1. Introduction

In recent years, the incidence of infertility among couples has been increasing, which can be attributed to various social, biological, and biochemical factors. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines infertility as the inability of a couple to achieve pregnancy after one year of sexual intercourse without contraception [

1]. It is estimated that infertility affects between 4-14% of the population globally, making it a significant public health issue. Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) have been developed as a solution to this problem, with the WHO advocating for increased accessibility to such treatments. However, success rates of ART are still below expectations, indicating a need for further investigation into the biochemical processes involved in ART techniques, particularly during embryonic development, and the identification of biomarkers associated with ART [

2]. One of the significant challenges of ART is the optimization of embryo selection. Current methods for evaluating embryo implantation potential rely on morphological assessment, which is not always effective in predicting implantation success [

3].

Metabolomics, a quantitative and non-invasive technology, has recently emerged as a promising tool for measuring metabolites present in cells, tissues, body fluids, and culture media. By quantifying the metabolites secreted by gametes and embryos during culture, metabolomics can provide insight into embryonic viability and help identify embryonic biomarkers that may improve the outcomes of ART treatments [

4,

5]. Several studies have already established correlations between embryonic viability and carbohydrate, pyruvate, and amino acid metabolism during embryonic development [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In fact, metabolic performance in embryos after compaction has been identified as a biomarker for higher-quality blastocysts [

9,

11]. Despite these promising findings, the lack of consensus in this field largely stems from the absence of standardization in the molecular assessment of embryo quality [

12]. Therefore, this study aims to integrate metabolomics with the standardized morphological classification of embryos to identify biomarkers that can facilitate the selection of the best embryo for transfer. By combining metabolomic and standardized morphological embryo evaluations, this study can provide valuable insights into the complex metabolic processes underlying embryonic development and quality. Ultimately, the integration of metabolomics in ART can offer a powerful tool for improving treatment outcomes and identifying biomarkers associated with embryonic viability and quality. The identification of such biomarkers can greatly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of ART, leading to better pregnancy rates and improved clinical outcomes for infertile couples.

3. Discussion

The current methods for evaluation of embryo quality during

in vitro development have limitations, depending mostly on the morphological assessment by an experienced embryologist. These methodologies are subjective, and there can be inter- and intra-observer variability, which can affect the consistency of embryo grading and impact the selection of the best embryo for transfer. Moreover, morphological assessment is typically performed at specific time points during embryo development, which may not be optimal for evaluating embryo quality [

12]. Hence, morphological assessment is not always effective in predicting implantation success. Even high-quality embryos can fail to implant or result in unsuccessful pregnancies. As a result, some embryos may be misclassified, leading to lower success rates of ART treatments. In this sense, the integration of embryo metabolomics with standardized morphological classification can help address some of these limitations by providing a more comprehensive evaluation of embryo quality, including information on potential biomarkers for embryo selection [

4]. In this work, we chose to evaluate the metabolic performance of embryos during

in vitro development, which were monitored in a time-lapse incubator during a period of 5 days and subject to standardized morphokinetic categorization, according to their development.

Embryos final classification in day 5 were established by Gardner's blastocyst grading scale [

24], using the recommendations of The Istanbul Consensus mainly for observation timing and the identification of non-viable embryo [

13]. Following this classification, they were divided into Good, Lagging and Bad embryos, as described above. During the 5-day culture, we chose to correlate the embryo development status with the variation, at day 3 and day 5, of six specific metabolites that are on the crossroad of major cellular pathways: pyruvate, lactate, alanine, glutamine, acetate, and formate. Indeed, apart from glucose (whose consumption was not altered in any of our experimental conditions - data not shown), these metabolites are amongst the foremost important players of various pathways of cellular metabolism and, specifically during embryo development, and are known to be involved in energy production, biosynthesis, and signalling events [

