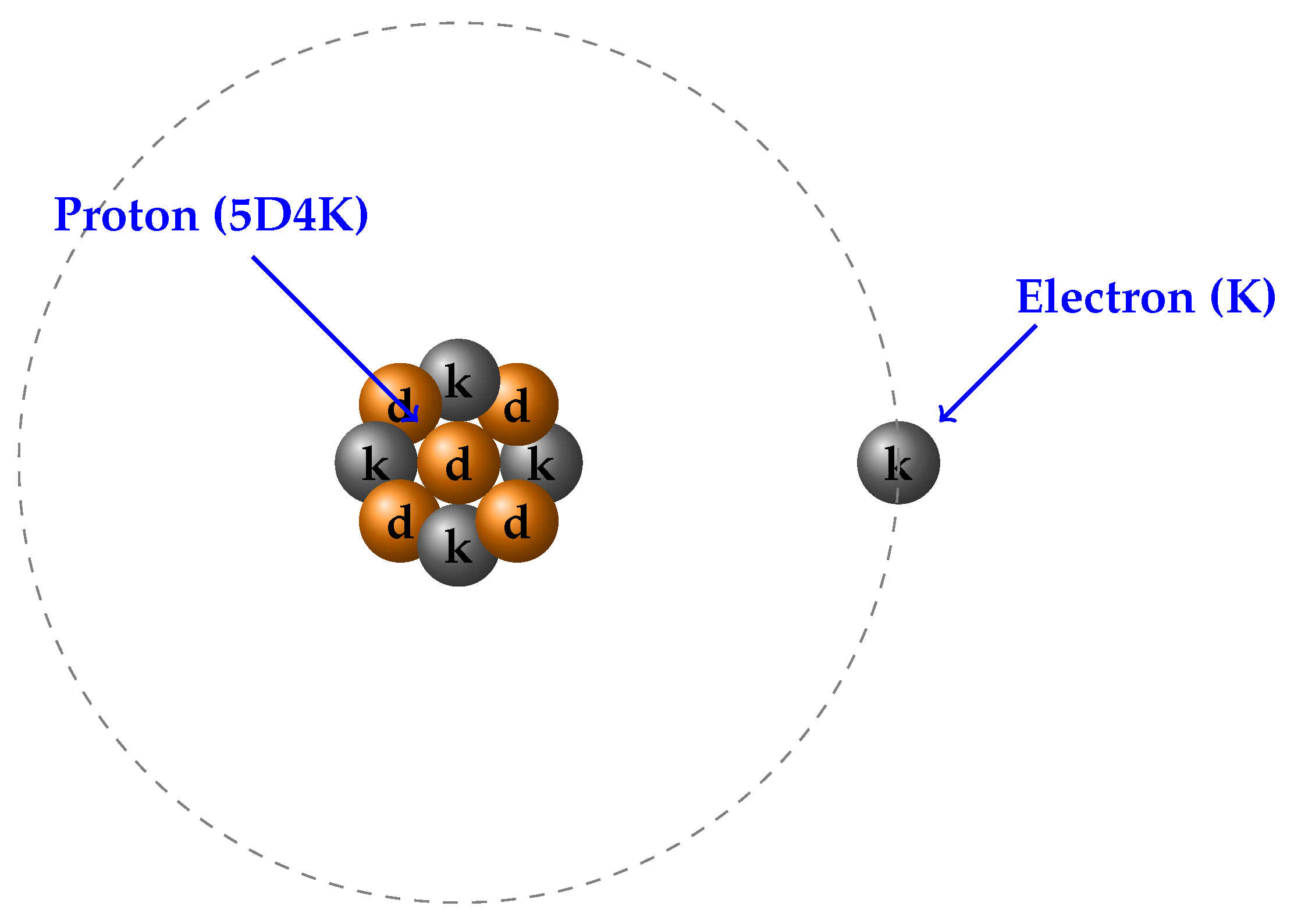

3.8.2. K—D Structure of Particles

Proton: ,

Stable Neutron: ,

Electron: , ,

Photon: , (rest mass), (micro dynamic mass)

3.8.3. Mass Equations

General (Proton, Neutron):

Photon (micro dynamic mass):

3.8.4. Calibrated Constants = Tablet Number 2

Table 2.

Calibrated constants for calculations.

Table 2.

