1. Introduction

Brazilian biodiversity comprises over 20% of the total species of higher plants (20–22% of the total in the world), beyond biodiversity, there is a wide diversity of traditional medicine with European and African and native Indigenous knowledge, including on medicinal plants (also known as herbal medicines) [

1,

2]. Although long-term traditional use could suggest a kind of proof of safety and efficacy, potential agents, even traditional medicinal plants, need to be evaluated using current scientific approaches and methodologies to verify safety and efficacy [

1].

In this context, it has been recognized that traditional medicinal plants can be useful for the management of mild respiratory diseases symptoms, such as cough and fever [

3]. Inflorescence infusions of a South American species,

Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) D. C. (Asteraceae), called “marcela” or “macela”, has been widely used for the treatment of several diseases, including respiratory infections [

4]. Recently, adding evidence to ethnopharmacological profile [

5], our group reported preliminary results, without complete follow-up, of beneficial effects of

Achyrocline satureioides inflorescence infusion on viral respiratory infections symptoms, including those induced by SARS-CoV-2 in a clinical trial. Interestingly,

A. satureioides infusion improved the latency to resolution of fever, sore throat, the respiratory symptoms of cough and dyspnea, and neurological symptoms of smell and taste dysfunctions compared with the control group (

M. domestica infusion) [

6]. To investigate the clinical efficacy of a 14-day course of an

A. satureioides inflorescence infusion twice a day for the management of mild viral respiratory infections symptoms, including those induced by COVID-19, we conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, and open-label clinical trial. Here, we describe an update to the preliminary report [

6] after complete follow-up.

2. Results

2.1. Participants and Baseline Characteristics

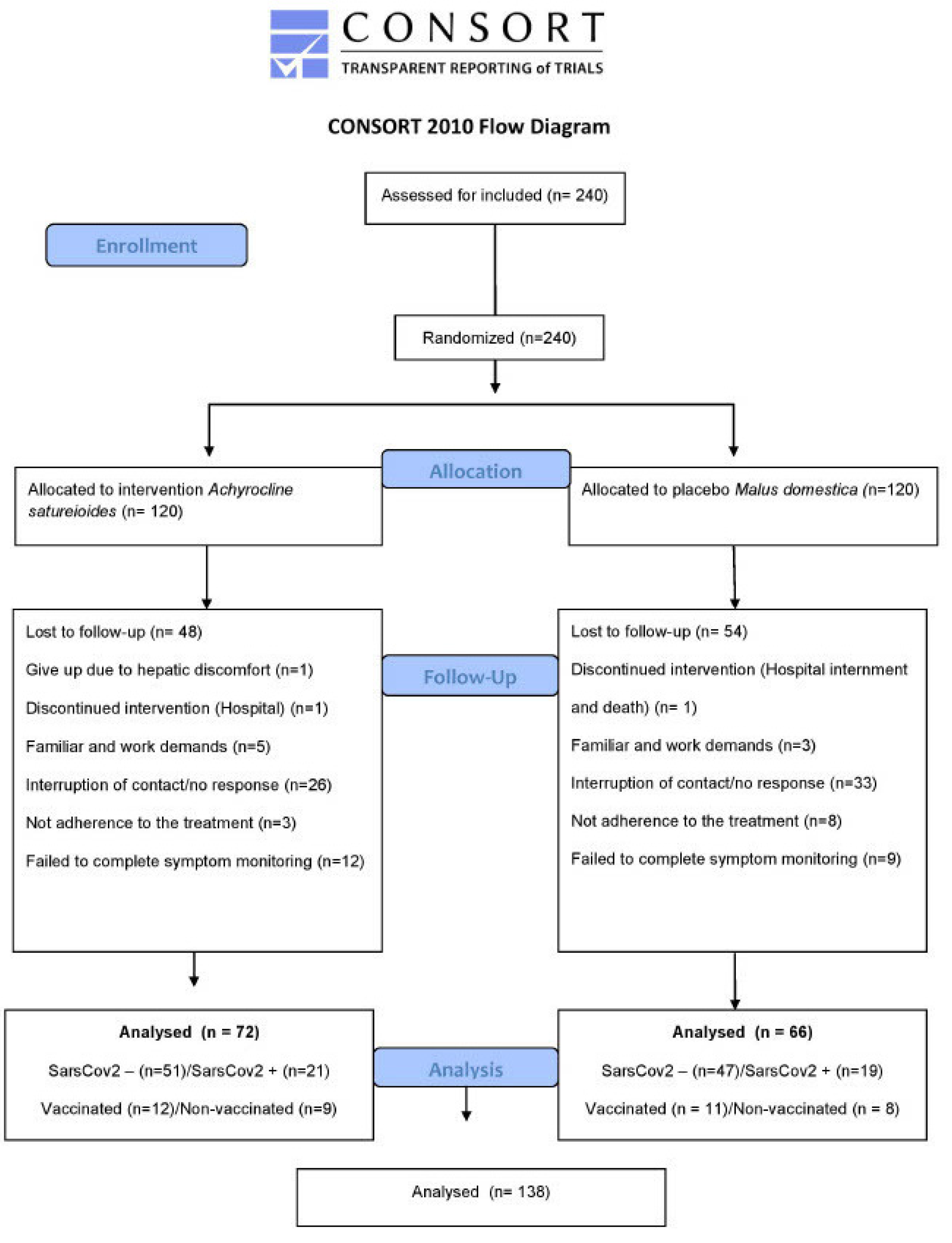

We collected data between March 24, 2021, and December 6th, 2021. 240 participants were assessed for eligibility and underwent randomization.

