1. Introduction

The design of neuromorphic systems is traditionally framed as a trade-off between biological plausibility and computational efficiency [

1]. Biophysically detailed neuron models, such as Hodgkin–Huxley [

2], reproduce the ionic and membrane dynamics of real neurons with high fidelity, but at the cost of substantial computational and hardware complexity [

2,

3]. At the opposite extreme, the abstract neurons used in second-generation artificial neural networks (ANNs), rooted in the McCulloch–Pitts model [

5] and later refined through nonlinear activation functions [

6] and backpropagation [

4], favor mathematical simplicity and have enabled the success of deep learning, but discard the temporal and event-driven nature of neural computation.

Spiking neural networks (SNNs) occupy an intermediate position by encoding information in the timing of discrete spike events [

5]. This event-driven paradigm supports sparse communication, massive parallelism, and in-memory computation, which are key to the remarkable energy efficiency of biological nervous systems and to neuromorphic hardware platforms [

6]. However, most widely used spiking neuron models, including Izhikevich’s [

7] and Hodgkin–Huxley–based formulations, still rely internally on high-precision continuous-state variables and arithmetic-intensive operations, particularly multiplications. While effective in software, this reliance on complex arithmetic severely limits their scalability and efficiency in digital hardware [

8].

Rather than viewing spiking computation primarily through the lens of biological realism, an alternative perspective is to treat spikes as a computational format for representing and processing temporal information. In this view, the fundamental variable is not a continuous membrane voltage but the timing of discrete events. A particularly efficient temporal coding scheme is the inter-spike interval (ISI), in which information is represented by the time difference

between consecutive spikes. As illustrated in

Figure 1, ISI coding can be implemented either within a single neuron or across a population, enabling both compact and distributed temporal representations.

In conventional spiking neuron models, spike timing emerges from the evolution of an analog or high-precision state variable that crosses a threshold. In such systems, small numerical errors in the internal state can translate into large timing errors in the output spike train. An alternative is to generate spike timing directly from the dynamics of a discrete-time system. When spike timing is governed by a quantized IIR-like state evolution, temporal precision becomes primarily a function of the system clock and filter dynamics rather than of numerical resolution, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The ISI format is advantageous not only due to its sparsity—fewer spike events result in reduced power consumption—but also for its compatibility with digital hardware and control systems. At the network output, ISI-encoded signals can be used directly for classification via time-to-first-spike decoding, or converted into pulse-width modulation (PWM) signals for continuous control, as shown in

Figure 3. This enables end-to-end spike-based pipelines that interface naturally with sensors and actuators without requiring expensive analog-to-digital or floating-point processing stages.

In many spiking systems, decision making can be naturally expressed in terms of time-to-first-spike: in a population of output neurons, the neuron that fires first represents the selected class. This temporal winner-takes-all mechanism is well suited to event-driven hardware, as it avoids the need for explicit normalization or high-precision accumulation.

More generally, SNNs can be interpreted as cascaded timing systems. Neurons in intermediate layers are not required to fire first, but to fire at the appropriate time so as to activate downstream neurons. The final layer then implements a temporal competition, transforming distributed spike timing into a discrete decision.

Conventional ANNs and many SNN models propagate information between layers in the form of numerical intensities, whether as real-valued activations, spike counts, or firing rates. Even when spikes are used, neurons typically integrate these signals to reconstruct an analog quantity before deciding whether to emit a new spike.

In contrast, the paradigm explored in this work is fundamentally temporal. Neurons do not attempt to transmit intensities to downstream layers. Instead, they aim to emit spikes at the correct time so as to trigger subsequent neurons at their own appropriate times. Computation emerges from the interaction between internal dynamics and the relative timing of incoming spikes, rather than from the accumulation of signal magnitude.

From this perspective, spikes and ISI codes form a computational abstraction for temporal signal processing rather than merely a biological metaphor. This view opens the possibility of designing spiking neurons as discrete-time dynamical systems optimized directly for digital hardware.

This work introduces the Spike Processing Unit (SPU), a spiking neuron model designed from the outset as a low-precision, multiplier-free, discrete-time system. The SPU implements second-order IIR dynamics on 6-bit signed state variables and generates output spikes when its internal state crosses a threshold. Temporal selectivity and spike timing arise from filter dynamics rather than from analog state precision.

Figure 4 provides a qualitative comparison of representative neuron models from this hardware-oriented viewpoint. While biophysically detailed and simplified spiking models emphasize biological fidelity and rich internal dynamics, the SPU prioritizes arithmetic simplicity, quantization robustness, and hardware implementability, while retaining sufficient temporal dynamics for meaningful spike-based computation.

The remainder of this paper presents the SPU architecture, its discrete-time operational principles, and its training for temporal pattern discrimination. Through simulation and hardware synthesis, we show that meaningful spiking computation can be achieved with extremely low numerical precision and without multipliers, enabling a new class of temporally expressive yet highly efficient neuromorphic building blocks.

2. The Spike Processing Unit (SPU) Model

This section introduces the architecture and operational principles of the Spike Processing Unit (SPU), a spiking neuron model based on discrete-time dynamical systems. The SPU implements neuronal computation as a low-order Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter driven by spike events, allowing temporal information to be processed directly in the time domain.

This formulation naturally leads to a highly efficient digital realization: by constraining the filter coefficients and internal state to low-precision, power-of-two representations, the SPU eliminates the need for multipliers and reduces hardware complexity. However, this efficiency is a consequence of the underlying temporal computing paradigm rather than its primary objective.

2.1. Model Overview and Computational Philosophy

The design of the Spike Processing Unit (SPU) is guided by a fundamental hypothesis: that maximal hardware efficiency in neuromorphic systems is more effectively achieved through a functional abstraction of neural computation than through incremental approximations of biological fidelity. This philosophy prioritizes the preservation of computational roles—such as temporal integration, thresholding, and spike-based communication—while deliberately discarding biologically inspired but computationally expensive mechanisms.

The SPU embodies this principle by replicating the computational role of a biological neuron rather than its detailed biological mechanics. It receives spike events at its inputs, processes them through a discrete-time dynamical system implemented as an Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter, and generates an output spike when an internal state variable crosses a threshold. This internal state plays the role of a membrane potential, but it is fundamentally a digital, discrete-time signal whose purpose is to shape spike timing rather than to represent an analog voltage.

