Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

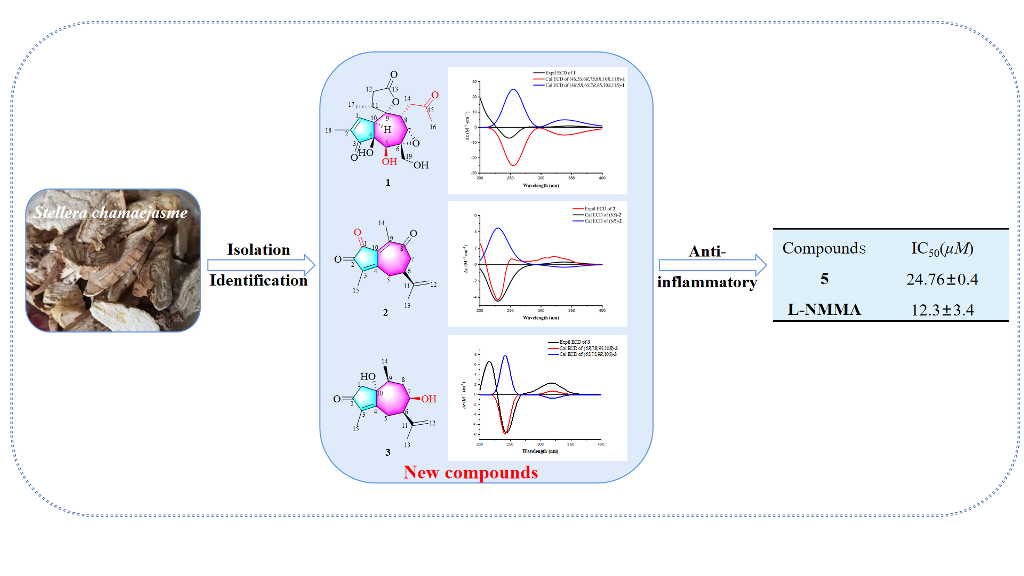

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results and Discussion

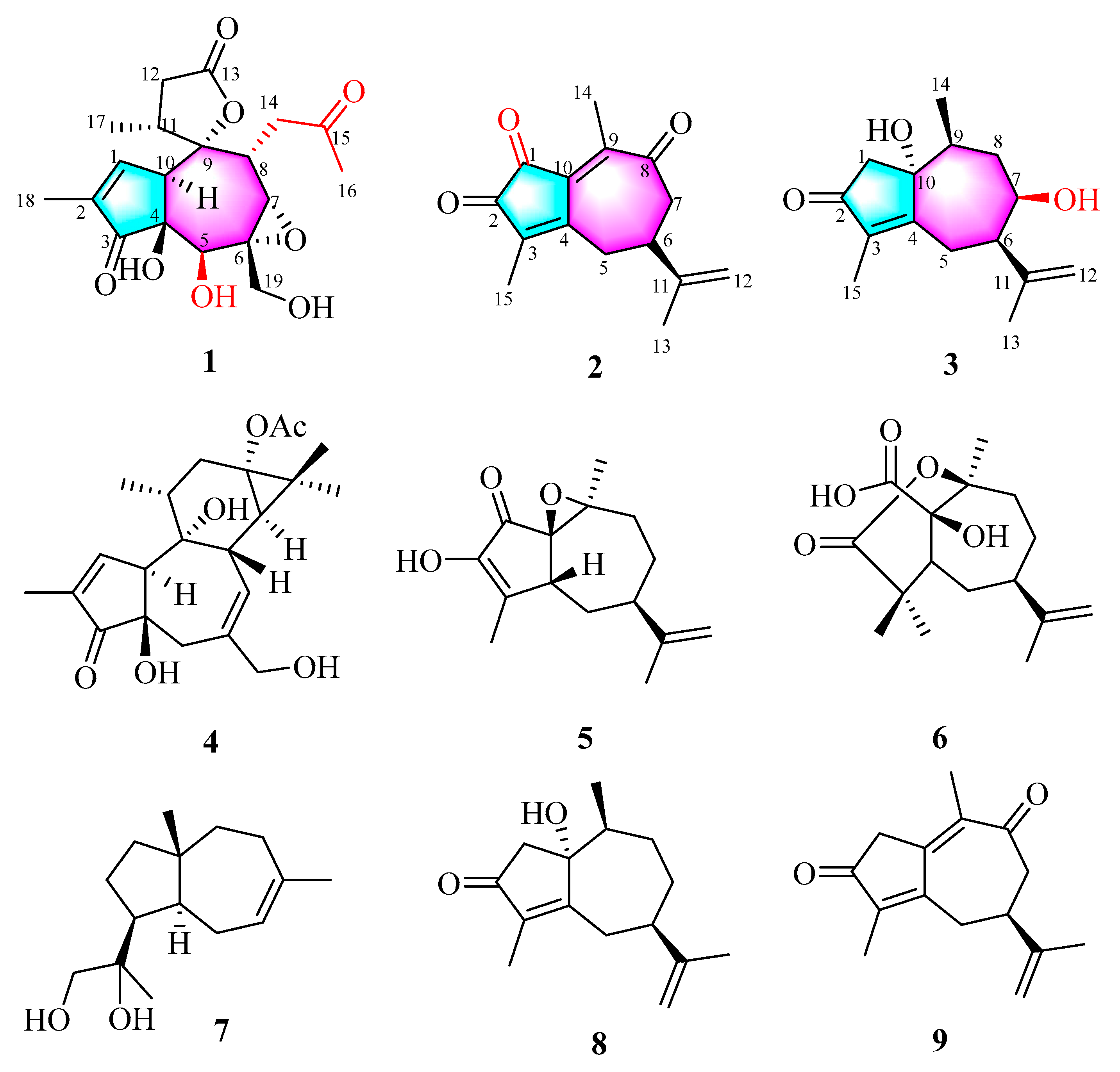

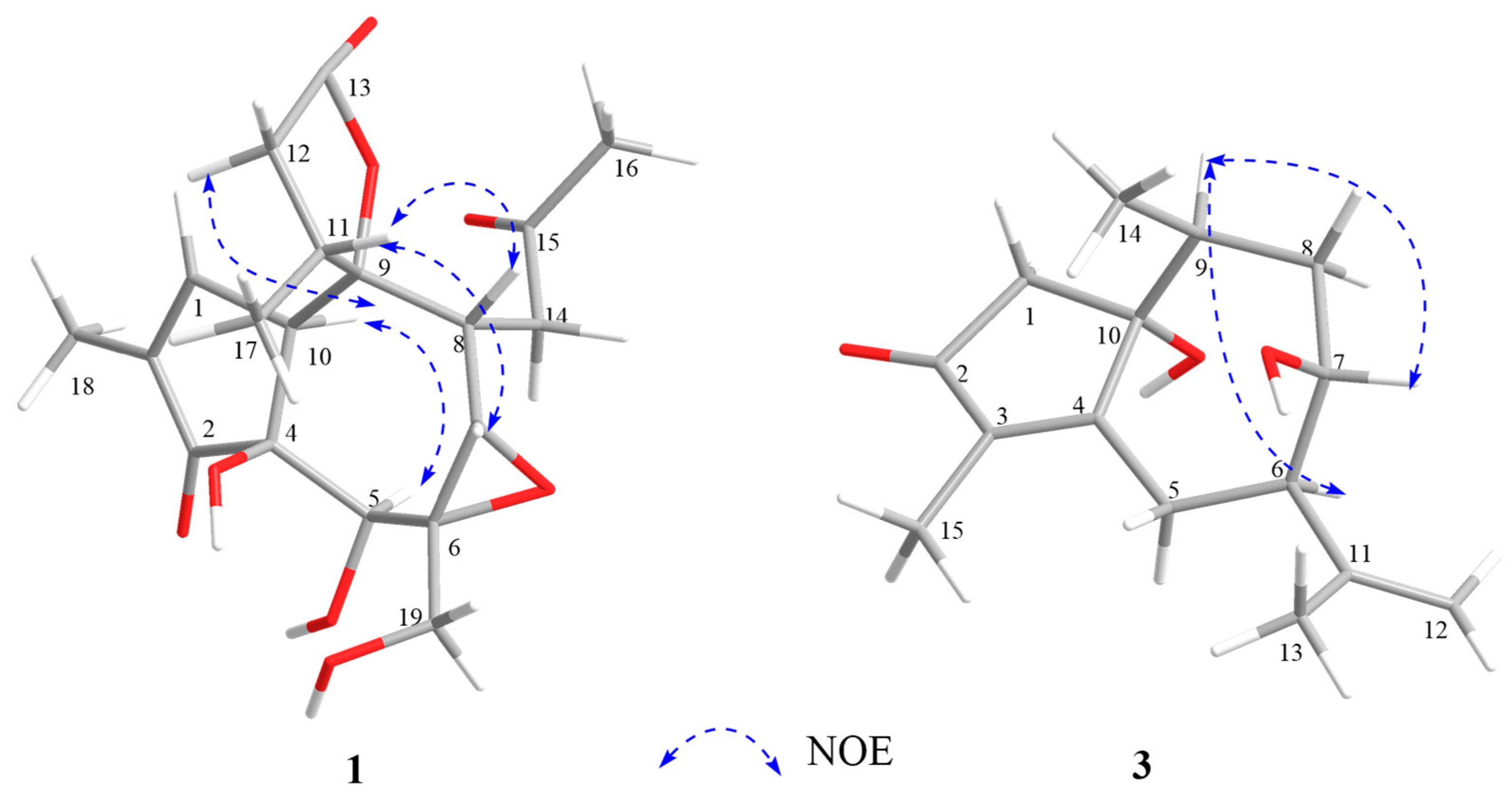

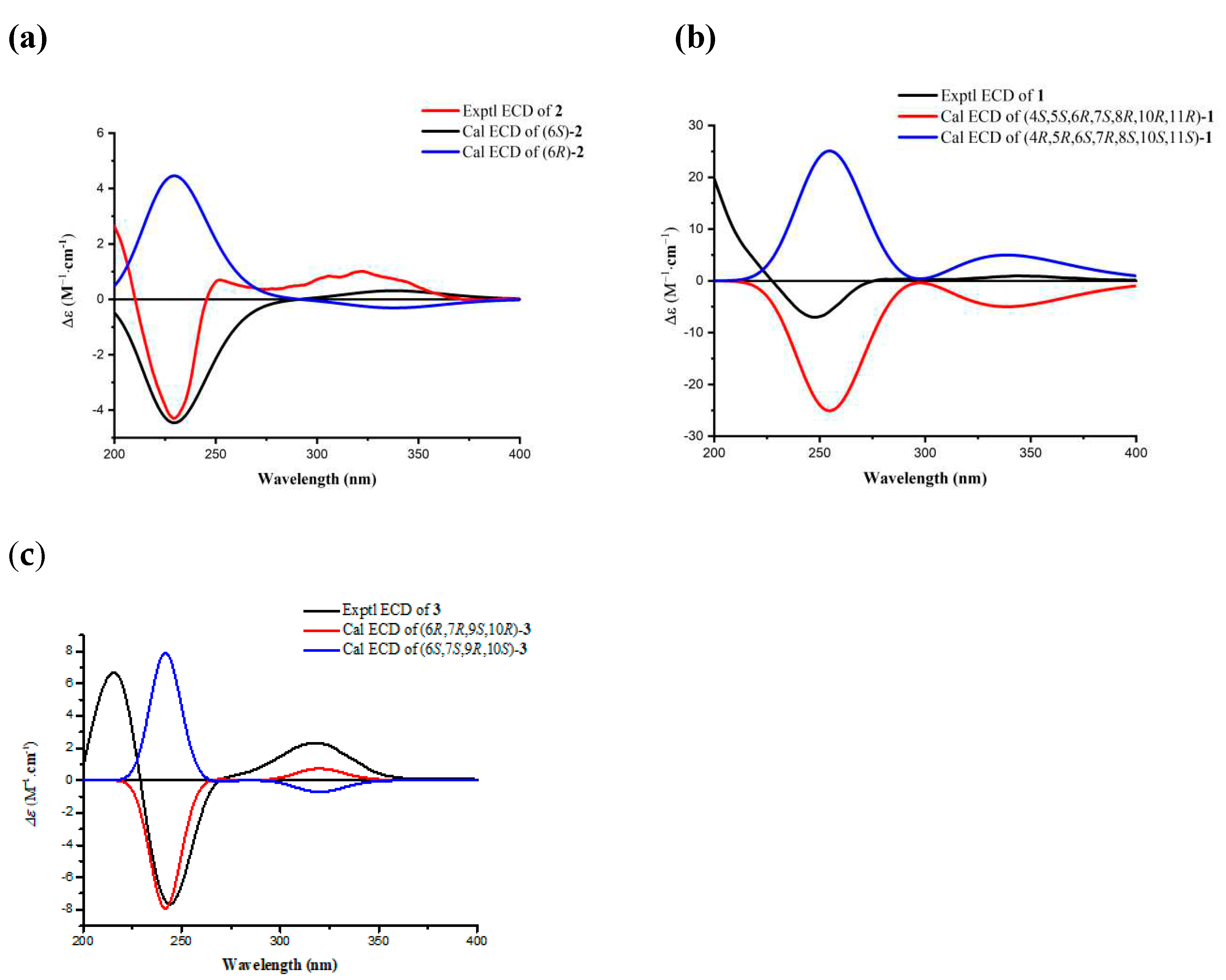

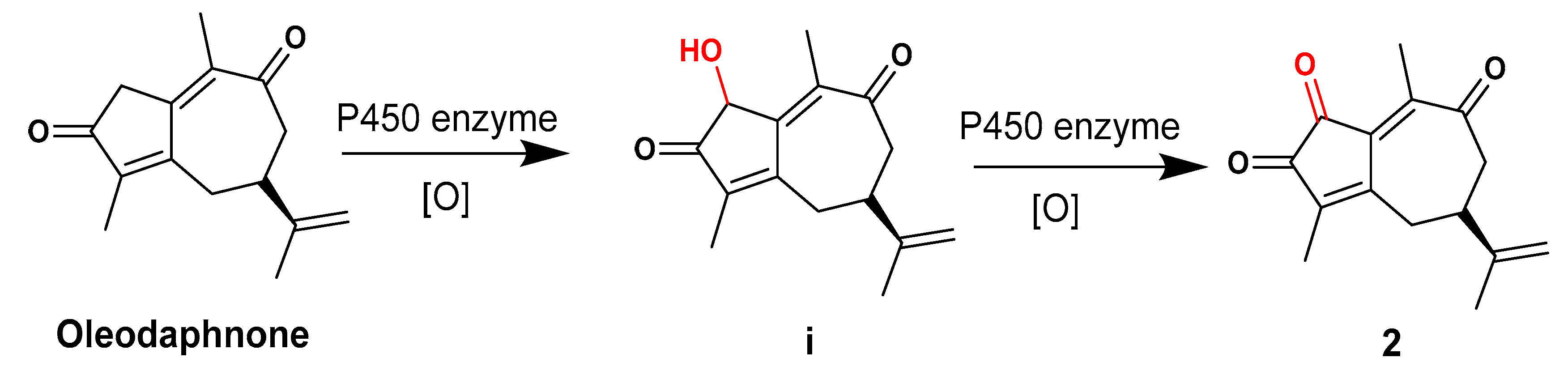

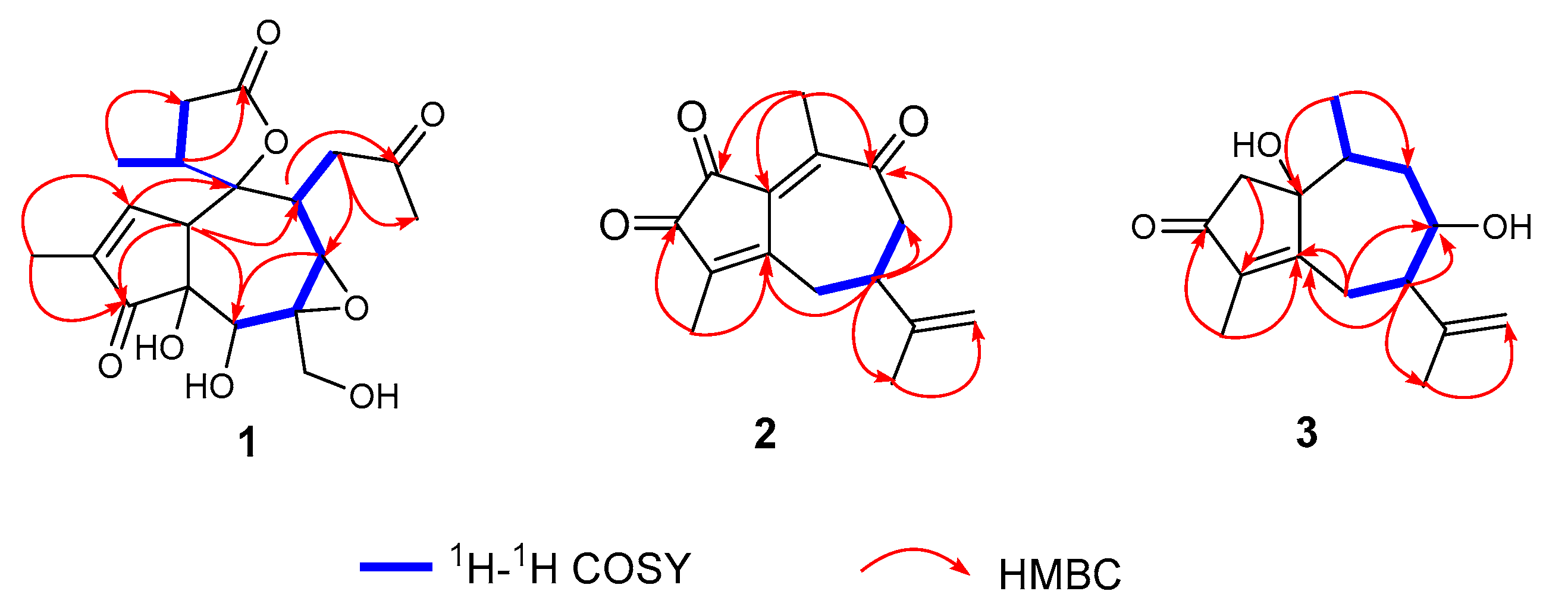

2.1. Structural Elucidation of Three New Compounds (1, 2, and 3)

2.2. Biological Studies

Materials and Methods

1.1. General Experimental Procedures

1.1. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