25,

26]. Indeed, pyruvate is the end-product of the energy-yielding process of glycolysis and can be converted to acetyl-CoA, which enters the citric acid cycle to generate more ATP. Lactate and alanine are produced from pyruvate, particularly when the redox status (NAD+/NADH ratio) is altered. They can be converted back to pyruvate and generate ATP by being driven to the citric acid cycle [

27]. Acetate is produced during fatty acid metabolism and can be used as an energy source by some cells [

28]. Glutamine is an amino acid that is involved in several metabolic pathways, including the synthesis of nucleotides, proteins, and other amino acids, being also an important source of energy for rapidly dividing cells such as embryos [

29]. Formate can be derived from various pathways, including the breakdown of serine, being involved in one-carbon metabolism, which is important for the synthesis of nucleotides and other biomolecules [

30]. Studies have demonstrated that human preimplantation embryos consume and secrete these metabolites, into the surrounding culture media, indicating active metabolism and energy production [

5,

6,

12].

Based on our analysis, the adjusted metabolite differentials (for covariates such as the male age, female age, male BMI, female BMI, and ART technique) observed in the 3 first days of embryo culture are discriminative of embryo quality category at the end of day 5. The inclusion of covariates related to individual characteristics of the donors of the gametes is crucial to assess the impact of embryo culture medium metabolites in early embryo development. Although ICSI circumvents part of the individual variability, the age and BMI of the donors have been reported to influence the success rate of the ICSI [

21,

31,

32], particularly in European cohorts [

33,

34], therefore we have considered these covariates to add another layer of embryo selection. The major contributors for discriminating Good, Lagging and Bad embryos were pyruvate, alanine, glutamine, and acetate, after correcting for the confounders. Pyruvate is a critical molecule for energy metabolism in cells. In the context of embryonic development, pyruvate serves as an essential energy substrate during the preimplantation stages [

27]. Pyruvate is oxidized to produce ATP via oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria, which is the primary energy source for most cellular processes, including cell division and growth. Pyruvate also provides carbon for the biosynthesis of nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids, which are all essential for embryonic development. Pyruvate has been linked to embryo development and increased embryo quality in some species, including cattle and sheep [

35]. Although the importance of this metabolite for early embryo development has been evidenced in some studies, the role of pyruvate in human embryonic development is still less clear when other metabolic sources are present [

8,

27]. In our study, adjusted pyruvate variation in the culture media of 3-day human embryos was quite distinct in Bad embryos from Good and Lagging embryos. While Bad embryos consumed pyruvate, Good and Lagging embryos were able to export and accumulate it in the culture media, suggesting an active metabolism. A similar trend was observed for glutamine, with Good and Lagging embryos being able to export and accumulate this amino acid in the culture media, while Bad embryos consumed it. Glutamine is an important metabolite for embryo development, as it serves as a precursor for various metabolic pathways [

9]. It is a non-essential amino acid that can be synthesized by the embryo or taken up from the surrounding culture medium. Glutamine plays a crucial role in nucleotide biosynthesis, protein synthesis, and energy production in developing embryos. During early embryonic development, glutamine is predominantly utilized for energy production through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [

36]. Glutamine is converted to glutamate, which is then further metabolized to produce energy in the form of ATP. Additionally, glutamine is a precursor for the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, which are necessary for DNA and RNA synthesis during embryonic development [

37]. Studies have shown that the addition of glutamine to the culture medium during

in vitro embryo development can improve embryo quality and blastocyst formation rates [

38]. This suggests that glutamine plays an important role in embryonic metabolism and development [

29]. Human embryos have been shown to export glutamine during in vitro development [

11].

In vitro studies have shown that the usage of glutamine by embryos increases during the blastocyst stage and that the export of glutamine is associated with increased cell proliferation and blastocyst formation [

39], as observed in our experimental work.

