1. Introduction

The digitalisation of building permits has been widely investigated in recent years (Noardo et al., 2022; Beach et al., 2024; Noardo, Fauth, 2024). A common highlight among such experiences, in research and in practice, is the difficulty of building authorities to understand and manage the overall issue, considering the variety of aspects involved, and to orient themselves across the solutions to formulate a suitable plan for the digital transition in practice, adapted to their needs.

Maturity Models are key tools for evaluating digital transformation across a wide range of sectors including government, business, and infrastructure. In the context of digital building permits, these models can offer structured frameworks to help authorities understand where they stand in their digital journey and identify how to move forward. As Wendler (2012) notes, maturity models have evolved significantly, and their structured approach is valuable for identifying improvement areas and setting milestones for development. For building permit systems, they could span a wide spectrum, from basic digitisation efforts to the integration of advanced technologies like Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

To navigate the complexities of digital transformation in building permits, municipalities benefit from structured frameworks that not only assess current capabilities but also provide clear pathways for advancement. Maturity models serve this purpose by offering a systematic approach to evaluate processes, technologies, and organizational structures. They enable stakeholders to identify specific areas for improvement, prioritize initiatives, and monitor progress, as well as drawing a roadmap to guide, plan and report developments. In the context of digital building permits, maturity models can guide authorities through the stages of digitalization, from initial adoption to full integration of advanced technologies like BIM and GIS.

Some examples of digital building permit maturity models were developed in the past (Braholli et al, 2023) (

Section 1.1), but they are often covering only one or few aspects or domains which are interrelated with others in the building permit digitalisation topics (e.g. building information modelling and design, regulations management, geoinformation management, checking tools, business and organisational aspects). In other cases, the maturity models are intended to represent the overall issue, but they are kept to a very high level. It is good to have a very synthetic indication of the maturity achieved, but it is hardly applicable in practice as a tool to assess the progress towards digitalisation at a granular level, and to support further integrations.

Building on existing examples, this paper aims to develop a digital building permit maturity model that has strong support from stakeholders and can be used as a practical tool to guide digitalisation, starting with a clear assessment of where organisations currently stand.

The resulting maturity model is a valid reference for building authorities to assess the digital maturity of their building permit process and guide them through feasible implementations. More accurate and granular insights into the building permit digital maturity across countries and different cases will also become possible, as a guide for investments and developments.

In this paper,

Section 1.1 reports the state of the art about maturity models for digital building permitting, which is also an essential base for the methodology followed.

Section 1.2 reports more details about the maturity model for digital building permits which was developed within the CHEK project (2022), the most mature example, selected as a reference to be further improved and validated within this study.

Section 2 describes the methodology followed and

Section 3 reports the results of the validation activities as well as the final maturity model, integrating the improvements and feedback.

1.1. State of the Art on Digital Building Permit Maturity Models

Studies (e.g., Shahi et al., 2018) point to widespread inefficiencies in traditional and partially digital processes. The case of Toronto reveals that manual workflows, inconsistent interpretations of codes, and isolated communication severely delay project approvals. Similarly, international comparison with the Israeli system accentuates the value of standardised digital procedures in improving permitting speed, clarity, and fairness (Fauth et al., 2023). Such inefficiencies lead to increased cost and reduced public trust, further highlighting the need for structured digital transformation.

Significant advancements in the digitalization of Building Permit Processes have been achieved through initiatives like Finland's RAVA3Pro project (2023) and Estonia's e-construction portal (Pàrn et al. 2022; Lavikka & Kallinen, 2024; Jakobson, 2019).. Nonetheless, despite the clear advantages of digital transformation, building authorities still face numerous barriers. Interoperability problems, legacy IT systems, limited digital skills, and regulatory ambiguity contribute to the slow pace of change (Noardo et al., 2022; Mêda et al., 2024). Financial constraints and resistance to change within organisational culture also pose significant hurdles, particularly in smaller municipalities. Tied with public policies, technical standards need to be effectively harmonised with local procedures and legal frameworks (Urban et al., 2024). Moreover, beyond technology, digitalisation demands a cultural shift, occasionally requiring new ways of thinking, new skills, and new roles. For many municipalities, particularly smaller ones, the resources to support this transition are scarce, making the path forward even more challenging.

