Introduction

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) represent the third generation of neural computing models, uniquely positioned at the intersection of biological plausibility and energy efficiency. Unlike conventional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), which process information in continuous-valued activations, SNNs operate using discrete temporal spikes, mimicking the behavior of biological neurons. This event-driven mechanism allows SNNs to perform sparse computation, resulting in significantly lower energy consumption—an advantage especially appealing for edge AI and neuromorphic systems [

1,

2].

As modern applications demand both high performance and low power, particularly in embedded and wearable systems, SNNs have garnered increasing attention. Neuromorphic chips such as IBM's TrueNorth [

3], Intel's Loihi [

4], and SpiNNaker [

5] exemplify dedicated hardware designed to exploit the asynchronous, sparse characteristics of SNNs. However, challenges remain in achieving competitive accuracy, robust training, and efficient hardware realization, especially when compared to well-optimized deep ANNs.

Recent advances have sought to bridge this gap from multiple directions. For example, PWM-based spike generators address timing inaccuracies in time-based SNNs [

6], while early termination of unsupervised STDP learning reduces latency and power during training [

7]. Meanwhile, hardware-efficient encoding strategies—such as single-spike phase coding—minimize conversion loss during ANN-to-SNN transformation [

8]. In parallel, event-based signal processing for neural spike detection is enabling ultra-low-power systems in applications such as implantable BMIs [

9], and radial-basis spiking neuron circuits using memristors offer new pathways for adversarial attack resilience [

10].

PWM-Based Spike Generation for Timing Precision

Time-based SNNs encode spike information via temporal intervals rather than voltage magnitude. While such encoding offers low-power benefits and higher neuron density, it is inherently sensitive to timing errors. Jo et al. [

6] addressed this by introducing a Pulse Width Modulation (PWM)-based spike generator, which substitutes timing-sensitive voltage threshold mechanisms with robust pulse-width-based logic. Their architecture demonstrated improved precision in spike generation and robustness to noise, especially when integrated into processing-in-memory (PIM) frameworks using memristive elements. This innovation provides a foundation for more reliable SNN deployment in timing-critical applications.

Other related works on time-based SNNs have explored using phase-locked loops, delay lines, and voltage-controlled oscillators, but PWM-based spike coding has shown greater resilience to clock skew and fabrication variations [

11,

12].

