1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most lethal gynecological cancers, often diagnosed at advanced stages due to its asymptomatic nature in the early stages [Jayson, G. C., et al. 2014]. Despite advances in treatment, the five-year survival rate remains low, highlighting the urgent need for continued research into the molecular mechanisms and interactions that drive its progression [Lheureux, S., et al. 2019].

The interaction between different microorganisms in cancer patients, including the presence of bacteria, can enhance carcinogenic effects, creating a microenvironment more favorable to cell transformation [Francescone, R., Hou, V., & Garrett, W. S. 2014]. Exacerbating cancer progression by stimulating angiogenesis and metastasis, as in the case of colorectal cancer, where the bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum has be linked to more aggressive disease progression and poor response to chemotherapy [Kostic, A. D., et al. 2013, Li, R., et al. 2022]. With the bacteria even modulating the tumor microenvironment, causing suppression of the antitumor immune response [Duizer, C., et al. 2025].

Toxins such as CagA Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells cause the dysregulation of signaling pathways, altering cell proliferation, adhesion, and migration, and are therefore considered a key factor in gastric cancer [Rizzardi, P., et al. 2020]. Detect bacteria such as Mycoplasma hominis and Chlamydia trachomatis has in ovarian cancer, suggesting a possible role in chronic inflammation or co-carcinogenesis [Nishimura, M., et al. 2019, Bandera, E. V., et al. 2010]. Biomarkers of risk for ovarian cancer [Geller, R., et al. 2022], and various species of bacteria have been suggested that could be influencing tumor development, such as Escherichia coli [Smolarz, B. et al. 2024]. A bacterium that may also have the ability to modulate tumor progression in various tissues [Francescone, R., et al. 2014; Arthur, J. C., et al. 2012; Bhatt, A. P., 2017].

Gram-negative bacteria, including E. coli, are among the most prevalent in cancer patients [Taşkın Kafa, B. 2023; E. A. Al-Hajji et al. 2024; E. A. El-Seifi et al. 2019]. The toxin Colibactin produced by some strains of E. coli plays a role in breaking down the DNA of host cells, which has be linked to colorectal cancer [Arthur, J. C., et al. 2012; Lee-Six, H., et al. 2025]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the wall of Gram-negative bacteria, contributes to chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis [Liu, C.H., et al. 2021]. The outer membrane proteins of Gram-negative bacteria has be indirectly linked to contributing to a microenvironment that favors tumor cells through chronic inflammation in the patient, including OipA from H. pylori [Xu C, et al. 2020]. Recently, OmpF and OmpC from E. coli have been associated with the ability to form toxic fibrillar aggregates with amyloid properties that could be contributing to the pathogenesis of cancer [Belousov MV, et al. 2023].

In this context, intercellular communication mediated by extracellular vesicles (EVs) has emerged as a key player in cancer pathogenesis, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance. EVs are structures that are commonly spherical in shape with at least one lipid bilayer delimiting them, which include exosomes (originating inside cells) and microvesicles (originating by evagination or protrusion of the plasma membrane). They are released by both healthy cells and tumor cells and are carriers of molecules, facilitating the transfer of biological cargo, such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, between tumor cells and the microenvironment [Becker, S., et al. 2016; Buenafe AC., et al. 2022]. These EVs can be of different sizes; the smallest are called Exosomes and those of different sizes known Polydisperse Extracellular Vesicles (PEVs).

The tumor microenvironment contains PEVs in high concentrations, and it has be observed that these cells are capable of secreting a greater amount of EVs compared to healthy cells [Lopez K et al. 2023]. Furthermore, it has be observed that more aggressive tumor cells secrete a significantly greater quantity and variety of PEVs than less aggressive cells. This increased secretion of PEVs is therefore considered to be a key mechanism by which attractive cancer cells transmit their malignant characteristics and remodel the environment to their advantage [Majood, M., et al. 2022; Balaj et al. 2023; Shetty and Upadhya 2020.].

