Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

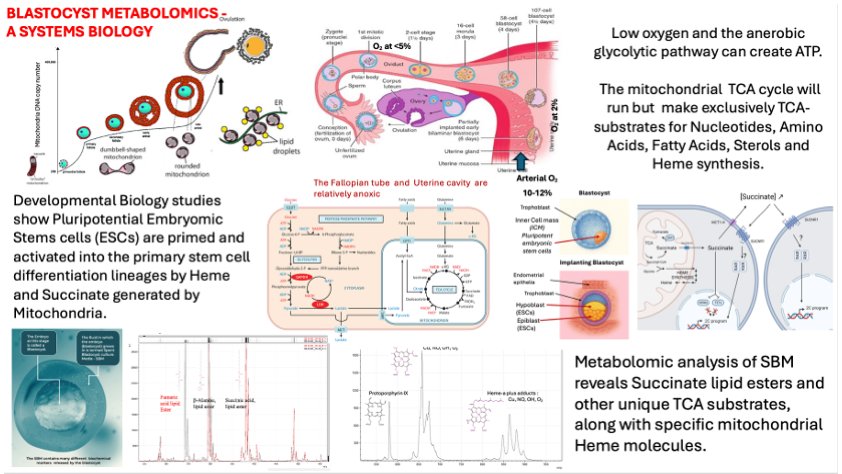

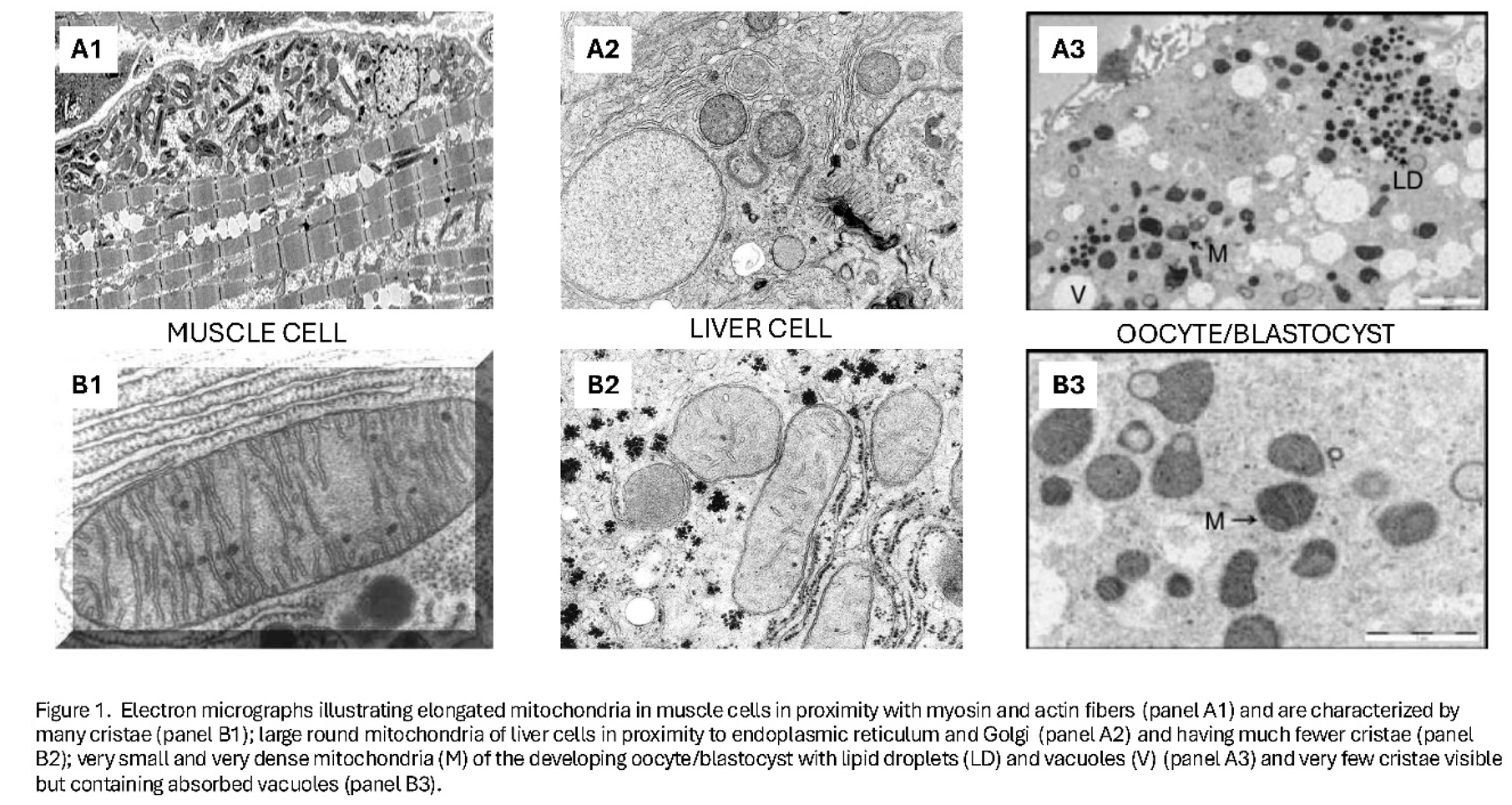

