3.2. Effect of Herbivory on Morphological Traits

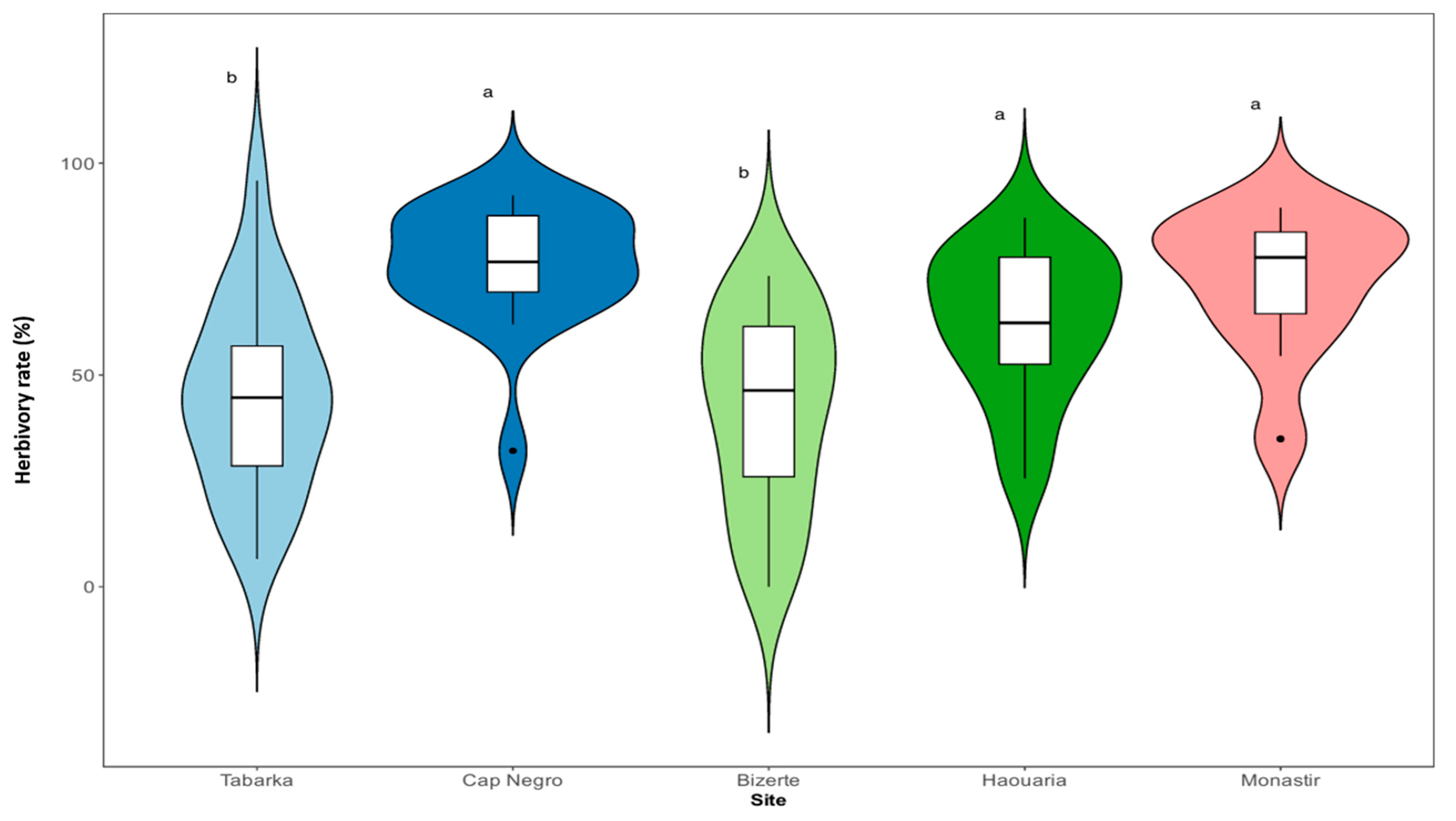

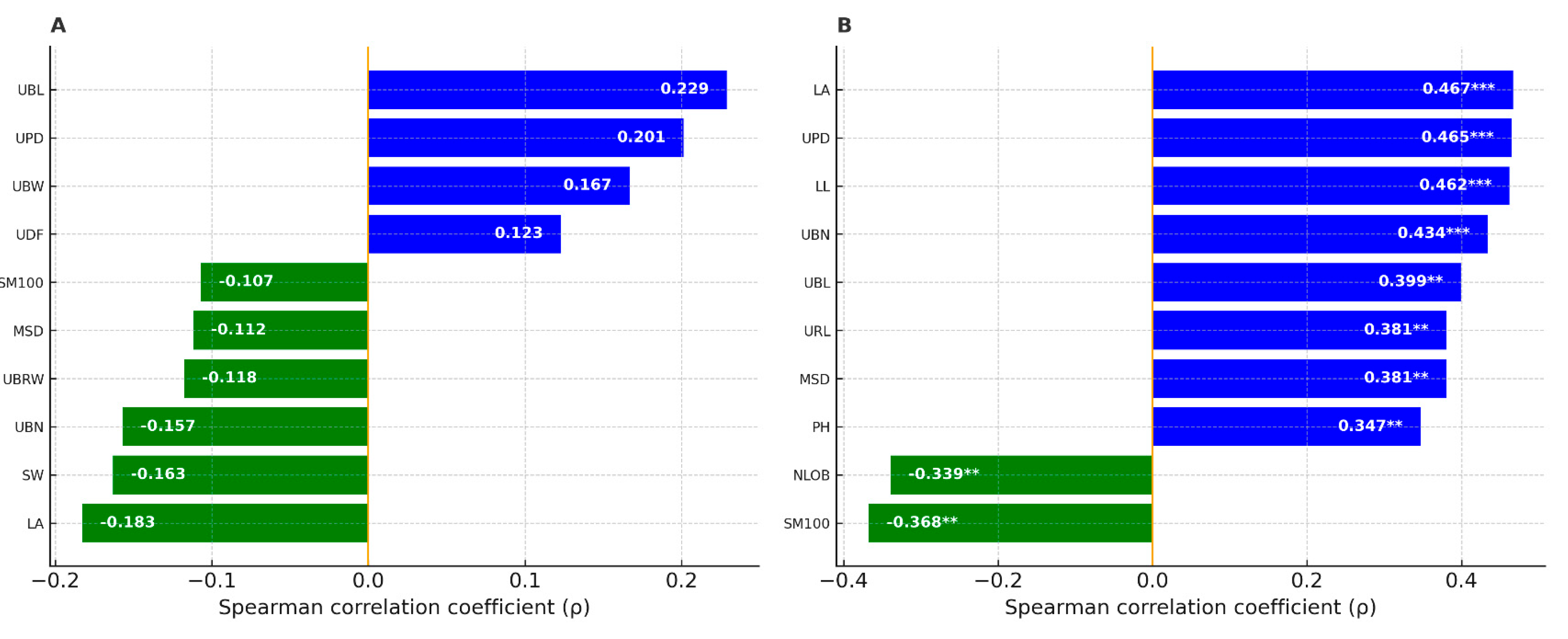

Using the individual-level data, we assessed the association between herbivory intensity—expressed as the number of attacked fruits per plant—and each morphological trait with Spearman’s rank correlations. Analyses were performed separately for low-herbivory sites (Tabarka, Bizerte;

n = 40) and high-herbivory sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir;

n = 60) (

Figure 3).