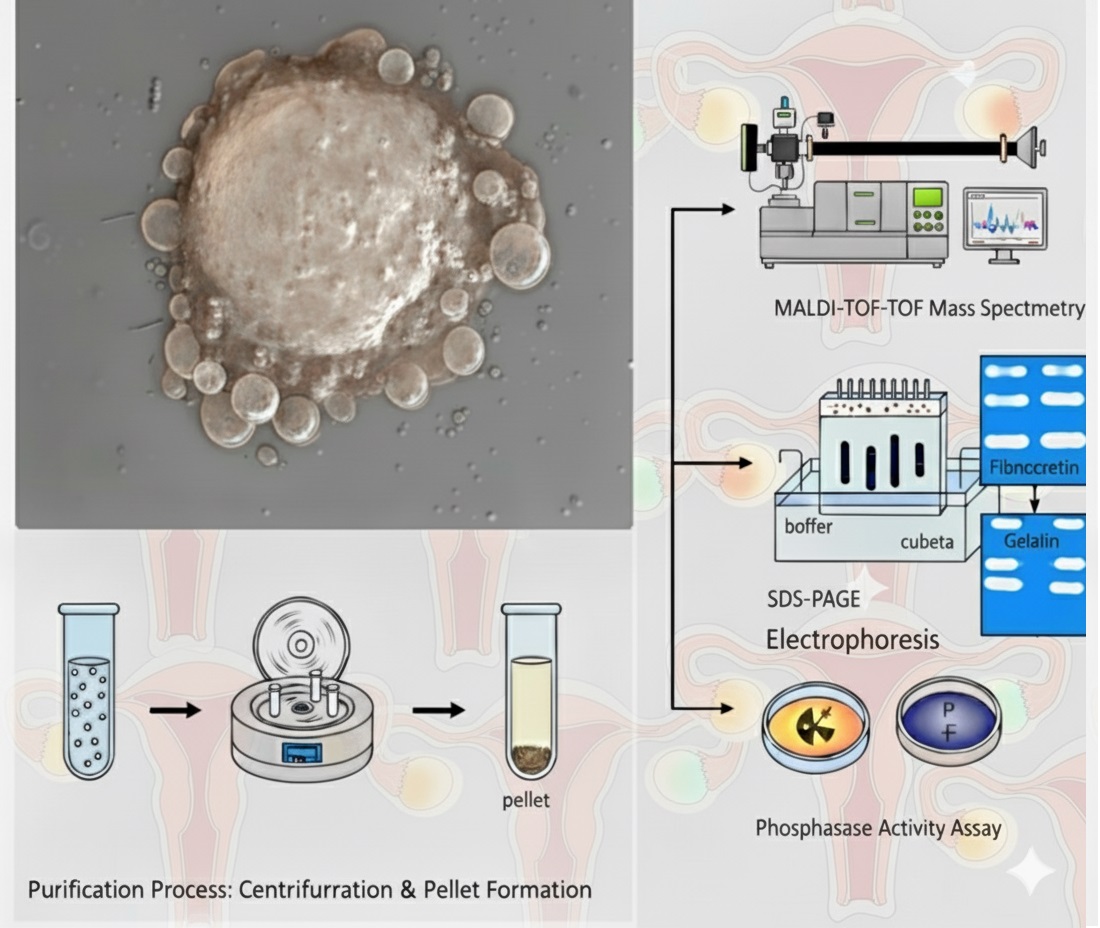

We have previously reported that a fraction of E. coli bacteria is capable of inducing macrophages to release PEVs in abundance in terms of size, with the LMW-PTP (ACP1) protein being used as a marker for them and monitoring them using confocal microscopy when large PVEs are present [Sierra-López et al. 2025]. Therefore, we have used the induction strategy, and this study focuses on investigating whether a fraction of E. coli is capable of inducing PEVs secretion in SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells, which could reflected in the abundance of PEVs, even secreting those that allow monitoring by confocal microscopy. We have also tested the biological activity of PVEs in terms of key functions such as proteolytic activity and phosphatase enzyme activity. Our findings could offer a new perspective on the pathogenesis of this disease and the role of bacterial infections as stimulants to cancer cells with phenotypes related to greater aggressiveness.to cancer cells with phenotypes related to greater aggressiveness.

2. Results

Localization and Quantification of LMW-PTP

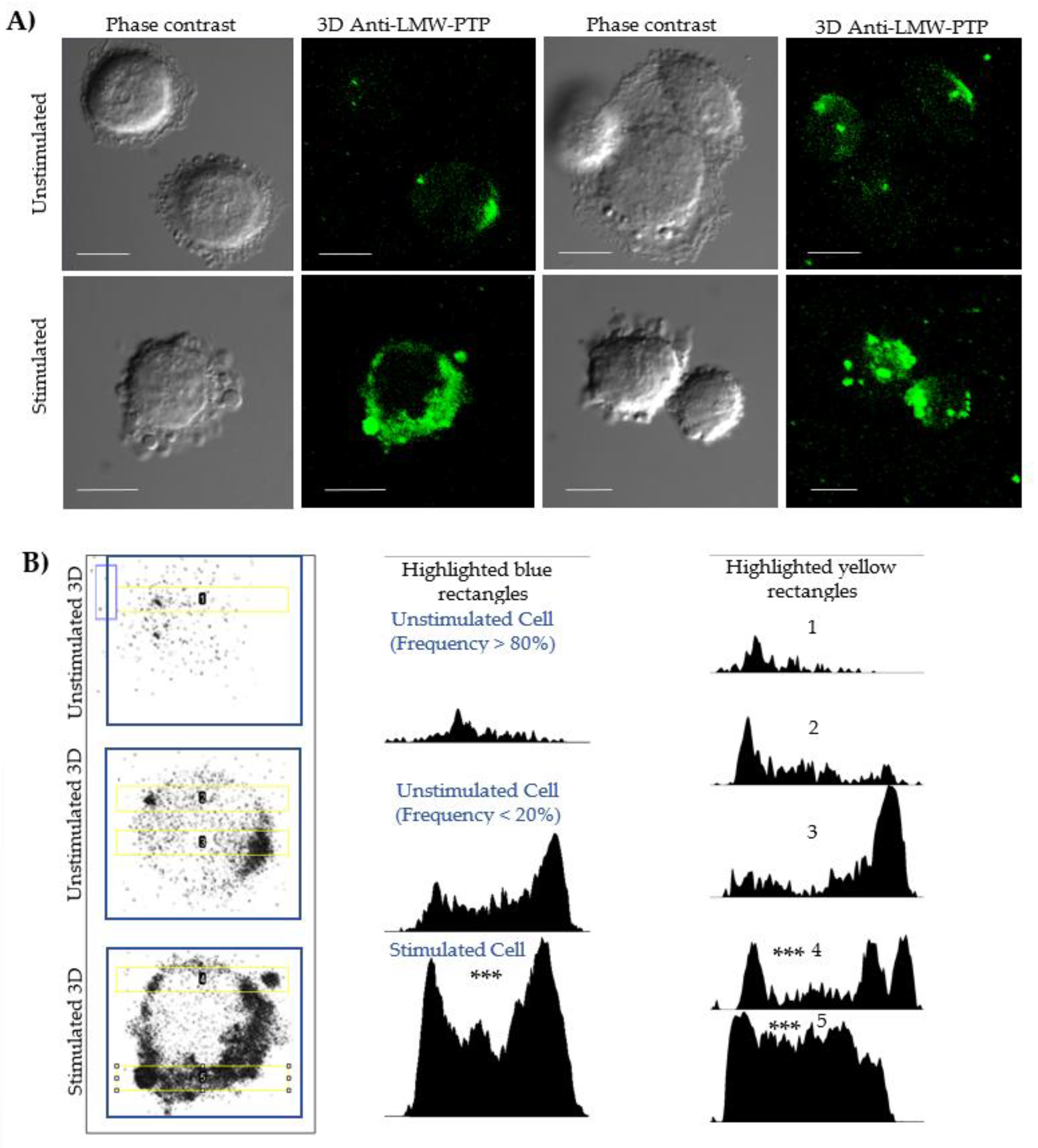

Fluorescence microscopy and densitometry analyses evaluated the localization and increase for protein related to cells and PEVs (