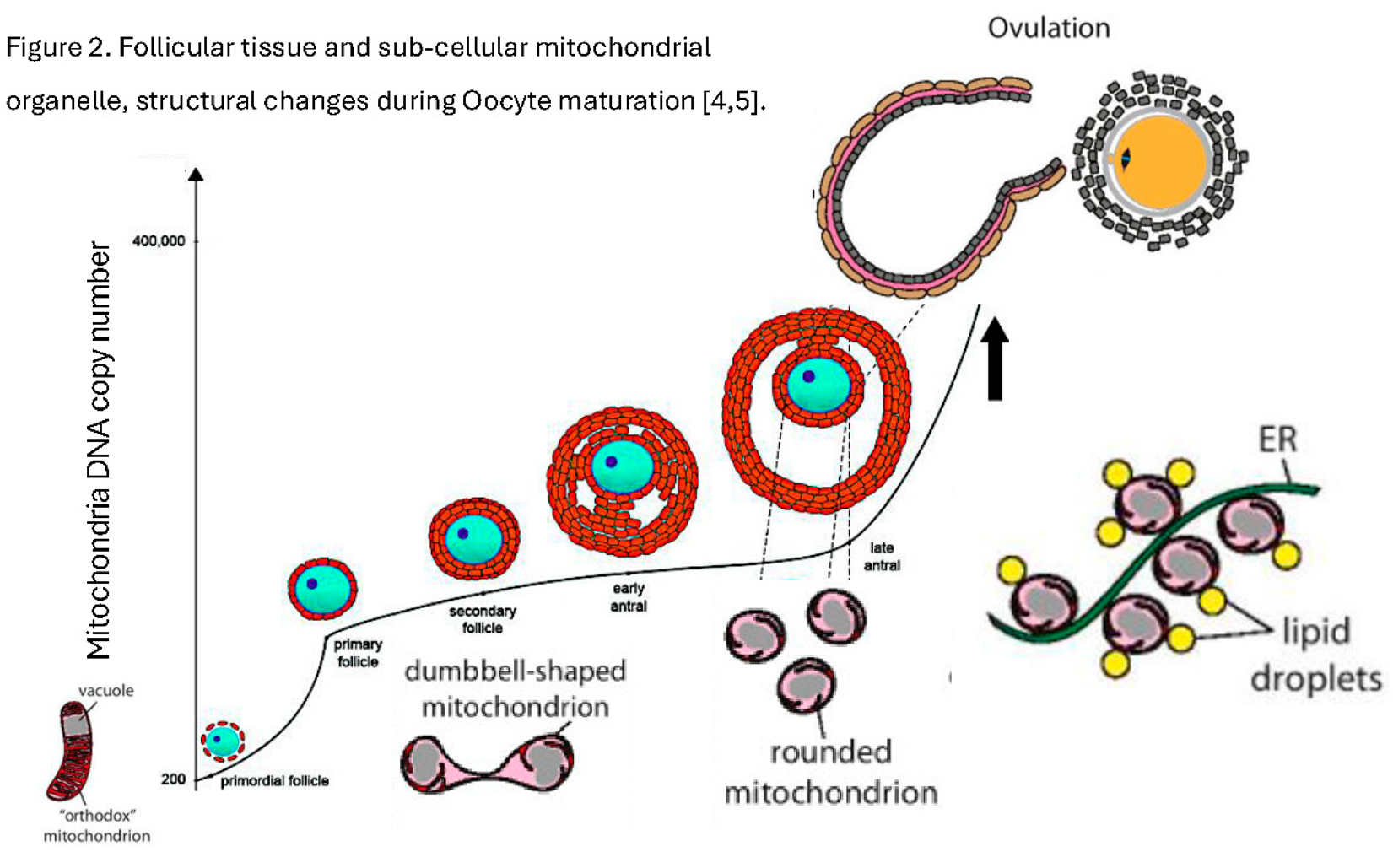

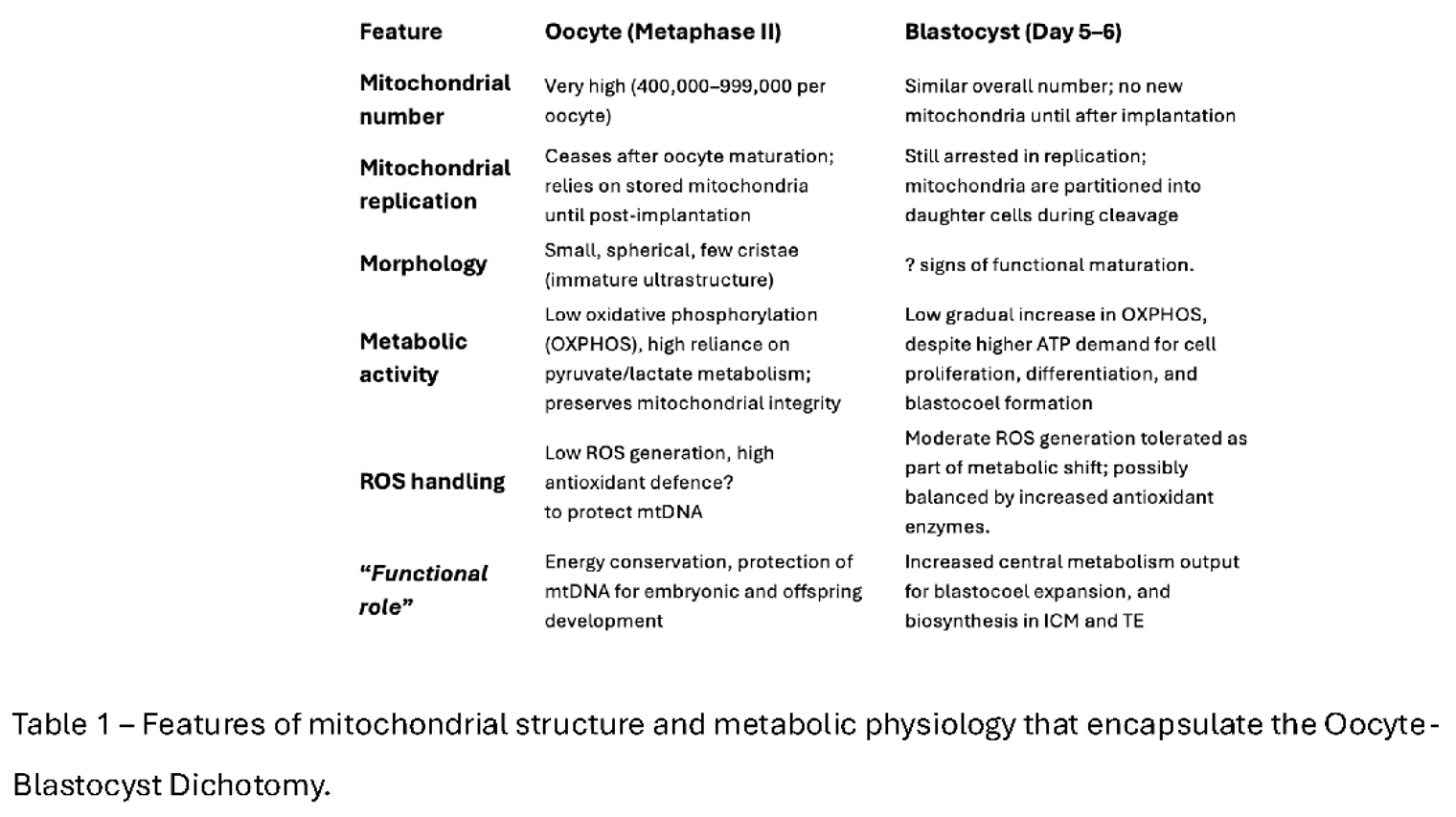

Introduction

- A)

- B)

- C)

Why Revisit the Oocyte–Blastocyst Mitochondrial Dichotomy?

