Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Procedures

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Extraction and Isolation

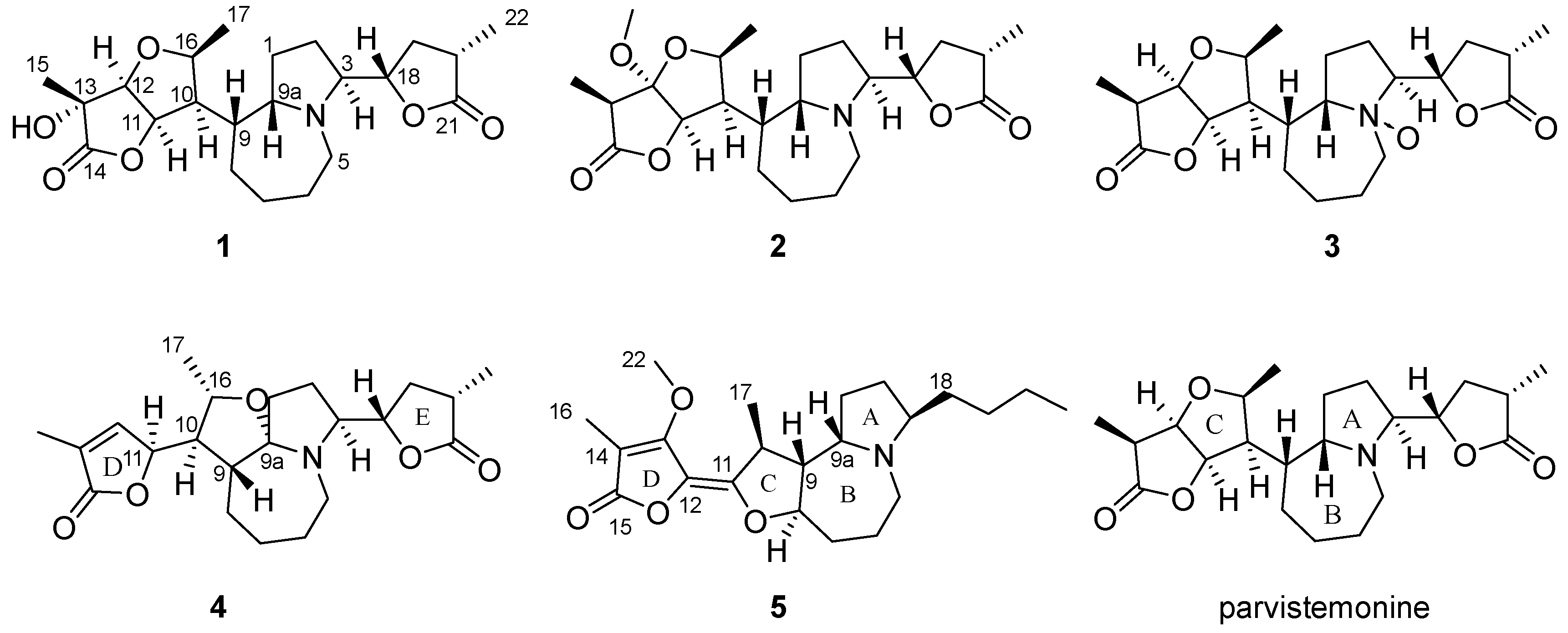

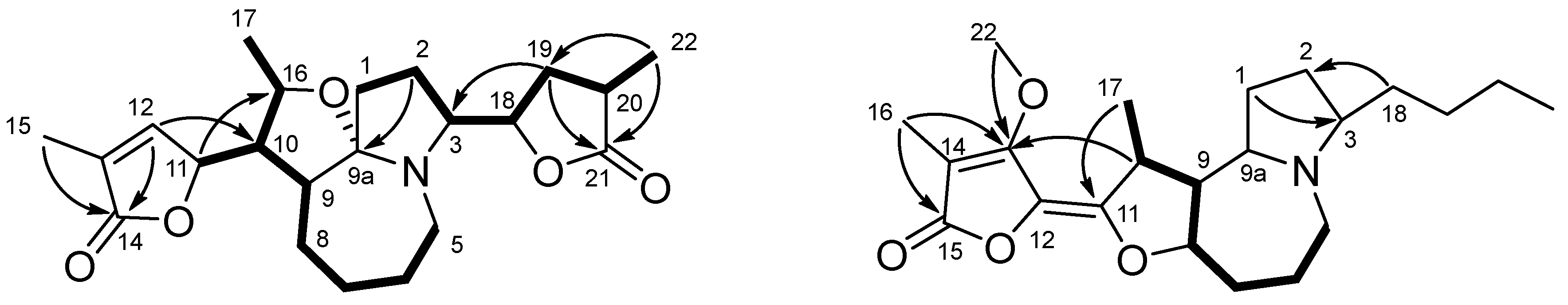

2.3.1. 13α-Hydroxyparvistemonine (1)

2.3.2. 12α-Methloxylparvistemonine (2)

2.3.3. Parvistemonine-N-Oxide (3)

2.3.4. Parvistemoninine (4)

2.3.5. Parvistemofoline (5)

3. Results

| No. | 1 | 2 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1.42, m 1.64, m |

1.40, m 1.64, m |

1.67, m 1.90, m |

| 2 |

1.59, m 1.75, m |

1.59, m 1.75, m |

1.42, m 2.05, m |

| 3 | 3.45, m | 3.40, m | 3.16, m |

| 5 |

2.87, dd (15.7, 11.9) 3.40, m |

2.85, d (11.7) 3.30, dd (11.7, 7.9) |

2.99, dd (14.4, 11.4) 2.74, d (14.4) |

| 6 |

1.44, m 1.72, m |

1.42, m 1.70, m |

1.59, m 1.65, m |

| 7 |

1.42, m; 1.82, m |