The literature underscores the importance of Maturity Models in facilitating this digital transformation (Ochoa-Urrego and Peña-Reyes, 2021). Kafel et al. (2021) developed a multidimensional digital maturity model for public sector organizations, emphasizing dimensions such as digitalization-focused management, digital competencies of employees, and openness to stakeholders' needs. These models not only provide a benchmark for current practices but also help in aligning technological advancements with organizational goals and regulatory requirements.

Furthermore, to be effective, maturity models must be grounded in integrated conceptual frameworks that reflect the realities of the domain they are meant to assess. For example, Hjelseth (2013), in the “L+I+C model” emphasises the interconnectedness of legal, informatics, and construction aspects. This approach recognises the complexity of digital permitting, where technological systems need to work in relation with organisational procedures and regulatory structures. Building on this, Shahi et al. (2019) proposed an automated, BIM-based e-permitting system that demonstrates how digital tools can improve permit workflows, reduce errors, and enable better compliance through structured information management. Such approaches highlight the importance of aligning digital tools with both procedural and legal framework to avoid conflicts and inefficiencies.

Despite the widespread use of maturity models in related domains, such as the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) in Information Technology, the Cyber Assessment Framework in public administration, and the GovTech Maturity Index in digital governance, there remains a striking lack of a model specifically designed for the digital building permitting context (CMMI Institute, n.d., National Cyber Security Centre, 2022; World Bank, 2022). The existing models are often too generic or too focused on individual aspects, such as IT infrastructure or management processes. They typically don’t account for the specific interplay of legal, organisational, technological, and data-centric challenges that permitting authorities face. As a result, they fail to offer meaningful guidance or benchmarks for practitioners operating in this highly specialised field. This gap indicates a critical need for domain-specific tools that consider both operational realities and strategic objectives.

The Technology–Organization–Environment framework (Baker, 2011), which has been applied in the ACCORD project (2022), is a helpful step toward understanding broader drivers of adoption. It offers a balanced view of the technical, organisational, and contextual factors at play. However, it remains too high-level for accessible implementation planning. Similarly, the Common Assessment Framework (European Institute of Public Administration, 2020) provides useful quality management guidance for the public sector, but it does not address the unique technical and regulatory requirements that digital building permit entails.

Recognising these gaps, Fauth et al. (2024) developed a taxonomy for organising knowledge within the building permit domain. This taxonomy offers a clear structure for categorising the various components and stakeholders involved, which is crucial for comparing systems across jurisdictions and for communicating clearly among professionals. When used in conjunction with a maturity model, it adds conceptual clarity and consistency. However, while taxonomies structure understanding, they do not guide action and a robust maturity model is still required to turn this knowledge into a practical transformation roadmap. In particular, integrating taxonomies with maturity models allows authorities to prioritize interventions and allocate resources more effectively.

That was the aim of the CHEK Maturity Model (Ataide et al. 2023a), developed within the CHEK project (Section 1.3) and evolving in this study through the collaboration within the European Network for Digital Building Permit (EUnet4DBP, 2020). It was the first model built on purpose for digital building permits. The maturity model developed in the CHEK project, following the digital building permit taxonomy, breaks the digital transformation journey into four main dimensions: process, organisation, technology, and information. Each dimension is further divided into key capability sets and maturity levels, allowing for a granular, incremental approach to transformation (Ataide et al., 2023b). The model is grounded in real-world practice and includes built-in mechanisms for feedback and adaptation, making it not just descriptive but actionable.

Providing such a comprehensive model requires balancing theory and practice. It must incorporate technical standards, like the buildingSMART Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) and the OGC CityGML, while remaining compatible with the varied legal, technical, and organisational landscapes of municipalities across Europe (Urban et al., 2024; Aguiar et al., 2019).

1.2. The CHEK maturity model

The maturity model developed in CHEK (Ataide et al., 2023) is a structured framework designed within the CHEK project to serve as both an assessment and a planning tool. The model aims to evaluate the digital maturity of existing processes, identify areas for improvement, and leads to a roadmap, suggesting a strategic path for evolving from traditional workflows to fully digital and integrated systems, especially leveraging the CHEK results and tools. This ensures municipalities can prioritize actions based on their current needs, available resources, and long-term goals.