The key innovation of this architecture—beyond its conceptual shift—is the constraint of all IIR filter coefficients to powers of two. This critical design choice enables the replacement of arithmetic multipliers with low-cost bit-shift operations. When combined with 6-bit two’s complement integer arithmetic and inter-spike interval (ISI) based temporal coding, the SPU becomes entirely multiplier-free and inherently optimized for efficient digital hardware implementation.

Figure 5 provides a high-level block diagram of the SPU’s architecture, while

Figure 6 details the second-order IIR filter that forms its computational core.

The SPU (

Figure 5) can be scaled to include as many synapses as required by adding more synapse modules and summing nodes to the

soma (SPU’s body).

The clock signal, CK, defines the discrete-time resolution of the neuron. While all SPUs typically operate under a common clock in hardware, the effective temporal behavior of each neuron is governed by its IIR coefficients, which determine its time constants, damping, and resonance. In this way, neurons with distinct temporal characteristics can be realized without changing the clock frequency, purely through their internal dynamics.

2.2. Synaptic Input and Weighted Summation

The SPU features

M synaptic inputs. Each synapse has an associated weight

, stored as a 6-bit two’s complement integer. At each discrete time step

n, the total synaptic drive

is obtained by summing the weights of all synapses that received a spike during that clock cycle:

where

indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of a spike on synapse

m at time

n.

Although Equation (

1) is written in multiplicative form, no physical multiplication is performed in hardware. Since

is binary, each synapse either contributes its weight to the sum or contributes nothing. The operation therefore reduces to a set of conditional additions, which are substantially cheaper and more energy-efficient than arithmetic multipliers.

From a hardware perspective, each synapse acts as an event-controlled gate: when a spike arrives, its stored weight value is presented to the summation node; when no spike is present, the synapse contributes zero. The resulting is sampled by the SPU soma at the rising edge of the clock.

In this way, synaptic processing is intrinsically event-driven. The arrival time of spikes determines which weights are injected into the IIR dynamics at each clock cycle, directly shaping the temporal evolution of the membrane potential rather than representing an accumulated signal amplitude.

2.3. IIR Filter as Membrane Dynamics

The core of the SPU is a second-order IIR filter (

Figure 6), which computes the discrete-time membrane potential

as a function of current and past synaptic inputs and of its own past state:

The coefficients

and

are restricted to the discrete set

. Because these values are exact powers of two, all multiplications in Equation (

2) are implemented in hardware using arithmetic bit shifts and additions or subtractions. No general-purpose multipliers, lookup tables, or approximations are involved.

This constraint preserves the mathematical form of the IIR filter while making its implementation exceptionally compact and energy-efficient. The filter coefficients control the location of poles and zeros, and therefore directly determine properties such as damping, resonance, and stability. As a result, the temporal behavior of the SPU—including oscillations, decay rates, and frequency selectivity—can be predicted and tuned using standard discrete-time signal processing theory.

By expressing membrane dynamics in this IIR form, the SPU replaces nonlinear differential equations with a linear, well-understood dynamical system whose behavior is both analyzable and hardware-realizable under strict low-precision constraints.

2.4. Spike Generation and Reset Mechanism

An output spike

is generated at discrete time

n whenever the membrane potential

exceeds a programmable threshold

:

This operation is implemented by a digital comparator associated with a register holding .

Unlike classical spiking neuron models, the SPU does not employ an explicit membrane reset after a spike. Instead, its post-spike behavior is entirely governed by the intrinsic dynamics of the IIR filter. Depending on the filter coefficients and on the current internal state, the membrane potential may decay, oscillate, remain elevated, or immediately cross threshold again. As a result, a single input spike may already trigger an output spike, while in other configurations multiple spikes may be required, or even fail to produce a spike at all. Spiking is therefore not tied to a fixed integration-and-reset cycle, but emerges from the interaction between incoming events and the filter’s impulse response.

This mechanism enables the SPU to process information encoded in spike timing relative to its internal dynamical state. An early spike can excite the filter and set its internal phase, while later spikes interact with this evolving state to either promote or suppress a threshold crossing. In this sense, each SPU possesses an intrinsic form of short-term memory: the effect of a spike depends not only on its weight, but also on when it arrives relative to the current state of the IIR dynamics.

The behavior illustrated in

Figure 7 highlights a key departure from conventional excitatory/inhibitory synapse models: in the SPU, a spike can effectively act as excitatory or inhibitory depending on when it arrives. A spike may push the internal state toward threshold, drive it into a subthreshold oscillation, or move it into a refractory-like regime that suppresses subsequent firing. This temporal context dependence is a direct consequence of the IIR dynamics and is central to the SPU’s computational expressiveness.

A digital reset signal (RST in

Figure 5) is nevertheless provided for system-level control, such as initialization or the implementation of global inhibitory mechanisms (e.g., winner-takes-all strategies). This reset does not participate in the neuron’s intrinsic computation and is not required for normal spiking operation; it merely offers an external means to force the internal state to a known baseline when needed by the surrounding architecture.

2.5. Information Representation and Hardware-Optimized Precision

A fundamental choice in neuromorphic engineering is how information is represented and propagated through a network. The SPU adopts a strictly temporal view of computation, in which information is carried by the timing of spike events, combined with a deliberately low-precision internal numerical representation to enable efficient digital implementation.

2.5.1. Temporal Coding and Spike Timing

The SPU communicates exclusively through spike events. At the network interfaces, information can be encoded and decoded using inter-spike intervals (ISI), spike latency, or winner-takes-all timing, as illustrated in

Section 1. In these contexts, temporal differences between spikes provide a convenient way to represent analog quantities for sensing, actuation, or classification.

Internally, however, the SPU does not operate on explicit ISI values. Computation is driven by spike timing relative to the neuron’s evolving internal state. Each incoming spike interacts with the current IIR filter state, and this interaction may push the neuron closer to threshold, drive it into a subthreshold oscillation, or move it into a refractory-like regime. Consequently, information processing depends on when a spike arrives, not on the explicit time difference between pairs of spikes.

In this sense, the SPU implements a form of temporal coincidence-based computation: meaningful computation emerges from the alignment between spike arrival times and the internal phase of the IIR dynamics. Temporal relations are preserved, but no explicit numerical time measurements are required.

2.5.2. Low-Precision Integer Arithmetic

All internal arithmetic in the SPU is performed using 6-bit two’s complement signed integers with explicit saturation. All adders clamp their outputs to the range to prevent wrap-around and to guarantee bounded dynamics. This saturation is not an approximation artifact but an integral part of the computational model, since spike timing is determined by threshold crossings rather than by exact numerical amplitudes.

