Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

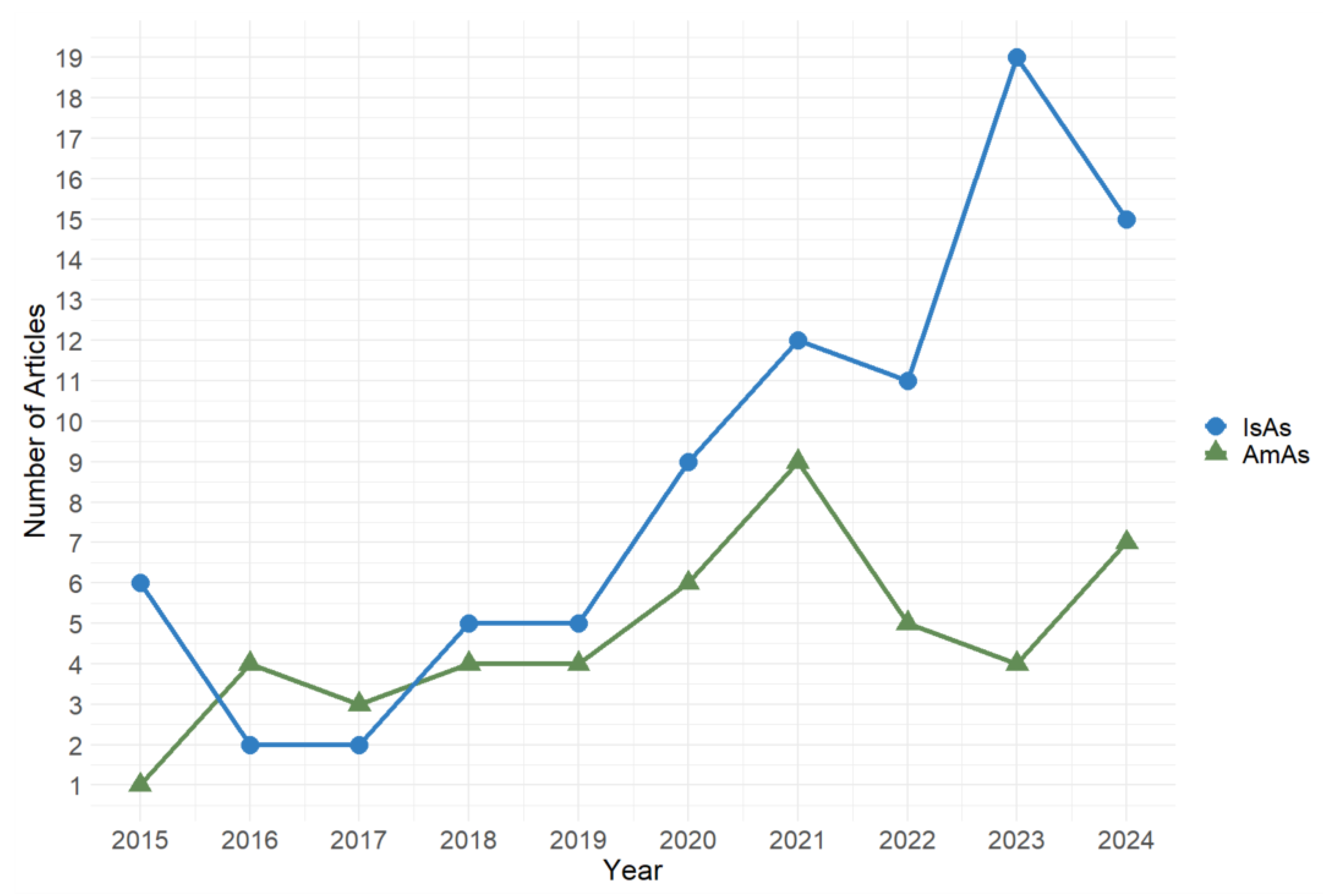

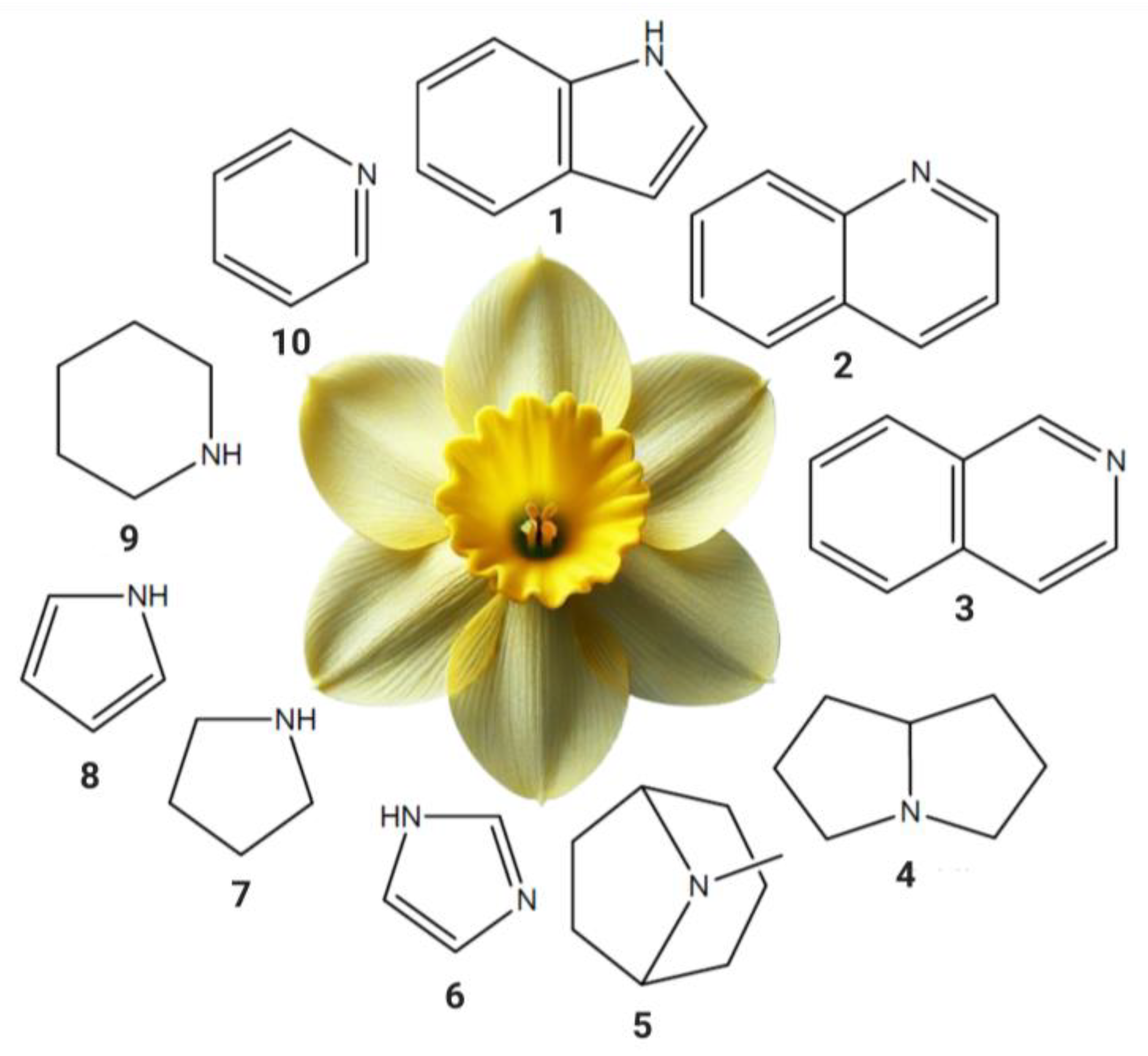

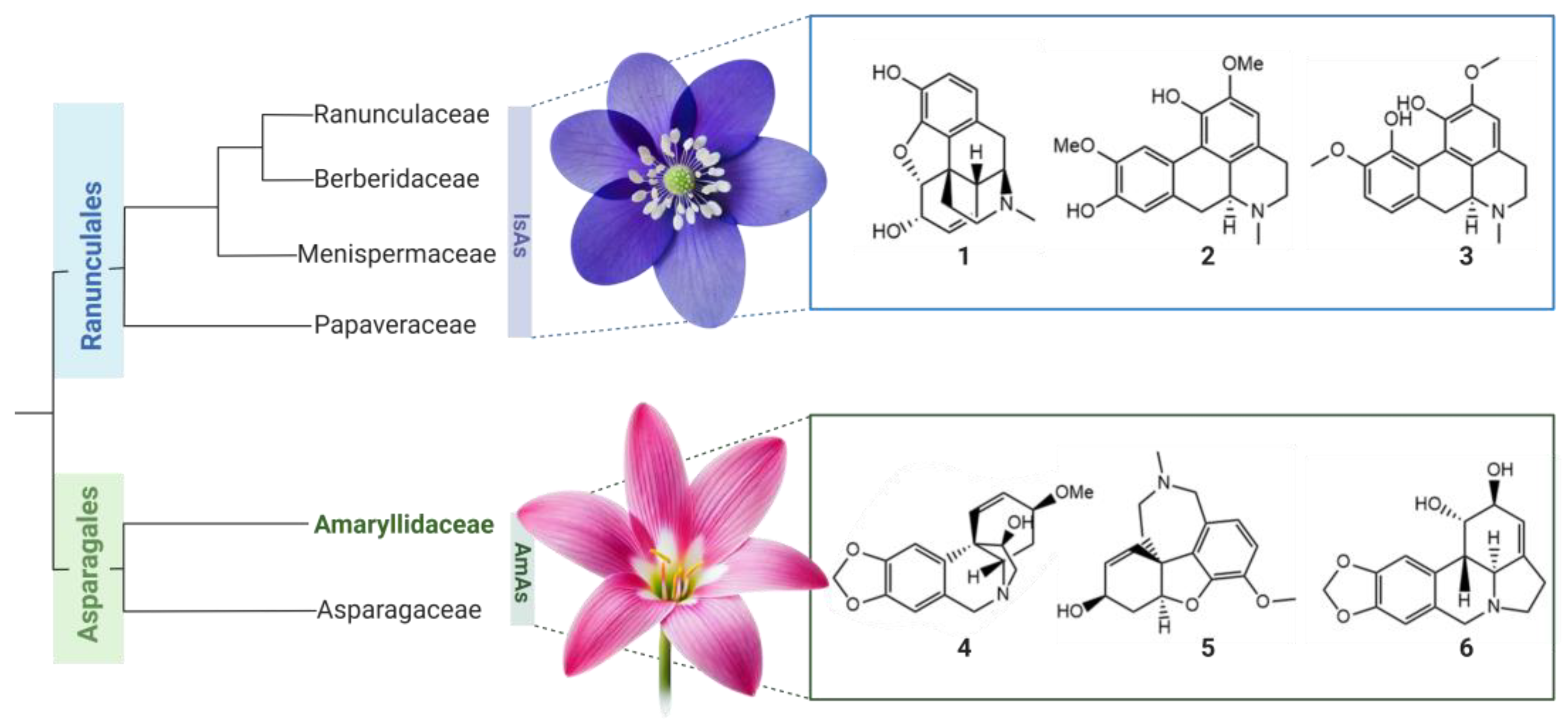

1. Introduction

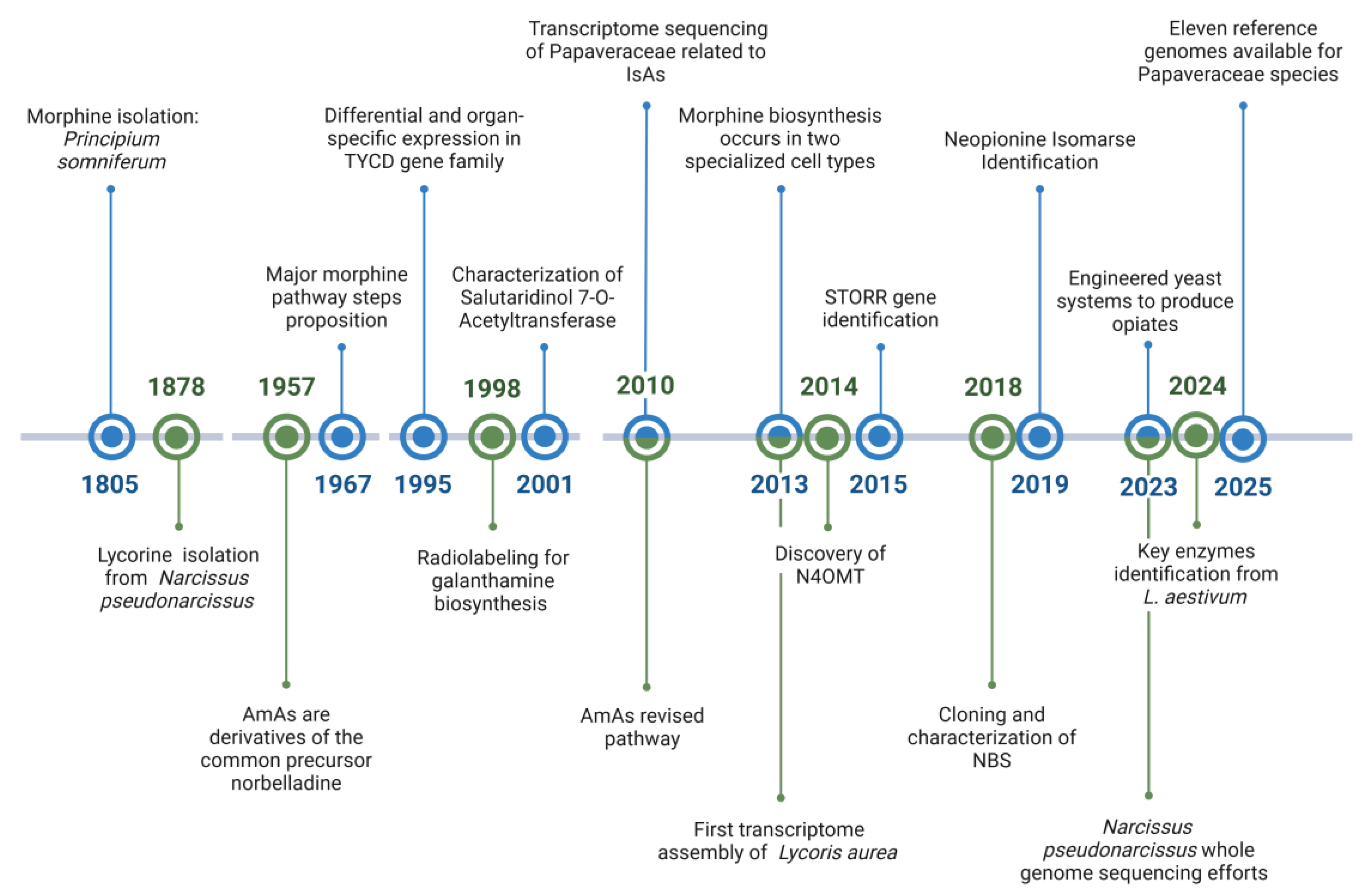

2. Historical Landmarks in IsAs and AmAs Pathway Elucidation

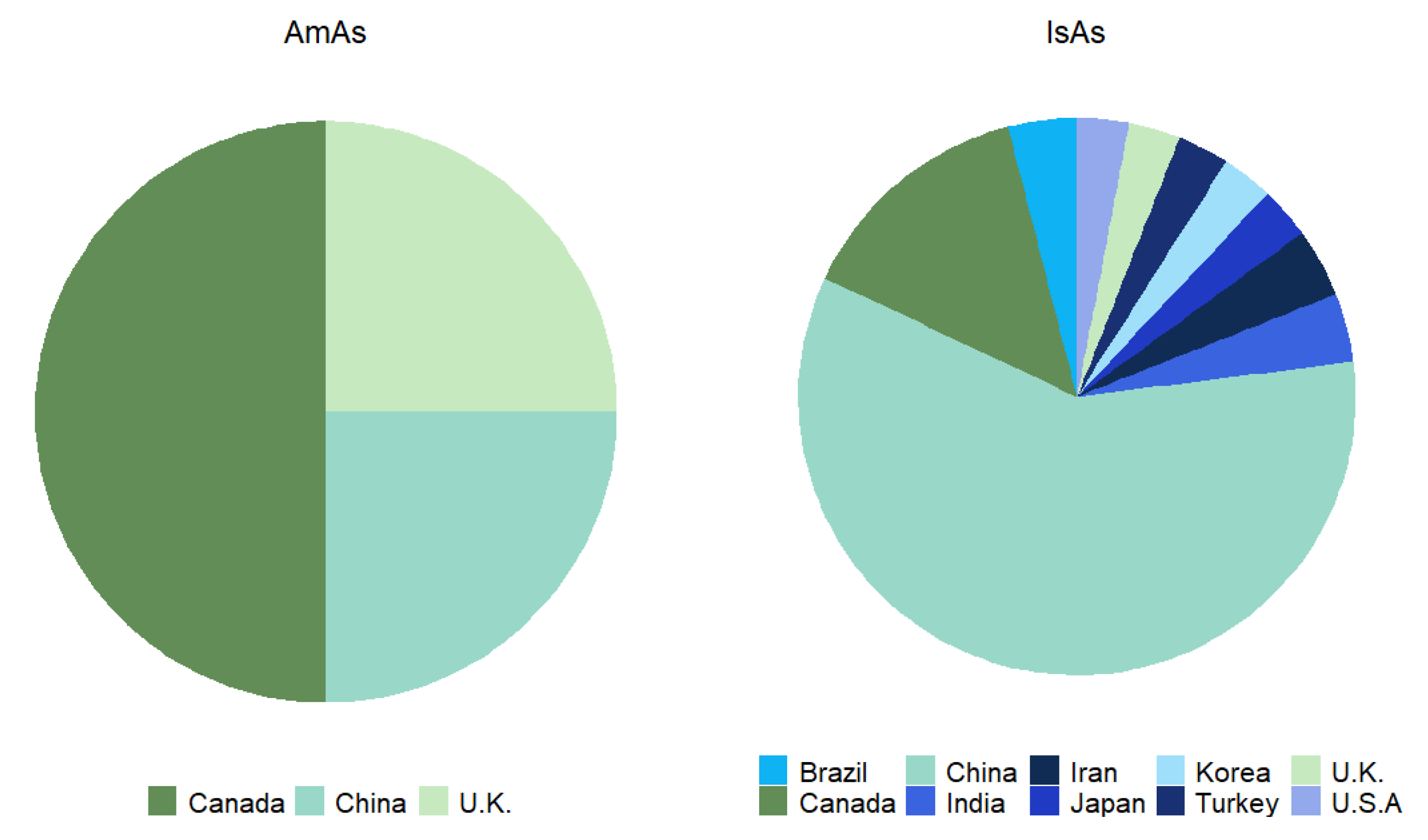

2.1. Mining Functional Genes on IsAs Biosynthesis

2.2. Mining Functional Genes on AmAs Biosynthesis

| Amaryllidaceae species | Sequencing year | Sequencing country | Sequencing platforms |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crinum x powellii | 2023 | Canada | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | [125] |

|

Leucojum aestivum |

2022 | Canada | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [126] |

|

Lycoris aurea |

2013 | China | 454 GS FLX | [123] |

| 2016 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [127] | |

| 2016 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [128] | |

| 2017 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [129] | |

| 2024 | China | Illumina HiSeq X Ten | [130] | |

|

Lycoris chinensis |

2022 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [131] |

|

Lycoris longituba |

2020 | China | Illumina HiSeq X Ten | [132] |