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram. Of the 240 eligible participants included in the study, 138 completed symptom monitoring, 72 in the

A. satureioides group and 66 in the

M. domestica group. Participants withdrew during the follow-up due to family or work demands, a lack of time to prepare the infusion and fear of exposure to COVID-19. There was no significant difference on lost to follow-up between

A. satureioides infusion and

M. domestica infusion groups (Chi squarer’s test, p = 0.4). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are reported in

Table 1. Both groups were comparable in terms of baseline characteristics.

2.2. Overall Analysis

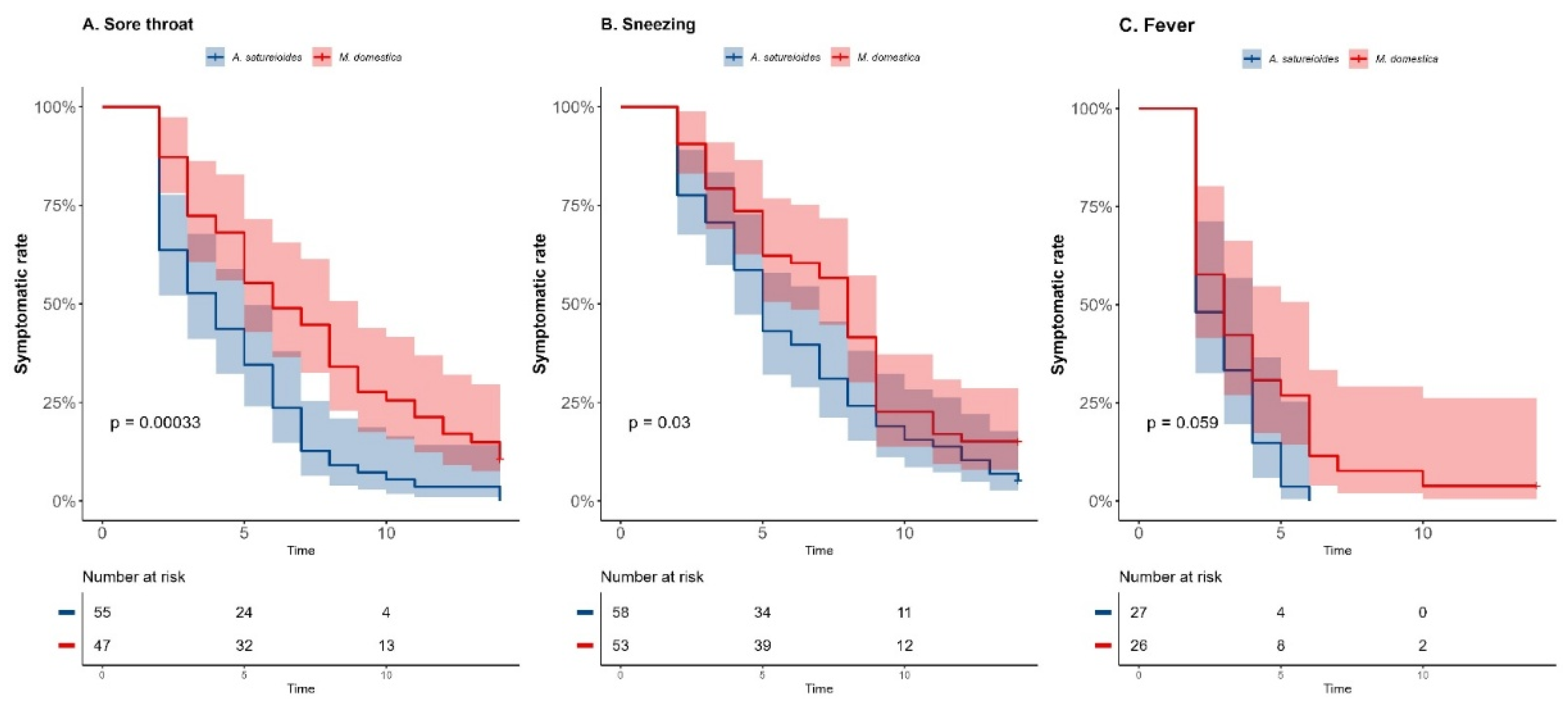

A. satureioides infusion significantly impacts the recovery time for some respiratory symptoms, the primary outcome, specifically sore throat and sneezing, compared with

M. domestica group in the overall analysis (

Figure 2A,B). Shorter median time suffering from sore throat was observed in the

A. satureioides group (4 days [95% CI, 2 to 5] vs.

M. domestica group, 6 days [95% CI, 5 to 8], p<0.01; HR=2.13 [95% CI, 1.41 to 3.24, p<0.01). In addition, the latency to remission of sneezing - 5 days [95% CI, 4 to 7] vs. 8 days [95% CI, 5 to 9]; p=0.03; HR=1.50 [95% CI, 1.01 to 2.23], p=0.043) was observed.