All internal state variables (

) and parameters (

) are stored in this 6-bit format. In simulation, the IIR coefficients

and

(see Equation (

2)) are represented as floating-point values, but their effect is realized by exact power-of-two scaling. In hardware, these coefficients are implemented implicitly through bit shifts, without any explicit numerical multipliers or lookup tables. A small configuration register selects the appropriate shift amount for each coefficient.

This extreme reduction in numerical precision, relative to conventional 32-bit floating-point representations, yields substantial hardware benefits:

Reduced Silicon Area: Smaller registers and arithmetic units require significantly fewer logic resources.

Lower Power Consumption: Fewer switching bits and the elimination of multipliers reduce dynamic power dissipation.

Higher Operating Frequency: Shorter critical paths enable higher achievable clock rates.

The combination of temporal spike-based computation and low-precision arithmetic is central to the SPU’s efficiency. Spike timing preserves the expressive power needed for temporal processing, while coarse quantization enables compact, fast, and energy-efficient digital hardware.

2.6. Filter Order and Neural Dynamics Repertoire

The order of the IIR filter is a critical hyperparameter that determines the richness of the dynamical behaviors the SPU can exhibit. The choice of a second-order system represents a deliberate trade-off between computational complexity and functional capability, enabling the realization of a wide range of temporally selective neural behaviors.

First-Order (e.g., LIF equivalence): A first-order IIR filter can be configured to replicate the behavior of a Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron. It performs a simple exponential integration of input currents, characterized by a single time constant governing the decay of the membrane potential. While such a system is highly efficient, its behavioral repertoire is limited primarily to passive integration and lacks the ability to express resonance or oscillatory dynamics that are important for temporal pattern processing.

Second-Order (Proposed Model): The second-order transfer function in Equation (

2) is the minimal configuration capable of supporting resonant and damped oscillatory dynamics. The complex-conjugate pole pair enables the neuron to exhibit frequency selectivity, allowing it to respond preferentially to spike trains with specific temporal structure. This property is analogous to subthreshold resonance observed in biological neurons [

9] and provides a powerful mechanism for discriminating spatiotemporal input patterns. In this sense, the second-order SPU acts as a compact, tunable temporal filter rather than a simple integrator.

Higher-Order (Third and Fourth): Higher-order filters can produce even richer dynamics, including multiple resonant modes and sharper frequency selectivity. However, each increase in order introduces additional state variables and coefficients, significantly enlarging the parameter space and increasing both hardware cost and training complexity. In many practical settings, these gains in expressiveness do not justify the associated overhead.

The second-order SPU therefore represents a well-balanced operating point between dynamical richness and implementation efficiency. It provides substantially greater temporal expressiveness than first-order models, while avoiding the rapidly increasing complexity of higher-order systems. When more complex dynamics are required, they can be realized at the network level by composing multiple second-order SPUs, rather than by increasing the order of individual neurons.

The dynamical behavior of the SPU is determined jointly by its IIR coefficients (, ), which set the location of poles and zeros and hence the temporal filtering properties, and by the synaptic weights () and firing threshold (), which determine how incoming spikes interact with these dynamics. Together, these parameters allow a single second-order SPU to exhibit a wide range of behaviors relevant to temporal spike processing, including tonic firing, bursting, transient responses, and frequency-selective activation.

A further distinguishing feature of the SPU is that its filter coefficients are themselves trainable parameters. This extends the adaptive capacity of the neuron beyond synaptic weights and thresholds, allowing the temporal dynamics of the cell to be shaped by learning. In contrast, most traditional spiking neuron models rely primarily on synaptic plasticity, with their intrinsic dynamical form fixed a priori.

While biologically detailed models such as Hodgkin–Huxley and Izhikevich are invaluable for studying neural physiology, their reliance on high-precision arithmetic and nonlinear operations makes them poorly matched to the constraints of digital neuromorphic hardware. The SPU, by contrast, achieves a comparable diversity of temporal behaviors using a compact, linear, and hardware-efficient dynamical core.

3. Training and Temporal Coding

3.1. Simulation and Numerical Model

A cycle-accurate simulation of the SPU was implemented in Python to validate its functionality before hardware deployment. The simulation strictly adheres to the proposed numerical constraints: all operations—including the arithmetic shifts for coefficient multiplication—are performed using 6-bit two’s complement integer arithmetic. This ensures that the simulation accurately models the quantization and overflow behavior that will occur in the actual digital hardware, providing a faithful representation of the system’s performance.

This cycle-accurate approach ensures that all reported behaviors are directly transferable to real digital implementations.

3.2. Temporal Pattern Discrimination Task

To evaluate the computational capability of a single SPU, a temporal pattern discrimination task was designed. The neuron receives input from four synapses (

), each capable of emitting discrete spike events. Two deterministic spatio-temporal patterns, denoted as Pattern A and Pattern B, were defined and serve as the target classes. Each pattern consists of a specific arrangement of input spikes across the four synapses over a fixed time window, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

In addition to these two target patterns, the SPU is exposed to stochastic noise during training. Instead of a single fixed noise template, each fitness evaluation includes five independently generated random noise patterns drawn from a stochastic spike generator. These patterns contain uncorrelated spikes with random timing and synapse assignment, forming a distribution of distractors rather than a single adversarial example. This design forces the SPU to learn temporal selectivity that generalizes across a family of irrelevant inputs.

The desired behavior is that the SPU emits a single output spike at a pattern-specific time when presented with Pattern A or Pattern B, and remains silent for noise inputs. Temporal classification is therefore encoded in the time-to-first-spike of the output neuron, rather than in the number of spikes.

3.3. SPU Parameter Space

Each candidate SPU configuration is represented by a 10-dimensional parameter vector encoding the four synaptic weights (

–

), the firing threshold (

), and the coefficients of the second-order IIR membrane filter (

–

,

–

).

Figure 9 illustrates how these physical parameters are mapped into a unified search space shared by both the genetic algorithm (GA) and the particle swarm optimizer (PSO).

Although the PSO operates in a continuous 10-dimensional space, all candidate solutions must be projected onto the discrete, hardware-feasible domain before fitness evaluation. Specifically, all parameters are represented as signed 6-bit integers in the range , and the IIR coefficients are further constrained to a predefined set of power-of-two values. This discretization step ensures that every evaluated particle corresponds to a realizable SPU instance, preserving consistency between software optimization and digital hardware implementation.

