1. Introduction

A novel coronavirus outbreak began in China at the end of 2019, leading to a global pandemic by March 2020, as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO). This disease, named COVID-19, is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [

1]. Coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, are enveloped, positive single-strand RNA viruses from the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily, characterized by their “crown-like” spikes [

2]. SARS-CoV-2 is a zoonotic virus with a low to moderate mortality rate [

2,

3]. COVID-19 has a mean incubation period of 5.2 days [

4]. Symptoms usually begin with nonspecific signs, including fever, dry cough, and fatigue. Multiple systems may be involved, including the respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and neurologic systems. The most common signs and symptoms are fever, cough, and shortness of breath [

5,

6]. After the onset of illness, symptoms are generally mild, with a median time to first hospital admission of 7 days [

5]. Patients with fatal disease develop acute respiratory distress syndrome, which worsens rapidly, leading to multiple organ failure [

5,

6].

The virus primarily infects cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is abundantly expressed in type II alveolar cells of the lung, making these cells the main viral target [

7,

8]. However, significant viral replication occurs in the upper respiratory tract, with high pharyngeal shedding observed during the initial week of symptoms [

9]. The nasopharynx has a higher viral load compared to the oropharynx, indicating that transmission can occur through both saliva and nasal secretions [

10]. Thus, targeting the upper respiratory tract could be crucial in slowing disease progression and reducing transmission.

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of various nasal and mouth products in COVID-19 management. A nasal spray containing 0.005% hypochlorous acid demonstrated significant virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2 in mild COVID-19 patients [

11], while a 0.23% povidone-iodine nasal rinse and mouthwash regimen significantly reduced viral load and the infectious period, although it did not significantly impact quality-of-life measures in recently vaccinated or mild cases [

12]. Povidone-iodine was found to be more effective than chlorhexidine in reducing SARS-CoV-2 salivary viral load [

13], and mouthwashes with 0.07% cetylpyridinium chloride effectively inactivated SARS-CoV-2 in saliva, suggesting their potential to reduce viral load and transmission [

14]. Cetylpyridinium chloride has also been shown to inhibit the interaction between the viral spike protein and ACE2, reducing SARS-CoV-2 infectivity [

15]. Despite these promising results, further validation in larger studies is needed to confirm these findings.

Natural products, particularly medicinal plant extracts, offer a promising alternative to conventional anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs due to their safety, affordability, and availability [

16]. D-limonene, a key component of orange and lemon essential oils, has shown potential in anti-SARS-CoV-2 applications. It inhibits the viral genome without exhibiting mutagenic or cytotoxic effects and possesses favorable pharmacokinetics [

17]. Due to its structure, which is similar to thymidine, D-limonene has an enhanced affinity for viral components and interferes with the PI3K/Akt/IKK-α/NF-κB p65 signaling pathway, potentially reducing the risk of COVID-19-related pulmonary fibrosis [

18]. As a natural monoterpene, limonene is known for its rapid absorption and high bioavailability in mucosal tissues, such as the oral and nasal cavities. These properties allow it to maintain effective concentrations at viral entry sites, potentially boosting its antiviral activity. Additionally, limonene has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, which could help alleviate symptoms in patients with COVID-19 [

19,

20,

21].

Monolaurin, a monoglyceride found in coconut oil, is FDA-recognized as safe and demonstrates potent antiviral and antibacterial activity [

22]. It disrupts viral envelopes and enhances immune function by modulating cytokine responses and attracting leukocytes [

23,

24]. Monolaurin shows promise as a dietary supplement for boosting immunity and combating viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2 [

25,

26]. This review explores monolaurin’s properties and its potential as a COVID-19 treatment alternative.

Lately, the use of a portable inhaler device for inhalation treatment has been proposed for COVID-19 due to its ease of use and accessibility. This method could facilitate early antiviral administration, helping to prevent the progression and spread of the virus. Since SARS-CoV-2 transmits via airborne particles, the ciliated nasopharyngeal epithelium and oral cavity are identified as primary sites of infection [

27,

28]. Research indicates that the ACE2 receptor is more abundantly expressed in the nasal cavity than in peripheral lung tissue [

28], suggesting that the nasal cavity is the principal entry point for the virus into the human body [

29,

30]. In a meta-analysis examining the virucidal efficacy of various preparations against SARS-CoV-2 in vivo, aggregated data indicated that the use of a mouth rinse or nasal spray significantly decreased the salivary viral load [

16].

The aim of this study was to conduct a clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of two distinct formulations for the treatment of COVID-19. The nasal formulation, designed for spray application, contained D-limonene and cetylpyridinium chloride. The oral formulation, intended for use as both a mouth spray and a mouthwash, incorporated D-limonene, monolaurin, and cetylpyridinium chloride. The trial assessed the concurrent use of these formulations as a nasal spray, mouth spray, and mouthwash in COVID-19 patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (RCT) was conducted at Dontum Hospital in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, between May 17 and November 5, 2022. The study protocol was initially revised according to the committee’s comments before the research commenced, and no further amendments were made during the course of the study. The trial adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and followed Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. Reporting of the study followed the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement [

31]. The study registration was completed under project code REC 65.0323-053-2479 with a certification date of May 17, 2022, and an expiry date of May 16, 2023. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Human Subjects under the Silpakorn University Research, Innovation, and Creativity Administration Office, Thailand (approval number: COE 65.0517-081, effective from May 17, 2022, to May 16, 2023). The study was registered in the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) with the trial registration ID TCTR20240803002, approved on August 3, 2024. Detailed information about the trial design, participants, interventions, and outcomes is provided in accordance with these guidelines.

2.2. Participants

Identification of potentially eligible participants was conducted by screening requests for molecular diagnostics of SARS-CoV-2, which were processed at the regional reference laboratory for COVID-19 diagnostics. Eligibility was confirmed through positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) results obtained from Dontum Hospital (Nakhon Pathom, Thailand). Specifically, the study focused on individuals aged 18 years or older who reside in the municipality of Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, and who are not pregnant (in the case of females). Potentially eligible participants underwent initial pre-screening at Dontum Hospital by research staff, who inquired about symptoms of the disease. Those who expressed willingness to participate received treatment at the hospital under the care of specialist doctors.