Alanine is a non-essential amino acid that plays an important role in the metabolism of developing embryos. During embryonic development, alanine is involved in the synthesis of proteins, the regulation of glucose metabolism, and the maintenance of cellular redox balance [

40]. Studies have shown that alanine is an important nutrient for embryonic growth and development [

40]. Data has shown that the availability of alanine can affect the developmental potential of embryos, with lower levels of alanine associated with decreased embryo quality and lower rates of implantation [

39]. In our work, up until day 3, Bad embryos produce significantly lower amounts of alanine than Good or Lagging embryos. In fact, during development, the embryo has been shown to produce and export alanine to the surrounding environment, with embryos that produce and export higher levels of alanine having better developmental potential and being linked to higher pregnancy rates [

5]. The export of alanine by human embryos is significant because it reflects the metabolic state of the embryo and its ability to maintain energy balance during early development. It has been suggested that the export of alanine may serve as a protective mechanism against stress and nutrient deprivation, allowing the embryo to maintain its viability and developmental potential [

41]. Contrastingly, as concerning acetate, both Bad and Lagging embryos showed a different trend from that of Good embryos in the variation of this short-chain fatty acid in culture media. While Bad embryos produced higher amounts of acetate in our experimental conditions, Lagging embryos consumed it. Acetate has been shown to be an important energy source for embryo development [

6]. This short-chain fatty acid can be derived from the metabolism of glucose or other substrates. It can also enter the embryo through the surrounding culture media and be transported into the mitochondria, where it can undergo oxidation to produce ATP. Acetate can also be incorporated into the synthesis of lipids, which are essential components of cell membranes [

42]. As the embryo develops and the number of cells increases, the demand for energy also increases, and the embryo begins to utilize other energy sources, including acetate [

6]. It has been shown that acetate is critical for proper embryo development, as it enhances cell growth and division, regulates gene expression, and improves embryonic quality, particularly for embryos during the pre-implantation period [

35]. Overall, the higher amounts of acetate observed in the culture media of Bad embryos at the end of day 3 should be due to lower utilization of this metabolite due to the poor development of these embryos. The significance of the consumption of acetate by Lagging embryos is unclear, but it may reflect the need to increase the metabolic rates of these cells to enhance the formation of blastocysts.

As a remark, and although no differences were observed in the variation of formate in any of the experimental conditions used, it is of note that our embryos consistently exported significant amounts of this monocarboxylic acid anion. It is known that mammalian cells generate formate as a byproduct of various metabolic reactions, including the breakdown of certain amino acids and the metabolism of folate. Formate is then either excreted from the cell or used in various biosynthetic pathways, including the synthesis of purines, pyrimidines, and amino acids. In addition, formate can also play a role in regulating cellular redox balance and oxidative stress. For example, formate has been shown to protect cells from oxidative damage by acting as an antioxidant. Overall, the cellular significance of formate in mammalian cells is diverse and multifaceted, with important roles in both metabolism and cellular defense mechanisms [

30]. During early embryonic development, formate is produced by the mitochondria and is used as a source of one-carbon units for nucleotide synthesis and methylation reactions [

7]. Formate is the main one-carbon donor for de novo purine biosynthesis in the developing embryo. It has been shown that the inhibition of formate metabolism in early embryos can lead to developmental defects and reduced viability [

43]. In fact, some studies suggested formate levels as a biomarker for embryonic viability in ART, as the concentration of formate in the culture media can be linked to the metabolic activity of the embryo and in some conditions can be indicative of embryonic viability and quality.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

Embryo and gamete culture media and reagents were purchased from Origio®, (Denmark), Nidacon (Sweden) and Vitrolife (Sweden). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless stated otherwise.