The same parameterization is used by the GA, where each element of the vector is treated as a gene, and by the PSO, where the vector corresponds to a point in a continuous search space. This unified representation allows direct comparison between optimization strategies while enforcing strict hardware compatibility.

Beyond defining the feasible search domain, the IIR-based formulation of the SPU also enables the use of established system-theoretic knowledge to guide optimization. Because the stability, damping, and transient behavior of a second-order IIR filter can be inferred directly from its coefficients, the fitness function can incorporate penalties or preferences for specific dynamical regimes, such as overdamped, underdamped, or rapidly decaying responses. This allows the optimization process to favor stable or well-conditioned temporal filters, or alternatively to explore oscillatory or resonant dynamics when such behavior is beneficial for a given task. By relaxing the requirement of biological fidelity, the parameter space becomes amenable to principled, knowledge-guided exploration based on classical discrete-time dynamical systems theory.

3.4. Genetic Algorithm Baseline

A genetic algorithm (GA) was employed in the initial version of this work to demonstrate the feasibility of training the SPU under strict quantization and power-of-two constraints. Each individual in the population represents a candidate SPU parameter vector as defined in

Section 3.3, and its fitness is evaluated based on the ability to produce correctly timed output spikes for the two target patterns while suppressing activity for noise inputs.

The GA operates through tournament selection, uniform crossover, and adaptive point mutation, while enforcing that all parameters remain within the hardware-feasible domain. Elitism is used to preserve the best-performing solutions across generations. In the present revision, the GA serves as a reference method for exploring the same constrained parameter space later addressed using PSO.

Table 1.

Genetic algorithm hyperparameters used as baseline.

Table 1.

Genetic algorithm hyperparameters used as baseline.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Population size |

150 individuals |

| Max. generations |

1000 |

| Selection method |

Tournament (size 6) |

| Crossover |

Uniform, per gene |

| Mutation |

Adaptive point mutation |

| Elitism |

Top 5 individuals |

3.5. Particle Swarm Optimization

The particle swarm optimizer (PSO) was adopted in this revised work as an alternative population-based method for exploring the same 10-dimensional SPU parameter space defined in

Section 3.3. Each particle represents a candidate SPU configuration, and its position and velocity are updated based on both individual and global best solutions.

Robustness during training is enforced through stochastic noise injection. For each fitness evaluation, the SPU is stimulated with the two target spatio-temporal patterns and with five independently generated random noise patterns. This prevents overfitting to a fixed distractor and forces the optimizer to discover parameter sets that generalize across a distribution of irrelevant spiking activity.

The PSO hyperparameters used in this work are summarized in

Table 2. All particles evolve within the same quantized, power-of-two constrained parameter space as used by the genetic algorithm baseline, allowing both optimizers to be evaluated under identical hardware constraints.

Figure 10 shows representative convergence curves for multiple PSO runs. In all cases, the fitness increases rapidly during the first iterations and stabilizes within approximately 100–300 iterations, indicating consistent convergence behavior within the constrained SPU parameter space.

The PSO thus provides a set of optimized SPU parameter vectors that satisfy the temporal discrimination objective under stochastic noise. The resulting learned dynamics are analyzed in the following subsection.

3.6. Learned Temporal Responses

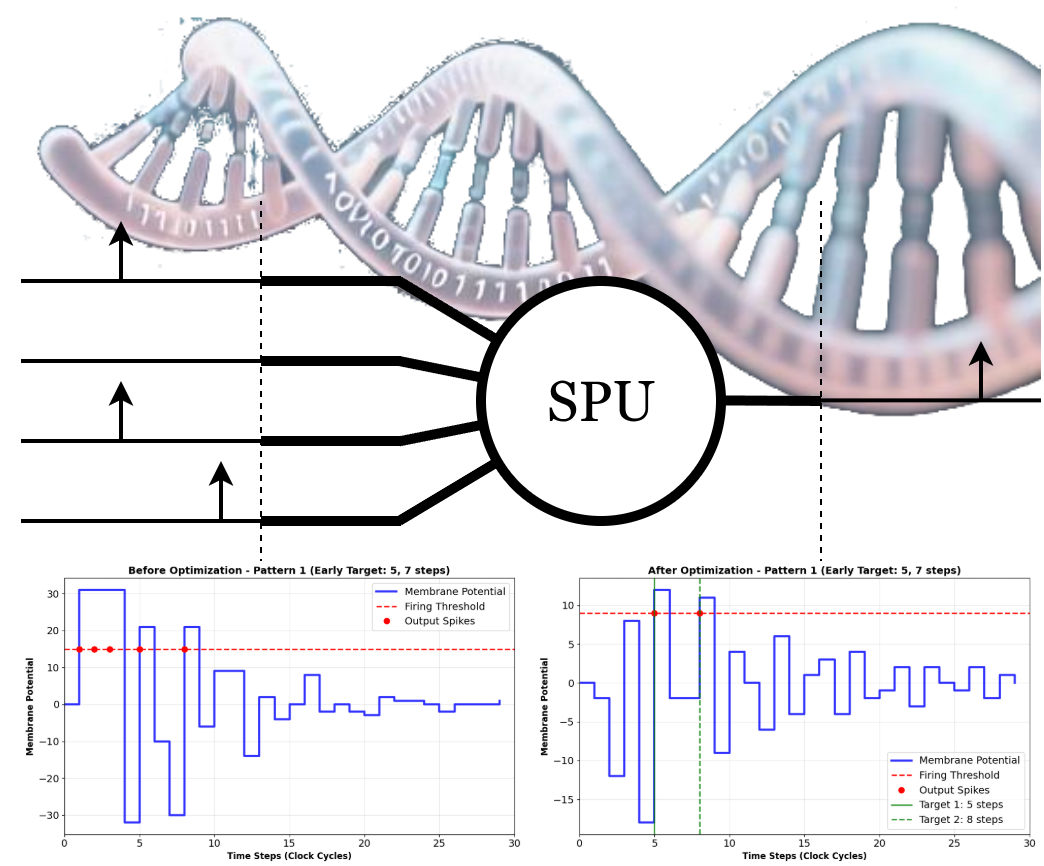

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the membrane dynamics of four SPU instances before and after PSO-based training. Although all trained neurons correctly discriminate the two spatio-temporal patterns, their internal dynamics differ substantially, indicating that the task admits multiple valid IIR configurations. This diversity reflects the structure of the underlying filter dynamics: different pole–zero placements can yield similar spike timing while exhibiting distinct transient responses.

