1. Introduction

Environmental pollution has steadily increased since the start of industrialisation, driven by activities such as power generation, waste disposal, and farming [

1]. This has degraded air quality, polluted water sources, and damaged natural resources. As a result, the impact extends beyond ecosystems, contributing to a global public health crisis responsible for millions of deaths annually [

2]. Increasing environmental pollution and greenhouse gas emissions are causing changes in the climate and contributing to a rise in global warming. The 2015 Paris Agreement sets a target to limit warming to well below 2 °C, preferably 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels [

3]. Achieving this target will require a substantial reduction in the use of fossil fuels and a rapid shift towards bioresources and sustainable products, along with major transformations in global energy systems, industry, and agriculture. Using renewable and sustainable materials, combined with reducing waste during production and consumption, is essential to minimising global warming.

Historically, the term “biomaterials” referred primarily to materials used in medical applications, such as implants, prosthetics, and tissue engineering [

4]. However, the definition has since broadened to include materials that originate from biological sources, are produced through biological processes, or are engineered to interact with biological systems. These materials may be derived from organisms such as plants, bacteria, fungi, or animals, or they may be synthetically produced. Beyond healthcare, biomaterials are now increasingly applied in sustainable manufacturing, bio-based production, and environmental technologies.

As the human population grows, consumption increases, which leads to a rising generation of waste. Consequently, there is a growing availability of bioresources mainly from waste produced by various sources. For example, agricultural waste includes crop residues, fruit and vegetable scraps, animal manure, and pruning materials. Municipal waste consists of household organic waste, yard trimmings, sewage sludge, paper, and biodegradable packaging. Industrial non-fossil waste comes from food processing, textile manufacturing, pulp and paper production, breweries, and herb processing. Forestry and aquaculture waste involves wood residues, sawdust, fish by-products, and seaweed trimmings. Additionally, other sources include natural and marine biomass, construction wood waste, compost, and algae. This variety of waste highlights the potential opportunities to produce valuable biomaterials by recovering bioresources from diverse sectors.

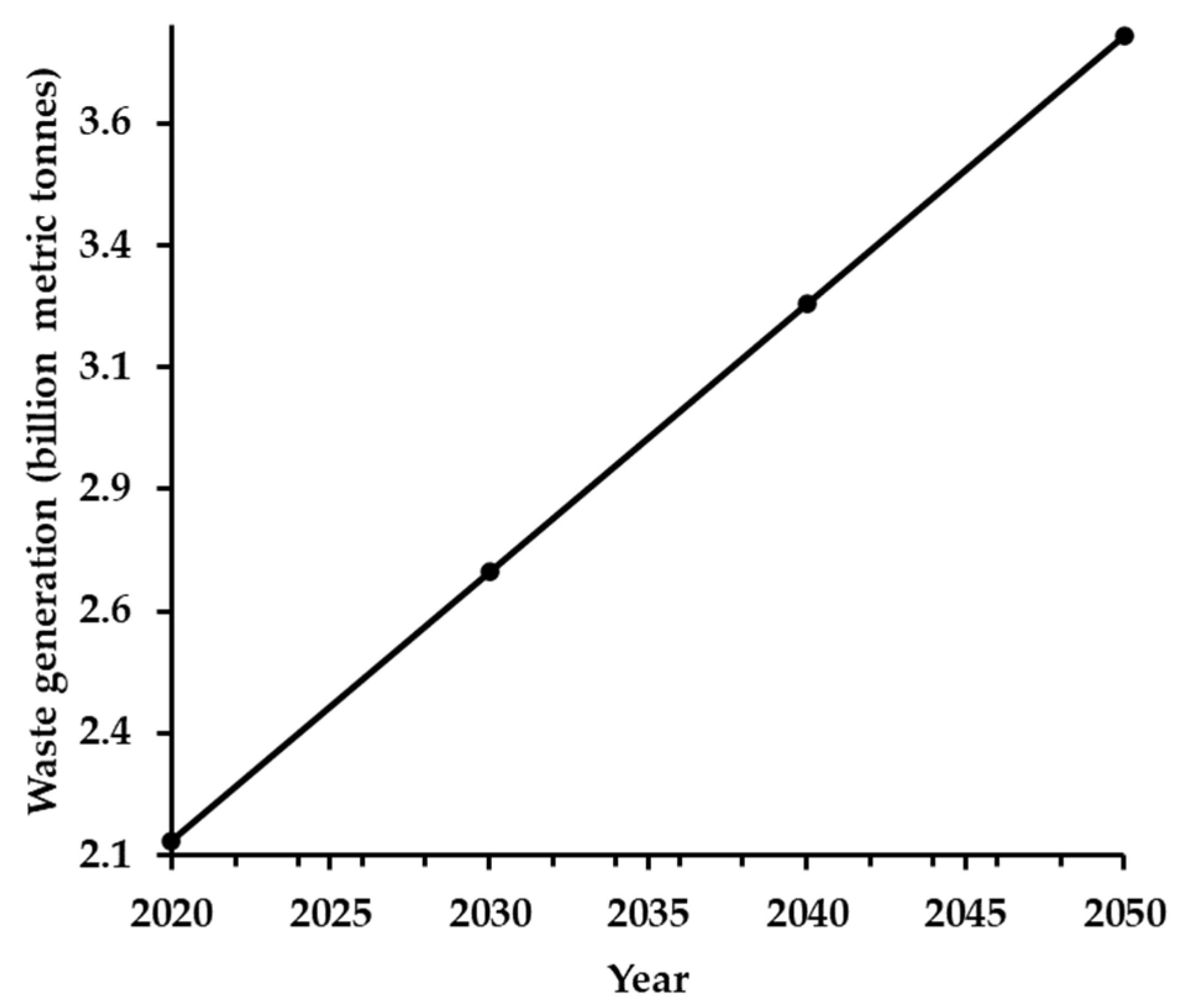

As shown in

Figure 1, global municipal solid waste generation is projected to rise sharply from 2.13 billion metric tonnes in 2020 to 3.78 billion metric tonnes by 2050 [

5]. This represents a nearly 78% increase over thirty years, showing greater pressure on the environment and more demand on waste management systems. Landfilling food waste causes it to decompose anaerobically, producing methane, a strong greenhouse gas that significantly contributes to climate change [

6]. This makes food waste landfills a major environmental concern. As the human population increases, the availability of free land for landfilling waste becomes increasingly limited. This shrinking space makes it essential to explore alternative methods for managing waste. Converting the maximum amount of waste into valuable materials, such as biomaterials, is essential for sustainable resource management.

Global greenhouse gas emissions reached a high of 53 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO

2e) in 2023, with coal combustion as a major contributor [

7]. Global CO

2 emissions from coal alone accounted for 15.4 GtCO

2 [

8]. Despite growing environmental concerns, many industries—including sponge iron, steelmaking, synthetic rutile production, and cement manufacturing—still heavily rely on coal. Bioresources have the potential to serve as renewable carbon feedstocks, offering a viable alternative to coal in these sectors. Currently, there is limited data on using bioresources to replace coal and reduce emissions. Therefore, the potential of bioresources to lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to coal is unclear and requires further study.

The world is increasingly seeking sustainable, greener, and cleaner materials, driving a growing demand for innovative biomaterials across various industries. For example, the construction sector is rapidly adopting biomaterials to reduce its carbon footprint and promote environmental sustainability [

9].

