Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data Sources

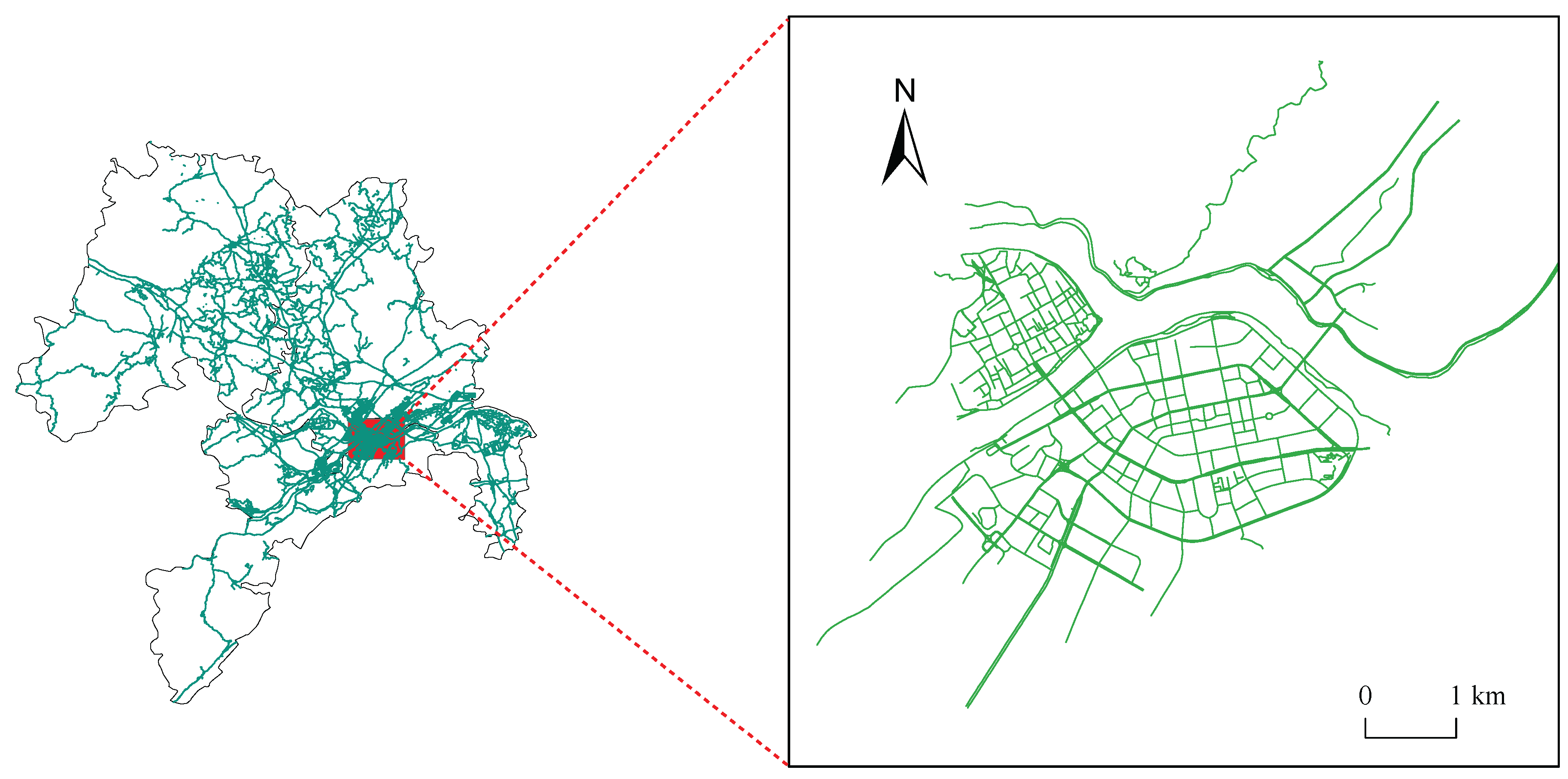

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Road Network Data

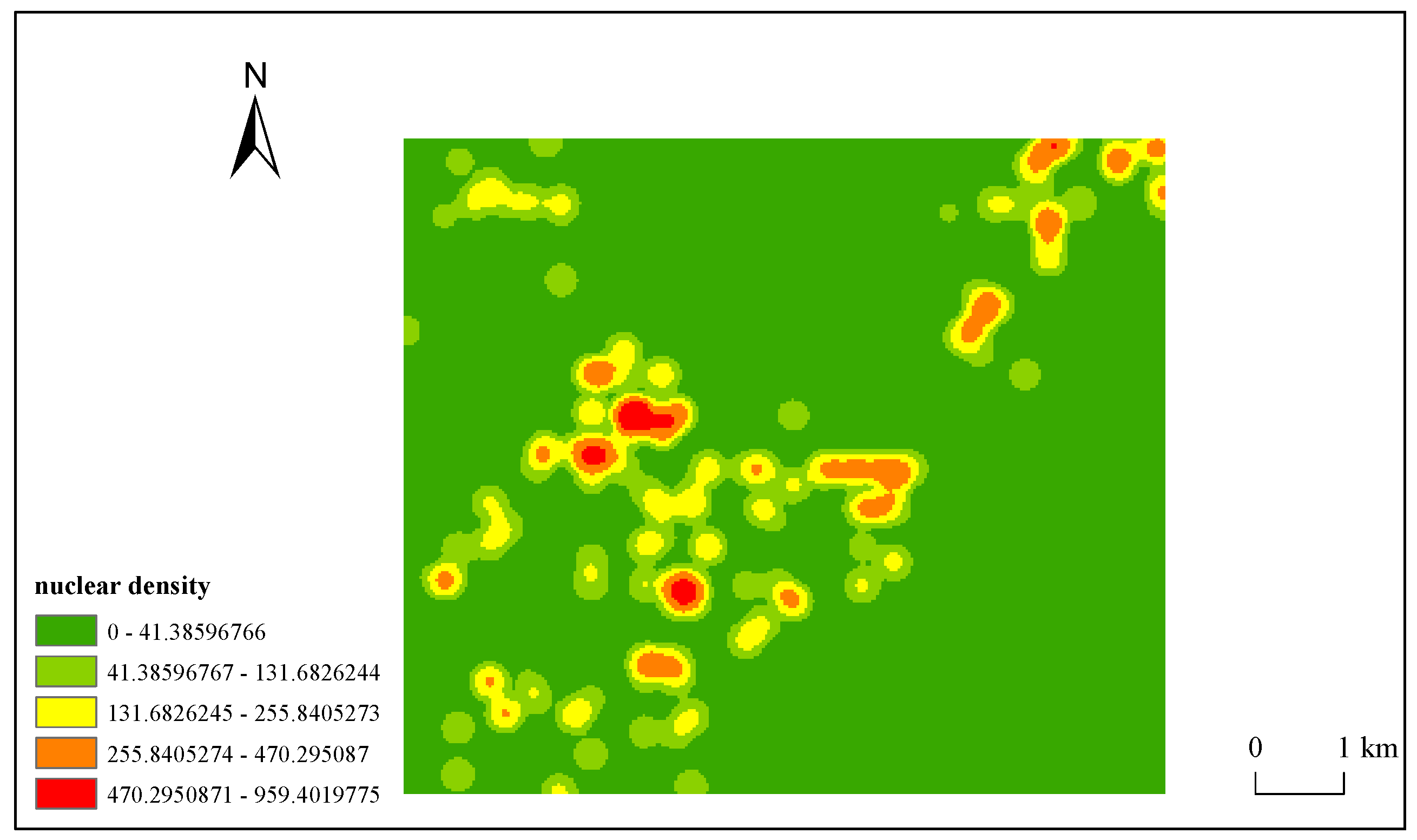

2.2.2. Baidu Heatmap Data

