1. Introduction

In numerous signal processing applications, the characterization of a physical process via its power spectrum, or its amplitude and phase spectra, is of fundamental importance. Typically, the recorded signal is sampled at uniform intervals over a finite observation period and stored as discrete sampled data. Spectral analysis serves multiple purposes, including the identification of characteristic frequencies for process recognition, the selection or attenuation of specific spectral components, and the precise estimation of amplitude and phase at specified frequencies. Conventional approaches predominantly rely on the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) or its computationally efficient companion, the fast Fourier transform (FFT), both of which decompose the data into Fourier series coefficients, from which the power spectrum can be derived [

1,

2]. These transformations are inherently invertible, computationally efficient, and straightforward to implement. However, their applicability is constrained by the requirement of equidistant sampling, a limitation that poses challenges for data acquisition, in general. In practical applications, missing or corrupted data is often handled by substituting zero values, a common but problematic approach. In contrast to the intension, zero values provide some sort of information and do not mean “not aquired”. Subsequently, this procedure introduces a systematic error that leads to increased inaccuracies in frequency and amplitude estimation and ultimately affects the reliability of parameter estimation. While the DFT naturally extends to higher dimensions, facilitating applications such as image reconstruction in magnetic resonance imaging [

3], image filtering [

4], and higher-order spectral filtering in spatiotemporal domains [

5], its performance deteriorates in the presence of non-uniform sampling. In ultrafast nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, non-uniform sampling enables substantial acceleration of chemical analysis [

6,

7], albeit at the cost of increased missing data, reduced sensitivity, and signal attenuation. These limitations are inherent to DFT-based and similar techniques, as they exhibit reduced accuracy when applied to incomplete datasets with data gaps [

8]. Although alternative methods, such as the "non-uniform Fourier transform" [

9,

10,

11], attempt to address these issues, they remain reliant on classical orthogonal mode decomposition (e. g., FFT, DFT, wavelet transform) and thus inherit systematic errors, as discussed in

Section 2.2.

The application of techniques based on Fourier series to signals with non-equidistant sampling is difficult, since it usually requires zero padding (replacing missing values by zeros) on a grid and in the general case resampling or interpolation of the data to a regular grid [

12,

13]. The effect of a gap filling method is investigated extensively by Munteanu et al. [

8]. The conclusion of the latter study is that without a corrective measure, errors such as amplitude minimization, which depends on the total gap density, cannot be avoided when FFT or DFT is applied. On the other hand, interpolation could be utilized to shift non-uniformly sampled data to a regular grid, so that the new interpolated data points are composed of the signal information and a projection of the accompanying noise. In the general case such distortions or noise are not band limited leading to biased estimates which consist of the local and aliased errors (noise, outliers, missing values, etc.) of the surrounding data.

Usually, astrophysical data is often affected by gaps, missing values and unevenly sampling. For example, when ground based radio telescopes are exploring areas in space there might exist time intervals in which the antenna is not pointing towards the object of interest due to the rotation of the Earth. The result is an incomplete data set. Non-uniform (random) sampling emerges for example if the irregular appearance of objects like Sunspots is measured as a binary quality depending on time and location.

Section 5.3 provides a working example which analyzes frequencies and periods in latitude and time from the two dimensional data set of Sunspot observations. An other technical example for random sampling (with highly variable sampling frequency) is asynchronous data acquisition in large sensor networks, which are used in Smart Home, Industry 4.0 and automated driving, see Geneva et al. [

14], Cadena et al. [

15], Sudars [

16]. Here the time series provide missing values and data gaps originating from time periods, in which strong noise prevents the measurement or simply the source of the signal to be measured is not in the range of the sensor.

The Lomb-Scargle method (LSM) was developed especially for ground based non-uniformly sampled one dimensional data, from which the amplitude spectrum is calculated [

17,

18]. The main advantage of this method is to directly estimate the spectrum without iterative optimization of trigonometric models as discussed in

Section 2.1. A fast version for one dimensional signals is presented by Townsend [

19] and Leroy [

20].

An extension of LSM to two- or three-dimensional time series have not been presented yet. Especially for large multivariate data sets such a direct approach would be comparably faster than present iterative procedures as proposed in (Babu and Stoica [

21], Chap. 9). The advantages of multivariate LSM will be demonstrated in

Section 5 by means of a 3D Ultrasound flow profile measurement and the 2D analysis of Sunspot time series data.

In case of the analysis of flow profile measurements which are obtained in an experiment investigating the magnetorotational instability in liquid metals [

22], such method would be highly desirable. Due to the complex experimental setup and the weak signal to noise ratio, the flow profile measurements contain several time intervals, in which distortions are dominant, see Seilmayer et al. [

23]. These time intervals had to be rejected leading to a time series with invalid (missing) data points, from which the multivariate version of LSM is able to determine the parameters of the characteristic traveling wave.

In order to demonstrate the method and to motivate the basic idea of the multivariate version of LSM we compare it, in terms of necessary conditions and error (noise) behaviour, with the traditional orthogonal mode decomposition (OMD) with trigonometric basis functions, which is the essence of the classical Fourier transform. It will be shown that LSM fits better to the conditions of an arbitrary finite length of the sampling series in comparison to DFT, because LSM reduces the error in model parameter estimation. In contrast to the traditional approach, which was derived from a statistical point of view (see the appendix of Scargle [

18]), the presented method is deduced from a technical point of view and focuses on its application. This leads to a slight change in the scaling of model parameters, which will be discussed in

Section 4.2. However, the introduced procedure includes all benefits, like arbitrary sampling, fragmented data and a good noise rejection.

The starting point of this paper is the analysis of a continuous 1D signal

which is composed of an arbitrary and finite set of individual frequency components

. Without loss of generality, band limitation is assumed stating that there exists an upper maximum frequency

with

, which mimics an intrinsic low pass filter characteristic of the measurement device. Since the measurement time is finite, the value of

s is only known in the time interval

with

and

. The

m-dimensional extension of this signal is

. If such a continuous signal is sampled, the pair

represents the measured 1D value and the corresponding instant in time whereas the pair

represents a measured value and the

m-dimensional location (

space/time) for the

i-th sample (

N is the number of samples). All the methods presented in this paper are implemented in a package written in R and published on CRAN [

24]. The reader will find more elaborate examples in the package and in the supplementary material.