STDP Learning Acceleration via Early Termination

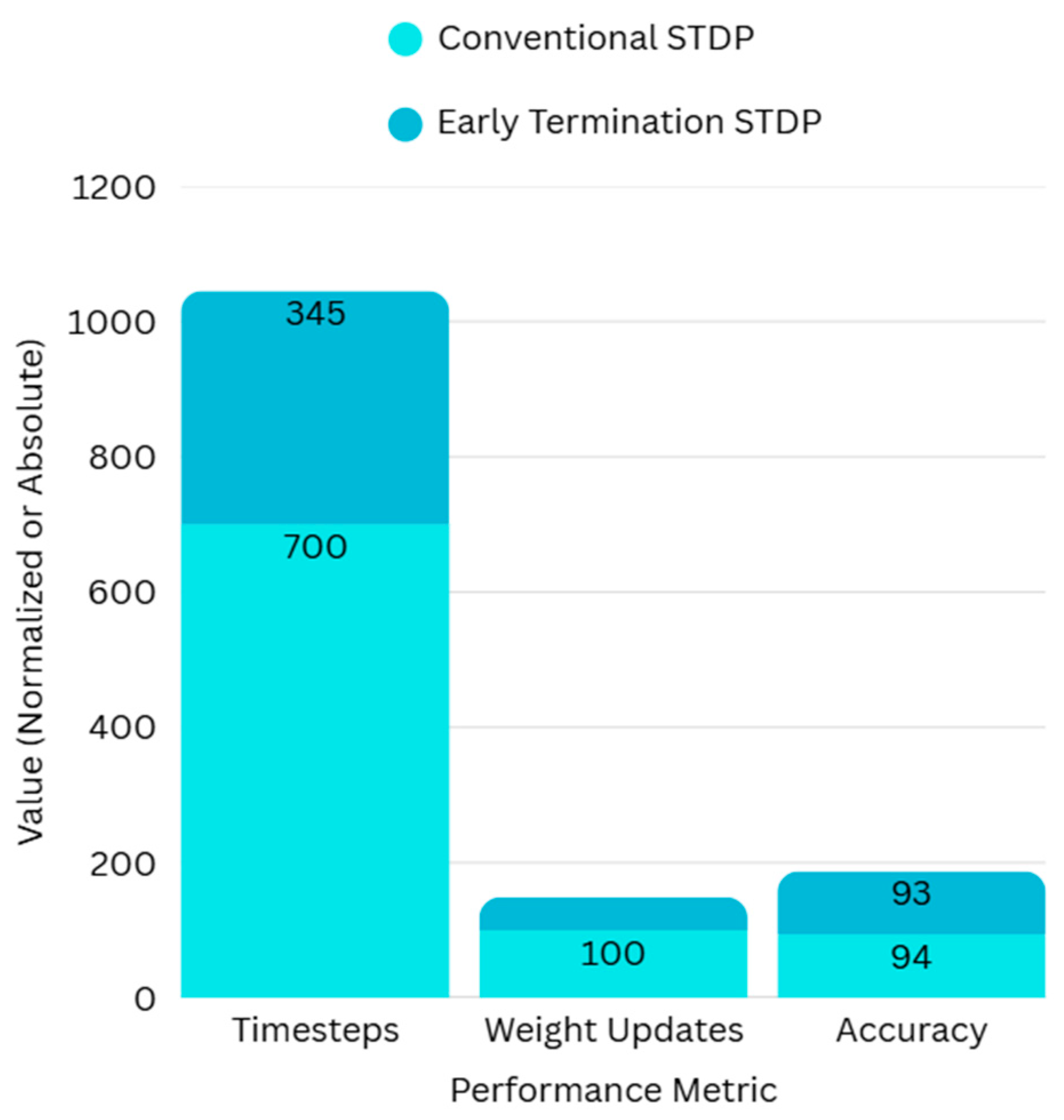

Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) is a biologically plausible, unsupervised learning rule used to adjust synaptic weights based on spike timing differences. However, its high latency and energy consumption pose a bottleneck for real-time applications. Choi and Park [

7] proposed a novel early termination strategy for STDP using output neuron spike counts. Their method reduced the training timesteps by 50.7% and weight updates by 51.1% on the MNIST dataset, with only a 0.35% drop in accuracy.

This approach aligns with broader trends to accelerate learning in neuromorphic systems, including homeostatic plasticity, lateral inhibition, and local threshold adaptation [

13,

14,

15]. These techniques enable more efficient learning and help preserve the energy advantage of SNNs.

Event-Based Spike Detection for Neuromorphic iBMIs

Event-driven processing is pivotal in applications like implantable Brain–Machine Interfaces (iBMIs), where power and data bandwidth are severely constrained. Hwang et al. [

9] proposed an SNN-based spike detector (SNN-SPD) that operates directly on delta- and pulse-count-modulated signals without signal reconstruction. Their system achieved 95.72% spike detection accuracy at high noise levels, while consuming only 0.41% of the computation of traditional ANN-based detectors.

This advancement fits within the growing body of neuromorphic compression and in-sensor computing research [

16,

17]. Event-based approaches align naturally with the spiking paradigm, eliminating redundant signal transmission and enhancing energy efficiency in embedded biomedical systems.

ANN-to-SNN Conversion Optimization via Phase Coding

To leverage mature training pipelines, many researchers convert pre-trained ANNs to SNNs. Yet, this conversion often suffers from precision loss, long inference time, and high spike rates. Hwang and Kung [

8] introduced the One-Spike SNN framework, employing phase coding with base manipulation to encode activation values using only a single spike per neuron. Their method maintained ANN-level accuracy with significantly fewer spikes and improved energy efficiency by up to 17.3×.

Phase coding schemes represent an evolution beyond traditional rate and temporal coding methods. Previous works have explored binary phase coding [

18], time-to-first-spike encoding [

19], and hybrid spike rate–phase fusion [

20], but single-spike phase approximation represents a new frontier in conversion efficiency.