In low-herbivory sites, no correlation reached significance; the most significant effects were minor, with weak positive tendencies for umbel bract length (UBL; ρ = 0.229, p = 0.156) and peduncle diameter (UPD; ρ = 0.201, p = 0.213), and weak negative tendencies for leaf area (LA; ρ = −0.183, p = 0.259) and seed width (SW; ρ ≈ −0.163, p > 0.30). In high-herbivory sites, several traits correlated significantly with herbivory. The number of attacked fruits increased with leaf size and more robust inflorescence structures, including LA (ρ = 0.467, p = 1.7 × 10⁻⁴***), UPD (ρ = 0.465, p = 1.8 × 10⁻⁴***), leaf length LL (ρ = 0.462, p = 2.0 × 10⁻⁴***), the number of umbel bracts UBN (ρ = 0.434, p = 5.3 × 10⁻⁴***), as well as UBL (ρ = 0.399, p = 0.0016), ray length URL (ρ = 0.381, p = 0.0027), main stem diameter MSD (ρ = 0.381, p = 0.0027), plant height PH (ρ = 0.347, p = 0.0066), leaf width LW (ρ = 0.339, p = 0.0081) and the number of umbellet bracteoles UNBR (ρ = 0.333, p = 0.0093). In this context, two traits were negatively associated with herbivory: 100-seed weight SM100 (ρ = −0.368, p = 0.0039) and the number of leaf lobes NLOB (ρ = −0.339, p = 0.0081). Overall, the absence of detectable associations under low herbivory and the emergence of multiple moderate correlations under high herbivory indicate a context-dependent coupling between plant architecture and herbivore damage.

3.3. Effect of Herbivory on Biochemical Traits

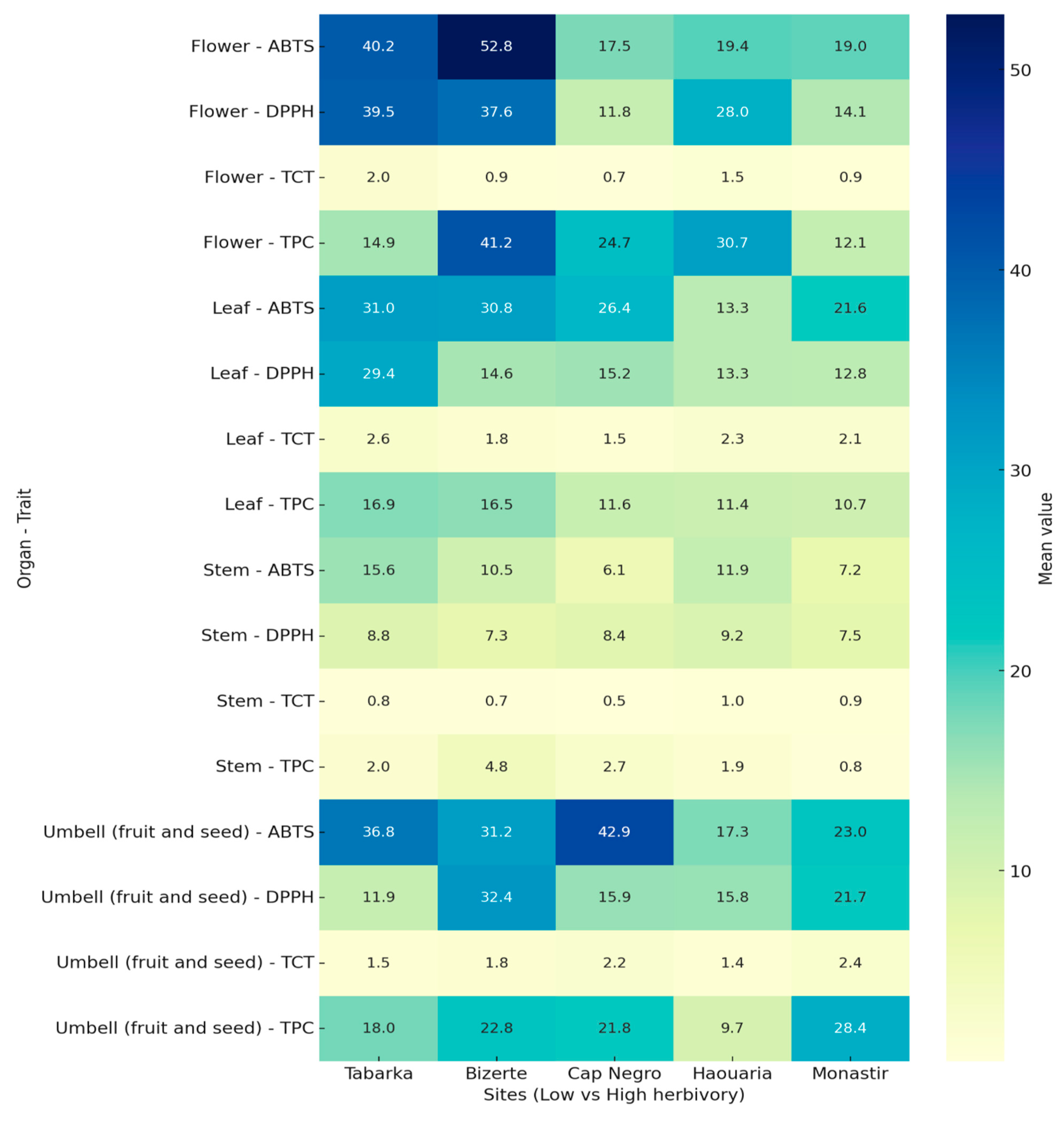

Biochemical traits were quantified in four organs (Leaf, Flower, Stem, Umbell) across Low (Tabarka, Bizerte) and High herbivory sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir). Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4) and are summarized in

Table 4a and 4b.

In the Low herbivory group, leaves exhibited TPC values ranging from 14.08 ± 2.72 to 19.92 ± 2.00 mg GAE/g DW, while ABTS activities varied between 23.99 ± 3.00 and 39.72 ± 2.10 µmol TE/g DW. Flowers displayed higher TPC, reaching 44.67 ± 0.77 mg GAE/g DW in Bizerte, while umbels showed moderate levels, ranging from 14.92 ± 1.80 to 25.25 ± 2.10 mg GAE/g DW. Stems had the lowest values overall, with TPC between 1.25 ± 0.52 and 5.75 ± 0.83 mg GAE/g DW.

