Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Graphene from Candlenut Shell Waste

2.2. Preparation of Test Microorganisms

2.3. MIC and MBC Assays

2.4. Cell Leakage Assay

2.5. Time-Kill Kinetics Assay

2.6. Antibiofilm Assay Using 96-Well Microplate

2.7. Antibiofilm Assay Using 6-Well Microplate

2.8. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MIC and MBC Values of GNPsCSW

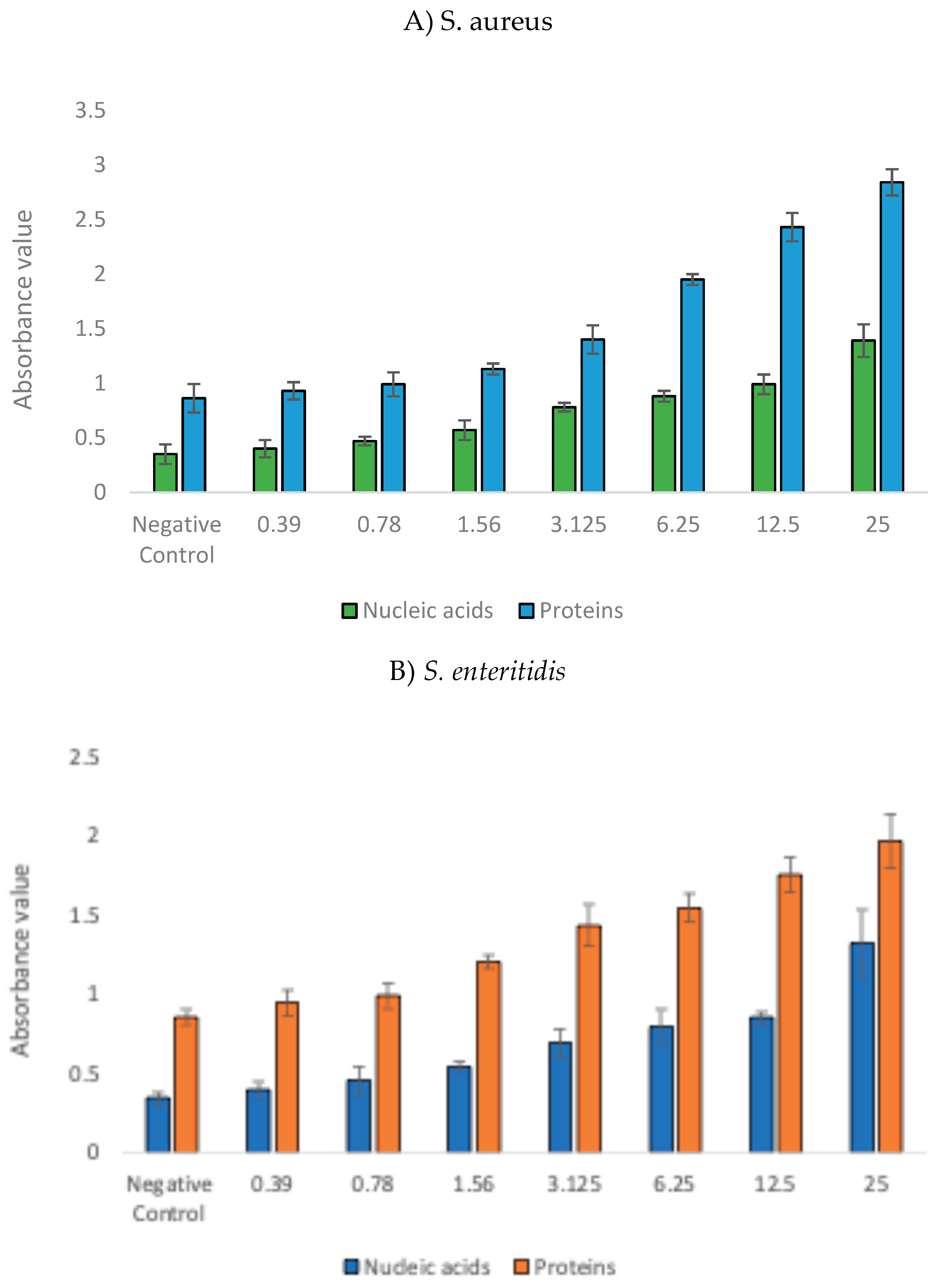

3.2. Bacterial Cell Leakage Following Treatment with GNPsCSW

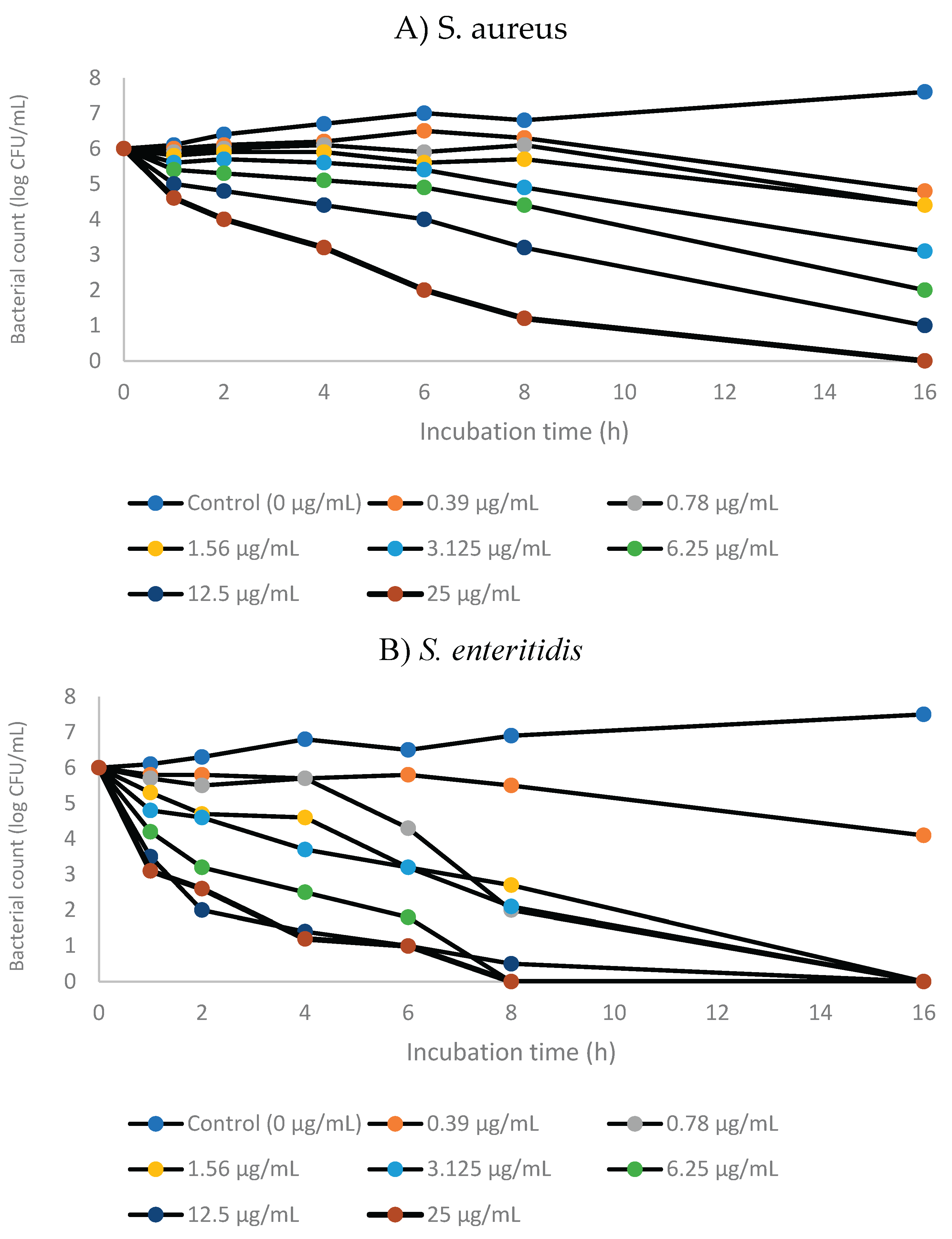

3.3. Time-Kill Kinetics of GNPsCSW

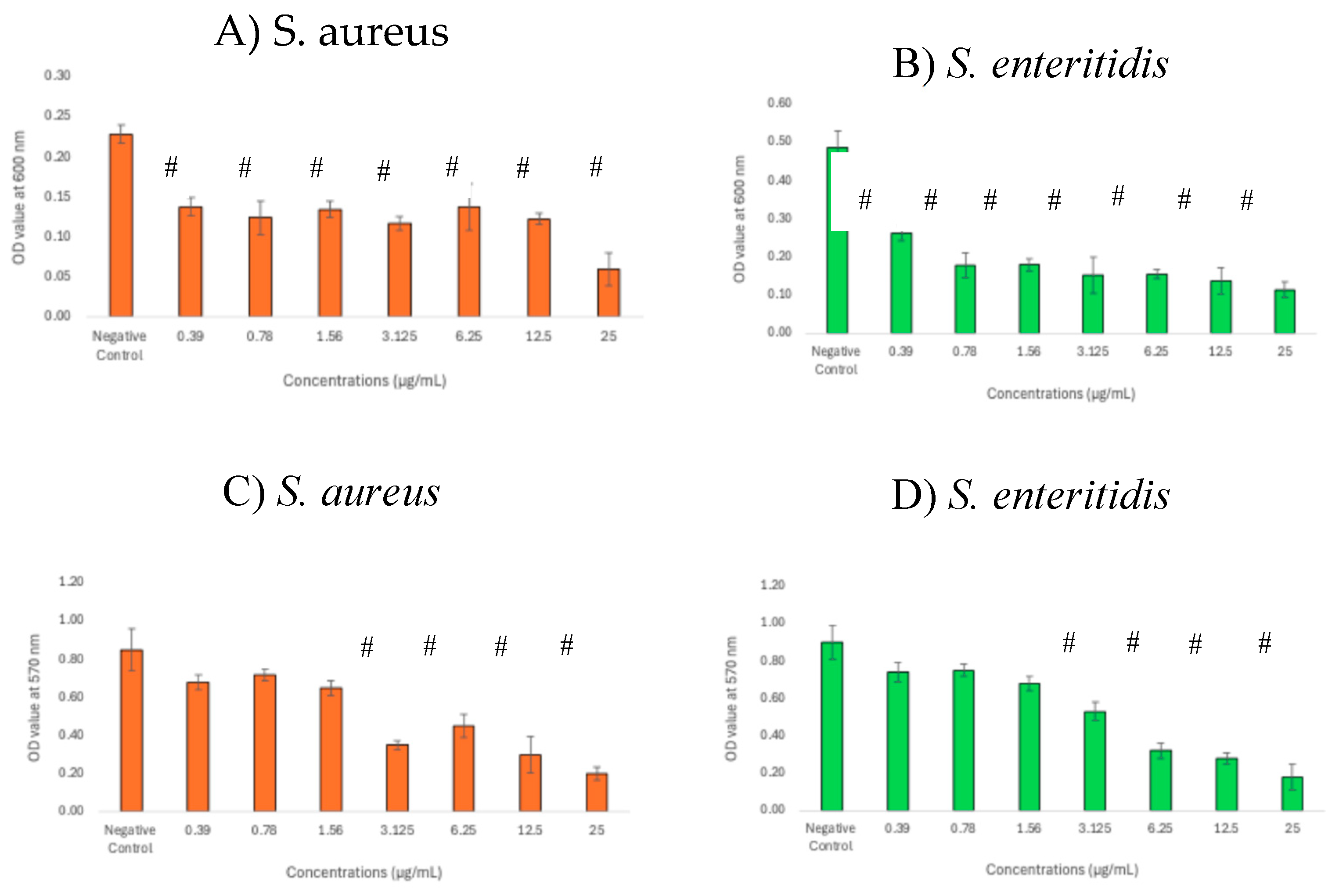

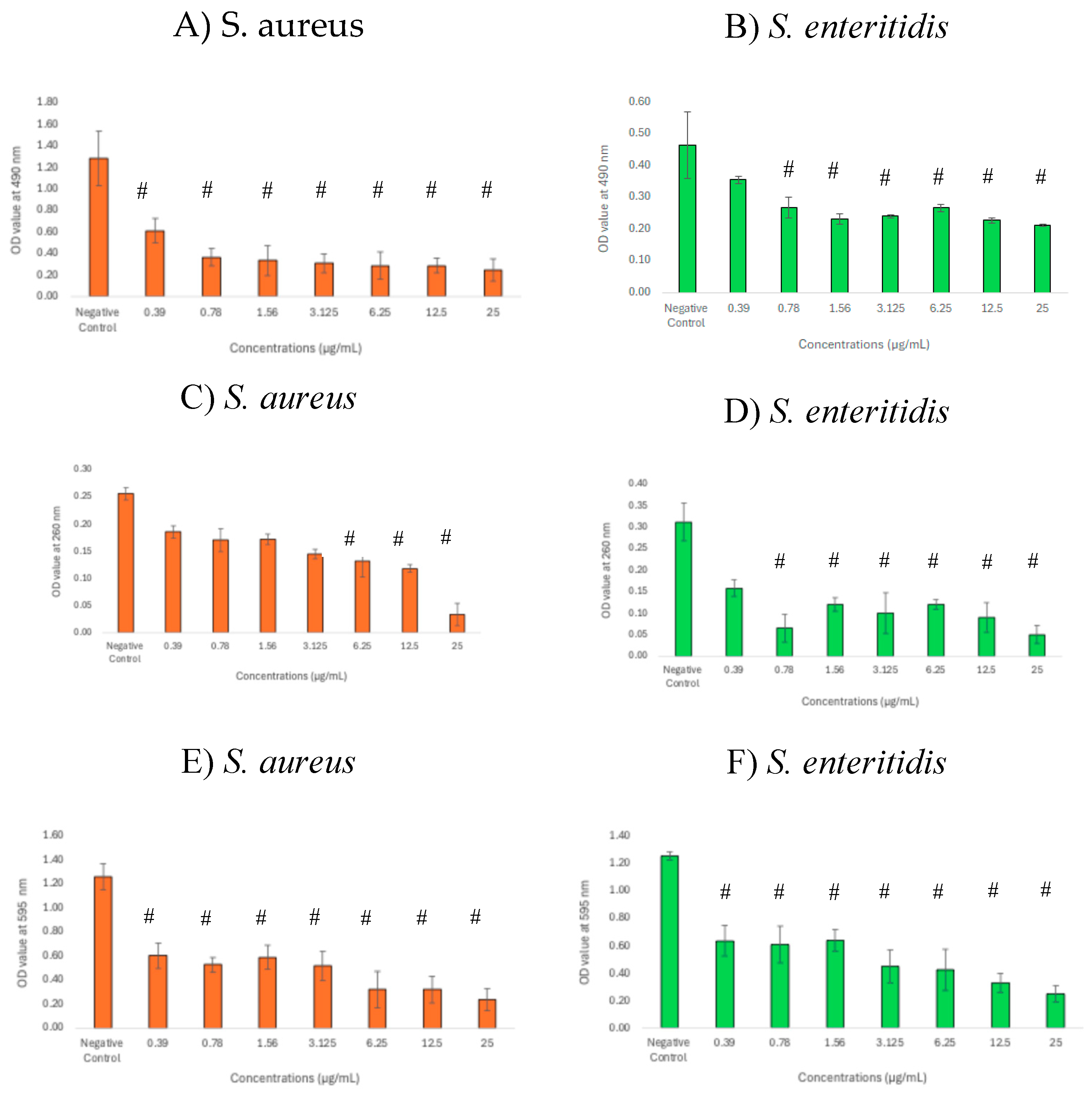

