1. Introduction

Accuracy of the laboratories results is critical when it’s come to clinician’s decision to treat patients or assess efficaciousness of drugs or vaccine products in clinical research setting.

This challenge is more pronounced in the laboratories of resource limited countries (LRLC) where a synergic combination of many factors is playing such role us, lack of limited financial resources that lead to inadequate infrastructure, maintenance of equipment, training of competent personnel etc.

The Groupe de Recherche Action en Santé (GRAS) is a private research organization nurturing the vision of becoming a hub of excellence in biomedical research in West Africa. One of its main missions is to design, carry out clinical, operational and basic research studies to identify new tools for the control of target diseases while monitoring the effectiveness of the existing ones. Towards this end, GRAS has set up a technical platform for ensuring a highly efficient clinical laboratory. In the context where accreditation bodies are not yet widespread and accessible to all institutions, external proficiency testing (EPT) maybe a good alternative for clinical laboratories to build a strong quality system with satisfactory performance [

1,

2].

Since 2020 to keep with high quality standard, GRAS has enrolled its laboratories to external quality control scheme with organizations holding an international recognition. Thus, the clinical laboratory has been registered in PT with the College of American Pathologists (CAP) for hematology, clinical chemistry and blood parasite surveys while for malaria diagnosis by microscopy, the Clinical Laboratory Service/National Institute for Communicable Diseases (South Africa) (NICD) blood parasites proficiency Testing Scheme was used.

This manuscript presents the results of 5 years of continued participation of GRAS clinical laboratory in both PT schemes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Clinical Laboratory of GRAS

The main laboratory is located in Ouagadougou, the capital city of Burkina Faso and two secondary satellite labs research unites are based respectively at 100 km (Health district of SABOU- Boulkiemdé region) and ~500km (Health District of Banfora- Cascades region) from the capital city. The GRAS biomedical laboratory is structured around two main platforms: a) a clinical biology platform which aims to investigate key laboratory tests relevant for clinical trials to explore the safety of products (vaccine and drug) under investigation and for the medical care of study volunteers and b) a biological research platform with the main goal of clear understanding of pathogenesis of infectious diseases in order to direct the development of new control tools. This laboratory essentially offers a support service for clinical trials and research activities requiring medical care for patients. It is equipped with standard calibrated instruments for routine biomedical analysis (biochemistry, haematology, bacteriology, immunology, parasitology, etc.…) and for in-depth biological analysis on the pathogenesis of major infectious diseases including emerging diseases (Cellular immunology, Gene sequencing, Genotyping...) vectors and other intermediate hosts. Each instrument has a preventive maintenance plan by a qualified technician at least once a year.

The laboratory staff is mainly composed up of biotechnologists, biologists, pharmacists with biological background. They are all regularly trained for Good clinical Practices (GCP) as well as Good Clinical and Laboratory Practices (GCLP). In addition, in-house competency assessment is done annually.

Each biological test is done against internal controls for routine practices and research experiments.

The laboratory is often evaluated by sponsors before the launch of clinical trials. The staff is retrained whenever required.

Architecture of the External Quality Control Schemes

Since 2020, GRAS has joined two proficiency schemes to assess the performance of laboratory quality system in one hand with College of American Pathologists (Blood pathogens, biochemistry and hematology) and in another hand to assess the intrinsic competence of microscopists skills in malaria and other blood parasite diagnosis with the Clinical Laboratory Services of South Africa.

Prior to receive the PT specimens, each participating laboratory has to register online early in December each year through CAP or CLS platforms and pays out the corresponding fees.

2.2. PT with College of American Pathologists (CAP)

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) program is the largest external quality assessment program in the world. As such, it provides an unparalleled selection of challenges and offers the largest database in existence for interlaboratory comparison. Performance on CAP Surveys is not the sole indicator of a laboratory’s performances. Rather, PT indicators define what is needed to assess, manage, and improve quality [

3].

PT samples are couriered three times a year (quarterly) to participating laboratories and the results are generally returned three weeks after sample shipping.

2.2.1. Microscopy

For microscopy, submitted specimen are thick and thin blood films (4 or 5 per shipment) stained with Giemsa and mounted with strip to protect them for multiple use, or photographs also called ̎whole slide images ̎(WSI).WSI has been proved to be good tools for training in several graduate education setting [

4]. The target organisms are malaria parasites and other blood parasites The procedure in preparing these slides also follows the routine laboratory approved procedures following WHO manual and safety requirement of the services providers [

5]. At GRAS, the blood smears are assessed independently by each laboratory biotechnologist and the results collected and submitted by a third person (usually the head of the lab.) not involved in the slide reading process.

2.2.2. Clinical Chemistry and Hematology

Biochemistry, Haematology and electrolytes assessment are the critical parameters for clinical studies (drugs and vaccine). The details are presented in

Table 1. Five [

5] samples are received and analyzed for haematology and biochemistry assessment during each evaluation timepoint. The results from the analysis are submitted online via a dedicated platform. The samples are collected from tree different study satellite sites (Banfora, Sabou and Ouagadougou) as part of the institutional internal control systems. The equipments used for biochemistry and hematology are respectively, INDIKO Plus 864, SPIN 200E and Mindray BS230 and Sysmex XN330 and Sysmex XN550. For biochemistry analyzer, INDIKO Plus 864, SPIN 200E and Mindray BS230 were used. The Laboratories processed and analyze PT/EQA samples in the same way as in routine clinical patient specimens based on their internal approved SOP.