In the High herbivory group, leaves had lower phenolic contents, ranging from 9.17 ± 2.27 to 13.50 ± 1.21 mg GAE/g DW, with ABTS values between 11.49 ± 1.90 and 28.66 ± 2.30 µmol TE/g DW. Flowers were highly variable, from 12.00 ± 0.17 mg GAE/g DW in Monastir to 40.50 ± 1.53 mg GAE/g DW in Haouaria. Umbels showed the broadest range of values, from 8.42 ± 1.54 mg GAE/g DW in Haouaria to 36.25 ± 3.73 mg GAE/g DW in Monastir. Stem extracts consistently displayed the lowest activities, with TPC < 4.0 mg GAE/g DW and antioxidant capacities (DPPH, ABTS) < 16 µmol TE/g DW.

Figure 4 shows a global comparison of biochemical profiles across organs and sites, with Low sites (Tabarka, Bizerte) contrasted with High sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir).

The heatmap shows distinct differences in biochemical profiles between Low and High herbivory sites. In the Low group (Tabarka, Bizerte), flowers and umbels generally had higher phenolic and antioxidant levels than stems, which consistently recorded the lowest values across all traits.

In the High herbivory group (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir), significant site-dependent differences were observed. Haouaria flowers showed the highest TPC values, while Monastir umbels recorded the highest phenolic contents and antioxidant activities (TPC, ABTS). Conversely, Haouaria umbels displayed the lowest phenolic and antioxidant levels among the High sites. Stems remained the least active organs across all sites.

The heatmap highlights that reproductive organs (flowers and umbels) are the most variable across sites, while stems consistently show low biochemical values regardless of herbivory levels.

Building on these biochemical patterns, we next examined the mineral composition of C. maritimum organs across the five sites to determine whether macro- and micro-element profiles also differed between populations exposed to low versus high herbivory pressure.

Table 4a.

Biochemical traits (mean ± SD, n = 4) for four organs (Leaf, Flower, Stem, Umbell) in Low herbivory sites (Tabarka, Bizerte).

Table 4a.

Biochemical traits (mean ± SD, n = 4) for four organs (Leaf, Flower, Stem, Umbell) in Low herbivory sites (Tabarka, Bizerte).

| Organ |

Trait |

Tabarka |

Bizerte |

| Leaf |

TPC |

16.85 ± 2.04 |

16.48 ± 2.34 |

| |

TCT |

2.57 ± 0.31 |

1.76 ± 0.38 |

| |

DPPH |

29.37 ± 2.51 |

14.59 ± 0.22 |

| |

ABTS |

31.01 ± 6.64 |

30.82 ± 4.74 |

| Flower |

TPC |

14.92 ± 2.39 |

41.23 ± 3.72 |

| |

TCT |

2.01 ± 0.53 |

0.90 ± 0.14 |

| |

DPPH |

39.53 ± 3.05 |

37.56 ± 1.32 |

| |

ABTS |

40.23 ± 0.87 |

52.77 ± 1.76 |

| Stem |

TPC |

2.04 ± 1.21 |

4.79 ± 0.65 |

| |

TCT |

0.77 ± 0.24 |

0.69 ± 0.28 |

| |

DPPH |

8.83 ± 0.42 |

7.26 ± 1.69 |

| |

ABTS |

15.56 ± 0.71 |

10.53 ± 2.27 |

| Umbell |

TPC |

18.00 ± 2.47 |

22.83 ± 1.65 |

| |

TCT |

1.48 ± 0.34 |

1.75 ± 0.46 |

| |

DPPH |

11.86 ± 0.38 |

32.44 ± 2.56 |

| |

ABTS |

36.77 ± 3.95 |

31.18 ± 4.29 |

Table 4b.

Biochemical traits (mean ± SD, n = 4) for four organs (Leaf, Flower, Stem, Umbell) in High herbivory sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir).

Table 4b.

Biochemical traits (mean ± SD, n = 4) for four organs (Leaf, Flower, Stem, Umbell) in High herbivory sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir).