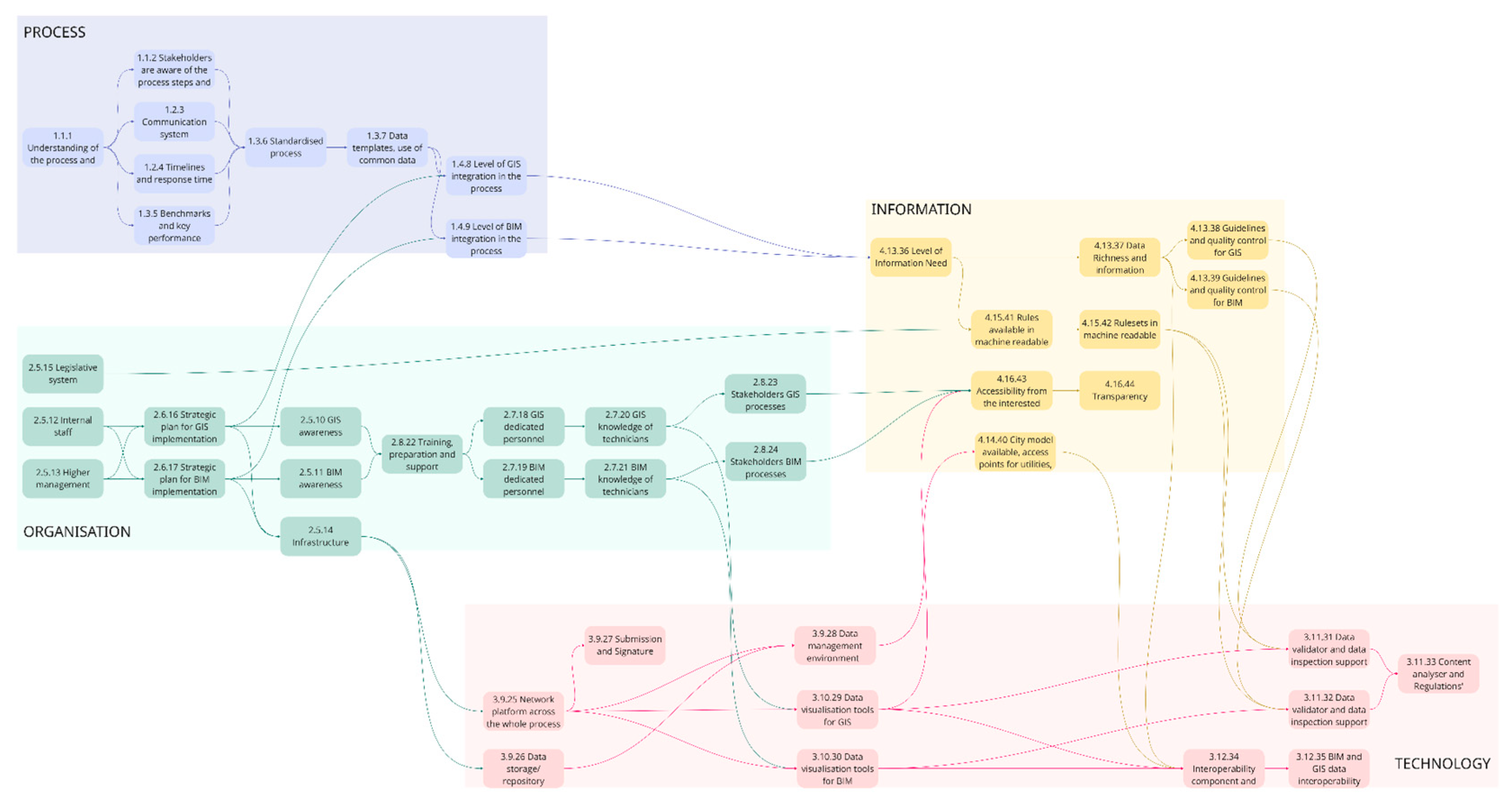

The CHEK maturity model is divided into four main ‘Categories’: process, organization, technology and information, divided, in turn, into ‘Capability sets’, each of which contains several ‘Key Maturity Areas’ (KMAs). The ‘Process’ category assesses workflows, integration, and standardization within the building per process, evaluating the completeness of task mapping, automation, and transparency. The ‘Organization’ category assesses the municipality's maturity for digital transformation, including leadership commitment, staff alignment, and organizational culture, and considers the presence of dedicated personnel, training programs, and strategic vision. ‘Technology’ evaluates the supporting software infrastructure, such as document management systems, submission and communication platforms, as well as interoperability of digital tools. Lastly, ‘Information’ category focuses on data quality, data governance, and data management, assessing standards, accessibility, and regulatory compliance (

Figure 1).

The KMAs are the lower level of the maturity model, in which the assessment occurs. Each KMA is scored on a six-level maturity scale from Level 0 (Non-Existent) to Level 5 (Optimized), which indicates the progression from basic to advanced digital maturity (

Figure 2). The model incorporates dependencies between different Key Maturity Areas, ensuring that foundational elements are developed before moving to more advanced capabilities in a logical and achievable progression.

Once the assessment is ready, the model can lead to a roadmap based on the state of the art maturity and the desired maturity levels. To ensure the CHEK maturity model practical applicability, an initial validation was performed during structured workshops within the four CHEK pilot municipalities (Ascoli Piceno - Italy, Prague - Czech Republic, Lisbon and Vila Nova de Gaia - Portugal), as well as asking for feedback to the advisory board and community of practice, involving additional building authorities and actors.

This phase of testing (CHEK Project, 2024) was done by expert-led semi-structured interviews to municipality employees skilled in building permit processes and digitalization strategies. A set of questions were created to assess the current maturity of their permitting processes, using the CHEK maturity model as a reference framework. As well as to evaluate the applicability of the CHEK maturity model, gather feedback, and identify areas needing refinement.