Conclusions

References

- S.A. Nottola, G. Macchiarelli, G. Coticchio, S. Bianchi, S. Cecconi, L. De Santis, G. Scaravelli, C. Flamigni, A. Borini, Ultrastructure of human mature oocytes after slow cooling cryopreservation using different sucrose concentrations, Human Reproduction, 2007, 22:(4):1123–1133. [CrossRef]

- R. Dumollard, J. Carroll, M.R. Duchen, K. Campbell, K. Swann, Mitochondrial function and redox state in mammalian embryos, Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2009 20(3):346-353. [CrossRef]

- Van Hoeck, V., Leroy, J. L. M. R., Arias Alvarez, M., Rizos, D., Gutierrez-Adan, A., Schnorbusch, K., Bols, P. E. J., Leese, H. J., & Sturmey, R. G. (2013). Oocyte developmental failure in response to elevated nonesterified fatty acid concentrations: mechanistic insights. REPRODUCTION, 2013, 145(1): 33-44. [CrossRef]

- Chiaratti MR. Uncovering the important role of mitochondrial dynamics in oogenesis: impact on fertility and metabolic disorder transmission. Biophysical Reviews. 2021;13(6):967-981. [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, A.; Smitz, J.E.J.; Sukhikh, G.T.; Mazunin, I. The Role of Mitochondria in Oocyte Maturation. Cells 2021, 10, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, D.C.; Khrapko, K.; Tilly, J.L. Influence of Maternal Aging on Mitochondrial Heterogeneity, Inheritance, and Function in Oocytes and Preimplantation Embryos. Genes 2018, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang D, Keilty D, Zhang ZF, Chian RC. Mitochondria in oocyte aging: current understanding. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017, 9(1):29-38.

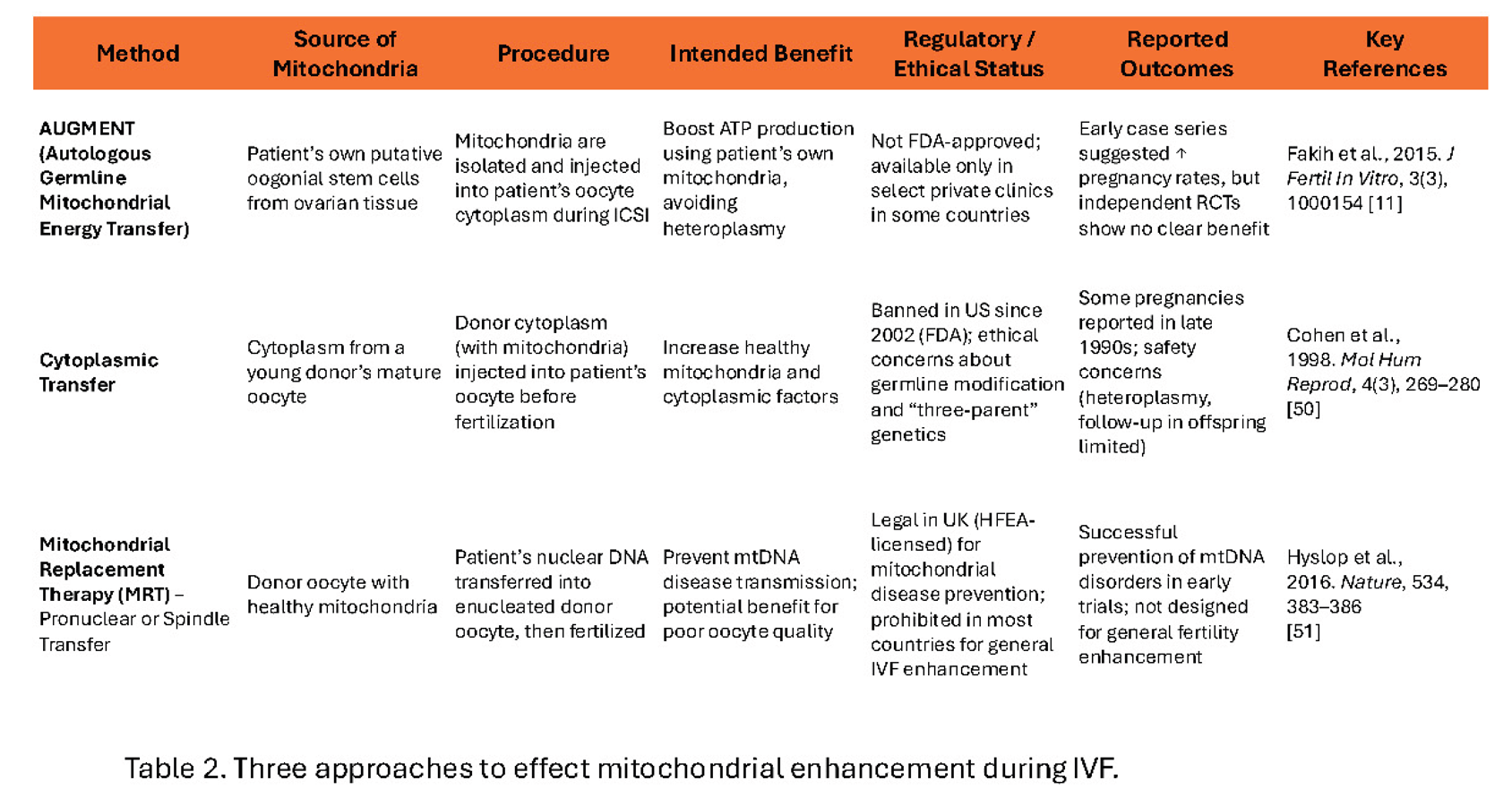

- Couzin-Frankel, J. Eggs' power plants energize new IVF debate. Firm adding energy-generating mitochondria to egg cells has already produced human pregnancies. SCIENCE, 2015, 348(6230): 14-15. [CrossRef]

- White YA, Woods DC, Takai Y, Ishihara O, Seki H, Tilly JL. Oocyte formation by mitotically active germ cells purified from ovaries of reproductive-age women. Nat Med. 2012,18(3):413-21. [CrossRef]

- Dale B, Wilding M, Botta G, et al. Pregnancy after cytoplasmic transfer in a couple suffering from idiopathic infertility: case report. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(7):1469–1472. [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M. H., El Shmoury, M., Szeptycki, J., Cruz, D., Lux, C.R., Verjee, S., Burgess, C.M., Cohn., G.M., Casper R.F. The AUGMENT treatment: Physician reported outcomes of the initial global patient experience. JFIV Reprod Med Genet 2015, 3:3. [CrossRef]

- Lee K. An Ethical and Legal Analysis of Ovascience – A Publicly Traded Fertility Company and its Lead Product AUGMENT. American Journal of Law & Medicine. 2018, 44(4):508-528. [CrossRef]

- https://www.technologyreview.com/2016/12/29/106805/turmoil-at-troubled-fertility-company-ovascience/.