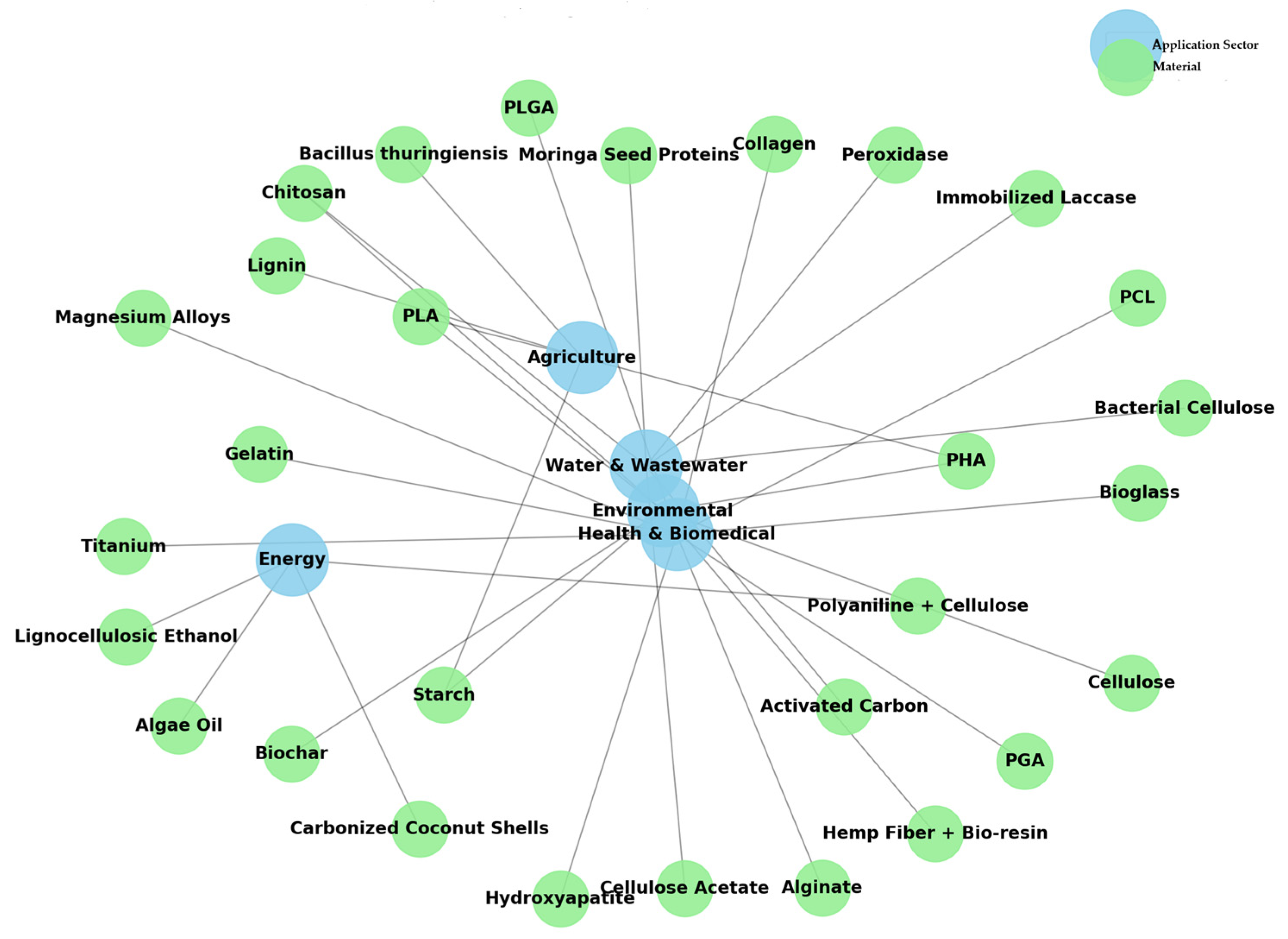

Figure 2 presents a network map showing the spatial arrangement of biomaterials and their associated application sectors. The key application sectors—agriculture, energy, environmental, health and biomedical, water, and wastewater—are denoted by blue nodes in the network map. In contrast, individual biomaterials, including chitosan, polylactic acid (PLA), collagen, and biochar, are represented by green nodes. This colour-coding facilitates clear differentiation between sectors and biomaterials within the visualisation. The use of specific biomaterials within designated sectors is depicted by connecting lines, facilitating the rapid identification of areas of intersection. For instance, chitosan is linked to the environmental, water, and wastewater sectors, whereas PLA is associated with the agriculture and environmental sectors.

The growing demand in the bioresources community for biomaterials production highlights the importance of understanding the properties of bioresources to produce biomaterials of high quality. Waste may represent a single source of bioresource or a combination of different types of bioresources. Understanding the type of waste and its key properties is essential for maximising the potential of waste-to-product conversion. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of bioresource properties and their impact on the quality and performance of biomaterials, as well as to explore recent advances in biomaterials production technologies.

2. Bioresources

2.1. Classification of bioresources

Bioresources are natural materials derived from biological origins and are primarily classified into plant-based, animal-based, microbial, marine, and algal resources. The diversity within these categories makes them valuable raw materials with numerous applications in agriculture, medicine, biotechnology, and industry. Additionally, these bioresources play a key role in supporting ecosystems, and their sustainable use is essential to maintain environmental balance and support various industries.

2.1.1. Plant-based

Plant-based bioresources originate from the ability of plants to harness sunlight through photosynthesis, converting carbon dioxide and water into energy-rich compounds that form vegetables, fruits, and biomass. These resources serve as the essential materials for countless organisms—humans, animals, and birds rely on them directly as food or indirectly through the food chain. Plants are valuable not only for their nutritional benefits but also for the important materials they supply for daily life. Wood from forestry becomes timber used in construction, furniture, and tools, while fibres such as cotton and jute are spun and woven into textiles.

Plant-based bioresources can be categorised into vegetables, fruits, crops (including cereals and legumes), forestry products, and industrial plants such as bamboo, hemp, and oilseed species. The life cycle of these biomaterials—from preparation and cultivation to production, processing, and end use—inevitably generates various forms of waste, including organic residues, by-products, and non-recyclable material. Understanding the types of waste associated with each category is essential for improving resource efficiency and promoting sustainable practices.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 outlines the main plant-based material categories alongside the corresponding waste types they produce.

2.1.2. Animal-based

Animal-based bioresource waste encompasses a wide variety of organic by-products generated from livestock, poultry, aquaculture, and related processing industries.

Table 6 shows wastes generated at various stages of production, including farming, slaughtering, processing, and product manufacturing. These wastes range from manure and poultry litter to fish waste, bones, feathers, and dairy by-products. If such waste is not managed properly, it can cause serious environmental and health risks, including contamination, unpleasant odours, and the spread of pathogens. However, when recovered sustainably, these materials can serve as valuable raw materials for bioproducts production. The potential uses and value of these wastes depend largely on the animal source, processing methods, and the nature of the end products.

Animal-based bioresource waste can be categorised into several groups based on its source and composition. Solid residues include materials such as manure, poultry litter, feathers, bones, hair, and wool, while processing by-products comprise gelatin and collagen waste, offal, tallow, and fat trimmings. Aquatic residues, including fish waste and crustacean shells, along with dairy and egg processing wastes such as whey, sludge, and eggshells, also form significant waste streams. Liquid wastes, such as manure slurry and slaughterhouse wastewater, contain high levels of organic matter and nutrients. Each type of waste has distinct physical and chemical properties, which affect its suitability for the extraction of valuable biomaterials.

2.1.3. Microbial

Microbial-based bioresources generate several types of solid waste during their processing and use.

Table 7 shows key waste categories include microbial biomass residues, which are leftover cell pellets such as yeast or bacterial biomass following fermentation or microbial growth. Another significant waste type is spent culture media, consisting of solid residues or dehydrated components remaining after microbial cultivation. These wastes arise from the core biological processes where microbes grow and metabolise nutrients, leaving behind residual biomass and depleted media.

Waste from microbial processes includes biological residues as well as contaminated lab and processing materials such as used petri dishes, disposable lab equipment, filter membranes, solid fermentation residues, and packaging waste. These wastes are produced at different stages, from cultivation through to processing and packaging. These wastes arise at various stages, from microbial cultivation to downstream processing and packaging. If not properly managed, this waste can pose environmental and health risks due to microbial contamination and plastic pollution. However, these wastes also present opportunities for bioproducts production, such as recovering valuable compounds or converting residues into useful materials.

2.1.4. Marine

Table 8 shows the types of waste generated from marine-based bioresources, which arise throughout the harvesting and processing of marine organisms. Marine bioresources are important to daily life as they supply food, medicines, and raw materials. In addition, they contribute significantly to the economy and environmental health while supporting communities. Wastes generated from marine-based bioresources include organic residues from fish and shellfish processing, microbial biomass from marine cultures. Packaging and plastic waste, such as containers, nets, and ropes, also contribute to the overall waste stream.

The generation of these wastes arises through various stages of marine resource harvesting and processing, posing environmental risks if not managed properly. Pollution from organic waste can lead to oxygen depletion in water, harming aquatic life, while plastic and chemical waste can cause physical damage, toxin accumulation, and disruption of habitats, all of which negatively impact marine ecosystems. However, when handled correctly, many of these waste materials have potential as raw materials for producing valuable bioproducts.

2.1.5. Algal

Algae play a vital role in maintaining ecological balance by producing oxygen through photosynthesis and serving as a primary food source in aquatic food webs. They also contribute to nutrient cycling and help purify water in both marine and freshwater environments. During the cultivation, harvesting, and processing of algal-based bioresources, various wastes are generated, as shown in

Table 9. These include leftover algal biomass after extracting bioactive compounds, oils, or pigments, broken or damaged fronds discarded during harvesting, concentrated sludge from dewatering, residual solids from spent growth media, and insoluble cell walls and debris remaining after processing.

Improper management of algal waste can lead to significant environmental problems, including nutrient pollution that may cause harmful algal blooms and oxygen depletion in aquatic systems. Additionally, solid wastes such as packaging contribute to physical pollution and disrupt natural habitats. On the other hand, if these wastes are properly utilised, they are suitable as valuable raw materials for producing bioproducts and other sustainable materials. Effective management of algal waste can thus help minimise environmental risks while promoting circular economy practices.

2.2. Physical properties

2.2.1. Plant-based

The physical characteristics of fruits—moisture content, bulk density, porosity, and texture—govern their degradation and potential as bioresources when discarded. For example, high-moisture, soft fruits (e.g., watermelon, strawberry) with moisture content of 89–93%, bulk density of 0.4–0.6 g/cm3, and porosity of 55–70% decompose rapidly due to their delicate structure. Firm-to-soft fruits (e.g., apple, mango, grape) with 80–87% moisture, bulk density of 0.5–0.7 g/cm3, and porosity of 40–50% degrade more slowly, retaining structural fibres and nutrients. Low-moisture, hard fruits (e.g., dried dates, tamarind, coconut) with 15–50% moisture, bulk density of 0.7–0.9 g/cm3, and porosity of 25–35% are more resistant to degradation, preserving concentrated nutrients over time. High-moisture, firm fruits (e.g., banana, pineapple) with 74–90% moisture, bulk density of 0.5–0.7 g/cm3, and porosity of 42–50% exhibit intermediate degradation rates, balancing water content and structural integrity. These properties collectively dictate the breakdown behaviour of fruit waste, shaping its potential as a bioresource.