2. Mathematical Model and Comparison of OMD and LSM

In order to delineate the differences between trigonometric OMD and LSM, we start with the basic model of a periodic signal as a sum of signals of different frequencies

with the corresponding amplitude

and phase shift

. The corresponding trigonometric model function

describes an infinite, stationary and steady process

with the coefficients

for the defined frequency

and the identities

as well as

. Furthermore, the trigonometric model above consists of an arbitrary number

of frequency components. If the given signal

is described by the defined model from Equation (

1) the model misfit

is given by

Thus, the signal can now be described by inserting Equation (

1) into Equation (

2) and defining the misfit

for each discrete frequency

k with

as follows:

The defined misfit originates form measurement uncertainties or parametric errors from , . In the general case can be any function or distribution. The challenge is to precisely determine the model parameters and for a given signal achieving minimal . This can be accomplished by one of the three methods described in the following sections: (i) Least-Square fit; (ii) orthogonal mode decomposition; (iii) Lomb-Scargle method (LSM).

2.1. Least Square Fit

The optimal fit is reached by least square fitting, resulting in a minimum

, which was shown by Barning [

25], Mathias et al. [

26]. Since such procedures are iterative, the convergence of the algorithm might need a large number of function evaluations of Equation (

3). Therefore, a direct version like LSM is preferable. It can be shown that LSM becomes equivalent to a least square fit of a sinusoidal model [

17,

25].

2.2. Trigonometric OMD

Generally, two functions

are said to be orthogonal on the interval

if the following condition holds, refer to Weisstein [

27]:

By selecting

and

, the integration leads, by exploiting the identity

, to

, which is only zero, if

This is true for any

, if the length of the interval

is a multiple of the period

so that

with

. It is interesting to note that this interval can be shorted to one half of the period, if

is zero. By exploiting this feature of the trigonometric functions, the individual model coefficients are calculated by multiplying the sine or the cosine to the measured data

and integrating over all times as shown by (Cohen [

1], Chap. 15):

For a measured signal, the integration can only be performed over the interval

. It is obvious that an error is introduced, if

. In order to investigate the properties of the finite integration, we will focus on the cosine term (Equation (

5)), since the analysis of the sine term (Equation (6)) is similar. By setting the integral boundaries to the finite time interval and expressing the signal using Equation (

3), the integral in Equation (

5) can be written as

Using the identities

and

, Equation (

7) becomes

The equation above indicates that the coefficient

is effected by two errors

(truncation) and

(random) which might be nonzero for an arbitrary

T. Thus, if both errors are neglected, the integral on the left hand side turns into an approximation of

. Taking the consideration about the orthogonality described in Equation (

4) into account,

becomes only zero, if the integration time

T is an integer multiple of

. This means for the Fourier series that a given integration time

T (observation window) defines the lowest allowed frequency

. Furthermore, only multiples of this fundamental frequency

with

are allowed in the Fourier series because

in this case.

The technical realization of OMD is called “quadrature demodulation”, which is the discrete version of equation (