2.2.3. Amap POI Data

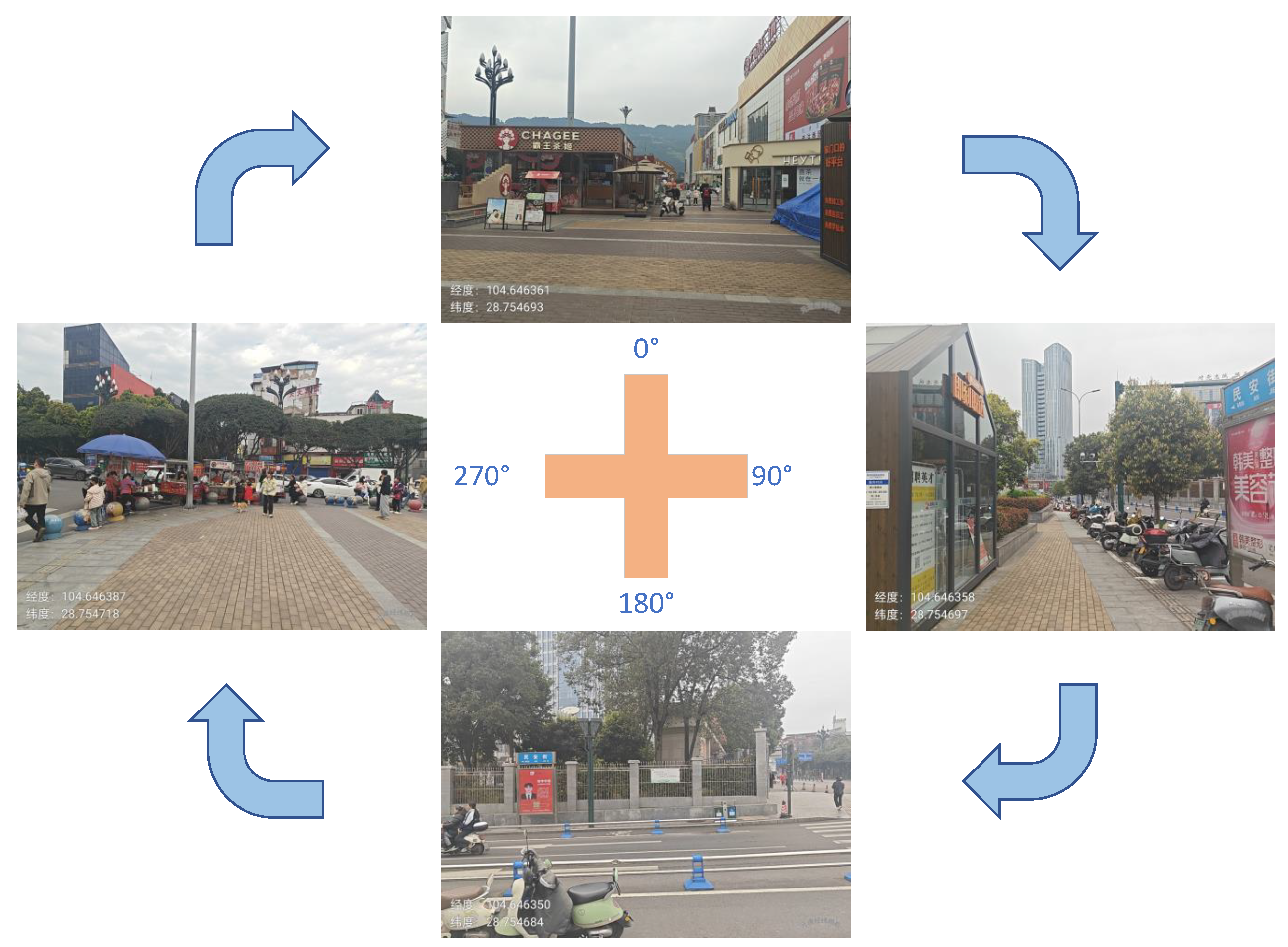

2.2.4. Street View Data

3. Methodology

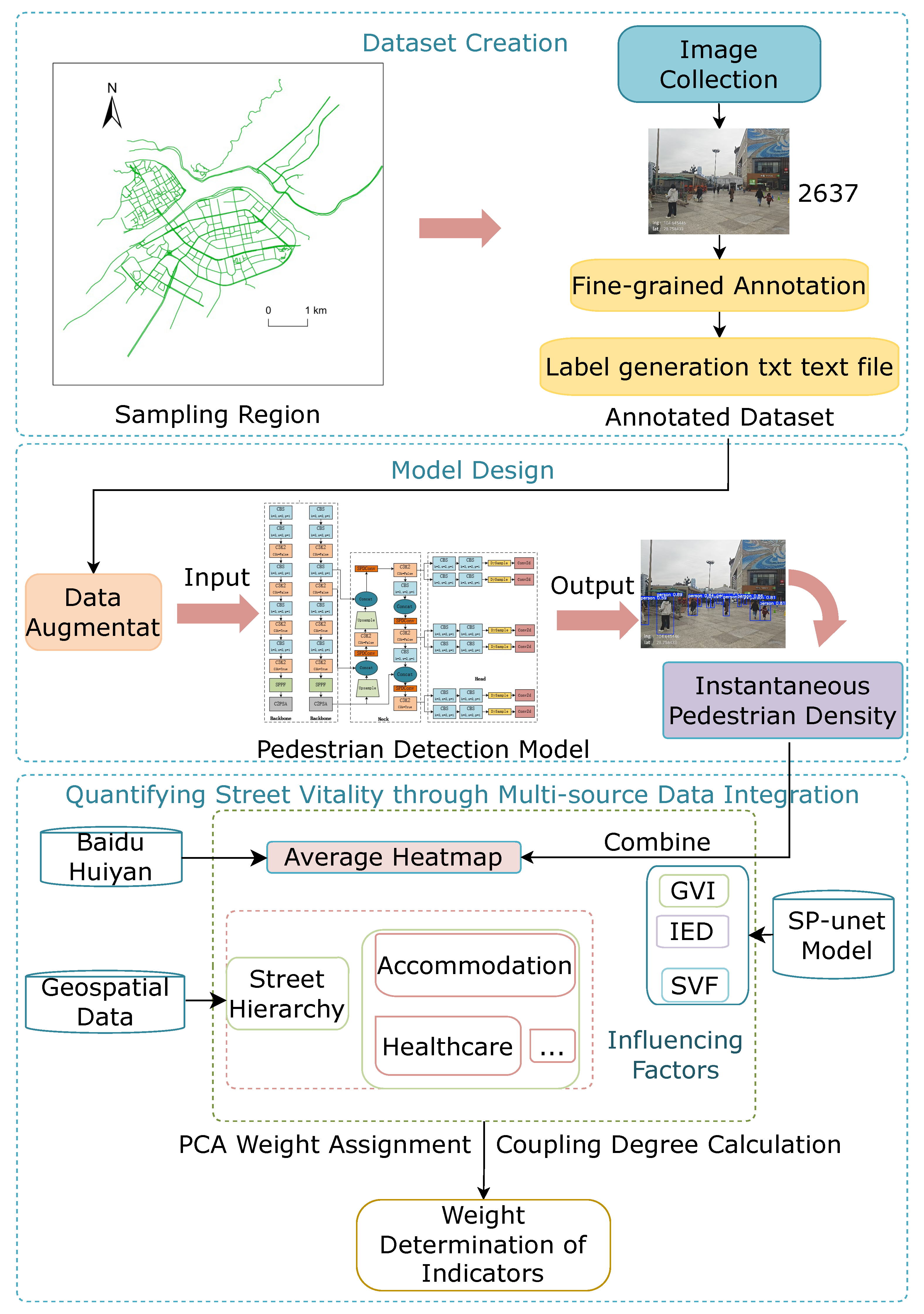

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Improved YOLOv11 Pedestrian Detection Model

- 1.