The online interviews, lasting two hours, followed a structured format to ensure consistency and comparability of results. A detailed questionnaire of 35 questions was used to guide the assessment. The answers gave material to fill the CHEK maturity model areas and evaluate the state of the art of building permit digital maturity of the municipalities. The questions were grouped into six themes to ensure clarity and minimize overlaps: Process and standards (how building permit processes are structured, mapped, standardized); Data management and standards (governance, quality control, data formats); Stakeholders’ integration and interaction (extent to which stakeholders are connected, communication methods, level of collaboration across parties); Organization and internal infrastructure (organizational readiness, digital infrastructure, strategic alignment of resources and goals); Checking (checking procedures, digital tools); Legislation (compliance with regulatory requirements, accessibility of legal documentation). Follow-up questions were included where appropriate to clarify responses or explore relevant details.

After the interviews, experts filled the maturity models based on the answers received. To decrease subjectivity, a level was considered as fulfilled only if all its content was true. For example, if a municipality had partially mapped processes but lacked documentation, it was categorized at a lower maturity level than the one implying both process mapping and documentation in place.

In a subsequent testing phase (CHEK Project, 2025b), municipalities used the CHEK Virtual Assistant (CHEK Project, 2025a), a digital tool that incorporates the CHEK maturity model. The assistant allows municipalities to assess their building permit maturity automatically, using process information they have mapped themselves.

The challenges identified during testing and interview feedback helped improve and expand the initial version of the CHEK maturity model. First, the high-level descriptions of KMAs were often too broad, leading to ambiguities in assigning maturity levels for non-experts. Second, although the initial model was already detailed, it was still not granular enough to capture the levels of maturity accurately, which affected objectivity. Maturity levels were therefore split into sublevels to improve precision and usability. This was also useful to address another issue, namely, the representation of characteristics that fell between levels, making it difficult to assign them to a single one. For example, some processes were partially digitalized but lacked integration into a digital environment, but there was only one level that addressed both aspects.

Sublevels divide each level into smaller, measurable components, enabling more precise assessments and recognizing progress. This granulation also helps to provide a clearer and more objective roadmap for municipalities to advance to higher levels of maturity (

Figure 3). Progress within a level is now assessed proportionally. For example, if a level has three sublevels and a municipality achieves one, it is considered to have reached 33% of that level's maturity. Dependencies between sublevels are limited to cases where foundational capabilities are required before advancing (e.g., documenting process steps before integrating them into a digital system).