4.2. Patient selection and Ovarian Stimulation

Twenty-one couples (that underwent a total of 21 cycles) were involved in this study underwent treatment of Assisted Reproductive Therapy (ART) at Centro de Genética Prof. Alberto Barros (CGR), Porto, Portugal between June 2019, and February 2021. The procedures of the Centre for Reproductive Genetics Alberto Barros are covered by the provisions of the National Medically Assisted Procreation Act (2017) and overseen by the National Council for Medically Assisted Procreation (CNPMA-2018). According to these rules and guidelines, the use of clinical databases and patient biological material for diagnosis and research may be used without further ethical approval, under strict individual anonymity, and after patient written informed consent. Regarding the use of human samples for laboratory experimentation, the Ethics Committee authorization number is 2021/CE/P02 (P342/2021/CETI), approved on 26 February 2021. The inclusion criteria were couples who were referred to infertility treatment with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) technique since the need to avoid the interference of cumulus cell or spermatozoa during metabolomics quantification. The couple was excluded from the study if they had a testicular biopsy performed (testicular sperm aspiration or testicular sperm extraction) or cryopreserved ejaculated spermatozoa. So, all the ICSI were performed with fresh ejaculated spermatozoa. Semen samples were collected on the day of oocyte retrieval by masturbation. The clinical procedures and laboratory protocols were performed following the CGR standard protocols. Controlled ovarian stimulation was performed using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol (GnRH-ant). Recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH - follitropin alfa: Bemfola®, Gedeon Richter, Hungary and Gonal F®, Merck-Serono, Netherlands; follitropin beta: Puregon®, MSD Biotech B.V., Netherlands), recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone with recombinant luteinizing hormone (rFSH and rLH in a 2:1 ration - Pergoveris®, Merck-Serono, Netherlands), menotropin (highly purified human menopausal gonadotrophin, hMG - Menopur®, Ferring Pharmaceutical, Spain) or corifollitropin alpha (Elonva®, N.V. Organon, Netherlands) were used to stimulate ovaries with initial doses based on the individual characteristics of patients. Beyond day 6 and when the leading follicle reaches 12 mm, treatment was continued with gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist ganirelix (Orgalutran®, N.V. Organon, The Netherlands) or cetrorelix acetate (Cetrotide®, Merck-Serono, The Netherlands) until final follicular maturation. Stimulation was prolonged until the observation by ultrasound of at least three dominant follicles of 17 mm or greater in diameter or, in cases of a low number of growing follicles, at least one. The final oocyte maturation was triggered with 250 μg of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (rhCG - choriogonadotropin alfa; Ovitrelle®, Merk Serono, The Netherlands;) or 0.2 mg of GnRH agonist (Triptorelin acetate, Decapeptyl®, Ipsen Pharma, Spain) or both. The serum hormone levels of estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P) were evaluated on the day of the trigger. Transvaginal oocyte retrieval was performed 36 h after the final follicular maturation.

4.3. Gamete collection

After liquefaction, sperm concentration and progressive motility were assessed according to World Health Organization [

51]. The semen preparation standard protocol included a discontinuous density gradient of 90-45% centrifugation (PureSperm®, Nidacon, Sweden) followed by a swim-up protocol with fertilization medium (Sequential Fert™, Origio®, Denmark). In cases of severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia the sperm sample was only washed with a sperm preparation medium (Sperm Preparation Medium, Origio®, Denmark) followed by a swim-up protocol with fertilization medium (Sequential Fert™, Origio®, Denmark). The final sperm preparation was incubated at 35°C with 6% O

2 at least 30 minutes before the beginning of the ICSI procedure. After the follicular aspiration, the oocyte-cumulus complexes (OCCs) were isolated and washed in gamete preparation medium (SynVitro™ Flush, Origio®, Denmark). The retrieved OCCs were placed into a 5-well dish with 250 μL fertilization medium (Sequential Fert™, Origio®, Denmark) covered with oil (OVOIL™, Vitrolife, Sweden) which has been previously equilibrated overnight (37°C, 5%CO2 and 6% O2). OCCs were denuded to evaluate oocyte nuclear maturity. So, 2 hours after egg retrieval, cumulus cells were removed using a combination of mechanic and enzymatic (ICSI Cumulase®, Origio®, Denmark) denudation protocol.