Calibrated constants for calculations.

| Constant |

Value |

SI Unit |

| k |

|

kg·m4·s−2

|

|

|

J |

|

r (nuclear) |

|

m |

|

(electron) |

|

m |

|

|

– |

| c |

|

m·s−1

|

3.8.5. Dimensional Consistency = Table Number 3

Table 3.

Dimensional analysis of equations.

Table 3.

Dimensional analysis of equations.

| No. |

Equation |

LHS |

RHS |

Context |

| 1 |

|

N |

N |

Force |

| 2 |

|

J |

J |

Potential energy |

| 3 |

|

kg |

kg |

Proton/Neutron mass |

| 4 |

|

J |

J |

Total energy |

| 5 |

|

m |

m |

Distance relation |

| 6 |

|

kg |

0 |

Photon rest mass |

| 7 |

|

N |

N |

Interaction |

| 8 |

|

N |

N |

Inertia |

| 9 |

|

– |

– |

Entropy |

| 10 |

|

J |

J |

Photon energy |

| 11 |

|

m/s |

m/s |

Photon speed |

| 12 |

|

kg |

kg |

Electron mass |

3.8.6. Mass Calculations

Electron

Denominator =

Numerator =

Proton

Denominator =

Numerator =

Neutron

(

as in proton)

Photon (micro dynamic mass)

4. Formation and Structure of the Hydrogen Atom

The formation of atoms in this framework emerges naturally from the bonding and aggregation of K and D particles. As new K–D pairs form throughout the universe, their selective attraction allows aggregation into stable atomic structures—most notably, the hydrogen atom.

4.1. K–D Bonding and Hydrogen Structure

Each hydrogen atom, in this model, consists of a core with one additional K particle in an external orbit:

Thus, hydrogen contains a total of 10 fundamental energy particles: .

The attractive force holding the atom together arises from the inverse-cube law:

where

k is the K–D coupling constant, and

r is the separation between the orbiting K particle and the core.

4.2. Stable Arrangement

The core forms due to sequential bonding of K–D pairs.

The fifth K particle (electron analogue) cannot be fully absorbed and is stabilized in an orbital, leading to the quantized structure of atoms.

Fluctuations in cosmic D particle density influence orbital radii, accounting for atomic energy levels.

4.3. Predicted Particle Substructures

The proposed model offers unique and experimentally testable substructures for known particles:

These predictions can be directly validated or refuted by high-energy collision experiments, such as those undertaken with the LHC.

4.4. Significance

Unlike traditional models that rely on abstract quantum fields or spacetime fabric, this approach attributes all atomic structure, binding, and dynamics to direct K–D interactions and geometric configuration, removing the need for additional theoretical constructs or hidden variables.

5. Gravitation and Cosmic Implications

5.1. 1.Unified Explanation of Gravity

In the K–D framework, gravity is not a manifestation of spacetime curvature but arises from the direct attraction between negative-energy K particles and positive-energy D particles. The force law governing this attraction is given by:

where

F is the attractive force,

k is the fundamental K–D coupling constant, and

r is the spatial separation.