3.4. Details of New Compounds

3.4.1. Stellerterpenoid A (1)

3.4.2. Stellerterpenoid B (2)

3.4.3. Stellerterpenoid C (3)

3.5. ECD Calculations for 1, 2 and 3

3.6. Determination of NO Production

3.7. Anti-Influenza Virus Assay

3.8. Anti-Tumor Assay

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Credit author statement

Declaration of competing interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Li, J.; Zhao, W.; Hu, J. L.; Cao, X.; Yang, J.; Li, X.R. A new C-3/C-3”- biflavanone from the roots of Stellera chamaejasme L. Molecules 2011, 16, 6465–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.N.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, G.L.; Li, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Weng, X.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.W.; Zhu, X.X. Anti-tumor pharmacological evaluation of extracts from stellera chamaejasme L based on hollow fiber assay. BMC Complem. Altern. M. 2014, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.P.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, H.B. A new lignan from the roots of Stellera chamaejasme. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2012, 48, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, S.S.; Feng, L.Y.; Zhang, D.Y.; Lin, N.M.; Zhang, L.H.; Pan, J.P.; Wang, J.B.; Li, J. In vitro anti-cancer activity of chamaejasmenin B and neochamaejasmin C isolated from the root of Stellera chamaejasme L. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, Q.; Bao, C.H.; Chen, L.T.; Li, X.R. A new dicoumarinyl ether from the roots of Stellera chamaejasme L. Molecules 2014, 19, 1603–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.Z.; Li, J.H.; He, W.; Liu, L.; Huang, D.; Wang, K. High nutrient uptake efficiency and high water use efficiency facilitate the spread of Stellera chamaejasme L in degraded grasslands. BMC Ecol. 2019, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Cheng, M.C.; Zhang, X.Z.; Hong, Z.L.; Gao, M.Z.; Kan, X.X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhu, X.X.; Xiao, H.B. Cytotoxic biflavones from Stellera chamaejasme. Fitoterapia 2014, 99, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Wijeratne, E.M.; Seliga, C.J.; Zhang, J.; Pierson, E.E.; Pierson, L.S., III; VanEtten, H.D.; Gunatilaka, A.A. A new anthraquinone and cytotoxic curvularins of a Penicillium sp. from the rhizosphere of Fallugia paradoxa of the Sonoran desert. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, S.S.; Feng, L.Y.; Zhang, D.Y.; Lin, N.M.; Zhang, L.H.; Pan, J.P.; Wang, J.B.; Li, J. In vitro anti-cancer activity of chamaejasmenin B and neochamaejasmin C isolated from the root of Stellera chamaejasme L. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Feng, W.; Saijo, N.; Ikekawa, T. Antitumor activity of daphnane-type diterpene gnidimacrin isolated from Stellera chamaejasme L, Int. J. Cancer 1996, 66, 268–73. [Google Scholar]