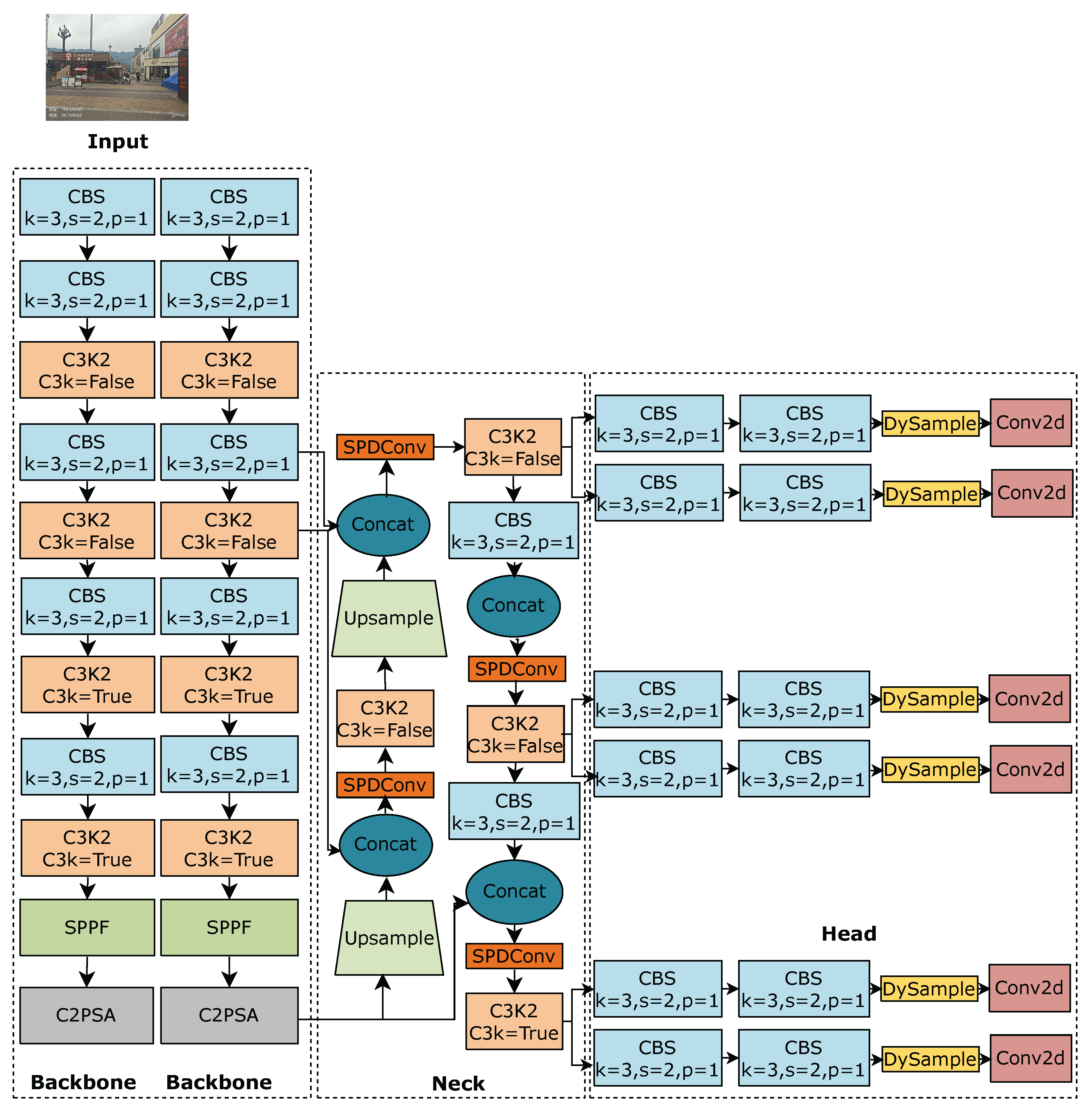

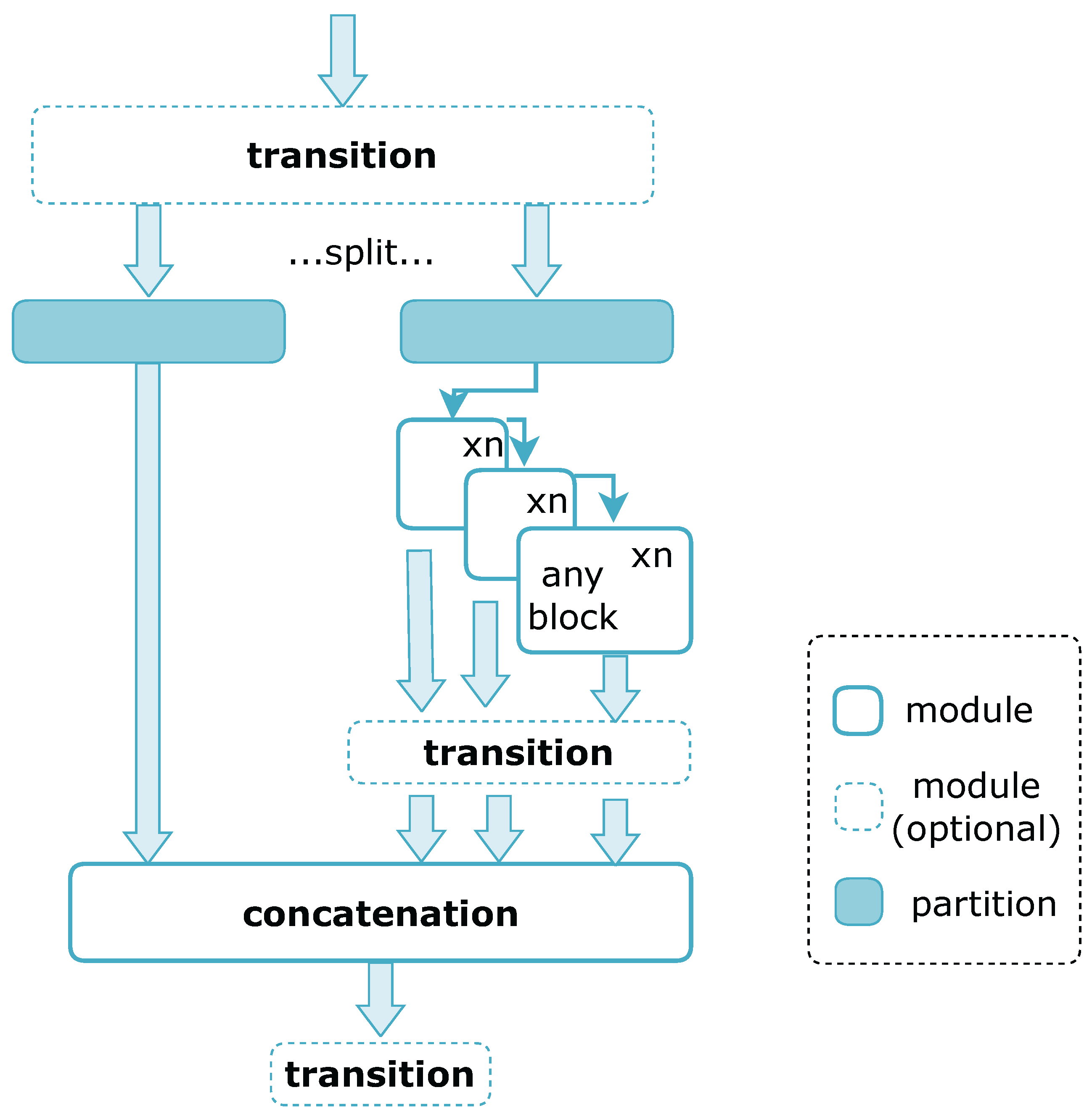

- To address the significant scale variation of pedestrians in street scenes, a Two-backbone architecture is proposed, as illustrated in Figure 6. The shallow branch employs a C3k2 module to capture fine-grained features such as pedestrian contours and poses, while the deep branch incorporates a CBFuse module to integrate multi-scale feature representations. Within this framework, the CBLinear module performs channel binding, and the CBFuse module utilizes nearest-neighbor interpolation for feature alignment and weighted fusion. The architecture retains two critical feature scales—1/8 and 1/16—ensures compatibility with pre-trained weights via a Silence module, and enhances feature representation through the incorporation of a C2PSA attention mechanism. This design preserves the computational efficiency of the original YOLOv11 while improving detection performance in occluded and high-density crowd scenarios through its dual-branch CBLinear–CBFuse structure. Experimental results demonstrate a 5.1% improvement in mAP50 compared to the single-backbone configuration.