Figure 3.

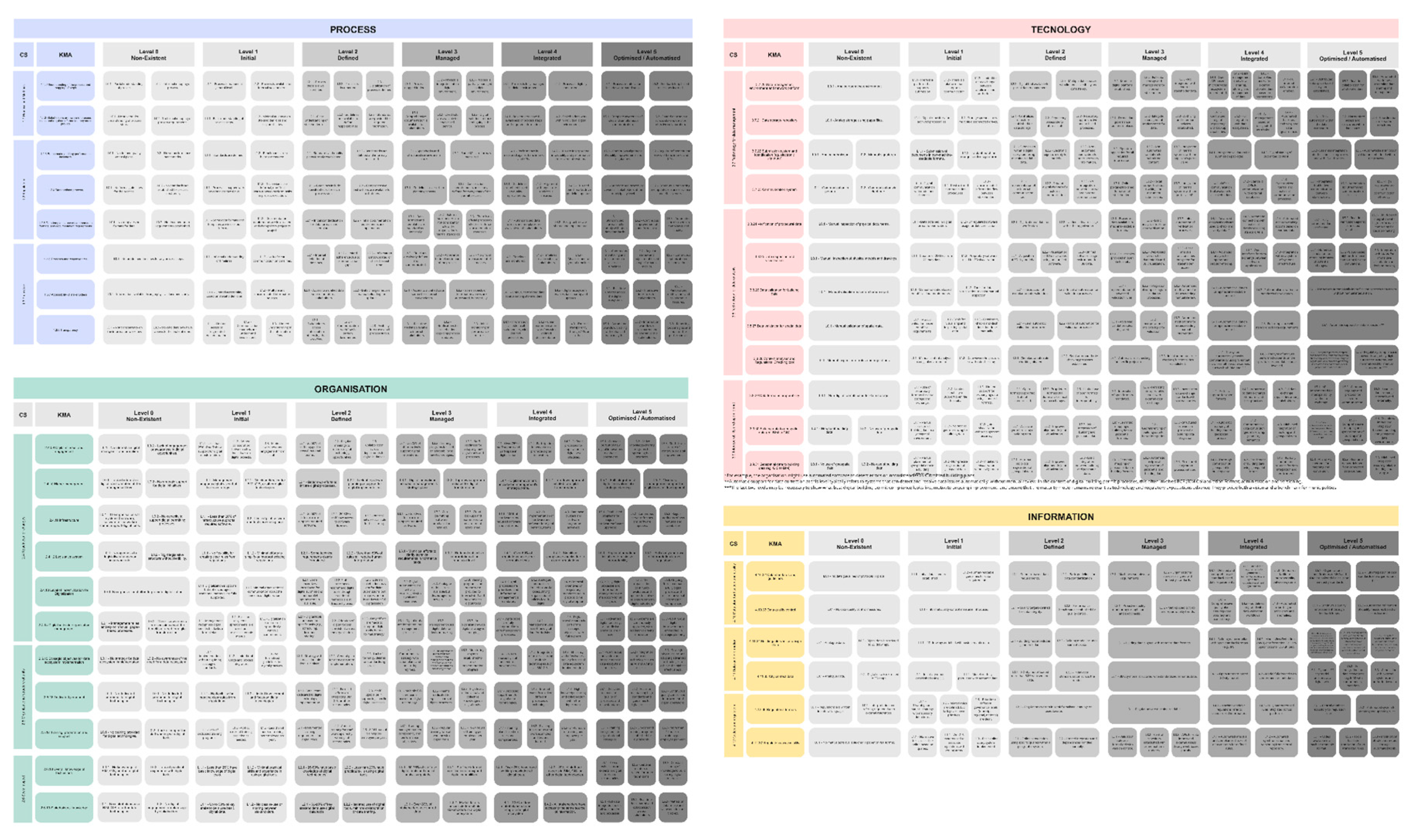

Example of sub-levels in the CHEK maturity model under the Process category The resulting Digital Building Permit Maturity Model retains its original structure according to the four categories (process, organization, technology, and information) but incorporates sublevels to reflect progress (

Figure 4)(Braholli and Ataide, 2025).