| 2021 | China | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | [119] | |

|

Lycoris radiata |

2019 | China | Illumina NextSeq 500 | [133] |

| Narcissus cyclamineus | 2024 | USA | Illumina HiSeq 4000/PacBio Iso-Seq | [46] |

| Narcissus papyraceus | 2019 | Canada | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [134] |

| Narcissus pseudonarcissus | 2017 | Canada | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [135] |

| 2021 | U.K. | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [136] |

3. Integrative Approaches on Biosynthetic Understanding

4. Challenges and Opportunities

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoffmann, D. Medical Herbalism: The Science Principles and Practices Of Herbal Medicine; 1st ed.; Healing Arts Press: Rochester, Vt, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Seigler, D.S. Plant Secondary Metabolism; Springer US, 1998;

- Hussein, R.A.; El-Anssary, A.A. Plants Secondary Metabolites: The Key Drivers of the Pharmacological Actions of Medicinal Plants. In Herbal Medicine; Builders, P.F., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2019.

- Taylor, S.L.; Hefle, S.L. Naturally Occurring Toxicants in Foods. In Foodborne Diseases (Third Edition); et al., C.E.R.D., Ed.; Academic Press, 2017; pp. 327–344.

- Pallardy, S.G. Chapter 9 - Nitrogen Metabolism. In Physiology of Woody Plants (Third Edition); Academic Press, 2008; pp. 233–254.

- Rajput, A.; Sharma, R.; Bharti, R. Pharmacological Activities and Toxicities of Alkaloids on Human Health. Mater Today Proc 2022, 48, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawabteh, A.; Juma, S.; Bader, M.; Karaman, D.; Scrano, L.; Bufo, S.A.; Karaman, R. The Biological Activity of Natural Alkaloids against Herbivores, Cancerous Cells and Pathogens. Toxins 2019, Vol. 11, Page 656 2019, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, Z.; Blythe, L.L.; Milella, L.; Bufo, S.A. Biological Activities of Alkaloids: From Toxicology to Pharmacology. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.R.; Vaz, N.P. Isoquinoline Alkaloids and Chemotaxonomy. 2019, 167–193. [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; et al. Chapter 15 - Analysis of Alkaloids (Indole Alkaloids, Isoquinoline Alkaloids, Tropane Alkaloids). In Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis; et al., A.S.S., Ed.; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 505–567.

- Bozarth, M. Dopamine. In; 2017; pp. 1173–1177.