- 2.

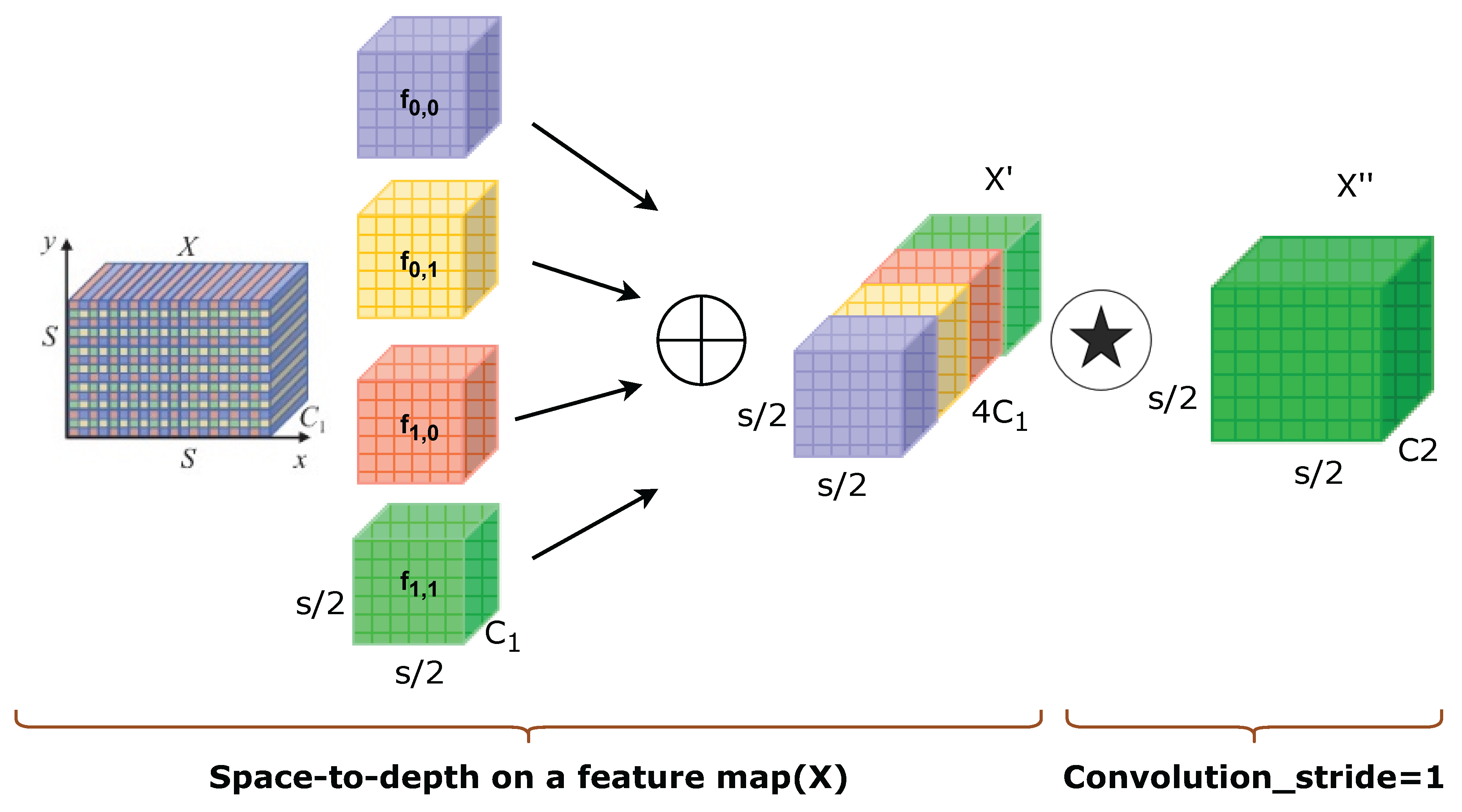

- To address the challenges of dynamic occlusion and complex backgrounds in street scene detection, this study incorporates a SPDConv module into the YOLOv11 architecture [29], as illustrated in Figure 7. This module employs spatial restructuring of feature maps to reduce resolution while preserving informational integrity, and utilizes parallel dilated convolutions with multiple dilation rates to capture multi-scale contextual features. By integrating a channel attention mechanism, it achieves adaptive fusion of local texture details and global semantic information. This design significantly enhances pedestrian detection accuracy in complex environments without compromising real-time performance, thereby offering a reliable quantitative evaluation tool for urban dynamic monitoring.

- 3.