| Organ |

Trait |

Cap Negro |

Haouaria |

Monastir |

| Leaf |

TPC |

11.62 ± 1.88 |

11.38 ± 1.28 |

10.71 ± 1.18 |

| |

TCT |

1.49 ± 0.34 |

2.28 ± 0.32 |

2.14 ± 0.19 |

| |

DPPH |

15.20 ± 0.86 |

13.28 ± 0.86 |

12.83 ± 0.72 |

| |

ABTS |

26.44 ± 1.56 |

13.34 ± 1.75 |

21.62 ± 2.90 |

| Flower |

TPC |

24.73 ± 4.04 |

30.71 ± 6.55 |

12.10 ± 0.12 |

| |

TCT |

0.68 ± 0.48 |

1.53 ± 0.60 |

0.94 ± 1.30 |

| |

DPPH |

11.75 ± 0.99 |

28.03 ± 0.32 |

14.10 ± 0.75 |

| |

ABTS |

17.50 ± 17.74 |

19.43 ± 2.77 |

18.98 ± 0.80 |

| Stem |

TPC |

2.67 ± 1.22 |

1.90 ± 0.49 |

0.83 ± 0.62 |

| |

TCT |

0.47 ± 0.16 |

1.00 ± 0.28 |

0.95 ± 0.10 |

| |

DPPH |

8.41 ± 0.62 |

9.21 ± 0.65 |

7.46 ± 2.44 |

| |

ABTS |

6.13 ± 0.61 |

11.92 ± 0.75 |

7.20 ± 0.85 |

| Umbell |

TPC |

21.81 ± 7.72 |

9.67 ± 1.22 |

28.35 ± 6.33 |

| |

TCT |

2.24 ± 1.68 |

1.41 ± 0.40 |

2.42 ± 1.06 |

| |

DPPH |

15.90 ± 0.15 |

15.77 ± 0.62 |

21.73 ± 1.81 |

| |

ABTS |

42.90 ± 10.46 |

17.29 ± 2.72 |

22.97 ± 1.11 |

3.4. Effect of Herbivory on Mineral Composition:

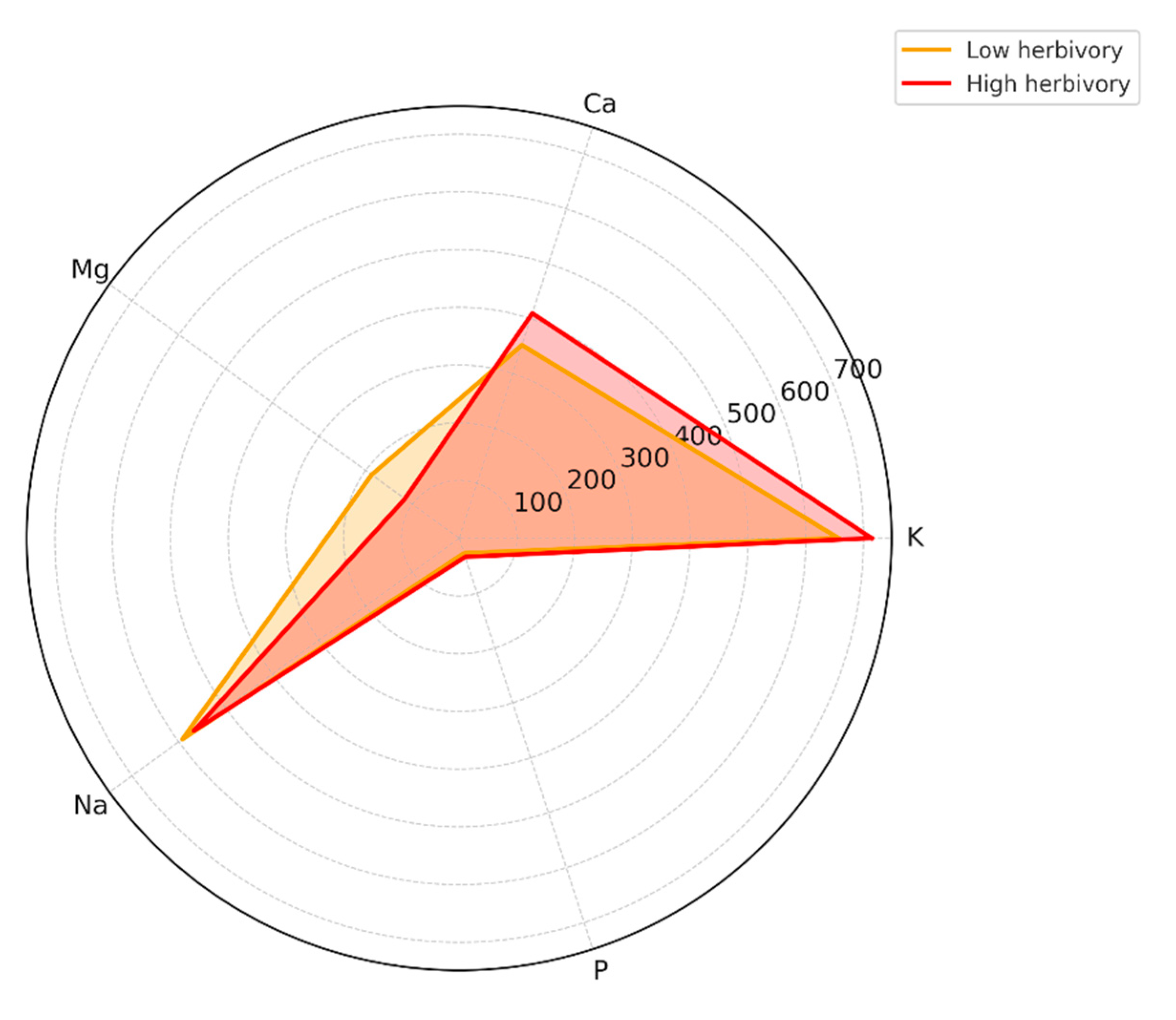

The mineral composition analysis revealed apparent differences among

C. maritimum organs and between populations subjected to low versus high herbivory pressure (

Table 5a and 5b). Potassium was the most abundant element in low-herbivory sites (Tabarka, Bizerte), reaching 890.6 mg·g⁻¹ DW in umbels from Tabarka. Calcium and magnesium were also consistently high in leaves and stems, with Tabarka leaves containing up to 515.2 mg·g⁻¹ DW Ca and stems reaching 515.2 mg·g⁻¹ DW Mg.

On the other hand, populations exposed to high herbivory (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir) showed increased levels of phosphorus and sodium, especially in reproductive organs. For example, umbels from Monastir had 65.8 mg·g⁻¹ DW P and 623.1 mg·g⁻¹ DW Na, significantly higher than those found in populations with low herbivory.

Trace elements involved in plant defense, such as iron, zinc, manganese, and copper, also varied depending on the site. Iron concentrations were highest in flowers from Cap Negro (9.8 mg·g⁻¹ DW), while zinc and manganese were more abundant in Tabarka leaves (0.46 mg·g⁻¹ DW Zn and 0.21 mg·g⁻¹ DW Mn).

Table 5a.

Mineral composition (mg·g⁻¹ DW) of C. maritimum organs from low-herbivory sites (Tabarka and Bizerte).

Table 5a.

Mineral composition (mg·g⁻¹ DW) of C. maritimum organs from low-herbivory sites (Tabarka and Bizerte).

| Site |

Organ |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

P |

Na |

Fe |

Zn |

Mn |

Cu |

| Tabarka |

Flower |

619,74 |

509,29 |

97,11 |

15,08 |

616,61 |

4,68 |

0,42 |

0,23 |

0,09 |

| |

Leaf |

577,59 |

515,25 |

515,25 |

19,2 |

513,9 |

4,13 |

0,46 |

0,21 |

0,06 |

| |

Stem |

784,99 |

227,32 |

68,55 |

21,72 |

579,6 |

2,2 |

0,48 |

0,07 |

0,08 |

| |

Umbell |

890,63 |

392,22 |

99,83 |

41,08 |

623,06 |

3,21 |

0,46 |

0,17 |

0,13 |

| Bizerte |

Flower |

404,15 |

271,27 |

109,13 |

35,8 |

194,32 |

3,9 |

0,46 |

0,31 |

0,11 |

| |

Leaf |

503,45 |

413 |

413 |

14,66 |

857,63 |

8,79 |

0,46 |

0,36 |

0,06 |

| |

Stem |

746,75 |

221,77 |

76,71 |

33,01 |

682,84 |

2,33 |

0,29 |

0,2 |

0,1 |

| |

Umbell |

727,05 |

263,67 |

118,53 |

38,37 |

669,65 |

4,22 |

0,44 |

0,4 |

0,14 |

Table 5b.

Mineral composition (mg·g⁻¹ DW) of C.maritimum organs from high-herbivory sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, and Monastir).

Table 5b.

Mineral composition (mg·g⁻¹ DW) of C.maritimum organs from high-herbivory sites (Cap Negro, Haouaria, and Monastir).