- Asada, Y.; Sukemori, A.; Watanabe, T.; Malla, K.J.; Yoshikawa, T.; Li, W.; Koike, K.Z. Chen, C.H.; Akiyama, T.; Qian, K.D.; Nakagawa-Goto, K.S.; Morris-Natschke, L.; Lee, K.H. Stelleralides A-C, novel potent anti-HIV daphnane-type diterpenoids from Stellera chamaejasme L. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2904–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.X.; Guo, J.J.; Yang, B.J.; Fan, S.R.; Wang, Y.T.; Chen, D.Z.; Hao, X.J. Stelleraguaianone B and C, two new sesquiterpenoids from Stellera chamaejasme L. Fitoterapia 2019, 134, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.F.; Qi, D.D.; Xu, S.; Mao, W. A new 11, 10-guaiane-type sesquiterpenoid from the roots of Stellera chamaejasme Linn. J. Chem. Res. 2021, 45, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Su, J.C.; Liu, Y.H.; Deng, B.; Hu, Z.F.; Wu, J.L.; Xia, R. F.; Chen, C.; He, Q.; Chen, J.C.; Wan, L.S. Stelleranoids A-M, guaiane-type sesquiterpenoids based on [5,7] bicyclic system from Stellera chamaejasme and their cytotoxic activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 115, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.Y.; Hou, Z.L.; Ren, J.X.; Zhang, D.D.; Huang, X. X.; Lin, B.; Song, S.J. Guaiane-type sesquiterpenoids from the roots of Stellera chamaejasme L. and their neuroprotective activities. Phytochemistry 2021, 183, 112628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Ren, J.X.; Li, Y.L.; Yao, G.D.; Song, S.J.; Huang, X.X. Stellerasespenes A-E: Sesquiterpenoids from Stellera chamaejasme and their anti-neuroinflammatory effects. Phytochemistry 2022, 201, 113275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, Y.; Sukemori, A.; Watanabe, T.; Malla, K.J.; Yoshikawa, T.; Li, W.; Kuang, X.Z.; Koike, K.; Chen, C.H.; Akiyama, T.; Qian, K.D.; Nakagawa-Goto, K.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Lu, Y.; Lee, K.H. Isolation, structure determination, and anti-HIV evaluation of tigliane-type diterpenes and biflavonoid from Stellera chamaejasme. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.H.; Tanaka, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Kouno, I.; Duan, J.A.; Zhou, R.H. Biflavanones, diterpenes, and coumarins from the roots of Stellera chamaejasme L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.G.; Park, N.J.; Jegal, J.; Choi, S.; Lee, S.W.; Jin, H.; Kim, S.N.; Yang, M.H. A new flavonoid from Stellera chamaejasme L., stechamone, alleviated 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in a murine model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 59, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Yan, Z.Q.; Guo, H.R.; Yang, J.Y.; Liu, Q.; Jin, H.; Xu, R.; Cui, H.Y.; Qin, B. Phytotoxic flavonoids from roots of Stellera chamaejasme L. (Thymelaeaceae). Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M.; Feng, W. J.; Nishio, K.; Takahashi, M.; Heike, Y. J.; Saijo, N.; Wakasugi, H.; Ikekawa, T. Antitumor action of the PKC activator gnidimacrin through CDK2 inhibition. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 94, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Zhao, Y.; Lee, K.H.; Chen, D.F. Stelleralides D-J and anti-HIV daphnane diterpenes from Stellera chamaejasme, J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2712–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, H.J.; Randy, A.; Yun, J.H.; Oh, S.R.; Nho, C.W. Stellera chamaejasme and its constituents induce cutaneous wound healing and anti-inflammatory activities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; J. Huang, L.; Yuan, F. Y.; Wei, X.; Zou, M. F.; Tang, G. H.; Li, W.; Yin, S. Crotonianoids A-C, three unusual tigliane diterpenoids from the seeds of Croton tiglium and their anti-prostate cancer activity. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 9301–9306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitomi, T.; Yoshihisa, T.; Gisho, H.; Yasuhiro, I.; Ekrem, S.; Erdem, Y. Terpenoids and aromatic compounds from Daphne oleoides ssp. Oleoides. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca Karande, D.; Schmid, A.; Dobslaw, D. Novel cyclohexane monooxygenase from Acidovorax sp. CHX100. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 6889–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Dong, M.Y.; Chang, H.; Han, N.; Yin, J. Guaiane type of sesquiterpene with NO inhibitory activity from the root of Wikstroemia indica. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 99, 103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, K.R.; Cardellina II, J.H.; McMahon, J.B.; Gulakowski, R.J.; Ishitoya, J.; Szallasi, Z.; Lewin, N. E.; Blumberg, P. M.; Weislow, O.S.; Beutler, J. A.; Jr, R.W.B.; Cragg, G.M.; COX, P.A.; Bader, J.P.; Boyd, M.R. A nonpromoting phorbol from the Samoan medicinal plant Homalanthus nutans inhibits cell killing by HIV-1. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35(11), 1978–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.B.; Shao, J.Q.; Zhu, J.X.; Zi, J.C. Chamaej4asnoids A-E, a 2,3 - seco - guaiane sesquiterpenoid with a 5/6/7 bridged ring system and related metabolites from Stellera chamaejasme L. Fitoterapia 2022, 158, 105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.Y.; Zheng, Y.T.; Dai, H.F.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhao,Y. X. Anti-HIV terpenoids from Daphne aurantiaca Diels Stems. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 80254–80263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, T.; Obora, Y.; Tokunaga, M.; Sato, H.; Tsuji, Y. Dendrimer N- heterocyclic carbene complexes with rhodium(I) at the core. Chem. Commun. 2005, 36, 4526–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescitelli, G.; Bruhn, T. Good computational practice in the assignment of absolute configuration by TDDET calculations of ECD spectra. Chirality 2016, 28, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, T.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Hemberger, Y.; Pescitelli, G. SpecDis, Version 1.71. Berlin, Germany; 2017.