Because the SPU dynamics are governed by a second-order IIR filter, the optimization process can be guided by well-established principles from digital signal processing. For example, changes in the feedback coefficients directly affect damping and resonance, enabling informed exploration of the parameter space. This stands in contrast to conventional spiking neuron models, whose nonlinear differential equations offer limited analytical insight. The IIR-based formulation therefore enables both efficient optimization and predictable dynamical behavior.

It is important to note that the large amplitude oscillations visible in some trained responses do not indicate numerical instability. All internal state variables are explicitly limited to the interval , and the observed waveforms reflect a limited and quantized IIR dynamic, rather than uncontrolled growth.

Moreover, such oscillations, in this case, are naturally limited below the threshold line, constituting subthreshold oscillations, a natural and often necessary behavior.

Since the noise patterns are randomly regenerated at each evaluation, the learned dynamics are not tuned to suppress a single fixed distractor but instead exhibit statistical robustness to unstructured spiking activity. As illustrated in

Figure 11, some trained configurations may still produce occasional noise-induced spikes, reflecting the inherent stochastic excitation of a low-order IIR system. By contrast, the solutions shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 achieve stronger noise suppression while preserving correct temporal discrimination. Together, these results indicate that the PSO discovers a family of valid temporal filters, representing different trade-offs between selectivity and sensitivity rather than a single brittle solution.

4. Hardware Implementation and Cost Analysis

4.1. SPU Synthesis Methodology

The SPU core used in this work implements four synaptic inputs and second-order IIR membrane dynamics, fully described in synthesizable VHDL. Two complementary synthesis flows were employed to evaluate its hardware cost. First, a technology-agnostic flow based on Yosys was used to estimate logic depth, LUT count, and an equivalent CMOS gate count across multiple FPGA families and standard-cell targets. Second, a vendor-specific flow based on Intel Quartus was used to synthesize the same RTL for a MAX10 device (10M50DAF484C7G), providing technology-specific resource utilization, clock frequency, and preliminary power estimates.

To ensure functional equivalence between the hardware description and the behavioral model used during training and analysis, the VHDL implementation was validated against the Python-based SPU simulator. Identical stimulus patterns were applied to both models, and their membrane trajectories and output spike times were compared using GHDL and GTKWave for the RTL and NumPy-based simulation for the reference model. This cross-validation step confirms that the synthesized hardware faithfully implements the IIR-based temporal dynamics and spike-generation logic used throughout this work.

Figure 15 shows the response of the SPU obtained from the Python reference model for two representative spatio-temporal input patterns, including the input spike raster, the quantized membrane potential trajectory, and the resulting output spikes. Both patterns are displayed on a single time axis for direct comparison.

The same two input patterns were then applied to the VHDL implementation and simulated using GHDL, with internal signals and the output spike observed in GTKWave, as shown in

Figure 16. The close correspondence between the Python traces and the RTL waveforms confirms that the synthesized hardware reproduces the same IIR-based temporal dynamics and spike-generation behavior used during training and analysis.

4.2. Multiplier-Based Neuron Implementations

The comparison in

Table 3 contrasts the proposed SPU with representative single-neuron hardware implementations that realize continuous-time or nonlinear membrane dynamics through arithmetic-intensive datapaths. These include a Hodgkin–Huxley neuron implemented on an FPGA using CORDIC-based arithmetic [

10], an asynchronous ASIC implementation of the Izhikevich model using full multipliers [

11], a high-speed LIF and Hodgkin–Huxley implementation based on look-up tables and counters [

12], and an FPGA realization of the Izhikevich neuron using multiplier-based arithmetic [

13].

Although these designs differ in neuron model and target technology, they share a common architectural characteristic: their membrane dynamics are derived from continuous-time differential equations or nonlinear update rules that require either multipliers, CORDIC engines, or large LUTs to approximate nonlinear functions. This results in datapaths dominated by arithmetic units and wide intermediate precision, which directly impacts area, power consumption, and maximum clock frequency, as reflected by the reported FPGA and ASIC implementations summarized in

Table 3.

In contrast, the proposed SPU implements its temporal dynamics as a discrete-time second-order IIR system operating entirely on 6-bit fixed-point state variables using shift-and-add arithmetic. Despite this radical reduction in arithmetic complexity, the SPU achieves clock frequencies comparable to or exceeding those of continuous-time neuron implementations, while occupying only a few hundred LUTs (≈ 1.5k CMOS gate equivalents, estimated from Yosys). This demonstrates that temporally selective spiking behavior does not require solving nonlinear differential equations in hardware, but can instead be realized through compact, low-precision, event-driven digital filters.

4.3. Multiplier-Free FPGA Implementations

This subsection compares the proposed SPU with FPGA-based neuron implementations that also avoid hardware multipliers and instead rely on look-up tables, adders, and shift-based arithmetic. The works considered include a LUT-based implementation of the Izhikevich neuron (Alkabaa et al.) and a base-2 shift–add approximation of the same model using the PWP2BIM approach (Islam et al.). These designs fall into the same arithmetic class as the SPU, making them the most relevant points of comparison.

Unlike the continuous-time and nonlinear models discussed in the previous subsection, these architectures explicitly target hardware efficiency by replacing general multipliers with precomputed LUTs or power-of-two shifts. However, as shown in

Table 4, most of these works do not report absolute hardware costs per neuron, providing only relative improvements or throughput-oriented metrics. The SPU, in contrast, reports complete post-synthesis figures for a single neuron on two FPGA platforms (MAX10 and Agilex-7), including logic utilization and clock frequency.

As a result,

Table 4 highlights a key difference between the SPU and existing multiplier-free designs: while prior works focus on accelerating specific neuron equations through approximations, the SPU introduces a native discrete-time neuron model whose dynamics are intrinsically compatible with shift–add arithmetic. This leads to a compact and fully disclosed hardware footprint, enabling transparent and scalable instantiation of large numbers of neurons on FPGA platforms.

4.4. SPU Across FPGA Families

To assess whether the proposed SPU architecture is tied to a specific FPGA family, the same SPU core was synthesized for a range of devices spanning low-end and high-performance platforms. This analysis isolates the intrinsic architectural cost of the SPU from technology-dependent effects such as routing and device-specific optimizations.