2.2.3. Sample Evaluation and Scoring

After submission for evaluation, the laboratory’s individual performance is graded using specified CLIA scoring criteria with either a peer group or an assigned target determined by selected referee laboratories.

Results obtained during different timepoint of the PT evaluation in the course of the years evaluation were input into an Excel worksheet to enable statistical computations and analysis. Comparison of accuracy and performance scores were then plotted to estimate either the participants or the laboratory accuracy and performance level through the years of evaluation.

The College of American Pathologist PT evaluation (Parasitology, hematology and biochemistry) is based on sensitivity and specificity of the data obtained during each time point evaluation.

A cut off score of more or equal to 80% is required to have a performance score of “satisfactory”.

For the CLS microscopy PT assessment, each laboratory technician was assigned a grading according to the results submitted based mainly on malaria parasite detection, identification and P. Falciparum asexual parasites counting (see

Table 2).

2.3. PT with Clinical Laboratory Services (CLS)

This PT Scheme is produced by the Parasitology Reference Laboratory, NICD, NHLS, South Africa and focuses on microscopy. PT samples are couriered out three times a year to the reference laboratory and results are generally received four weeks after shipping. The results include individual reports and commentaries.

In total, 20 specimens are required in the evaluation. These are thick and thin blood films stained with Giemsa. The thick blood films are mounted with strip to allow for multiple readings.

This scheme assesses individual microscopist performance as opposed to laboratory performance. It is therefore critical that microscopists work independently. Individual participant results should be submitted to a designated non-participating colleague(s) who will collate responses for the laboratory and submit to CLS/NICD via a dedicated platform.

Microscopists are graded on the accuracy of malaria species identification and parasite counting. Parasite counts are scored as acceptable if they are within 25% of the true count (according to the validators used by CLS/NICD). The competence level achieved is based on whether the microscopist obtains the right results for parasite detection, parasite species identification and

P. Falciparum asexual parasite counting. For example, to reach «Expert» certification, a microscopist must achieve 90% or more accuracy for parasites detection, 90% or more accuracy for speciation, and 50% or more of the parasite counts must be within 25% of the true count (referee). The competences grading is summarized in

Table 2 below. The score of the parasite count within 25% of true count (%) always determine the level of competency of the reader.

3. Results

During the five [

5] years participation, the parasitological lab was evaluated 12 time instead of 15. The three missing evaluation happened in 2022 (Q1 and Q2) and 2024 (Q1) due to late registration of the laboratory in the CAP system. For the same raison, haematology and biochemistry missing evaluations happened on Q1 (first PT evaluation) in 2021, 2022 and 2024 in 2022 and 2024 on Q1 respectively for haematology and biochemistry. Summary of the number of performed PT during the years follow up is done in

Table 3.

3.1. Parasitological Laboratory Accuracy Score from 2020 to 2024 of CAP PT Evaluation

The parasitological laboratory accuracy score performance during the 5 years evaluation was successful (≥ 80%). No unsatisfactory score was recorded over the 5 years PT participation. The overall CAP performance rate of the laboratory was 94,16% ranging from 83,33% to 100%. Detail are shown in the

Table 4 below.

3.2. Haematology Labozratory Accuracy Score from 2021 to 2024 of CAP PT Evaluation

The main parameters evaluated in haematology are listed in the

Table 1. During the 4 years participation in the CAP PT evaluation, the score rate obtained during the first (Q1), second (Q2) and third (Q3) quadr-month evaluation was always 100% for all the assessed parameters.