8) by replacing the integral over

into a sum over the discrete sampled values

and setting the truncation error to zero. For a time discrete signal with

N samples and equidistant sampling with a constant sampling period

, and

, the parameter

(corresponding to the frequency

) is approximated by

According to the previous considerations, the truncation error

is larger than zero if the measurement range

is not exactly a multiple of

, as shown in

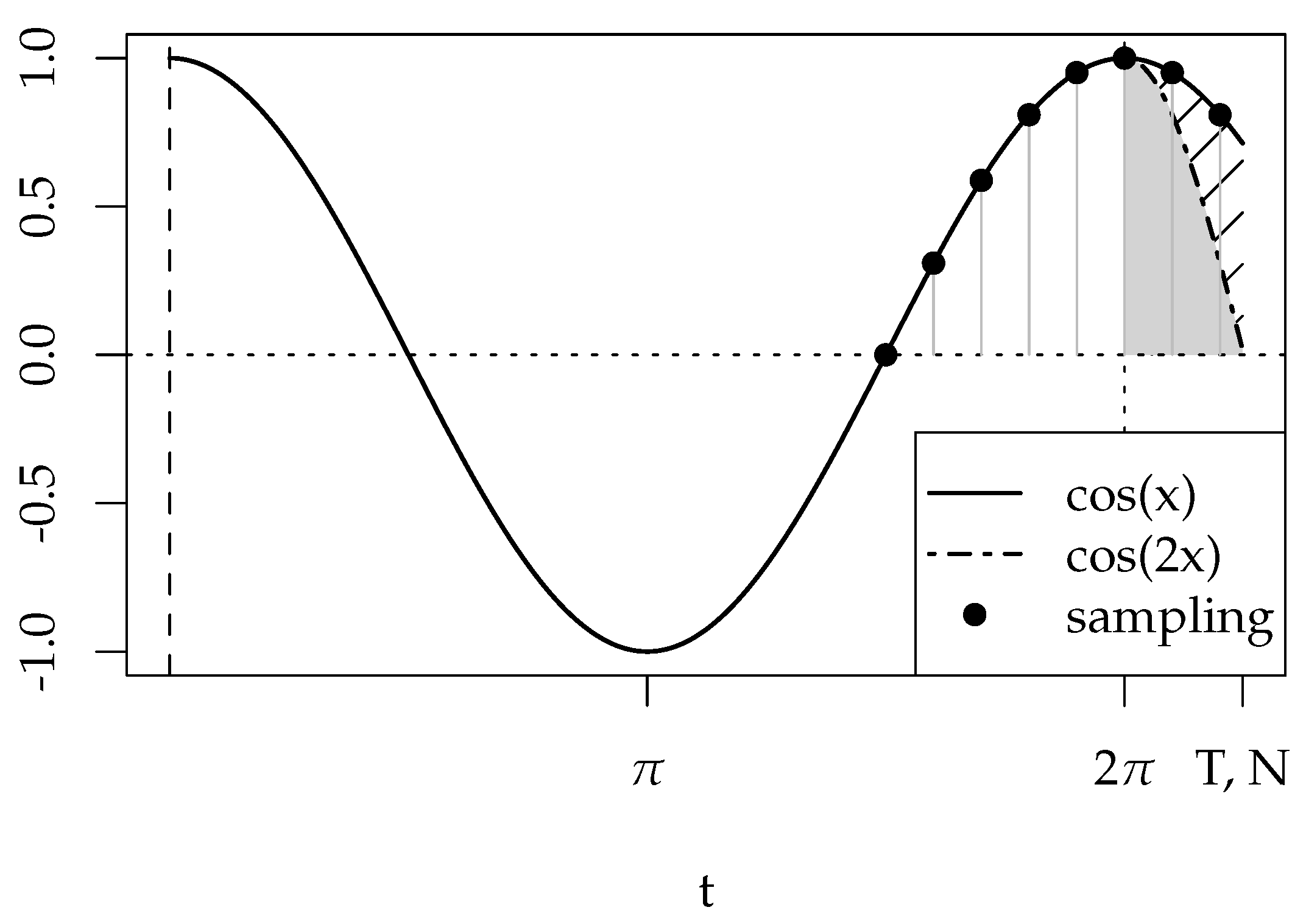

Figure 1.

In this example a signal with a time period of is sampled with , . The total integration time is , being slightly longer than the period of the signal, which is indicated by the two additional sampling points after . The truncation error equals the gray shaded area.

Generally speaking, the sampling error in the discrete version can be estimated by

where

,

. The random error is modeled by the

-quantile of the sampling error distribution

related to the underlying process with its standard deviation

(e. g. JCGM [

28]). This estimates the confidence interval of

and

, respectively (see supplementary material for details).

The above considerations lead to following four statements, which are derived in detail in

Section 2 of the supplementary material : (i) the maximum absolute value of the truncation error is bounded

if

, which is consistent with the experimental findings from Thompson and Tree [

29]; (ii)

is independent from the total number of samples

N for a constant time

T, which makes the OMD a non-consistent estimator for model parameters

and

; (iii) by increasing the sample rate, the random error decreases by

but scales with twice the standard deviation of noise distribution; (iv) DFT can be derived from Equation (

10) by restricting to equidistant sampling with constant

.

Concluding, the truncation error, which is an intrinsic feature of OMD, produces a systematic deviation from the true value depending on the difference between the sampling time interval and the corresponding period of the frequency of interest. In contrast to that, the random error diminishes with increasing sampling rate

. A detailed discussion on this topic can be found in Thompson and Tree [

29], Jerri [

30], Shannon [

31]. In case of multivariate and randomly sampled data the recent work of Al-Ani and Tarczynski [

32] suggests two calculation schemes estimating the Fourier transform in the general case. The continuous time Fourier transform estimation (similar to Equation (

9)) takes samples with arbitrary spacing as the general approach, in contrast to the secondly proposed discrete time Fourier transform (

and

) estimation scheme. Here the data is projected onto a regular grid, which now may provide locations of missing data. Both schemes consider the sampling pattern

and its power spectrum distribution function

. However, even for such sophisticated methods, the main conceptual drawbacks (see points (i) and (ii)) remain, which motivates the subsequent Lomb-Scargle method as non OMD method and its extension to multivariate data.

2.3. Lomb Scargle Method

As described in the previous section, the disadvantage of OMD is that cosine and sine are not orthogonal on arbitrary intervals. By introducing an additional parameter

into Equation (

4) it will be shown that

holds for arbitrary intervals

. By utilizing the trigonometric identities,

and

, to remove the differences in the arguments the integral can be transformed to

If this integral has to be zero, the following condition has to hold

which can be transformed to

Therefore, from Equation (

12) the parameter

verifying Equation (

11) may be found. In case of equidistant sampling, the value of

can be directly calculated from the integration boundaries by:

Based on this general consideration and in order to remove the truncation error, for each frequency

the time shifting parameter

was introduced by Lomb and Scargle [

17,

18] into the model given in Equation (

1) so

The parameter

can be calculated by

similar to Equation (

12). For the time discrete version the integrals transform into a sum resulting in

The parameters

can be determined beginning with Equation (

7) but by factorising them by

, instead of expanding

to

as done for Equation (

8). In the following, the method is delineated for the discrete set

since it is applied to sampled data. This data is multiplied by

resulting in the next equation for a single frequency

:

where

. The sum of the terms

vanishes because of the proper selection of

according to Equation (

15). The sum of the terms

describes a modulated noise distribution function. The value of the parameters

can be directly obtained by dividing by

. This gives

The residual error term on the right hand side, , consists of a random distributed part divided by a sum over the square of the cosine. In contrast to OMD, the estimation error of the parameter only depends on noise and is independent from the realization of sampling.

The next step is to determine

in terms of a confidence interval with respect to

-quantile of the sampling error distribution

, as it was done for OMD in Equation (

10). Given a normal distributed error function with zero expectation value

and a standard deviation

independent from time (

), the error can be factorized (Parzen [

33], Theorem 4A, p. 90), leading to

estimating the most probable limits of

. In the above equation

neither depend on the frequency nor the shifting parameter and is defined as

The final parameter estimation gives

where the confidence interval

converges to zero by increasing the number of samples

N, for a fixed time interval. This property qualifies LSM to be a consistent estimator in amplitude and phase [

26]. In addition, the confidence interval

for the LSM is smaller than the value given in Equation (

10) for the OMD (this also occurs for the confidence interval of the parameters

,

). We notice that the definition of

given in Equation (

18) is slightly different from the original definition given by Lomb [

17] but both definitions converge for large

N (see supplementary material).

The confidence interval for the amplitude,

, can be deduced by propagating the error

:

In a similar way, the confidence interval for the phase

can be defined by

It is interesting to note that the confidence interval for the phase decreases for increasing amplitude.