| Site |

Organ |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

P |

Na |

Fe |

Zn |

Mn |

Cu |

| Cap Negro |

Flower |

872,77 |

433,85 |

52,35 |

52,75 |

444,41 |

3,97 |

0,73 |

0,32 |

0,19 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Leaf |

887,93 |

542,37 |

542,37 |

64,69 |

541,61 |

9,84 |

0,62 |

0,42 |

0,15 |

| |

Stem |

773,94 |

270,63 |

24,78 |

19,55 |

780,54 |

1,45 |

0,31 |

0,1 |

0,08 |

| |

Umbell |

514,09 |

411,52 |

133,24 |

39,45 |

372,65 |

9,58 |

0,51 |

0,42 |

0,16 |

| Haouaria |

Flower |

686,87 |

340,86 |

76,39 |

34,86 |

468,28 |

7,51 |

0,49 |

0,6 |

0,16 |

| |

Leaf |

607,9 |

574,42 |

133,02 |

28,5 |

937,28 |

17,76 |

0,54 |

0,91 |

0,17 |

| |

Stem |

710,83 |

314,19 |

83,34 |

16,65 |

557,72 |

9,66 |

0,41 |

0,35 |

0,13 |

| |

Umbell |

774,38 |

357,52 |

94,52 |

27,54 |

433,41 |

19,74 |

0,5 |

0,39 |

0,19 |

| Monastir |

Flower |

492,99 |

646,17 |

68,65 |

32,47 |

446,46 |

7,38 |

0,29 |

0,29 |

0,06 |

| |

Leaf |

835,06 |

335,05 |

74,99 |

28,58 |

941,51 |

3,66 |

0,5 |

0,22 |

0,11 |

| |

Stem |

716,86 |

291,35 |

45,2 |

32,46 |

344,67 |

1,32 |

0,33 |

0,08 |

0,1 |

| |

Umbell |

695,84 |

399,72 |

65,01 |

31,11 |

542,27 |

3,48 |

0,59 |

0,23 |

0,17 |

Overall, the patterns are illustrated in

Figure 5.

Following the mineral composition analysis, we investigated the lipophilic fraction (GC–MS) to evaluate whether herbivory pressure modulates fatty acids, sterols, terpenes, and phenylpropanoids.

3.5. Effect of Herbivory on Lipophilic Fraction (GC–MS)

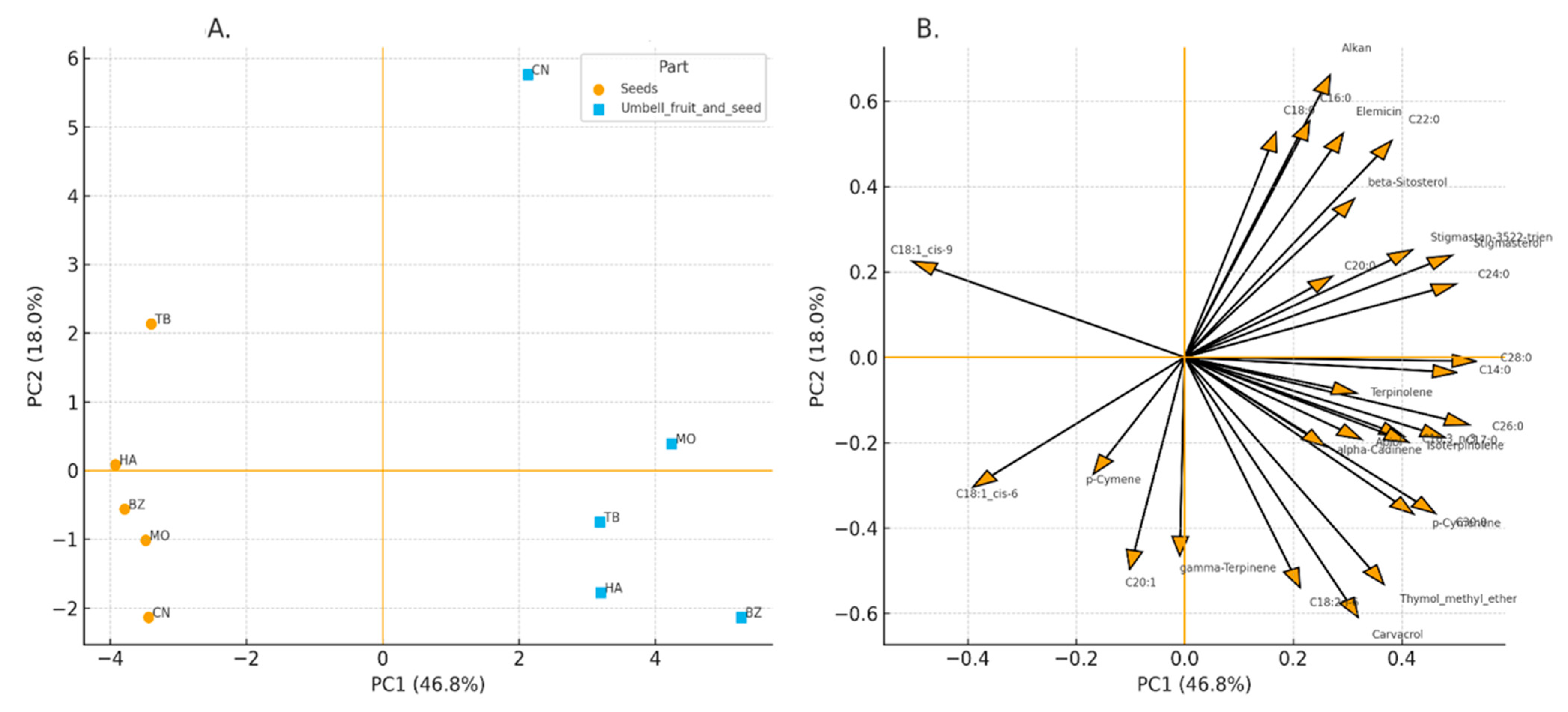

The GC–MS profiling revealed site- and organ-specific signatures further structured by herbivory level. The PCA scores plot (

Figure 6A) separated low-herbivory sites (Tabarka, Bizerte) from high-herbivory populations (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir), with seeds and umbels forming distinguishable clusters within each group. The first two principal components explained 46.8% (PC1) and 18.0% (PC2) of the total variance. The loadings (

Figure 6B) indicated that separation along PC1 was mainly associated with sterols (β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, stigmastan-3,5,22-trien) and terpenes (γ-terpinene, terpinolene, p-cymene/p-cymenene, isoterpinolene), whereas PC2 was driven by saturated fatty acids (C14:0, C16:0, C17:0, C18:0) and apiol.

To statistically validate the patterns observed in the PCA, we next compared the relative abundances of the main lipophilic classes (SFA, MUFA, PUFA, sterols, terpenes, and apiol) among sites using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

The ANOVA confirmed significant differences among sites for apiol, while sterols and terpenes showed less pronounced variation (

Table 6). Apiol exhibited the most significant site-dependent variation, with Monastir recording the highest proportion (17.42 ± 0.45%), significantly higher than Cap Negro (5.85 ± 2.21%) and Haouaria (6.78 ± 8.04%). Tabarka (9.44 ± 8.10%) and Bizerte (7.99 ± 4.05%) had intermediate levels.

In contrast, sterols were more common in low-herbivory sites (Bizerte, Tabarka; average ~1.50%) than in high-herbivory populations (Monastir, Haouaria, Cap Negro; ~1.30%), although the differences were more minor. Terpenes showed some variation, with the lowest at Cap Negro (0.14 ± 0.12%) and the highest at Monastir (0.79 ± 1.05%).