Figure 2). An antibody against LMW-PTP was used because previous studies have shown that this same bacterial fraction induces the secretion of PEVs enriched with this phosphatase in macrophages. In our model, unstimulated cells showed a distribution of LMW-PTP in the cytoplasm, close to the membrane (

Figure 2, Panel B, column 1, row 1), with a polarization that is sometimes more visible in cells (

Figure 2, Panel B, column 1, row 2). Densitometry of unstimulated whole cells (

Figure 2, Panel B, column 2, row 1) showed that they commonly have a low LMW-PTP intensity.

In stimulated SKOV-3 cells (

Figure 2, Panel A, row 2 Stimulated), a significant increase in the number of extracellular vesicles was observed. Although not all vesicles showed labeling, the intensity of LMW-PTP was significantly increased in specific populations, which was reflected in a higher signal intensity in the densitometry of stimulated cells (

Figure 2, Panel B, column 2, row 3). Densitometry analyses in a 20 µm long strip (

Figure 2, Panel B, column 3) validated that the peaks of highest LMW-PTP labeling intensity were coincident with the location of PEVs and the cell periphery and revealed a statistically significantly different pattern comparing the most frequent form of unstimulated cells with stimulated cells secreting PEVs.

3. Discussion

The role of polydisperse extracellular vesicles (PEVs) in intercellular communication and cancer progression is a growing area of research. Traditionally, attention to EVs has focused on the smallest ones originating in multivesicular bodies and released by the endosomal pathway, known as exosomes (30-150 nm) [Xiao Y et al. 2019, Javeed N et al. 2017], followed by EVs released by evagination of the plasma membrane, also known as microvesicles or ectosomes, whose dimensions can vary greatly, from a few tens of nm to several micrometres [Jeppesen D. et al. 2023]. In recent years, it has been shown that cancer cells can release both small and large EVs of several micrometres in size, with characteristics specific to cancer cells, which is why they have also been given the names oncosomes and large oncosomes, due to the role of these populations of PEVs in each group within cancer biology [Minciacchi V. et al. 2015, Jeppesen D. et al. 2023]. In addition, these samples of oncosomes, and mainly large oncosomes, can provide markers for liquid biopsies [Pezzicoli G et al. 2020].

As mentioned in the introduction, some microorganisms can trigger cancer or aggravate it if it is already present when they infect people. These include bacteria, among which species have been found that can enhance carcinogenic effects and create a microenvironment more favourable to cell transformation [Francescone, R., Hou, V., & Garrett, W. S. 2014], increasing cancer progression and metastasis, as is the case with Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer [Kostic, A. D., et al. 2013, Yu, J., et al. 2020, Kudo, S., et al. 2024], Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer [Rizzardi, P., et al. 2020], or increasing inflammatory damage as with Mycoplasma hominis and Chlamydia trachomatis in ovarian cancer [Nishimura, M., et al. 2019, Bandera, E. V., et al. 2010]. Escherichia coli is among the bacterial species in the microbiome that have been suggested to influence cancer development in various tissues [Grivennikov, S. I., et al. 2011; Arthur, J. C., et al. 2012, Davoody, S., et al., 2025], being among the most prevalent Gram-negative bacteria in cancer patients [Taşkın Kafa, B. 2023; E. A. Al-Hajji et al. 2024; E. A. El-Seifi et al. 2019]. Among the molecules and outer membrane proteins of Gram-negative bacteria that aggravate cancer or favour cancer cells in the microenvironment are lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [Mager, D. E. 2006], outer membrane proteins such as OipA [Xu C, et al. 2020], OmpF, OmpC [Belousov MV, et al. 2023]

Our results demonstrate that the fraction we used from the outer membrane of Gram-negative E. coli bacteria contains a mixture of molecules that act as a potent inducer of EV secretion in SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells. We previously described and reported this fraction as a strong inducer of the secretion of a wide variety of polydisperse EVs (PEVs) secreted by macrophages, which contain various porins, among other proteins, and are suggested to contain lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipids (Sierra-López F et al. 2025). It has been documented that LPS is capable of inducing an increase in small EVs (exosomes) from human cells [Bai G et al. 2020]. Likewise, subcellular fractions such as vesicles secreted by bacteria (called ‘outer membrane vesicles’) from Porphyromonas gingivalis [Elsayed R, et al. 2021] and Helicobacter pylori [Wang X, et al. 2024], which contain porins and LPS, are capable of inducing the general secretion of EVs into host cells. Furthermore, in our case, human fibronectin (FN), which was used to stabilise the bacterial stimulus, may have contributed to the response by acting as an adhesion substrate that would facilitate the interaction between SKOV-3 cells and the bacterial fraction of E. coli, helping to observe stimulated cells secreting PEVs at low doses.