4.4. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and embryo culture

Four hours after egg retrieval, oocytes were injected following the standard ICSI procedure. Injected oocytes were rinsed and placed individually in a 25 μL drop of culture medium (Sequential Cleav™, Origio®, Denmark) under oil (OVOIL™, Vitrolife, Sweden) which was previously equilibrated overnight in an incubator with 37°C, 5% CO2 and 6% O2. The culture dish (EmbryoSlide®, Vitrolife, Sweden) allows an individualized oocyte/embryo culture with no connection between the culture medium of adjacent oocytes/embryos. The culture dish was placed in a time-lapse incubator (EmbryoScope®, Vitrolife, Sweden) for the following assessment (Day 0). Normal fertilization was confirmed 16-18 h after ICSI by the presence of two pronuclei and a second polar body (Day 1). Embryo culture was extended until the blastocyst stage (day 5/6). The standard laboratory protocol applied uses a sequential culture media. The embryos were cultured in cleavage medium (Sequential Cleav™, Origio®, Denmark) until day 3 and then the culture media were replaced for blastocyst medium (Sequential Blast™, Origio®, Denmark) to support embryo culture until the blastocyst stage (day 5).

4.5. Embryo morphology assessment

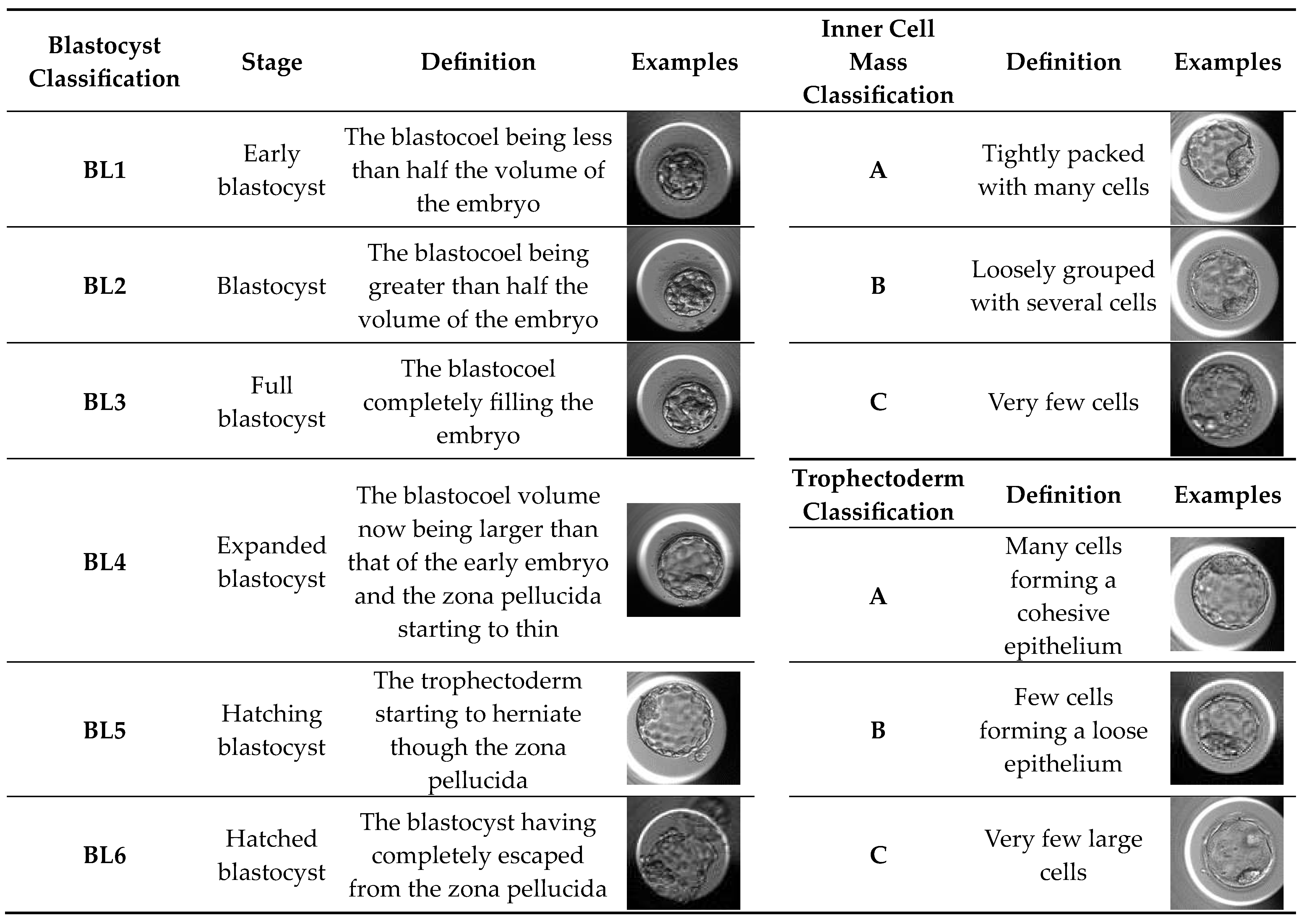

Development of each embryo was evaluated from fertilization until day 5 in a time-lapse system (Vitrolife, Sweden). Routine observation of cleavage embryos (until day 4) mainly includes the number and symmetry of blastomeres, fragmentation percentage and presence of multinucleated blastomeres (day 2/3) and compactation grade (day 4). Cleavage embryos were scored according to four categories (A, B, C and D), based solely on blastomeres number and fragmentation [

52]. The blastocysts were graded according to Gardner Score System [

24]. This scoring system uses a number associated with a letter and this combination allows us to know the blastocyst stage and blastocyst quality. Initially, the classification is based on the degree of expansion and hatching status of blastocysts, and the numeric score from 1 to 6 reflects the blastocyst stage (