When grouping populations by herbivory level, apiol was generally more abundant in high-herbivory sites (average 10.7%) than low-herbivory ones (8.7%), highlighting its potential role as a defensive metabolite. In contrast, sterols and PUFA were decreased in high-herbivory groups (1.91% and 0.08%, respectively) compared to low-herbivory groups (2.55% and 0.14%), indicating a shift in lipid metabolism under insect pressure. Terpenes showed a slight increase in high-herbivory sites (1.32% vs 1.11% in low), consistent with their function in volatile-mediated defense.

Together, these results show that apiol, sterols, and PUFA are the main lipophilic traits affected by herbivory pressure, aligning with the organ- and site-level patterns found by PCA.

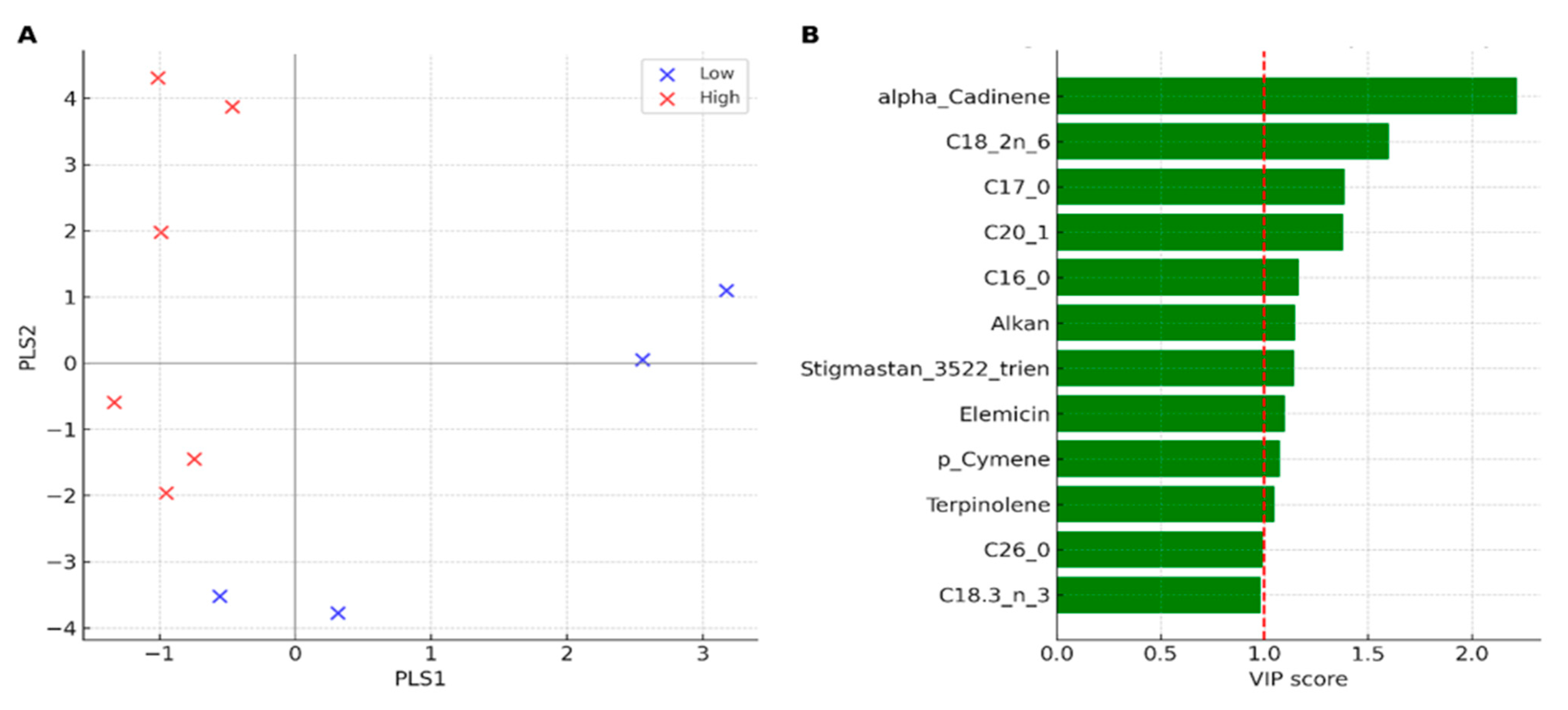

To further verify the difference between low- and high-herbivory populations, we used Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), a supervised technique often employed in metabolomics. This method identifies the compounds that most influence the separation between groups using Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores.

The PLS-DA clearly separated low-herbivory (Tabarka, Bizerte) and high-herbivory populations (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir) along the first two components (

Figure 7A), confirming the grouping previously observed in the PCA (

Figure 6A). The supervised model highlighted the strong contribution of specific compounds to discrimination. VIP scores identified apiol (VIP = 1.72), β-sitosterol (VIP = 1.55), stigmasterol (VIP = 1.41), and the saturated fatty acid palmitic acid (C16:0, VIP = 1.33) as the main variables that distinguish groups, along with minor contributions from terpenes such as terpinolene (VIP = 1.22) (

Figure 7B). Overall, apiol emerged as the most influential metabolite in separating high-herbivory populations, while sterols and SFA contributed to distinguishing low-herbivory groups. This supervised analysis reinforces the patterns both PCA and ANOVA revealed, providing strong evidence that insect pressure heavily influences lipophilic traits.