2.2.2. Animal-based

Animal-based waste shows a wide range of physical properties depending on their source and processing. Manure from cattle, pigs, poultry, and sheep is typically moist and fibrous with a pasty texture due to high organic and water content, often ranging between 60–80% moisture, and a bulk density around 0.6–0.8 g/cm

3 [

10]. Liquid manure contains 85–95% water, making it pumpable, with suspended solids that impart a heterogeneous character. Poultry litter, a mixture of droppings, feathers, and bedding materials, is more heterogeneous, ranging from fine dusty particles to coarse fibrous bedding, with lower bulk density (~0.4–0.6 g/cm

3). In contrast, keratin-rich wastes such as feathers and hair are lightweight (0.02–0.1 g/cm

3), compressible, and hydrophobic [

11]. Bones are dense (1.7–2.0 g/cm

3), brittle solids with porous internal structures rich in calcium phosphate, while eggshells are similarly brittle, mineral-rich fragments (2.2–2.5 g/cm

3) with a porous microstructure [

12]. Gelatin and collagen residues, derived from bones, skins, and connective tissues, are soft, elastic, and water-absorptive when wet but become fibrous upon drying.

Soft tissues such as offal and fish processing residues possess high moisture content (70–80%), giving them a soft to rubbery texture, although fish bones and scales are harder and brittle [

13]. Crustacean shells, primarily chitin, are hard and brittle with densities of 1.2–1.4 g/cm

3, often forming sharp fragments. Wool waste is lightweight (0.03–0.05 g/cm

3), fibrous, and hydrophobic, yet internally absorbent. Dairy and slaughter by-products display distinct traits: whey is a low-viscosity liquid (~1.02 g/cm

3), sludge is semi-solid and creamy, while tallow and animal fat trimmings are greasy, semi-solid at room temperature (melting 35–45 °C) with a density near 0.9 g/cm

3, the latter being more heterogeneous due to connective tissue. Slaughterhouse wastewater is a cloudy, organic-rich effluent with a density close to water (1.0 g/cm

3) and elevated turbidity from suspended solids and fats [

14]. The physical characteristics and variations of animal-based wastes affect handling, processing, valorisation, and the rate and volume of waste generation.

2.2.3. Microbial

Laboratory and microbial solid wastes show diverse physical properties depending on their composition and usage. Leftover cell pellets from fermentation or microbial growth (e.g., yeast, bacteria) are semi-solid, moist, and heterogeneous with high water content (60–80%) and bulk densities of 0.5–0.8 g/cm

3 [

15]. Solid residues or dehydrated microbial media are typically dry, granular to powdery, friable, and low in moisture (<10%) with bulk densities around 0.4–0.6 g/cm

3 [

16]. Contaminated plastic or glass plates, pipette tips, swabs, inoculating loops, gloves, and masks are lightweight, polymer-based or rigid solids, flexible or brittle depending on material, and often retain microbial residues or moisture. Used filtration materials capturing microbial cells or spores are porous, fibrous, or membrane-based, compressible, and moderately loaded with moisture and biomass. Insoluble residues from solid-state fermentation are coarse, fibrous, and moderately moist (20–40%), while bags, containers, and wrappers of media and reagents are lightweight, flexible, and physically stable but potentially contaminated.

2.2.4. Marine

The physical characteristics of marine-based bioresource waste vary widely according to their source and method of processing. Fish processing wastes, such as skin, fins, offal, and carcasses, are typically moist, with water contents ranging from approximately 70–80% and exhibit soft to rubbery textures. In contrast, bones and scales are comparatively hard and brittle, with higher densities; for instance, fish scales have been reported to possess apparent densities around 0.49 g/cm

3, reflecting their rigidity and mineral content [

17]. Shellfish and crustacean wastes, such as shells and exoskeletons, are rigid, chitin-rich, brittle solids with densities of 1.2–1.4 g/cm

3 and often form sharp fragments [

18]. Fishmeal and fish oil residues are granular to coarse solids with moderate moisture content (10–20%) and bulk densities around 0.5–0.8 g/cm

3 [

19]

Marine microbial biomass residues are semi-solid to moist pastes, sticky and compressible, with heterogeneous particle sizes and high-water content. Marine sediment waste consists of fine, organic-rich particles and detritus, ranging from moist to semi-dry with variable bulk density and heterogeneous texture. Finally, packaging and plastic waste, such as containers, nets, and ropes, are lightweight, flexible or rigid polymer-based materials, low in bulk density (~0.3–0.9 g/cm3), physically stable, but often contaminated with residual moisture or organic matter. These physical properties are crucial for developing effective handling, processing, and valorisation strategies in marine industries.

2.2.5. Algal

Algal biomass shows considerable variation in physical properties depending on its type, moisture content, and processing stage. Fresh biomass and harvesting residues are typically soft, cohesive, and fibrous or gelatinous, with high moisture (75–90%), medium density (0.6–0.9 g/cm

3), and moderate porosity (20–35%). De-watered algal sludge is denser (0.9–1.1 g/cm

3) with lower porosity (10–25%) but remains moist and paste-like [

20,

21]. Partially dried cell walls and debris have moderate moisture (20–50%), medium density (0.4–0.7 g/cm

3), and higher porosity (35–55%), forming granular or fibrous particles, while settled biomass from spent growth media retains high moisture (70–85%) with medium–high density (0.8–1.05 g/cm

3) and fine, cohesive particles [

22].

These physical characteristics strongly affect waste handling and the suitability of algal biomass for bioprocessing. High-moisture, soft, and cohesive materials require dewatering or drying before conversion, whereas moderate-moisture, granular biomass is easier to transport, store, and feed into reactors. Dense, low-porosity residues are suitable for pelletising or producing structured biomaterials, while low-density, fibrous fractions can be used for composites, biofilms, or soil amendments, making the choice of processing route dependent on the specific physical properties of the biomass [

21,

22].

2.3. Chemical properties

2.3.1. Plant-based

Table 10 presents the ultimate analysis of various agricultural biomass residues. The data covers a wide range of residues, including cereal by-products (rice husk, corn stover, wheat straw), industrial residues (sugarcane bagasse, jute stick, rice bran wax), fruit and nut wastes (hazelnut, pinecone, okra, food waste), and woody biomass (sawdust, pine wood, alder wood, pine bark, wood kindling, gumtree sticks). Carbon content exhibits considerable variation, from approximately 35% in vegetable residues such as cucumber to over 76% in rice bran wax, reflecting differences in energy potential. Hydrogen content ranges between 4.7% and 15.1%, while nitrogen is generally low, except in protein-rich residues such as jute stick. Oxygen content shows an inverse relationship with carbon content, indicative of the relative lignocellulosic composition.

Table 11 shows the ultimate analysis of various fruit and palm biomass residues. The data include common fruit wastes such as orange peel, banana peel, apple pomace, olive mill solid waste, and grape pomace, as well as plum varieties (Bistrica, Cacanska lepotica, President, Stanley) and palm-derived residues including empty fruit bunch, palm kernel shell, and coconut shell. Carbon content ranges from around 40% in banana peel to over 55% in some plum varieties, reflecting differences in energy potential. Hydrogen content varies from 5.7% to 8.8%, while nitrogen is generally low, indicating limited protein content. Higher carbon content corresponds to lower oxygen, indicating differences in plant fibre and sugars.

2.3.2. Animal-based

Table 12 presents ultimate analysis of several animal-based bioresources. The differences in elemental content directly influence their calorific value, biodegradability, and suitability for processes such as anaerobic digestion, composting, or biochar production. For example, chicken feathers have a higher carbon and hydrogen content compared to manure, making them more energy-dense, whereas crustacean shells and pig manure have higher oxygen content, reflecting their more hydrated or mineral-rich composition.

2.3.3. Microbial

Microbial waste materials arise from laboratory and industrial processes and can be grouped into biomass-rich, cellulose-rich, and plastic-rich wastes.

Table 13 presents the estimated elemental composition (C, H, N, O, S) of various microbial waste materials, grouped by their chemical characteristics and material type. Elemental composition values are estimates based on commonly used materials and may vary in practice. Biomass-rich waste, such as microbial cell pellets, spent culture media, and solid fermentation residues, contain high levels of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen, making them suitable to produce bioproducts such as biofertilisers, biogas, enzymes, and single-cell proteins.

Cellulose-rich wastes, including cotton swabs and filter papers, are mainly polysaccharides with high carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen content; they are biodegradable and can serve as substrates for cellulose-based products such as bioethanol or organic acids. Plastic-rich waste, such as petri dishes, pipette tips, gloves, masks, synthetic membranes, and packaging, are composed of synthetic polymers with high carbon and hydrogen but negligible nitrogen and oxygen; they are largely non-biodegradable and are better suited for recycling or energy recovery.

2.3.4. Marine

Table 14 presents the elemental composition of selected marine waste materials on a dry basis. Values for fish tissue, fishmeal residues, and organic sediments are given as ranges, reflecting variability in species, processing, and mineral content; these are largely estimated from proximate analyses and literature data. More precise figures are available for fish scales and chitin, derived from direct elemental analyses or empirical formulae. Microbial biomass composition is calculated from accepted empirical biomass models used in stoichiometric studies, while polymer fractions (PE, PP, PET, nylon-6) are expressed as theoretical repeat-unit compositions based on molecular structure.

