Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.3. Plasmid and Short interfering RNA (siRNA) Transfection

2.4. Immunoprecipitation (IP)

2.5. Western Blotting

2.5. GEF-H1 and RhoA Activation Assay

2.5. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

2.8. Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA):

2.8. RT2 Profiler Fibrosis Array

2.8. RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

2.8. Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction (UUO) Mouse Model

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

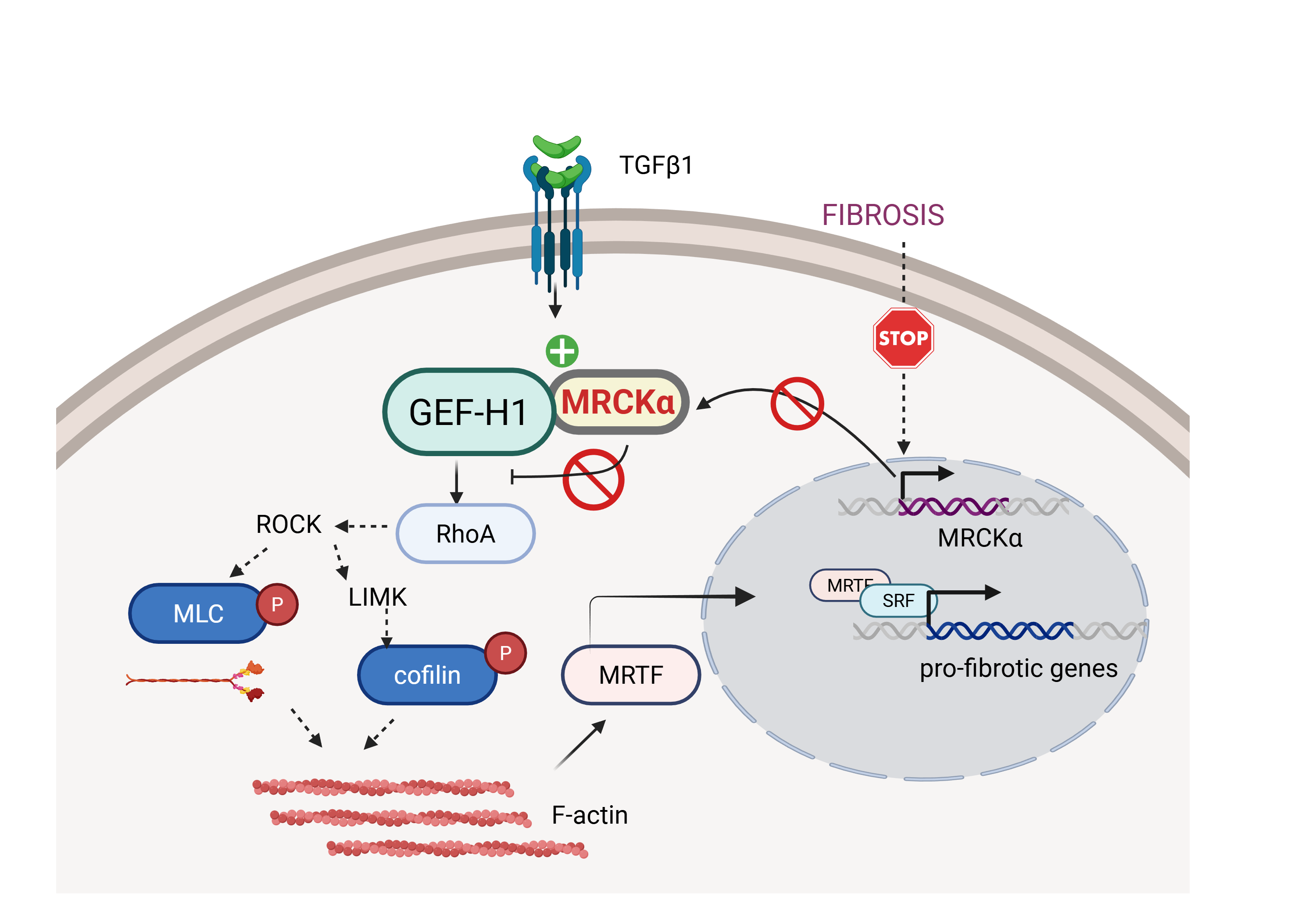

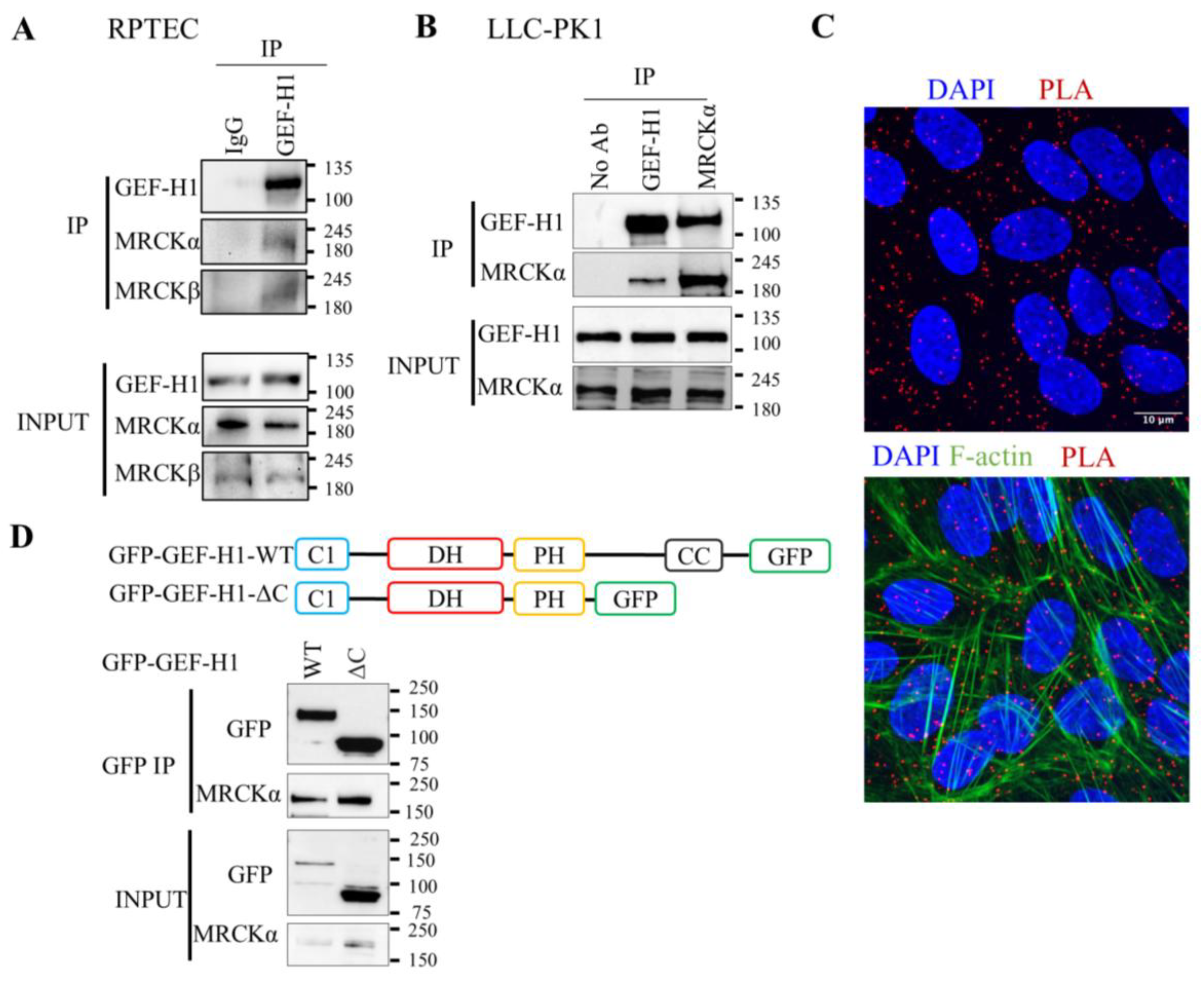