For enrollment in the study, subjects were required to present with asymptomatic or mild-to-moderate clinical illness, exhibiting at least one COVID-19-attributable symptom (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, nasal congestion, parosmia) emerging less than 3 days prior to potential enrollment. The severity of disease was defined according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [

32]. Principal exclusion criteria included treatment with medications known or presumed to have antiviral activity, significant co-morbidities, hypersensitivity to any ingredients in the developed anti-SARS-CoV-2 nasal and mouth formulations, cognitive impairment, use of high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive ventilation, alcohol or substance misuse, confirmed pregnancy, lactation, or recent or prior participation in other clinical investigations.

2.3. Interventions

The nasal formulation contained D-limonene (0.2% w/w) and cetylpyridinium chloride (0.05% w/w), while the mouth formulation consisted of D-limonene (0.3% w/w), monolaurin (0.2% w/w), and cetylpyridinium chloride (0.05% w/w), all incorporated in a homogenized liquid carrier. Monolaurin was included exclusively in the oral formulation, as there are no documented reports of its use in nasal applications. The nasal formulation demonstrated a 2.9063 ± 0.1197 log reduction and 99.87 ± 0.0369% efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 within 120 s, while the mouth formulation exhibited a 3.875 ± 0.1021 log reduction and 99.99 ± 0.0032% efficacy within the same time frame [

33]. Both formulations complied with safety standards for heavy metal content and microbial contamination. They were prepared by pharmacists at Dontum Hospital, following established protocols from previous studies [

34,

35]. Owing to their safe composition, no special handling was required.

The nasal formulation, delivered in a 15-ml amber glass bottle with a nasal spray head, was used to reduce SARS-CoV-2 nasal viral load. Each dose involved applying 0.26 ml into each nostril three times daily, with instructions to clear mucus first, spray twice while inhaling, and avoid nose blowing for 15 min.

The mouth formulations were provided in two packaging formats: a 240-ml polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle for the mouthwash and a 15-ml amber glass bottle with a spray head for the mouth spray. These formulations were used to hydrate the oral cavity and reduce viral load. For the mouthwash, 10 ml was gargled twice daily, once in the morning after brushing and again before bedtime. For the mouth spray, 0.33 ml was applied directly to the mouth and throat three times a day.

Both patients and caregivers were blinded to the intervention in this double-blind trial. Patients received packets containing nasal spray, mouth spray, and mouthwash, which either included the active ingredients or a placebo (without active ingredients), and remained hospitalized throughout the study.

In terms of safety and stability, D-limonene is classified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), indicating its relative safety for use [

36]. Monolaurin is also classified as GRAS for human consumption and can be used as a food additive [

37]. Due to its broad-spectrum antiviral activity and favorable safety profile, monolaurin is being explored for incorporation into various antiviral formulations. Cetylpyridinium chloride is similarly designated as GRAS and is commonly used as an active ingredient in mouthwashes and lozenges to reduce viral load [

38]. In research and formulation contexts, cetylpyridinium chloride, D-limonene, and monolaurin are often utilized at concentrations ranging from 0.05% to 0.075% w/w, 0.2% to 0.3% w/w, and 0.1% to 0.2% w/w, respectively [

39,

40,

41]. These concentrations are selected to achieve a balance between efficacy and safety. For specific applications, such as nasal sprays, mouth sprays, or mouthwashes, these ranges are considered effective in providing antiviral activity while minimizing the potential for irritation. The shelf life of the formulations was determined through stability testing conducted at 25 °C ± 2°C and 75% ± 5% relative humidity. These tests confirmed that the products remained stable for at least 12 months, ensuring their consistency throughout the study period.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary endpoint was to evaluate the efficacy of the investigational products in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms at any point during the treatment period (days 1 to 7), as determined through patient self-assessments. Secondary endpoints included comparing the duration of symptom improvement or complete resolution between the experimental and control groups. Additional secondary outcomes were the frequency of adverse events (AEs) and patient satisfaction, which was measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

2.5. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated to detect a clinically meaningful difference in symptom reduction between the experimental and control groups, assuming an effect size of 20%, based on expert opinion and similar interventions for respiratory conditions. This effect size was considered clinically significant for the management of common COVID-19 symptoms (e.g., fever, sore throat, cough, and nasal congestion). To achieve 80% statistical power at a two-sided significance level (α) of 0.05, the standard deviation (σ) was set at 0.5 [

42]. The sample size for comparing two independent means was determined using the following formula (Equation (1)):

where:

Zα/2 = 1.96 (for a two-sided significance level of 0.05)

Zβ = 0.84 (for 80% power)

Δ = 0.2 (effect size)

σ = 0.5 (standard deviation)

Using these values, the minimum required sample size was 49 participants per group, which was rounded up to 50. To account for a potential 30% dropout rate, the target enrollment was increased to 65 participants per group, resulting in a total of 130 participants for the trial. Ultimately, data were successfully collected from 120 participants—61 in the experimental group and 59 in the control group. Despite being slightly below the target, both groups exceeded the minimum required sample size, thereby maintaining the study’s intended statistical power and ensuring the robustness of the findings.

2.6. Randomization and Blinding

Patients who met all inclusion and exclusion criteria were informed about the study, and informed consent was obtained from those willing to participate. Upon enrollment, each patient was assigned a sequential serial number based on the order in which they enrolled. Randomization was then performed using these serial numbers to allocate patients to one of the trial groups. The pharmacist played a critical role in maintaining the double-blind design, ensuring that neither the outcome assessors nor the patients were aware of group assignments.

2.7. Study Procedures

On day 0, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria and obtaining informed consent, eligible participants were attended to in the isolation room. A qualified physician collected relevant medical history, current medications, and COVID-19-related symptoms, conducted a physical examination, and recorded primary vital signs, including body temperature, heart rate, and oxygen saturation (measured with a fingertip pulse oximeter).