In accordance, the rate of symptom recovery on day 8 was significantly higher in

A. satureioides group compared with

M. domestica group for sore throat (87.2% [48] vs 55.3% [

26], p=0.0003) and for sneezing (68.9% [40] vs 43.3% [

23], p=0.007). Fisher’s exact test indicated a trend for an effect of

A. satureioides on the rate of symptom recovery for sore throat on day 14 in the overall analysis (96.3% [53] vs 85.1% [40], p=0.077). A.

satureioides group showed 2 days (95% CI, 2 to 4) to recover from fever, while

M. domestica infusion group had 3 days (95% CI, 2 to 4), with a trend towards statistical significance (

Figure 2C, p =0.059). In accordance, the Hazard Ratio (HR) from fever was 1.71 ([95% CI, 0.95 to 3.07], p=0.06). An effect of

A. satureioides infusion on the rate of dyspnea recovery at the 8 day was also observed in the overall analysis (62.1% [

23] vs 40% [

18], p=0.046) (Supplementary

Figure 1A). Although

the A. satureioides infusion group seems to have faster respiratory recovery, specifically sore throat and sneezing, there were no significant differences between

A. satureioides group and

M. domestica group on cough (Supplementary

Figure 1B). As well as non-respiratory symptoms, such as loss of appetite, earache and body ache, did not reach any statistical significance in the overall analysis (Supplementary Figures 1C–E).

2.3. Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis considering vaccination status against SARS-CoV-2 (vaccinated and non-vaccinated participants) and COVID-19 infection (SARS-CoV-2+ or SARS-CoV-2-) were performed.

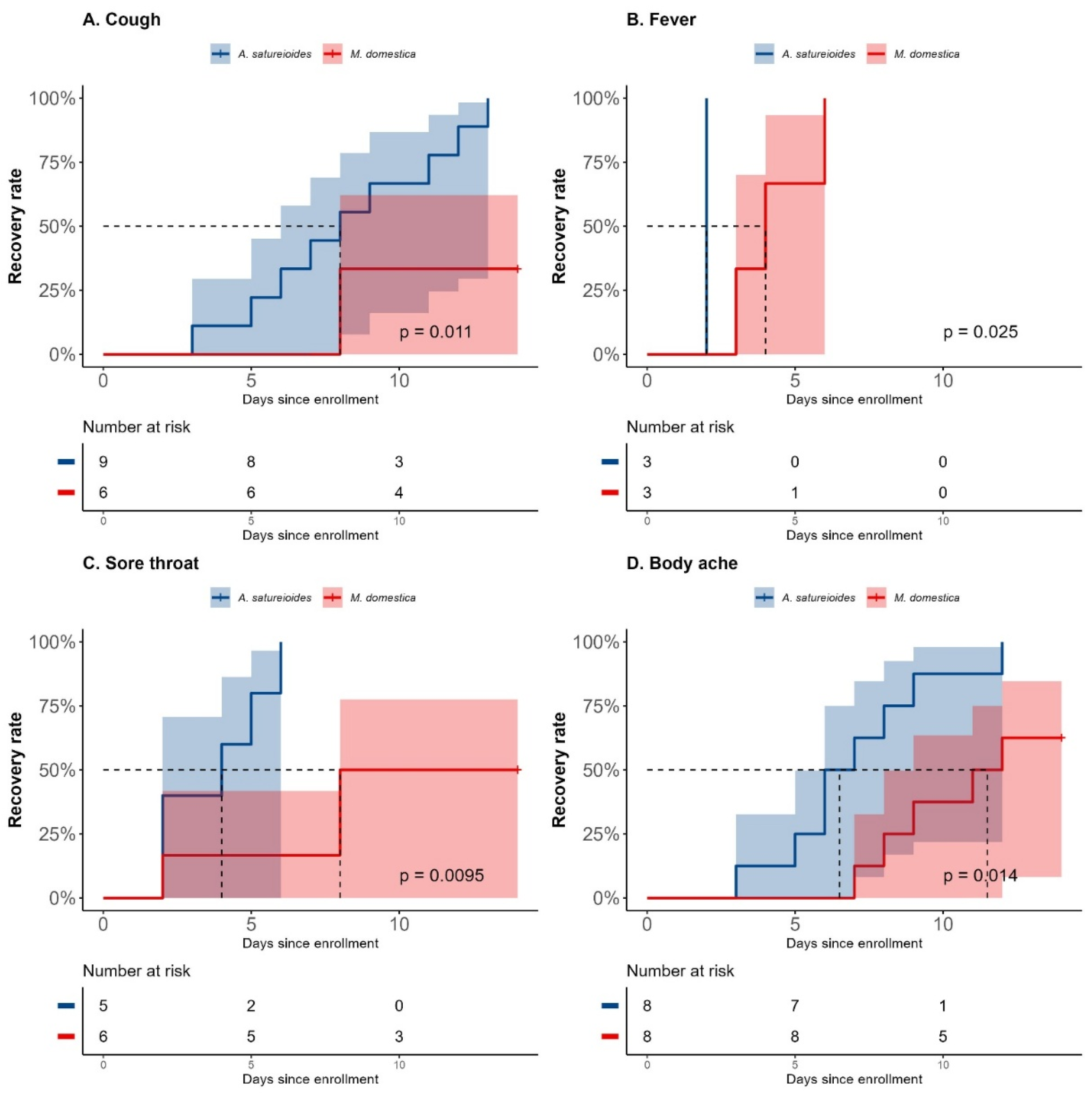

In the subgroup analyses, participants who were non-vaccinated SARS-CoV-2 positive and received

A. satureioides infusion had significantly fewer days with cough (8 [95% CI 3 to 12] vs NE [8 to NE], p=0.011; HR: 5.74 [95% CI: 1.19 to 27.55], p=0.02;

Figure 3A). In accordance, on day 14,

A. satureioides infusion group also had higher recovery rates when compared to

M. domestica for cough (100% [

9] vs 33.33% [

2], p=0.01) among those SARS-CoV2 positive participants.