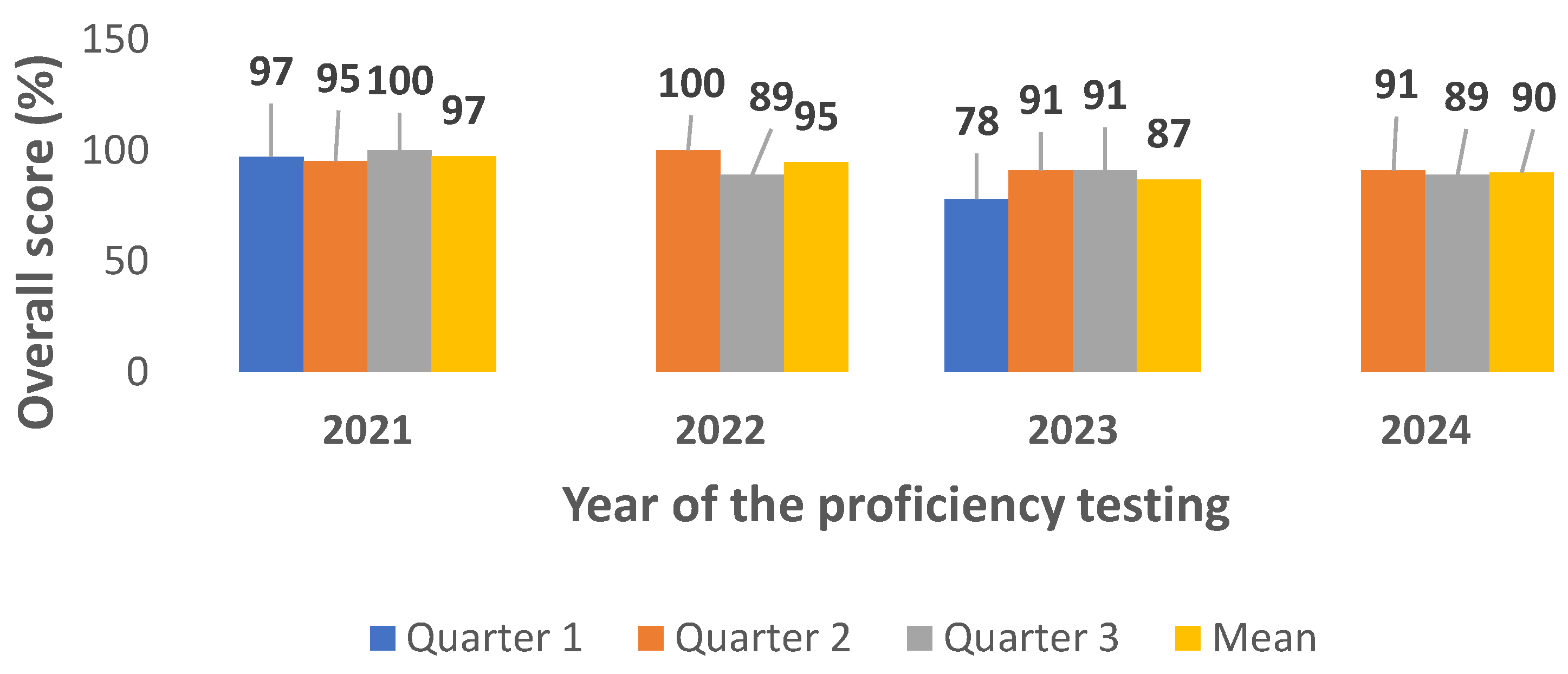

3.3. Biochemistry Laboratory Accuracy Score from 2021 to 2024 of CAP PT Evaluation

The main parameters evaluated in biochemistry are listed in the

Table 1. Additional parameters such as triglyceride, uric acid, cortisol, thyroxine free (Th4, Free) HCG, TSH were also assessed. During the 4 years participation in the CAP PT evaluation, the score rate of the main parameters requested during clinical studies was successful except for total bilirubin (Q2, year 2021 and year 2022), calcium (Q3, year 2023), total cholesterol, creatinine, glycose and sodium (Q2, year 2022), albumin, chloride, creatinine, glycose (Q1 year 2023) and magnesium (Q2 year 2023). The overall score performance was 92,62% ranging from 78% to 100% (

Figure 1).