To ensure compliance with GCP guidelines, the study implemented rigorous monitoring and oversight procedures. Clinical monitoring was conducted by a designated monitor who made regular visits to verify protocol adherence and ensure data integrity. Additionally, an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed safety data and monitored AEs throughout the study.

All randomized participants received standard care, tailored to their age and medical history, with a focus on supportive measures for asymptomatic and mild-to-moderate COVID-19 cases [

43]. Adequate hydration and rest were provided, with identical meals served at each mealtime to ensure consistency. Participants were closely monitored for signs of complications, such as increased shortness of breath or chest pain, which could indicate disease progression.

2.8. Data Collection and Compliance

An online Google Form questionnaire, accessible via QR code scan, was provided along with instructions for its completion. The questionnaire included inquiries about the severity of symptoms (such as sore throat, cough, mucus, runny nose, nasal congestion, fever, and headache) and any AEs experienced after administering the antiviral products. Patients rated their overall satisfaction with the severity levels of symptoms after using the virucidal products on a 7-point Likert scale, which included the options: worse, as before, slightly better, moderately improved, much better, completely recovered, and no previous symptoms. Patients completed the online Google Form questionnaire on three separate days: days 1, 3, and 7. AEs and vital signs were assessed at each visit. To ensure treatment compliance, from days 1 to 7, the research staff reviewed the use of the products with each participant before each scheduled spray administration. After completing the treatment on day 7, the remainder of the investigational product was retrieved. On the same day, following a physical examination, all participants were asked to rate the overall tolerability and sensory satisfaction with the investigational products. This assessment was conducted using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from very unsatisfied to very satisfied [

44].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages. Qualitative variables were presented as counts and analyzed using chi-square tests. Statistical significance was defined as p-values less than 0.05. For quantitative variables, independent z-tests were applied. Additionally, a t-test was utilized to compare patient satisfaction with antiviral products. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 23).

3. Results

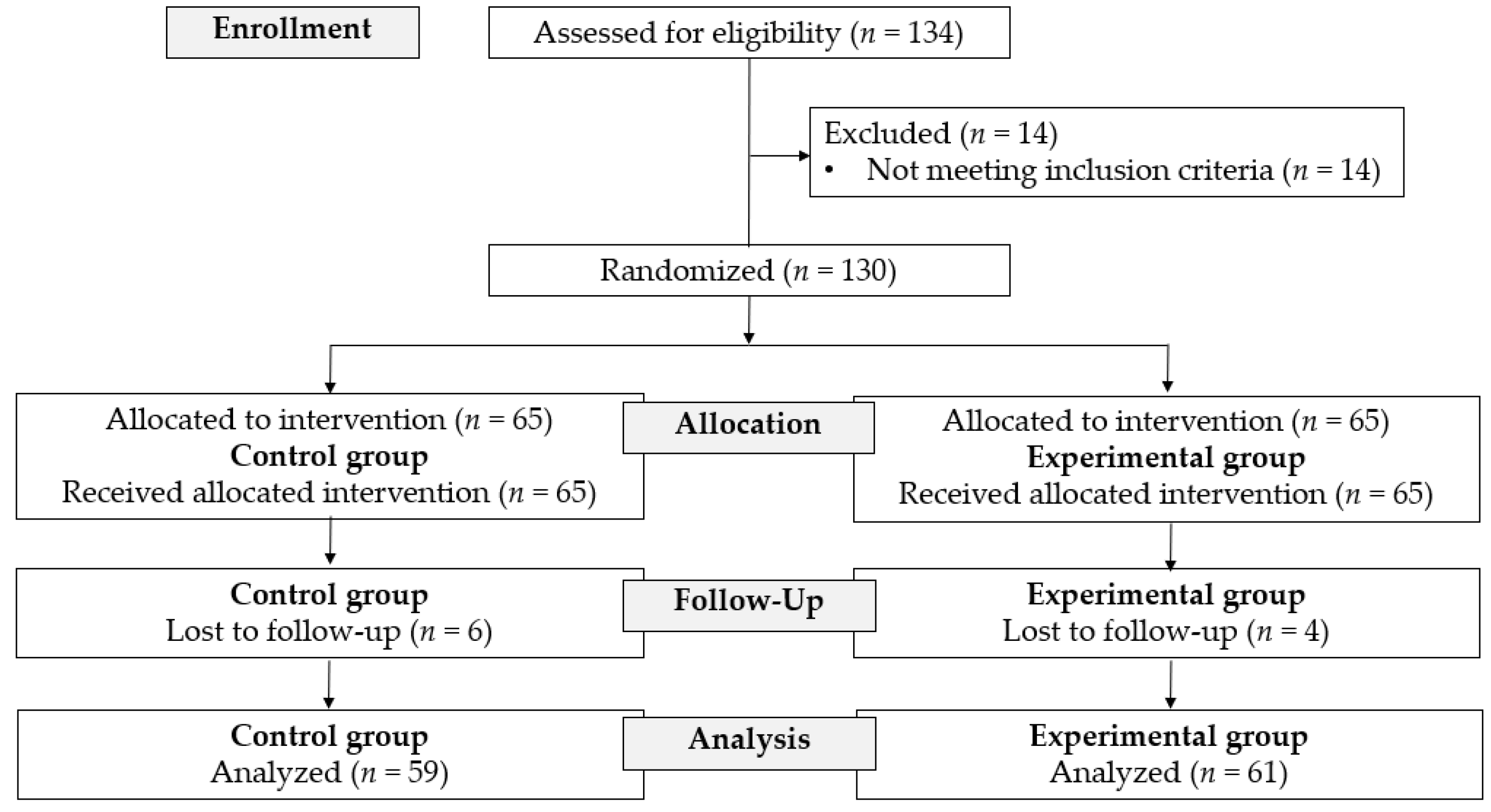

Between May 17 and November 5, 2022, 134 patients were assessed for eligibility. Fourteen patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. A total of 130 patients were enrolled in the study and were randomized equally into either the experimental or control group. Of these 130 patients, 10 were lost to follow-up (four in the experimental group and six in the control group). Therefore, the observations reported in this study are based on 120 patients, divided into the experimental group (

n=61) and the control group (

n=59) (

Figure 1).