Table 5 reports post-synthesis logic utilization, logic depth, and estimated maximum clock frequency for MAX10, iCE40, Gowin, and Agilex–7 devices. These results demonstrate that the multiplier-free SPU maintains low logic complexity across all platforms while achieving substantially higher clock frequencies on modern FPGA families, indicating that its temporal processing capability scales with available hardware performance.

4.5. Summary and Implications

The hardware results presented in this section reveal a consistent trend across synthesis flows, FPGA families, and literature comparisons. Multiplier-based neuron models, including Izhikevich and Hodgkin–Huxley implementations, require either DSP blocks or floating-point units to support their continuous-time dynamics, which directly translates into increased area, reduced clock frequency, and higher power consumption. In contrast, the proposed SPU replaces these arithmetic-heavy datapaths with a compact shift-and-add IIR structure operating on 6-bit state variables.

This architectural choice is reflected in all three comparative views.

Table 3 shows that the SPU achieves clock frequencies comparable to or higher than multiplier-based neuron implementations while using orders-of-magnitude fewer arithmetic resources.

Table 4 further demonstrates that even among FPGA designs that explicitly avoid multipliers, the SPU remains highly compact and energy-efficient. Finally,

Table 5 shows that the same SPU core scales from low-end to high-performance FPGA families with consistently low logic utilization and increasing F

max.

Taken together, these results indicate that temporal spike discrimination does not require continuous-time differential equation solvers or high-precision arithmetic. Instead, event-driven IIR dynamics combined with coarse quantization are sufficient to support temporally selective spiking behavior, while enabling hardware implementations that are both fast and resource-efficient. This makes the SPU particularly well suited for large-scale neuromorphic systems where – ideally – millions of neurons must be instantiated under tight area and power constraints.

5. Interpretation and Implications

The results presented in

Section 3 and

Section 4 provide complementary views of the proposed Spike Processing Unit (SPU): the former demonstrates its ability to learn temporally selective spike responses, while the latter shows that this functionality can be realized in compact, high-speed digital hardware. This section interprets these results from a computational and architectural perspective.

5.1. Multiplicity of Valid Temporal Dynamics

A key observation emerging from

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 is that the temporal discrimination task admits multiple valid internal dynamics. Although all trained SPUs correctly emit a single spike at a pattern-dependent time, their membrane trajectories and transient responses differ substantially. This indicates that the optimization process does not converge to a unique “neuron”, but rather to a family of second-order IIR filters that implement the same input–output mapping.

From a signal-processing viewpoint, this is expected: different pole–zero configurations can produce similar impulse responses over a finite time window while exhibiting distinct damping, overshoot, or oscillatory behavior. The SPU therefore behaves not as a fixed biological model, but as a tunable temporal filter whose parameters can be adjusted to meet task-specific timing constraints.

5.2. Robustness Under Stochastic Input

The use of randomly generated noise patterns during training forces the optimizer to seek solutions that generalize across a distribution of distractors rather than a single fixed template. As a result, the learned SPU dynamics are statistically robust: correct spike timing for the target patterns is preserved even in the presence of unstructured spiking activity.

The results further show that robustness is not binary. Some configurations suppress noise more aggressively, while others permit occasional spurious spikes, as illustrated by the different solutions in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. These outcomes represent different trade-offs between sensitivity and selectivity that arise naturally from the low-order IIR dynamics, rather than from overfitting or training instability.

5.3. IIR-Based Neurons as Computational Primitives

The SPU departs fundamentally from conventional spiking neuron models based on nonlinear differential equations. By formulating membrane dynamics as a discrete-time IIR filter driven by spike events, temporal computation is expressed in terms of well-understood linear system properties. Stability, damping, resonance, and memory depth are directly controlled by the filter coefficients, providing an explicit link between parameter values and temporal behavior.

This formulation allows the learning problem to be interpreted as the shaping of a temporal filter rather than the fitting of a biophysical model. The availability of system-theoretic tools enables informed fitness design and principled exploration of the parameter space, while the low-order structure ensures that the resulting dynamics remain simple and predictable.

5.4. Implications for Neuromorphic Hardware

The hardware results in

Section 4 show that this temporal filtering paradigm maps naturally to digital logic. Because the SPU relies exclusively on shift-and-add arithmetic and low-precision state variables, its temporal discrimination capability is achieved without multipliers, floating-point units, or complex control logic. This allows large numbers of SPUs to be instantiated in parallel while maintaining high clock frequencies and low area per neuron.

Taken together, the learning and hardware results suggest a shift in how spiking computation can be implemented. Rather than emulating biological neurons at high numerical precision, temporally selective spiking behavior can be realized through compact IIR-based primitives that are both analytically tractable and hardware-efficient. This opens a path toward scalable neuromorphic systems in which temporal processing emerges from distributed, low-cost digital filters rather than from computationally expensive neuron models.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This work introduced the Spike Processing Unit (SPU), a spiking neuron model formulated as a discrete-time second-order IIR system operating on low-precision integer arithmetic. Rather than attempting to reproduce biological membrane dynamics in detail, the SPU is designed to implement temporally selective spiking behavior in a form that is analytically tractable and directly compatible with digital hardware.

The proposed formulation was validated through a temporal pattern discrimination task in which a single SPU was trained to emit pattern-dependent output spikes while remaining silent under stochastic noise. The results demonstrate that a compact, multiplier-free IIR structure is sufficient to support nontrivial temporal computation, and that multiple distinct internal dynamics can implement the same spiking behavior. This confirms that temporally selective spike generation can be viewed as a filtering problem in discrete time rather than as a numerical solution of nonlinear differential equations.

6.1. Summary of Contributions

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

An IIR-based spiking neuron: The SPU introduces a neuron model whose membrane dynamics are governed by a second-order IIR filter, enabling temporal spike computation using only shift-and-add arithmetic and low-precision state variables.

- 2.

A system-theoretic view of spiking computation: By formulating spike generation as a discrete-time filtering process, the SPU allows the use of classical concepts such as stability, damping, and transient response to analyze and guide neural dynamics.

- 3.

Hardware-faithful validation: Cycle-accurate Python models and synthesizable VHDL implementations were cross-validated, showing that the learned temporal dynamics transfer directly to digital hardware without numerical mismatch.

- 4.