1.38, m 1.77, m |

1.42, m; 1.61, m |

| 8 |

1.46, m; 1.92, m |

1.45, m 1.91, m |

1.60, m 1.71, m |

| 9 | 2.18, m | 2.15, m | 2.38, m |

| 9a | 3.45, m | 3.43, m | |

| 10 | 2.15, m | 2.30, m | 2.01, m |

| 11 | 5.14, d (3.8) | 4.61, d (4.3) | 4.84, dd (3.4, 1.7) |

| 12 | 4.25, d (3.8) | 7.02, d (1.7) | |

| 13 | 2.89, m | ||

| 15 | 1.50, s, 3H | 1.34, d (7.2) | 1.92, s |

| 16 | 4.30, m | 4.48, m | 3.55, m |

| 17 | 1.15, d (6.7), 3H | 1.20, d (6.6) | 1.28, d (5.9) |

| 18 | 4.20, m | 4.17, ddd (10.8, 7.1, 5.3) | 4.22, m |

| 19 |

1.55, m 2.37, m |

1.55, m 2.35, m |

2.36, m 1.49, m |

| 20 | 2.61, m | 2.59, m | 2.62, m |

| 22 | 1.25, d (7.1), 3H | 1.25, d (7.0), 3H | 1.24, d (7.0), 3H |

| 23-OMe | 3.35, s, 3H |

| No. | 1 | 2 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27.0 t | 27.1 t | 38.6 t |