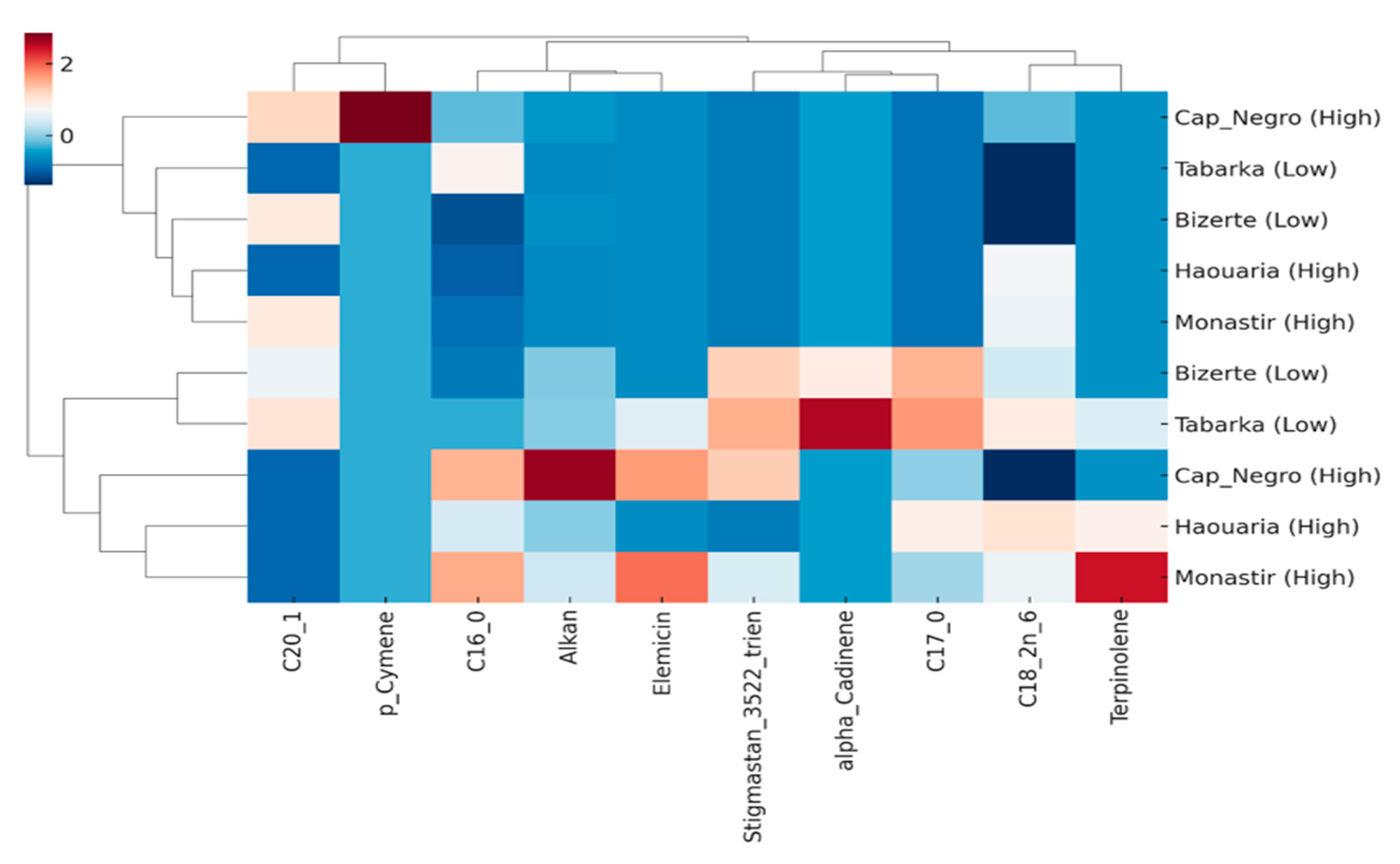

To further visualize how discriminant lipophilic compounds group populations according to herbivory level, a hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) combined with a heatmap was performed using the top variables identified by PLS-DA (VIP > 1.0)

The heatmap and hierarchical clustering clearly distinguished low-herbivory sites (Tabarka, Bizerte) from high-herbivory populations (Cap Negro, Haouaria, Monastir) based on the abundance of discriminant compounds (

Figure 8). The clustering dendrogram grouped the two low-herbivory sites, while Monastir was separated within the high-herbivory group, reflecting its particularly high apiol and terpene contents.

At the compound level, α-cadinene and linoleic acid (C18:2 n-6) were strongly linked to high-herbivory areas, while sterols (stigmastan-3,5,22-trien) and palmitic acid (C16:0) were more common in low-herbivory populations. Elemicin, p-cymene, and terpinolene showed intermediate levels, contributing to subtle differences among high-herbivory sites.

This clustering pattern supports the results of PCA, ANOVA, and PLS-DA, confirming that lipophilic traits are consistently shaped by herbivory pressure and that apiol and specific terpenes are key indicators of high herbivory.

Given the transparent climatic gradient among the study sites, we incorporated bioclimatic factors—specifically, mean annual precipitation and bioclimatic tier—into a multivariate analysis that combines morphological, biochemical, mineral, and lipophilic traits.

3.6. Integrative Analysis of Herbivory-Related Traits and Bioclimatic Context

The integrative analysis combining morphological, biochemical, mineral, and lipophilic traits with bioclimatic parameters offered a comprehensive view of the factors driving trait variability across

C. maritimum populations (

Figure 9).

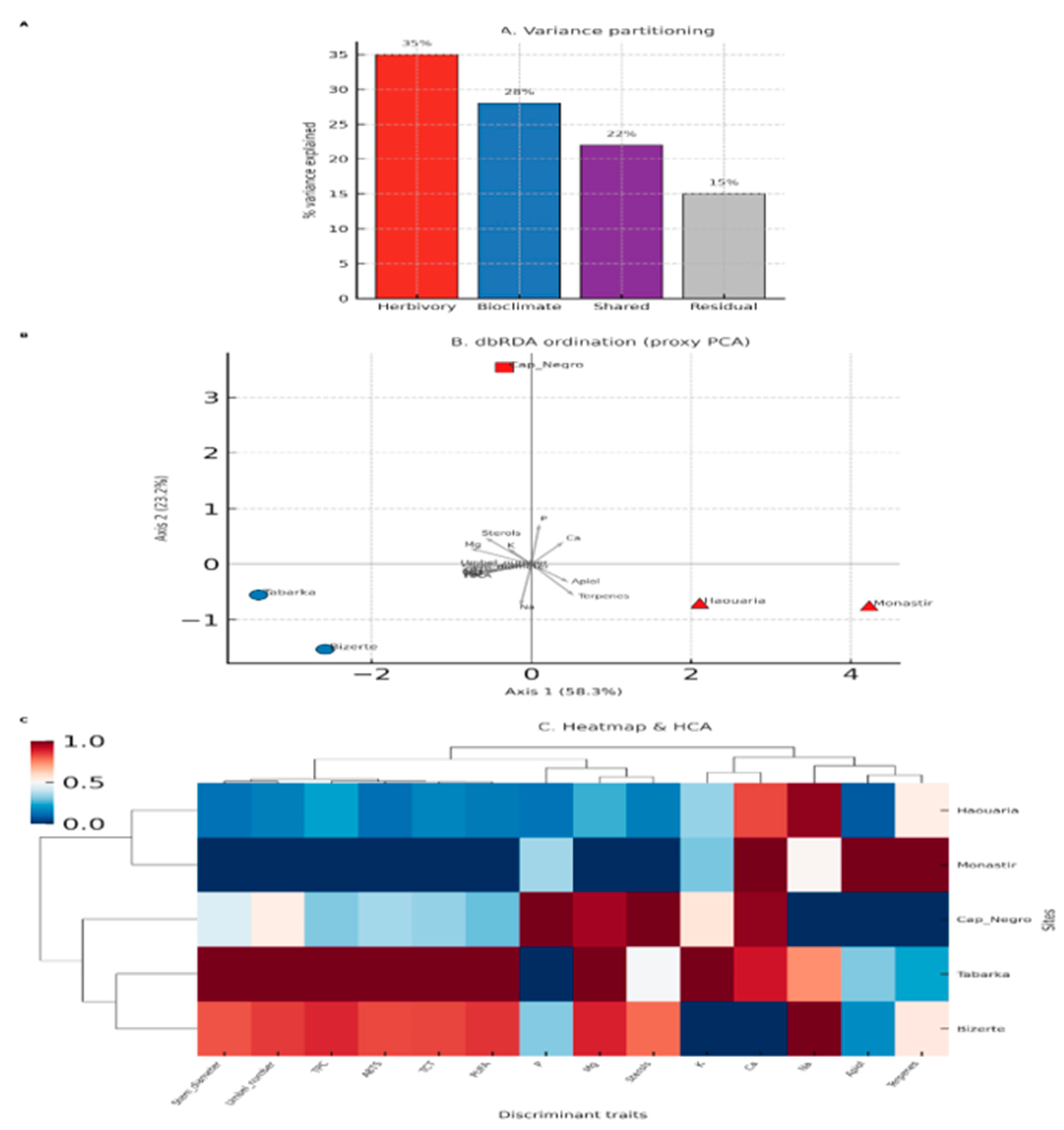

Variance partitioning (

Figure 9A) showed that herbivory pressure alone explained 35% of the observed variance, while the bioclimatic tier (sub-humid, transitional, semi-arid) accounted for 28%. Their shared contribution comprised 22%, and the remaining variance was limited to 15%. These results demonstrate that both herbivory and climate are strong, partly overlapping factors shaping the defense syndromes of