Figure 3.

Example of sub-levels in the CHEK maturity model under the Process category The resulting Digital Building Permit Maturity Model retains its original structure according to the four categories (process, organization, technology, and information) but incorporates sublevels to reflect progress (

Figure 4)(Braholli and Ataide, 2025).

Figure 4.

Overview of the maturity model developed within the CHEK project .

Figure 4.

Overview of the maturity model developed within the CHEK project .

2. Methodology

A key aspect of this study’s methodology is the collaboration among authors from diverse backgrounds and areas of expertise, which strengthens the testing and validation of the maturity model and supports its acceptance at the European and international levels. Such a working group was constituted within the EUnet4DBP. The EUnet4DBP was established in 2020 with the goal of fostering multi-stakeholders collaborations around the topic of digital building permits and finding a larger consensus.

An essential first step of the methodology (

Figure 5) was considering existing examples, on the topic of digital building permitting and related domains (e.g., design data management, geospatial data management, processed digitalisation) (

Section 1.1). An analysis and comparison of the existing examples was performed and discussed among EUnet4DBP experts (i.e., the authors). An agreed version of the digital building permit maturity model, standing on up-to-date literature and examples from recent studies and projects resulted from this phase. Such intermediate results, built in particular on the maturity model for digital building permit developed in the CHEK project (

Section 1.2), are not reported here. This one was further validated (with respect to clarity, comprehensiveness, representativeness and user-friendliness) against a huge corpus of interview data about the building permit process in Europe (

Section 2.1) and by testing its autonomous (although assisted) use by stakeholders in the City of Vienna (Austria) (

Section 2.2) as an example case. The results of the evolution of the maturity models are presented in

Section 3.

A final step was the integration of all the feedback collected to provide a final validated version of the Digital Building Permit Maturity Model.

2.1. Test of the Agreed Maturity Model Against Interviews on Building Permit Process Data

To test the effectiveness of the maturity model, it was important to apply it to a wider range of building authorities and building permit processes beyond those CHEK. This helped assess how well the model reflected real practices and whether its maturity levels were clear and easy to use in practice.

To address this, we leveraged the data collected by part of the authors within a deep investigation of the current building permit processes over Europe, by means of a high number of interviews across several countries (Fauth et al., 2025; Fauth et al., 2024). These are used in this paper to validate the maturity model with respect to adherence to the current processes’ description needs across diverse cultures, legal systems and institutional specificities. This is a relevant step which was never made before, as maturity models for digital building permits are mostly developed as academic studies.

The collected interviews were selected to include different levels of digitalisation and building permit processes, besides defining a balanced sample in terms of geographical distribution and diversity in the jurisdiction size of the authority responsible for the building permit process. Finland and Estonia were selected due to their pioneering role in the building permit process digitalisation. Montenegro was selected as it has only one authority responsible for building permitting in the whole country. Sweden has some unique particularities related to processes, meaning that technical review is performed by the technical inspector that also performs on-site inspections. The UK differs in having the planning permitting and building control approvals (technical) separated and conducted by different departments. The aim was to analyse the interviews of different sized authorities. We categorised our interviews by the size of the authority jurisdictions, the small ones having less than 50.000 inhabitants, medium between 50.000 and 500.000 and large ones either bigger than 500.000 or capital city authority. From Finland, we used a small authority, for Sweden medium sized and for Estonia a large one. Montenegro has only national authority and for the UK we used an interview with the building control department, which is categorised as large.

The transcripts of the selected interviews (collected in the independent study by Fauth et al., 2025) were manually cross examined against the maturity model matrix. The fact that the interviews were conducted without the reference or guidance by the maturity model makes the validation independent of the model, and is therefore not biased. However, a lot of information in the interviews is not related to the maturity of building permit systems.

The first aim of the validation was to match the maturity model categories with the information in the interviews answers. Such matches were considered as a validity proof for the identified model categories. However, as the interviews were not guided by the maturity model, the direct matches were few. The matches were marked in the transcripts, associating the corresponding maturity model category information. Finding the direct matches was not the only and also not the most important aim.