A. satureioides infusion in non-vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup induced faster resolution on fever (2 [95% CI, NE to NE] vs 4 [95% CI, 3 to NE], p=0.025) and sore throat (4 days [95% CI, 2 to not estimable, (NE)] vs 8 days [95% CI, 2 to NE], p<0.01; HR=10.33 [95% CI, 1.15 to 92.27], p=0.03) (

Figure 3B,C). A statistically significant effect of

A. satureioides infusion was observed on the rate of sore throat recovery in non-vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive participants on day 8 (100% [

5] vs 16.6% [

1], p=0.01). In addition,

A. satureioides infusion improved the body ache recovery (6.5 days [95% CI, 3 to 9] vs 11.5 days [95% CI, 7 to NE], p=0.014; HR: 4 [95% CI: 1.25 to 12.73], p=0.01) with a rate of recovery of 75% [

6] compared with the

M. domestica infusion group (25% [

2], p=0.052) (

Figure 3D). There were no significant differences between

A. satureioides group and

M. domestica groups in non-vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive participants on dyspnea, sneezing earache and loss of appetite (Supplementary Figures 2A–D).

However, there was a significant impact of vaccination status. For example, vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup that received

M. domestica showed approximately 7 (4-9; average = 8.2 days) days suffering with cough, while the survival analysis was unable to estimate the median value, because few patients (less of 50%) achieved the resolution on Day 14 in the non-vaccinated ones (average = 12 days, p=0.034) (Supplementary

Figure 4). In addition, no significant differences between the

M. domestica infusion group and the

A. satureioides group of median time to recovery for any evaluated symptoms in the vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup (Supplementary Figures 3A–D).

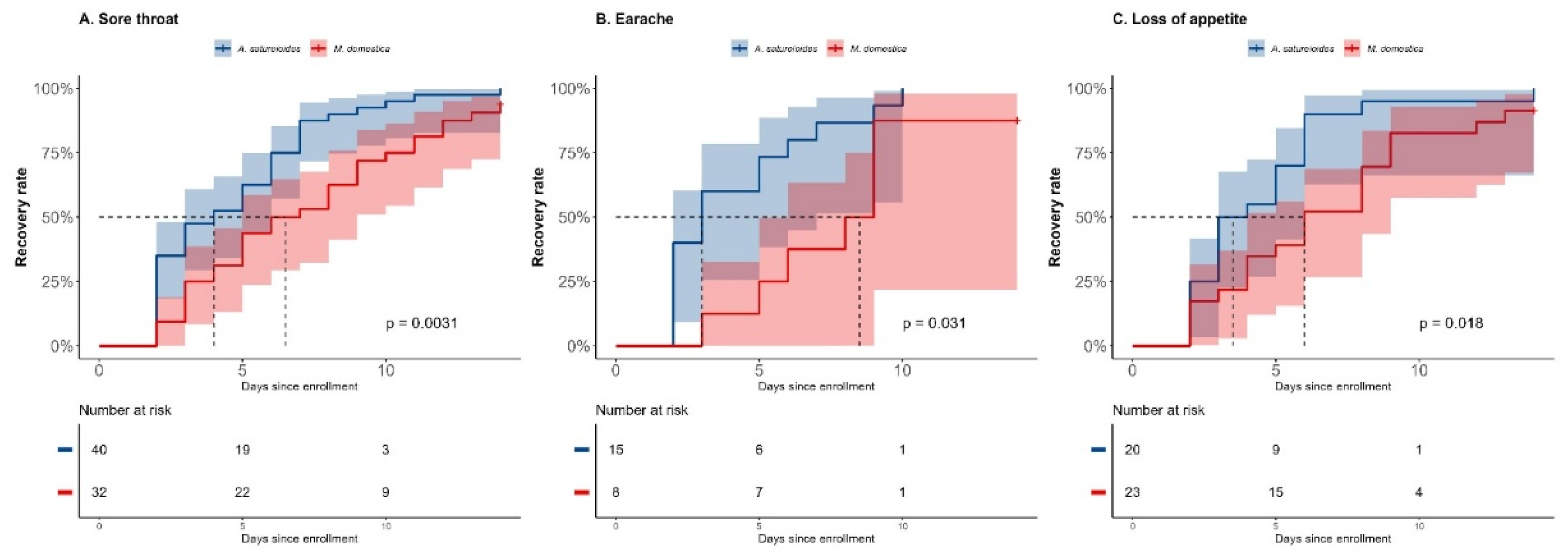

SARS-CoV2 negative that received

A. satureioides subgroup had a significant faster recovery time for sore throat as well (4 days [95% CI, 2 to 6] vs 6.5 days [95% CI, 4 to 9], p<0.01; HR=2.09 [95% CI, 1.28 to 3.42], p<0.01). There was a significantly higher rate of recovery for sore throat on day 8 (87.5% [35] vs 53.1% [

17], p=0.001;

Figure 4A).

The recovery time for each was impacted by

A. satureioides infusion (3 days [95% CI, 2 to 5] vs 8.5 days [95% CI, 3 to 9], p=0.031; HR: 2.49 [95% CI: 0.98 to 6.15], p=0.052) and the rate recovery on day 8 was 86.6% [

13] while for

M. domestica group was 37.5% [

3] (p=0.026) in the SARS-CoV2 negative subgroup (

Figure 4B). In this subgroup, the use of

A. satureioides infusion resulted in a shorter time suffering of loss of appetite (3 days [95% CI, 2 to 5] vs 6 days [95% CI, 4 to 8], HR: 2.14 [95% CI: 1.13 to 4.06], both p=0.018) with a significant rate of recovery on day 8 (90% [

18] vs 52.1% [

12]; p=0.009;

Figure 4C). In addition,

A. satureioides infusion improved the rate of dyspnea recovery on day 8 (64% [

16] vs 36.3% [

12]; p=0.037), comparing with the control group,

M. domestica infusion, as well as the sneezing recovery rate (65.8% [

27] vs 42.1% [

16], p=0.034).