A relevant finding of our study is the presence of LMW-PTP phosphatase in some EV populations, which increase in quantity after cell stimulation. This is particularly relevant because the previous study with the same bacterial fraction showed that it induces the production of LMW-PTP-enriched EVs in macrophages and increases the expression of this protein in both the cytoplasm and plasma membrane [Sierra-López F et al. 2025]. The detection of LMW-PTP in some populations or subpopulations of SKOV-3 EVs suggest that the induction of phosphatase and its packaging into vesicles is a conserved response mechanism in different cell types for some EV populations, not limited to immune system cells. This reasoning is supported by the report of the identification of LMW-PTPs in small EVs from colorectal cancer cells [Clerici S et al. 2021].

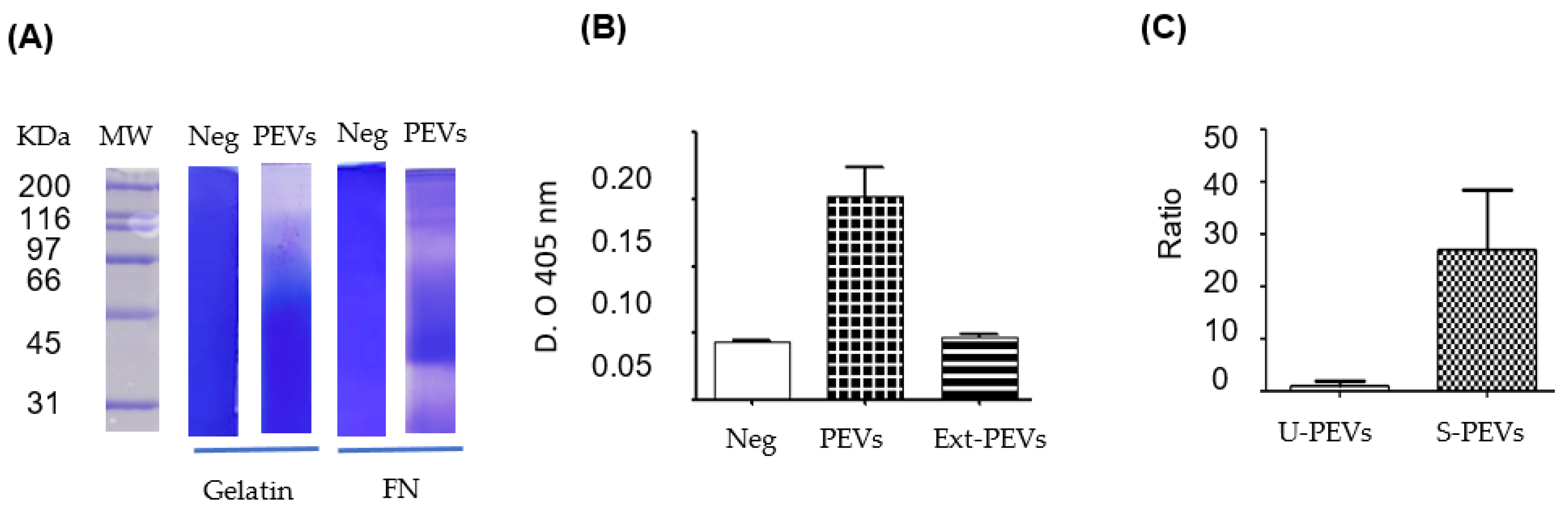

Analysis of the enzymatic activity of EVs revealed a crucial aspect the loss of phosphatase activity when lysing EVs. This phenomenon, coupled with the low ‘Unused’ LMW-PTP in mass spectrometry, suggests that proteases, also encapsulated in EVs, degrade both LMW-PTPs and other enzymes once the vesicular membrane is broken or when the integrity of the EVs is lost. Therefore, these EVs are not simply a transport vehicle, but a protective compartment that maintains an order that allows enzymes susceptible to degradation to be maintained in the extracellular microenvironment. The self-degradation of proteins in total extracts from some EV populations by their own proteases is an event that has been documented [Fochtman D et al. 2024].

The detailed proteomic profile of EVs shows the presence of proteins associated with the cytoskeleton and vesicular biogenesis, such as actin, vimentin, annexins, and clathrin, supporting the idea that a portion of the mixture of EV-like particles are formed by the evagination of ectosomes or microvesicles from the plasma membrane. The identification of glycolytic enzymes (such as pyruvate kinase and alpha-enolase) and heat shock proteins (HSP70/90) in EVs suggests a possible state of metabolic stress in SKOV-3 cells, as has been observed in other cancer cells [Kumar M et al. 2024]. The presence of fibronectin in EVs could be explained by the internalisation of substrate fibronectin by SKOV-3 cells, which loaded the glycoprotein into EVs, or by the fact that once secreted, EVs captured it from the cell culture surface where it was located together with the stimulus. The uptake and incorporation of proteins from the extracellular medium into EVs has been previously documented [Elsharkasy O et al. 2025, Sung B et al. 2025]. Additionally, the detection of albumin in EVs can be explained by the fact that the cells, previously cultured in a medium with foetal bovine serum, internalized and stored albumin, and subsequently released a portion of it by encapsulating it in EVs during stimulation in a serum-free medium.

The co-presence of proteases and phosphatases in EVs suggests a complex bioactive machinery whose purpose appears to be both the modification of the tumors microenvironment and the modification of the basal state of the host cells with which they come into contact. In addition to LMW-PTPs, other enzymes could be contributing to the phosphatase activity observed on para-nitrophenol phosphate, such as alkaline phosphatase.