3.1. Association Between MRCKα and the N-Terminus of GEF-H1

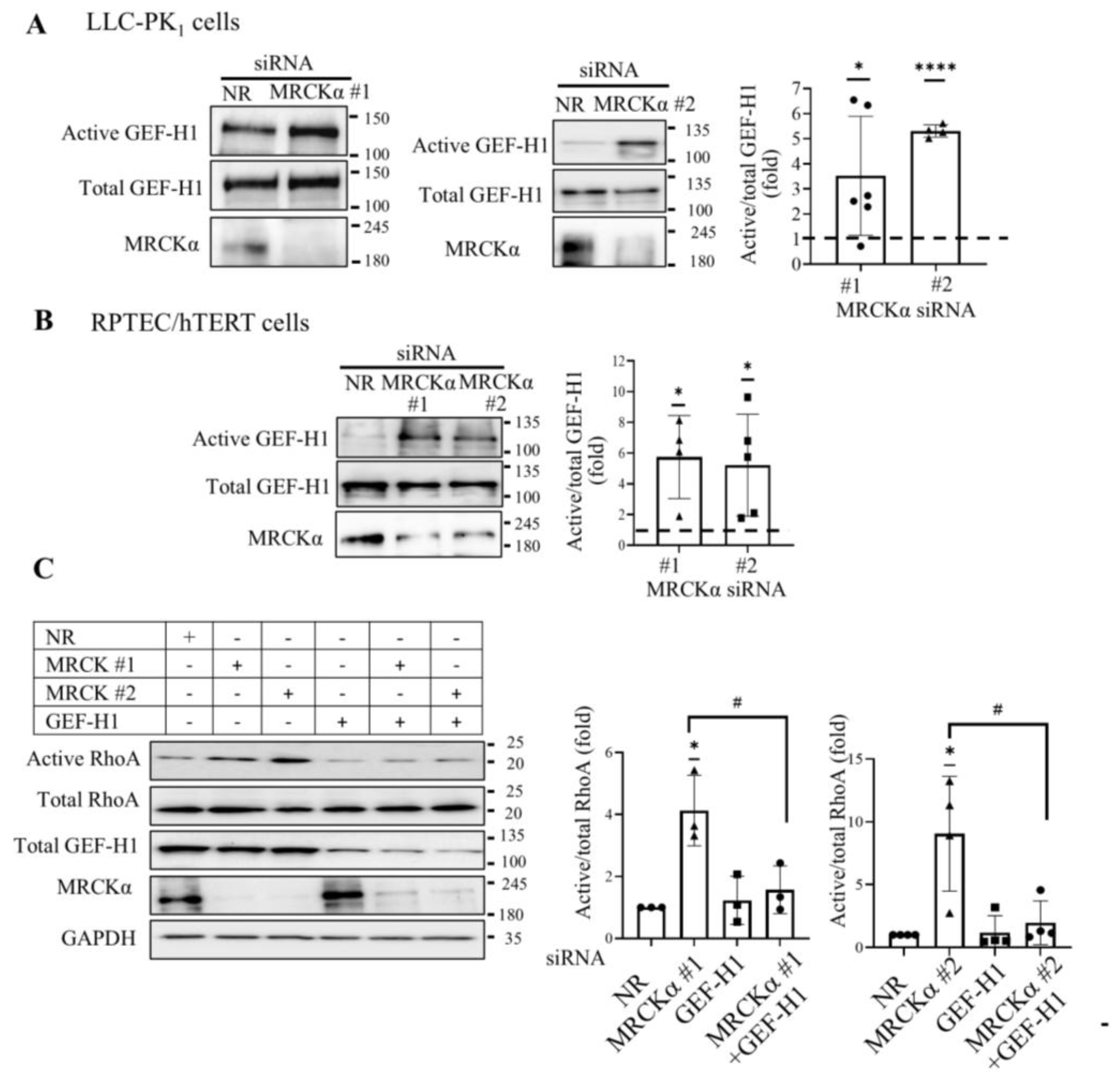

3.2. MRCKα Inhibits GEF-H1-Mediated RhoA Activation

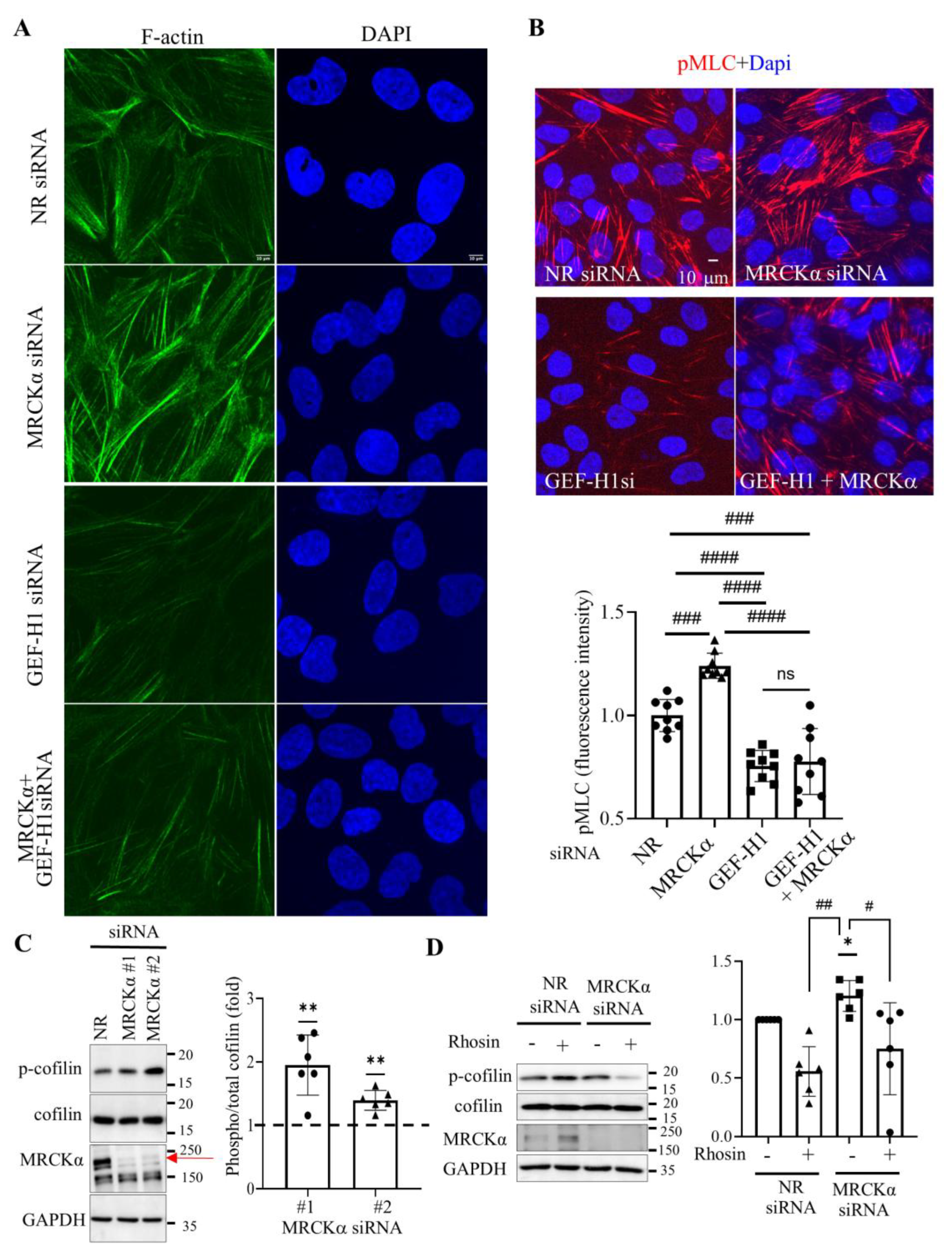

3.3. MRCKα Silencing Augments GEF-H1 Dependent Stress Fiber Formation and MLC phosphorylation, and RhoA-Dependent Cofilin Phosphorylation

3.4. MRCKα Exerts a Negative Feed-Back on GEF-H1 Activation

3.5. MRCKα Silencing Elevates Expression of Fibrosis-Related Genes

3.6. MRCKα Silencing Promotes MRTF-Dependent Gene Transcription

3.7. MRCKα Expression Is Reduced in a Mouse Kidney Fibrosis Model.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Ethical Approval