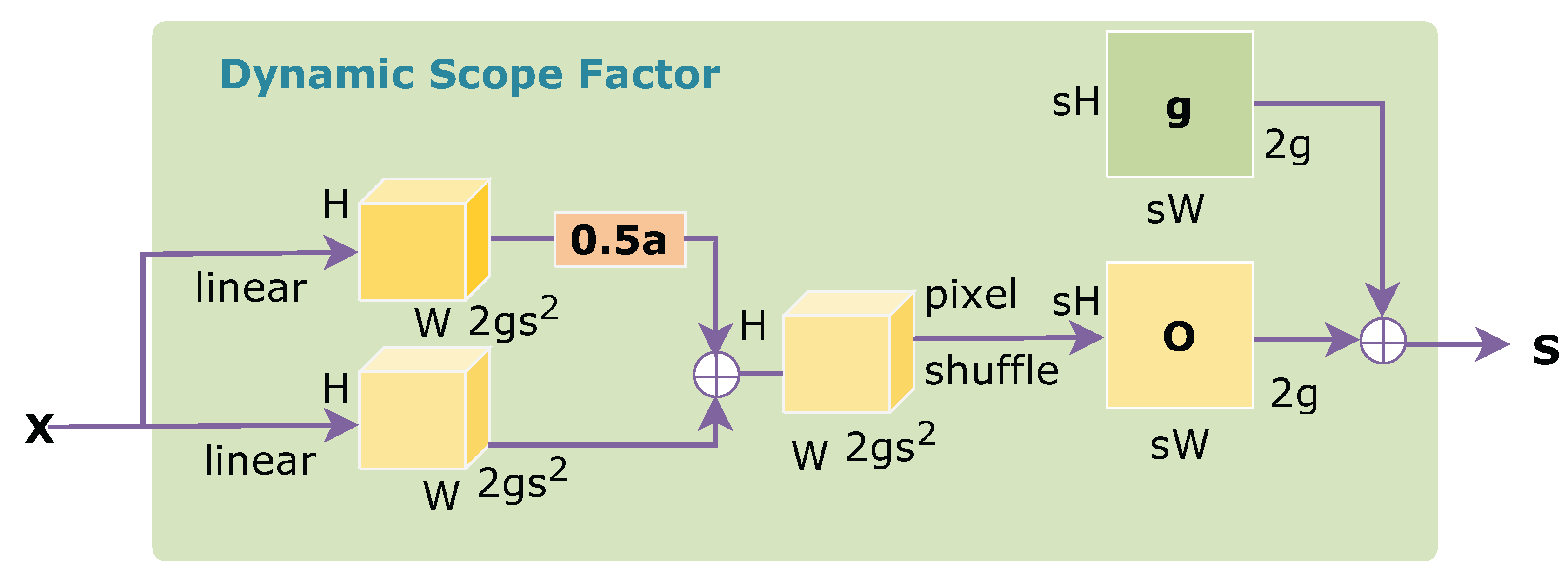

- To mitigate performance degradation in pedestrian detection caused by severe occlusion in high-density urban street scenarios, a DySample [30] is incorporated into the detection head of YOLOv11, as depicted in Figure 8. In contrast to conventional dynamic convolution methods (e.g., CARAFE, FADE), which rely on dynamic kernels to generate sub-networks, DySample operates through a point-based sampling strategy. Its core mechanism involves decomposing a single point in the input feature map into multiple sampling points. Initially, sampling positions are separated via bilinear initialization. Content-aware offsets are then generated to reconstruct the sampling grid, and standard bilinear interpolation is applied for feature resampling.The dynamic behavior arises from the input-dependent prediction of sampling offsets, eliminating the need for dynamic convolution kernels and requiring only a lightweight coordinate offset prediction module. Sparsity is achieved by locally constraining the offset range, which prevents boundary artifacts caused by overlapping sampling points and effectively mitigates feature loss due to motion blur and occlusion. This lightweight architecture offers a practical solution for continuous street vitality monitoring in complex urban environments.

3.3. Construction of a Built Environment Indicator System

-

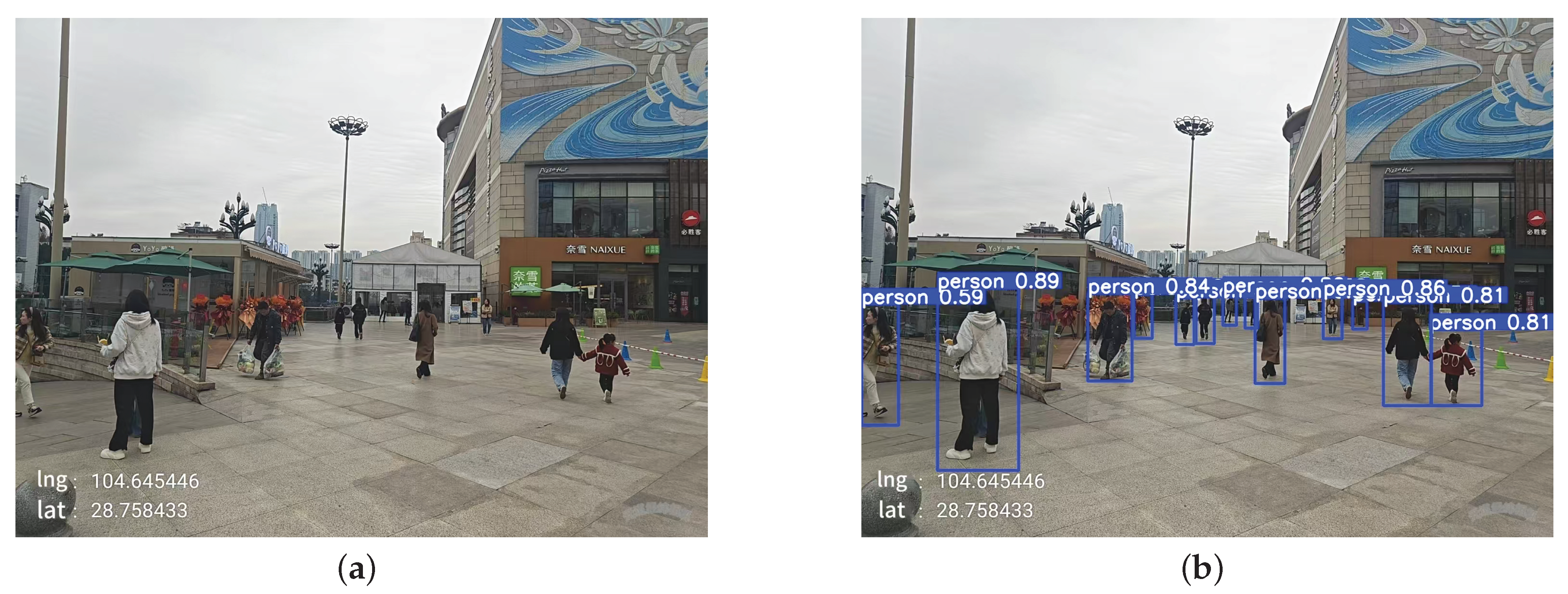

Quantification Method for External Representation of VitalityThe external representation of street vitality is quantified using the volume of crowd activities derived from location-based service data [31]. This study proposes two vitality measurement indicators: the average vitality intensity, which reflects the comprehensive vitality level throughout the day and is calculated as the mean of 24-hour heatmap data; and the instantaneous vitality intensity, which captures vitality characteristics at specific moments and is derived based on pedestrian detection results from street view images using an improved YOLOv11 model.

- 1.

- Instantaneous vitality intensity provides a dynamic characterization of street space vitality from the perspective of temporal slices. It refers to the relative density of people present in a street space at a given moment, denoted as Vi .

- 2.

-

The average vitality intensity represents the average level of street space vitality over a 24-hour period. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula, denotes the average vitality intensity value of the street; i represents different time intervals within a given day, where ; and n indicates the number of time intervals included in the calculation.

-

Quantification Method for Intrinsic Composition of Vitality

- 1.

-

Street HierarchyThis paper classifies roads into three tiers: arterial roads, secondary arterial roads, and branch roads, which are assigned values of 3, 2, and 1, respectively.

- 2.