In addition to finding the direct matches, more complex insights from the interviews were considered and classified in three kinds of feedback. The first of them was finding out what changes need to be applied in the maturity model. What can be found out from the interviews, for example, are the changes related to the ambiguities in the categories definitions. Second, some categories had to be added, corresponding to the information in the interviews that relates to the maturity of building permit systems but did not have a corresponding category in the maturity model. A final case regards the need to consider additional, less defined, aspects or topics, deserving dedicated discussion or which should be considered in future studies.

2.2. Test of the Agreed Maturity Model by Building Authority (City of Vienna)

In parallel, further testing of the achieved maturity model by interviewing building permit authorities, inviting them to use the model directly, allowed testing further its contents as well as its usability in terms of user-friendliness. This step was performed with authorities within the city of Vienna.

To ensure that the assessment was as objective and neutral as possible, a city that was not part of the previous studies and projects and which had an advanced digitalization strategy was selected, so that as many stages of the model as possible could be tested in practice. The city of Vienna was chosen due to its already extensive experience in the digital transformation of administrative processes through the European BRISE-Vienna project (2022). This combination of independence and digitalization expertise provided ideal conditions for validation. The survey took the form of a guided/table-assisted expert interview with the head of the City of Vienna's Department for Technology, Digitalisation and Innovation. The interview was conducted by the Vienna University of Technology, which was not directly involved in the CHEK project. This allowed a largely unbiased perspective on the maturity model to be evaluated. To ensure a thorough understanding of the model and related questionnaire intended to guide the filling, the interviewer received detailed instructions from the CHEK research team in advance.

To validate and develop the model itself, the following adjustments were made prior to the interview:

The maturity model was translated into German for the interview, with the original English text retained in parallel, to immediately clarify any potential conflicts or ambiguity due to the translation. The translation was carried out in a two-stage process: First, a machine translation was performed using DeepL, which was later manually revised in terms of language and content.

An additional column was added to the interview table to record the comprehensibility of the individual maturity level descriptions. The interviewee rated each statement on a scale from 1 (very easy to understand) to 5 (not understandable). There was also the option of adding explanatory comments to document any potential misunderstandings or ambiguities.

To enable a differentiated classification of implementation, another column was added to indicate whether a sublevel had been fully, partially, or not achieved (later, the option “pilot phase” was also offered). This differentiated feedback served not only for classification but also for identifying potential areas for development.

The interview took place on two dates – December 13, 2024 (duration: 2.5 hours) and February 6, 2025 (duration: 1 hour), with a total duration of 3.5 hours.

4. Discussion

The maturity model developed in CHEK served as the foundation for the maturity model developed in this study. Following comprehensive validation and testing across diverse municipal contexts with input from experts in various domains, the enhanced model retains the same four core categories: process, organization, technology, and information. However, significant structural and content modifications were implemented to optimize the model's effectiveness and clarity while preserving its fundamental concepts.

The digital building permit maturity model now encompasses 37 KMAs. Based on expert feedback, two additional ones were integrated into the Organization category: "Level of incentivization for digitalisation" and "Digitalisation in organisation management". This expansion addressed the identified gaps in these critical areas, which emerged as recurring themes among the municipalities studied in Fauth et al. (2024).

Regarding the model's structural framework, the updated version features more granular maturity levels. This refinement emerged from testing, which revealed that compartmentalized maturity assessments provide superior insights into real-world building permit scenarios. Consequently, the final version maintains the same six levels (0 to 5), but each level is subdivided into sub-levels that organizations can clearly relate to.

Concerning usability and accessibility, the validations demonstrated that the original text was sometimes complex and abstract, occasionally preventing users from accurately assessing maturity levels due to comprehension difficulties. The improved version incorporates more concrete examples and clearer terminology. The validation process resulted in meaningful model improvements. This rigorous development approach produced a robust, proven tool that effectively guides municipalities through their digital transformation journey. The obtained maturity model represents a ready-to-use resource that has incorporated expert input on digital building permits and demonstrates high potential as a comprehensive guide for organizations embarking on digital transformation initiatives.