2.3.5. Algal

Table 15 shows the ultimate analysis of various algal-based waste materials, detailing their elemental composition and potential uses. Microalgae, such as Chlorella and Spirulina, have high carbon content (49–52%) and nitrogen (10–11%), moderate hydrogen (6–7%) and low sulfur (0.55–0.60%), indicating significant protein and carbohydrate content suitable for bioenergy and biochemical applications [

51].

By contrast, algal waste residues contain lower carbon (35.3%) and nitrogen (4.44%) but higher oxygen (54.85%), reflecting the remaining structural polysaccharides after extraction [

52]. Macroalgae, including Ulva sp., Green algae, Blue-green algae, and Undaria pinnatifida, show a wide range of carbon (5.8–44.9%) and nitrogen (0.68–7.4%) levels, due to differences in species, cell wall composition, and processing methods [

53]. This variation highlights the need for species- and process-specific analysis when utilising algal waste materials.

3. Biomaterials

3.1. Biocarbon

3.1.1. Biochar

Biochar is a solid carbon-rich material produced from a wide range of bioorganic feedstocks, including waste materials derived from plant-based, animal-based, microbial, marine, and algal resources (as outlined in

Table 1–5). Biochar is produced from any bioresource through carbonisation or pyrolysis. During this process, thermal decomposition occurs, and volatile compounds are released, resulting in the formation of solid carbon, known as biochar, which retains a partially porous structure. Concurrently, gasification reactions transform some of the biomass and volatiles into syngas components such as carbon monoxide, hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide.

Table 16 shows the main chemical transformations in gasification, including pyrolysis, oxidation, reduction, and tar reforming.

Biochar can be produced using several methods, each differing in temperature, residence time, and product characteristics, as shown in

Table 17. Slow pyrolysis produces a high yield of biochar, making it suitable for soil improvement, but it requires long processing times and moderate heat. In contrast, fast pyrolysis generates bio-oil quickly, although the biochar yield is lower. Gasification produces energy-rich syngas and a moderate amount of char; however, it operates at very high temperatures, which makes the process energy-intensive. Hydrothermal carbonisation efficiently converts wet biomass into hydrochar without the need for drying, though it requires pressurised reactors. Torrefaction increases the energy density and improves the handling of biomass, but results in lower biochar yields. Microwave pyrolysis offers fast, uniform, and energy-efficient heating, although scaling up the process can be challenging. Finally, flash carbonisation produces highly porous char suitable for industrial applications, but its extreme temperatures and very short residence times limit practicality for large-scale operations.

3.1.2. Bioactivated carbon

Bioactivated carbon produced from biochar is a highly versatile material characterized by its well-developed internal porosity, abundant functional structures, and exceptionally high internal surface area, typically ranging from 30 to 3000 m

2/g [

60]. These properties make it highly effective for applications such as adsorption, catalysis, and environmental remediation. The performance of bioactivated carbon is largely determined by the activation process, which enhances pore structure, surface chemistry, and overall adsorption capacity.

There are three primary production methods for bioactivated carbon: thermal, chemical, and thermochemical activation [

61]. Thermal activation involves heating biochar to temperatures between 800 °C and 1100 °C in the presence of activating agents such as air, CO

2, or H

2O, promoting the development of a highly porous structure. Chemical activation occurs at lower temperatures, typically between 500 °C and 1000 °C, using chemical agents like H

3PO

4, KOH, K

2CO

3, NaOH, or ZnCl

2 to introduce additional functional groups and enhance surface area [

62]. Thermochemical activation combines thermal and chemical methods, leveraging the advantages of both to produce bioactivated carbon with superior porosity, functional structures, and adsorption performance. The key chemical reactions that occur during biomass carbonization and the production of activated carbon are summarised in

Table 18.

Table 19 presents the diverse applications of activated carbon across industries, highlighting its critical role in purification, pollutant removal, and resource recovery. Activated carbon and biochar are valued for their high surface area and strong adsorption properties, enabling their use in air and water treatment, heavy metal removal, and industrial effluent management. They are also applied in pharmaceuticals, food processing, energy storage, and environmental remediation, making them essential materials for both sustainability and health-related applications.

3.2. Biomaterials

3.2.1. Catalytic biomaterials

Catalytic biomaterials are synthesised from diverse classes of raw materials, including metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles, carbon-based matrices such as graphene and biochar, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), transition metal systems, natural biomolecules, and biocompatible polymeric or hydrogel platforms. Recently, biowaste has emerged as a sustainable feedstock for developing low-cost catalytic materials.

Table 20 lists catalytic materials prepared from different biowaste sources and their typical applications. Eggshells, predominantly composed of calcium carbonate, can be calcined to produce calcium oxide (CaO), which serves as an efficient heterogeneous base catalyst. Such materials have been applied extensively in biodiesel production, achieving high fatty acid methyl ester yields with minimal catalyst loadings [

63]. Modification of eggshell-derived CaO, such as doping with alkali compounds, further enhances catalytic performance and stability. These results underscore the potential of biogenic CaO as a viable alternative to conventional catalysts in base-catalysed transformations.

Lignocellulosic residues such as coconut shells and husks have been widely explored for biochar and activated carbon production [

64]. These carbonaceous materials, often modified through doping or metal impregnation, are used as catalyst supports and exhibit activity in applications such as biodiesel synthesis, adsorption, and electrocatalysis [

65]. Nitrogen-doped carbons derived from coconut biomass have demonstrated strong performance in oxygen reduction reactions (ORR), highlighting their relevance for renewable energy applications. Simultaneously, calcium-based catalysts from shells and carbon-based catalysts from plant residues represent two of the most established pathways for valorising biowaste into catalytic materials.

3.2.2. Dental biomaterials

Dental biomaterials made from biowaste are becoming increasingly important because they are sustainable, biocompatible, and useful in regenerative dentistry. One of the most extensively studied materials is eggshell-derived hydroxyapatite (E-HAp), obtained from chicken eggshells [

73]. E-HAp is rich in calcium and exhibits excellent bioactivity, making it suitable for bone grafts, implant coatings, and remineralization agents. A recent study found that E-HAp can enhance osteoconductivity and promote tissue regeneration, providing a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic hydroxyapatite [

73]. Other biowaste-derived materials are also proving useful in dental and bone tissue engineering. Starch-based nanocomposites made from agricultural waste, such as corn, can be used to produce biodegradable scaffolds with controlled porosity for bone regeneration [

74]. Similarly, cerium-containing mesoporous bioactive glasses, derived from cerium oxide waste, offer antioxidant properties that support bone regeneration while reducing oxidative stress in surrounding tissues [

75].

Collagen-rich biowaste, such as animal tendons, has been used to make atelocollagen-based hydrogels for guided bone regeneration. These hydrogels offer structural support and resist breakdown, aiding tissue healing and integration [

76]. Additionally, dental-derived stem cells obtained from human dental pulp are being explored for regenerative therapies in bone and dental tissue repair, demonstrating the potential of biowaste not only as a material resource but also as a source of regenerative cells [

77]. Overall, these developments demonstrate how biowaste can be repurposed to produce effective, sustainable dental biomaterials.

3.2.3. Electroactive biomaterials

Biowaste-derived electroactive biomaterials provide sustainable and functional alternatives for energy, biomedical, and electronic applications. For example, fish scales containing collagen and hydroxyapatite have been engineered into bio-piezoelectric nanogenerators capable of harvesting ambient mechanical energy such as vibration and touch [

78]. Similarly, crab shell powder combined with PVDF (Polyvinylidene fluoride) nanofibers has been developed into composite piezoelectric devices for wearable sensors and power harvesting [

79]. Agro-industrial waste is another abundant feedstock, often processed into activated carbon electrodes with high surface area and tunable porosity, making them suitable for supercapacitors, flexible energy storage, and sensing applications [

80].

Other waste streams also yield electroactive materials with diverse functionalities. Cow dung can be converted into conductive carbon black pigments for paints, coatings, and energy storage applications, demonstrating high capacitance and low sheet resistance [

81]. Eggshells, mainly composed of calcium carbonate and hydroxyapatite, serve as bioceramic fillers in bone scaffolds and implants, and when modified with conductive additives, they exhibit electroactive behavior [

82]. In addition, biowaste-derived nanomaterials such as carbon dots, graphene, and carbon nanotubes enable broad applications in biosensing, imaging, optoelectronics, tissue engineering, and drug delivery [

83]. These examples highlight how biowaste valorization into electroactive biomaterials can support both circular bioeconomy principles and next-generation technological innovation.

3.2.4. Extracellular matrix biomaterials

Extracellular matrix (ECM) biomaterials derived from biowaste represent sustainable and functional alternatives to conventional scaffolds for tissue engineering and wound repair. Fish skin, when decellularized, retains collagen and ECM proteins that accelerate wound closure in burns and diabetic ulcers while reducing pain and treatment costs [

84]. Fish scales, rich in collagen and hydroxyapatite, provide osteoconductive scaffolds for bone grafting and guided bone regeneration [

85]. Eggshell membrane (ESM), a collagenous fibrous structure from poultry waste, has demonstrated biocompatibility and osteogenic potential, supporting mineralization, cell proliferation, and tissue repair [

86]. In parallel, crustacean shell waste provides chitin and its derivative chitosan, which can be fabricated into hydrogels, porous scaffolds, and dressings with antimicrobial, hemostatic, and tissue-regenerative properties [

87].