2.4. Safety

No serious adverse events were reported, only one participant within the Achyrocline satureioides group reported a mild adverse event, specifically gastrointestinal discomfort, leading to withdrawal from the study.

3. Discussion

Our data support the hypothesis that A. satureioides infusions twice a day for 14 days can induce significantly faster symptoms recovery and may improve the rate of recovery of respiratory infection diseases symptoms, including in symptomatic patients of mild COVID-19, comparing with control group, Malus domestica infusion. We found significant alleviation of several symptoms, sore throat, sneezing, cough, body ache, fever, earache and loss of appetite. Beyond the efficacy of A. satureioides on respiratory infections symptoms, it is possible to describe that administration of A. satureioides infusions appears to be generally well-tolerated and safe.

A. satureioides infusion had a more significant impact on sore throat in the overall analysis, as well as if non-vaccinated SARS-CoV-2-positive and SARS-CoV-2-negative subgroups were considered. Sore throat is related to respiratory mucosa of the throat infection induced by several viruses, in addition to coronavirus and rhinovirus, also respiratory syncytial virus and Epstein–Barr virus, and by bacteria species, such as

Streptococcus sp,

Haemophilus influenzae and

Moraxella catarrhalis; however, most of sore throat cases seems to have virus as causative organisms [

7].

Several medicinal plants/herbal drugs/phytomedicines have been evaluated for the management of symptoms in patients with coronavirus 2019 disease [

8,

9]. Briefly, non-vaccinated SARS-CoV-2-positive patients had improvements on cough, body ache, sore throat and fever recovery by

A. satureioides infusion. In addition, sore throat, loss of appetite, earache and dyspnea showed faster resolution in the SARS-CoV-2-negative subgroup.

Considering the profile of

A. satureioides–impacted symptoms, it is possible to suggest the anti-inflammatory properties as a central mechanism of action. In accordance, an hydroalcoholic extract obtained from

A. satureioides inflorescences reduced neutrophil trafficking and levels of inflammatory mediators in a model of inflammation induced by injection of lipopolysaccharide into the subcutaneous tissue of male Wistar rats [

10]. In a study conducted by De Souza, Basani and Schapoval [

11], evaluating the anti-inflammatory effect of

A. satureioides spray-dried and freeze-dried powders in a carrageenan-induced rat paw edema model, described significant antiedematogenic properties and a reduction of the total leukocyte and polymorphonuclear cell migration in the pleural cavity for the extracts.

Although it is impossible to indicate at this moment exactly which phytocompound(s) is(are) responsible for the huge effects of

A. satureioides infusion, their flavonoids can be considered as relevant candidates. Di Pierro et al. [

12] conducted a clinical trial in order to observe the effects of oral quercetin supplement (500 mg) for one week in patients infected with SARS-CoV2. Compared to placebo groups, participants using quercetin had faster recovery of symptoms and tested negative earlier in the follow-up. Araújo et al. [

13] showed the quercetin ability to prevent lung injury caused by cigarette smoke quercetin using in vitro and in vivo models, pulmonary parenchyma and lung function were protected due antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of quercetin [

13]. Another potential mechanism can be raised based on in vitro findings, since quercetin was able to relax airway smooth muscle of tracheal rings from mice upon exposure to acetylcholine, similarly to methylxanthines, quercetin inhibited the phosphodiesterase activity, a known mechanism of anti-asthmatics [

14], what can be involved with our findings on cough and dyspnea improvements induced by

A. satureioides infusions.

In addition, antiviral activity of quercetin may have contributed to symptoms improvements, however the antiviral mechanism of action of quercetin is not widely well understood. Quercetin is able to bind to the glycoprotein hemagglutinin of influenza A virus, inhibiting virus entry into host cells [

15]. Concerning SARS-CoV2, quercetin binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) spike protein preventing virus-host recognition and the virus entrance on the host cell [

16]. An in vitro study has shown that quercetin inhibits syncytium formation in cells coexpressing the viral spike protein and human ACE2 [

17]. Furthermore, a molecular docking study reported that quercetin inhibits the transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), a crucial protease involved in the proteolytic cleavage of SARS-Cov-2 spike protein and consequently for its activation and binding to the ACE2 receptor [

18]. Additionally, quercetin prevents viral replication suppressing the activity of 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), a key enzyme involved in viral replication [

16].

It is relevant to point out that the early intervention begin (at the first medical care seeking) was based on previously described preclinical antiviral activities of

A. satureioides [

5] and the role of viral replication levels in the first week of symptoms in the COVID-19 [

19]. Given that COVID-19 diagnosis by RT-PCR lasted up to 3-day, the inclusion and intervention happen already at the first medical care seeking.

The findings on the final, all-randomized sample analysis here reported were mainly consistent with those of the preliminary report with an interim analysis [

6], a faster improvement of symptoms induced by

A. satureioides infusion. It is relevant to note that this preliminary report included data collection from participants between March 24th to May 24th of 2021, at that moment only 18% of COVID-19 participants were vaccinated, because the vaccines were not properly and widely distributed in our country. During the second phase of data collection, which happened between July 26th and November 23rd, all the included COVID-19 participants were already vaccinated, resulting in a total of 52,4% of the vaccinated participants with COVID-19 in the final analysis. The vaccination impacted the severity of clinical outcomes, the vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup even those receiving

M. domestica infusion showed faster resolution, in accordance with previous findings [

20]. Interestingly, we did not observe a synergistic effect between vaccines and

A. satureioides infusion to recovery for any evaluated symptoms in the vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup.