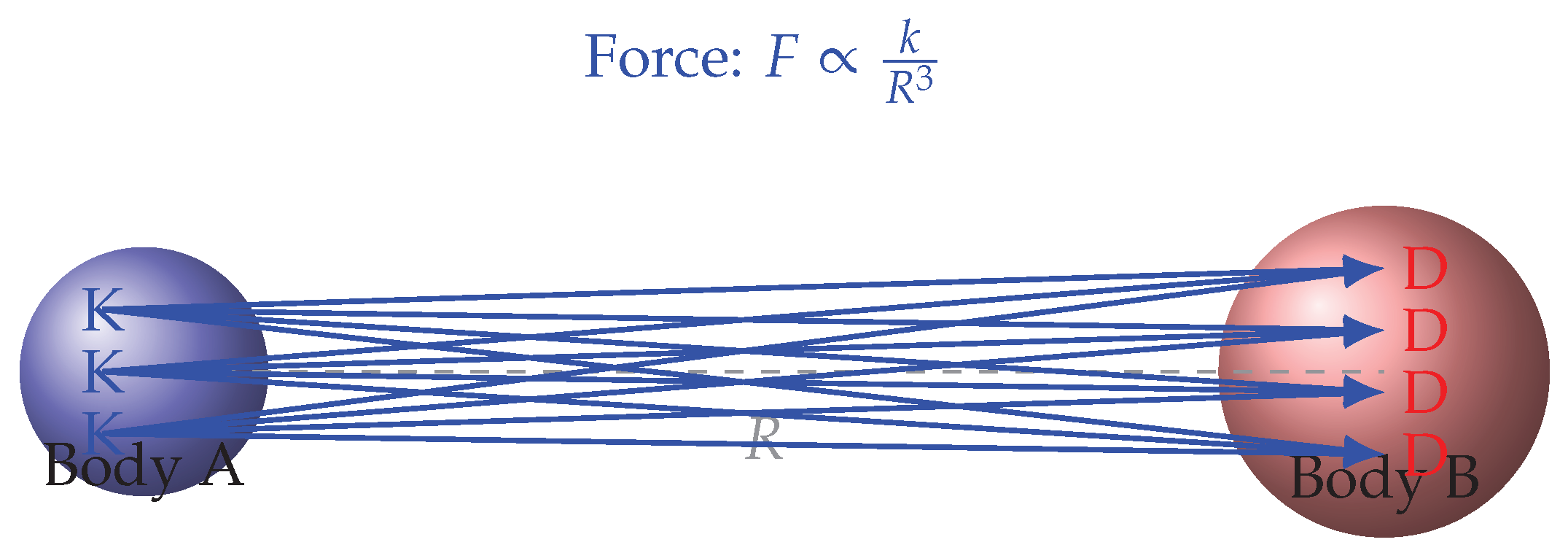

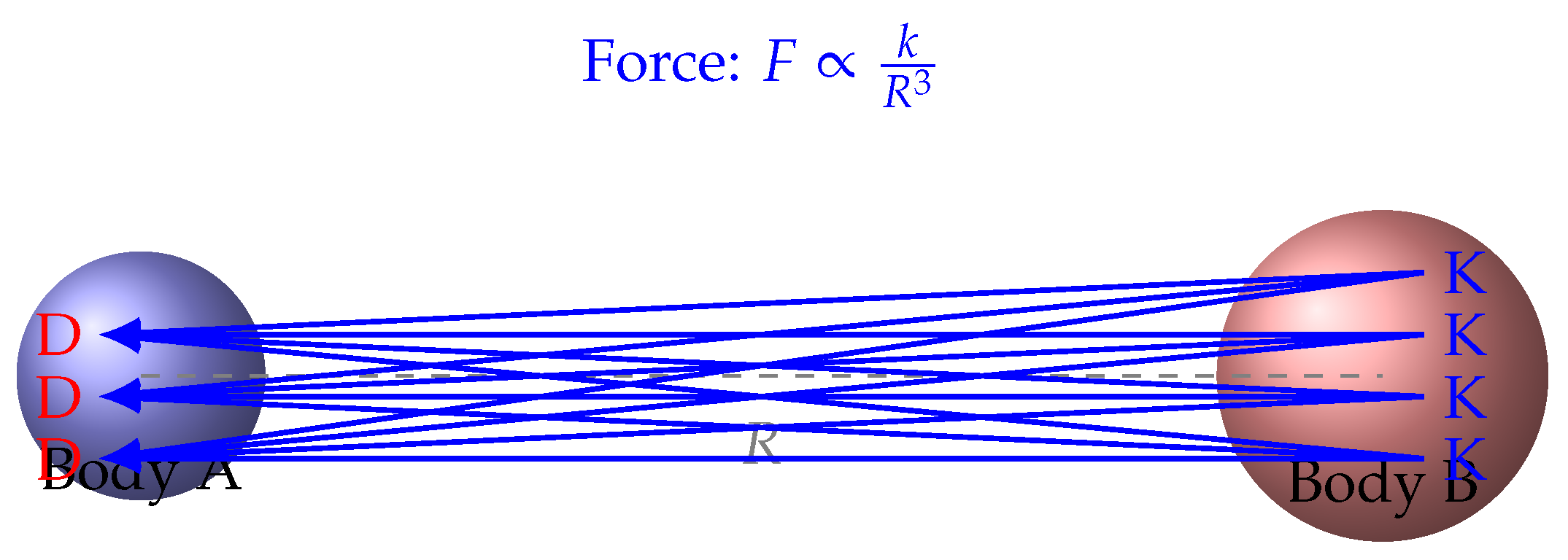

6. Origin of Weight and Large-Scale Structures

In the K–D framework, gravitation between macroscopic bodies—such as planets and stars— emerges as the cumulative effect of microscopic K–D interactions across their constituent particles. Consequently, the total weight of an object and the architecture of cosmic structures depend not solely on its conventional “mass,” but on the density and distribution of K and D particles within it. A higher concentration of K particles enhances internal binding and attraction, while the extreme gravitational strength of black holes is attributed to their exceptionally high K-particle density; photons, being pure D-particle states, cannot escape this attraction.