3. Spectrum from the Lomb-Scargle Method

In order to determine the spectrum with LSM, we assume the recorded signal is described by many frequencies. The most significant frequency is then represented by a peak in the frequency spectrum of a certain width and height. The width is determined by the frequency resolution which equals . From this point of view the precision of a frequency estimation changes only with observation length T and seams to be independent from the number of samples N and signal quality.

The quality

is measured by a signal-to-noise ratio like expression

with

counting the

significant amplitudes. In Equation (

19)

is the fitted model,

is the uncertainty per sample, with

, and

is the noise per sample. Following VanderPlas [

34], we apply Bayesian statistics and assume that every peak is Gaussian shaped, i. e.

. It follows that a significant peak

appears at

, in a way that

is valid. Here,

is related to the power spectral density

. The frequency uncertainty (or standard deviation) is then given by

so that a significant peak is located in the interval

. This approach suggests that increasing the number of samples in a fixed interval

T enhances the precision of

by reducing

However, if the original signal contains two frequencies with a distance in the range of

, it cannot be excluded even for LSM that these peaks merge together in one single peak with small

according to Kovács [

35].

Concluding the properties of LSM: (i) there is no truncation error ; (ii) LSM provides a better noise rejection compared to OMD, ; (iii) the explicit sampling pattern is not of interest to work with LSM.

5. Application

The selected applications are ordered by increasing complexity of the sampling, and the data itself. First, a regular grid with missing values for a synthetic test data is considered. Second, Ultrasound Doppler Velocimetry (UDV) measurement data, which contains jitter and missing values is analized. Finally, a quite general data scenario given by an astrophysical 2D set of Sunspots, which appear freely in time and space, is investigated.

5.1. Synthetic Test Data

We start with a simple test case, where the input signal is a simple two dimensional plain wave

, with

and

representing the dimensionless frequencies, specifically selected in such a way that

, with

and

. The 2D sampling of

is performed with

. With respect to the chosen frequencies

and

it becomes evident, that both frequencies do not fit to the data range by an integer fraction. Data gaps are introduced by removing randomly distributed and uncorrelated grid points covering 60% of the total data set.

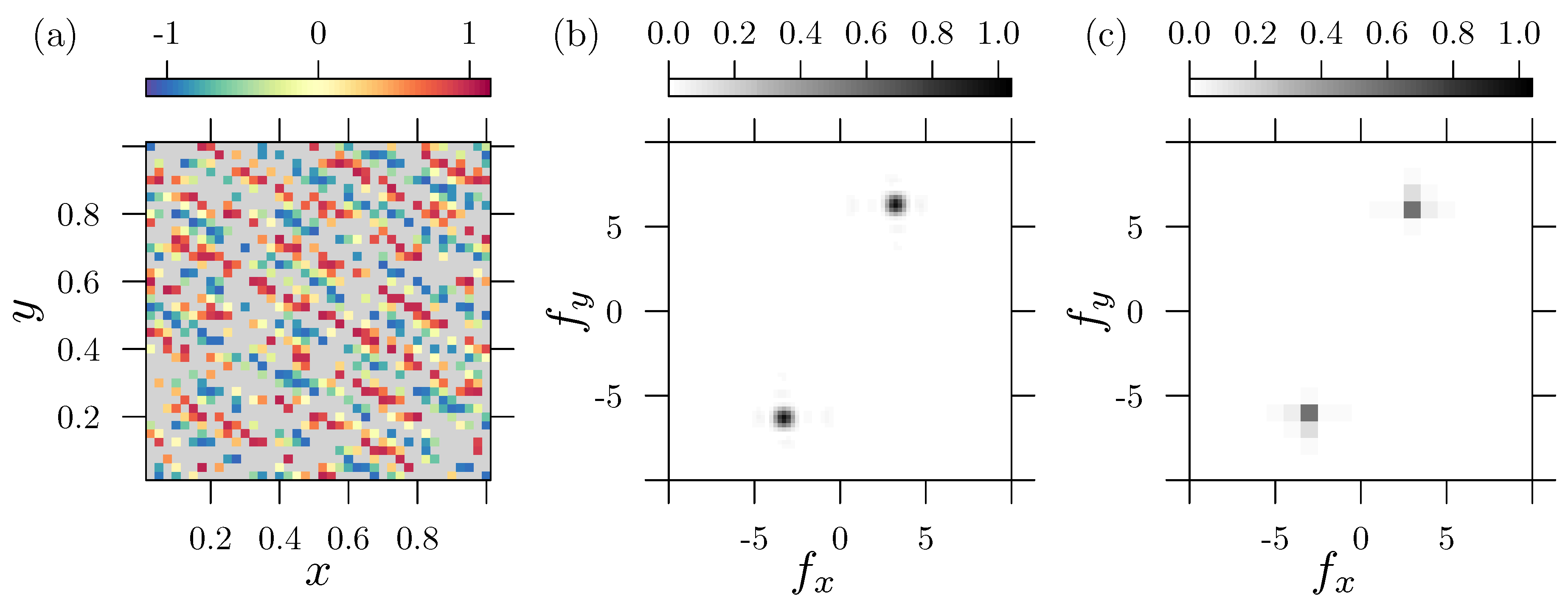

Figure 2(a) shows the nonuniform distributed input data. Gray areas indicate missing values (non available numbers “

”). As LSM requires an appropriate input vector of frequencies we choose for both variables

with a resolution of

.

The corresponding power spectral density (PSD) from the LSM (see supplementary material), shown in

Figure 2(b), displays the maxima at the 1st and 3rd quadrant, which represents a wave traveling upwards. The figure illustrates that even with a huge amount of missing data, it is possible to properly detect the periodic signal. In the present case, the value of

indicates a perfect fit to the corresponding sinusoidal model. For comparison,

Figure 2(c) depicts the standardized PSD

calculated from a discrete Fourier transform DFT symbolized by the operator

. Here, missing values (

) are handled by zero padding which means that the introduced gaps are filled with zero. Since the DFT represents a conservative transformation (mapping) into the spectral domain, zero padding leads to a significant reduction of the average signal energy. A proper rescaling to the number of zeros

(missing values) is required, to ensure approximated amplitude estimations. Zero padding always changes the character of the input signal, in a way that the corresponding DFT threats the zeros as if they where part of the original signal. The resulting PSD becomes then finally different from the original one. Since the signal frequencies

do not fit into an integer spaced scheme of the data range, the DFT suffers from its drawbacks, as is briefly discussed in

Section 2.2. The effect of leakage and misfit of frequencies can be recognized in

Figure 2(c), in terms of a rather coarse resolution and a lower PSD value.