Reflecting the clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection as outlined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the symptomatic presentation of COVID-19 can vary significantly among individuals. Symptoms range from asymptomatic or mild (green category) to moderate (yellow category), severe, or critical illness (red category) [

45]. This study focused on patients categorized in the yellow category. Patients in this group exhibited moderate symptoms, including fatigue, chest tightness, difficulty breathing, rapid breathing, cough, tiredness when coughing, dizziness, vomiting, pneumonia, and diarrhea occurring at least three times per day. Additionally, complications related to risk factors or underlying conditions were present, such as being over 60 years of age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung diseases, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, stroke, uncontrolled diabetes, obesity (weighing more than 90 kg), liver cirrhosis, and low immunity.

A total of 120 COVID-19 patients were studied, with their baseline characteristics summarized in

Table 1. The median age distribution between the control group (n = 59) and the experimental group (n = 61) was similar, with no significant difference (

p = 0.657). In the control group, 42.4% (n = 25) were male and 57.6% (n = 34) were female, while in the experimental group, 39.3% (n = 24) were male and 60.7% (n = 37) were female, showing no significant difference in sex distribution (

p = 0.911). The distribution of underlying diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and others, was comparable between the two groups. No statistical analysis was performed for each individual condition due to the small number of patients per subgroup. Most participants in both groups reported no underlying diseases.

Table 2 presents the patient-reported severity levels of four key symptoms—fever and headache, sore throat, cough and mucus, and runny nose/nasal congestion—at baseline (Day 1) and on Days 3 and 7 after treatment. Symptom severity was assessed using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “worse” to “completely recovered.”

For fever and headache, significant differences between the experimental and control groups were observed at all time points. On Day 1, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the experimental group reported being “moderately improved,” “much better,” or having “no previous symptoms” (p = 0.038). By Day 3, the experimental group showed markedly greater improvement, with 13.1% reporting “much better” and 27.9% reporting “moderately improved,” compared to only 1.7% and 22.0%, respectively, in the control group (p < 0.001). On Day 7, complete recovery was more frequent in the experimental group (45.9% vs. 25.4%; p = 0.019), and no patients in either group reported worsening symptoms.

Regarding sore throat, no significant difference was observed on Day 1 (p = 0.605). However, by Day 3, the experimental group demonstrated significantly greater symptom improvement (p = 0.007), with higher rates of “moderately improved” (23.0% vs. 13.6%) and “much better” (11.5% vs. 1.7%). On Day 7, the experimental group exhibited significantly better outcomes (p < 0.001), including a higher rate of “completely recovered” (26.2% vs. 3.4%) and fewer reports of persistent or unchanged symptoms.

For cough and mucus, no significant difference was observed on Day 1 (p = 0.229). However, by Day 3, significant improvements were evident (p = 0.046), with more patients in the experimental group reporting being “moderately improved” (19.7% vs. 15.3%) or “much better” (11.5% vs. 1.7%). On Day 7, the difference remained significant (p = 0.011), with 14.8% of patients in the experimental group achieving complete recovery compared to only 1.7% in the control group.

As for runny nose and nasal congestion, the between-group difference approached significance on Day 1 (p = 0.072). A statistically significant difference was observed by Day 3 (p < 0.001), with a notably higher proportion of patients in the experimental group reporting being “much better” (21.3% vs. 1.7%) or “moderately improved” (19.7% vs. 13.6%). By Day 7, the improvement was even more pronounced (p < 0.001), with 31.1% of patients in the experimental group reporting complete recovery compared to only 3.4% in the control group, and no patients in either group reporting persistent or worsening symptoms.

Overall, the results suggest that the experimental treatment led to a more rapid and complete resolution of symptoms, particularly for sore throat, nasal congestion, and cough-related complaints. Notably, no patients in either group experienced a worsening of symptoms by Day 7, and no AEs were reported within 7 days of admission or during the 1-month follow-up after discharge.

Patient satisfaction was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale [

45], focusing on both symptom relief and product attributes such as color, smell, and taste.

Table 3 presents satisfaction levels after 7 days of antiviral product use in the experimental group (

n = 61) and control group (

n = 59). To compare the two groups, independent

t-tests were performed.

The results indicated that participants in the experimental group reported significantly higher satisfaction regarding symptom relief compared to those in the control group. Specifically, for relief of fever and headache, the experimental group had a mean satisfaction score of 4.02 ± 0.39, which was significantly higher than the control group’s score of 3.71 ± 0.53 (t = 3.60, p < 0.001). Similarly, for sore throat relief, the experimental group reported a mean score of 4.02 ± 0.34, compared to 3.69 ± 0.50 in the control group (t = 4.10, p < 0.001).

For cough and mucus relief, the experimental group demonstrated greater satisfaction (mean = 3.97, SD = 0.37) than the control group (mean = 3.63, SD = 0.55), with a statistically significant difference (t = 3.96, p < 0.001). A similar pattern was observed for relief of runny nose and nasal congestion, with the experimental group scoring 4.10 ± 0.40 versus 3.66 ± 0.55 in the control group (t = 5.02, p < 0.001).

In terms of product characteristics, participants in the experimental group also expressed higher satisfaction with the color, smell, and taste of the products (mean = 4.07 ± 0.36) compared to the control group (mean = 3.78 ± 0.50; t = 3.62, p < 0.001).

Overall satisfaction scores were significantly higher in the experimental group (mean = 4.03, SD = 0.30) than in the control group (mean = 3.69, SD = 0.48), with a t-value of 4.61 and p < 0.001.