Memristor-Based Neuron Circuits for Robustness

While conversion techniques and learning rules dominate the algorithmic side, advances in hardware-oriented SNN design are equally critical. Wu et al. [

10] designed a threshold-switching (TS) memristor-based radial basis spiking neuron (RBSN) circuit that emulates "near enhancement, far inhibition" (NEFI) properties seen in biological neurons. This configuration mitigates adversarial attacks, achieving ~80.6% classification accuracy on corrupted MNIST input (40% noise), compared to only ~49.2% for ReLU-based SNNs.

This work complements recent efforts in memristive neuromorphic hardware, including LIF neuron circuits, phase-change memory synapses, and RRAM-based processing-in-memory designs [

21,

22,

23]. By physically implementing non-linear spike responses, such circuits enhance robustness and bio-plausibility while maintaining low power profiles.

Comparative Analysis of Recent SNN Advancements

To provide a cross-sectional understanding of the innovations in recent SNN research, we present comparative insights across four primary metrics:

Accuracy

Energy/Computation Cost

Spike Efficiency

Hardware Suitability

Comparative Summary of Techniques

| Paper/ Technique |

Accuracy Impact |

Power/Computational Cost |

Spike Efficiency |

Hardware-Friendliness |

|

PWM-Based Spike Gen [6] |

Neutral (inference level) |

Reduced timing errors |

Maintains timing |

Memristor-compatible |

|

STDP Early Termination [7] |

Slight 0.35% drop |

~50% reduction |

Training optimized |

Digital & analog |

|

SNN-SPD iBMI [9] |

+2% over ANN-SPD |

0.41% compute of ANN-SPD |

Highly sparse |

Implant-grade (biomedical) |

|

One-Spike Coding [8] |

~0.5% loss (avg) |

4.6 – 17.3 times more energy saving |

Single spike per neuron |

ANN-to-SNN integration |

|

RBSN Memristor [10] |

30% increase in adversarial settings |

Low-power TS memristors |

Moderate (by design) |

Fabricated in SPICE |

The Table above summarizes five recent techniques in SNN research across four core evaluation metrics. Each row corresponds to one technique, with columns evaluating its impact on inference accuracy, energy or computational cost, spike efficiency (i.e., spike sparsity), and hardware suitability. This comparative matrix helps illustrate how each method contributes to the broader goal of efficient and robust neuromorphic computing.