5.2. 3D UDV Flow Measurement

The second example is taken from previous experimental flow measurements [

22] devoted to investigate the azimuthal magneto-rotational instability AMRI. The experiment consists of a cylindrical annulus containing a liquid metal between the inner and the outer wall. The inner wall rotates at a frequency

whereas the outer wall rotates at a frequency

. The flow is driven by the shear, since

. Two ultrasound sensors mounted at the outer cylinder, on opposite side of each other and at the same radius, measure the axial velocity component

along the line of sight parallel to the rotation axis of the cylinder. Additionally, the liquid metal flow is exposed to a magnetic field

(

r is the radial coordinate), originated from a current

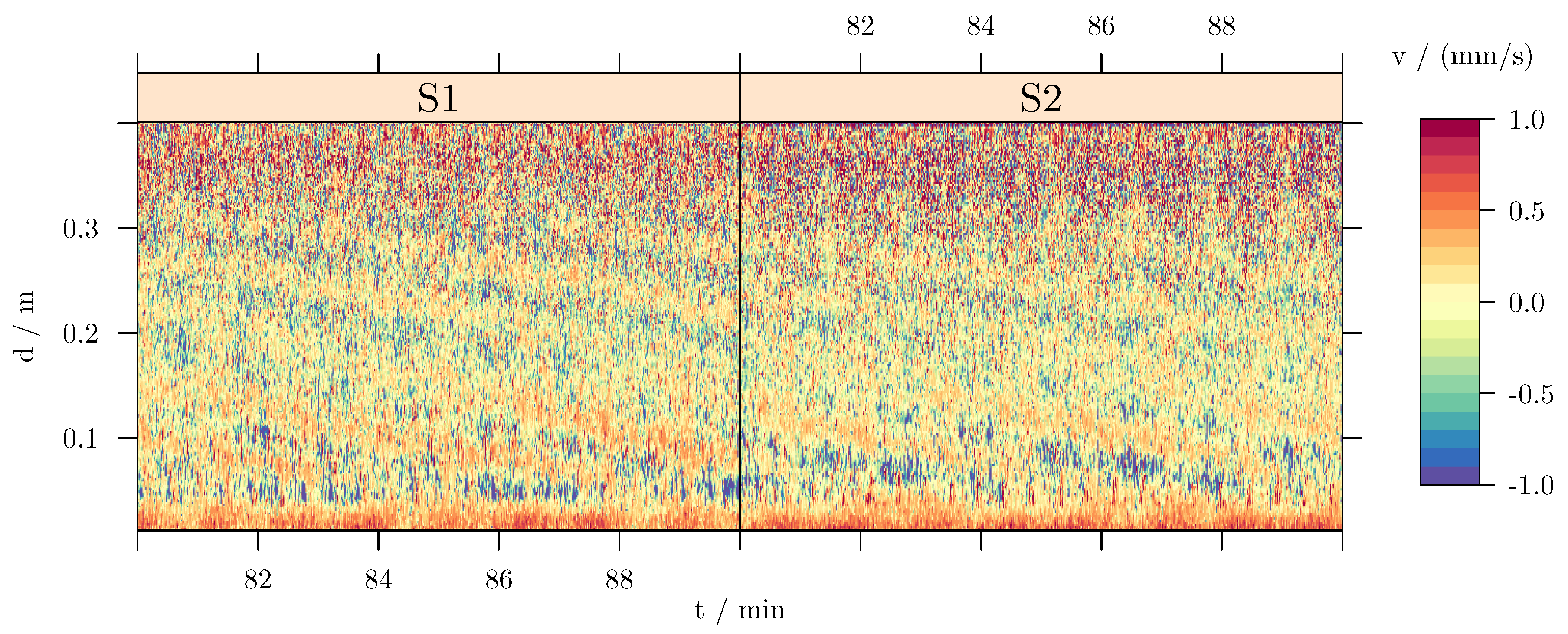

on the axis of the cylinder. A typical time series of the axial velocity (along the measuring line) is displayed in

Figure 3. The existence of periodic patterns (large blue inclined stripes) in this figure indicates a travelling wave propagating in the fluid. In cylindrical geometry, a travelling wave is described in terms of the drift frequency

, the vertical wave numbers

k, and the azimuthal wave numbers

m. A close look to

Figure 3 evidences that this wave is not axially symmetric, and that the leading azimuthal wave number is

. This is indeed proven in the following with the LSM analysis.

The measured time series for depends on time , depth and the angular positions of the sensors and , where the subscript n indicates the sampling. The azimuthal angles depend on time, since the sensors are attached to the outer wall. This induces the mapping , where is meant to be one out of the set of two sensors at each sampling instance. Finally the measured velocity component is a mapping , which fits perfectly to the proposed multivariate LSM.