These findings suggest that the antiviral products used in the experimental group were more effective in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms and were better received in terms of sensory attributes, resulting in significantly higher patient satisfaction.

4. Discussion

This clinical trial investigated the efficacy of newly developed nasal and mouth formulations for treating COVID-19. Our findings provide evidence that a nasal formulation containing D-limonene (0.2% w/w) and cetylpyridinium chloride (0.05% w/w), and a mouth formulation containing D-limonene (0.3% w/w), monolaurin (0.2% w/w), and cetylpyridinium chloride (0.05% w/w) can significantly improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients with moderate (yellow category) illness, within 7 days of treatment. Similarly, treatment with antiviral products was generally associated with a shorter time to symptom improvement and faster recovery, crucial for limiting virus spread. Throughout the entire follow-up period, no AEs were observed in any patients from either the experimental or control groups. The SARS-CoV-2-targeting products were found to be safe and well-tolerated in both treatment and control groups. Additionally, a complementary in vitro study demonstrated a high level of virucidal activity of the nasal and mouth formulations against SARS-CoV-2, a pathogen linked to significant clinical and socioeconomic challenges worldwide [

46]. In the present work, the virucidal agents in nasal spray, mouth spray, and mouthwash might prevent or mitigate COVID-19 transmission between household members, and thus preventing coronavirus spread among family members. The therapeutic effect of these formulations on SARS-CoV-2 has not been previously studied in a clinical trial; however, various studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of these natural product substances.

Recent studies have highlighted the antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects of D-limonene, monolaurin, and cetylpyridinium chloride. D-limonene, a compound found in lime and orange essential oils, has shown promise as an anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent due to its non-mutagenic, non-cytotoxic nature and favorable pharmacokinetics [

47,

48]. It has been shown to inhibit inflammatory mediators, reduce oxidative stress, and modulate immune responses [

49,

50,

51,

52], making it a potential therapeutic for COVID-19. Its antioxidant activity is particularly noteworthy, as oxidative stress and redox imbalances can worsen viral infections and contribute to viral mutations [

53,

54,

55].

Previous studies [

22,

56] have established that monolaurin possesses antibacterial, immune-enhancing, and antiviral properties, making it a valuable agent against viral infections. Monolaurin enhances immune function by modulating immune responses, controlling pro-inflammatory cytokines, and recruiting leukocytes to infection sites. Additionally, it exhibits antiviral activity, particularly against enveloped viruses like influenza and coronaviruses, by disrupting viral membranes, preventing viral protein binding, and inhibiting viral RNA assembly. These properties make monolaurin a promising candidate for boosting immune function and combating viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2.

Literature reviews suggested that mouth rinses containing cetylpyridinium chloride can reduce COVID-19 severity by lowering SARS-CoV-2 oral viral load and transmission risk from droplets or aerosols [

57,

58]. Cetylpyridinium chloride disrupted viral metabolism and cell membranes, showing superior antiviral activity against both enveloped and nonenveloped viruses compared to other agents like chlorhexidine [

59,

60]. Recent findings also indicated its effectiveness against influenza through a direct attack on the viral envelope, establishing it as a common ingredient in oral rinses, throat lozenges, and sprays [

61,

62].

D-limonene, monolaurin, and cetylpyridinium chloride possess the potential to mitigate the severity and progression of various diseases owing to their immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [

63,

64,

65,

66]. The efficacy of these compounds at low concentrations has been evaluated in several RCTs [

22,

67,

68]. Therefore, this study contributes to the existing experimental evidence regarding the potential additive clinical benefits of these compounds, leveraging their well-documented antiviral and antibacterial properties, as well as their safety record.

The role of developed products as antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory agents underscores their potential for treating COVID-19 patients. With their lipophilic structures and established use in various studies, they are recognized as safe, effective, and preferred adjuvants, enhancing symptom management in COVID-19 cases. Treatments targeting antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune modulation pathways have been explored as potential strategies for severe COVID-19 cases [

69,

70]. The results of this clinical trial suggest that administering developed products to SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with moderate (yellow category) illness may improve several clinical outcomes.

The study assessed patient satisfaction levels using a 5-point Likert scale, revealing a link between increased satisfaction (as shown in

Table 3) and decreased severity of COVID-19 symptoms (as indicated in

Table 2). While some patients experienced lingering symptoms after 7 days of product use, most expressed satisfaction. Notably, patients in the experimental group (receiving products with active ingredients) reported significantly higher satisfaction and better COVID-19 disease status compared to the control group (receiving products without active ingredients). For symptoms like fever, headache, sore throat, cough, mucus, runny nose, and nasal congestion, the experimental group consistently showed more "satisfied" and "very satisfied" responses, suggesting more effective symptom relief. In contrast, the control group had a higher percentage of neutral responses, indicating less noticeable improvement. None of the patients in either group reported being unsatisfied, suggesting both treatments were tolerable and beneficial. Further studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to confirm these findings and assess long-term outcomes.

This RCT indeed had several limitations. Firstly, it was designed at a time when there was limited data on SARS-CoV-2 viral kinetics and multiple viral strains were in circulation. Secondly, variations in nasal anatomy among patients, potentially including swollen nasal mucosa, were not fully accounted for. Thirdly, since patients self-administered the spray, there may have been differences in ability to correctly perform spraying and gargling techniques among individuals. Finally, the study was conducted during a period of prevalent Alpha and Delta variants. While these limitations are noteworthy, they also present opportunities for further research to address and refine the effectiveness of the interventions under investigation.

5. Conclusions

The findings from this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial provide clinical evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of nasal spray, mouth spray, and mouthwash containing limonene, cetylpyridinium chloride, and monolaurin in the management of mild-to-moderate COVID-19. Compared with placebo, the experimental formulations significantly accelerated symptom resolution, particularly in sore throat, cough with mucus, and nasal congestion, with notable improvements observed as early as Day 3. By Day 7, a greater proportion of patients in the experimental group reported complete recovery, and no symptom worsening or adverse events were observed. Moreover, patient satisfaction with both symptom relief and product characteristics was significantly higher in the experimental group. These results suggest that the tested antiviral products may serve as effective and well-tolerated adjunct therapies for symptomatic COVID-19 relief in outpatient settings. Further large-scale and multi-center studies are warranted to validate these findings and assess their long-term clinical utility.