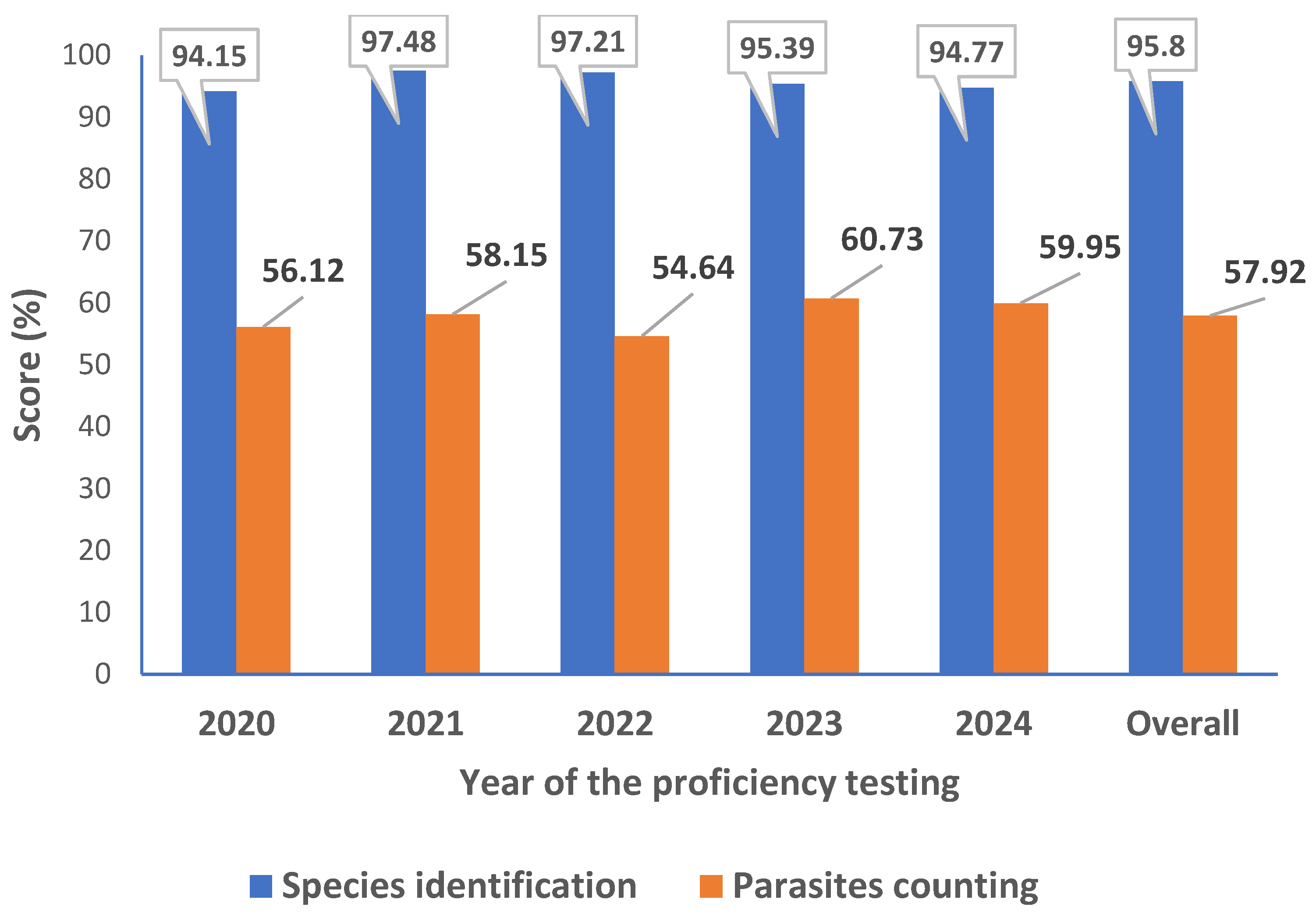

3.4. Parasites Identification and Counting Score Rate from 2020 to 2024 of CLS PT Evaluation

CLS PT evaluation is similar to WHO External Competency Assessment for Malaria Microscopy (ECAMM) based essentially on malaria parasite identification and P. Falciparum asexual parasites counting. The used of 20 slides instead of 5 as compared to the CAP and the score rate required for qualification as “reader” has putting additional valuable accent to the expertise of the laboratory and also the individual laboratory technician competence assessment. The number of laboratory technicians participating in this PT evaluation varied for each timepoint of the PT evaluation depending mainly on the workload. In total, 31 laboratory technicians participated in these CLS PT, with a total of 15 participations through the five [

5] years evaluation. The overall performance goes from 94,15% to 97,48% for parasites detection and identification to 54,64% and 60,73% for parasites counting. Detail is given in the

Figure 2.