Although the high efficacy rated of vaccines against SARS-CoV2-induced infections is unarguable, new mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genome have been described and some variants can reduce the effects of antibodies generated by both infection and vaccination [

21], which can be associated with reduced vaccine efficacy and increased transmissibility and risk of reinfection [

22], bringing the need of new effective approaches for COVID-19, including those based on traditional medicine [

23].

Our study had potential limitations. Firstly, our findings are based on an open label trial, it is impossible to conduct this trial with a double-blind design, because of the differences in taste, smell and visual of the infusions. However, to avoid or reduce this bias, the participants received information about the project, including in the written informed consent form, as the central aim was to compare the effects of plants containing phenolic compounds, “apple” and “marcela” [

6]. The low rates of adherence (high lost- to follow-up) can be a research bias, leading to misinterpretation, impacting the internal validity. In addition, older adults seem to accept the inclusion easier and demonstrate a good adherence level compared to adults and young adults, limiting the generalizability of the findings.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Considerations

The ethics committee of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul study approved this protocol (4.514.201) that was registered at the Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trial (ReBEC, RBR-8g6f2rv).

4.2. Trial Design and Randomization

As previously described with our preliminary data [

6], this is a phase 2, randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled trial to compare the impact of infusions of

A. satureioides inflorescences with dehydrated apple tea infusion,

Malus domestica. It was used apple infusion as control, considering its polyphenol level [

24,

25]. It is necessary to clarify that it was impossible to design a blind study on

A. satureioides infusion (tea), because of its distinctive flavor.

Eligible patients were older than 18 years old and suffering with viral respiratory infection symptoms, such as fever, cough, and/or fatigue. Exclusion criteria were severe cases (need of hospitalization at the first medical care seeking) and

A. satureioides or apple intolerance for either sex; and women who are pregnant or with reproductive potential (without any contraceptive use). The participants asked for medical care at the Municipal Screening Unit (UMT) for COVID-19 in Igrejinha (29.5734° S, 50.7925° W) and the Primary Healthcare Units of “Grupo Hospitalar Conceição” of Porto Alegre (30.0100° S, 51.0928° W), all of them located in Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. The sample size determination required for the complete clinical trial was widely described [

6]. A total of 240 eligible patients were enrolled.

Eligible patients were invited and were verbally informed about the study. After understanding all the research information and agreement to participate, they read and signed an informed consent form. All efforts were undertaken to guarantee accurate results and to ensure integrity and confidentiality for the trial participants. The randomization was performed using the virtual platform [

6]. Packages containing the inflorescences or the dehydrated apples immediately after the randomization were available to participants.

4.3. Plant Material and Intervention

A. satureioides inflorescences and dehydrated apple (

M. domestica) were provided by the Kampo de Ervas in Turvo, Paraná, Brazil, with organic certification by ECOCERT

®. The access to genetic resources was recorded in the National System, SISGEN (A928BF2). The quality control, phytochemical and microbiological characterization, was previously described with our preliminary data [

6].

The participants were instructed on infusion preparation in accordance with the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia 6th edition, adding 1.5 g of the received plant material to 150 mL of boiling water with infusion for 15 minutes, and on infusion use pattern, twice a day for 2 weeks [

6].

4.4. Assessment

Sociodemographic and additional clinical characteristics, such as comorbid conditions, allergies and prescribed drugs, were collected with a 31-item questionnaire at the first medical care seeking (baseline). When nasopharyngeal swabs were used for the SARS-CoV-2 detection (RT-PCR). Vaccination status was reported by the participants and checked in their medical records. Signs and symptoms were collected at least once a day using a semi-structured 45-item questionnaire, available with remote monitoring approaches to be filled online (

https://forms.gle/u6agfX3UMtNQSfbw7), using an app, by telephone, or in paper. As well as the medical records were checked. Blood samples were collected before and after the intervention.

4.5. Endpoints

Our primary endpoint was the recovery time for respiratory symptoms (sore throat, dyspnea, sneezing and cough), defined as the duration (number of days) from randomization to the first day free of symptoms. Secondary outcomes were the recovery time for non-respiratory symptoms (fever, body ache, earache and loss of appetite) and recovery time for all the studied symptoms considering vaccination status against SARS-CoV-2 (vaccinated and non-vaccinated participants) and COVID-19 infection (SARS-CoV-2+ or SARS-CoV-2-). In addition, the rate of symptom recovery in the overall and stratified analysis on days 8 and 14 after enrollment, was also evaluated.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

We performed an overall analysis comparing all participants in the intervention group with the control group, and then stratified subgroup analysis, considering the adjusted analysis with COVID-19 infection (SARS-CoV-2+ or SARS-CoV-2-) and vaccination status against SARS-CoV-2 (vaccinated and non-vaccinated participants). After receiving the RT-PCR results, approximately 30% of the participants had COVID-19. In addition, considering

A. satureioides can act against different pathogens related to upper respiratory tract infections [

12,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], we evaluated the SARS-CoV-2-negative subgroup. The SARS-CoV2+ participants were also stratified according to their SARS-CoV2 vaccination status (vaccinated and non-vaccinated participants), since this is associated with severity and progression of COVID-19 symptoms [

20].