-

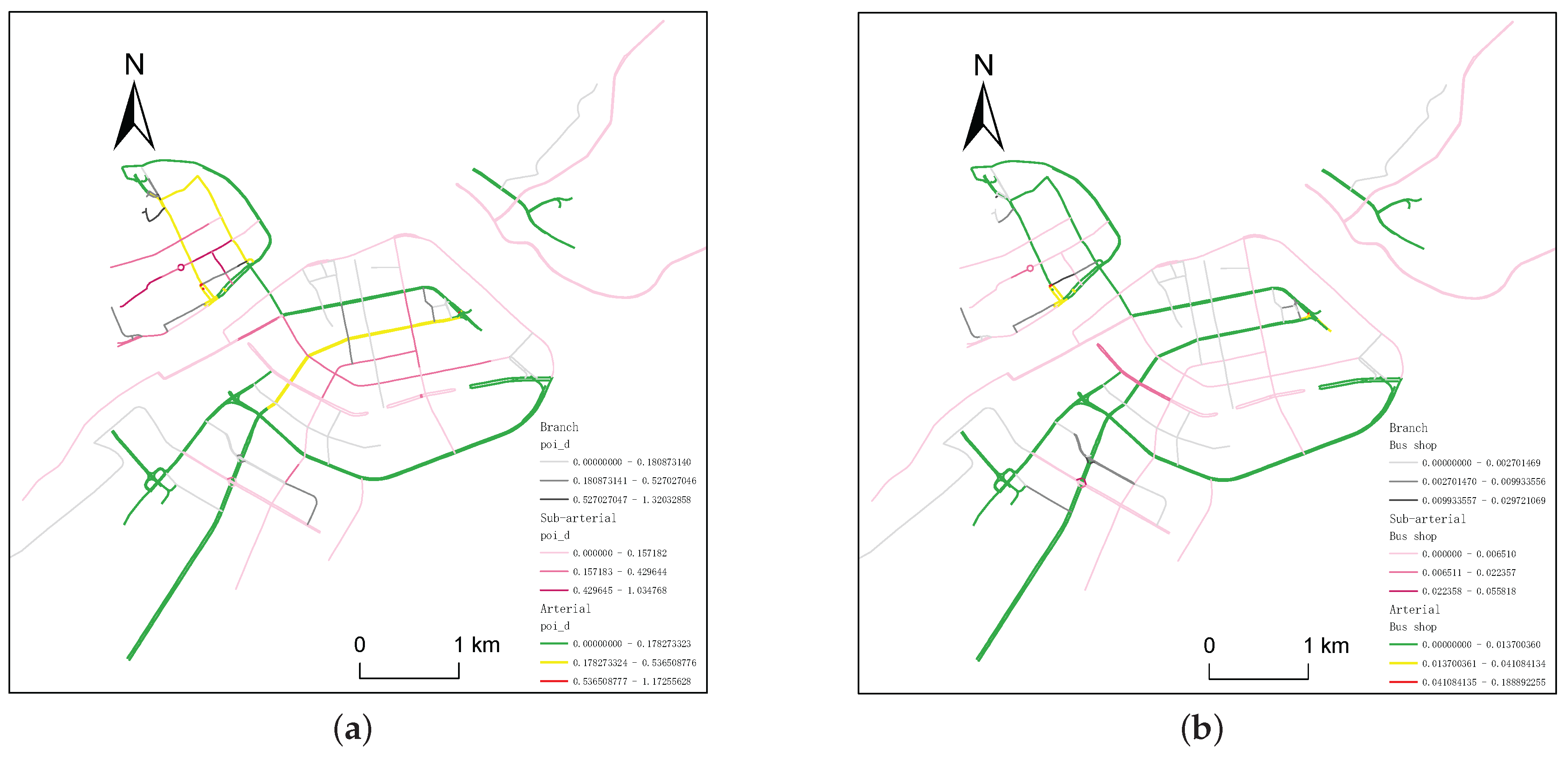

POI densityIt serves as an indicator of the concentration level of various functional types within a street. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula, denotes the public service facility density of the street, and represents the total number of catering, accommodation, health care, and shopping facilities within the street.

- 3.

-

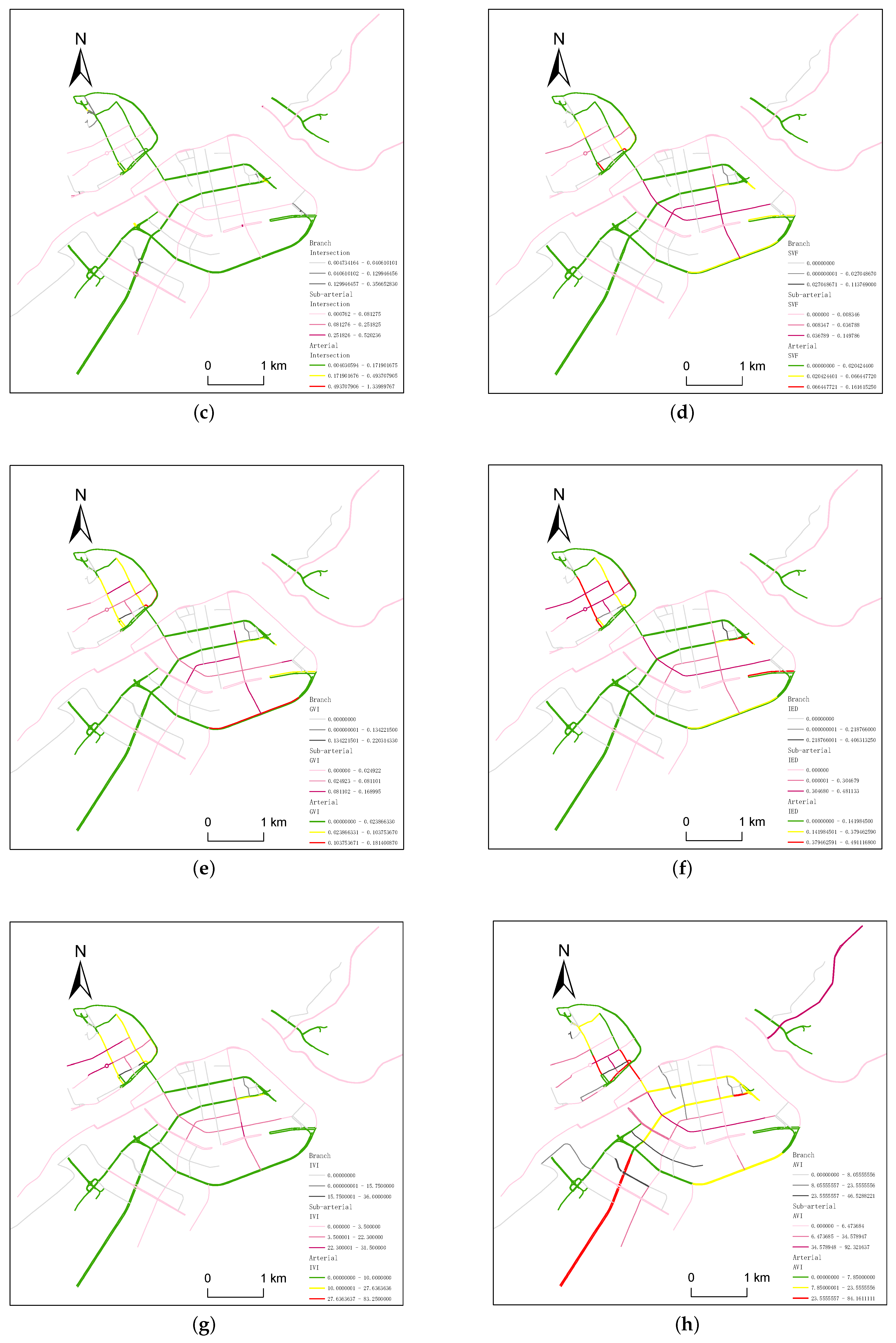

Intersection DensityIntersection density can, to some extent, reflect the density of the road network. It is quantified as the ratio of the number of intersections to the total length of road segments within the study area.

- 4.

-

Bus Stop DensityConvenient public transportation serves as a fundamental basis for organized vitality and contributes to its enhancement. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula, denotes the bus stop density of the street, and represents the total number of bus stops within the street.

- 5.

-

Green View IndexAdequate street greenery, such as providing shade and purifying the air, is considered instrumental in enhancing pedestrian comfort. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula, denotes the Green View Index of the street; represents the greenery area, and indicates the total area.

- 6.

-

Sky View FactorThe degree of openness or unobstructed space above a specific location or area. The proportion of sky in a pedestrian’s field of view can reduce feelings of psychological oppression. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula, denotes the Sky View Factor of the street, and represents the sky area.

- 7.

-

Spatial EnclosureIn any given street, the spatial enclosure is determined by the road width and building height. A higher degree of spatial enclosure indicates greater road width and higher building density on both sides. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula, denotes the spatial enclosure of the street, represents the building area, indicates the wall area, and refers to the fence area. Note: For specific calculation methods of the Green View Index, Sky View Factor, and Spatial Enclosure, see the authors’ other publication [32].