Other ECM-like scaffolds include human amniotic membrane (hAM), derived from obstetric by-products, which promotes re-epithelialization via modulation of TGF-β and EGF pathways, enabling chronic wound healing and reducing pathological inflammation [

88]. Decellularized porcine and bovine dermis from abattoirs are also widely used as acellular dermal matrices in soft tissue repair and skin substitutes [

89]. More recently, decellularized plant tissues such as spinach leaves have emerged as low-cost, cellulose-based scaffolds with perfusable vasculature, providing unique platforms for vascularized tissue engineering [

90]. Overall, these ECM biomaterials demonstrate the effective conversion of biological waste into biocompatible and functional scaffolds suitable for regenerative medicine and advanced biomaterial applications.

3.2.5. Injectable biomaterials

Injectable biomaterials derived from renewable bioresources are increasingly employed for tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and drug delivery applications due to their biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and ease of administration. Chitosan-based hydrogels, obtained from crustacean shells, are widely studied for wound healing, controlled drug release, and scaffold fabrication, offering antimicrobial properties and biodegradability [

91]. Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), synthesized from animal skin collagen, has been applied in 3D bioprinting and bone tissue engineering, providing cell-adhesive motifs and photo-crosslinkable properties that allow precise shape formation and mechanical tuning [

92]. Similarly, eggshell-derived hydroxyapatite serves as an injectable bone cement and scaffold filler, providing osteoconductivity and supporting bone regeneration [

93]. Nanocellulose-based hydrogels and starch-derived composites, sourced from agricultural biowaste, have shown potential as 3D scaffolds for tissue culture and bone regeneration due to their high surface area, tunable porosity, and mechanical stability [

87].

3.2.6. Nanocomposite biomaterials

Biowaste has become a valuable raw material for producing nanomaterials that can be incorporated into biomaterial composites. For example, eggshell waste is a rich source of calcium carbonate, which can be thermally or chemically converted into hydroxyapatite (HAp) nanoparticles. Studies have shown that eggshell-derived HAp blended with biodegradable polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL) or polylactic acid (PLA) enhances scaffold bioactivity and mechanical strength, making them suitable for bone tissue engineering [

94]. Similarly, fish scales, another calcium-rich waste stream from the fishing industry, can also be processed into HAp. These fish-scale-derived particles have been successfully used in bioceramic and polymer scaffolds for load-bearing implants, showing comparable performance to commercial HAp [

95].

Another major biowaste source is shrimp and crab shells, which contain chitin that can be deacetylated to produce chitosan. Chitosan is widely studied for its antimicrobial activity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. For instance, shrimp-shell-derived chitosan nanoparticles incorporated into polymeric scaffolds or blended with magnesium oxide have been shown to improve mechanical stability and antimicrobial function in wound dressings and drug delivery systems [

96]. Beyond animal waste, agricultural residues such as rice husks, sugarcane bagasse, coconut husks, and banana peels are also being transformed into nanosilica or nanocellulose. Rice husk-derived nanosilica, for example, has been applied as a reinforcing phase in biopolymers and coatings, while nanocellulose from sugarcane bagasse or banana peels has been incorporated into hydrogels and films to improve tensile strength and biodegradability [

97,

98,

99,

100].

3.2.7. Piezoelectric biomaterials

Piezoelectric materials convert mechanical stress into electrical signals, enabling their use in sensors, actuators, and energy harvesters. Traditional ceramic-based piezoelectrics offer high efficiency but are limited by toxicity, brittleness, and poor biocompatibility. To overcome these drawbacks, biowaste-derived proteins and polysaccharides such as collagen, chitin, silk fibroin, keratin, and alginates are being developed into piezoelectric films, fibres, and hydrogels. These materials are renewable, biodegradable, and inherently biocompatible, making them particularly attractive for biomedical and wearable technologies [

101,

102,

103].

Table 21 presents biowaste sources, their processing methods, and corresponding applications in piezoelectric materials.

Different biowaste sources yield distinct piezoelectric platforms: fish scales provide collagen-based scaffolds for tissue engineering and energy harvesting [

104]; crustacean shells produce chitosan nanofibers for wound dressings and flexible sensors [

101]; silk fibroin from cocoons forms electrospun fibres for neural scaffolds and biosensors [

105]; and keratin from feathers or wool enables flexible piezoelectric films for sensing and regenerative medicine [

106]. Additional sources include eggshell membranes, which serve as collagen-rich piezoelectric membranes for bone scaffolds and wearable sensors [

107], and algae biomass, which can be processed into alginate or carrageenan hydrogels for soft, biocompatible piezoelectric platforms and drug delivery [

108]. Performance improvements are often achieved through fibre alignment (e.g., electrospinning) or by forming composites with synthetic polymers such as PVDF. These strategies highlight the potential of biowaste valorisation to create sustainable, high-performance piezoelectric materials for next-generation biomedical and wearable applications.

Table 21.

Biowaste sources, processing, and applications of piezoelectric materials.

Table 21.

Biowaste sources, processing, and applications of piezoelectric materials.

| Biowaste source |

Processing |

Piezoelectric material |

Potential applications |

References |

| Fish scales |

Collagen extraction (acid/enzymatic) |

Collagen-based films/scaffolds |

Tissue engineering, wearable sensors |

[109,110] |

| Crustacean shells (shrimp/crab) |

Chitin extraction → deacetylation → chitosan |

Chitosan films/nanofibers |

Wound dressings, flexible piezoelectric sensors |

[111] |

| Silk cocoons (sericulture waste) |

Degumming → fibroin isolation → electrospinning |

Silk fibroin nanofibers/films |

Neural scaffolds, biosensors |

[103] |

| Keratin from feathers/wool |

Reduction/hydrolysis → film casting or electrospinning |

Keratin-based piezoelectric films |

Flexible sensors, tissue engineering |

[102] |

| Eggshell membranes |

Demineralization → membrane isolation |

Collagen-rich membrane |

Bone tissue scaffolds, biosensors |

[112] |

| Algae biomass |

Polysaccharide extraction → hydrogel formation |

Alginate/carrageenan composites |

Soft piezoelectric hydrogels for drug delivery |

[108] |

3.2.8. Smart biomaterials

The conversion of biowaste into smart biomaterials integrates circular economy principles with the design of advanced functional materials. Crustacean shells, which are abundant in chitin, illustrate this approach well. Through deproteinisation and deacetylation, chitosan is produced and further processed into pH- and temperature-responsive hydrogels as well as antibacterial films. Such materials are highly relevant in biomedical fields, including wound dressings, drug delivery systems, and smart coatings, where their responsiveness to physiological conditions allows controlled therapeutic function [

113,

114,

115]. Similarly, fruit peels provide a renewable source of anthocyanins, pectin, and cellulose. Extracted using solvent-based or ultrasound-assisted techniques, these compounds can be incorporated into pH-sensitive films that alter colour with environmental changes, supporting applications in spoilage detection and intelligent food packaging [

113].

Biowaste materials such as rice husks and sugarcane bagasse represent scalable feedstocks for the development of smart biomaterials. Rice husks can be processed to obtain nanocellulose and silica, which, when combined, form composites with improved mechanical strength and bioactivity. These composites are well-suited for applications in bone scaffolds, biosensors, and advanced structural materials [

116]. Nanocellulose derived from sugarcane bagasse can also be functionalised to produce thermo- and pH-responsive hydrogels, enabling use in drug delivery systems and absorbent materials [

113]. Furthermore, coffee grounds provide a source of polyphenols and carbon dots through solvent extraction and pyrolysis, yielding conductive or fluorescent coatings that show potential in biosensors, flexible electronics, and bioimaging [

113].

Other bioresources, including fish scales, algal biomass, and brewery spent grains, further expand the potential for functional biomaterial development. Fish scales are a source of collagen and hydroxyapatite, which can be processed into hydrogels and bio-inks for applications in tissue engineering and bioelectronics [

117]. Algal polysaccharides such as alginate and carrageenan can be crosslinked with calcium ions to form ion-responsive hydrogels, supporting controlled drug delivery and smart wound dressing systems [

113]. Brewery spent grains, rich in proteins, fibres, and phenolic compounds, can be enzymatically hydrolysed to produce antioxidant and stimuli-responsive films suitable for active food packaging and nutraceutical coatings [

116]. Collectively, these cases demonstrate how industrial and agricultural residues can be transformed into high-value, stimuli-responsive biomaterials, linking sustainability with innovation across biomedical, packaging, and electronic applications.

3.3. Biometals

3.3.1. Bioiron

Biowaste, particularly lignocellulosic wood waste including off-cuts, sawdust, residues from construction and demolition, and discarded wood products, is of biological origin and thus recognised as a biomaterial as well as a renewable resource. Such materials are of significant value as they provide sustainable alternatives to fossil-based materials like coal, reducing reliance on non-renewable resources. Notably, waste wood shows considerable potential in metallurgical applications [

118], where carbon-rich fractions of these biomaterials can be utilised in the reduction of iron ore to produce bioiron, contributing to more sustainable and low-carbon steelmaking pathways [

119,

120].