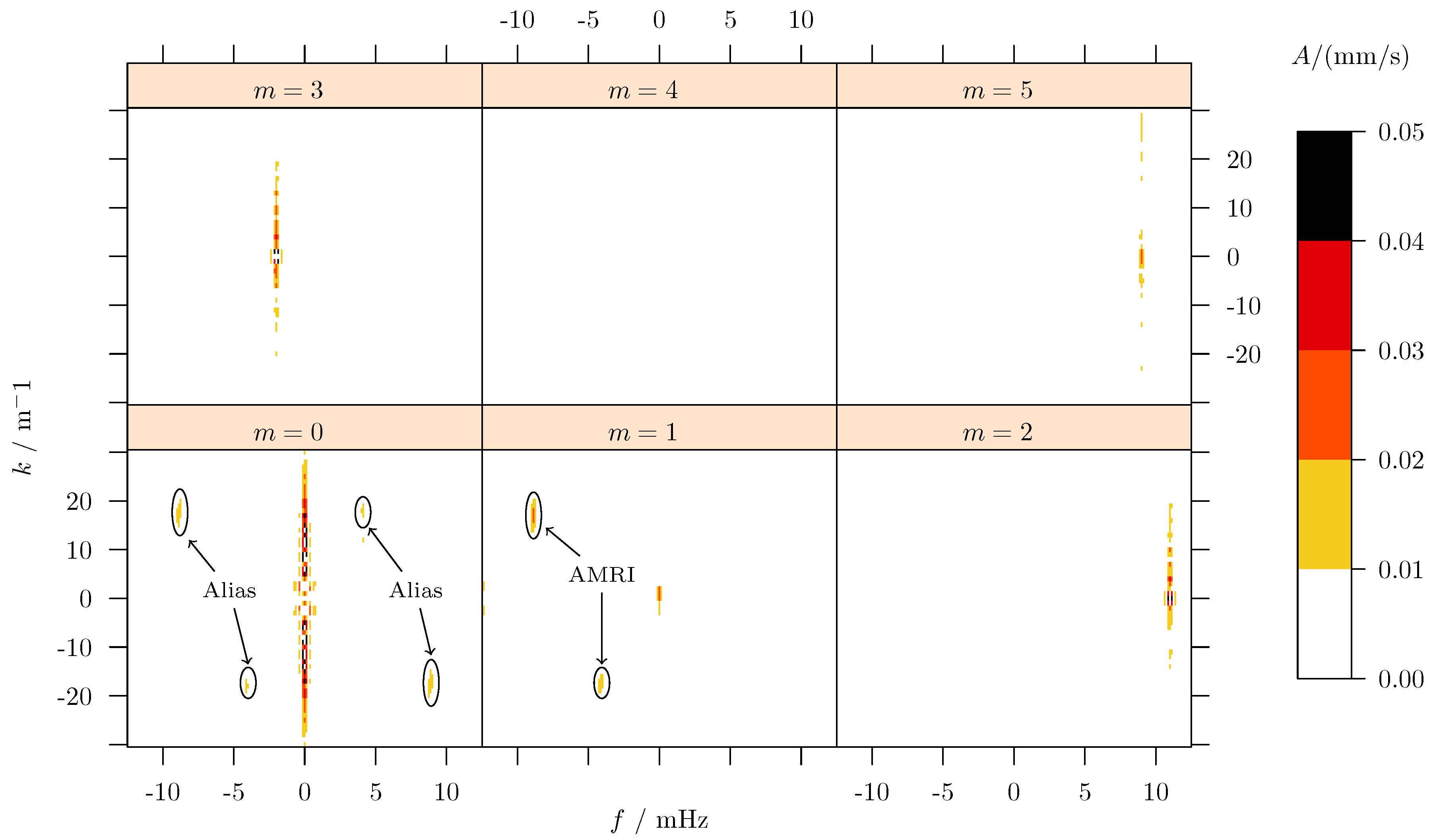

Figure 4 illustrates the result of the LSM decomposition into several azimuthal

m-modes with the corresponding amplitudes. The

mode contains a stationary structure, at a frequency

, which originates from sensor miss-alignments and (thermal) side effects in the flow. The minor non-stationary components, here the two point-symmetric peaks, originate from cross-talk (or alias projections, see labels on

Figure 4) of the

mode. This is mainly for two reasons: First, because the sensors behave not exactly identical (e. g. misalignment or different sensitivity) and therefore respond slightly different to the same flow signal. This means that one of the sensors projects a little bit more energy into the data than the other, which leads to a “leakage”-effect and a weak signal in

mode. Second, the rotation of the sensors acts like an additional sampling frequency

. In consequence, the spectrum of this regular sampling function folds with the spectrum of the observed process, leading to alias images (copies) of the original process spectrum into other frequency ranges (i. e.

m’s). In the present multivariate analysis, these alias structures exhibit point symmetry in

panel, indicating corresponding traveling waves. It is evident that these aliases originate as a systematic error from the LSM method and, due to their symmetry, effectively cancel each other out. One could also argue, that multivariate LSM enables a robust identification of alias amplitudes, which do not belong to the observed process.

The AMRI wave itself is located in the panel, with a characteristic frequency in time (f) and in the vertical direction (k). Here, two components can be identified: the dominant wave at and and a minor counterpart at and . The signals observed in the and panels might be due to aliases, because of the rotation of the inner cylinder at a frequency .

The advantage of “high” dimensional spectral decomposition is the improved noise rejection. With respect to the raw data, given in

Figure 3, it is obvious that high frequency noise is present in the data. Depending on the exact distribution of this noise, its energies spread over a certain range of frequencies. If we would select a representative depth and angle so that

, the velocity

only depends on time. In the subsequent one dimensional analysis the noise would accumulate along the single frequency ordinate probably hiding the signal of interest. Taking the higher order analysis distributes the noise energies over multiple domain variables. For the present example, this means that the distortions are projected into higher frequencies

f, higher

m’s and larger

k’s. Since the signal of interest remains in the same spectral corridor, its signal amplitude becomes more clear, because of the “reduced” local noise.