3.4. Standardization Framework for Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data and Spatio-temporal Coupling Modeling

-

Data Infrastructure Development and Standardized PreprocessingBased on the quantification methodologies established in Section 2.1, comprehensive data processing was executed: 13,150 POI across four categories—catering services, retail services, healthcare facilities, and accommodation—were acquired via API; 322 bus stops and 2,843 road intersections were extracted from geospatial datasets; street view imagery underwent semantic segmentation using the SP-Unet model to derive Green View Index, Sky View Factor, and Spatial Enclosure through pixel-level computation; instantaneous vitality intensity was quantified via pedestrian detection with the enhanced YOLOv11 framework; and average vitality intensity was calculated from Baidu Heatmap data obtained through the Baidu Huiyan platform. Data NormalizationIn the formula, denotes the raw value of the j -th indicator for the i -th street, while and represent the minimum and maximum values of each indicator, respectively, used to define the value range for normalization.Missing Value Handling: Outliers identified in the street view segmentation results were addressed using the median imputation method, thus maintaining data continuity.

-

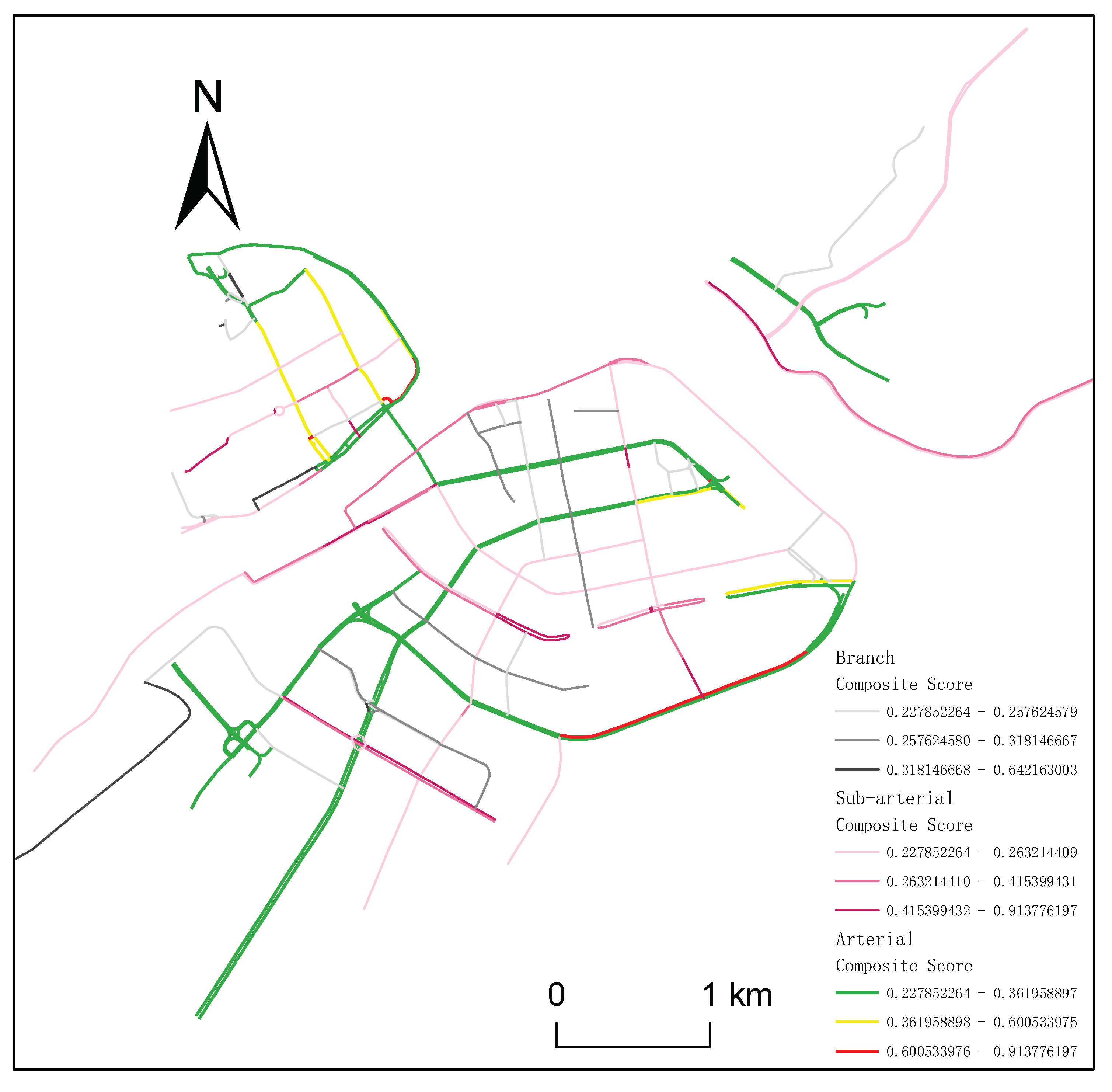

Three-Level Analytical Framework for Spatio-Temporal Coupling ModelsThree-tiered Analytical Framework for Spatio-temporal Coupling Modeling Standardization Layer [34]: As shown in Equation (7), the raw indicators are converted into comparable values within the [0,1] range.Academic Context:In the formula, denotes the weight of the j -th indicator in the k -th principal component, and represents the score of the k -th principal component.Academic Context:In the formula, denotes the principal component weight, and represents the deviation of the principal component score from its mean. T indicates the weighted composite score of the principal components, while C stands for the coordination index, quantifying the fluctuation equilibrium among elements within the system.A value of D>0.25suggests strong coupling, whereas D<0.15indicates a spatio-temporal mismatch. Detailed coupling analysis results are provided in Table 2.

| Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums | Rotation Sums | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Total | % Var. | Cum. % | Total | % Var. | Cum. % | Total | % Var. | Cum. % |

| 1 | 3.282 | 32.816 | 32.816 | 3.282 | 32.816 | 32.816 | 2.556 | 25.562 | 25.562 |

| 2 | 1.766 | 17.657 | 50.473 | 1.766 | 17.657 | 50.473 | 1.461 | 14.611 | 40.173 |

| 3 | 1.516 | 15.160 | 65.633 | 1.516 | 15.160 | 65.633 | 1.372 | 13.723 | 53.896 |

| 4 | 0.906 | 9.064 | 74.697 | 0.906 | 9.064 | 74.697 | 1.219 | 12.192 | 66.088 |

| 5 | 0.601 | 6.011 | 80.707 | 0.601 | 6.011 | 80.707 | 1.062 | 10.616 | 76.704 |

| 6 | 0.525 | 5.245 | 85.952 | 0.525 | 5.245 | 85.952 | 0.925 | 9.248 | 85.952 |

| 7 | 0.499 | 4.990 | 90.943 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | 0.400 | 4.003 | 94.945 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | 0.296 | 2.959 | 97.904 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | 0.210 | 2.096 | 100.000 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Model Performance Evaluation

4.1.1. Ablation Experiment

| Model | Precision (P) | Recall (R) | mAP50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 | 83.9 | 62.0 | 72.1 |

| YOLOv11 + Two-backbone | 86.9 | 66.9 | 76.2 |

| YOLOv11 + SPDConv | 86.3 | 65.6 | 74.8 |

| YOLOv11 + DySample | 87.3 | 63.8 | 74.4 |

| YOLOv11 + Two-backbone + SPDConv | 88.5 | 67.1 | 76.3 |

| YOLOv11 + Two-backbone + SPDConv + DySample | 90.4 | 67.3 | 77.2 |

4.1.2. Comparative Experiment

4.2. Spatial Distribution of Street Vitality

4.3. Results of the Spatio-temporal Coupling Model

5. Conclusions

- 1.

-

Data Acquisition and PreprocessingGeoreferenced sampling points were derived from Yibin’s road network data, with street view imagery collected through field surveys. Image preprocessing involved noise reduction, outlier handling, and missing-value imputation to enhance data quality. A customized dataset was constructed using Labelme for manual annotation, supplemented by public datasets for joint training. Integration of Baidu heatmaps and Amap POI data established a comprehensive vitality analysis database.

- 2.