Ongoing research is focused on bioiron production, although no technology has yet progressed beyond laboratory-scale testing, where results have been promising. One approach under development is Rio Tinto’s bioiron process, which uses Pilbara iron ores together with raw biomass from agricultural by-products such as sugarcane bagasse, canola straw, barley straw, rice stalks, and wheat straw [

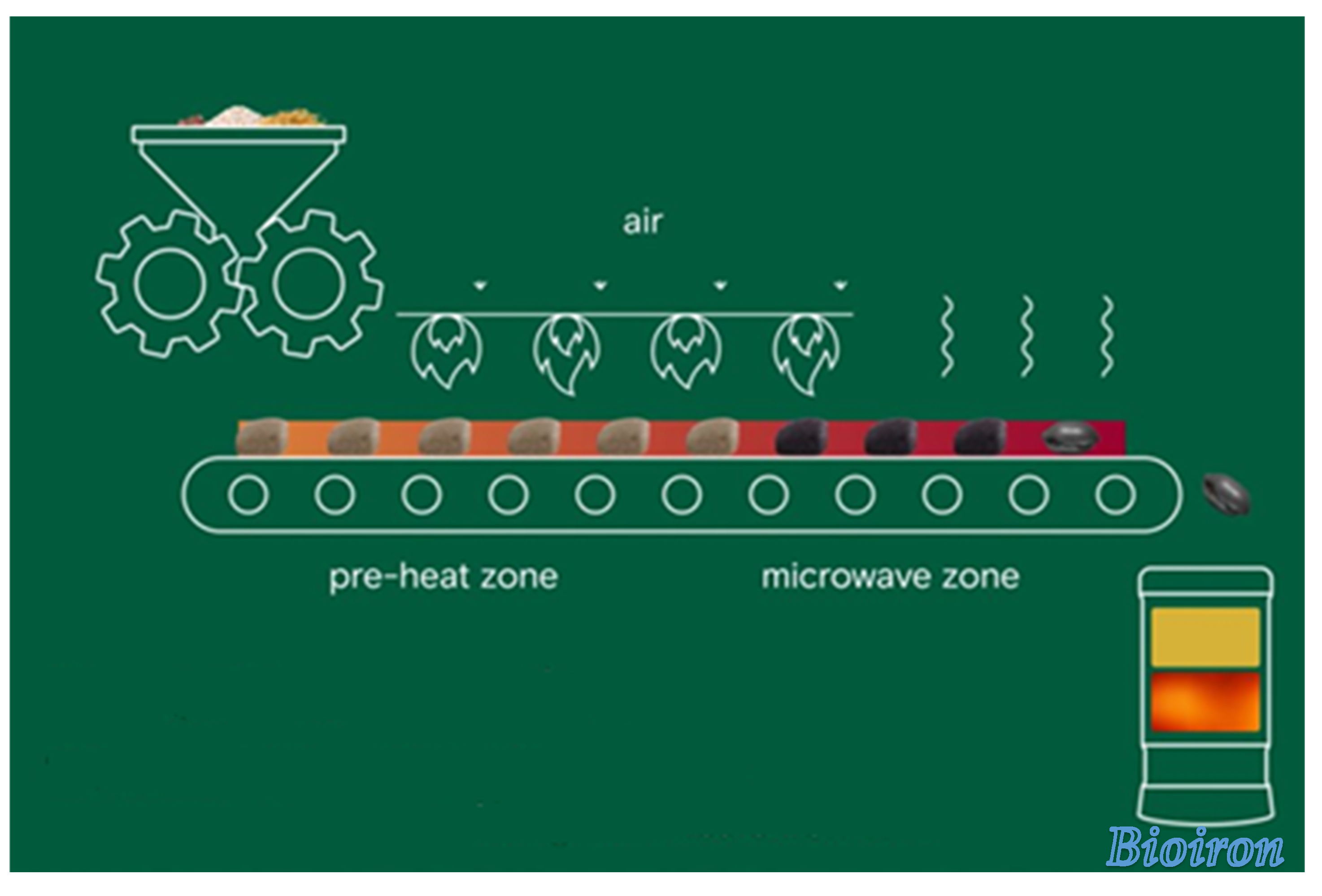

119]. In this process, microwave energy is applied to reduce the iron ore to metallic iron. As shown in

Figure 3, the proposed bioiron pilot plant in Australia involves an initial pre-heating stage with air, followed by a microwave zone where the reduction of iron ore occurs. This method highlights the potential of combining renewable biomass with microwave heating to provide a more sustainable pathway for iron production.

Another method for bioiron production involves using low-grade iron ore, such as goethite, mixed with waste wood in a rotating kiln furnace operated at around 1100 °C with a holding time of two hours [

120]. Under these conditions, the iron oxide (Fe

2O

3) is effectively reduced to metallic iron, with reported reduction levels exceeding 92%. A further advantage of this process is the generation of valuable by-products, including biochar and bioactivated carbon. The biochar produced has a surface area of approximately 684 m

2/g, while the activated carbon achieves around 770 m

2/g, indicating high reactivity and potential for wider applications [

120]. This approach demonstrates the potential for producing metallic iron alongside sustainable carbon-rich materials, offering a multiproduct, low-emission pathway for ironmaking.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the bioiron process [

121].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the bioiron process [

121].

3.3.2. Bio-based green steel

Steelmaking is one of the most carbon-intensive industries, with current processes heavily dependent on coal both as a fuel and as a reducing agent to extract iron from its ores. This reliance contributes around 2.8 gigatonnes of CO

2 emissions each year—nearly 8% of global emissions—making steel production a major focus for decarbonization efforts [

122]. Research is underway to replace coal with hydrogen as a reducing agent, powered by renewable energy, to convert iron ore (Fe

2O

3) into metallic iron [

123]. This route significantly reduces emissions since hydrogen reduction produces water vapor instead of carbon dioxide.

However, steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, meaning that some carbon remains essential in the process. Direct reduction of iron using hydrogen can yield pure iron, which can then be combined with sustainable carbon sources such as biochar to produce steel. By substituting fossil coal with hydrogen and biochar, the industry can maintain the critical properties of steel while substantially lowering its carbon footprint. This hybrid pathway offers a promising route toward sustainable steelmaking without compromising material quality.

Not all biochar types are suitable for steelmaking — the best candidates are those with high fixed carbon, low ash, and minimal sulfur and phosphorus, since impurities can affect steel quality. Woody biomass biochar is considered the most suitable, as it closely resembles traditional charcoal used in early ironmaking. Agricultural residues and energy crop biochar can also be used if processed properly, but they often need stricter control of ash composition.

3.3.3. Biotitanium

Titanium (Ti) is a critical element primarily extracted from titanium ores such as rutile, leucoxene, ilmenite, and other titanium-rich minerals. Its unique properties, including high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility, make it highly valuable across a wide range of everyday and industrial applications. Titanium dioxide is widely used in paints, plastics, paper, welding rods, and fibreglass due to its brightness and durability [

124]. Also, titanium metal plays a crucial role in advanced industries, particularly in the production of aircraft, spacecraft, and space exploration equipment, where strength and lightness are essential. In the medical field, titanium is used in surgical implants because it is safe and compatible with the human body. More recently, consumer electronics such as premium smartphones, including Apple’s iPhone, have adopted titanium for its durability, sleek finish, and lightweight strength [

25].

Producing titanium metals for biomedical applications requires raw materials with high TiO

2 content, such as rutile or synthetic rutile. High-grade titanium minerals such as rutile, which contain more than 92% TiO

2, are scarce in nature, making alternative sources important for titanium production. Ilmenite, with a TiO

2 content of over 50%, is the main feedstock for producing synthetic rutile, which is typically upgraded to contain more than 92% TiO

2. The conventional route for synthetic rutile involves the reduction of ilmenite with carbon, followed by leaching to remove impurities [

118]. While coal has traditionally been used as the reducing agent, growing interest in sustainable processing has turned attention towards renewable bioresources such as waste wood and agricultural residues. Recent research has shown that biochar derived from waste wood and gumtree sticks can successfully reduce ilmenite, making them suitable for “biorutile” production. This approach cuts reliance on fossil carbon and uses biomass waste, making titanium mineral processing more sustainable.

3.4. Bioplastics

In 2024, global plastic production was approximately 413.8 million tonnes, distributed regionally as follows: China 33.3%, Asia (excluding China and Japan) 19.7%, North America 17.1%, Europe 12.3%, Middle East and Africa 8.5%, Central and South America 3.8%, and Japan 2.8% [

125]. Within this total, mechanically recycled post-consumer plastics represented 8.7%, while chemical recycling contributed only 0.1%. Additionally, bio-based and bio-derived plastics made up just 0.7%, or around 3 million tonnes. In 2023, Asia led global bioplastics production with 51% of capacity, followed by Europe at 27%, North America at 14%, and South America at 8% [

126]. Despite rising global concern over plastic pollution, sustainable alternatives continue to make up only a tiny fraction of total global plastic production.

The data in

Table 22 highlight the diversity of global bioplastic producers in terms of both feedstocks and conversion technologies. The most common raw materials are sugarcane and corn, widely used because of their high carbohydrate content and established processing routes. Sugarcane ethanol serves as a key feedstock for bio-based polyethylene (bio-PE) in companies such as Braskem and Mitsubishi Chemical, while corn starch and its derivative glucose are central to polylactic acid (PLA) production by NatureWorks LLC and Toray Industries. Less common feedstocks include potato starch, cellulose, and vegetable oils, which are utilized by companies like Biome Bioplastics, Novamont, and Danimer Scientific. These materials are often employed through microbial fermentation or blending to yield biodegradable products such as Mater-Bi

® or polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). This distinction shows that while sugarcane and corn dominate as mainstream bioplastic feedstocks, alternative raw materials play a niche but growing role in diversifying product functionality and biodegradability.