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor |

| CCN2 | Cellular Communication Network Factor 2 |

| GEF | Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| LIMK | LIM domain kinase |

| MRCK | Myotonic Dystrophy Kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase |

| MRTF | Myocardin-Related Transcription Factor |

| NR | non-related |

| PLA | Proximity Ligation Assay |

| SMA | Smooth muscle actin |

| TGFβ1 | Transforming Growth Factor β1 |

References

- Panizo, S.; Martinez-Arias, L.; Alonso-Montes, C.; Cannata, P.; Martin-Carro, B.; Fernandez-Martin, J.L.; Naves-Diaz, M.; Carrillo-Lopez, N.; Cannata-Andia, J.B. Fibrosis in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathogenesis and Consequences. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammirati, A.L. Chronic Kidney Disease. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2020(66) Suppl 1, s03–s09. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Fu, P.; Ma, L. Kidney fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Fu, H.; Liu, Y. The fibrogenic niche in kidney fibrosis: components and mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiessl, I.M. The Role of Tubule-Interstitial Crosstalk in Renal Injury and Recovery. Semin Nephrol 2020, 40, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialik, J.F.; Ding, M.; Speight, P.; Dan, Q.; Miranda, M.Z.; Di Ciano-Oliveira, C.; Kofler, M.M.; Rotstein, O.D.; Pedersen, S.F.; Szaszi, K.; et al. Profibrotic epithelial phenotype: a central role for MRTF and TAZ. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.L.; Cantley, L.G. Adding insult to injury: the spectrum of tubulointerstitial responses in acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Li, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, B.; Lv, L.L.; Liu, B.C. Renal tubular epithelial cells response to injury in acute kidney injury. EBioMedicine 2024, 107, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaggin, S.E.; Kapus, A. Scar wars: mapping the fate of epithelial-mesenchymal-myofibroblast transition. Kidney Int 2011, 80, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Tumarin, J.; Prabhakar, S. Cellular cross-talk drives mesenchymal transdifferentiation in diabetic kidney disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1499473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, E.H.; Schaub, J.R.; Decaris, M.; Turner, S.; Derynck, R. TGF-beta as a driver of fibrosis: physiological roles and therapeutic opportunities. J Pathol 2021, 254, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, S.; Dan, Q.; Sri Theivakadadcham, V.S.; Wu, B.; Kofler, M.; Layne, M.D.; Connelly, K.A.; Rzepka, M.F.; Friedberg, M.K.; Kapus, A.; et al. Regulation of the RhoA exchange factor GEF-H1 by profibrotic stimuli through a positive feedback loop involving RhoA, MRTF, and Sp1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2024, 327, C387–C402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Rabani, R.; Venugopal, S.; Xiao, J.; Anwer, S.; Ding, M.; Speight, P.; Pan, W.; Alexander, R.T.; et al. Claudin-2 suppresses GEF-H1, RHOA, and MRTF thereby impacting proliferation and profibrotic phenotype of tubular cells. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 15446–15465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Sebe, A.; Peterfi, Z.; Masszi, A.; Thirone, A.C.; Rotstein, O.D.; Nakano, H.; McCulloch, C.A.; Szaszi, K.; Mucsi, I.; et al. Cell contact-dependent regulation of epithelial-myofibroblast transition via the rho-rho kinase-phospho-myosin pathway. Mol Biol Cell 2007, 18, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakiashvili, E.; Speight, P.; Waheed, F.; Seth, R.; Lodyga, M.; Tanimura, S.; Kohno, M.; Rotstein, O.D.; Kapus, A.; Szaszi, K. GEF-H1 Mediates Tumor Necrosis Factor-{alpha}-induced Rho Activation and Myosin Phosphorylation: role in the regulation of tubular paracellular permeability. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 11454–11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.Z.; Lichner, Z.; Szaszi, K.; Kapus, A. MRTF: Basic Biology and Role in Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.M. The actin-MRTF-SRF gene regulatory axis and myofibroblast differentiation. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2012, 5, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, G.; Streb, J.W.; Long, X.; Yang, Y.; Stoeckert, C.J., Jr.; Miano, J.M. Defining the mammalian CArGome. Genome Res 2006, 16, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichner, Z.; Ding, M.; Khare, T.; Dan, Q.; Benitez, R.; Praszner, M.; Song, X.; Saleeb, R.; Hinz, B.; Pei, Y.; et al. Myocardin-Related Transcription Factor Mediates Epithelial Fibrogenesis in Polycystic Kidney Disease. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, R.; Baradaran, B.; Khordadmehr, M.; Safaei, S.; Baghbanzadeh, A.; Jigari, F.; Ezzati, H. Targeting ROCK signaling in health, malignant and non-malignant diseases. Immunol Lett 2020, 219, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaddeghzadeh, N.; Ahmadian, M.R. The RHO Family GTPases: Mechanisms of Regulation and Signaling. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfils, J.; Zeghouf, M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev 2013, 93, 269–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.; Olson, M.F. Regulation and functions of the RhoA regulatory guanine nucleotide exchange factor GEF-H1. Small GTPases 2021, 12, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkenfeld, J.; Nalbant, P.; Yoon, S.H.; Bokoch, G.M. Cellular functions of GEF-H1, a microtubule-regulated Rho-GEF: is altered GEF-H1 activity a crucial determinant of disease pathogenesis? Trends Cell Biol 2008, 18, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Lai, J.; Chen, H.; Cai, Y.; Yue, Z.; Lin, H.; Sun, L. Reducing GEF-H1 Expression Inhibits Renal Cyst Formation, Inflammation, and Fibrosis via RhoA Signaling in Nephronophthisis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.; Hemkemeyer, S.A.; Alimajstorovic, Z.; Bowers, C.; Eskandarpour, M.; Greenwood, J.; Calder, V.; Chan, A.W.E.; Gane, P.J.; Selwood, D.L.; et al. Therapeutic Validation of GEF-H1 Using a De Novo Designed Inhibitor in Models of Retinal Disease. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numaga-Tomita, T.; Kitajima, N.; Kuroda, T.; Nishimura, A.; Miyano, K.; Yasuda, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Sato, Y.; Ide, T.; Birnbaumer, L.; et al. TRPC3-GEF-H1 axis mediates pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 39383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapara, A.; Luthert, P.; Greenwood, J.; Hill, C.S.; Matter, K.; Balda, M.S. The RhoA activator GEF-H1/Lfc is a transforming growth factor-beta target gene and effector that regulates alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and cell migration. Mol Biol Cell 2010, 21, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krendel, M.; Zenke, F.T.; Bokoch, G.M. Nucleotide exchange factor GEF-H1 mediates cross-talk between microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. Nat Cell Biol 2002, 4, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, S.; D'Atri, F.; Citi, S.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. Binding of GEF-H1 to the tight junction-associated adaptor cingulin results in inhibition of Rho signaling and G1/S phase transition. Dev Cell 2005, 8, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenke, F.T.; Krendel, M.; DerMardirossian, C.; King, C.C.; Bohl, B.P.; Bokoch, G.M. p21-activated kinase 1 phosphorylates and regulates 14-3-3 binding to GEF-H1, a microtubule-localized Rho exchange factor. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 18392–18400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Miki, H. Dynamic regulation of GEF-H1 localization at microtubules by Par1b/MARK2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 408, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheed, F.; Dan, Q.; Amoozadeh, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tanimura, S.; Speight, P.; Kapus, A.; Szaszi, K. Central role of the exchange factor GEF-H1 in TNF-alpha-induced sequential activation of Rac, ADAM17/TACE, and RhoA in tubular epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 2013, 24, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birukova, A.A.; Fu, P.; Xing, J.; Yakubov, B.; Cokic, I.; Birukov, K.G. Mechanotransduction by GEF-H1 as a novel mechanism of ventilator-induced vascular endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010, 298, L837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilluy, C.; Swaminathan, V.; Garcia-Mata, R.; O'Brien, E.T.; Superfine, R.; Burridge, K. The Rho GEFs LARG and GEF-H1 regulate the mechanical response to force on integrins. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, V.P.; Hengst, J.A.; Desai, D.H.; Amin, S.G.; Yun, J.K. The regulatory roles of ROCK and MRCK kinases in the plasticity of cancer cell migration. Cancer Lett 2015, 361, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Manser, E. Myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinases (MRCK), the ROCK-like effectors of Cdc42 and Rac1. Small GTPases 2015, 6, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihni, C. MRCK: a master regulator of tissue remodeling or another 'ROCK' in the epithelial block? Tissue Barriers 2021, 9, 1916380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unbekandt, M.; Olson, M.F. The actin-myosin regulatory MRCK kinases: regulation, biological functions and associations with human cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014, 92, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozadeh, Y.; Anwer, S.; Dan, Q.; Venugopal, S.; Shi, Y.; Branchard, E.; Liedtke, E.; Ailenberg, M.; Rotstein, O.D.; Kapus, A.; et al. Cell confluence regulates claudin-2 expression: possible role for ZO-1 and Rac. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2018, 314, C366–C378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, S.H.; Tanimura, S.; Mure, S.; Kashimoto, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Kohno, M. ERK1/2 phosphorylate GEF-H1 to enhance its guanine nucleotide exchange activity toward RhoA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 368, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, F.; Speight, P.; Dan, Q.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Szaszi, K. Affinity precipitation of active Rho-GEFs using a GST-tagged mutant Rho protein (GST-RhoA(G17A)) from epithelial cell lysates. J Vis Exp 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Mata, R.; Wennerberg, K.; Arthur, W.T.; Noren, N.K.; Ellerbroek, S.M.; Burridge, K. Analysis of activated GAPs and GEFs in cell lysates. Methods Enzymol 2006, 406, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, T.; Chen, X.Q.; Tan, I.; Manser, E.; Lim, L. Myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase acts as a Cdc42 effector in promoting cytoskeletal reorganization. Mol Cell Biol 1998, 18, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, M.; Nakayama, M.; Kaibuchi, K. Rho-kinase/ROCK: A key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011, 67, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Shibuya, A.; Nakamura, T. Activation of LIM kinases by myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase alpha. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 23092–23096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masszi, A.; Di Ciano, C.; Sirokmany, G.; Arthur, W.T.; Rotstein, O.D.; Wang, J.; McCulloch, C.A.; Rosivall, L.; Mucsi, I.; Kapus, A. Central role for Rho in TGF-beta1-induced alpha-smooth muscle actin expression during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2003, 284, F911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi, F.S.; Son, D.O.; Firmino, J.; Hinz, B. Myofibroblast Markers and Microscopy Detection Methods in Cell Culture and Histology. Methods Mol Biol 2021, 2299, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masszi, A.; Speight, P.; Charbonney, E.; Lodyga, M.; Nakano, H.; Szaszi, K.; Kapus, A. Fate-determining mechanisms in epithelial-myofibroblast transition: major inhibitory role for Smad3. J Cell Biol 2010, 188, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Klimova, E.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E.; Tapia, E.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction as a Model to Investigate Fibrosis-Attenuating Treatments. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Yamashita, Y.I.; Umezaki, N.; Okamoto, Y.; Ogata, Y.; Yasuda-Yoshihara, N.; Itoyama, R.; Yusa, T.; Yamashita, K.; et al. High ARHGEF2 (GEF-H1) Expression is Associated with Poor Prognosis Via Cell Cycle Regulation in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieb, W.S.; Lungu, C.; Tamas, R.; Berreth, H.; Rathert, P.; Storz, P.; Olayioye, M.A.; Hausser, A. The GEF-H1/PKD3 signaling pathway promotes the maintenance of triple-negative breast cancer stem cells. Int J Cancer 2020, 146, 3423–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Yang, T.; Tang, D.; Zhou, F.; Qian, Y.; Zou, X. Increased expression of GEF-H1 promotes colon cancer progression by RhoA signaling. Pathol Res Pract 2019, 215, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, O.A.; Sandi, M.J.; Rottapel, R. Co-dependency between KRAS addiction and ARHGEF2 promotes an adaptive escape from MAPK pathway inhibition. Small GTPases 2019, 10, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Guo, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, Q.; Chang, P.; Tao, K. Guanine nucleotide exchange factor H1 can be a new biomarker of melanoma. Biologics 2016, 10, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemot, L.; Paschoud, S.; Jond, L.; Foglia, A.; Citi, S. Paracingulin regulates the activity of Rac1 and RhoA GTPases by recruiting Tiam1 and GEF-H1 to epithelial junctions. Mol Biol Cell 2008, 19, 4442–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-Sandino, A.; Castillo-Kauil, A.; Dominguez-Calderon, A.; Alarcon, L.; Flores-Benitez, D.; Cuellar-Perez, F.; Lopez-Bayghen, B.; Chavez-Munguia, B.; Vazquez-Prado, J.; Gonzalez-Mariscal, L. Zonula occludens-2 regulates Rho proteins activity and the development of epithelial cytoarchitecture and barrier function. Biochim Biophys Acta 2017, 1864, 1714–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoitei, M.L.; Noh, J.; Marston, D.J.; Roudot, P.; Marshall, C.B.; Daugird, T.A.; Lisanza, S.L.; Sandi, M.J.; Ikura, M.; Sondek, J.