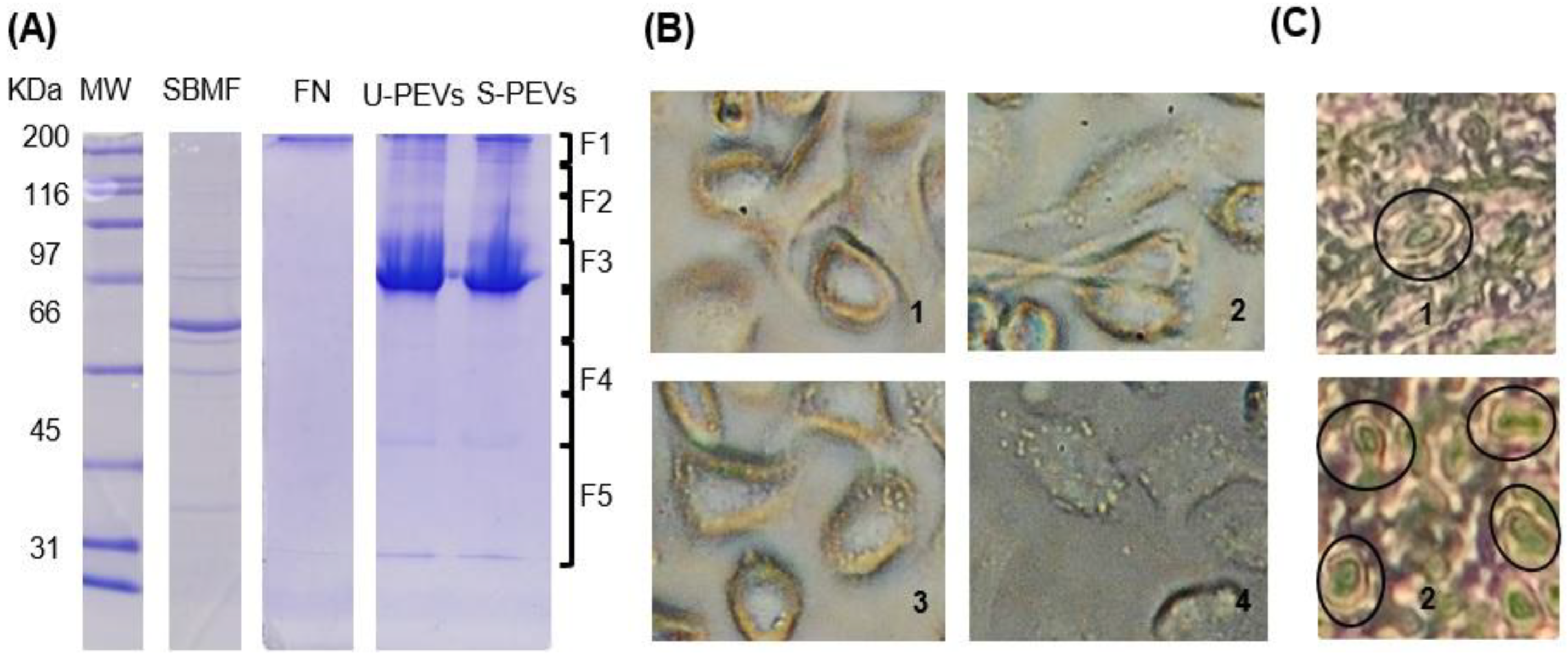

Our findings, derived from the in vitro model we used, are significantly reinforced by observations of histological sections of ovarian tissue using an inverted microscope, where we distinguished the presence of cells with protrusions similar in appearance to the large EVs we observed anchored to the surface of stimulated SKOV-3 cells. This was detected rarely and with difficulty in healthy ovaries, while it was easier to find several cells with these characteristics in samples of ovarian cancer diagnosed as serous papillary cystadenocarcinoma, suggesting that this phenomenon of large EV secretion (large oncosomes) occurs naturally in vivo, increasing in tumors tissue. This parallelism is vital, as it indicates that vesicles are not merely a cell culture artefact, but could play a role in the biology of ovarian cancer, possibly in tumors progression and dissemination. To date, few studies have focused on evaluating or reporting the possibility of observing large oncosomes in histological sections. One such study corresponds to prostate cancer, in which these large EVs were only observed in tumors tissue sections and not in healthy tissue [Di Vizio D et al. 2012], and in lung tumors tissue [Minciacchi V. et al. 2015].

4. Materials and Methods

Human Samples for Assays

All samples were taken at the hospital stay. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad de Ixtapaluca, “IMSS-Bienestar” (NR-017-2025).

Cell Culture

The SKOV-3 (ATCC-HTB-77) reference cell line was used. In brief, cell culture was performed in McCoy’s 5A medium (Corning, 10-050-CVR) at 37 °C and 5% CO₂. Furthermore, for continuous maintenance of the medium, it was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Corning) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PAA, P11-010), as described previously (Alberto-Aguilar et al. 2022). BFS was not used during polydisperse extracellular vesicle (PEV) secretion stimulations. Extraction of Escherichia coli Fraction

Standardization of SKOV-3 PEV (Short and Large) Secretion and Isolation

Within in brief, glass coverslips or plastic surfaces coated per cm² with a mixture of 0.250 µg of human fibronectin (FN) and 20 ng of dialyzed SDS-SBMF protein were used. The surfaces were prepared and the FN obtained as indicated in Sierra-López et al. 2025. No stimulant was placed as a negative control. SKOV-3 cells were deposited at a ratio of 4 × 10⁴/cm² together with sufficient McCoy’s 5A medium with L-glutamine (Corning, 10-50-CV, USA) to coat the cultures without FBS. The cells were monitored under an inverted microscope, and after 120 min of interaction, the supernatant with the EVs was collected or fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 45 min for confocal microscopy assays. For SDS-PAGE, zimogram, and enzyme activity assays, EVs were isolated from cultures in 10 cm diameter Petri dishes containing 15 mL of initial medium, collecting 14 mL of supernatant after 2 hours of interaction, the contaminating cells were then discarded together with 500 µL of contiguous supernatant by centrifuging at 120×g for 5 min in 15 mL tubes. The VE mix was precipitated with 0.2 mM ZnSO4 at 16,000×g for 20 min using 1.5 mL conical tubes (Centrifuge Eppendorf 5415C).