- Samanani, N.; Facchini, P.J. Purification and Characterization of Norcoclaurine Synthase: THE FIRST COMMITTED ENZYME IN BENZYLISOQUINOLINE ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN PLANTS. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 33878–33883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoyovwe, A.; Hagel, J.M.; Chen, X.; Khan, M.F.; Schriemer, D.C.; Facchini, P.J. Morphine Biosynthesis in Opium Poppy Involves Two Cell Types: Sieve Elements and Laticifers. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.A.; Maeda, H.A. Tyrosine Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Catabolism in Plants. Phytochemistry 2018, 149, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Xu, X.-H. Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Ramawat, K.G., Mérillon, J.-M., Eds.; Springer, 2013; pp. 479–522.

- Bastida, J.; Berkov, S.; Torras Claveria, L.; Pigni, N.B.; Andrade, J.P.; Martínez, V.; Codina Mahrer, C.; Viladomat Meya, F. Chemical and Biological Aspects of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. In Recent Advances in Pharmaceutical Sciences; Elsevier, 2011; pp. 65–100.

- Berkov, S.; Osorio, E.; Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J. Chemodiversity, Chemotaxonomy and Chemoecology of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Knölker, H.-J., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 83, pp. 113–185.

- Dey, A.; Mukherjee, A. Chapter 6 - Plant-Derived Alkaloids: A Promising Window for Neuroprotective Drug Discovery. In Discovery and Development of Neuroprotective Agents from Natural Products; Brahmachari, G., Ed.; Elsevier (Natural Product Drug Discovery), 2018; pp. 237–320.

- Marco, L.; do Carmo Carreiras, M. Galanthamine, a Natural Product for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov 2006, 1, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kausar, S.; Mustafa, H.G.; Altaf, A.A.; Mustafa, G.; Badshah, A. ; others Galantamine. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences; Elsevier, 2019.

- Lamoral-Theys, D.; Andolfi, A.; Van Goietsenoven, G.; Cimmino, A.; Le Calvé, B.; Wauthoz, N.; Mégalizzi, V.; Gras, T.; Bruyère, C.; Dubois, J.; et al. Lycorine, the Main Phenanthridine Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid, Exhibits Significant Antitumor Activity in Cancer Cells That Display Resistance to Proapoptotic Stimuli: An Investigation of Structure−Activity Relationship and Mechanistic Insight. ACS Publications 2009, 52, 6244–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ka, S.; Masi, M.; Merindol, N.; Di Lecce, R.; Plourde, M.B.; Seck, M.; Górecki, M.; Pescitelli, G.; Desgagne-Penix, I.; Evidente, A. Gigantelline, Gigantellinine and Gigancrinine, Cherylline- and Crinine-Type Alkaloids Isolated from Crinum Jagus with Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Activity. Phytochemistry 2020, 175, 112390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.; Pidaný, F.; Hulcová, D.; Maříková, J.; Kučera, T.; Schmidt, M.; Catapano, M.C.; Hrabinová, M.; Jun, D.; Múčková, L.; et al. Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids of Norbelladine-Type as Inspiration for Development of Highly Selective Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Synthesis, Biological Activity Evaluation, and Docking Studies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagné-Penix, I. Biosynthesis of Alkaloids in Amaryllidaceae Plants: A Review. Phytochemistry Reviews 2021, 20, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Tallini, L.R.; Salazar, C.; Osorio, E.H.; Montero, E.; Bastida, J.; Oleas, N.H.; Acosta León, K. Chemical Profiling and Cholinesterase Inhibitory Activity of Five Phaedranassa Herb. (Amaryllidaceae) Species from Ecuador. Molecules 2020, 25, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiev, V.; Ivanov, I.; Pavlov, A. Recent Progress in Amaryllidaceae Biotechnology. Molecules 2020, 25, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, C.; Rao, S.C. The Isolation of Morphine by Serturner. Indian J Anaesth 2016, 60, 861–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, G.W. Biosynthesis of the Morphine Alkaloids. Science (1979) 1967, 155, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueffer, M.; El-Shagi, H.; Nagakura, N.; H Zenk, M. (S)-Norlaudanosoline Synthase: The First Enzyme in the Benzylisoquinoline Biosynthetic Pathway. FEBS Lett 1981, 129, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, S.; Stadler, R.; Nagakura, N.; Zenk, M.H. Norcoclaurine as Biosynthetic Precursor of Thebaine and Morphine. J Chem Soc Chem Commun 1987, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini’, P.J.; De Luca, V. Phloem-Specific Expression of Tyrosine/Dopa Decarboxylase Genes and the Biosynthesis of Isoquinoline Alkaloids in Opium Poppy. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1811–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothe, T.; Lenz, R.; Kutchan, T.M. Molecular Characterization of the Salutaridinol 7-O-Acetyltransferase Involved in Morphine Biosynthesis in Opium Poppy Papaver Somniferum. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 30717–30723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winzer, T.; Kern, M.; King, A.J.; Larson, T.R.; Teodor, R.I.; Donninger, S.L.; Li, Y.; Dowle, A.A.; Cartwright, J.; Bates, R.; et al. Plant Science. Morphinan Biosynthesis in Opium Poppy Requires a P450-Oxidoreductase Fusion Protein. Science 2015, 349, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastmalchi, M.; Chen, X.; Hagel, J.M.; Chang, L.; Chen, R.; Ramasamy, S.; Yeaman, S.; Facchini, P.J. Neopinone Isomerase Is Involved in Codeine and Morphine Biosynthesis in Opium Poppy. Nature Chemical Biology 2019 15:4 2019, 15, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L. Evaluation of Biosynthetic Pathway and Engineered Biosynthesis of Morphine with CRISPR. BIO Web Conf 2023, 59, 01022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narcross, L.; Pyne, M.E.; Kevvai, K.; Siu, K.-H.; Dueber, J.E.; Martin, V.J.J. Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Production in Yeast via Norlaudanosoline Improves Selectivity and Yield. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.05.19.541502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozber, N.; Yu, L.; Hagel, J.M.; Facchini, P.J. Strong Feedback Inhibition of Key Enzymes in the Morphine Biosynthetic Pathway from Opium Poppy Detectable in Engineered Yeast. ACS Chem Biol 2023, 18, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, A.W. The Proximate Principles of the Narcissus Pseudonarcissus. The pharmaceutical journal and transactions. Soc. 1878, 214–215. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D.; Cohen, T. Some Biogenetic Aspects of Phenol Oxidation. In Festschrift Prof Dr Arthur Stoll; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, 1957; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn, J.; Takada, T.; Kita, Y.; Zenk, M.H. Biosynthesis of the Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Galanthamine. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tahchy, A.; Boisbrun, M.; Ptak, A.; Dupire, F.; Chrétien, F.; Henry, M.; Chapleur, Y.; Laurain-Mattar, D. New Method for the Study of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Biosynthesis Using Biotransformation of Deuterium-Labeled Precursor in Tissue Cultures. Acta Biochim Pol. 2010, 57, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, M.B.; Augustin, M.M.; Starks, C.M.; O’Neil-Johnson, M.; May, G.D., C. J.A.; Kutchan, T.M. Cloning and Characterization of a Norbelladine 4′-O-Methyltransferase Involved in the Biosynthesis of the Alzheimer’s Drug Galanthamine in Narcissus Sp. Aff. Pseudonarcissus. PLoS One 2014, 9, e103223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Massicotte, M.A.; Garand, A.; Tousignant, L.; Ouellette, V.; Bérubé, G.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Cloning and Characterization of Norbelladine Synthase Catalyzing the First Committed Reaction in Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, B.B.; Gélinas, S.E.; Mérindol, N.; Ricard, S.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Characterization of Norbelladine Synthase and Noroxomaritidine/Norcraugsodine Reductase Reveals a Novel Catalytic Route for the Biosynthesis of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids Including the Alzheimer’s Drug Galanthamine. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilgore, M.B.; Augustin, M.M.; May, G.D.; Crow, J.A.; Kutchan, T.M. CYP96T1 of Narcissus Sp. Aff. Pseudonarcissus Catalyzes Formation of the Para-Para’ C-C Phenol Couple in the Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.; Meng, Y.; Zare, R.; Kamenetsky-Goldstein, R.; Sattely, E. A Developmental Gradient Reveals Biosynthetic Pathways to Eukaryotic Toxins in Monocot Geophytes. Cell 2024, 187, 5620–5637.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagne-Penix, I. Elucidating the Enzyme Network Driving Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids Biosynthesis. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.D.; Fales, H.M.; Mudd, S.H. Alkaloids and Plant Metabolism: VI. O-METHYLATION IN VITRO OF NORBELLADINE, A PRECURSOR OF AMARYLLIDACEAE ALKALOIDS. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1963, 238, 3820–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, M.E.; Martin, V.J.J. Microbial Synthesis of Natural, Semisynthetic, and New-to-Nature Tetrahydroisoquinoline Alkaloids. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2022, 33, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Gu, M. Transcriptome Analysis and Differential Gene Expression Profiling of Two Contrasting Quinoa Genotypes in Response to Salt Stress. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen Y; Wu D; Du Y; Wang M; Liu C; Chu J; Yao X Transcriptome Analysis Reveals an Essential Role of Exogenous Brassinolide on the Alkaloid Biosynthesis Pathway in Pinellia Ternata. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong Y; Wang L; Ma Z; Du X Physiological Responses and Transcriptome Analysis of Spirodela Polyrhiza under Red, Blue, and White Light. Planta 2021, 255, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, P.; Qian, C.; Zhao, X.; Xu, H.; Li, K. The Combined Analysis of the Transcriptome and Metabolome Revealed the Possible Mechanism of Flower Bud Formation in Amorphophallus Bulbifer. Agronomy 2024, 14, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen C; Shi X; Zhou T.; Li W; Li S; Bai G Full-Length Transcriptome Analysis and Identification of Genes Involved in Asarinin and Aristolochic Acid Biosynthesis in Medicinal Plant Asarum Sieboldii. Genome 2021, 64, 639–653. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui X; Meng F; Pan X; Qiu X; Zhang S; Li C; Lu S Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Aristolochia Contorta Provides Insights into the Biosynthesis of Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids and Aristolochic Acids. Hortic Res 2022, 9, uhac005. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M; Ren Y; Li, Z. Transcriptome Profiling of Jerusalem Artichoke Seedlings (Helianthus Tuberosus L.) under Polyethylene Glycol-Simulated Drought Stress. Ind Crops Prod 2021, 170, 113696. [CrossRef]