-

Model Architecture and PerformanceThe enhanced YOLOv11 architecture incorporates three innovative technological breakthroughs: Two-backbone feature extraction networks, spatial pyramid depth-wise convolution (SPDConv), and dynamic sparse sampling (DySample). Experimental validation demonstrates significant performance gains: 6.5%↑ precision, 5.3%↑ recall in occlusion scenarios, and 5.1%↑ mAP@50 versus baseline models. The model outperforms state-of-the-art detection algorithms across all critical metrics, establishing robust capabilities for high-density urban environments.

- 3.

-

Spatio-temporal Coupling MechanismA vitality-built environment coupling model was developed, integrating temporal dimensions (instantaneous/average vitality intensity) and spatial indicators (POI density, street hierarchy, bus stop density, intersection frequency, Green View Index, Sky View Factor, and interface enclosure). Principal component analysis revealed intrinsic weight relationships among these dimensions, enabling computation of composite vitality scores for each street.

- Urban administrators should implement a multi-dimensional intervention strategy encompassing spatial optimization through pedestrian node integration in low-coupling zones—particularly high-density public service areas—to enhance vitality permeability and walkability via street layout refinements; traffic management via dynamic lane allocation deployed through Intelligent Transportation Systems during peak hours on vitality-overflow corridors, improving traffic efficiency while mitigating congestion impacts; environmental enhancement through increased green infrastructure coverage and Sky View Factor elevation to improve microclimate quality, resident comfort, and aesthetic value; and facility optimization via commercial hub development with balanced public service distribution, transit network optimization, and smart urban management system implementation, collectively improving facility accessibility and citizen-centric service delivery to enhance quality of life. This integrated approach addresses spatial, mobility, ecological, and infrastructural dimensions to holistically activate urban vitality.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, D.; Tian, J.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, J.; Namaiti, A. Identification and Spatiotemporal Evolution Analysis of the Urban–Rural Fringe in Polycentric Cities Based on K-Means Clustering and Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Chengdu City. Land 2024, 13, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, Q.; Run, Y.; Han, Z. Multidimensional urban vitality on streets: Spatial patterns and influence factor identification using multisource urban data. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ge, J.; He, W. Quantifying Urban Vitality in Guangzhou Through Multi-Source Data: A Comprehensive Analysis of Land Use Change, Streetscape Elements, POI Distribution, and Smartphone-GPS Data. Land 2025, 14, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.J.; Kim, Y.j. Planning paradigm shift in the era of transition from urban development to management: The case of Korea. In Urban Planning Education: Beginnings, Global Movement and Future Prospects; Springer, 2017; pp. 161–174.

- Al-Thani, S.K.; Amato, A.; Koç, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Urban sustainability and livability: An analysis of Doha’s urban-form and possible mitigation strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Li, L.; Nian, M. China’s urbanization strategy and policy during the 14th five-year plan period. Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies 2021, 9, 2150002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Liu, A. Evaluation and Optimization of Urban Street Spatial Quality Based on Street View Images and Machine Learning: A Case Study of the Jinan Old City. Buildings 2025, 15, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Gao, B.; Wang, S.; Qi, Y.; Zou, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, R. A study on identifying the spatial characteristic factors of traditional streets based on visitor perception: Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province. Buildings 2024, 14, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pang, C. A Spatial Visual Quality Evaluation Method for an Urban Commercial Pedestrian Street Based on Streetscape Images—Taking Tianjin Binjiang Road as an Example. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milias, V.; Sharifi Noorian, S.; Bozzon, A.; Psyllidis, A. Is it safe to be attractive? disentangling the influence of streetscape features on the perceived safety and attractiveness of city streets. AGILE: GIScience Series 2023, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Long, Y. Characterizing and Measuring the Environmental Amenities of Urban Recreation Leisure Regions Based on Image and Text Fusion Perception: A Case Study of Nanjing, China. Land 2023, 12, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z. Evaluating Urban Visual Attractiveness Perception Using Multimodal Large Language Model and Street View Images. Buildings 2025, 15, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, A.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, S. Spatial characteristics of multidimensional urban vitality and its impact mechanisms by the built environment. Land 2024, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kozlowski, M.; Salih, S.A.; Ismail, S.B. Evaluating the vitality of urban public spaces: perspectives on crowd activity and built environment. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2024.

- Liu, W.; Yang, Z.; Gui, C.; Li, G.; Xu, H. Investigating the Nonlinear Relationship Between the Built Environment and Urban Vitality Based on Multi-Source Data and Interpretable Machine Learning. Buildings 2025, 15, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Z. Integrating multi-source urban data with interpretable machine learning for uncovering the multidimensional drivers of urban vitality. Land 2024, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Ding, L.; Zheng, J. A Multi-Dimensional Evaluation of Street Vitality in a Historic Neighborhood Using Multi-Source Geo-Data: A Case Study of Shuitingmen, Quzhou. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2025, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, X. An evaluation of street dynamic vitality and its influential factors based on multi-source big data. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2021, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y. Spatial explicit assessment of urban vitality using multi-source data: A case of Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhang, A.; Yeh, A.G. The varying relationships between multidimensional urban form and urban vitality in Chinese megacities: Insights from a comparative analysis. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 2022, 112, 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zarin, S.Z.; Niroomand, M.; Heidari, A.A. Physical and social aspects of vitality case study: Traditional street and modern street in Tehran. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 170, 659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Niu, X. Influence of built environment on urban vitality: Case study of Shanghai using mobile phone location data. Journal of Urban Planning and Development 2019, 145, 04019007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Niu, X.; Li, M. Influence of built environment on street vitality: A case study of West Nanjing Road in Shanghai based on mobile location data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangbao, L. Spatial impact of the built environment on street vitality: A case study of the Tianhe District, Guangzhou. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 966562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S. Influencing factors of street vitality in historic districts based on multisource data: evidence from China. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yabuki, N.; Fukuda, T. Exploring the association between street built environment and street vitality using deep learning methods. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 79, 103656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, X.; Tan, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, S.; You, W. Analysis of Spatial Vitality Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Old Neighborhoods: A Case Study of Ya’an Xicheng Neighborhood. Buildings 2024, 14, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.17725 2024.

- Yang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y. A new semantic segmentation method for remote sensing images integrating coordinate attention and SPD-Conv. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Qu, D.; Du, L. DDM-YOLOv8s for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing (MLNLP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–7.

- Zhou, Q.; Zheng, Y. Evaluation research on the spatial vitality of Huaihe Road commercial block in Hefei city based on multi-source data correlation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Lv, W. Optimizing Semantic Segmentation of Street Views with SP-UNet for Comprehensive Street Quality Evaluation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, G. Revealing the spatio-temporal heterogeneity of the association between the built environment and urban vitality in Shenzhen. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2023, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, J. Predicting urban vitality at regional scales: A deep learning approach to modelling population density and pedestrian flows. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Song, Z. YOLO sparse training and model pruning for street view house numbers recognition. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2023, Vol. 2646, p. 012025.

- Yang, J.; Li, X.; Du, J.; Cheng, C. Exploring the relationship between urban street spatial patterns and street vitality: A case study of Guiyang, China. International journal of environmental research and public health 2023, 20, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Transportation | Accommodation | Catering | Shopping | Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 676 | 1,170 | 10,631 | 23,534 | 3,547 |

| Fid | Composite Score |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.263214 |

| 1 | 0.230591 |

| 2 | 0.234090 |

| 3 | 0.252188 |

| 4 | 0.231865 |

| 5 | 0.294571 |

| Model | Precision (P) | Recall (R) | mAP50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 | 83.9 | 62.0 | 72.1 |

| YOLOv8 | 82.8 | 64.0 | 71.7 |

| YOLOv6 | 81.7 | 60.0 | 70.3 |

| YOLO10n | 82.1 | 61.3 | 71.5 |

| YOLOv3-tiny | 81.0 | 59.9 | 66.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).