3.4. Inhibitory Effects of GNPsCSW on Biomass and Viability of Biofilms

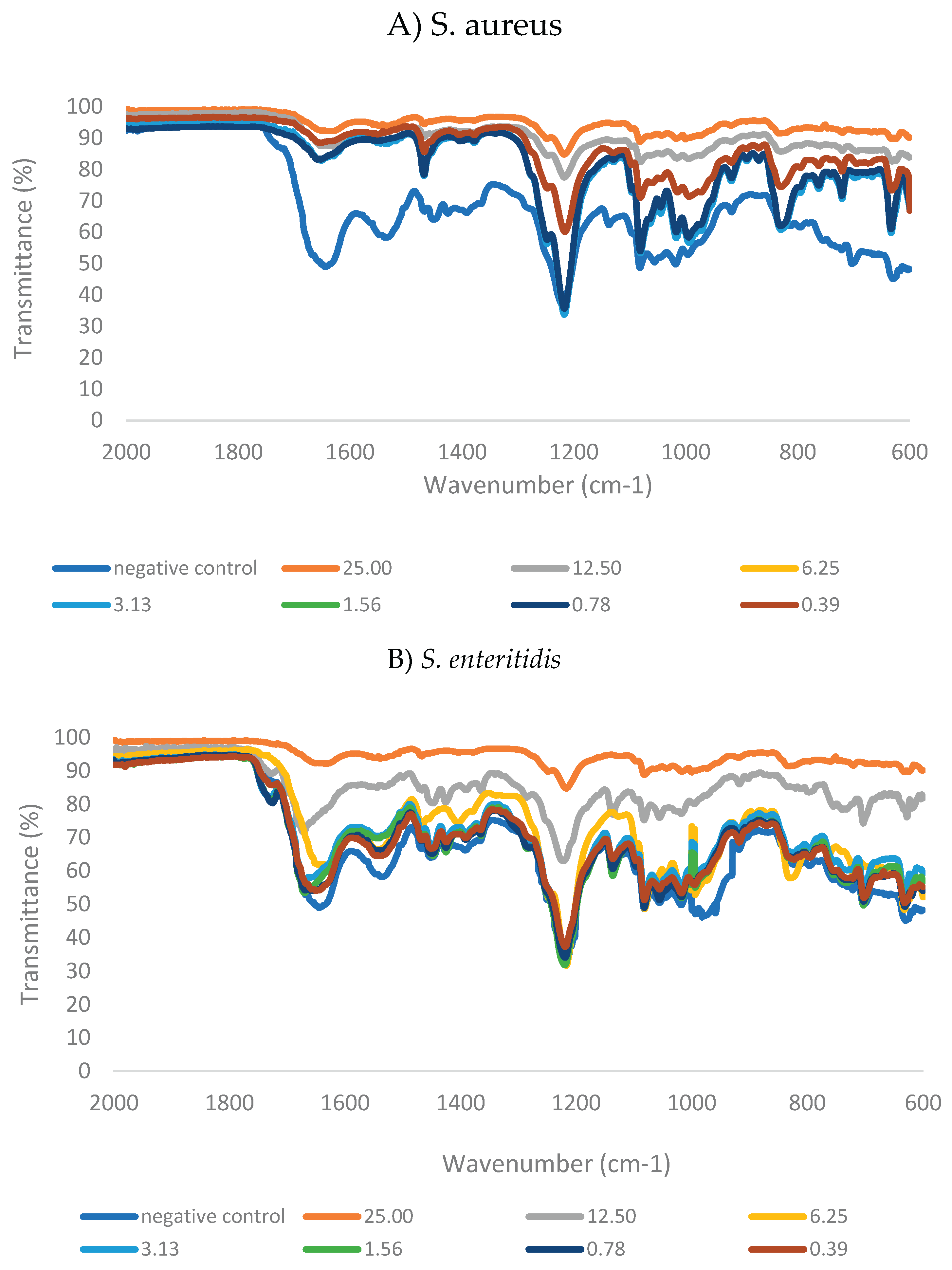

3.5. Structural Changes of Biofilms Following Treatment with GNPsCSW

3.6. Alteration of Biofilm Matrix Composition Following Treatment with GNPsCSW

3.7. Correlation Between Biofilm Biomass and Matrix Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GNPs | Graphene nanoparticles |

| GNPsCSW | Graphene nanoparticles synthesized from candlenut shell waste |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentraion |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared |

References

- Fathima, A., Arafath, Y., Hassan, S., Prathiviraj, R., Kiran, G. S., & Selvin, J. Microbial biofilms: A persisting public health challenge. In Understanding Microbial Biofilms 2023, (pp. 291–314).

- Malakar, C., Deka, S., & Kalita, M. C. Role of biosurfactants in biofilm prevention and disruption. In Advancements in Biosurfactants Research 2023 (pp. 481–501).