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

The samples were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE (Towbin et al. 1979) and visualized by Coomassie blue or electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 80 V. A total of 8 µL of β-mercaptoethanol, SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor were added to each sample, which were then immediately boiled in a water bath for 8 min, followed by the addition of 8 µL of β-mercaptoethanol and basicification using a 1M NaOH stock solution, as indicated in Sierra-López et al. 2021. Nitrocellulose Western blots (WBs) were incubated with mouse anti-human-LMW-PTP polyclonal antibodies at a dilution of 1:1000 (obtained from Sierra-López et al. 2025). Goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:4000 in TBST was used as the secondary antibody. WBs were developed with the NBT/BCIP kit (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA).

Confocal Microscopy

SKOV-3 cells, either unstimulated or stimulated for 120 min with FN-SDS-SBMF on glass coverslips, were fixed with 4% p-formaldehyde in PBS for 45 min at 37 °C; they were gently washed with PBS and processed at room temperature. Permebilization was performed with 0.0015% SDS and 0.0006% Triton X-100 in PBS for 8 min as indicated in Sierra-López et al. 2025 to reduce EV decoupling. Samples were blocked with 5% BFS, washed with PBS, and incubated with anti-human-LMW-PTPs (1:300) in PBS for 1 h. They were then washed and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse as a secondary antibody (Zymed 1:300) for 1 h. Samples were preserved using Vectashield Antifade Reagent (Vector, Newark, CA, USA), examined with a Carl Zeiss LMS 700 confocal microscope, and processed with ZEN Blue 3.5 (Zeiss, White Plains, NY, USA). Green color was used to represent LMW-PTP loaded in EVs in the analysis with ImageJ2 (version 2.16.0) EVAnalyzer plugin (ImageJ/Fiji).Liquid Chromatography and MALDI-MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography and MALDI-MS/MS

Extracts from stimulated SKOV-3 cell EVs were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, and fragments between 10-200 kDa were processed at the Genomics, Proteomics, and Metabolomic Service of LaNSE (CINVESTAV IPN), according to the modified Shevchenko protocol (Shevchenko et al. 2006), the method modified by Barrera-Rojas et al., 2018 (Barrera-Rojas et al. 2018) and as worked on in Sierra-López et al. 2025. The results of MS/MS spectra were compared using Protein Pilot v.2.0.1 (ABSciex, Framingham, MA, USA) and the Paragon algorithm (Shilov et al. 2007) against Homo sapiens (Uniprot, 67,493 protein sequences database). The detection threshold was 1.3 to ensure 95% confidence. The identified proteins were grouped using the ProGroup algorithm to minimise redundancy. The profile and protein composition of the Escherichia coli SDS-SBMF bacteria fraction was published in Sierra-López et al. 2025.

Proteolytic Activity

Zymograms were performed to analyze the proteolytic activity of the EV mix using gelatin and fibronectin as substrates. EVs were prepared as previously described, avoiding heat denaturation and without β-ME, and were suspended with the standard loading buffer (glycerol, 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, SDS). Subsequently, 10 µg of EVs were separated by electrophoresis on standard 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (distilled water; acrylamide/bisacrylamide; 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8; SDS; ammonium persulfate; and TEMED) copolymerized with 0.4% pork skin gelatin (Sigma G2500, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or 100 µg human fibronectin, performing electrophoretic migration at 4°C without reducing agent. The gels were washed with 1% Triton X-100 for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 37 °C in a developing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM CaCl₂, pH 7.0). The zymograms were stained with Coomassie blue; unstained areas indicated proteolytic activity.

Statistical Analysis

Confocal analysis of PEVs secretion by SKOV-3 cells was performed using Fiji and the EV Analyzer plugin (version 8.1.3 beta). Function: PEVs count; identical thresholds: 10; threshold method: ‘Li’; min circularity: 0.5; filter type: PEV-GFP (to FITC channel); particle size range: 1–999,999. Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 Software: One-way Anova Bonferroni post-test.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our findings suggest a mechanism in which the bacterial fraction stimulates the formation and secretion of extracellular vesicles. These PEVs act as vehicles that transport complex and protected enzymatic machinery, which modifies the extracellular matrix (evidenced by the degradation of fibronectin) and can promote cell migration, which correlates with the elongated morphology we observed in stimulated cells. This mechanism could play a significant role in the progression and spread of ovarian cancer, which is likely to increase in patients suffering from infections with bacteria that express molecules that stimulate PEVs secretion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: F.S.-L., JC.F-H., M.S.-M., JL.R.-E., P.T.-R., G.A.-A. Performed the experiments: F.S.-L., JC.H.-F., M.S.-M., L.B.-P., VI.H.-R. S.B.-H. Analyzed the data: F.S.-L., J.L.R-E., M.S-M., P.T.-R., V.I.-V., G.A-A., S.B-H., JC. B.-A., D.M.-E. Contributed reagents/material/analysis tools: J.L.R.-R., P.T.-R., M.S.-M., F.S-L. G.A.-A. Wrote the paper: F.S.-L., M.S.-M., J.L.R.-E., JC.H.-F.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Consejo Nacional de Humanidades Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCyT), Mexico (Grant 104119), to J.L.R.-E. Doctoral thesis work of F.S.-L. At CINVESTAV-IPN, from which he was the beneficiary of a Ph.D. fellowship from CONAHCyT, México (#362402).