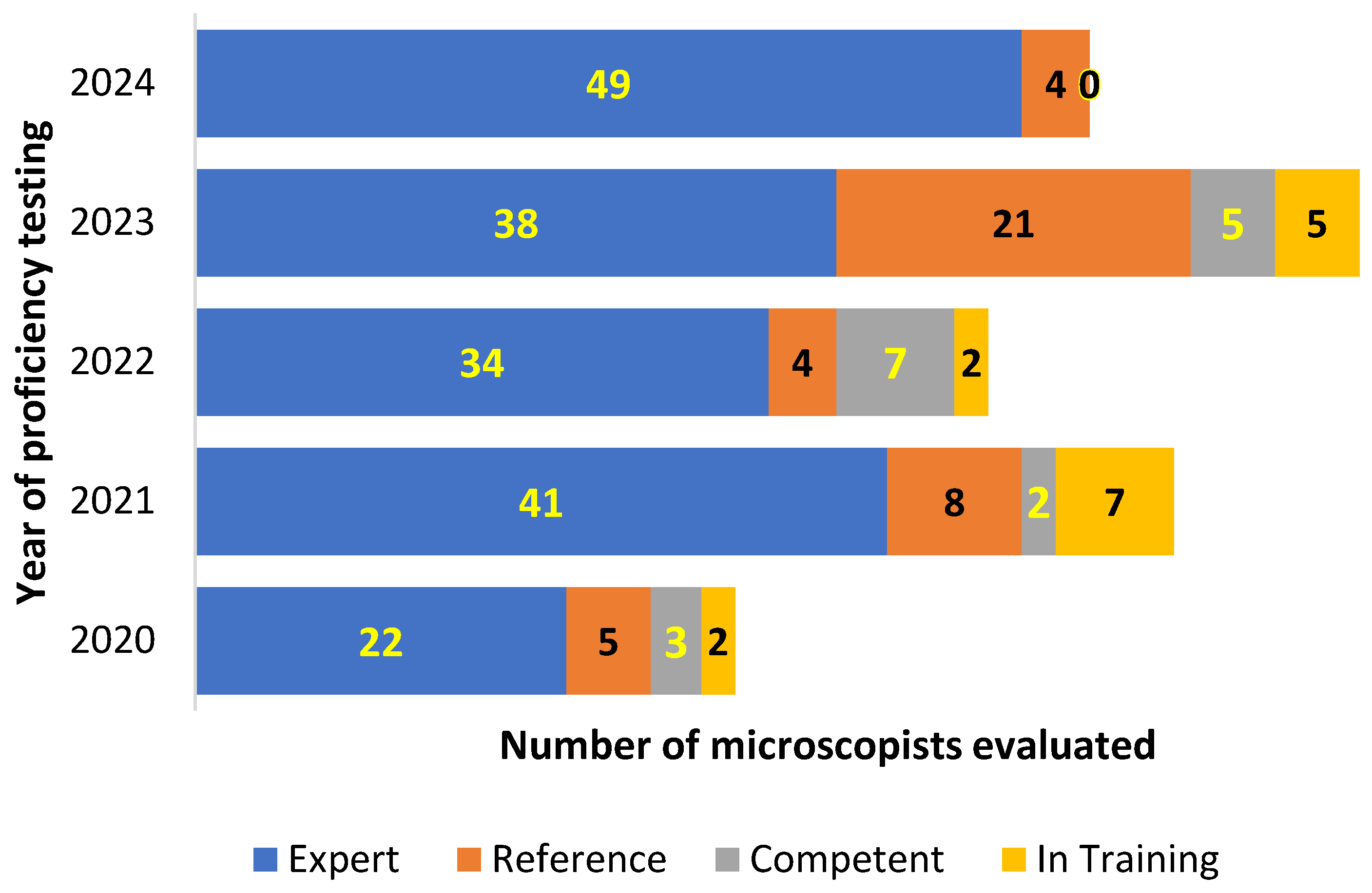

In addition to the main focus on malaria parasite identification and counting, the CLS also evaluate participants individual performance on other blood parasites detection and identification. The combination of parasites detection, identification and P. falciparum asexual parasite counting is used to grading participants as shown in the

Figure 3.

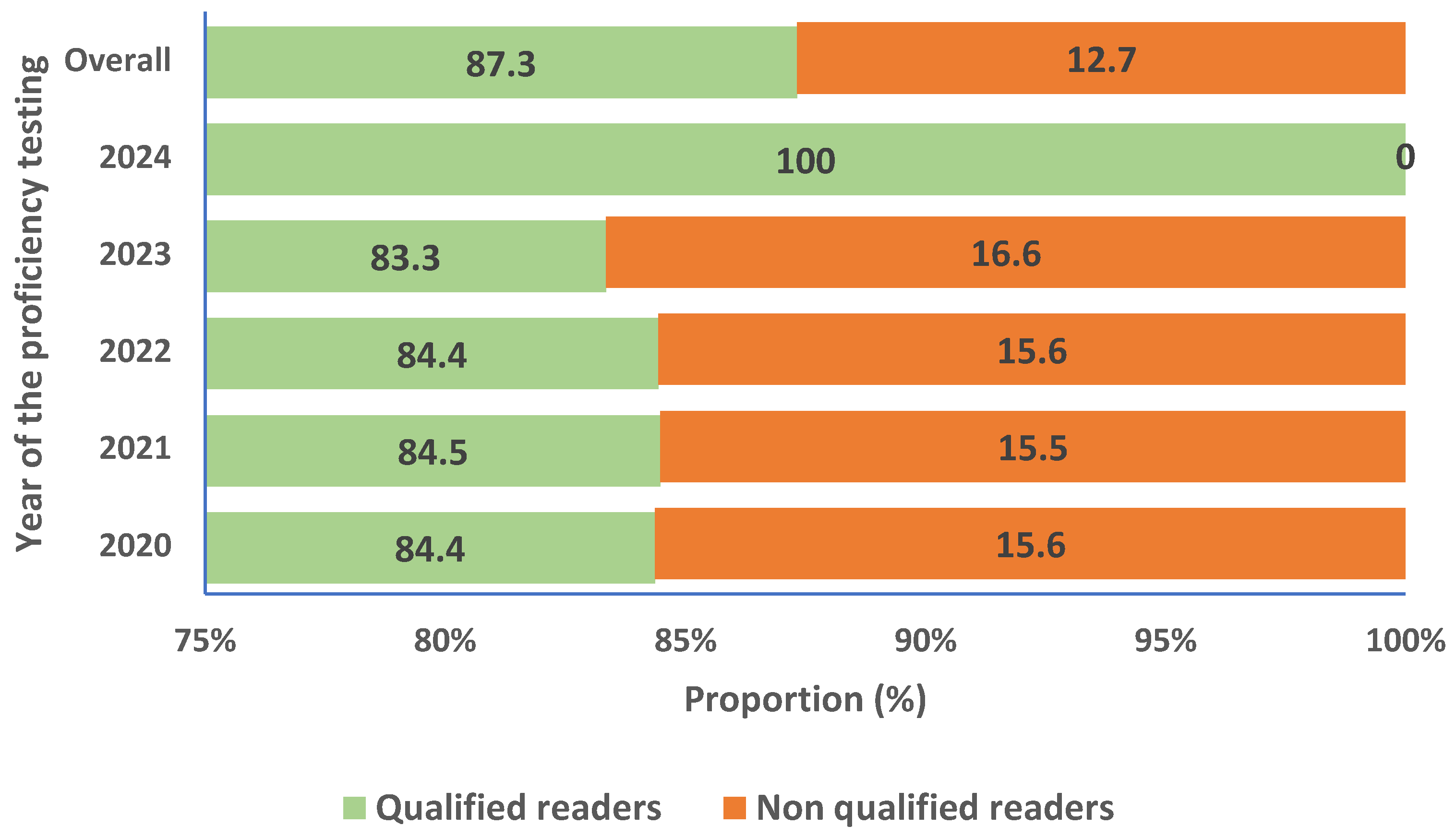

We also evaluated the proportion of microscopists shifting from qualified reader to non-qualified or vice versa during the evaluation period. In total, 12,67% of participants initially considered as qualified readers changed status to become non-qualified during at least one evaluation timepoint. Details are given in the

Figure 4.