Table 4). For blastocysts scored from 3-6 the classification system includes the development of the inner cell mass and trophectoderm (

Table 4). A good quality blastocyst was considered as 3BB or better.

4.6. Sample Collection/Preparation

As mentioned before, the use of sequential media in an embryo culture implies that until day 3 the embryos are cultured in a cleavage medium and afterwards there must be a change in culture medium to support embryo development until day 5 (blastocyst stage). So, for each embryo used for the study, there will be two samples of culture medium: a sample of cleavage media (Day 0 until day 3 of embryo development) and a sample of blastocyst medium (Day 3 until day 5 of embryo development). Sample collection was carried out by pipetting 20 μL out of the 30 μL drop of culture media into microcentrifuge tubes. Each sample (20 μL) was obtained from the spent culture media of embryos developed from day 0 (after ICSI) until day 3 and from day 3 until day 5/6. To be used as controls, samples from the same corresponding batch of the medium used in embryo culture were collected. All samples were stored in a refrigerator at –80°C until metabolomic analysis.

4.7. Metabolomic analysis by 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

1D 1H-NMR spectroscopy was used to identify and quantify metabolites in the embryo culture media. NMR spectra were acquired using a 600 MHz VNMRS spectrometer (Varian, Inc. Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with a 3 mm indirect detection probe. 140 µL of deuterium oxide and 40 µL of sodium fumarate solution (final concentration of 2 mM) were added to 20 µL of each embryo culture media, and the final volume of 200 µL was transferred into a 3 mm NMR tube for analysis. Sodium fumarate was used as an internal reference (6.50 ppm) to quantify the following metabolites (multiplicity, ppm): alanine (doublet, 1.46), acetate (singlet, 1.90), pyruvate (singlet, 2.35), glutamine (multiplet, 2.45), lactate (quartet, 4.09), formate (singlet, 8.40). NMR spectra were processed by applying exponential line broadening (0.2 Hz), baseline correction, and manual phasing, and the areas of the resonances were quantified using the NUTSproTM NMR Software (Acorn, Fremont, CA, USA).