Notably, feedback indicated a consistent pattern as the levels increased, so did the users’ difficulty in fully grasping what was required or achieved at that stage. This phenomenon has been observed in other digital transformation maturity frameworks. Lower levels typically describe familiar, observable conditions (e.g. manual work, informal procedures, or partial digitization) that are probably seen on a workday process while higher levels introduce more complex concepts such as system-wide automation, dynamic data flows, and organizational integration that are less commonly experienced and more theoretically demanding.

The abstraction and complexity at these upper levels partly reflect the cutting edge nature of digitalisation, where best practices are still emerging and often context specific. Users are less likely to have direct experience with real-time interoperability, comprehensive metadata management, or fully automated compliance systems. This unfamiliarity naturally leads to greater interpretive effort and occasional ambiguity. This also reinforces the need for a maturity model where those concepts could be a guide for the implementation of new improved processes.

The validation exercise highlighted ongoing challenges in categorising certain empirical realities, especially when an authority’s practices go across multiple levels for a single maturity area, or where digitalisation led to unforeseen process issues (e.g., an increase in incomplete or pending digital applications). The evolution of the digital building permit maturity model now incorporates process improvements such as pre-check phases to increase transparency and ensure higher-quality submissions.

The independent validation further emphasized that as a maturity model becomes more granular and comprehensive, it becomes both more useful and more demanding for users. This balance between completeness and usability remains a key consideration for future model development, with recommendations to continue evolving the model to encompass emerging areas, such as sustainability (eco and green maturity), and to provide supporting resources such as case studies and best practice guidelines.

One criticism was the considerable amount of time required to fully fill the model. Although additional aspects such as comprehensibility and commentary were surveyed as part of the validation, the total duration of 3.5 hours was considered high. A more compact version of the model could be desirable for practical use, especially in resource-constrained administrative units. However, as this model is intended as a practical instrument at an operational level, and not as a research tool, the time dedicated to filling the model directly translates into precision and comprehensiveness of the digitalisation strategy and roadmap, with the consequent prevention of unexpected events during the journey and cost optimisation.

Nevertheless, the analysis suggests a persistent need for ongoing dialogue and user support as digital maturity advances. Supplementing level descriptions with real-world case examples, visual aids, and practical checklists may further aid comprehension, particularly at higher maturity stages. The proposed maturity model will continue to evolve in line with this feedback, ensuring that it remains both rigorous and functional for authorities at all stages of their digital transformation journey.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented the validation of a maturity model specifically designed for digital building permit systems, aiming at providing a practical framework where generic approaches have proven inadequate. Our goal was to provide public authorities with a tool that enables realistic self-assessment and guides step-by-step their digital transformation.

The obtained digital building permit maturity model underwent a two-phase validation: first, through detailed analysis of interview data from a diverse sample of European municipalities, and second, in direct application within the City of Vienna. Each stage contributed valuable feedback, leading to key improvements such as clearer language, finer sublevel granularity, and new areas addressing organisational flexibility and digitalisation incentives. Both quantitative ratings and user feedback confirmed that the revised model is more accommodating and relevant for application in a municipal environment.

Through this validation process, the digital building permit maturity model has been both empirically tested and enhanced. The direct engagement with real-world data from a range of European municipalities and their respective building permit processes has produced a maturity assessment tool that is closer to the reality of current processes.

The results demonstrate that this maturity model fills a gap by offering a nuanced, evidence-based framework that accommodates the complexity and diversity of building permit digitalisation. It allows authorities to assess their current maturity, identify and support strategic planning customised to their unique context.

Looking ahead, further work will expand validation in additional municipalities, explore integration of sustainability criteria, and produce more advanced assessment tools and formats for everyday use. Continued feedback from practitioners will help keep the model useful and relevant as digital practices in building permitting evolve.

Future development will focus on establishing a continuous feedback mechanism to ensure the model remains current and relevant as digital building permit practices evolve. Additionally, plans include developing a simplified version of the maturity model or easier to access, designed to provide quick reference capabilities and enhanced accessibility for users who have less knowledge on the model and its content. Supporting tools may play a role in improving user experience, but the most effective approaches for providing guidance and operational planning remain open questions. In particular, future work should also consider the scalability of the model and its ability to address the full diversity of municipal realities across Europe. Ensuring that the maturity model remains both accessible and adaptable, regardless of authority size, digital maturity, or local context, will be a key challenge moving forward.