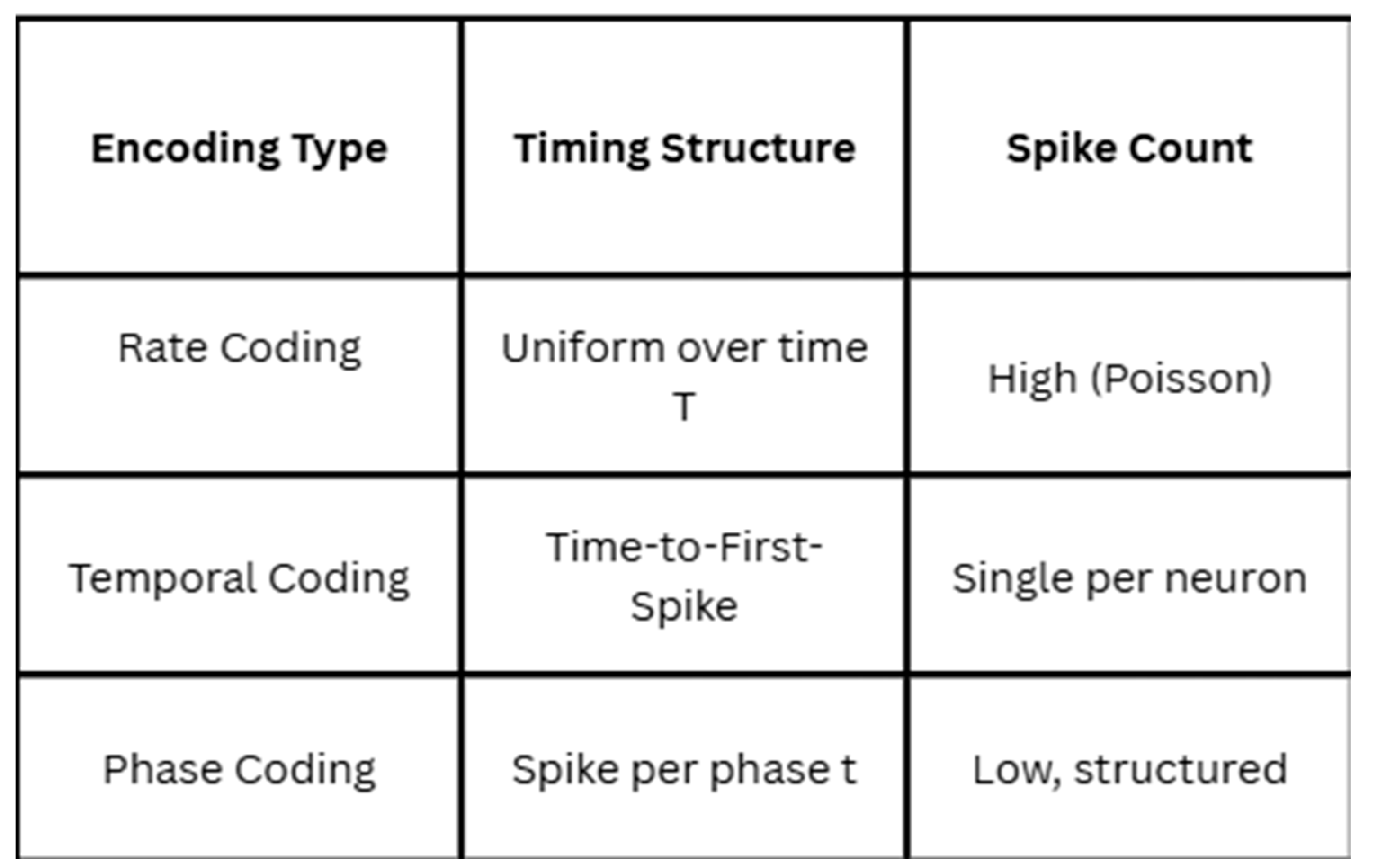

Spike Encoding Comparison

Figure 1 below illustrates the three primary spike encoding schemes employed in SNNs—rate coding, temporal coding, and phase coding—each differing in how spike information is temporally structured and represented. Rate coding distributes spikes uniformly over a time window, typically relying on Poisson-like spike trains, which leads to high spike counts and increased energy consumption. Temporal coding, in contrast, encodes information in the timing of the first spike, allowing each neuron to fire only once, thereby offering greater sparsity. Phase coding, a hybrid scheme, organizes spikes across discrete time phases with structured patterns, balancing encoding precision and spike efficiency. These encoding strategies serve as foundational mechanisms in ANN-to-SNN conversions and energy-efficient neuromorphic computation, with trade-offs between biological plausibility, latency, and hardware compatibility.

STDP Learning Efficiency with Early Termination

Figure 2 below shows the comparison between conventional STDP learning and spike count-based early termination. The early termination strategy reduces average training timesteps by 50.7% (from 700 to 345) and weight updates by 51.1% (from 100% to 48.9%), while maintaining a nearly identical MNIST classification accuracy (93.75% vs. 93.40%). This demonstrates the method’s potential to accelerate unsupervised learning in SNNs with minimal performance loss, making it ideal for low-latency neuromorphic systems.

Trade-Offs in SNN Design

While recent innovations in SNN research have improved accuracy, efficiency, and robustness, no single technique excels in all dimensions simultaneously. For instance, rate coding ensures accuracy but suffers from high spike counts and energy costs [

18], whereas temporal and phase coding reduce spike events but are harder to implement precisely in hardware [

8,

19]. Similarly, PWM-based SNNs improve spike timing reliability [

6], but are less widely adopted in large-scale networks due to limited design tooling.

Jiang et al. proposed an adaptive hybrid coding scheme that dynamically switches between rate and phase coding to address this issue [

24], while Kim and Yoon explored spike quantization to balance coding sparsity and network fidelity [

25].