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of GEF-H1 activation controlled by microtubule- and Src-mediated pathways. J Cell Biol 2019, 218, 3077–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, M.G.; Zozulya, S.; Gishizky, M.L.; Jallal, B.; Smeal, T. PAK4 mediates morphological changes through the regulation of GEF-H1. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiri, D.; Greeve, M.A.; Brunet, A.; Finan, D.; Wells, C.D.; LaRose, J.; Rottapel, R. Modulation of Rho guanine exchange factor Lfc activity by protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 5963–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamahashi, Y.; Saito, Y.; Murata-Kamiya, N.; Hatakeyama, M. Polarity-regulating Kinase Partitioning-defective 1b (PAR1b) Phosphorylates Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor H1 (GEF-H1) to Regulate RhoA-dependent Actin Cytoskeletal Reorganization. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 44576–44584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkenfeld, J.; Nalbant, P.; Bohl, B.P.; Pertz, O.; Hahn, K.M.; Bokoch, G.M. GEF-H1 modulates localized RhoA activation during cytokinesis under the control of mitotic kinases. Dev Cell 2007, 12, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlaire, S.; Dehio, C. Bartonella effector protein C mediates actin stress fiber formation via recruitment of GEF-H1 to the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1008548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.; Seow, K.T.; Lim, L.; Leung, T. Intermolecular and intramolecular interactions regulate catalytic activity of myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase alpha. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21, 2767–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.; Yong, J.; Dong, J.M.; Lim, L.; Leung, T. A tripartite complex containing MRCK modulates lamellar actomyosin retrograde flow. Cell 2008, 135, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihni, C.; Terry, S.J. RhoGTPase signalling at epithelial tight junctions: Bridging the GAP between polarity and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2015, 64, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.C.J.; Leung, T.; Tan, I. Adaptor protein LRAP25 mediates myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase (MRCK) regulation of LIMK1 protein in lamellipodial F-actin dynamics. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 26989–27003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.; Lai, J.; Yong, J.; Li, S.F.; Leung, T. Chelerythrine perturbs lamellar actomyosin filaments by selective inhibition of myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase. FEBS Lett 2011, 585, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Paterson, H.F.; Marshall, C.J. Cdc42-MRCK and Rho-ROCK signalling cooperate in myosin phosphorylation and cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol 2005, 7, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunier, C.; Prudent, R.; Kapur, R.; Sadoul, K.; Lafanechere, L. LIM kinases: cofilin and beyond. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41749–41763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwa, M.Q.; Brandao, R.; Phung, T.H.; Ge, J.; Scieri, G.; Brakebusch, C. MRCKalpha Is Dispensable for Breast Cancer Development in the MMTV-PyMT Model. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, C.C.; Tang, J.; Costello, A.; Khakoo, N.S.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Goldschmeding, R.; Higgins, P.J.; Samarakoon, R. Negative regulators of TGF-beta1 signaling in renal fibrosis; pathological mechanisms and novel therapeutic opportunities. Clin Sci (Lond) 2021, 135, 275–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | siRNA sequence |

| Porcine MRCKα #1 | GGG AAA UGA AGA AGG GUU AUU |

| Porcine MRCKα #2 | AGU UAG AAG AAG AGG UAA AUU |

| Porcine MRTF-A | CCA AGG AGC UGA AGC CAA A |

| Porcine MRTF-B | CGA CAA ACA CCG UAG CAA A |

| Porcine GEF-H1 | CAAGAGCAUCACAGCCAAG |

| Gene | sequence |

| CCN2/CTGF F | GTG AAG ACA TAC CGG GCT AAG |

| CCN2/ CTGF R | GAC ACT TGA ACT CCA CAG GAA |

| ACTA2 F | CGTCCTAGACATCAGGGGGT |

| ACTA2 R | GGGGCAACACGAAGCTCATT |

| PPIA F | CGG GTC CTG GCA TCT TGT |

| PPIA R | TGG CAG TGC AAA TGA AAA ACT G |

| Gene | sequence |

| CDC42BPA F | TCGAAGCAAACATGTCCGGA |

| CDC42BPA R | CGTCTCCACACTGAAGCACT |

| GAPDH F | CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG |

| GAPDH F | ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).