- Farrow, S.C.; Hagel, J.M.; Facchini, P.J. Transcript and Metabolite Profiling in Cell Cultures of 18 Plant Species That Produce Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids. Phytochemistry 2012, 77, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J. V; Dalisay, D.S.; Yang, H.; Lee, C.; Davin, L.B.; Lewis, N.G. A Multi-Omics Strategy Resolves the Elusive Nature of Alkaloids in Podophyllum Species. Mol Biosyst 2014, 10, 2838–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagel, J.M.; Morris, J.S.; Lee, E.J.; Desgagné-Penix, I.; Bross, C.D.; Chang, L.; Chen, X.; Farrow, S.C.; Zhang, Y.; Soh, J.; et al. Transcriptome Analysis of 20 Taxonomically Related Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid-Producing Plants. BMC Plant Biol 2015, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lee, E.-J.; Chang, L.; Facchini, P. Genes Encoding Norcoclaurine Synthase Occur as Tandem Fusions in the Papaveraceae. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 39256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.-L.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Ma, L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, B. Transcriptomic Analysis of Eruca Vesicaria Subs. Sativa Lines with Contrasting Tolerance to Polyethylene Glycol-Simulated Drought Stress. BMC Plant Biol 2019, 19, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Zhong, X.; Gao, Y.; Xu, H.; Hu, H.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, X.; et al. The Regulatory Metabolic Networks of the Brassica Campestris L. Hairy Roots in Response to Cadmium Stress Revealed from Proteome Studies Combined with a Transcriptome Analysis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 263, 115214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H. -f.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, J. -s.; Li, J. -c.; Sun, Q. -m. Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analysis of Pollen Germination Response to Low-Temperature in Pitaya (Hylocereus Polyrhizus). Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.L.; Li, Q.; Yeaman, S.; Facchini, P.J. Elucidation of the Mescaline Biosynthetic Pathway in Peyote (Lophophora Williamsii). The Plant Journal 2023, 116, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhen, W.; Long, D.; Ding, L.; Gong, A.; Xiao, C.; Jiang, W.; Liu, X.; Zhou, T.; Huang, L. De Novo Sequencing and Assembly Analysis of the Pseudostellaria Heterophylla Transcriptome. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0164235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Xu, L.; Luo, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, G.; Gao, H.; Fang, F.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Mechanisms for the Different Drought Tolerance of Sweet Potatoes. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1136709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Sun, Z.; Lai, Z.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Tao, J.; Tang, X. Determination of the MiRNAs Related to Bean Pyralid Larvae Resistance in Soybean Using Small RNA and Transcriptome Sequencing. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacon, D.S.; Torres, T.; da Silva, I.; de Araújo TF; Roque, A.; Pinheiro, F.; Selegato, D.; Pilon, A.; Reginaldo, F.; da Costa, C.; et al. Erythrina Velutina Willd. Alkaloids: Piecing Biosynthesis Together from Transcriptome Analysis and Metabolite Profiling of Seeds and Leaves. J Adv Res 2021, 34, 123–136. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Bao, A.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Metabolome and Transcriptome Integration Explored the Mechanism of Browning in Glycyrrhiza Uralensis Fisch Cells. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Ji, T.; Yuan, L.; Kai, G. Integrated Analysis of the Transcriptome, Metabolome and Analgesic Effect Provide Insight into Potential Applications of Different Parts of Lindera Aggregata. Food Research International 2020, 138, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhao, R.; Wang, F.; Dong, R.; Wang, X. Transcriptome and Metabolome Integrated Analysis Reveals the Mechanism of Cinnamomum Bodinieri Root Response to Alkali Stress. Plant Mol Biol Report 2023, 41, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, D.; Jiang, Z.; Qu, C.; Yan, H.; Wu, Q. Metabolite Profiling and Transcriptomic Analyses Demonstrate the Effects of Biocontrol Agents on Alkaloid Accumulation in Fritillaria Thunbergii. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chang, X.; Shi, Z.; Fang, X.; Chen, F.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Characterization of Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Methyltransferases in Liriodendron Chinense Provides Insights into the Phylogenic Basis of Angiosperm Alkaloid Diversity. The Plant Journal 2022, 112, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, A.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M. Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiling of the Medicinal Plant Veratrum Mengtzeanum Reveal Key Components of the Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Front Genet 2023, 14, 1023433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Candidate Genes Involved in Isoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Stephania Tetrandra. Planta Med 2020, 86, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, Q.; Hu, J.; Kai, G.; Feng, Y. Transcriptome Analysis of Stephania Tetrandra and Characterization of Norcoclaurine-6-O-Methyltransferase Involved in Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 874583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wei, Y.; Huang, S.; Lu, S.; Su, H.; Ma, L.; Huang, W. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Provide Insights into Regulation Mechanisms during Bulbous Stem Development in the Chinese Medicinal Herb Plant, Stephania Kwangsiensis. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Feng, J.; Liu, Y. Digital Gene Expression Analysis Provides Insight into the Transcript Profile of the Genes Involved in Aporphine Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Lotus (Nelumbo Nucifera). Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Song, H.; Deng, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Xin, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Transcriptome-Wide Characterization of Alkaloids and Chlorophyll Biosynthesis in Lotus Plumule. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, L.-C.; Cushman, S.A. Transcriptomic Responses and Physiological Changes to Cold Stress among Natural Populations Provide Insights into Local Adaptation of Weeping Forsythia. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 165, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Wei, M.; Fan, H.; Song, C.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Jin, Q. Transcriptomic Analysis of Genes Related to Alkaloid Biosynthesis and the Regulation Mechanism under Precursor and Methyl Jasmonate Treatment in Dendrobium Officinale. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagné-Penix, I.; Khan, M.F.; Schriemer, D.C.; Cram, D.; Nowak, J.; Facchini, P.J. Integration of Deep Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses Reveals the Components of Alkaloid Metabolism in Opium Poppy Cell Cultures. BMC Plant Biol 2010, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyal, A.; Tripathi, H.; Yadav, D.K.; Khan, F.; Gupta, V.; Shukla, R.K.; Darokar, M.P. Functional Annotation of Expressed Sequence Tags of Papaver Somniferum. Plant Omics 2012, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Huang, P.; Zhu, P.; Chen, J.; Shi, M.; Guo, F.; et al. Integration of Transcriptome, Proteome and Metabolism Data Reveals the Alkaloids Biosynthesis in Macleaya Cordata and Macleaya Microcarpa. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Lakhwani, D.; Gupta, P.; Mishra, B.K.; Shukla, S.; Asif, M.H.; Trivedi, P.K. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Using High Papaverine Mutant of Papaver Somniferum Reveals Pathway and Uncharacterized Steps of Papaverine Biosynthesis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, D.; Wang, P.; Jia, C.; Sun, P.; Qi, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, X. Identification and Developmental Expression Profiling of Putative Alkaloid Biosynthetic Genes in Corydalis Yanhusuo Bulbs. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, P.; Pathak, S.; Lakhwani, D.; Gupta, P.; Asif, M.H.; Trivedi, P.K. Comparative Analysis of Transcription Factor Gene Families from Papaver Somniferum: Identification of Regulatory Factors Involved in Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Protoplasma 2016, 253, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.M.; Song, W.L.; Cong, K.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, G.H.; Yang, J.L.; Yang, S.C.; et al. Identification of Candidate Genes Involved in Isoquinoline Alkaloids Biosynthesis in Dactylicapnos Scandens by Transcriptome Analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Ma, Y.; Qing, Z.; Tang, Q.; Cao, H.; Cheng, P.; Zheng, Y.; Yuan, Z.; et al. The Genome of Medicinal Plant Macleaya Cordata Provides New Insights into Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Metabolism. Mol Plant 2017, 10, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jung, M.; Ha, I.