Our analysis followed a “per-protocol” principle (PP). Categorical variables were described as percentages, and continuous variables were described as mean (standard difference [SDs]) and median (interquartile range [IQR]). To investigate the primary outcome, the Log-Rank test was employed to compare the median survival time to symptom recovery between the groups. The log-rank test compares time to event endpoints, in our study the event was symptom recovery. Patients who did not recover were censored on day 14. The Cox regression was used to calculate Hazard Ratios (HR). The recovery rate is expressed as the percentage of participants self-reporting symptom absence on days 8th and 14th and compared between the group with the Chi-Square test. A 95% confidence interval and significance level of 0.05 were used. The software Rstudio version 4.2.2 was used.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that 14-day course A. satureioides inflorescence infusion twice a day may offer benefits in the management of mild viral respiratory infections symptoms, including those induced by COVID-19, because consistently improved the rate of symptom recovery and induced significantly faster recovery. Our findings may support the popular use of A. satureioides infusion as an adjuvant therapy for managing viral respiratory tract infections symptoms. Further investigation for clinical validation and to better understand the infusion mechanism of action are still needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Kaplan-Meier curves for time to recovery from (A) Dyspnea, (B) Cough, (C) Loss of appetide, (D) Earache and (E) Body ache in the overall analysis; Figure S2: Kaplan-Meier curves for time to recovery from (A) Dyspnea, (B) Sneezing, (C) Earache and (D) Loss of appetide in the non-vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup analysis; Figure S3: Kaplan-Meier curves for time to recovery from (A) Cough, (B) Fever, (C) Sore throat and (D) Body ache in the vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup analysis; Figure S4: Kaplan-Meier curves for time to recovery from cough for patients in the Malus domestica group. Non-vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive and vaccinated SARS-CoV2 positive subgroup analysis; Figure S5: Kaplan-Meier curves for time to recovery from (A) Dyspnea, (B) Cough, (C) Sneezing, (D) Fever and (E) Body ache in the SARS-CoV2 negative subgroup analysis.

Author Contributions

CIMB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LRC: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Investigation, Validation. AHSN: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation. FBR: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation. MLL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SEB: Methodology, Investigation, Validation. GM: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Validation. PVW Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Data Curation, Visualization. VLB: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. IRS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This work was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (number 88887.506777/2020–00) and by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) fellowships (Dr. I.R. Siqueira [grant number 308040/2022-8], Dr. V.L. Bassani, Dr. S.E. Bianchi, Dr. G. Meirelles, Dr. E.S. Loss, and Dr. M.L. Lamers).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge the institutional and staff support provided by the Primary Healthcare Units of “Jardim ITU”, “Nossa Senhora Aparecida” affiliated with “Grupo Hospitalar Conceição” of Porto Alegre, as well as the Municipal Screening Unit (UMT) for COVID-19 in the municipality of Igrejinha. The support and provision of resources throughout the course of this research provided by these institutions have played a crucial role in the successful completion of this study. Additionally, the authors extend the appreciation to all the participants of this trial, whose involvement was essential in advancing this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019

SARS-COV2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

A. satureioides Achyrocline satureioides

M. domestica, Malus domestica

NE Not possible to estimate

ReBEC Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trial

RT-PCR Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

UMT Municipal Screening Unit

SISGEN Sistema Nacional de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético e do Conhecimento Tradicional Associado

PP “per-protocol” principle

ACE2 Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

TMPRSS2 Transmembrane serine protease 2

3CLpro 3-chymotrypsin-like protease.

References

- Castro Braga, F. Brazilian Traditional Medicine: Historical Basis, Features and Potentialities for Pharmaceutical Development. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences 2021, 8, S44–S50. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, R.C.; Campos, M.M.; Santos, A.R.S.; Calixto, J.B. Medicinal Plants in Brazil: Pharmacological Studies, Drug Discovery, Challenges and Perspectives. Pharmacol Res 2016, 112, 4–29. [CrossRef]

- Ballabh, B.; Chaurasia, O.P. Traditional Medicinal Plants of Cold Desert Ladakh--Used in Treatment of Cold, Cough and Fever. J Ethnopharmacol 2007, 112, 341–349. [CrossRef]

- Retta, D.; Dellacassa, E.; Villamil, J.; Suárez, S.A.; Bandoni, A.L. Marcela, a Promising Medicinal and Aromatic Plant from Latin America: A Review. Industrial Crops and Products 2012, 38, 27–38. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.R.; Simões, C.M.O.; Bassani, V.L. Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) D.C. as a Potential Approach for Management of Viral Respiratory Infections. Phytother Res 2021, 35, 3–5. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, C.I.M.; Dani, C.; Cechinel, L.R.; da Silva Neves, A.H.; Rasia, F.B.; Bianchi, S.E.; da Silveira Loss, E.; Lamers, M.L.; Meirelles, G.; Bassani, V.L.; et al. Achyrocline satureioides as an Adjuvant Therapy for the Management of Mild Viral Respiratory Infections in the Context of COVID-19: Preliminary Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, and Open-Label Clinical Trial. Phytother Res 2023, 37, 5354–5365. [CrossRef]

- Kenealy, T. Sore Throat. BMJ Clin Evid 2014, 2014, 1509.