- Cao, L.; Li, R.T.; Chen, X.Q.; Xue, Y.; Liu, D. Neougonin A inhibits lipopoly- saccha-ride-induced inflammatory responses via downregulation of the NFkB signaling pathway in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Inflammation 2016, 39, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Quan, L.Q.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Li, H.M.; Chen, X. Q.; Li, R.T.; Liu, D. Exploring the anti-influenza virus activity of novel triptolide derivatives targeting nucleoproteins. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 129, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiev, P.; Kim, J.W.; Sung, S.J.; Song, H.H.; Choung, D.H.; Chin, Y.W.; Lee, H.K.; Oh, S.R. Ingenane-type diterpenes with a modulatory effect on IFN - γ production from the roots of Euphorbia kansui. Arch Pharm. Res. 2012, 35, 1553–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.48 d (1.8) | 2.57 d (18.2) | |

| 2.34 d (18.2) | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | 4.31 s | 3.03 d (17.2) | 2.69 d (6.7) |

| 2.89 d (6.5) | |||

| 6 | 2.76 m | 3.00 m | |

| 7 | 3.24 d (6.0) | 2.94 m | 3.69 m |

| 2.85 m | |||

| 8 | 3.57 ddd (10.6, 5.4, 2.4) | 2.20 ddd (13.8, 10.0, 3.5) | |

| 1.75 ddd (13.8, 5.4, 3.5) | |||

| 9 | 2.29 m | ||

| 10 | 3.47 d (2.6) | ||

| 11 | 2.74 m | ||

| 12 | 3.09 dd (18.1, 8.1) | 4.81 s | 4.79 s |

| 2.27 dd (18.1, 4.4) | 4.80 s | 4.76 s | |

| 13 | 1.80 s | 1.80 s | |

| 14 | 2.83 dd (18.1, 10.6) | 1.95 s | 0.85 d (7.2) |

| 2.63 dd (18.1, 2.6) | |||

| 15 | 1.85 s | 1.64 s | |

| 16 | 2.19 s | ||

| 17 | 1.18 d (7.0) | ||

| 18 | 1.78 s | ||

| 19 | 3.85 s |

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 158.3 | 202.6 | 50.3 |

| 2 | 137.7 | 204.3 | 208.3 |

| 3 | 209.8 | 146.1 | 138.9 |

| 4 | 76.2 | 165.1 | 173.8 |

| 5 | 75.9 | 36.3 | 32.2 |

| 6 | 66.0 | 40.3 | 51.3 |

| 7 | 58.8 | 50.6 | 70.5 |

| 8 | 40.3 | 202.6 | 40.8 |

| 9 | 91.8 | 132.6 | 37.9 |

| 10 | 51.0 | 145.9 | 82.2 |

| 11 | 39.2 | 148.9 | 149.0 |

| 12 | 38.9 | 111.3 | 112.8 |

| 13 | 177.9 | 20.4 | 19.9 |

| 14 | 42.6 | 17.3 | 15.6 |

| 15 | 209.2 | 8.8 | 7.9 |

| 16 | 30.2 | ||

| 17 | 18.0 | ||

| 18 | 10.0 | ||

| 19 | 63.6 |

| Compds | aIC50(μM) | bCC50(μM) | Compds | IC50(μM) | CC50(μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >50 | cNT | 6 | >50 | NT |

| 2 | >50 | NT | 7 | >50 | NT |

| 3 | >50 | NT | 8 | >50 | NT |

| 4 | >50 | NT | 9 | >50 | NT |

| 5 | 24.76±0.4 | >50 | dL-NMMA | 12.30±3.4 | >50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).