A scalable hardware primitive: Synthesis results across multiple FPGA families and CMOS gate estimates indicate that the SPU provides a compact and high-speed building block for temporal processing in neuromorphic systems.

6.2. Future Work

The formulation of spiking neurons as discrete-time IIR systems opens several promising directions for future research. One important avenue is the systematic exploration of the constrained parameter space in terms of pole–zero placement and transient behavior. Hybrid optimization strategies combining evolutionary methods and particle swarm techniques may enable efficient identification of regions associated with specific temporal dynamics, such as rapid decay, oscillation, or sustained resonance.

At the learning level, biologically inspired mechanisms such as spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) can be adapted to update not only synaptic weights but also the filter coefficients themselves, allowing online or unsupervised adaptation of temporal dynamics.

From a systems perspective, networks of SPUs will be investigated for temporal classification and control tasks. Architectures such as liquid state machines, reservoir computing, and biologically inspired motifs (e.g., columnar or thalamocortical structures) provide natural testbeds for evaluating how IIR-based spiking units can support distributed temporal computation.

Finally, more detailed hardware studies, including post-layout power analysis and large-scale multi-neuron implementations, will further clarify the trade-offs between numerical precision, filter order, and computational performance in practical neuromorphic systems.

Figure 1.

Inter-spike interval (ISI) encoding. (a) Single-neuron ISI representation, where information is conveyed by the time interval between two spikes of the same neuron. (b) Population-based ISI representation, where different neurons encode distinct temporal intervals, enabling distributed temporal coding.

Figure 1.

Inter-spike interval (ISI) encoding. (a) Single-neuron ISI representation, where information is conveyed by the time interval between two spikes of the same neuron. (b) Population-based ISI representation, where different neurons encode distinct temporal intervals, enabling distributed temporal coding.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms for spike timing generation. (a) Analog-state-dependent models, where spike timing depends on the precise evolution of a continuous membrane potential. (b) Discrete-dynamics-driven models, where spike timing emerges from the evolution of a quantized IIR-like internal state.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms for spike timing generation. (a) Analog-state-dependent models, where spike timing depends on the precise evolution of a continuous membrane potential. (b) Discrete-dynamics-driven models, where spike timing emerges from the evolution of a quantized IIR-like internal state.

Figure 3.

Output actions enabled by spike timing. (a) Classification via first-spike (winner-takes-all) decoding. (b) Regression or control via ISI-to-PWM conversion.

Figure 3.

Output actions enabled by spike timing. (a) Classification via first-spike (winner-takes-all) decoding. (b) Regression or control via ISI-to-PWM conversion.

Figure 4.

Radar chart comparing representative neuron models across design criteria relevant to neuromorphic hardware. Axes include event-driven operation, temporal dynamics, biophysical fidelity, arithmetic simplicity, hardware implementability, and quantization robustness. The SPU emphasizes hardware efficiency and temporal dynamics over biological detail.

Figure 4.

Radar chart comparing representative neuron models across design criteria relevant to neuromorphic hardware. Axes include event-driven operation, temporal dynamics, biophysical fidelity, arithmetic simplicity, hardware implementability, and quantization robustness. The SPU emphasizes hardware efficiency and temporal dynamics over biological detail.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of the Spike Processing Unit (SPU). Input spikes are weighted and summed to form . This value is processed by a multiplier-less IIR filter (using shifts and adds) to compute the membrane potential . A comparator generates an output spike if exceeds the threshold . The selection unit allows two SPUs to be chained together, thereby increasing the effective order of the IIR filter to 4.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of the Spike Processing Unit (SPU). Input spikes are weighted and summed to form . This value is processed by a multiplier-less IIR filter (using shifts and adds) to compute the membrane potential . A comparator generates an output spike if exceeds the threshold . The selection unit allows two SPUs to be chained together, thereby increasing the effective order of the IIR filter to 4.

Figure 6.

Implementation of second-order IIR filter in direct form II to reduce the required register count.

Figure 6.

Implementation of second-order IIR filter in direct form II to reduce the required register count.

Figure 7.

Spike–timing control of SPU internal dynamics. Successive input spikes applied to a single synapse drive the IIR state through quiescent, oscillatory, and spiking regimes, illustrating that the effect of a spike depends on its arrival time and on the current dynamical state of the SPU.

Figure 7.

Spike–timing control of SPU internal dynamics. Successive input spikes applied to a single synapse drive the IIR state through quiescent, oscillatory, and spiking regimes, illustrating that the effect of a spike depends on its arrival time and on the current dynamical state of the SPU.

Figure 8.

Target spatio-temporal input patterns applied to the SPU. Pattern A (top) and Pattern B (middle) define the two classes to be discriminated, each specified by a fixed arrangement of spikes across the four synapses. The bottom row illustrates one realization of a random noise pattern drawn from the stochastic spike generator used during training. During optimization, five such noise patterns are generated independently for each fitness evaluation.

Figure 8.

Target spatio-temporal input patterns applied to the SPU. Pattern A (top) and Pattern B (middle) define the two classes to be discriminated, each specified by a fixed arrangement of spikes across the four synapses. The bottom row illustrates one realization of a random noise pattern drawn from the stochastic spike generator used during training. During optimization, five such noise patterns are generated independently for each fitness evaluation.

Figure 9.

SPU parameter space shared by genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO). The four synaptic weights (–), firing threshold (), and second-order IIR coefficients (–, –) form a 10-dimensional, hardware-constrained search space. In the GA, these parameters are encoded as individual genes, whereas in PSO they correspond to coordinates in a continuous 10D space.

Figure 9.

SPU parameter space shared by genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO). The four synaptic weights (–), firing threshold (), and second-order IIR coefficients (–, –) form a 10-dimensional, hardware-constrained search space. In the GA, these parameters are encoded as individual genes, whereas in PSO they correspond to coordinates in a continuous 10D space.

Figure 10.

Representative PSO convergence curves for different training runs (with different random seeds), showing consistent fitness improvement and convergence within a few hundred iterations.

Figure 10.

Representative PSO convergence curves for different training runs (with different random seeds), showing consistent fitness improvement and convergence within a few hundred iterations.

Figure 11.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 1. The vertical dashed lines indicate the desired firing targets for both patterns. The occasional spurious spikes observed after training reflect the intrinsic probabilistic dynamics of the IIR-based model under stochastic input, rather than a deficiency in the training process.