5.3. Analyzing 2D s Unspot Data

Since the beginning of the 17th century systematic visual observations of Sunspots are available. This allows to investigate dynamic processes taking place in the Sun. The appearance of Sunspots on the Sun’s surface depends on the level of solar activity, and therefore it renders some fundamental features of the underlying solar dynamo, such as the

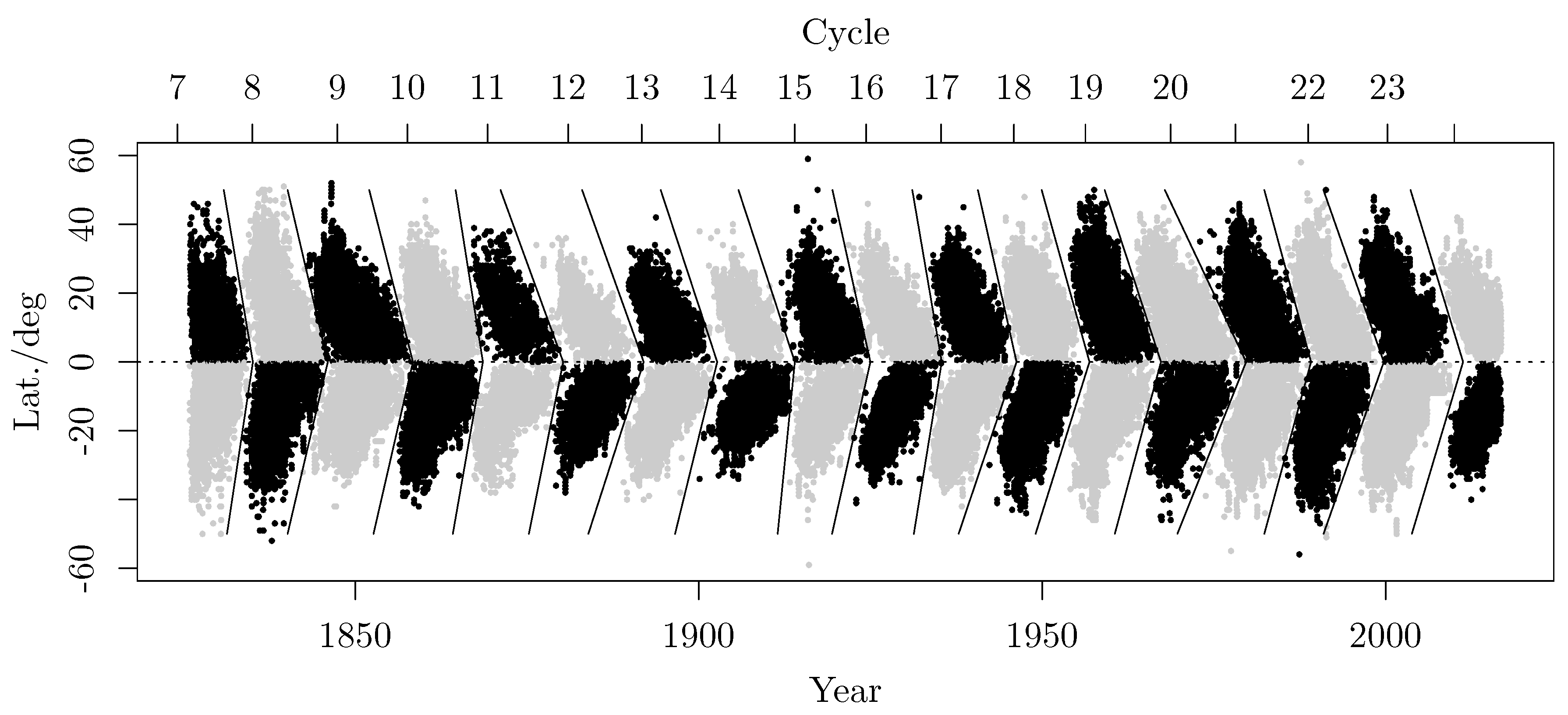

solar cycle. Since the beginning of the 1820’s observational data is available, in terms of a two dimensional time series displayed in

Figure 5. The data exhibits a periodic wing-like pattern essentially symmetric with respect to the Sun’s equator, the Sunspot butterfly diagram. This diagram summarizes the individual Sunspot groups appearing, at a certain time and latitude on the Sun, for the past 190 years. Additionally,

Figure 5 depicts the assigned field polarity order indicated by the Sunspot color (gray or black). Given a year

Y and a mean latitude

L (degrees), the field polarity

gives the arrangement of leading North/South polarity of a Sunspot group. This polarity is changing approximately each 11 yrs, which is called Schwabe’s cycle. The full period of

is called the Hale cycle. The segmentation of

Figure 5 is obtained following suggestions from Leussu et al. [

36], but with some simplifications leading only to minor miss-assignments for individual Sunspot groups.

The Sunspot data is taken as-is from Leussu et al. [

37], which originates from several sources with different qualities, i. e. the Royal Greenwich Observatory – USAF/NOAA(SOON)

1[

38,

39], Schwabe

2[

40] and Spoerer

3[

43] data sets. A detailed discussion of the data collection is given by Leussu et al. [

36], Leussu et al. [

37] and the referenced literature.

In this section, the LSM spectral decomposition from this unevenly sampled binary data set is obtained, in order to identify typical periods. In contrast to the two examples analysed in

Section 5.1 and

Section 5.2, the Sunspot data set consists of real arbitrary sampling in both, time and space, providing the most general scenario input data for the LSM. The starting point for the subsequent analysis is the simplified segmentation of the butterfly diagram reassigning the field polarity. The segmentation takes place by optimizing the distance

d (in the

-plane) between each Sunspot and the segmentation line

which is a piece wise linear function with intersection point

. The individual slopes, with

, are assigned on the northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. The final segmentation of

Figure 5 consist of 18 individual cycles subdivided by a > - shaped separation area.

The LSM spectral decomposition is based on the definition of a two dimensional wave model

where

P is given by the assigned patch polarity. To show the advantage and robustness of the LSM the raw data is employed without any further preprocessing. The selected frequencies

are given on a rectangular grid with inverse distance so that the periods are distributed uniformly alongside the consecutive counter

n. Furthermore, the frequency resolution close to

is selected finer to better resolve this region.