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, S.-G.; Shin, Y.; Subramaniyam, S.; Oh, J. Transcriptional Profiles of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis Genes and Cytochromes in the Leaves of Four Papaver Species. Data (Basel) 2018, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Shin, Y.; Ha, I.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, S.-G.; Kang, B.-C.; Kyeong, D.; Kim, D. Transcriptome Profiling of Two Ornamental and Medicinal Papaver Herbs. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Winzer, T.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Ning, Z.; He, Z.; Teodor, R.; Lu, Y.; Bowser, T.A.; Graham, I.A.; et al. The Opium Poppy Genome and Morphinan Production. Science 2018, 362, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmazaheri, H.; Soorni, A.; Baghban Kohnerouz, B.; Khosravi Dehaghi, N.; Kalantar, E.; Omidi, M.; Naghavi, M.R. Comparative Analysis of the Root and Leaf Transcriptomes in Chelidonium Majus L. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Luo, J.; Chen, F.; Gong, Y.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Su, Y.; Kong, L. Transcriptomic Profiles of 33 Opium Poppy Samples in Different Tissues, Growth Phases, and Cultivars. Sci Data 2019, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Nishida, S.; Shitan, N.; Sato, F. Genome-Wide Identification of AP2/ERF Transcription Factor-Encoding Genes in California Poppy (Eschscholzia Californica) and Their Expression Profiles in Response to Methyl Jasmonate. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Lin, H.; Tang, Y.; Huang, L.; Xu, J.; Nian, S.; Zhao, Y. Integration of Full-Length Transcriptomics and Targeted Metabolomics to Identify Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthetic Genes in Corydalis Yanhusuo. Hortic Res 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Wang, B.; Ye, J.; Hu, X.; Fu, L.; Li, K.; Ni, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Shi, L.; et al. Genome and Transcriptome of Papaver Somniferum Chinese Landrace CHM Indicates That Massive Genome Expansion Contributes to High Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Hortic Res 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, T.; Li, Y., W. T.; Harvey, D.; Meade, F.; Caridi, A.; Leech, A.; Larson, T.R.; Ning, Z.; Chang, J.; Van de Peer, Y.; et al. A Functionally Conserved STORR Gene Fusion in Papaver Species That Diverged 16.8 Million Years Ago. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Manoharan, D.; Li, J.; Britton, M.; Parida, A. Drought and Salt Stress in Chrysopogon Zizanioides Leads to Common and Specific Transcriptomic Responses and May Affect Essential Oil Composition and Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Metabolism. Curr Plant Biol 2017, 11–12, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Hu, G. Integrated Analysis of the Transcriptome and Metabolome Revealed Candidate Genes Involved in GA3-Induced Dormancy Release in Leymus Chinensis Seeds. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, T.; Malhotra, N.; Chanumolu, S.K.; Chauhan, R.S. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Transcriptomes Reveal Association of Multiple Genes and Pathways Contributing to Secondary Metabolites Accumulation in Tuberous Roots of Aconitum Heterophyllum Wall. Planta 2015, 242, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.M.; Liang, Y.L.; Cong, K.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Q.M.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Yang, J.L.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Genes Involved in Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Coptis Species. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 328684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xu, S.; Mengyan, W.; Yongbin, T.; Xu, C.; Hailey, H.; Kai, T.; Lan, M.; Ji, C.; Weiping, Z.; et al. Systematic Estimation of Potential Risk Caused by the Replacement of Aconite’s Cultivar. Pharmacogn Mag 2019, 15, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Huang, L.; Qi, L.; Ma, Y.; Yan, Z. Full-Length Transcriptome Analysis of Coptis Deltoidea and Identification of Putative Genes Involved in Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Biosynthesis Based on Combined Sequencing Platforms. Plant Mol Biol 2020, 102, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, D.C.; Li, P.; Xiao, P.G.; He, C.N. Dissection of Full-Length Transcriptome and Metabolome of Dichocarpum (Ranunculaceae): Implications in Evolution of Specialized Metabolism of Ranunculales Medicinal Plants. PeerJ 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.M.; Tan, J.P.; Cheng, S.Y.; Chen, Z.X.; Ye, J.B.; Zheng, J.R.; Xu, F.; Zhang, W.W.; Liao, Y.L.; Yang, X.Y. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Provides Novel Insights into the Molecular Mechanism of Berberine Biosynthesis in Coptis Chinensis. Sci Hortic 2022, 291, 110585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; You, J.; Wang, J.; Tang, T.; Guo, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Mu, S.; Wang, Q.; Niu, X.; et al. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Potential Mechanism of Altering Viability, Yield, and Isoquinoline Alkaloids in Coptis Chinensis through Cunninghamia Lanceolata Understory Cultivation. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2024, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, B.; Sahito, Z.A.; Chen, S.; Liang, Z. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Cadmium Exposure Enhanced the Isoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis and Disease Resistance in Coptis Chinensis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2024, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Ke, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, T.; Xu, B.; Qi, L.; Yan, Z.; Ma, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Three Coptis Species (C. Chinensis, C. Deltoidea and C. Omeiensis): The Important Medicinal Plants in China. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1166420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Tan, G.; Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, S.; Xu, P.; Sun, M.; et al. A Genome Assembly of Decaploid Houttuynia Cordata Provides Insights into the Evolution of Houttuynia and the Biosynthesis of Alkaloids. Hortic Res 2024, 11, uhae203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, P.; Yao, X.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lin, P.; Wang, K. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Reveals Key Metabolites Involved in Camellia Oleifera Defense against Anthracnose. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Li, H.; Pan, J.; Zhou, B.; He, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, D.; He, W.; Chen, L. Salicylic Acid Modulates Secondary Metabolism and Enhanced Colchicine Accumulation in Long Yellow Daylily (Hemerocallis Citrina). AoB Plants 2024, 16, plae029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, Z.; Sun, J.; Cui, X.; Liu, Y. Research Progress and Future Development Trends in Medicinal Plant Transcriptomics. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 691838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Zhu, T.; Hu, X.; Hou, C.; He, J.; Liu, X. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis of Isoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis of Coptis Chinensis in Different Years. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezawa, N.; Tanaka, M.; Nagayoshi, M.; Shinkyo, R.; Sakaki, T.; Inouye, K.; Sato, F. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of CYP719, a Methylenedioxy Bridge-Forming Enzyme That Belongs to a Novel P450 Family, from Cultured Coptis Japonica Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 38557–38565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikezawa, N.; Iwasa, K.; Sato, F. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of CYP80G2, a Cytochrome P450 That Catalyzes an Intramolecular C-C Phenol Coupling of (S)-Reticuline in Magnoflorine Biosynthesis, from Cultured Coptis Japonica Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 8810–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Park, N. Il; Park, Y.; Park, K.C.; Kim, E.S.; Son, Y.K.; Choi, B.S.; Kim, N.S.; Choi, I.Y. O- and N-Methyltransferases in Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Producing Plants. Genes Genomics 2024, 46, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, P.J.; Morris, J.S. Molecular Origins of Functional Diversity in Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Methyltransferases. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveals That Exogenous Methyl Jasmonate Regulates Galanthamine Biosynthesis in Lycoris Longituba Seedlings. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 713795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nett, R.S.; Lau, W.; Sattely, E.S. Discovery and Engineering of Colchicine Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Nature 2020, 584, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ounaroon, A.; Decker, G.; Schmidt, J.; Lottspeich, F.; Kutchan, T.M. (R,S)-Reticuline 7-O-Methyltransferase and (R,S)-Norcoclaurine 6-O-Methyltransferase of Papaver Somniferum – CDNA Cloning and Characterization of Methyl Transfer Enzymes of Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Opium Poppy. The Plant Journal 2003, 36, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Kong, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Pan, H. Development of an Artificial Biosynthetic Pathway for Biosynthesis of (S)-Reticuline Based on HpaBC in Engineered Escherichia Coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 2021, 118, 4635–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Liang, L.; He, J.; Peng, F.; Xia, B. De Novo Sequence Assembly and Characterization of Lycoris Aurea Transcriptome Using GS FLX Titanium Platform of 454 Pyrosequencing. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadegan, V.; Koirala, M.; Sobhanverdi, S.; Merindol, N.; Majhi, B.B.; Gélinas, S.E.; Timokhin, V.I.; Ralph, J.; Dastmalchi, M.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Characterization of Cinnamate 4-Hydroxylase (CYP73A) and p-Coumaroyl 3′-Hydroxylase (CYP98A) from Leucojum Aestivum, a Source of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 210, 108612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, M.; Cristine Goncalves dos Santos, K.; Gélinas, S.E.; Ricard, S.; Karimzadegan, V.; Lamichhane, B.; Sameera Liyanage, N.; Merindol, N.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Auxin and Light-Mediated Regulation of Growth, Morphogenesis, and Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Crinum x Powellii “Album” Callus. Phytochemistry 2023, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousignant, L.; Diaz-Garza, A.M.; Majhi, B.B.; Gélinas, S.-E.; Singh, A.; Desgagne-Penix, I. Transcriptome Analysis of Leucojum Aestivum and Identification of Genes Involved in Norbelladine Biosynthesis. Planta 2022, 255, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, N.; Xia, B.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, R. Identification and Differential Regulation of MicroRNAs in Response to Methyl Jasmonate Treatment in Lycoris Aurea by Deep Sequencing. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, B.; Wang, R. Selection and Validation of Appropriate Reference Genes for Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of Gene Expression in Lycoris Aurea. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Wang, N.; Xia, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, R. Transcriptome Analysis of Secondary Metabolism Pathway, Transcription Factors, and Transporters in Response to Methyl Jasmonate in Lycoris Aurea. Front Plant Sci 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wu, M.; Sun, B.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, M.; Xue, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, R. Identification of Transcription Factor Genes Responsive to MeJA and Characterization of a LaMYC2 Transcription Factor Positively Regulates Lycorine Biosynthesis in Lycoris Aurea. J Plant Physiol 2024, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, G.; Shu, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, Z. Transcriptome Analysis of Lycoris Chinensis Bulbs Reveals Flowering in the Age-Mediated Pathway. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y. Transcriptome Analysis of Different Tissues Reveals Key Genes Associated With Galanthamine Biosynthesis in Lycoris Longituba. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 519752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Yeo, H.J.; Park, Y.E.; Baek, S.A.; Kim, J.K.; Park, S.U. Transcriptome Analysis and Metabolic Profiling of Lycoris Radiata. Biology (Basel) 2019, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchandani, T.; de Villers, J.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Developmental Regulation of the Expression of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Biosynthetic Genes in Narcissus Papyraceus. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiling of Narcissus Pseudonarcissus “King Alfred” Reveal Components of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Metabolism. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdausi, A.; Chang, X.; Jones, M. Transcriptomic Analysis for Differential Expression of Genes Involved in Secondary Metabolite Production in Narcissus Pseudonarcissus Field Derived Bulb and in Vitro Callus. Ind Crops Prod 2021, 168, 113615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, M.B.; Holland, C.K.; Jez, J.M.; Kutchan, T.M. Identification of a Noroxomaritidine Reductase with Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Biosynthesis Related Activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 16740–16752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, H.M.; Wang, R.; Li, X.D.; Jiang, Y.M.,F.P. ; Xia, B. Alkaloid Accumulation in Different Parts and Ages of Lycoris Chinensis. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2010, 65, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Han, X.; Xu, S.; Xia, B.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, R. Cloning and Characterization of a Tyrosine Decarboxylase Involved in the Biosynthesis of Galanthamine in Lycoris Aurea. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef D. T., A.; Shaala, L.A.; Altyar, A.E. Cytotoxic Phenylpropanoid Derivatives and Alkaloids from the Flowers of Pancratium Maritimum L. Plants 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, D.T.A. Cytotoxic Phenolics from the Flowers of Hippeastrum Vittatum. Bulletin of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Assiut 2005, 28, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takos, A.M.; Rook, F. Towards a Molecular Understanding of the Biosynthesis of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids in Support of Their Expanding Medical Use. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 11713–11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Luo, T.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Zhou, D.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Pandey, A.; Luo, Z. Transcriptomics-Based Identification and Characterization of 11 CYP450 Genes of Panax Ginseng Responsive to MeJA. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2018, 50, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, WF.; Xiao, H.; Zhong, JJ. Biosynthesis of a Novel Ganoderic Acid by Expressing CYP Genes from Ganoderma Lucidum in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 106, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhan, X.; Wang, W.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Deng, J.; Yang, H. Natural Aporphine Alkaloids: A Comprehensive Review of Phytochemistry, Pharmacokinetics, Anticancer Activities, and Clinical Application. J Adv Res 2024, 63, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, L.E.; Narayan, A.R.H. Broadening the Scope of Biocatalytic C–C Bond Formation. Nat Rev Chem 2020, 4, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Qiao, C.; Pang, J.; Zhang, G.; Luo, Y. The Versatile O-Methyltransferase LrOMT Catalyzes Multiple O-Methylation Reactions in Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids Biosynthesis. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 141, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, M.T.; Ul Hasnain, M.J.; Abbas, S.H.; Moustafa, M.F.; Aslam, N.; Shah, S.S.M. A Comprehensive Review of Performance of Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms. Biomed Res Int 2022, e3457806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, S.; Meola, M.; Egli, A. Combination of Whole Genome Sequencing and Metagenomics for Microbiological Diagnostics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23, Page 9834 2022, 23, 9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Buckler, E.S.; Stitzer, M.C. New Whole-Genome Alignment Tools Are Needed for Tapping into Plant Diversity. Trends Plant Sci 2024, 29, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shang, L.; Zhu, Q.H.; Fan, L.; Guo, L. Twenty Years of Plant Genome Sequencing: Achievements and Challenges. Trends Plant Sci 2022, 27, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X. Recent Advances in Assembly of Complex Plant Genomes. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2023, 21, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schinkel, C.C.F.; Kirchheimer, B.; Dullinger, S.; Geelen, D.; De Storme, N.; Hörandl, E. Pathways to Polyploidy: Indications of a Female Triploid Bridge in the Alpine Species Ranunculus Kuepferi (Ranunculaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 2017, 303, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerow, A.W.; Gardner, E.M.; Nakamura, K. Phylogenomics of the Andean Tetraploid Clade of the American Amaryllidaceae (Subfamily Amaryllidoideae): Unlocking a Polyploid Generic Radiation Abetted by Continental Geodynamics. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 582422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, E.; Narcross, L.; Ekins, A.; Falgueyret, J.-P.; Martin, VJJ. Synthesis of Morphinan Alkaloids in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0124459. [CrossRef]