| 2 | 26.8 t | 26.9 t | 23.7 t |

| 3 | 63.7 d | 63.7 d | 67.0 d |

| 5 | 46.5 t | 46.6 t | 46.0 t |

| 6 | 24.5 t | 24.8 t | 23.1 t |

| 7 | 28.6 t | 28.7 t | 31.2 t |

| 8 | 26.7 t | 26.9 t | 27.0 t |

| 9 | 39.1 d | 39.0 d | 46.5 d |

| 9a | 62.8 d | 62.9 d | 105.1 s |

| 10 | 49.4 d | 47.4 d | 50.3 d |

| 11 | 84.0 d | 86.4 d | 80.9 d |

| 12 | 84.4 d | 110.3 s | 147.3 d |

| 13 | 76.1 s | 44.7 d | 130.6 s |

| 14 | 177.6 s | 176.3 s | 173.8 s |

| 15 | 18.6 q | 10.0 q | 10.8 q |

| 16 | 77.9 d | 79.4 d | 71.3 d |

| 17 | 19.3 q | 19.4 q | 20.2 q |

| 18 | 83.3 d | 83.4 d | 82.2 d |

| 19 | 34.2 t | 34.2 t | 33.7 t |

| 20 | 34.9 d | 35.0 d | 35.4 d |

| 21 | 179.8 s | 179.7 s | 179.9 s |

| 22 | 14.9 q | 15.0 q | 15.2 q |

| 23-OMe | 51.2 q |

| No. | δH | δC |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.50, m 1.93, m |