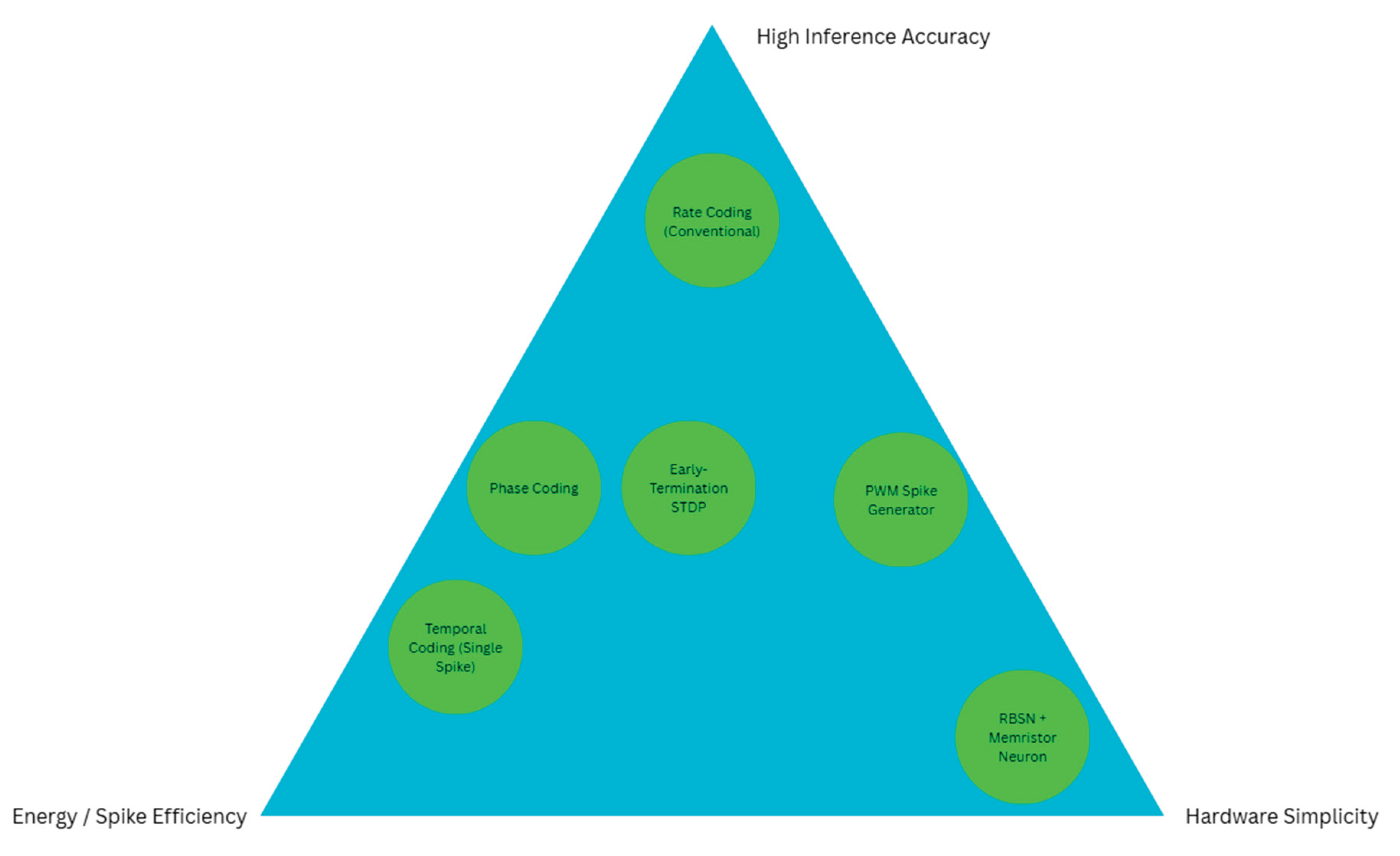

Figure 3 below summarizes the multi-objective trade-offs faced by SNN researchers, visualizing how each method balances accuracy, energy efficiency, and hardware complexity. Most recent methods optimize for two axes while sacrificing the third, revealing the need for unified co-optimization strategies. A visual summary of these multi-objective challenges is shown in