Informed Consent Statement

The research protocol for obtaining anti-LMW-PTP immune sera from mice were approved by the Internal Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (CICUAL) and Biosafety, Genetically modified organism and Pathogens Committee of the Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados (CINVESTAV) with registration number 0216-16 approval date: 17 November 2016. The study in Humans was approved by the Research, Biosafety and Ethics Committee of the Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad de Ixtapaluca. IMSS-Bienestar approval with registration number NR-017-2025.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Acknowledgments

To Emmanuel Ríos Castro for assistance in the protein detection using MALDI Ekspot and MALDI-TOF/TOF 4800 plus mass spectrometer (MS) in the UGPM LaNSE CINVESTAV. Magdalena Miranda Sánchez for her technical assistance in confocal microscopy and Juan Carlos Osorio Trujillo for his assistance with cell line maintenance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Evs |

Extracellular vesicles |

| PEVs |

Polydisperse Extracellular Vesicles |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| SKOV-3 |

Human ovarian cancer cell line |

| SBMF- SDS |

SDS-soluble bacterial membrane fraction |

| LMW-PTP |

Low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase |

| MALDI-MS/MS |

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry |

| OC |

Ovarian cancer |

| FN |

Fibronectin |

| Omp |

Outer membrane protein |

References

- Jayson, G. C.; Kohn, E.; Kitchener, H. C.; Plugge, L.; Kaye, S. B. Ovarian cancer. Lancet 2014, 384 (9945), 1376–1388. [CrossRef]

- Lheureux, S.; Braunstein, M.; Oza, A. M.; Kohn, E. C. Epithelial ovarian cancer: a comprehensive review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111 (11), 1122–1133.

- Becker A, Thakur BK, Weiss JM, Kim HS, Peinado H, Lyden D. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: Cell-to-Cell Mediators of Metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2016 Dec 12;30(6):836-848. [CrossRef]

- Buenafe AC, Dorrell C, Reddy AP, Klimek J, Marks DL. Proteomic analysis distinguishes extracellular vesicles produced by cancerous versus healthy pancreatic organoids. Sci Rep. 2022 Mar 3;12(1):3556. [CrossRef]

- Francescone R, Hou V, Grivennikov SI. Microbiome, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer J. 2014 May-Jun;20(3):181-9. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J. C.; Pérez-Chanona, E.; Mühlbauer, M.; Tomkovich, S.; Uronis, J. M.; Fan, T. J.; Campbell, B. J.; Abujamel, T.; Dogan, B.; Rogers, A. B.; Rhodes, J. M.; Stintzi, A.; Simpson, K. W.; Hansen, J. J.; Keku, T. O.; Fodor, A. A.; Jobin, C. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012, 338 (6103), 120–123. [CrossRef]

- Sierra-López F, Iglesias-Vazquez V, Baylon-Pacheco L, Ríos-Castro E, Osorio-Trujillo JC, Lagunes-Guillén A, Chávez-Munguía B, Hernández SB, Acosta-Altamirano G, Talamás-Rohana P, Rosales-Encina JL, Sierra-Martínez M. A Fraction of Escherichia coli Bacteria Induces an Increase in the Secretion of Extracellular Vesicle Polydispersity in Macrophages: Possible Involvement of Secreted EVs in the Diagnosis of COVID-19 with Bacterial Coinfections. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Apr 16;26(8):3741. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt AP, Redinbo MR, Bultman SJ. The role of the microbiome in cancer development and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Jul 8;67(4):326-344. [CrossRef]

- Kostic A. D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J. N.; Gallini, C. A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T. E.; Chung, D. C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G. L.; El-Omar, E. M.; Brenner, D.; Fuchs, C. S.; Meyerson, M.; Garrett, W. S. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumoral-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe, 2013, 14(2), 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Shen J, Xu Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Colorectal Cancer. Infect Drug Resist. 2022 Mar 17;15:1115-1120. [CrossRef]

- Duizer C, Salomons M, van Gogh M, Gräve S, Schaafsma FA, Stok MJ, Sijbranda M, Kumarasamy Sivasamy R, Willems RJL, de Zoete MR. Fusobacterium nucleatum upregulates the immune inhibitory receptor PD-L1 in colorectal cancer cells via the activation of ALPK1. Gut Microbes. 2025 Dec;17(1):2458203. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, M., et al. “Mycoplasma hominis and Chlamydia trachomatis in ovarian cancer.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, vol. 45, no. 1, 2019, pp. 121-127.

- Bandera, E. V., et al. “Reproductive and hormonal factors and risk of ovarian cancer.” Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 22, no. 1, 2010, pp. 24-30.

- Geller, R., et al. “The female genital tract microbiome and its association with ovarian cancer risk.” International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, vol. 32, no. 8, 2022, pp. 1045-1052.

- Rizzardi, P., et al. (2020). The Microbiome and Cancer: An Update. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 73(6), 297-302.