In contrast to Newtonian physics—where gravitational force and weight were treated as equivalent—our formulation distinguishes between the two. Newton’s law effectively measured weight as a surface-level approximation, without addressing its mechanistic origin. In the K–D theory, weight arises from the mutual interaction of K particles in one body with D particles in another. The fundamental attractive force obeys:

where

F represents the intrinsic K–D coupling force. In comparison, the Newtonian decay of weight is expressed as

Here, F is the true microscopic force of attraction, while W represents the emergent, macroscopic weight—essentially the resultant of two-body K–D interactions.

Figure 1.

Attraction of A’s K particles on B’s D particles.

Figure 1.

Attraction of A’s K particles on B’s D particles.

Figure 2.

Attraction of B’s K particles on A’s D particles.

Figure 2.

Attraction of B’s K particles on A’s D particles.

Figure 3.

Net effect of mutual K–D attractions interpreted by Newton as Weight ().

Figure 3.

Net effect of mutual K–D attractions interpreted by Newton as Weight ().

7. Entropy Asymmetry and Cosmic Balance in the K–D Framework

According to the K–D framework, as the universe expands, new K–D pairs continually originate at the cosmic boundary and stable hydrogen atoms are formed, causing the universe to grow ever larger. At the moment of cosmic origin, when the initial energy unit divided into the first K and D particles, the seed of imbalance was already sown—each K particle in these initial K–D pairs was inherently unbalanced, giving rise to the primordial attractive force. In this early state, the universe was in thermal equilibrium, but a genuine manifestation of imbalance and the disruption of equilibrium truly began with the onset of hydrogen nuclear fusion. It was this fusion event that initiated a definite asymmetry in the number of D and K particles among the stable hydrogen atoms.

When hydrogen fusion occurs, a D particle separates from its paired K particle and moves freely, becoming attracted to all K particles present throughout the universe in an effort to restore balance. As a result, among stable hydrogen atoms in the universe, the ratio of D (positive-energy particles) to K (negative-energy particles) develops a persistent, natural asymmetry, further amplified by fusion events. This can be quantitatively expressed as:

where

denotes the entropy asymmetry, and

D and

K are the numbers of positive- and negative-energy particles, respectively.

Newly synthesized hydrogen atoms do not immediately attain thermal equilibrium; rather, through their constituent K particles, they continually interact with the pre-existing free D particles in the cosmos to achieve balance. This ongoing process of equilibration ensures that the D-to-K ratio never remains fixed, maintaining a global K–D attraction network (cosmic network) throughout the universe. Every new atom and every new particle becomes part of this network, driving both entropy asymmetry and cosmic expansion.

Thus, the K–D framework demonstrates that the observed increase in universal entropy, the arrow of events, and the continuous expansion of the cosmos are not the result of hypothetical dark energy or dark matter, but are instead the direct outcome of primordial K–D asymmetry and their dynamic mutual interactions.

8. Implications and Predictions

8.1. Gravity: Fundamental Particle-Based Force

Gravity arises from the direct attraction between K (negative-energy) and D (positive-energy) particles. The attractive force is inversely proportional to the cube of the distance, fundamentally different from Newton’s and Einstein’s models:

This force depends on the number and interaction of K and D particles at the atomic level. Understanding gravity does not require imaginary concepts like dark matter or spacetime curvature.

8.2. Light and the Resolution of Wave-Particle Duality

Photons are defined as pure D particles, with no binding to K particles and zero rest mass (). The constant speed of photons originates from the universal K particles’ stable attraction field. The wave-like behavior of photons arises from disturbances in this constant speed.

In the double-slit experiment, each photon restores the energy imbalance generated by K and D particles while passing through the slits. Due to this process, photons move in a new direction towards equilibrium, and the shadow of the obstruction between slits appears throughout the pattern.

As a result, light behaves only as a particle, and the concept of wave-particle duality is rejected.