Figure 3, which maps SNN design methods into a trade-off triangle. At the top lies rate coding, offering strong accuracy but consuming high spike activity and requiring denser neuronal updates [

18]. Toward the energy-efficient corner, temporal coding and phase coding schemes reduce spike counts but often sacrifice robustness or require complex encoding circuits [

8,

19]. On the hardware side, solutions like the RBSN + memristor neuron [

5] enable simplified implementation but struggle to retain representational fidelity. Interestingly, hybrid designs such as the PWM spike generator [

6] and early-termination STDP [

2] occupy intermediate spaces—balancing energy and timing while maintaining moderate accuracy. This distribution illustrates a broader insight: optimizing all three objectives simultaneously remains elusive, motivating future research in unified co-design and adaptive spike control [

24].

Hardware Bottlenecks

Despite the promise of low-power neuromorphic computing, several hardware limitations persist. Memristor-based neurons, while compact and biologically plausible [

10], suffer from device variability, limited endurance, and non-linear switching behavior [

21,

22]. Chen et al. demonstrated that threshold drift in oxide-based memristors significantly affects spike reproducibility [

26]. Similarly, Shin et al. highlighted thermal instability as a barrier to scalability in 3D neuromorphic stacks [

27]. Additionally, most neuromorphic accelerators such as Loihi and TrueNorth are proprietary or partially open, limiting community-driven architectural testing [

3,

4]. Furthermore, Roy et al. [

28] emphasized that the lack of seamless interfacing between asynchronous SNN accelerators and synchronous edge processors is a critical bottleneck in real-time neuromorphic systems. In broader AI contexts, recent sustainable machine learning models designed for student attrition prediction [

46] have shown that resource-awareness and interpretability can be effectively combined—principles that resonate with neuromorphic objectives. Similarly, energy-adaptive robotic systems [

47] point toward the potential of neuromorphic architectures in future interactive and socially embedded technologies, especially in constrained human-in-the-loop environments.

Algorithmic Limitations

From the algorithmic side, supervised training of deep SNNs still lacks maturity compared to ANNs. Surrogate gradient methods are popular [

13,

14,

15], but they introduce gradient mismatch and are less biologically plausible. Lee et al. [

29] and Fang et al. [

30] recently introduced improved approximations of spiking derivatives to bridge this gradient gap. Nevertheless, scalability remains a challenge in deep SNN stacks. In terms of learning paradigms, most datasets used—such as MNIST, CIFAR, and Fashion-MNIST—are frame-based and do not reflect natural spatiotemporal event data. Gehrig et al. [

31] and Cramer et al. [

32] proposed new event-driven vision datasets (e.g., DVS128 Gesture, N-Caltech101) that better match the dynamic inference model of SNNs.

Future Opportunities

Several promising directions have emerged:

Algorithm-Hardware Co-design: Zhang et al. introduced a method for quantized ANN-to-SNN mapping with hardware-aware threshold adjustment [

33].

Self-Supervised Learning for SNNs: Mostafa et al. [

34] demonstrated contrastive learning strategies in spike-based networks, reducing reliance on labeled data.

Federated SNN Training: Tang et al. proposed asynchronous federated learning for neuromorphic edge nodes using STDP [

35].

SNN Transformers: Emerging research is beginning to combine spike-based attention modules with convolutional SNNs [

36].

These new directions suggest that by bridging algorithmic expressiveness with hardware viability, future SNNs may finally move from architectural novelty to practical deployment.

Figure 3.

Trade-off Triangle of Accuracy, Efficiency, and Hardware Simplicity in SNN Designs.

Figure 3.

Trade-off Triangle of Accuracy, Efficiency, and Hardware Simplicity in SNN Designs.

Figure 3 above shows a Trade-off triangle illustrating the performance balance across spiking neural network (SNN) design approaches. Each method is positioned according to its relative strength in three critical areas: inference accuracy (top), energy/spike efficiency (bottom-left), and hardware simplicity (bottom-right). No method dominates all three aspects, and most designs cluster toward optimizing only two, underscoring the inherent tension in building deployable SNN systems.