C. maritimum.

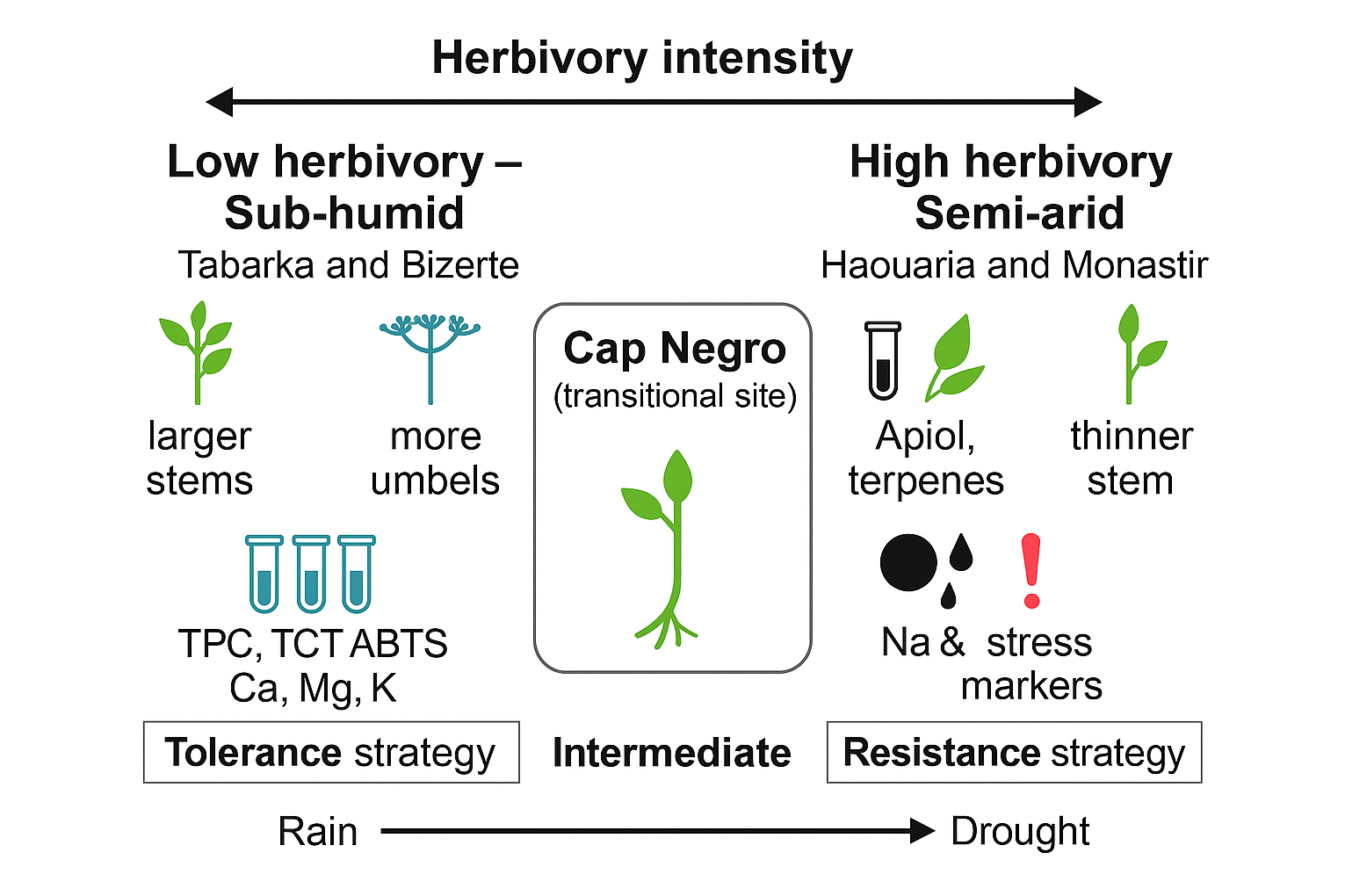

The dbRDA ordination (

Figure 9B) further highlighted a clear separation of sites based on herbivory and climate. Populations from low-herbivory, sub-humid sites (Tabarka and Bizerte) clustered together and were characterized by higher levels of structural traits (stem diameter, number of umbels), biochemical antioxidants (TPC, TCT, ABTS), and mineral nutrients (Ca, Mg, K), as well as sterols and PUFA. In contrast, high-herbivory, semi-arid sites (Haouaria and Monastir) grouped and were strongly associated with increased levels of Apiol and terpenes, along with higher Na and P levels, which contrasted with their lower Ca and Mg contents. These opposing trait patterns reflect two strategies: a tolerance strategy in sub-humid, low-herbivory populations versus a resistance strategy in semi-arid, high-herbivory populations.

The heatmap and hierarchical clustering (

Figure 9C) supported these patterns by consistently distinguishing low-herbivory sub-humid populations (Tabarka, Bizerte) from high-herbivory semi-arid populations (Haouaria, Monastir). Interestingly, despite being categorized in this group, Cap Negro did not cluster tightly with the high-herbivory group. Instead, it occupied an intermediate position, reflecting its transitional bioclimatic conditions and mixed trait profile.

Specifically, Cap Negro showed moderate levels of Ca and Mg, intermediate Apiol and terpenes, and increased but not extreme Na and P, placing it between the two defense syndromes. This intermediate position emphasizes the herbivory responses' gradual and flexible nature, showing that C. maritimum does not follow a strict Low/High dichotomy but demonstrates adaptive flexibility along climatic and herbivory gradients.

Together, these integrative results reinforce the findings from previous sections (1.2–1.5) and show that C. maritimum populations use two distinct but complementary defense strategies, influenced by both herbivory intensity and bioclimatic conditions. This offers a solid framework for understanding herbivory-related trait syndromes' ecological and adaptive importance in coastal halophytes.

These integrative patterns form the cornerstone for interpreting how C. maritimum balances tolerance and resistance strategies under varying ecological pressures. The following discussion will contextualize these findings within the broader framework of plant defense theory and halophyte adaptation in Mediterranean ecosystems.