- Baishya, J., Everett, J. A., Chazin, W. J., Rumbaugh, K. P., & Wakeman, C. A. The innate immune protein calprotectin interacts with and encases biofilm communities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Scaffo, J., Lima, R., Dobrotka, C., Ribeiro, T., Pereira, R., Sachs, D., Ferreira, R., & Aguiar-Alves, F. In vitro analysis of interactions between Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa during biofilm formation. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 504. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Zhao, Y., Breslawec, A., Liang, T., Deng, Z., Kuperman, L., & Yu, Q. Strategy to combat biofilms: a focus on biofilm dispersal enzymes. NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes 2023, 9, 63. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Yin, R., Cheng, J., & Lin, J. Bacterial biofilm formation on biomaterials and approaches to its treatment and prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11680. [CrossRef]

- Shintawati, N., Widodo, Y., & Ermaya, D. Yield and quality improvement of candlenut oil by microwave assisted extraction (MAE) methods. IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1012(1), 012024.

- Hakim, A., Jamaluddin, J., Idrus, S. W. A., Jufri, A. W., & Ningsih, B. N. S. Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and biological activity review of Aleurites moluccana. J Appl Pharm Sci 2022, 12, 170–178. [CrossRef]

- Siburian, R., Tarigan, K., Manik, Y. G. O., Hutagalung, F., Alias, Y., Chan, Y. C., Chang, B. P., Siow, J., Ong, A. J., Huang, J., Paiman, S., Goh, B. T., Simatupang, L., Goei, R., Tok, A. I. Y., Yahya, M. F. Z. R., & Bahfie, F. Converting candlenut shell waste into graphene for electrode applications. Processes 2024, 12, 1544. [CrossRef]

- Lempang, M., Sallata, M. K., & Ansari, F. Modified drum kiln application to produce candlenut shell charcoal as alternative bioenergy. AIP Conference Proceedings 2025, 3285, 020003.

- Neto, A. C., Guinea, F., & Peres, N. M. Drawing conclusions from graphene. Physics World 2006, 19(11), 33–37. [CrossRef]

- Muthuvinayagam, M., Kumar, S. S. A., Ramesh, K., & Ramesh, S. Introduction of graphene: the “Mother” of all carbon allotropes. In Engineering materials 2023, (pp. 5–20).

- Kaur, H., Garg, R., Singh, S., Jana, A., Bathula, C., Kim, H., Kumbar, S. G., & Mittal, M. Progress and challenges of graphene and its congeners for biomedical applications. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 368, 120703. [CrossRef]

- Abdulqader, A. F., Salman, L. B., Nasr, Y. F., Bodnar, N., & Hikmat, R. Graphene based composites material characteristics and industrial uses. Radioelectronics Nanosystems Information Technologies 2024, 16, 605–616.

- Seifi, T., & Kamali, A. R. Anti-pathogenic activity of graphene nanomaterials: A review. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 199, 111509. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y., Lv, M., Xiu, P., Huynh, T., Zhang, M., Castelli, M., Liu, Z., Huang, Q., Fan, C., Fang, H., & Zhou, R. Destructive extraction of phospholipids from Escherichia coli membranes by graphene nanosheets. Nature Nanotechnology 2013, 8, 594–601. [CrossRef]

- Prema, D., Binu, N. M., Prakash, J., & Venkatasubbu, G. D. Photo induced mechanistic activity of GO/Zn(Cu)O nanocomposite against infectious pathogens: Potential application in wound healing. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2021, 34, 102291. [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M., Di Lodovico, S., Fontana, A., Traini, T., Di Campli, E., Pilato, S., D’Ercole, S., & Cellini, L. Graphene oxide affects Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa dual species biofilm in Lubbock chronic wound biofilm model. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 18525. [CrossRef]

- Er, S. G., Edirisinghe, M., & Tabish, T. A. Graphene--Based nanocomposites as antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal agents. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2023, 12, 2201523. [CrossRef]

- Pham, V. T. H., Truong, V. K., Quinn, M. D. J., Notley, S. M., Guo, Y., Baulin, V. A., Kobaisi, M. A., Crawford, R. J., & Ivanova, E. P. Graphene induces formation of pores that kill spherical and Rod-shaped bacteria. ACS Nano 2015, 9(8), 8458–8467. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A. L. T., Farrag, H. N., Sabidi, S., Kato, T., Maeda, T., & Andou, Y. Accessing the anti-microbial activity of cyclic peptide immobilized on reduced graphene oxide. Materials Letters 2021, 304, 130621. [CrossRef]