4. Discussion

In clinical research laboratory, accurate data is a key factor for clinical decision. Participating in an external quality assessment such us proficiency testing (PT) is a requirement of accreditation and ISO 15189: 2022 for medical laboratories [

6]. Nevertheless, producing accurate and confident results through PT is a challenge for clinical laboratory in developing countries. The main challenge reside in the lack or inadequate allocation resources to the laboratory services [

7]. Fortunately, during the last 15 years, this paradigm has changed with the investment of governments and private health sectors through the three main pathways programmes of implementing quality management system (QMS) launched in 2009 by WHO- AFRO such as Strengthening Laboratory Management Towards Accreditation (SLMTA), Stepwise Laboratory Improvement Process Towards Accreditation (SLIPTA) and Laboratory Quality Stepwise Implementation (LQSI) [

8]. The Groupe de Recherche Action en Santé (GRAS) is a private health research organization created in 2008 with main aim to become a pole of excellence in biomedical research in West Africa. These five [

5] years of his participation to these external PT programmes was a learning journey with key lessons learnt that we are willing to share with the research community facing the same challenges.

4.1. Why Participating in a Proficiency Testing Program?

Accuracy of laboratory results is crucial in all aspect of the health system rung. In clinical research, almost all clinical decisions taken by the physicians for patients care, relied on the clinical laboratory results [

9]. Indeed, participation of a volunteer in a clinical study (drugs or vaccine assessment) is based mainly on the lab results that give the green line of any safety inclusion and follow up of that volunteer. Any lab results error will impact all study procedures and expose safety of the participants. The need of putting in place a robust quality system became mandatory and required special attention. The first step of quality in any clinical lab that guaranty the reproductivity and the accuracy of the results used for patient’s management is the use of standardized procedures. But for objective checking of laboratory’s performance, WHO recommend the use of external agency [

10]

4.2. Is There Any Pre-Requisite for a Lab to Engage into a PT Program?

Engagement of a clinical laboratory into a PT scheme required a basic and fundamental organization based mainly on the 12 quality system essentials (QSEs) delineated by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [

11]. Out of these QSEs, a strong Quality management System (QMS) has to be in place. A laboratory quality management system is a systematic, integrated set of activities to establish and control the work processes from preanalytical through postanalytical processes, manage resources, conduct evaluations, and make continual improvements to ensure consistent quality results. Approaches to quality management in clinical microbiology were described previously by Bartlett et al. earlier in 1967 [

12]. At the Groupe de Recherche Action en Santé (GRAS), a QMS has been set up since 2020 covering almost all aspects of the institution including laboratory activities. Each single lab activity is guided by a written approved SOP. The maintenance of the equipment is done accordingly either by manufacturer recommendation or based on internal experience of the used of that equipment. Laboratory technicians are regularly trained on GCLP and all SOPs before operating lab activities.

4.3. How to Sustain the Engagement and Good Skills in Diagnosis of the Lab Staff?

Sustaining engagement of a clinical laboratory staff skill require management through training and good organization. A leadership and integrated institutional quality management system is essential, although all this is highly dependent on financial resources allocated [

13]. To overcome these challenges, accent was put in the continuous training and follow up of the lab staff for each specific lab activities.

Concerning microscopical PT challenge, we know that the drawback to blood smear microscopy for the diagnosis of malaria and other blood parasite is that, it is operator-dependent and requires initial and continuous training to maintain a high quality of testing. Such quality assurance practices are often difficult to implement in resource-poor countries [

14]. Microscopy performed on stained films of peripheral blood for detection, identification and quantification of malaria parasites is an essential reference standard for clinical trials of drugs, vaccines and diagnostic tests for malaria [

15]. During the 5 years participation in the CAP PT, the parasitological laboratory has experienced a very good score, with 76,66% for other blood parasites detection and identification rate, and 100 % for malaria parasites speciation and detection of negatives slides. The sensitivity and specificity for malaria parasites assessment was 100% over the course of the 5 years participation. This high score is mainly due to a strong internal quality management plan set up and implemented several years in this laboratory. The continuous refresh training of the laboratory staff and rigorous follow up of the operating procedures are fundamental in this aspect. In a study conducted by Mary and all from 2015-2019 with the aim to see the impact of malaria diagnostic refresher training programme on competencies and skills in malaria diagnosis among medical laboratory professionals, showed that participants’ competency level and skill to perform malaria microscopy (speciation, identification, parasite quantification and detection of malaria parasites) increased by approximately two folds after the training compared to the no-training scenario [

16]. The ability of the medical laboratory professionals to correctly detect malaria parasites increased significantly from a median score of 64% prior to the training to 87% after the training. The competencies of the medical laboratory scientists to correctly identify malaria parasite species and quantify the number of malaria parasites increased significantly from a median score of 17% and 20% pre-test to 78% and 50% post-test, respectively. Application of Good Clinical Laboratory Practices (GCLP) improved the success rate in a PT surveys from 58% in 2009 to 88% in 2010 and also decreased the error rate on PT by 35% in a study conducted in Ghana by Ibrahim et al. in 2012 [

17].