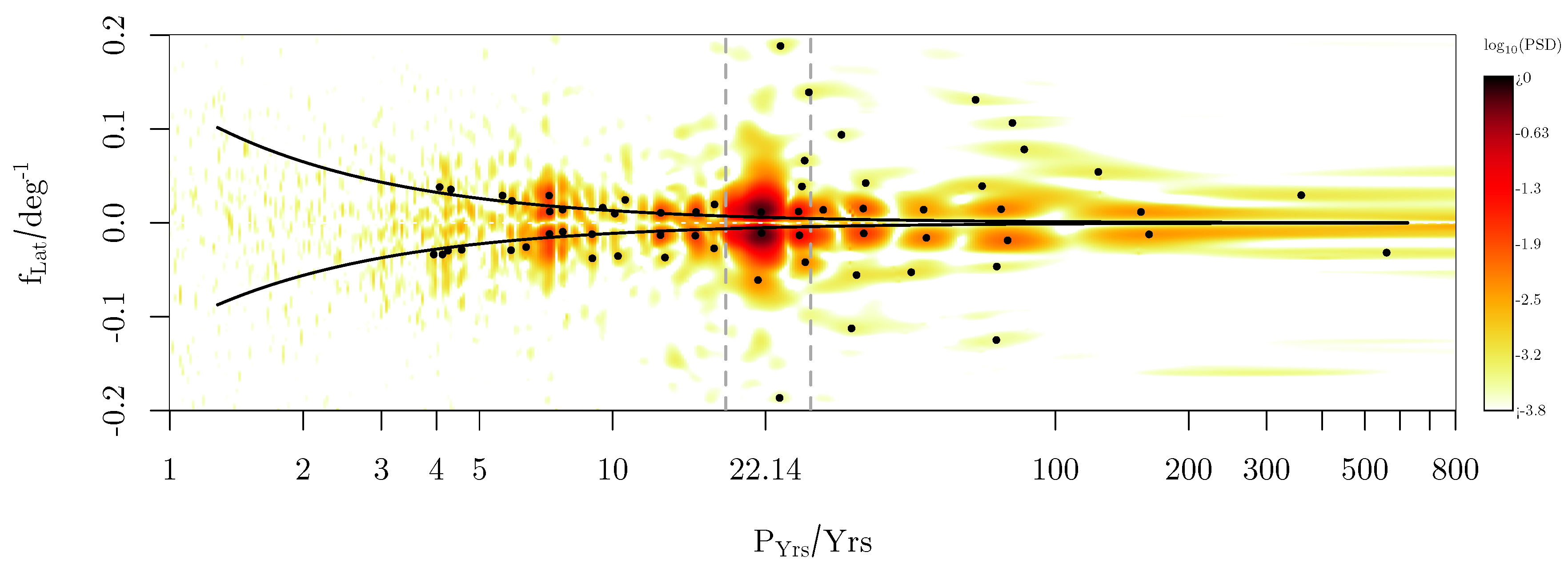

Figure 6 gives the resulting LSM spectral decomposition in a reciprocal log-scale plot to analyse the different periods. Each of the selected peaks (numbered black dots) provides a FAP value of

, meaning that these periods are significantly different from noise level. Each of these points originate from a local frequency refinement to achieve the local maximum amplitude. The binary order information

induced by the Sunspots, introduces higher harmonics into the spectrum, which do also appear with a significantly low FAP value.

Figure 6 provides good agreement between the peaks found and the common known periods.

Table 1 summarizes the major outcome in comparison with literature. For example the

Hale cycle varies from

(Usoskin [

44]) which is identified by the two main peaks. Since the solar cycle is modulated, refer to Hathaway [

45], it is natural that a broad spectrum with many harmonics becomes present. These subsequent patterns are related to a set of local maxima mainly collapsing on a horizontal line at

, indicating that the complex structure of the individual wing-shapes of the butterfly diagram with different widths, heights and orientation, corresponds to a main period

. Next to that we can identify typical periods which are related to the Gleissberg process (see

Table 1) or the short periods in the range of

, which are consistent with the data provided by Prestes et al. [

46], Kane [

47] and partly with Deng et al. [

48].

The latitudinal dimension of the spectrum spreads the peaks vertically which is a great advantage compared to a purely 1D analysis, where all signal would be projected on the

line. In addition, complex patterns such as lines of constant phase velocities (dashed curve of

Figure 6) may be used to analyse modulations of the dynamics of the Sunspot motion.

6. Conclusions

In the present work a multidimensional extension of the Lomb-Scargle method is developed. The key aspect is the redefinition of phase argument to . We suggest using a modified shifting parameter in contrast to the traditional approach which shifts the ordinate instead of the phase. This enables multivariate modeling with one single scalar value for all independent variables as there is always a shifting parameter for which vanishes on any interval .

With respect to the evaluation of measurement results, the noise rejection and confidence intervals ( and ) of model parameters and are delineated. To emphasize the advantages of the LSM the traditional Fourier mode decomposition is compared. It turned out that the systematic error does not vanish for FT based methods with increasing number of samples on a fixed interval T, which finally lead to the common leakage effect. Here the signal amplitudes are distributed on an area of neighboring spectral components, i. e. individual bins or pixels. We conclude that the standard orthogonal mode related procedures do not represent a consistent estimator for model parameters and . Whereas the introduction of in LSM leads to a consistent estimator with even for higher dimensions. Finally, it was shown that LSM converges to the true model parameters with increasing number of samples and provides a better noise rejection () as well.

The examples from

Section 5 underline the strengths of the developed procedure in a consecutive way. First the application on ideal two dimensional test data shows the ability to analyze fragmented time series. Here the sampling remains regular meaning

with

, but with

as an incomplete set of locations to describe missing values. A second quasi similar situation is given in the experimental data set of UDV measurements, expect a certain jitter. The dimensionality in this example was extended to

to decompose the wave parameters in frequency

f, symmetry

m and spatial frequency

k.

As the third analysis, the Sunspot data sets represent the most general case of non-evenly sampling. Taking only the time series of positions into account, LSM is able calculate the spectrum on a individual frequency grid pronouncing the low frequencies close to zero. The assignment of to each data point is a minor modification so the data can be assumed as binary raw data. The spectral decomposition with LSM shows the characteristic footprint of waves and its dynamics present in the butterfly diagram. The time frequency spectrum itself provides the commonly known frequencies, i. e. Hale-Cycle or Gleissberg process. The second frequency provides information about the minor peaks which are spread out into the latitudinal domain. Moreover, from these values the Sunspot drift motion may be calculated using a characteristic v-line with its side bands.