- Amran, S.S.D., Jalil, M.T.M., Aziz, A.A., Yahya, M.F.Z.R.Y. Methanolic extract of Swietenia macrophylla exhibits antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy against Gram-positive pathogens. Malaysian Applied Biology 2023, 52, 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Shehabeldine, A.M., Amin, B.H., Hagras, F.A. Potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties of copper oxide nanoparticles: Time-kill kinetic essay and ultrastructure of pathogenic bacterial cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2023, 195, 467–485. [CrossRef]

- Caso Coelho, V., Pereira Neves, S. D. A., CintraGiudice, M., Benard, G., Lopes, M. H., & Sato, P. K. Evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Nocardia spp. isolates by broth microdilution with resazurin and spectrophotometry. BMC Microbiology 2021, 21, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hasanin, M., Elbahnasawy, M. A., Shehabeldine, A. M., & Hashem, A. H. Ecofriendly preparation of silver nanoparticles-based nanocomposite stabilized by polysaccharides with antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activities. BioMetals 2021, 34, 1313–1328. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I., Yahya, M.F.Z.R., Bakar, L.M., Zakaria, N.A., Ibrahim, D. & Mat Jalil, M.T. Efficacy of Terminalia catappa leaves extract as an antimicrobial agent against pathogenic bacteria. Malaysian Applied Biology 2024, 53, 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Okba, M. M., Baki, P. M. A., Abu-Elghait, M., Shehabeldine, A. M., El-Sherei, M. M., Khaleel, A. E., & Salem, M. A. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS profiling of the underground parts of common Iris species in relation to their anti-virulence activities against Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 282, 114658. [CrossRef]

- Amran, S. S. D., Syaida, A. A. R., Jalil, M. T.M., Nor, N. H. M., & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. Preparation of biofilm assay using 96-well and 6-well microplates for quantitative measurement and structural characterization: A review. Science Letters 2024. 18. 121-134.

- Johari, N. A., Aazmi, M. S., & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. FTIR spectroscopic study of inhibition of chloroxylenol-based disinfectant against Salmonella enterica serovar Thyphimurium biofilm. Malaysian Applied Biology 2023, 52(2), 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M. F. Z. R., Alias, Z., & Karsani, S. A. Antibiofilm activity and mode of action of DMSO alone and its combination with afatinib against Gram-negative pathogens. Folia Microbiologica 2018, 63(1), 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D., Tiwari, M., & Tiwari, V. Molecular mechanism of antimicrobial activity of chlorhexidine against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. PloS one 2019, 14(10), e0224107. [CrossRef]

- DeQueiroz, G. A., & Day, D. F. Antimicrobial activity and effectiveness of a combination of sodium hypochlorite and hydrogen peroxide in killing and removing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms from surfaces. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2007, 103(4), 794-802. [CrossRef]

- Duan, G., Zhang, Y., Luan, B., Weber, J. K., Zhou, R. W., Yang, Z., ... & Zhou, R. Graphene-induced pore formation on cell membranes. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 42767. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y., Lv, M., Xiu, P., Huynh, T., Zhang, M., Castelli, M., ... & Zhou, R. Destructive extraction of phospholipids from Escherichia coli membranes by graphene nanosheets. Nature nanotechnology 2013, 8(8), 594-601. [CrossRef]

- Lundstedt, E., Kahne, D., & Ruiz, N. Assembly and maintenance of lipids at the bacterial outer membrane. Chemical reviews 2020, 121(9), 5098-5123. [CrossRef]

- Tan, K. H., Sattari, S., Beyranvand, S., Faghani, A., Ludwig, K., Schwibbert, K., ... & Adeli, M. Thermoresponsive amphiphilic functionalization of thermally reduced graphene oxide to study graphene/bacteria hydrophobic interactions. Langmuir 2019, 35(13), 4736-4746. [CrossRef]

- Karaky, N., Tang, S., Ramalingam, P., Kirby, A., McBain, A. J., Banks, C. E., & Whitehead, K. A. Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Remains Susceptible to Metal Ions and Graphene-Based Compounds. Antibiotics 2024, 13(5), 381. [CrossRef]