Funding

This research was supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, Silpakorn University, Thailand, fiscal year 2025 [grant number: SURDI Postdoctoral/68].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chutima Limmatvapirat (CL), Sontaya Limmatvapirat (SL), Witoon Auparigtatipong (WA), and Manachai Ingsurarak (MI) conceptualized the study. CL, Juthaporn Ponphaiboon (JP), Wantanwa Krongrawa (WK) curated the data and performed formal analysis. CL secured funding for the project. CL, WA, JP, and WK contributed to the investigation. CL, SL, JP, and WA contributed to the methodology. CL, SL, WA, MI, JP, WK, Sukannika Tubtimsri (ST), Akanitt Jittmittraphap (AJ), Pornsawan Leaungwutiwong (PL), Chulabhorn Mahidol (CM), Somsak Ruchirawat (SR), and Prasat Kittakoop (PK), were involved in project administration. CL and SL provided resources. CL supervised the project. CL and WA validated the findings. CL visualized the data. CL drafted the original manuscript. CL and PK reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Pharmacy, Silpakorn University, Thailand, and Dontum Hospital, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, for providing a supportive environment for this study. We also acknowledge the valuable support from the Chulabhorn Research Institute, the Laboratory of Natural Products and Medicinal Chemistry, and the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that they have no financial interests in the patents related to the formulations used in this study.

References

- World Health Organization, Advice for the public: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), World Health Organization, 2023.

- S. Perlman, Another decade, another coronavirus, N. Engl. J. Med. 382(8) (2020) 1–2. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Peiris, C.M. Chu, V.C. Cheng, et al., Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study, Lancet 361(9371) (2003) 1767–1772. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, X. Guan, P. Wu, et al., Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia, N. Engl. J. Med. 382(13) (2020) 1199–1207. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang, Y. Wang, X. Li, et al., Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, Lancet 395(10223) (2020) 497–506. [CrossRef]

- N. Chen, M. Zhou, X. Dong, et al., Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study, Lancet 395(10223) (2020) 507–513. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Rothan, S.N. Byrareddy, The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, J. Autoimmun. 109 (2020) 102433. [CrossRef]

- W. Ni, X. Yang, D. Yang, et al., Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19, Crit. Care 24(1) (2020) 422. [CrossRef]

- R. Wölfel, V.M. Corman, W. Guggemos, et al., Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019, Nature 581(7809) (2020) 465–469. [CrossRef]

- L. Zou, F. Ruan, M. Huang, et al., SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients, N. Engl. J. Med. 382(12) (2020) 1177–1179. [CrossRef]

- D. Panatto, A. Orsi, B. Bruzzone, et al., Efficacy of the Sentinox spray in reducing viral load in mild COVID-19 and its virucidal activity against other respiratory viruses: results of a randomized controlled trial and an in vitro study, Viruses 14(5) (2022) 1033. [CrossRef]

- S. Alsaleh, A. Alhussien, A. Alyamani, et al., Efficacy of povidone-iodine nasal rinse and mouth wash in COVID-19 management: a prospective, randomized pilot clinical trial (povidone-iodine in COVID-19 management), BMC Infect. Dis. 24 (2024) 271. https://doi.org /10.1186/s12879-024-09137-y.

- M. Idrees, B. McGowan, A. Fawzy, A.A. Abuderman, R. Balasubramaniam, O. Kujan, Efficacy of mouth rinses and nasal spray in the inactivation of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro and in vivo studies, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(19) (2022) 12148. [CrossRef]

- E.R. Anderson, E.I. Patterson, S. Richards, et al., CPC-containing oral rinses inactivate SARS-CoV-2 variants and are active in the presence of human saliva, J. Med. Microbiol. 71 (2022) 001508. [CrossRef]

- N. Okamoto, A. Saito, T. Okabayashi, A. Komine, Virucidal activity and mechanism of action of cetylpyridinium chloride against SARS-CoV-2, J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 34(6) (2022) 800–804. [CrossRef]

- Z. Low, R. Lani, V. Tiong, C. Poh, S. AbuBakar, P. Hassandarvish, COVID-19 therapeutic potential of natural products, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(11) (2023) 9589. [CrossRef]

- A.N.R. Corrêa, P. Weimer, R.C. Rossi, J.F. Hoffmann, L.S. Koester, E.S. Suyenaga, C.D. Ferreira, Lime and orange essential oils and d-limonene as a potential COVID-19 inhibitor: Computational, in chemico, and cytotoxicity analysis, Food Biosci. 51 (2023) 102348. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang, R. Chen, W. Li, et al., D-limonene is a potential monoterpene to inhibit PI3K/Akt/IKK-α/NF-κB p65 signaling pathway in coronavirus disease 2019 pulmonary fibrosis, Front. Med. 8 (2021) 591830. [CrossRef]

- H. Lin, Z. Li, Y. Sun, et al., D-Limonene: promising and sustainable natural bioactive compound, Appl. Sci. 14 (2024) 4605. [CrossRef]

- Falk-Filipsson, A. Löf, M. Hagberg, E.W. Hjelm, Z. Wang, d-limonene exposure to humans by inhalation: uptake, distribution, elimination, and effects on the pulmonary function, J. Toxicol. Environ. Health (1993) 77-88. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Miller, I.A. Hakim, W. Chew, P. Thompson, C.A. Thomson, H.S. Chow, Adipose tissue accumulation of d-limonene with the consumption of a lemonade preparation rich in d-limonene content, Nutr. Cancer 62(6) (2010) 783–788. [CrossRef]