27.3 t |

| 2 | 1.48, m 2.01, m |

30.9 t |

| 3 | 3.03, m | 61.1 d |

| 5 | 3.21, dd (11.7, 4.1) 2.98, dd (11.7, 7.9) |

44.8 t |

| 6 | 1.52, m 1.68, m |

18.9 t |

| 7 | 1.51, m 2.34, m |

33.7 t |

| 8 | 4.13, m | 83.8 d |

| 9 | 2.22, m | 56.1 d |

| 9a | 3.83, m | 58.3 d |

| 10 | 2.92, m | 39.4 d |

| 11 | 149.1 s | |

| 12 | 124.6 s | |

| 13 | 163.3 s | |

| 14 | 97.1 s | |

| 15 | 170.2 s | |

| 16 | 2.04, s, 3H | 9.2 q |

| 17 | 1.33, d, 3H | 20.7 q |

| 18 | 1.22, m 1.64, m |

32.4 t |

| 19 | 1.25, m, 2H | 28.4 t |

| 20 | 1.30, m, 2H | 23.0 t |

| 21 | 0.88, t (7.0), 3H | 14.1 q |

| 22-OMe | 4.11, s, 3H | 58.9 q |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, R.; Xu, W.; Lu, Q.; Li, P.; Losh, J.; Hina, F.; Li, E.; Qiu, Y. Generation and classification of transcriptomes in two Croomia species and molecular evolution of CYC/TB1 genes in Stemonaceae. Plant Divers. 2018, 40, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.W.; Hon, P.M.; Xu, Y.T.; Chan, Y.M.; Xu, H.X.; Shaw, P.C.; But, P.P.H. Isolation and chemotaxonomic significance of tuberostemospironine-type alkaloids from Stemona tuberosa. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.W.; Hon, P.M.; Xu, Y.T.; Chan, Y.M.; Xu, H.X.; Shaw, P.C.; But, P.P.H. Isolation and chemotaxonomic significance of tuberostemospironine-type alkaloids from. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Shen, Y.; Teng, L.; Yang, L.F.; Cao, K.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, J.L. The traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of Stemona species: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greger, H. Structural classification and biological activities of Stemona alkaloids. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 463–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Thi, C.; Vo-Cong, D.; Giang, L.D.; Dau-Xuan, D. Isolation and bioactivities of Stemona Alkaloid: A review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ge, J.; Yang, J.; Dunn, B.; Chen, G. Genetic diversity of Stemona parviflora: A threatened myrmecochorous medicinal plant in China. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2017, 71, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Z.; Kong, F.D.; Ma, Q.Y.; Guo, Z.K.; Zhou, L.M.; Wang, Q.; Dai, H.F.; Zhao, Y.X. Nematicidal Stemona alkaloids from Stemona parviflora. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2599–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.Q.; He, Z.S.; Yang, Y.P.; Ye, Y. A novel alkaloid from Stemona parviflora. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2003, 14, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.H.; Xu, R.S.; Zhong, Q.X. Chemical studies on Stemona alkaloids. I. Studies on new alkaloids of Stemona parviflora C. H. Wright. Acta Chim. Sin. 1991, 49, 927–931. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.H.; Xu, R.S.; Zhong, Q.X. Chemical studies on Stemona alkaloids. II. Studies on the minor alkaloids of Stemona parviflora Wright C. H. Acta Chim. Sin. 1991, 49, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.H.; Yin, B.P.; Tang, Z.J.; Xu, R.S.; Zhong, Q.X. The structure of parvistemonine. Acta Chim. Sin. 1990, 48, 811–814. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Z.; Gulder, T.A.A.; Reichert, M.; Tang, C.P.; Ke, C.Q.; Ye, Y.; Bringmann, G. Parvistemins A-D, a new type of dimeric phenylethyl benzoquinones from Stemona parviflora Wright. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 4688–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Z.; Kong, F.D.; Chen, G.; Cai, X.H.; Zhou, L.M.; Ma, Q.Y.; Wang, Q.; Mei, W.L.; Dai, H.F.; Zhao, Y.X. A phytochemical investigation of Stemona parviflora roots reveals several compounds with nematocidal activity. Phytochemistry 2019, 159, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilli, R.A.; de Oliveira, M.D.C.F. Recent progress in the chemistry of the Stemona alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000, 17, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilli, R.A.; Rosso, G.B.; de Oliveira, M.D.F. The chemistry of Stemona alkaloids: An update. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1908–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Qin, G.W.; Xu, R.S. Alkaloids of Stemona japonica. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.S.; Lu, Y.J.; Chu, J.H.; Iwashita, T.; Naoki, H.; Naya, Y.; Nakanishi, K. Studies on some new Stemona alkaloids - a diagnostically Useful 1H-NMR line-broadening effect. Tetrahedron 1982, 38, 2667–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Xu, R.S. Studies on new alkaloids of Stemona japonica. Chin. Chem. Lett. 1992, 3, 511–514. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenegger, E.; Brem, B.; Mereiter, K.; Kalchhauser, H.; Kählig, H.; Hofer, O.; Vajrodaya, S.; Greger, H. Insecticidal pyrido[1,2-α]azepine alkaloids and related derivatives from Stemona species. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, H.; Obata, S.; Kakayama, N.; Ohta, K. CONFLEX 8, CONFLEX Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 2017.

- Zanardi, M.M.; Sarotti, A.M. Sensitivity Analysis of DP4+with the Probability Distribution Terms: Development of a Universal and Customizable Method. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 8544–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irie, H.; Masaki, N.; Ohno, K.; Osaki, K.; Taga, T.; Uyeo, S. The crystal structure of a new alkaloid, stemofoline, from Stemona japonica. J. Chem. Soc. D 1970, 0, 1066–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Z.; Zhu, J.Y.; Tang, C.P.; Ke, C.Q.; Lin, G.; Cheng, T.Y.; Rudd, J.A.; Ye, Y. Alkaloids from roots of Stemona sessilifolia and their antitussive activities. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.H.; Ye, Y.; Xu, R.S. Studies on new alkaloids of Stemona mairei. Chin. Chem. Lett. 1991, 2, 369–370. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.; Jin, L.; Deng, Z.; Cai, S.; Guo, S.; Lin, W. New Stemona alkaloids from the roots of Stemona sessilifolia. Chem. Biodiver. 2008, 5, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götz, M.; Strunz, G.M. Tuberostemonine and Related Compounds: The Chemistry of Stemona Alkaloids. In Alkaloids, Wiesner, G., Ed. Butterworths: London, 1975; Vol. 9, pp 143-160.

- Greger, H. Structural relationships, distribution and biological activities of Stemona alkaloids. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).