- Hu, K.; Guan, W.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Q.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Duan, Z.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lianhuaqingwen Capsules, a Repurposed Chinese Herb, in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153242. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, C.-S.; Zhang, C.; Tang, G.-Y.; Tan, H.-Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Wang, N.; Lai, A.Y.-K.; Feng, Y. Edible and Herbal Plants for the Prevention and Management of COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 656103. [CrossRef]

- Barioni, E.D.; Santin, J.R.; Machado, I.D.; Rodrigues, S.F. de P.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Wagner, T.M.; Cogliati, B.; Corrêa dos Santos, M.; Machado, M. da S.; Andrade, S.F. de; et al. Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) D.C. Hydroalcoholic Extract Inhibits Neutrophil Functions Related to Innate Host Defense. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 2013, 787916. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, K.C.B.; Bassani, V.L.; Schapoval, E.E.S. Influence of Excipients and Technological Process on Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Quercetin and Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) D.C. Extracts by Oral Route. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 102–108. [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, F.; Khan, A.; Iqtadar, S.; Mumtaz, S.U.; Chaudhry, M.N.A.; Bertuccioli, A.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Togni, S.; Riva, A.; et al. Quercetin as a Possible Complementary Agent for Early-Stage COVID-19: Concluding Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 1096853. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Araújo, N.P.; de Matos, N.A.; Leticia Antunes Mota, S.; Farias de Souza, A.B.; Dantas Cangussú, S.; Cunha Alvim de Menezes, R.; Silva Bezerra, F. Quercetin Attenuates Acute Lung Injury Caused by Cigarette Smoke Both In Vitro and In Vivo. COPD 2020, 17, 205–214. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.A.; Emala, C.W. Quercetin Acutely Relaxes Airway Smooth Muscle and Potentiates β-Agonist-Induced Relaxation via Dual Phosphodiesterase Inhibition of PLCβ and PDE4. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2013, 305, L396-403. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, R.; Li, X.; He, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Quercetin as an Antiviral Agent Inhibits Influenza A Virus (IAV) Entry. Viruses 2015, 8, 6. [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Lysiuk, R.; Shanaida, M.; Peana, M.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Beley, N.; Kovalska, N.; Bjørklund, G. Quercetin in the Prevention and Treatment of Coronavirus Infections: A Focus on SARS-CoV-2. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1049. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.V.; Chan, M.; Banadyga, L.; He, S.; Zhu, W.; Chrétien, M.; Mbikay, M. Quercetin Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Prevents Syncytium Formation by Cells Co-Expressing the Viral Spike Protein and Human ACE2. Virol J 2024, 21, 29. [CrossRef]

- Manjunathan, R.; Periyaswami, V.; Mitra, K.; Rosita, A.S.; Pandya, M.; Selvaraj, J.; Ravi, L.; Devarajan, N.; Doble, M. Molecular Docking Analysis Reveals the Functional Inhibitory Effect of Genistein and Quercetin on TMPRSS2: SARS-COV-2 Cell Entry Facilitator Spike Protein. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 180. [CrossRef]

- Yakoot, M. Nonsignificant Trends in COVID-19 Trials: Is There a Significance? J Med Virol 2022, 94, 1757–1760. [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Teo, S.P.; Abdullah, M.S.; Chong, P.L.; Asli, R.; Mani, B.I.; Momin, N.R.; Lim, A.C.A.; Rahman, N.A.; Chong, C.F.; et al. COVID-19 Symptom Duration: Associations with Age, Severity and Vaccination Status in Brunei Darussalam, 2021. WPSAR 2022, 13, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, M.; Wei, G.-W. Mutations Strengthened SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity. Journal of Molecular Biology 2020, 432, 5212–5226. [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Tzou, P.L.; Nouhin, J.; Gupta, R.K.; De Oliveira, T.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Fera, D.; Shafer, R.W. The Biological and Clinical Significance of Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Nat Rev Genet 2021, 22, 757–773. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Barbosa, A.N.; Cimerman, S. Editorial: New Therapeutic Approaches for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1276279. [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.; Melo, E.; Lima, D. Teor de Compostos Fenolicos Totais Em Chás Brasileiros. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology 2004, 7, 187–190.

- Balsan, G.; Pellanda, L.C.; Sausen, G.; Galarraga, T.; Zaffari, D.; Pontin, B.; Portal, V.L. Effect of Yerba Mate and Green Tea on Paraoxonase and Leptin Levels in Patients Affected by Overweight or Obesity and Dyslipidemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutr J 2019, 18, 5. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Luo, C.; Liu, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, G.; Liew, O.W.; Zhu, W.; Puah, C.M.; Shen, X.; et al. Binding Interaction of Quercetin-3-β-Galactoside and Its Synthetic Derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CLpro: Structure–Activity Relationship Studies Reveal Salient Pharmacophore Features. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 14, 8295–8306. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Murphy, E.A.; McClellan, J.L.; Carmichael, M.D.; Gangemi, J.D. Quercetin Reduces Susceptibility to Influenza Infection Following Stressful Exercise. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2008, 295, R505–R509. [CrossRef]

- Farazuddin, M.; Mishra, R.; Jing, Y.; Srivastava, V.; Comstock, A.T.; Sajjan, U.S. Quercetin Prevents Rhinovirus-Induced Progression of Lung Disease in Mice with COPD Phenotype. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199612. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Faris, A.N.; Comstock, A.T.; Wang, Q.; Nanua, S.; Hershenson, M.B.; Sajjan, U.S. Quercetin Inhibits Rhinovirus Replication in Vitro and in Vivo. Antiviral Research 2012, 94, 258–271. [CrossRef]

- Uchide, N.; Toyoda, H. Antioxidant Therapy as a Potential Approach to Severe Influenza-Associated Complications. Molecules 2011, 16, 2032–2052. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).