The analysis shows that the choice of conversion pathway is closely linked to the intended product function and market strategy. Drop-in bioplastics, such as Braskem’s bio-PE, adopt conventional petrochemical routes (ethanol → ethylene → polymerization) because they allow direct substitution of fossil-based plastics without requiring changes in existing processing infrastructure or applications. In contrast, producers targeting biodegradable alternatives, such as PLA, PHA, and Mater-Bi®, select more complex fermentation and polymerization routes. These methods, while less streamlined, enable the creation of polymers with novel functional properties, including biodegradability and compostability, which address growing sustainability demands. Thus, the preference for drop-in pathways is driven by compatibility with established markets, whereas the adoption of fermentation-based routes reflects the need to meet environmental performance criteria and specialized applications.

3.4. Building biomaterials

Bricks are fundamental to construction due to their strength, durability, and versatility; however, the environmental impact of conventional brick production has driven the development of bio-bricks, an innovative and sustainable building material designed to mitigate CO2 emissions and promote greener construction practices. They are produced by combining cement with organic additives, such as lignin extracted from coffee husks, bovine excreta, and other biowaste materials including rice husks, straw, sawdust, and sugarcane bagasse, resulting in a biodegradable, low-impact alternative to conventional bricks.

In a recent study [

137], the lignin was sieved through mesh number 200 to achieve uniform particle size, and the mixture was carefully optimised to balance structural integrity with sustainability. Elemental analysis of the optimised bio-brick revealed a complementary composition that supports both structural performance and sustainability. Cement, rich in calcium and silicon, provides the primary binding matrix, contributing to the brick’s compressive strength and rigidity. Lignin, containing elevated levels of potassium and copper, acts as a natural reinforcement, improving mechanical resilience and enhancing durability through its fibrous, polymeric structure. Bovine excreta, dominated by carbon and oxygen, serves as an organic filler that reduces density, promotes biodegradability, and supports a closed-loop lifecycle. The minor contributions from other elements further stabilise the matrix and may enhance thermal and chemical properties, making this composition particularly suitable for environmentally friendly, low-load-bearing construction.

3.5. eTextiles

Bio-based e-textiles are increasingly recognised as sustainable alternatives to conventional electronic textiles, integrating renewable and biodegradable materials into functional fabrics. Materials such as cellulose-based fibres from wood or agricultural waste, lyocell (Tencel), bacterial cellulose, and abacá offer versatile platforms for conductive textiles, sensors, and wearable medical devices. Engineered biopolymers such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and synthetic spider silk provide mechanically robust, eco-friendly substrates suitable for high-performance wearable electronics. Furthermore, composites incorporating graphene or silver nanoparticles enhance electrical conductivity while maintaining biodegradability, facilitating the development of environmentally responsible wearable systems [

138,

139].

Fungal mycelium and bacterial cellulose are highly promising materials for flexible, lightweight, and biodegradable sensor substrates. Mycelium can serve as a leather-like material or structural support, while bacterial cellulose offers excellent mechanical strength and readily accommodates conductive coatings [

140,

141]. Together, these bio-derived materials support the development of wearable devices for health monitoring, fitness tracking, and interactive textiles, all while substantially reducing the environmental impact compared with synthetic fibres. By combining renewable resources, microbial polymers, and advanced nanocomposites, it is possible to create next-generation smart textiles that are both high-performing and sustainable [

138,

139].

4. Effect of bioresources properties on biomaterials development and applications

4.1. Effect of plant-based

Plant-based bioresources offer versatile feedstocks for biomaterials due to their intrinsic physical properties. Moisture content, bulk density, porosity, and texture govern degradation rates, handling, and processing behaviour. High-moisture, soft fruits such as watermelon and strawberry (89–93% moisture, 0.4–0.6 g/cm

3, 55–70% porosity) degrade rapidly, making them suitable for nutrient-rich biopolymers or biochar, but limiting storage [

Table 1 and

Table 2]. Firmer fruits, including apple, mango, and grape (80–87% moisture, 0.5–0.7 g/cm

3, 40–50% porosity), retain structural fibres, enabling use in composite materials and fibrous reinforcements [

Table 1 and

Table 2]. Low-moisture, hard fruits like dried dates, tamarind, and coconut (15–50% moisture, 0.7–0.9 g/cm

3, 25–35% porosity) resist degradation, providing long-term stability for high-density biocomposites or activated carbon [

Table 1 and

Table 2].

Chemical composition further defines suitability for specific applications. Carbon content varies widely among plant residues—from 35.7% in cucumber to over 76.8% in rice bran wax—affecting energy potential and the development of carbon-based materials such as biofuels, bioplastics, and piezoelectric composites [

Table 10]. Hydrogen (4.7–15.1%) and nitrogen, generally low except in protein-rich residues such as jute stick, influence reactivity and crosslinking potential, relevant for polymeric and structural materials [

Table 10]. Oxygen content inversely correlates with carbon, reflecting lignocellulosic composition and affecting thermal and mechanical stability, which determines performance in high-strength or high-temperature bioproducts.

Fruit and palm residues display similar variability in composition, with carbon ranging from ~40% in banana peel to over 55% in certain plum varieties, and low nitrogen content [

Table 11]. High-carbon, low-oxygen residues are particularly suited to biochar, energy storage materials, and conductive composites, whereas high-moisture or high-porosity residues are ideal for biodegradable films, hydrogels, and aerogels [

Table 10 and

Table 11]. Careful selection of plant residues based on their physical and chemical properties allows optimisation of biomaterial performance while maximising resource efficiency and sustainability.

4.2. Effect of animal-based

Animal-based bioresources generate diverse wastes from livestock, poultry, aquaculture, and processing industries, including manure, feathers, bones, offal, and dairy by-products [

Table 6]. Their physical properties—moisture content, bulk density, texture, and structural composition—determine handling, processing, and suitability for bioproducts. High-moisture, fibrous residues such as manure and slurry (60–95% moisture, 0.4–0.8 g/cm

3) are ideal for composting, anaerobic digestion, or fertiliser production, while keratin-rich wastes like feathers and hair (0.02–0.1 g/cm

3) can be used for bioplastics, composites, or nitrogen-rich additives. Dense, brittle materials such as bones and eggshells (1.7–2.5 g/cm

3) provide mineral-rich feedstocks for hydroxyapatite, bioceramics, or adsorbents, whereas gelatin and collagen residues are elastic and water-absorptive, suitable for films, hydrogels, and scaffolds. Soft tissues, offal, fish residues, and crustacean shells further expand application potential, supporting bio-lubricants, chitin extraction, and nutrient recovery.

Chemical composition strongly influences functionality and energy potential. Carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur, and oxygen contents vary widely among residues [

Table 12], determining suitability for biofuels, biopolymers, and biochar. Chicken feathers, with high carbon and hydrogen, are energy-dense and suited to bio-composites, while crustacean shells and pig manure, richer in oxygen and minerals, are ideal for chitin, fertilisers, and mineral-based biomaterials. By selecting residues according to their physical and chemical properties, the conversion of animal-based wastes into bioproducts can be optimised, enabling efficient, sustainable, and environmentally beneficial material development.

4.3. Effect of marine based bioresources properties on biomaterails

The elemental analysis shows that fish-derived wastes and microbial biomass, with moderate carbon (40–55%), hydrogen (5–8%), and relatively high nitrogen (8–14%), are well-suited for bioproducts such as biofertilizers, amino acid recovery, or microbial fermentation, though higher oxygen content limits energy applications. Fish scales and shells are more specialized: scales are oxygen-rich and low in carbon, favouring collagen or gelatin extraction rather than energy use, while shells provide chitin for biopolymer production but require processing. Sediments and detritus have variable carbon and low nitrogen, making them better as soil amendments than nutrient-rich feedstocks. In contrast, plastics (PE, PP, PET, nylon) are carbon-dense but lack balanced nutrients, making them unsuitable for direct bioproducts, though they hold potential for energy recovery or polymer recycling. Overall, biological wastes offer greater versatility and value for sustainable bioproduct generation compared to plastics.

4.4. Effect of microbial

Microbial-based bioresources generate diverse wastes from cultivation, fermentation, and downstream processing, including microbial biomass residues, spent culture media, and contaminated laboratory or packaging materials [

Table 7]. Physical properties vary considerably: microbial cell pellets are semi-solid, moist, and heterogeneous (60–80% moisture, 0.5–0.8 g/cm

3), ideal for bioproducts such as biofertilisers, biogas, or single-cell proteins. Dry, granular residues from spent media (<10% moisture, 0.4–0.6 g/cm

3) can be processed into biofuels or soil amendments. Fibrous insoluble residues from solid-state fermentation (20–40% moisture) support biocomposites or cellulose-based materials, while polymeric wastes such as plasticware, gloves, and packaging are lightweight and durable, requiring recycling or energy recovery due to limited biodegradability.

Chemical composition plays a crucial role in determining the suitability of microbial wastes for various biomaterials [

Table 13]. Biomass-rich residues contain high carbon (40–60%), hydrogen (5–8%), nitrogen (4–8%), and oxygen (25–45%), supporting nutrient- or energy-rich applications. Cellulose-rich wastes, such as cotton swabs and filter papers, provide polysaccharide substrates for bioethanol, organic acids, or biodegradable films. Plastic-rich wastes are polymeric with high carbon and hydrogen but negligible nitrogen and oxygen, making them more appropriate for recycling or energy recovery. Selecting microbial residues based on their moisture, density, and chemical composition allows them to be efficiently turned into useful products while saving resources and minimising environmental harm.