Figure 11.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 1. The vertical dashed lines indicate the desired firing targets for both patterns. The occasional spurious spikes observed after training reflect the intrinsic probabilistic dynamics of the IIR-based model under stochastic input, rather than a deficiency in the training process.

Figure 12.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 2, illustrating a different internal dynamics achieving the same classification task.

Figure 12.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 2, illustrating a different internal dynamics achieving the same classification task.

Figure 13.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 3, highlighting an alternative valid IIR configuration.

Figure 13.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 3, highlighting an alternative valid IIR configuration.

Figure 14.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 4, confirming robustness across multiple optimized dynamics.

Figure 14.

SPU membrane response before (left) and after (right) PSO training for solution 4, confirming robustness across multiple optimized dynamics.

Figure 15.

Python simulation of the SPU response to two spatio-temporal input patterns. Both patterns are shown in the same timeline for direct comparison. In the first pattern, synapses 0 and 1 receive an input spike at time step 1, while synapse 2 receives a spike at time step 3. In the second pattern, synapse 3 receives an input spike at time step 30, and synapses 2 and 0 receive spikes at time step 35. Panel (a) shows the input spike raster, panel (b) shows the quantized membrane potential of the SPU, and panel (c) shows the resulting output spikes, illustrating pattern-dependent spike timing.

Figure 15.

Python simulation of the SPU response to two spatio-temporal input patterns. Both patterns are shown in the same timeline for direct comparison. In the first pattern, synapses 0 and 1 receive an input spike at time step 1, while synapse 2 receives a spike at time step 3. In the second pattern, synapse 3 receives an input spike at time step 30, and synapses 2 and 0 receive spikes at time step 35. Panel (a) shows the input spike raster, panel (b) shows the quantized membrane potential of the SPU, and panel (c) shows the resulting output spikes, illustrating pattern-dependent spike timing.

Figure 16.

GTKWave waveforms from the VHDL implementation of the SPU for the same two spatio-temporal input patterns shown in

Figure 15. The signals

syn_in[3:0],

vmem_out[5:0], and

spike_out correspond to the synaptic inputs, quantized membrane potential, and output spike, respectively. The two patterns are time-shifted in the same way as in the Python simulation, allowing direct visual comparison between the behavioral and hardware implementations.

Figure 16.

GTKWave waveforms from the VHDL implementation of the SPU for the same two spatio-temporal input patterns shown in

Figure 15. The signals

syn_in[3:0],

vmem_out[5:0], and

spike_out correspond to the synaptic inputs, quantized membrane potential, and output spike, respectively. The two patterns are time-shifted in the same way as in the Python simulation, allowing direct visual comparison between the behavioral and hardware implementations.

Table 2.

Particle Swarm Optimization hyperparameters used for SPU training.

Table 2.

Particle Swarm Optimization hyperparameters used for SPU training.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Swarm size |

200 particles |

| Max. iterations |

300 |

| Cognitive coefficient

|

1.8 |

| Social coefficient

|

1.2 |

| Constriction factor

|

0.85 |

| Velocity update |

|

| Search space |

10-dimensional SPU parameter vector |

| Noise patterns per evaluation |

5 random trials |

| Allowed noise spikes |

0 |

| Settling window |

8 samples after last input |

| Fitness objective |

Correct timing for A and B, silence for noise |

Table 3.

Single-neuron hardware implementations based on arithmetic-intensive neuron models, compared with the proposed SPU. Area and maximum clock frequency () are reported when available.

Table 3.

Single-neuron hardware implementations based on arithmetic-intensive neuron models, compared with the proposed SPU. Area and maximum clock frequency () are reported when available.

| Metric |

Bonabi12 |

Imam13 |

Soleimani19 |

Alkabaa22 |

SPU |

| Model |

HH |

Izh |

LIF / HH |

Izh |

SPU |

| Platform |

Spartan-3 |

65 nm ASIC |

Stratix-III |

Virtex-II |

Agilex-7 |

| Tech |

CORDIC |

Mult |

LUT + ctr |

Mult |

Shift–add IIR |

| Area |

23k LUT + 99 DSP |

29.5k m2

|

N/A |

High |

373 LUT |

|

37.6M |

11.6M |

583M / 76M |

28M |

126.5M |

| Energy |

N/A |

0.5 nJ |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Table 4.

Single-neuron hardware implementations without multipliers, compared with the proposed SPU (Agilex-7 data from Yosys and Max10 from Quartus). Area and maximum clock frequency () are reported when available.

Table 4.

Single-neuron hardware implementations without multipliers, compared with the proposed SPU (Agilex-7 data from Yosys and Max10 from Quartus). Area and maximum clock frequency () are reported when available.

| Metric |

Alkabaa22 |

Islam23 |

SPU (Agilex-7) |

SPU (MAX10) |

| Model |

Izhikevich |

Izhikevich |

SPU |

SPU |

| Platform |

Virtex-II |

Zynq-7000 |

Agilex-7 |

MAX10 |

| Arithmetic |

LUT-based |

Base-2 shift–add |

Base-2 shift–add |

Base-2 shift–add |

| Area |

Not reported |

Not reported |

373 LUT |

304 LUT + 66 FF |

|

264 MHz |

Not reported |

126.5 MHz |

69.24 MHz |

| Notes |

Exact nonlin. |

Hybrid approx. |

Native discrete-time |

Native discrete-time |

Table 5.

Post-synthesis SPU implementation across FPGA families. Post-synthesis hardware metrics of the proposed SPU synthesized with Yosys for low- and high-end FPGA families. Logic utilization and estimated maximum clock frequency (Fmax) are reported for the same SPU design, showing that the multiplier-free architecture scales from resource-constrained devices (MAX10, iCE40) to high-performance platforms (Agilex-7).

Table 5.

Post-synthesis SPU implementation across FPGA families. Post-synthesis hardware metrics of the proposed SPU synthesized with Yosys for low- and high-end FPGA families. Logic utilization and estimated maximum clock frequency (Fmax) are reported for the same SPU design, showing that the multiplier-free architecture scales from resource-constrained devices (MAX10, iCE40) to high-performance platforms (Agilex-7).

| Platform |

Logic Cells (LUTs) |

Logic Depth |

Fmax* |

| Intel MAX10 |

401 |

93 |

63.2 MHz |

| Lattice iCE40 |

423 |

89 |

44.9 MHz |

| Gowin |

1670 |

109 |

41.7 MHz |

| Intel Agilex–7 |

373 |

79 |

126.5 MHz |