- Thodey K., G.S. ; Smolke, C.D. A Microbial Biomanufacturing Platform for Natural and Semisynthetic Opioids. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narcross, L.; Fossati, E.; Bourgeois, L.; Dueber, J.E.; Martin, V.J. Microbial Factories for the Production of Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids. Trends Biotechnol 2016, 34, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; et al. Bioinspired Scalable Total Synthesis of Opioids. CCL Chemistry 2021, 13, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. ; others High-Efficiency Biocatalytic Conversion of Thebaine to Codeine. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 9339–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aspect | Isoquinoline Alkaloids (IsAs) | Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids (AmAs) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Metabolic Pathways | Norcoclaurine → Reticuline → Morphine | Norbelladine → 4OMET → Galanthamine/Lycorine |

| Main Precursors | L-tyrosine, L-DOPA | L-tyrosine, L-phenylalanine |

| Key Enzymes | Methyltransferases, oxidoreductases (CYP719B, STORR) | Norbelladine synthase (NBS), CYP96T1, N4OMT |

| Phenolic Couplings | Intramolecular: Ortho-Ortho, Para-Ortho | Intramolecular: Para-Para, Para-Ortho, Ortho-Para |

| Taxonomic Distribution | 28 families in 17 orders (mainly Ranunculales) | Mainly in Amaryllidaceae, with exceptions in Asparagaceae |

| Progress in Elucidation | Pathway almost fully characterized | Pathway partially elucidated with major gaps (e.g., 3,4-DHBA) |

| Biotechnological Applications | Morphine production in microorganisms | Galanthamine production for Alzheimer’s treatment |

| Current Limitations | Structural complexity of final metabolites | Lack of integrated genomic and transcriptomic data |

| Family | Sequencing year | Sequencing country | Sequencing platforms |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | 2020 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [50] |

| Araceae | 2021, 2022 and 2024 | China | Illumina Nova seq 6000 and Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [51,52,53] |

| Aristolochiaceae | 2021 and 2022 | China | PacBio Iso-Seq, Illumina HiSeq2500 & Oxford Nanopore. | [54,55] |

| Asteraceae | 2021 | China | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | [56] |

| Berberidaceae | 2012, 2014, 2015 and 2016 | Canada and U.S.A. | Illumina and 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing | [57,58,59,60] |

| Brassicaceae | 2019 and 2023 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [61,62] |

| Cactaceae | 2022 and 2023 | China and Canada | Illumina HiSeq X Ten and Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | [63,64] |

| Caryophyllaceae | 2016 | China | Illumina HiSeq 4000 | [65] |

| Convolvulaceae | 2023 | China | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | [66] |

| Fabaceae | 2019, 2021 and 2024 | China and Brazil | Illumina HiSeq 2000 and Illumina NextSeq 500 | [67,68,69] |

| Lauraceae | 2020 and 2023 | China | bgiSeq-500 and Illumina | [70,71] |

| Liliaceae | 2023 | China | Illumina Novaseq6000 | [72] |

| Magnoliaceae | 2022 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [73] |

| Melanthiaceae | 2023 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [74] |

| Menispermaceae | 2012, 2015, 2016, 2020, 2022 and 2024 | Canada and China | Illumina, 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing, Illumina HiSeq X Ten, Illumina HiSeq-2500 | [57,59,60,75,76,77] |

| Nelumbonaceae | 2017 and 2022 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

[78,79] |

| Oleaceae | 2021 | China | Illumina HiSeq X Ten | [80] |

| Orchidaceae | 2022 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [81] |

| Papaveraceae | 2010, 2012 (3), 2013 (2), 2015 (2), 2016 (3), 2017 (2), 2018 (3), 2019 (2), 2020, 2021 (2) and 2022. | Canada, China, Iran, Japan, Korea, Turkey and U.K. | 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing, Illumina HiSeq 2000, Illumina HiSeq 2500, Illumina HiSeq 3000, Illumina HiSeq 4000, Illumina HiSeq X Ten and PacBio Iso-Seq | [82,57,83,84,85,59,60,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Poaceae | 2017 and 2021 | India and China | Illumina HiSeq 4000 | [99,100] |

| Ranunculaceae | 2012, 2015 (2), 2016, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024 | Canada, China | Illumina, 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing, Illumina HiSeq 2000, Illumina HiSeq 2500, Illumina HiSeq X Ten, PacBio Iso-Seq, Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | [57,59,60,101,10][] |

| Saururaceae | 2024 | China | Illumina/MGI-SEQ 2000 | [110] |

| Theaceae | 2022 | China | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [111] |

| Xanthorrhoeaceae | 2024 | China | Illumina HiSeq xten/NovaSeq6000 | [112] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).