8.3. Mechanical Causes of Cosmological Expansion

The universe expands due to the continuous creation of K–D pairs and the imbalance in their ratio (). This increases the energy imbalance (), which controls the expansion of the universe. From this perspective, imaginary concepts like dark energy become irrelevant.

8.4. Refutation of the Big Bang Singularity

The universe did not originate from a single point or hypothetical inflation, but from the spontaneous division of the fundamental energy field and the creation of K–D pairs. This approach provides a causal, mechanical, and testable perspective.

8.5. Proton and Neutron Structure

These structures determine their mass and charge. High-energy experiments (such as at the LHC) can verify these structures.

8.6. Quantum Entanglement

Quantum entanglement arises from the direct, distance-independent attractive force between K and D particles. It is a purely physical process; information does not travel faster than the speed of light. Bell test experiments can verify this.

8.7. Planetary Spin and Retrograde Rotation

The retrograde spin of Venus is due to the predominance of K particles. Venus’s K particles successfully entangle with the Sun’s D particles, while in other planets, their D particles entangle with the Sun’s K particles.

This prediction can be verified by missions measuring planetary rotation and gravitational fields (e.g., VERITAS, EnVision).

8.8. Mass: Particle-Based Origin

The weight of objects arises from the mutual attraction between the K and D particles of two bodies. If the force decreases as

the weight decreases proportionally as

8.9. Black Hole Properties

The minimum temperature and event freezing of a black hole are determined by the arrangement and balance of K particles. The black hole shadow and other observational signatures are testable via the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and related astronomical observations.

9. Comparison of the K–D Theory with Established Physical Frameworks

9.1. Foundation of Universe Creation

Standard Cosmology (Big Bang Model): The accepted Big Bang model postulates a singular cosmic origin characterized by an initial singularity, followed by inflation and dark energy–driven acceleration. Despite empirical successes such as the cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies and redshift observations, it relies on hypothetical constructs lacking direct experimental verification, such as dark energy and inflationary fields. The initial low-entropy condition and the mechanism for time’s arrow remain open questions.

K–D Theory: Proposes a deterministic origin of the universe from the continuous generation of two fundamental energy particles—K (negative energy) and D (positive energy)—with total conserved energy (). Cosmic expansion and entropy increase naturally emerge from an imbalance ratio (), obviating the need for singularities, dark energy, or inflation. The model offers a mechanistic and testable foundation aligned with observational data, notably bypassing the Big Bang’s initial condition problem.

9.2. Gravitation and Spacetime Structure

Newtonian and Einsteinian Gravity: Newtonian theory describes gravity as a force between masses but does not elucidate its origin. Einstein’s General Relativity reinterprets gravity as spacetime curvature caused by mass–energy, a profound mathematical framework verified by gravitational lensing, perihelion precession, and gravitational waves. However, it remains incompatible with quantum principles and predicts singularities (e.g., black holes), and involves a non-physical spacetime fabric concept.

K–D Theory: Identifies gravitation as a particle interaction phenomenon, arising from inverse-cube force attraction between K and D particles

eliminating reliance on spacetime curvature. Mass emerges from K–D binding energy, offering clarity on inertia and gravitational origin. Black holes correspond to regions of extreme K particle density, resolving singularity and temperature paradoxes without Hawking radiation. The theory reproduces classical gravitational phenomena while providing a unified microscopic explanation compatible with quantum principles.

9.3. Quantum Mechanics and Entanglement

Conventional Quantum Theory: Embraces wave–particle duality, probabilistic interpretations, and non-locality, with quantum entanglement famously described as “spooky action at a distance.” Despite predictive success and experimental validation via Bell tests, it lacks a clear physical mechanism for entanglement and often invokes observer-dependent interpretations.

K–D Theory: Rejects wave–particle duality, defining photons strictly as massless pure D particles (). Wave-like phenomena arise from energy equilibration driven by K particle attraction. Quantum entanglement is explicated as an instantaneous, continuous K–D attractive bond, independent of distance and free from information transfer, reconciling non-local correlations with causality.

9.4. Particle Physics and the Standard Model

Standard Model: Categorizes matter into quarks, leptons, and gauge bosons, with complex interactions mediated by force carriers. While experimentally validated, it requires numerous adjustable parameters and postulated entities like the Higgs boson, dark matter, and dark energy. It does not elucidate the fundamental cause of mass or charge and lacks unification with gravity.