At individual level, the CLS PT evaluation on malaria and other blood parasite have shown a higher score of performance over the 5 years evaluation with a high ability for parasites detection, identification and parasites counting. The level of expertise “qualify technicians as readers” range from 83,33% to 100% during the 5 years evaluation. That level of expertise is in the line of WHO standard where any treatment of malaria case should base on evidence demonstration of the presence of the parasite in the patient blood and also according to drugs protocol assessment [

18].

During the 5 years evaluation of the CLS, the capacity of malaria parasite detection and identification was always 100%. The counting was the main concerning factor, affecting the grading level of laboratory technicians, although the means parasites counting was always above 50%, as recommended by WHO External Competence Assessment (ECA) [

19] . In dead, in a context of multi-parasitic infection setting where, in addition to malaria infection, cohabiting several parasites such as filariasis, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, babesia, as well as bacterial and fungal [

20,

21,

22], it is essential to have highly skilled laboratory technician capable to discriminate and count those parasites [

23,

24]. A higher number of qualify laboratory technicians as readers across the study sites has been maintained in the benefit of the patients. That lead to confident results and was well appreciated during studies monitoring by peer’s review. The trend of having an increase number of “non-readers” shown in the

Figure 4 (from 8% to 16.6%) is mainly due to the new staff recruited during the years of evaluation. As we know, acquisition of skill for malaria parasites diagnostic require time and efforts for training [

15].

The participation of GRAS clinical laboratory in EPT has shown a great achievement in term of setting up and consolidated methods and processing studies volunteers’ sample. The 100% accuracy obtained over the 4 years participation of haematology laboratory indicate the high-performance level of the tested automates, the comparability of data between automates, but also the robustness of the internal SOP used. That led to confident results in the benefit of studies volunteers and clinician’s in charge of patients care. Indeed, in a study conducted by Chaudhry and all in 2023, it has been clearly demonstrated that 70–75% of medical diagnoses are obtained via clinical laboratory reports, making laboratory service quality directly impact healthcare quality [

9]. For the assessment of drugs or vaccine safety, biochemistry parameters are part of the crucial indicators. In fact, the direct effect or sides effects of investigational products may have major impact on some organs such us liver function, kidney, electrolytes disorder, heart lift, blood gas, and so on. During the PT’s evaluations, special attention was address to those parameters. As shown on the

Figure 1, the overall biochemistry PT score performance was 92,62% ranging from 78% to 100% despite issue face with some parameters such as bilirubin, calcium, total cholesterol, creatinine, glycose, sodium, albumin, chloride, creatinine, and magnesium on years 2022 and 2023. Internal investigations have shown that these unsatisfactory results were mainly due to technical issue and the non-specificity of PT tests to the various manufactured biochemistry automates used by our Clinical laboratory.

Indeed, in a study conducted by Tingting Li et al. In 2019, PT tests failure types were distributed as follows, per error group: Clerical, 10.2%; Methodological, 16.2%; Equipment, 23.6%; Technical, 37.4%; PT Evaluation, 0.5%; Unexplained, 11.5%; and Other, 0.7%. Reasons unique to the PT process accounted for 15.6% of all reasons [

25].

Another hurdle for the sustainability participation and implementation of an EQA program is the allocation of sufficient budgets and resources [

26]. Hopefully during the 5 years participation, the PT fees were always afforded by the institution financial accountability service. All other likely drawback that may affected the outcome of the PT such as laboratory equipment and consumables, EQA sample management, logistics and supply chain of EQA samples were all integrated in a strong internal quality management system (IQMS) as a main objective of the institution.

5. Conclusions

The Proficiency testing has demonstrated value as an important laboratory quality assurance tool to improve the skills in term of diagnosis of malaria parasites and other blood parasites of the lab technicians and the quality of the results generated by automates during clinical studies. It has helped laboratories identify issues related to test design and performance. In addition, the ability to compare laboratory performance with others, using the same or different methods on identical samples, has highlighted issues related to test methodology or interpretation and helped for development of best practice guidelines and standard policy. Beyond individual motivation of lab technicians, the overall outcome of the PT results has reinforced the confidence to the lab results generated during the enrolment and follow up of the studies patients, hence the credibility of the partners and the research community to GRAS research findings.

Author Contributions

AD: IN, NH, ATK, AO and ABT were involved in the design of the study, Data interpretation, and defining the content for the manuscript. AD, IN, NH, AO, and SBS were involved in data collection, while AD, ABT, NH, and IN conducted the data analysis. AD, NH, IN and ABT were involved in writing the manuscript. All of the authors had full access to data in the study, discussed the results, critically reviewed the draft manuscript, and agreed on the final version. AD, the corresponding author, had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pr Sodiomon B SIRIMA Director of the GRAS and the GRAS Financial Department for the support over the 5 years PT evaluation. We also thank all GRAS laboratory technicians who rigorously participated in the PT evaluations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GRAS |

Groupe de Recherche Action en Santé |

| PT |

Proficiency Testing |

| CAP |

College of American Pathologist |

| CLS |

Clinical Laboratories services |

| ECAMM |

External Competency Assessment for Malaria Microscopy |

| EPT |

External Proficiency Testing |

| Pf |

Plasmodium Falciparum |

References

- Earley MC, Astles JR, Breckenridge K. Practices and Perceived Value of Proficiency Testing in Clinical Laboratories. J Appl Lab Med. janv 2017;1(4):415-20.