- Dzeja, P.; Terzic, A. Adenylate Kinase and AMP Signalling Networks: Metabolic Monitoring, Signal Communication and Body Energy Sensing. 2009, 10, 1729–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.L., Cox, M.M. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 7th Edition, W.H. Freeman, New York, 2017. ISBN 10: 1319108245.

- Ng KYB, Mingels R, Morgan H, Macklon N, Cheong Y. In vivo oxygen, temperature and pH dynamics in the female reproductive tract and their importance in human conception: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2018, 24(1):15-34. [CrossRef]

- Brouillet, S., Baron, C., Barry, F. et al. Biphasic (5–2%) oxygen concentration strategy significantly improves the usable blastocyst and cumulative live birth rates in in vitro fertilization. Sci Rep 2021, 11:22461. [CrossRef]

- Au, H.-K., Yeh, T.-S., Kao, S.-H., Tzeng, C.-R., Hsieh, R.-H. Abnormal Mitochondrial Structure in Human Unfertilized Oocytes and Arrested Embryos. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2005, 1042: 177-185. [CrossRef]

- Motta, P.M., Nottola, S.A., Makabe, S., Heyn, R. Mitochondrial morphology in human fetal and adult female germ cells, Human Reproduction, 2000, 15:129–147. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nuevo, A., Torres-Sanchez, A., Duran, J.M. et al. Oocytes maintain ROS-free mitochondrial metabolism by suppressing complex I. Nature 2022, 607:756–761. [CrossRef]

- Surmacki, J.M., Abramczyk, H., Sobkiewicz, B., Walczak-Jędrzejowska, R., Słowikowska-Hilczer, J., Marchlewska, K. The role of cytochrome c in mitochondrial metabolism of human oocytes. bioRxiv 2024.10.01.616010. [CrossRef]

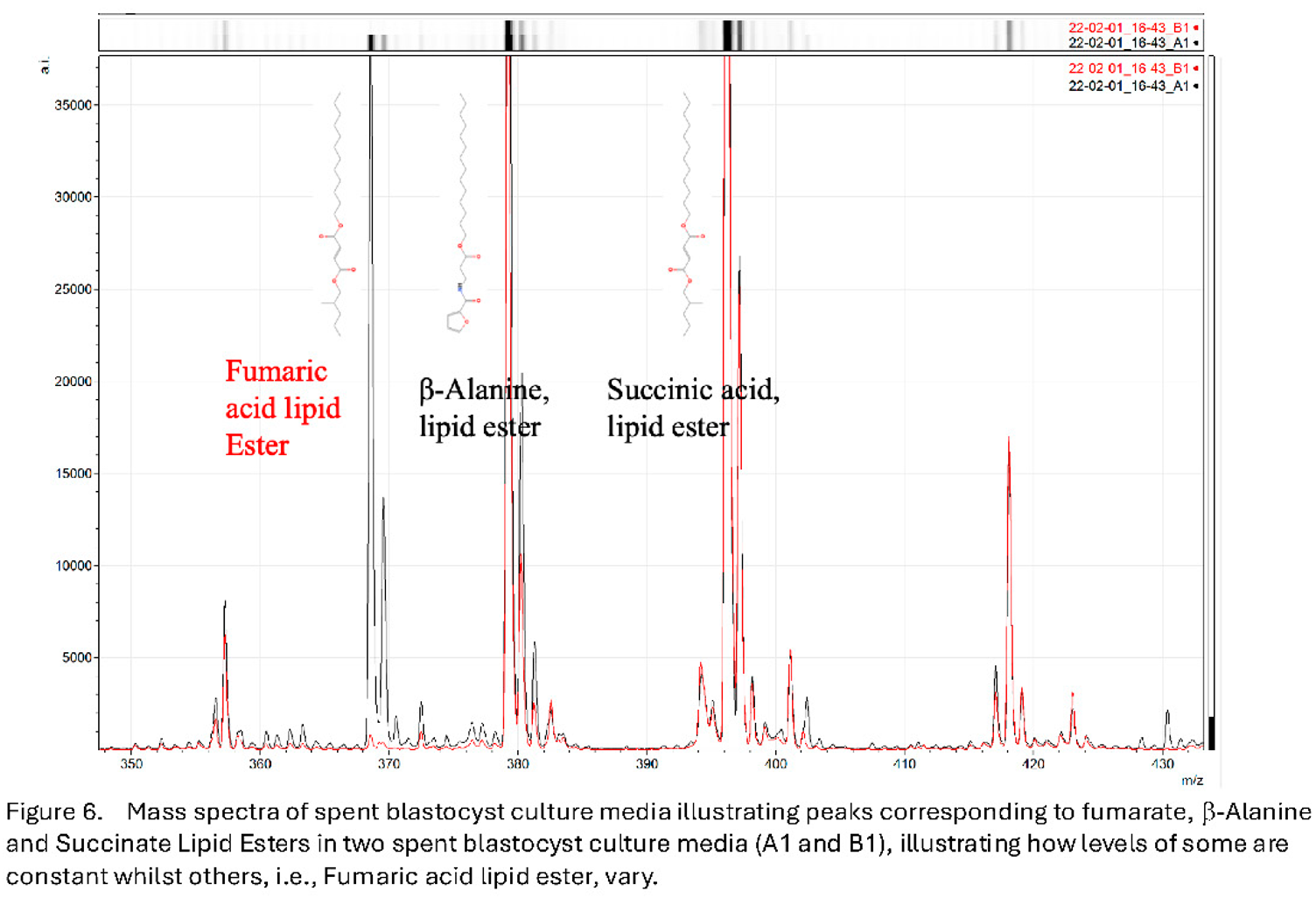

- Baştu, E.; Parlatan, U.; Başar, G.; Yumru, H.; Bavili, N.; Sağ, F.; Bulgurcuoğlu, S.; Buyru, F. Spectroscopic analysis of embryo culture media for predicting reproductive potential in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 14(3):145-150. [CrossRef]