Conclusion

This review examined recent advancements in spiking neural networks (SNNs) through the lens of spike encoding strategies, learning mechanisms, and hardware realizations. From PWM-based spike generators to early-termination STDP and memristor-based spiking neurons, we highlighted innovations that push SNNs closer to practical, energy-efficient, and high-performance deployment. The trade-off triangle proposed in

Figure 3 provides a conceptual lens through which researchers can evaluate emerging SNN techniques across accuracy, energy efficiency, and hardware simplicity.

Despite this progress, SNNs still face critical challenges. These include limited generalization in deep architectures, difficulty in training with real-world dynamic datasets, and the absence of unified frameworks for algorithm-hardware co-design. Moreover, most SNN accelerators remain constrained to lab-scale datasets and small network depths, calling for more scalable system integration [

44]. Future work should focus on expanding benchmark datasets for event-driven tasks [

31], improving hardware-aware training pipelines [

33], and leveraging self-supervised and online learning to reduce labeling dependence [

34,

45]. As embedded learning systems advance [

48], their synergy with SNN accelerators becomes increasingly feasible, particularly for on-device anomaly detection and low-latency edge responses. Bridging these gaps will be essential to elevate SNNs from neuromorphic novelty to real-world deployment across robotics, edge AI, and biomedical signal processing.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- W. Maass. Networks of spiking neurons: The third generation of neural network models. Neural Networks 1997, 10, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. B. Furber et al. . The SpiNNaker Project. Proceedings of the IEEE 2014, 102, 652–665. [Google Scholar]

- P. A. Merolla et al. . A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 2014, 345, 668–673. [Google Scholar]

- M. Davies et al.. Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. IEEE Micro 2018, 38, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. B. Furber and F. Galluppi. A New Approach to Computational Neuroscience: Modeling the Brain on a Chip. IEEE Pulse 2012, 3, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- J. Jo, K. J. Jo, K. Sim, S. Sim, and J. Jun. A Pulse Width Modulation-Based Spike Generator to Eliminate Timing Errors in Spiking Neural Networks. in *Proc. Int. Conf. on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC) 2025, 1–4.

- CL Kok, CK Ho, L Chen, YY Koh, B Tian. A novel predictive modeling for student attrition utilizing machine learning and sustainable big data analytics. Applied Sciences.

- S. Hwang and J. Kung. One-Spike SNN: Single-Spike Phase Coding With Base Manipulation for ANN-to-SNN Conversion Loss Minimization. IEEE Trans. Emerging Topics in Computing 2025, 13, 162–175. [Google Scholar]

- C. Hwang et al.. Event-based Neural Spike Detection Using Spiking Neural Networks for Neuromorphic iBMI Systems. in *Proc. IEEE ISCAS.

- Z. Wu et al.. Threshold Switching Memristor-Based Radial-Based Spiking Neuron Circuit for Conversion-Based Spiking Neural Networks Adversarial Attack Improvement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II, Exp. Briefs 2024, 71, 1446–1449. [Google Scholar]

- C. Deng and S. Yu. Time-based spiking neuron circuits for neuromorphic computing: A review. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 2020, 67, 2521–2534. [Google Scholar]

- M. Sharifzadeh, A. A. Ahmadi, and A. Payandeh. A phase-encoded neuromorphic architecture using VCO-based neurons. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 2022, 69, 5001–5013. [Google Scholar]

- KHH Aung, CL Kok, YY Koh, TH Teo. An embedded machine learning fault detection system for electric fan drive. Electronics.

- Tavanaei, M. Ghodrati, S. R. Kheradpisheh, T. Masquelier, and A. Maida. Deep learning in spiking neural networks. Neural Networks 2019, 111, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- J. Kheradpisheh and T. Masquelier. Temporal backpropagation for training deep spiking neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- F. Akbarzadeh, J. Hashemi, and A. Rahimi. Neural data compression for implantable brain–machine interfaces using event-driven techniques. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 290–303. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Song, R. Chen, and Y. He. Neuromorphic signal processing with sparse event-based data. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 12534–12547. [Google Scholar]

- H. Kim, Y. H. Kim, Y. Kim, and S. Yoon. Efficient ANN-to-SNN conversion with burst coding and hybrid neuron model. in *Proc. IEEE CVPR, 7439. [Google Scholar]