- Wasniewski M, Laurentie M, Rizzo F, Servat A, Aubert M, Cliquet F. Proficiency test for rabies serology: A design complying with international standards for a reliable assessment of participating laboratories. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 11 déc 2019;13(12): e0007824. [CrossRef]

- College of American Pathologist. Proficiency Testing Manual. In Northfield, Illinois 60093-2750; 2017. p. 34.

- Pantanowitz L, Szymas J, Yagi Y, Wilbur D. Whole slide imaging for educational purposes. J Pathol Inform. 20 déc 2012; 3:46. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Methods manual: Microscopy for the detection, identification and quantification of malaria parasites on stained thick and thin blood films in research settings. 2015.

- Nkengasong JN, Nsubuga P, Nwanyanwu O, Gershy-Damet GM, Roscigno G, Bulterys M, et al. Laboratory Systems and Services Are Critical in Global Health. Am J Clin Pathol. sept 2010;134(3):368-73. [CrossRef]

- Nkengasong JN, Birx D. Quality matters in strengthening global laboratory medicine. Afr J Lab Med. 3 nov 2014;3(2):239. [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo CO, van der Puije B, Maina M, Mekonen T, Diallo S, Datema T, et al. Examining 7 years of implementing quality management systems in medical laboratories in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. févr 2023;28(2):126-35. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry AS, Inata Y, Nakagami-Yamaguchi E. Quality analysis of the clinical laboratory literature and its effectiveness on clinical quality improvement: a systematic review. J Clin Biochem Nutr. sept 2023;73(2):108-15. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Overview of external quality assessment (EQA). WHO. module 10. avr 2016; content sheet 10-1.

- Wayne, P. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 4th ed. CLSI document QMS01-A4. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R. C. Experience with a quality control program in a clinical laboratory. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology,.

- Badrick T. Quality Leadership and Quality Control. Clin Biochem Rev. août 2003;24(3):81-93.

- Geneva, World Health Organization. Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance: Results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 8 (2016–2018). 2018;

- Oyegoke OO, Maharaj L, Akoniyon OP, Kwoji I, Roux AT, Adewumi TS, et al. Malaria diagnostic methods with the elimination goal in view. Parasitol Res. 2022;121(7):1867-85. [CrossRef]

- Tetteh M, Dwomoh D, Asamoah A, Kupeh EK, Malm K, Nonvignon J. Impact of malaria diagnostic refresher training programme on competencies and skills in malaria diagnosis among medical laboratory professionals: evidence from Ghana 2015–2019. Malar J. 8 juin 2021; 20:255. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim F, Dosoo D, Kronmann KC, Ouedraogo I, Anyorigiya T, Abdul H, et al. Good Clinical Laboratory Practices Improved Proficiency Testing Performance at Clinical Trials Centers in Ghana and Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 29 juin 2012;7(6): e39098. [CrossRef]

- Worges M, Whitehurst N, Saye R, Ndiaye D, Yamo E, Yukich J. Performance Outcomes from Africa-Based Malaria Diagnostic Competency Assessment Courses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. avr 2019;100(4):851-60. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization 2016. Malaria Microscopy Quality Assurance Manual – Version 2. Vol. Version 2.

- Pollitt LC, MacGregor P, Matthews K, Reece SE. Malaria and trypanosome transmission: different parasites, same rules? Trends Parasitol. mai 2011;27(5):197-203. [CrossRef]

- Lee WC, Cheong FW, Amir A, Lai MY, Tan JH, Phang WK, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi: the game changer for malaria eradication. Malar J. 3 mai 2022;21:140. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues CM, Valadares HMS, Francisco AF, Arantes JM, Campos CF, Teixeira-Carvalho A, et al. Coinfection with Different Trypanosoma cruzi Strains Interferes with the Host Immune Response to Infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. oct 2010 [cité 26 juin 2024];4(10). Disponible sur: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2953483/. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf S, Kao A, Hugo C, Christophel EM, Fatunmbi B, Luchavez J, et al. Developing standards for malaria microscopy: external competency assessment for malaria microscopists in the Asia-Pacific. Malar J. 24 oct 2012; 11:352. [CrossRef]

- Slater L, Ashraf S, Zahid O, Ali Q, Oneeb M, Akbar MH, et al. Current methods for the detection of Plasmodium parasite species infecting humans. Curr Res Parasitol Vector-Borne Dis. 19 mars 2022;2:100086. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Zhao H, Zhang C, Wang W, He F, Zhong K, et al. Reasons for Proficiency Testing Failures in Routine Chemistry Analysis in China. Lab Med. 1 janv 2019;50(1):103-10. [CrossRef]

- Carter, JY. External quality assessment in resource–limited countries. Biochem Medica. 15 févr 2017;27(1):97-109. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).