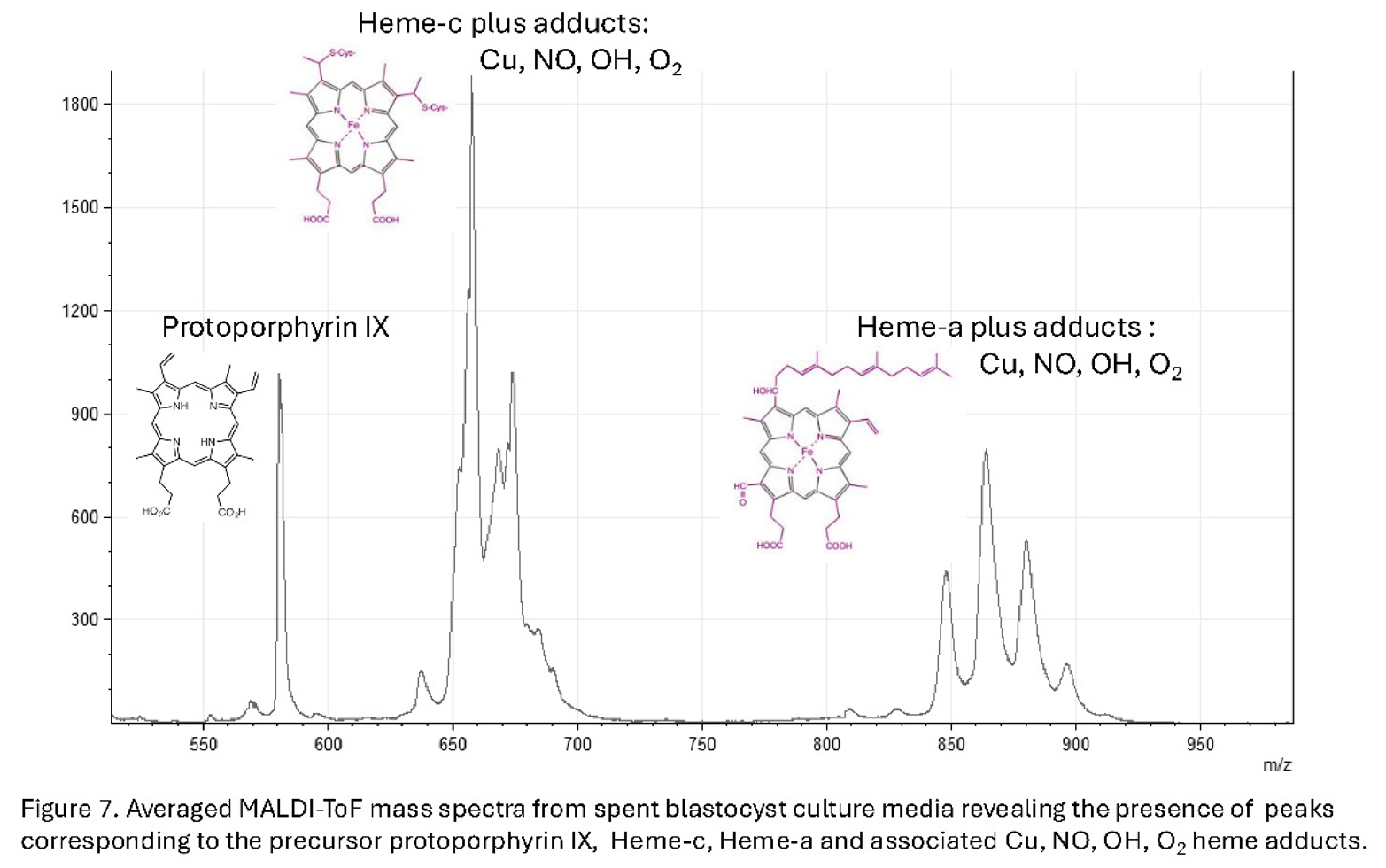

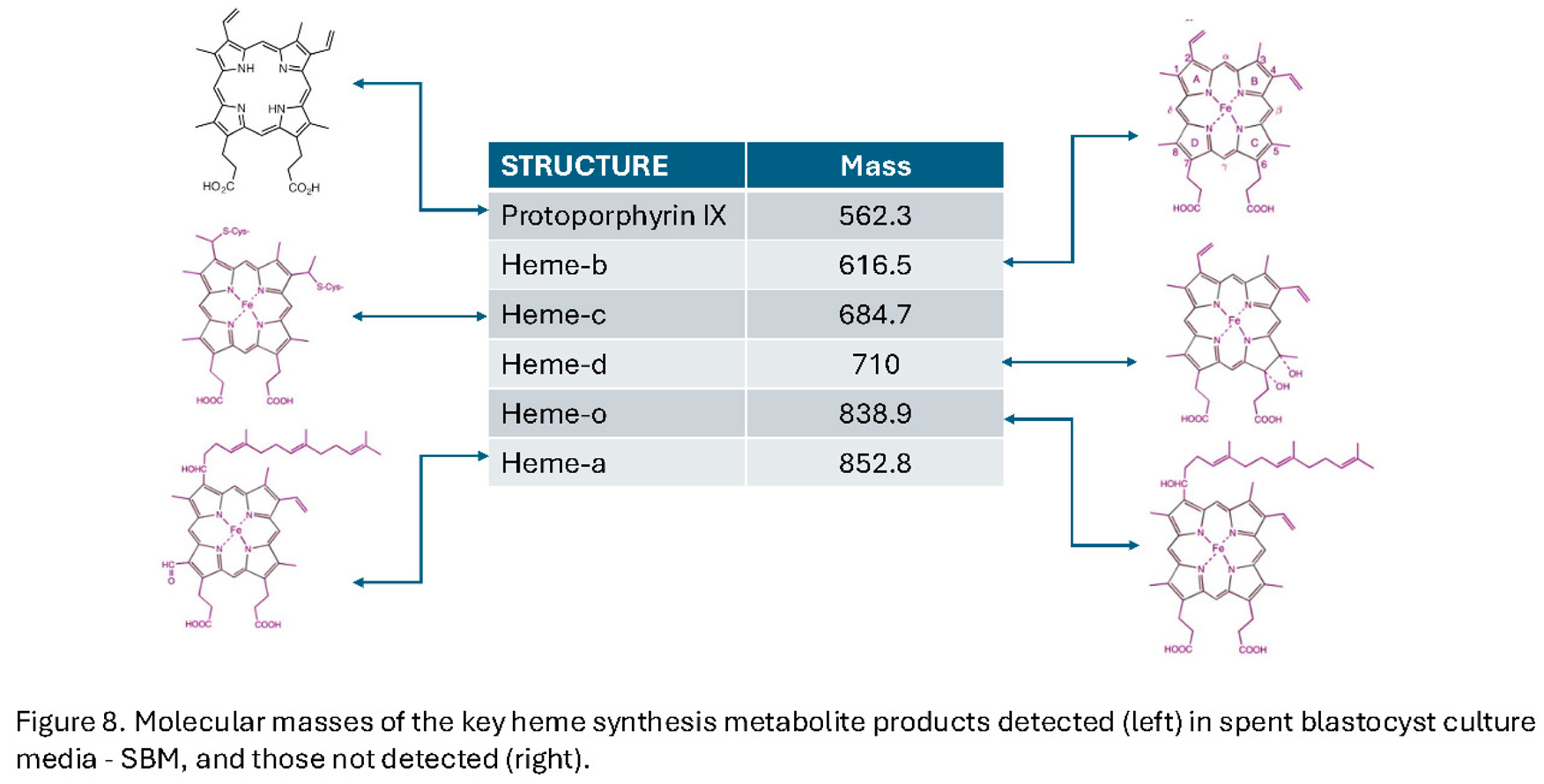

- Iles, R.K.; Sharara, F.I.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Abdo, G.; Keshavarz, S.; Butler, S.A. Secretome profile selection of optimal IVF embryos by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019, 36(6):1153-1160.

- Nagy, Z.P.; Sakkas, D.; Behr, B. Symposium: innovative techniques in human embryo viability assessment. Non-invasive assessment of embryo viability by metabolomic profiling of culture media ('metabolomics'). Reprod Biomed Online. 2008, 17(4):502-507. [CrossRef]

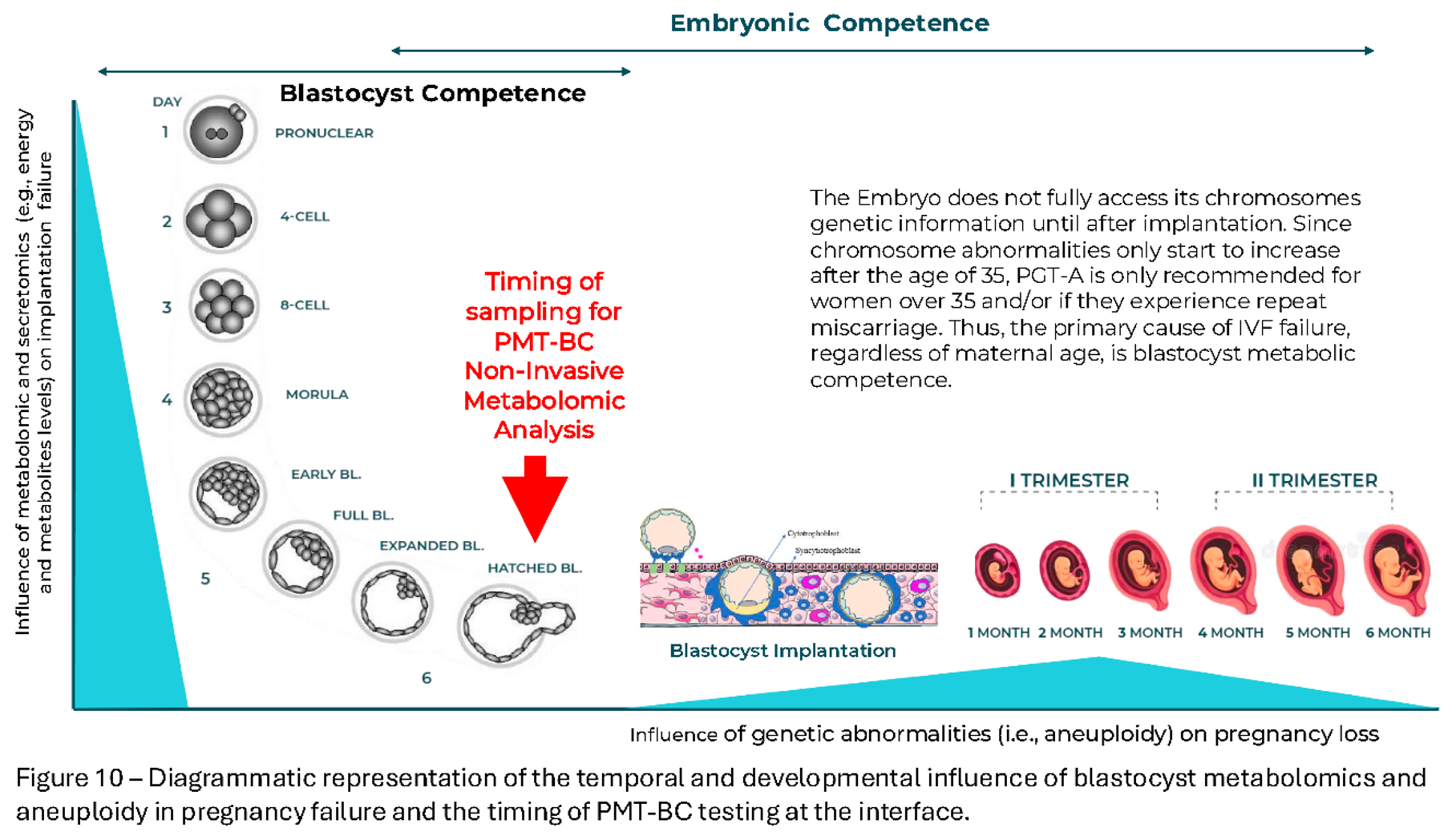

- Iles, RK, Zmuidinaite R, Iles JK, Nasser S. The influence of Hatching on blastocyst metabolomic analysis: Mass Spectral analysis of Spent blastocyst media in Ai/ML prediction of IVF Embryo implantation potential– To Hatch or not to Hatch? PREprints.org 2025. [CrossRef]

- Iles, R.K., Zmuidinaite, R., Iles, J.K., Nasser, S. The influence of defining desired outcomes on prediction algorithms: Mass Spectral analysis of Spent blastocyst media in Ai/ML prediction of IVF Embryo implantation potential – Implantation, or Viability, or both? PREprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Iles, RK, Zmuidinaite R, Iles JK, Nasser S. The development of a robust and user friendly preimplantation metabolic test of blastocyst competence. PMT-BC: Mass Spectral analysis of Spent blastocyst media in Ai/ML-Bayesian prediction of IVF Embryo implantation potential. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tesaik , J. Noninvasive Biomarkers of Human Embryo Developmental Potential PREprints.org 2025. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202504.1568/v1.