K–D Theory: Simplifies matter composition to just two fundamental energy particles, K and D, explicitly modeling protons as , neutrons as , and electrons as single K particles with effective positive energy influence. Mass and charge derive naturally from particle counts and configurations, eliminating the need for extraneous constructs. This deterministic framework enables direct experimental tests at facilities such as the LHC.

9.5. Light and Electromagnetic Phenomena

Classical and Quantum Electrodynamics: Describe light through electromagnetic waves and photons exhibiting wave–particle duality. The constancy of light speed is postulated, with soft interpretation of its origin, and quantum optics demands probabilistic frameworks.

K–D Theory: Defines photons strictly as unbound D particles with zero rest mass, driven at constant speed

c by universal K particle attraction

Wave phenomena are reinterpreted as energy equilibrium processes without intrinsic wave nature. The speed of light is source-independent and absolute, consistent with experimental observations such as Michelson–Morley and GPS measurements.

9.6. Radioactivity and Nuclear Decay

Traditional Nuclear Physics: Attributes radioactivity to probabilistic weak interactions and particle transformations without clear mechanical explanation of causes for neutron instability or energy emission origin.

K–D Theory: Explains nuclear stability and decay through quantitative imbalances in K and D particle configurations. For example, tritium decay results from D particle emission driven by K–D asymmetry, mechanically tied to universal K attraction. The framework offers predictive capabilities for decay processes that align with observed phenomena.

9.7. Refutation of Non-Physical Constructs

Established Theories: Rely extensively on concepts lacking direct physical entities, including spacetime fabric, dark matter, dark energy, and hypothetical gravitational centers. These introduce complexity and unresolved foundational issues.

K–D Theory: Eliminates non-physical abstractions by rooting all phenomena in concrete K and D particle interactions, providing a coherent, testable, and parsimonious model.

9.8. Summary

The K–D Theory offers a unified physical framework addressing fundamental issues inherent in prevailing models. By reducing the complexity of particle taxonomy, furnishing a mechanistic base for gravity, time, inertia, quantum entanglement, and cosmic expansion, and discarding extraneous assumptions, it represents a paradigm shift in modern physics. The theory’s strong predictive capacity and experimental testability render it a promising candidate for a next-generation unified physical theory.

10. Conclusions

The Absolute Equation of Universe Creation provides a unified, predictive, and testable framework in which all fundamental physical phenomena arise from K–D particle interactions and a single force law. This approach naturally explains the emergence of mass, gravity, light, quantum entanglement, and cosmological evolution, and does so without reliance on theoretical constructs that lack direct physical evidence. With a simple, minimalist foundation and robust experimental predictions, the K–D model stands as a compelling alternative to traditional theories—open to validation or falsification as new data emerge. This could herald a paradigm shift in our understanding of reality at its most fundamental scale.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

The author did not receive any financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information Files.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the use of publicly available experimental data and prior literature in particle physics and cosmology that have informed and supported this research. This work was conducted independently without collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

References

- Meel, K.S.: The Absolute Equation of Universe Creation: A Unified Framework of Reality Based on K–D Particle Interaction (2025).

- Hubble, E. A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1929, 15, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Einstein, A.: The field equations of gravitation. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss., 844–847 (1915).

- Bohr, N. On the constitution of atoms and molecules. Philos. Mag. 1913, 26, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Planck, M. On the law of distribution of energy in the normal spectrum. Ann. Phys. 1900, 4, 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox. Physics 1964, 1, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMS Collaboration. The CMS experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. J. Instrum. 2008, 3, S08004. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W. Black hole explosions? Nature 1974, 248, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1982, 21, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I.: Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Royal Society, London (1687).

- Peebles, P.J.E.: Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1993).

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G. et al.: Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. Astron. J. 116, 1009–1038 (1998).

- Maldacena, J.M. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1999, 38, 1113–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A.: Superspace and the nature of quantum geometrodynamics. In: Battelle Rencontres, pp. 242–307 (1968).

- DESI Collaboration: Early data release and cosmological implications from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument. (2024).

- LUX–ZEPLIN (LZ) Collaboration: New world-leading limits on WIMP Dark Matter from the LZ experiment. JINST (2024).

- Duran, B. et al.: Determining the gluonic gravitational form factors of the proton. Nature 615, 813–816 (2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).