- Wong, F., Stokes, J. M., Cervantes, B., Penkov, S., Friedrichs, J., Renner, L. D., & Collins, J. J. Cytoplasmic condensation induced by membrane damage is associated with antibiotic lethality. Nature communications 2021, 12(1), 2321. [CrossRef]

- Elbasuney, S., Yehia, M., Ismael, S., Al-Hazmi, N. E., El-Sayyad, G. S., & Tantawy, H. Potential impact of reduced graphene oxide incorporated metal oxide nanocomposites as antimicrobial, and antibiofilm agents against pathogenic microbes: Bacterial protein leakage reaction mechanism. Journal of Cluster Science 2023, 34(2), 823-840. [CrossRef]

- Vaddady, P. K., Lee, R. E., & Meibohm, B. In vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models in anti-infective drug development: focus on TB. Future Medicinal Chemistry 2010, 2(8), 1355-1369. [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, A. C. M., Lima, B. A., de Faria, A. F., Brocchi, M., & Alves, O. L. Graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite as a promising biocidal agent against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2015, 6847-6861. [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M. F. Z. R., Jalil, M. T. M., Jamil, N. M., Nor, N. H. M., Alhajj, N., Siburian, R., & Majid, N. A. Biofilms and multidrug resistance: an emerging crisis and the need for multidisciplinary interventions. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2025, 13, 1625356. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, V., Vidhawan, A. S., Seneviratne, C. J., & Silikas, N. Graphene nanocoating inhibits cross-kingdom biofilms on titanium. Dental Materials 2023, 39, e61. [CrossRef]

- Kamaruzzaman, A. N. A., Mulok, T. E. T. Z., & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. Inhibitory action of topical antifungal creams against Candida albicans biofilm. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management 2022, 17(2), 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Nag, M., Lahiri, D., Banerjee, R., Chatterjee, A., Ghosh, A., Banerjee, P., & Ray, R. R. Analysing Microbial Biofilm Formation at a Molecular Level: Role of Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy 2021. In Analytical Methodologies for Biofilm Research (pp. 69-93). New York, NY: Springer US.

- Abriat, C., Gazil, O., Heuzey, M. C., Daigle, F., & Virgilio, N. The polymeric matrix composition of Vibrio cholerae biofilms modulate resistance to silver nanoparticles prepared by hydrothermal synthesis. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13(30), 35356-35364. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, S., & Khan, A. U. Nanoparticles vs. biofilms: a battle against another paradigm of antibiotic resistance. MedChemComm 2016, 7(8), 1479-1498. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., Yang, K., Vachet, R. W., & Xing, B. Interaction between oxide nanoparticles and biomolecules of the bacterial cell envelope as examined by infrared spectroscopy. Langmuir 2010, 26(23), 18071-18077. [CrossRef]

- Sportelli, M. C., Tütüncü, E., Picca, R. A., Valentini, M., Valentini, A., Kranz, C., ... & Cioffi, N. Inhibiting P. fluorescens biofilms with fluoropolymer-embedded silver nanoparticles: an in-situ spectroscopic study. Scientific reports 2017, 7(1), 11870. [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Ryu, J., Jung, J., Yu, Y., Choi, S., & Kweon, J. Dispersive biofilm from membrane bioreactor strains: effects of diffusible signal factor addition and characterization by dispersion index. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1211761. [CrossRef]

- Joos, M., Van Ginneken, S., Villanueva, X., Dijkmans, M., Coppola, G. A., Pérez-Romero, C. A., ... & Steenackers, H. P. EPS inhibitor treatment of Salmonella impacts evolution without selecting for resistance to biofilm inhibition. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2025, 11(1), 73. [CrossRef]

| Pathogens | MIC (µg/mL) | MBC(µg/mL) | MBC/MIC index |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 12.5 | 25 | 2 |

| S. enteritidis | 6.25 | 12.5 | 2 |

| Relationships | S. aureus | S. enteritidis |

|---|---|---|

| B-C | 0.877 | 0.971 |

| B-NA | 0.924 | 0.966 |

| B-P | 0.902 | 0.962 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).