4.5. Effect of algal

Algal-based bioresources produce diverse wastes during cultivation, harvesting, and processing, including residual biomass after extraction of bioactive compounds, broken fronds, dewatered sludge, spent growth media solids, insoluble cell walls, and packaging materials [

Table 9]. Physical properties vary with type and processing stage: fresh biomass and harvesting residues are soft, cohesive, fibrous, and gelatinous (75–90% moisture, 0.6–0.9 g/cm

3, 20–35% porosity), requiring dewatering before use. Dewatered sludge is denser (0.9–1.1 g/cm

3) with lower porosity, suitable for pelletising or structured biomaterials, while partially dried cell walls and debris (20–50% moisture, 35–55% porosity) are granular or fibrous and ideal for composites, biofilms, or soil amendments. Settled biomass from spent media retains high moisture (70–85%) and medium–high density (0.8–1.05 g/cm

3), offering nutrient-rich substrates for bioprocessing [

21,

22].

Chemical composition strongly influences the suitability of algal residues for biomaterials. Microalgae such as Chlorella and Spirulina have high carbon (49–52%) and nitrogen (10–11%), with moderate hydrogen (6–7%) and low sulfur (0.55–0.60%), reflecting protein- and carbohydrate-rich biomass suitable for bioenergy, bioplastics, and biochemical applications [

51]. Other algal wastes, including residual biomass and macroalgae, exhibit lower carbon (5.8–44.9%) and nitrogen (0.68–7.4%) but higher oxygen (up to 54.85%), indicating structural polysaccharides remaining after extraction [

30]. The effectiveness of converting algal waste into biofuels, bioplastics, or composites depends on evaluating each species and its physical and chemical characteristics.

5. Recent advances in biomaterials production

Table 23 shows recent progress in making biomaterials from biowaste, including key developments, benefits, and challenges. Recent progress in the use of biowaste has shown strong potential to turn organic residues into useful biomaterials. Polyhydroxyalkanoates and other bio-based plastics are one clear example. In this method, mixed food and agricultural wastes can be fermented into lactic acid and used to grow Cupriavidus necator [

142]. Advances in modular bioprocesses have improved yields, providing a more sustainable option to replace fossil-based plastics while reducing organic waste disposal. The main difficulties, however, lie in variations in feedstock quality, high production costs, and the lack of clear compostability standards.

Nanocellulose and bio-based composites, mainly sourced from crop residues such as husks, stalks, and straw, have also seen important improvements. Better pretreatment and isolation methods, along with surface functionalisation, have enabled their use in packaging and structural materials [134. These materials are light, strong, and biodegradable, making them attractive alternatives to plastics. Their wider use is limited by the high energy required for pretreatment and challenges in managing the supply chain. Carbon-

Table 23.

Recent advances in biomaterials production from biowaste.

Table 23.

Recent advances in biomaterials production from biowaste.

| Bioproduct |

Biowaste source |

Key advances |

Benefits |

Challenges |

References |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and other bioplastics |

Food waste, agricultural residues |

Fermentation of heterogeneous waste streams (e.g., to lactic acid) feeding Cupriavidus necator; modular bioprocesses; higher yields |

Sustainable plastic alternatives, valorisation of organic waste |

Feedstock variability, scale-up costs, compostability standards |

[142] |

| Nanocellulose and bio-based composites |

Crop residues (straw, husks, stalks) |

Improved pretreatments and isolation; surface functionalisation; incorporation into composites |

Lightweight, high-strength, biodegradable packaging and structural materials |

High energy consumption in pretreatment; supply chain logistics |

[143] |

| Carbonaceous materials (biochar, activated carbon, nanocarbons) |

Agro-wastes, food residues, organic by-products |

Low-temperature pyrolysis; hybrid plasma-thermal methods; enhanced structural control |

Useful in adsorption, catalysis, energy storage |

Energy inputs, reproducibility, economic viability |

[144] |

| Chitosan, collagen, hydroxyapatite |

Shellfish shells, animal bones, hides |

Advanced extraction and purification; composite and coating development |

Biomedical, packaging and environmental applications |

Regulatory approval, batch consistency, cost of extraction |

[145] |

| Single-Cell Protein (SCP) |

Food/agro-waste, industrial by-products, syngas from waste |

Growth on lignocellulosic hydrolysates; metabolic engineering; “full gas” route (CO, CO2, H2 → protein); integrated biorefineries |

Sustainable alternative to soy/fishmeal

- High protein yield

- Can valorize diverse wastes |

High production cost

- Regulatory hurdles for food/feed safety

- Scale-up and consumer acceptance |

[146,147] |

| Biofuels & Platform Chemicals |

Lignocellulose, food waste, MSW, crude glycerol |

Pretreatment & hydrolysis improvements; syngas fermentation; metabolic engineering for organic acids/diols; biomass-derived catalysts |

Reduces reliance on fossil fuels

- Broad product range (ethanol, succinic acid, etc.)

- Integrates into circular bioeconomy |

Energy-intensive pretreatments

- Low yields with mixed wastes

- High separation/purification costs |

[148,149] |

| Mycelium-based composites and bio-designed materials |

Agricultural residues, paper waste, mixed organic waste |

Scalable cultivation on waste substrates; moulded panels and packaging |

Biodegradable foams, packaging, building materials |

Moisture resistance, durability |

[150,151] |

based materials such as biochar, activated carbon, and nanocarbons are also being made from agro-wastes and organic by-products. Low-temperature pyrolysis and plasma-thermal methods allow greater control of their structure, making them suitable for adsorption, catalysis, and energy storage [

135]. However, challenges related to energy demand, consistency, and cost still limit further development.

Biowaste streams also enable the extraction of biopolymers such as chitosan, collagen, and hydroxyapatite from shellfish shells, animal bones, and hides. Advanced purification techniques have improved their quality for use in biomedical, packaging, and environmental applications, though regulatory approval processes and batch consistency issues present barriers to market expansion [

145]. Another promising development is the production of single-cell protein (SCP) [

146,

147]. Using lignocellulosic hydrolysates, syngas, or industrial by-products, microbial processes have been engineered to produce protein through routes such as the conversion of CO, CO

2, and H

2 into biomass. This provides a sustainable alternative to soy and fishmeal. Despite its high protein yields and ability to use diverse wastes, SCP production faces high costs, strict food and feed safety rules, and uncertainty over consumer acceptance.

Biofuels and platform chemicals offer another route for biowaste use, helping to close loops in the circular bioeconomy. Advances in pretreatment, syngas fermentation, and microbial engineering now allow waste biomass to be converted into ethanol, succinic acid, and similar products. These processes cut dependence on fossil fuels and broaden the product base, but energy-intensive pretreatments, low yields from mixed wastes, and expensive separation steps remain challenges [

139,

140]. Mycelium-based composites are a more recent innovation, produced by growing fungi on agricultural residues and paper waste. They can be shaped into foams, packaging, and building panels, providing biodegradable and scalable alternatives to plastics. The main technical barriers are poor resistance to moisture, limited durability, and maintaining uniform production [

141,

142].

6. Future perspectives on sustainability and the circular bioeconomy

The future of sustainability in the circular bioeconomy is increasingly being shaped by the valorisation of biowaste into high-value biomaterials. Biomaterials such as biochar, bioactivated carbon, and catalytic materials are central to this approach. Biochar, derived from pyrolysis, gasification, or hydrothermal carbonisation of plant, animal, marine, or microbial residues, provides a carbon-rich, porous structure useful for soil amendment, energy storage, and catalysis, while by-products like syngas and bio-oil contribute to integrated energy systems [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Bioactivated carbon, produced via thermal, chemical, or combined activation, offers high surface area and functional groups suitable for adsorption, environmental remediation, and industrial applications [

60]. Catalytic biomaterials from biowaste, including eggshell-derived CaO and lignocellulosic biochar, demonstrate high efficiency in biodiesel production, pollutant degradation, and electrocatalysis, highlighting the dual environmental and economic benefits of biowaste valorisation [

70].

Dental, electroactive, extracellular matrix, and injectable biomaterials exemplify the biomedical potential of biowaste-derived products. Eggshell-derived hydroxyapatite, collagen-rich hydrogels, and starch-based nanocomposites provide biocompatible scaffolds for bone regeneration, wound healing, and controlled drug delivery [

87]. Similarly, electroactive biomaterials from fish scales, crustacean shells, and microbial residues enable energy harvesting, biosensing, and tissue engineering applications, combining renewable feedstocks with functional performance [

85,

86,

89]. Advanced smart biomaterials exploit stimuli-responsive features from algal polysaccharides, fruit peel extracts, and brewery spent grains, creating pH- or temperature-responsive films, hydrogels, and coatings for biomedical, packaging, and electronic applications [

115].

Biometals, bioplastics, and building biomaterials further illustrate circular bioeconomy strategies. Bioiron and biorutile processes leverage lignocellulosic residues for low-emission metallic production, while bioplastics such as PLA, PHA, and bio-PE, derived from sugarcane, corn, and other feedstocks, offer biodegradable alternatives to fossil-based polymers. Bio-bricks and bio-based e-textiles integrate lignin, agricultural residues, and cellulose into structural and wearable materials, supporting sustainable construction and electronics. Recent advances in biomaterials production, including polyhydroxyalkanoates, nanocellulose composites, carbon-based materials, and single-cell proteins, demonstrate the potential of biowaste to generate versatile, high-value products while addressing challenges related to feedstock variability, processing costs, and scalability [

143]. These developments show that using biowaste adds value while supporting sustainability, innovation, and a circular bioeconomy.

7. Conclusions