- Arthur, J. C.; Pérez-Chanona, E.; Mühlbauer, M.; Tomkovich, S.; Uronis, J. M.; Fan, T. J.; Campbell, B. J.; Abujamel, T.; Dogan, B.; Rogers, A. B.; Rhodes, J. M.; Stintzi, A.; Simpson, K. W.; Hansen, J. J.; Keku, T. O.; Fodor, A. A.; Jobin, C. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012, 338 (6103), 120–123. [CrossRef]

- Liu CH, Chen Z, Chen K, Liao FT, Chung CE, Liu X, Lin YC, Keohavong P, Leikauf GD, Di YP. Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Chronic Inflammation Promotes Tobacco Carcinogen-Induced Lung Cancer and Determines the Efficacy of Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2021 Jan 1;81(1):144-157. [CrossRef]

- Taşkın Kafa, A. H.; Çubuk, F.; Hasbek, M.; Aslan, R.; Çubuk, Z. Distribution of microorganisms isolated from blood cultures and evaluation of antibiotic resistance rates in patients diagnosed with cancer. J. Clin. Pract. Res. 2023, 45 (4), 370–376. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Al-Hajji et al. (2024). Bloodstream infections in pediatric hematology/oncology patients: a single-center study in Wuhan. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024 Dec 4;14:1480952. [CrossRef]

- E. A. El-Seifi et al. (2019). Escherichia coli Bloodstream Infections in Patients at a University Hospital: Virulence Factors and Clinical Characteristics. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019 Jun 6;9:191. [CrossRef]

- Xu C, Soyfoo DM, Wu Y, Xu S. Virulence of Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins: an updated review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;39(10):1821-1830. [CrossRef]

- Belousov MV, Kosolapova AO, Fayoud H, Sulatsky MI, Sulatskaya AI, Romanenko MN, Bobylev AG, Antonets KS, Nizhnikov AA. OmpC and OmpF Outer Membrane Proteins of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica Form Bona Fide Amyloids. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Oct 24;24(21):15522. [CrossRef]

- Lopez K, Lai SWT, Lopez Gonzalez EJ, Dávila RG, Shuck SC. Extracellular vesicles: A dive into their role in the tumor microenvironment and cancer progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023 Mar 21;11:1154576. [CrossRef]

- Majood M, Rawat S, Mohanty S. Delineating the role of extracellular vesicles in cancer metastasis: A comprehensive review. Front Immunol. 2022 Aug 19;13:966661. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Y, Zheng L, Zou X, Wang J, Zhong J, Zhong T. Extracellular vesicles in type 2 diabetes mellitus: key roles in pathogenesis, complications, and therapy. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019 Jun 14;8(1):1625677. [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen DK, Zhang Q, Franklin JL, Coffey RJ. Extracellular vesicles and nanoparticles: emerging complexities. Trends Cell Biol. 2023 Aug;33(8):667-681. [CrossRef]

- Javeed N, Mukhopadhyay D. Exosomes and their role in the micro-/macro-environment: a comprehensive review. J Biomed Res. 2017 Sep 26;31(5):386-394. [CrossRef]

- Minciacchi VR, You S, Spinelli C, Morley S, Zandian M, Aspuria PJ, Cavallini L, Ciardiello C, Reis Sobreiro M, Morello M, Kharmate G, Jang SC, Kim DK, Hosseini-Beheshti E, Tomlinson Guns E, Gleave M, Gho YS, Mathivanan S, Yang W, Freeman MR, Di Vizio D. Large oncosomes contain distinct protein cargo and represent a separate functional class of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles. Oncotarget. 2015 May 10;6(13):11327-41. [CrossRef]

- Pezzicoli G, Tucci M, Lovero D, Silvestris F, Porta C, Mannavola F. Large Extracellular Vesicles-A New Frontier of Liquid Biopsy in Oncology. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Sep 7;21(18):6543. [CrossRef]

- Elsayed R, Elashiry M, Liu Y, El-Awady A, Hamrick M, Cutler CW. Porphyromonas gingivalis Provokes Exosome Secretion and Paracrine Immune Senescence in Bystander Dendritic Cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 Jun 1;11:669989. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Wang J, Mao L, Yao Y. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane vesicles and infected cell exosomes: new players in host immune modulation and pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2024 Dec 13;15:1512935. [CrossRef]

- Clerici SP, Peppelenbosch M, Fuhler G, Consonni SR, Ferreira-Halder CV. Colorectal Cancer Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Educate Human Fibroblasts to Stimulate Migratory Capacity. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Jul 15;9:696373. [CrossRef]

- Davoody S, Tayebi Z, Sharif-Zak M, Azizmohammad Looha M, Mortezaei Ferizhandy N, Sadeghi Mofrad S, Houri H. Assessing the role of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in colorectal cancer oncogene expression: insights from microbial colonization phenotypes. Mol Biol Rep. 2025 Aug 15;52(1):828. [CrossRef]

- Fochtman D, Marczak L, Pietrowska M, Wojakowska A. Challenges of MS-based small extracellular vesicles proteomics. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 Dec;13(12):e70020. [CrossRef]

- Kumar MA, Baba SK, Sadida HQ, Marzooqi SA, Jerobin J, Altemani FH, Algehainy N, Alanazi MA, Abou-Samra AB, Kumar R, Al-Shabeeb Akil AS, Macha MA, Mir R, Bhat AA. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Feb 5;9(1):27. [CrossRef]

- Elsharkasy OM, de Voogt WS, Tognoli ML, van der Werff L, Gitz-Francois JJ, Seinen CW, Schiffelers RM, de Jong OG, Vader P. Integrin beta 1 and fibronectin mediate extracellular vesicle uptake and functional RNA delivery. J Biol Chem. 2025 Mar;301(3):108305. [CrossRef]

- Sung BH, Emmanuel M, Gari MK, Guerrero JF, Virumbrales-Muñoz M, Inman D, Krystofiak E, Rapraeger AC, Ponik SM, Weaver AM. Exosomes are specialized vehicles to induce fibronectin assembly. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Jun 24:2025.06.23.661091. [CrossRef]

- Di Vizio D, Morello M, Dudley AC, Schow PW, Adam RM, Morley S, Mulholland D, Rotinen M, Hager MH, Insabato L, Moses MA, Demichelis F, Lisanti MP, Wu H, Klagsbrun M, Bhowmick NA, Rubin MA, D’Souza-Schorey C, Freeman MR. Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am J Pathol. 2012 Nov;181(5):1573-84. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).