- Zmuidinaite, R.; Sharara, F. I.; Iles, R.K. “Current advancements in noninvasive profiling of the embryo culture media secretome,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2021, 22(5):2513.

- Pais, R.J.; Sharara, F.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Butler, S.; Keshavarz, S.; Iles, R. Bioinformatic identification of euploid and aneuploid embryo secretome signatures in IVF culture media based on MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020, 37(9):2189-2198. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Hamza, I., Dailey. One ring to rule them all: Trafficking of heme and heme synthesis intermediates in the metazoans. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, 2012, 1823(9): 1617-1632. [CrossRef]

- Tsiftsoglou, A.S., Athina I. Tsamadou. Heme as key regulator of major mammalian cellular functions: Molecular, cellular, and pharmacological aspects. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2006, 111(2): 327-345. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldo, S., Brunori, M., & Cutruzzola, F. Ancient hemes for ancient catalysts. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2008, 3(2):135–136. [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, S., Muramoto, K., Shinzawa-Itoh, K. The O2 reduction and proton pumping gate mechanism of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics, 2011,1807(10):1279-1286. [CrossRef]

- Margarita G. Skalnaya, Alexey A. Tinkov, Yulia N. Lobanova, Jung-Su Chang, Anatoly V. Skalny . Serum levels of copper, iron, and manganese in women with pregnancy, miscarriage, and primary infertility, Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 2019, 56:124-130. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L., Wu, N., Curtain J.C., Qatanani, M., Szxwegold N.R., Reid, R.A., Waitt, G.M., Parks, D.J., Pearce, K.H., Wisely, G.B., Lazer, M.A. Rev-erbα, a Heme Sensor That Coordinates Metabolic and Circadian Pathways. Science 2007, 318:1786-1789. [CrossRef]

- Dunaway LS, Loeb SA, Petrillo S, Tolosano E, Isakson BE. Heme metabolism in nonerythroid cells J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300(4):107132. [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, D., Fiorito, V., Petrillo, S., Bertino, F., and Tolosano, E. HEME: a neglected player in nociception? Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 2021, 124: 124–136.

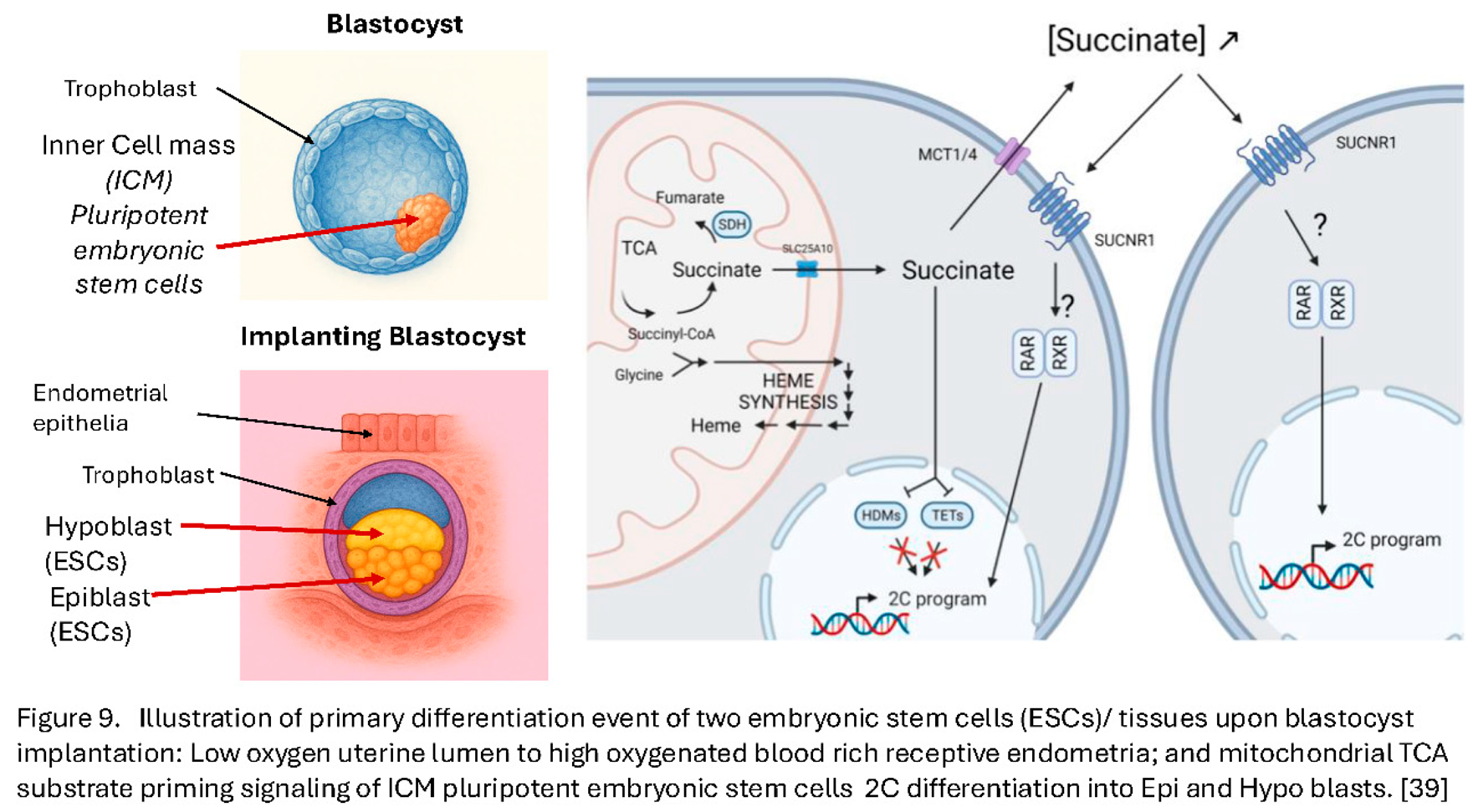

- Detraux, D., Caruso, M., Feller, L., Fransolet, M., Meurant, S., Mathieu, J., Arnould, T., Renard, P. A critical role for heme synthesis and succinate in the regulation of pluripotent states transitions. eLife 2023, 12:e78546. [CrossRef]

- Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, Manor YS,Chomsky E,Ben-Yosef D, Kalma Y, Viukov S, Maza I, Zviran A, Rais Y, Shipony Z, Mukamel Z, Krupalnik V, Zerbib M, Geula S, Caspi I, Schneir D, Shwartz T, Gilad S, Amann-Zalcenstein D, Benjamin S, Amit I, Tanay A Massarwa R, Novershtern N, Hanna JH. Derivation of novel human ground state naïve pluripotent stem cells, Nature 2013 504:282–286. [CrossRef]

- Ware CB, Nelson AM, Mecham B, Hesson J, Zhou W, Jonlin EC, Jimenez-Caliani AJ, Deng X, Cavanaugh C, Cook S, Tesar PJ, Okada J, Margaretha L, Sperber H, Choi M, Blau CA, Treuting PM, Hawkins RD, Cirulli V, Ruohola-Baker H. (2014) Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells, PNAS 2014 111:4484–4489. [CrossRef]

- Theunissen TW Friedli M He Y Planet E O’Neil RC Markoulaki S Pontis J Wang H Iouranova A Imbeault M Duc J Cohen MA Wert KJ Castanon R Zhang Z Huang Y Nery JR Drotar J Lungjangwa T Trono D Ecker JR Jaenisch R. Molecular Criteria for Defining the Naive Human Pluripotent State. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19:502–515. [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan A Kim R Chronis C Sabri S Bonora G Theunissen TW Kuoy E Langerman J Clark AT Jaenisch R Plath K. Human Naive Pluripotent Stem Cells Model X Chromosome Dampening and X Inactivation. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20:87–101. [CrossRef]

- Sperber H Mathieu J Wang Y Ferreccio A Hesson J Xu Z Fischer KA Devi A Detraux D Gu H Battle SL Showalter M Valensisi C Bielas JH Ericson NG Margaretha L Robitaille AM Margineantu D Fiehn O Hockenbery D Blau CA Raftery D Margolin AA Hawkins RD Moon RT Ware CB Ruohola-Baker H. The metabolome regulates the epigenetic landscape during naive-to-primed human embryonic stem cell transition Nature Cell Biology 2015 17:1523–1535. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W Choi M Margineantu D Margaretha L Hesson J Cavanaugh C Blau CA Horwitz MS Hockenbery D Ware C Ruohola-Baker H. HIF1α induced switch from bivalent to exclusively glycolytic metabolism during ESC-to-EpiSC/hESC transition The EMBO Journal 2012, 31:2103–2116. [CrossRef]

- Sustáčková G Legartová S Kozubek S Stixová L Pacherník J Bártová E. Differentiation-independent fluctuation of pluripotency-related transcription factors and other epigenetic markers in embryonic stem cell colonies Stem Cells and Development 2012, 21:710–720. [CrossRef]

- Macfarlan TS Gifford WD Driscoll S Lettieri K Rowe HM Bonanomi D Firth A Singer O Trono D Pfaff SL. Embryonic stem cell potency fluctuates with endogenous retrovirus activity. Nature 2012, 487:57–63. [CrossRef]

- Ishiuchi T Enriquez-Gasca R Mizutani E Bošković A Ziegler-Birling C Rodriguez-Terrones D Wakayama T Vaquerizas JM Torres-Padilla ME. Early embryonic-like cells are induced by downregulating replication-dependent chromatin assembly Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2015, 22:662–671. [CrossRef]

- Percharde M Lin CJ Yin Y Guan J Peixoto GA Bulut-Karslioglu A Biechele S Huang B Shen X Ramalho-Santos M. A LINE1-Nucleolin Partnership Regulates Early Development and ESC Identity Cell 2018, 174:391–405. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J, Scott R, Alikani M, Schimmel T, Munné S, Levron J, Wu L, Brenner C, Warner C, Willadsen S. Ooplasmic transfer in mature human oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998 4(3):269-80. [CrossRef]

- Hyslop, L., Blakeley, P., Craven, L. et al. Towards clinical application of pronuclear transfer to prevent mitochondrial DNA disease. Nature 2016 534, 383–386 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Newson AJ, Wilkinson S, Wrigley A. Ethical and legal issues in mitochondrial transfer. EMBO Mol Med. 2016 Jun 1;8(6):589-91. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Borges N, Nikitos E, Späth K, Miguel-Escalada I, Ma H, Rink K, Coudereau C, Darby H, Koski A, Van Dyken C, Mestres E, Papakyriakou E, De Ziegler D, Kontopoulos G, Mantzavinos T, Vasilopoulos I, Grigorakis S, Prokopakis T, Dimitropoulos K, Polyzos P, Vlachos N, Kostaras K, Mitalipov S, Calderón G, Psathas P, Wells D. First pilot study of maternal spindle transfer for the treatment of repeated in vitro fertilization failures in couples with idiopathic infertility. Fertil Steril. 2023 Jun;119(6):964-973. [CrossRef]

- Kang MH, Kim YJ, Lee JH. Mitochondria in reproduction. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2023 50(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Raziye Melike Yildirim, Emre Seli, Mitochondria as therapeutic targets in assisted reproduction, Human Reproduction, 2024, 39(10): 2147-2159. [CrossRef]

- Subirá J, Soriano MJ, Del Castillo LM, de Los Santos MJ. Mitochondrial replacement techniques to resolve mitochondrial dysfunction and ooplasmic deficiencies: where are we now? Hum Reprod. 2025 Apr 1;40(4):585-600. [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. ‘Landmark’ study: three-person IVF leads to eight healthy children. Long-awaited results suggest that mitochondrial donation can prevent babies from inheriting diseases caused by mutant mitochondria. Nature 2025, 643:891. [CrossRef]

- Hyslop, L.A., Blakely, E.L., Aushev, M., Marley, J., Takeda, Y., Pyle, A., Moody, E., Feeney, C., Dutton, J., Shaw, C. and Smith, S.J., 2025. Mitochondrial donation and preimplantation genetic testing for mtDNA disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 2025 393(5):438-449. [CrossRef]

- McFarland, R., Hyslop, L.A., Feeney, C., Pillai, R.N., Blakely, E.L., Moody, E., Prior, M., Devlin, A., Taylor, R.W., Herbert, M. and Choudhary, M. Mitochondrial Donation in a Reproductive Care Pathway for mtDNA Disease. N Engl J Med. 2025, 393(5):461-468.

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Use of preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic adult-onset conditions: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 122 (4): 607–611. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).