- L.A. Barker, B.W. Bakkum, C. Chapman, The clinical use of monolaurin as a dietary supplement: a review of the literature, J. Chiropr. Med. 18(4) (2019) 305–310. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Kabara, R. Vrable, M.S.F. Lie Ken Jie, Antimicrobial lipids: natural and synthetic acids and monoglycerides, Lipids 12(9) (1977) 753–759. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Projan, S. Brown-Skrobot, P.M. Schlievert, F. Vandenesch, R.P. Novick, Glycerol monolaurate inhibits the production of β-lactamase, toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 and other staphylococcal exoproteins by interfering with signal transduction, J. Bacteriol. 176(14) (1994) 4204–4209. [CrossRef]

- E. Subroto, R. Indiarto, Bioactive monolaurin as an antimicrobial and its potential to improve the immune system and against COVID-19: a review, Food Res. 4(6) (2020) 2355–2365. [CrossRef]

- Y. Weerapol, S. Manmuan, S. Limmatvapirat, C. Limmatvapirat, J. Sirirak, P. Tamdee, S. Tubtimsri, Enhancing the efficacy of monolaurin against SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A (H1N1) with a nanoemulsion formulation, OpenNano 17 (2024) 100207. [CrossRef]

- G.L. Drusano, Infection site concentrations: their therapeutic importance and the macrolide and macrolide-like class of antibiotics, Pharmacotherapy 25(12 Pt 2) (2005) 150S–158S. [CrossRef]

- T. Fazekas, P. Eickhoff, N. Pruckner, et al., Lessons learned from a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study with a iota-carrageenan nasal spray as medical device in children with acute symptoms of common cold, BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12 (2012) 147. [CrossRef]

- F. Fais, R. Juskeviciene, V. Francardo, et al., Drug-free nasal spray as a barrier against SARS-CoV-2 and its delta variant: in vitro study of safety and efficacy in human nasal airway epithelia, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(7) (2022) 4062. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Pelletier, B. Tessema, S. Frank, J.B. Westover, S.M. Brown, J.A. Capriotti, Efficacy of povidone-iodine nasal and oral antiseptic preparations against severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Ear Nose Throat J. 100(2_suppl) (2021) 192S–196S. [CrossRef]

- K.F. Schulz, D.G. Altman, D. Moher, CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials, BMJ 340 (2010) c332. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Living Guidance for Clinical Management of COVID-19, World Health Organization, 2021.

- J. Ponphaiboon, W. Krongrawa, S. Limmatvapirat, S. Tubtimsri, A. Jittmittraphap, P. Leaungwutiwong, C. Mahidol, S. Ruchirawat, P. Kittakoop, C. Limmatvapirat, In vitro development of local antiviral formulations with potent virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses, Pharmaceutics 17 (2025) 349. [CrossRef]

- C. Mahidol, S. Ruchirawat, W. Sutananta, P. Kittakoop, N. Wanichacheva, S. Limmatvapirat, C. Limmatvapirat, P. Leaungwutiwong, A. Jittmittraphap, S. Tubtimsri, J. Ponphaiboon, and W. Krongrawa, Antiviral product for oral and throat and production method, Thai Petty Patent no. 20893, 2022.

- C. Mahidol, S. Ruchirawat, W. Sutananta, P. Kittakoop, N. Wanichacheva, S. Limmatvapirat, C. Limmatvapirat, P. Leaungwutiwong, A. Jittmittraphap, S. Tubtimsri, J. Ponphaiboon, and W. Krongrawa, Nasal spray product for killing viruses and production method, Thai Petty Patent no. 20894, 2022.

- Gupta, E. Jeyakumar, R. Lawrence, Journey of limonene as an antimicrobial agent, J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 15 (3) (2021) 1094–1110. [CrossRef]

- E. Subroto, Monoacylglycerols and diacylglycerols for fat-based food products: a review, Food Res. 4 (4) (2020) 932–943. [CrossRef]

- M. Bañó-Polo, L. Martínez-Gil, M.M. Sánchez del Pino, A. Massoli, I. Mingarro, R. Léon, M.J. Garcia-Murria, Cetylpyridinium chloride promotes disaggregation of SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particles, J. Oral Microbiol. 14 (1) (2022) 2030094. [CrossRef]

- Y. Weerapol, S. Manmuan, S. Limmatvapirat, C. Limmatvapirat, J. Sirirak, P. Tamdee, S. Tubtimsri, Enhancing the efficacy of monolaurin against SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A (H1N1) with a nanoemulsion formulation, OpenNano 17 (2024) 100207. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Rodríguez-Casanovas, M.D.I. Rosa, Y. Bello-Lemus, G. Rasperini, A.J. Acosta-Hoyos, Virucidal activity of different mouthwashes using a novel biochemical assay, Healthcare 10 (2022) 63. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Parikh-Das, N.C. Sharma, Q. Du, C.A. Charles, Superiority of essential oils versus 0.075% CPC-containing mouthrinse: a two-week randomized clinical trial, J. Clin. Dent. 24 (3) (2013) 94–99.

- M.Z.I. Chowdhury, K.C. Sikdar, T.C. Turin, Sample size calculation in clinical studies: Some common scenarios, Int. J. Stat. Med. Res. 6 (4) (2017) 152–161. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health, World Health Organization, 2023.

- Alhassan, N. Asiamah, F.F. Opuni, A. Alhassan, The Likert scale: exploring the unknowns and their potential to mislead the world, UDS Int. J. Dev. 9 (2) (2022) 867–880. [CrossRef]

- C. Chong, Dividing the emergency department into red, yellow, and green zones to control COVID-19 infection; a letter to editor, Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 8 (1) (2020) e60.