- R. Rueckauer et al.. Conversion of continuous-valued deep networks to efficient event-driven networks for image classification. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 682. [Google Scholar]

- M. Mozafari et al.. Bio-inspired digit recognition using reward-modulated spike-timing-dependent plasticity in deep convolutional networks. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 94, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Boybat et al.. Neuromorphic computing with multi-memristive synapses. Nature Commun. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- T. Chang, S. H. Jo, and W. Lu. Short-term memory to long-term memory transition in a nanoscale memristor. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7669–7676. [Google Scholar]

- X. Liu et al.. A memristor-based neuromorphic computing system: From device to algorithm. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst. 2019, 9, 276–292. [Google Scholar]

- W. Jiang, Y. W. Jiang, Y. Yang, and K. Roy. Adaptive hybrid spike encoding for dynamic input sparsity in SNNs. in *Proc. IEEE CVPR, 3201. [Google Scholar]

- H. Kim and S. Yoon. Spike quantization for efficient ANN-to-SNN conversion. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar]

- J. Chen et al.. Understanding threshold drift in oxide memristors for SNN applications. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2024, 45, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, C.L.; Siek, L. Designing a Twin Frequency Control DC-DC Buck Converter Using Accurate Load Current Sensing Technique. Electronics 2024, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Roy, A. Sengupta, and A. Panda. Going beyond von Neumann with neuromorphic edge computing. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 1343–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Park, and T. Yu. Gradient-friendly training of deep SNNs via smooth spike response models. in *Proc. NeurIPS, 4553. [Google Scholar]

- W. Fang et al.. Deep residual learning in spiking neural networks. in *Proc. AAAI 2023, 37, 2671–2679. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . DVS128 Gesture dataset: A benchmark for dynamic vision. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 371–384. [Google Scholar]

- B. Cramer, T. Kaiser, and S. Wörgötter. Event-driven object recognition using spike encoding from N-Caltech101. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 15821–15830. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Zhang et al.. Hardware-aware quantized ANN-to-SNN conversion with dynamic thresholds. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2024, 43, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- H. Mostafa and S. Rumelhart. Self-supervised learning in SNNs with spike contrastive coding. in *Proc. ICLR.

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Teo, T.H.; Kato, K.; Koh, Y.Y. A Novel Implementation of a Social Robot for Sustainable Human Engagement in Homecare Services for Ageing Populations. Sensors 2024, 24, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee and, D. Sengupta. Towards neuromorphic transformers: Event-driven attention modules. in *Proc. ICASSP 2024, 3285–3289.

- P. U. Diehl et al. . Comparison of rate coding and temporal coding for SNNs. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2022, 29, 451–463. [Google Scholar]

- R. Brette et al.. Simulation of networks of spiking neurons: A review of tools and strategies. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- W. Wu et al.. Advances in learning algorithms for spiking neural networks: A review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 1879–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Deng and Y. Liang. Surrogate gradient learning in SNNs: State-of-the-art and challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45829–45841. [Google Scholar]

- J. Ni, Y. Wang, and K. Roy. Recent trends in hardware acceleration for SNNs. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- H. Li et al.. Memristor-enabled neuromorphic circuits for real-time SNNs: A review. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst. 2023, 13, 250–263. [Google Scholar]

- S. Choi and J. Park. Early Termination of STDP Learning with Spike Counts in Spiking Neural Networks. in *Proc. ISOCC.

- P. U. Diehl and M. Cook. Unsupervised learning of digit recognition using spike-timing-dependent plasticity. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Patel and, J. Smith. Self-supervised spiking networks for continual learning. in *Proc. IEEE IJCNN 2023, 1105–1112.

- Shin, Y. Li, and A. Seabaugh. Thermal impact in stacked neuromorphic chips. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 2023, 9, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- T. Tang, X. T. Tang, X. Luo, and F. Xue. Asynchronous federated STDP for spiking edge devices. in *Proc. IEEE IoT C.

- H. H. Aung, C. L. Kok, Y. Y. Koh, and T. H. Teo. An embedded machine learning fault detection system for electric fan drive. Electronics 2024, 13, 493. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).