- M. Nicola, Z. Alsafi, C. Sohrabi, A. Kerwan, A. Al-Jabir, C. Iosifidis, M. Agha, R. Aghaf, The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review, Int. J. Surg. 78 (2020) 185–193. [CrossRef]

- A.N.R. Corrêa, P. Weimer, R.C. Rossi, J.F. Hoffmann, L.S. Koester, E.S. Suyenaga, D. Ferreira, Lime and orange essential oils and D-limonene as a potential COVID-19 inhibitor: computational, in chemico, and cytotoxicity analysis, Food Biosci. 51 (2023) 102348. [CrossRef]

- N.Q. Fadilah, A. Jittmittraphap, P. Leaungwutiwong, P. Pripdeevech, D. Dhanushka, C. Mahidol, S. Ruchirawat, P. Kittakoop, Virucidal activity of essential oils from Citrus × aurantium L. against influenza A virus H1N1: limonene as a potential household disinfectant against virus, Nat. Prod. Commun. 17 (1) (2022) 1–7. [CrossRef]

- S.C. Chaudhary, M.S. Siddiqui, M. Athar, M.S. Alam, D-limonene modulates inflammation, oxidative stress and Ras-ERK pathway to inhibit murine skin tumorigenesis, Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 31 (8) (2012) 798–811. [CrossRef]

- Razazi, A. Kakanezhadi, A. Raisi, B. Pedram, O. Dezfoulian, F. Davoodi, D-limonene inhibits peritoneal adhesion formation in rats via anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, and antioxidative effects, Inflammopharmacology 32 (2) (2024) 1077–1089. [CrossRef]

- M.F.N. Meeran, A. Seenipandi, H. Javed, C. Sharma, H.M. Hashiesh, S.N. Goyal, N.K. Jha, S. Ojha, Can limonene be a possible candidate for evaluation as an agent or adjuvant against infection, immunity, and inflammation in COVID-19?, Heliyon 7 (1) (2021) e05703. [CrossRef]

- M. Bacanlı, A.A. Başaran, N. Başaran, The antioxidant and antigenotoxic properties of citrus phenolics limonene and naringin, Food Chem. Toxicol. 81 (2015) 160–170. [CrossRef]

- E.S. Keles, Mild SARS-CoV-2 infections in children might be based on evolutionary biology and linked with host reactive oxidative stress and antioxidant capabilities, New Microbes New Infect. 36 (2020) 100723. [CrossRef]

- Khomich, S.N. Kochetkov, B. Bartosch, A.V. Ivanov, Redox biology of respiratory viral infections, Viruses 10 (8) (2018) 392. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Beck, J. Handy, O.A. Levander, Host nutritional status: the neglected virulence factor, Trends Microbiol. 12 (9) (2004) 417–423. [CrossRef]

- E. Subroto, R. Indiarto, Bioactive monolaurin as an antimicrobial and its potential to improve the immune system and against COVID-19: a review, Food Res. 4 (6) (2020) 2355–2365. [CrossRef]

- D. Herrera, J. Serrano, S. Roldán, M. Sanz, Is the oral cavity relevant in SARS-CoV-2 pandemic?, Clin. Oral Investig. 24 (8) (2020) 2925–2930. [CrossRef]

- G.D. Kumar, A. Mishra, L. Dunn, A. Townsend, I.C. Oguadinma, K.R. Bright, C.P. Gerba, Biocides and novel antimicrobial agents for the mitigation of coronaviruses, Front. Microbiol. 11 (2020) 1351. [CrossRef]

- T. Nagatake, K. Ahmed, K. Oishi, Prevention of respiratory infections by povidone-iodine gargle, Dermatology 204 (Suppl. 1) (2002) 32–36. [CrossRef]

- R. Kawana, T. Kitamura, O. Nakagomi, et al., Inactivation of human viruses by povidone-iodine in comparison with other antiseptics, Dermatology 195 (Suppl. 2) (1997) 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Steyer, M. Marušić, M. Kolenc, T. Triglav, A throat lozenge with fixed combination of cetylpyridinium chloride and benzydamine hydrochloride has direct virucidal effect on SARS-CoV-2, COVID 1 (2) (2021) 435–446. [CrossRef]

- D.L. Popkin, S. Zilka, M. Dimaano, H. Fujioka, C. Rackley, R. Salata, A. Griffith, P.K. Mukherjee, M.A. Ghannoum, F. Esper, Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) exhibits potent, rapid activity against influenza viruses in vitro and in vivo, Pathog. Immun. 2 (2) (2017) 253–269. [CrossRef]

- W. Luo, K. Wang, J. Luo, et al., Limonene anti-TMV activity and its mode of action, Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 194 (2023) 105512. [CrossRef]

- P.M. Schlievert, S.H. Kilgore, K.S. Seo, D.Y.M. Leung, Glycerol monolaurate contributes to the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of human milk, Sci. Rep. 9 (1) (2019) 14550. [CrossRef]

- S.L.F. Miranda, J.T. Damaceno, M. Faveri, L.C. Figueiredo, G.M.S. Soares, M. Feres, B. Bueno-Silva, In vitro antimicrobial effect of cetylpyridinium chloride on complex multispecies subgingival biofilm, Braz. Dent. J. 31 (2) (2020) 103–108. [CrossRef]

- G. LeBel, K. Vaillancourt, M. Morin, D. Grenier, Antimicrobial activity, biocompatibility and anti-inflammatory properties of cetylpyridinium chloride-based mouthwash containing sodium fluoride and xylitol: An in vitro study, Oral Health Prev. Dent. 18 (1) (2020) 1069–1076. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun, D-limonene: Safety and clinical applications, Altern. Med. Rev. 12 (3) (2007) 259–264. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18072821/.

- R. Tarragó-Gil, M.J. Gil-Mosteo, M. Aza-Pascual-Salcedo, et al., Randomized clinical trial to assess the impact of oral intervention with cetylpyridinium chloride to reduce salivary SARS-CoV-2 viral load, J. Clin. Periodontol. 50 (3) (2023) 288–294. [CrossRef]

- S. Felsenstein, J.A. Herbert, P.S. McNamara, C.M. Hedrich, COVID-19: immunology and treatment options, Clin. Immunol. 215 (2020) 108448. [CrossRef]

- R. Cecchini, A.L. Cecchini, SARS-CoV-2 infection pathogenesis is related to oxidative stress as a response to aggression, Med. Hypotheses 143 (2020) 110102. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).