4.8. Statistical analysis

Univariate statistics were used to compare embryo culture medium metabolite differential in days 0-3 (D3) and 3-5 (D5) between embryos grouped by their assessed quality at day 5 (Good vs. Lagging vs. Bad). Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D.). Embryo quality was assessed by the same trained and experienced embryologist. Normality and heteroscedasticity tests were performed, and Univariate ANOVA was conducted on selected metabolites identified in the embryo culture medium. Pairwise comparisons between groups were corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Tukey’s

post hoc test. Multivariate analysis of metabolite consumption/production was performed using a linear model integrating corrections for confounding factors. Metabolite differentials in days 0-3 (D3) and 3-5 (D5) were compared between embryos grouped by their assessed quality at day 5 (Good vs. Lagging vs. Bad) using Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA), after controlling for covariates (male age, female age, male BMI, female BMI). These covariates were chosen based on multiple studies correlating maternal age [

14,

16] and BMI [

18,

19], and paternal age [

20] and BMI [

21,

23] with changes in early embryo metabolism and viability [

17,

22]. The assumptions of equality of the variance-covariance matrices were evaluated using Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variances and Box’s Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices (Box’s M). The discriminant value of the independent variable (embryo quality at day 5) considering the dependent variables (metabolite differential) was evaluated according to Roy’s Largest Root criterion. This method was chosen as it is the most sensitive when a limited number of dependent variables is responsible for the differences between groups of the independent variable [

53]. The impact of each metabolite differential on embryo quality at day 5 was assessed using a univariate F-test, after adjusting for the covariates. Pairwise comparisons between groups were corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Šidak’s method. All statistical tests of hypotheses for all statistical methods were performed at the α = 0.05 level using SPSS Statistics 28.0.0 for Windows 64-bit (IBM, Armonk, NY, US).

5. Conclusions

The integration of metabolomics with the standardized assessment of embryonic viability and quality is important for several reasons. For once, metabolomics allows for the non-invasive and real-time monitoring of the metabolic state of embryos during culture, which can provide valuable information on embryonic viability and quality. This is particularly important because current methods for evaluating embryo implantation potential, such as morphological assessment and morphokinetics analyses have limitations in predicting implantation success. Metabolomics can provide additional information on the metabolic activity of embryos, which may be predictive of implantation success. Second, the integration of metabolomics with the standardized morphological evaluation of embryos can lead to the identification of biomarkers associated with embryonic viability and quality. By identifying these biomarkers, it may be possible to select the best embryo for transfer, thereby increasing the chances of a successful pregnancy. Our strategy, however, does not account for metabolic differences between inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm. Previous reports have shown that metabolic rate, based on mitochondrial membrane potential and activity, is distinct between ICM and trophectoderm cells [

44,

45]. Moreover, the metabolic activity of ICM cells was suggested to play a role in embryo development [

45,

46]. Yet, The methods applied in these studies destroy or compromise the viability of the embryos. Another non-destructive technique was suggested by Alegre et al. [

47], using Raman spectroscopy. In this study, the authors use Raman’s scattering principle to estimate the total oxidant content of the used embryo culture medium at day 5. Based on this metric, the authors calculate a metabolic score to group embryos into 6 categories [

47]. Despite the reported increase in implantation rates, this technique requires a longer sample processing, adds external variability due to molecule-specific oxidation rate, and is not as specific as NMR or MS spectroscopy. A potential compromise between structure specificity and embryo viability can be achieved by

in vivo NMR, as this technology evolves fast in both resolution and sensitivity. In fact, NMR spectroscopy of a single early-stage mammalian embryo has been published recently [

48]. Presently, metabolic screening of the embryo and of the culture medium is still not routinely performed in ART clinics despite accumulated evidence of the potential benefits for nearly a decade [

49,

50].

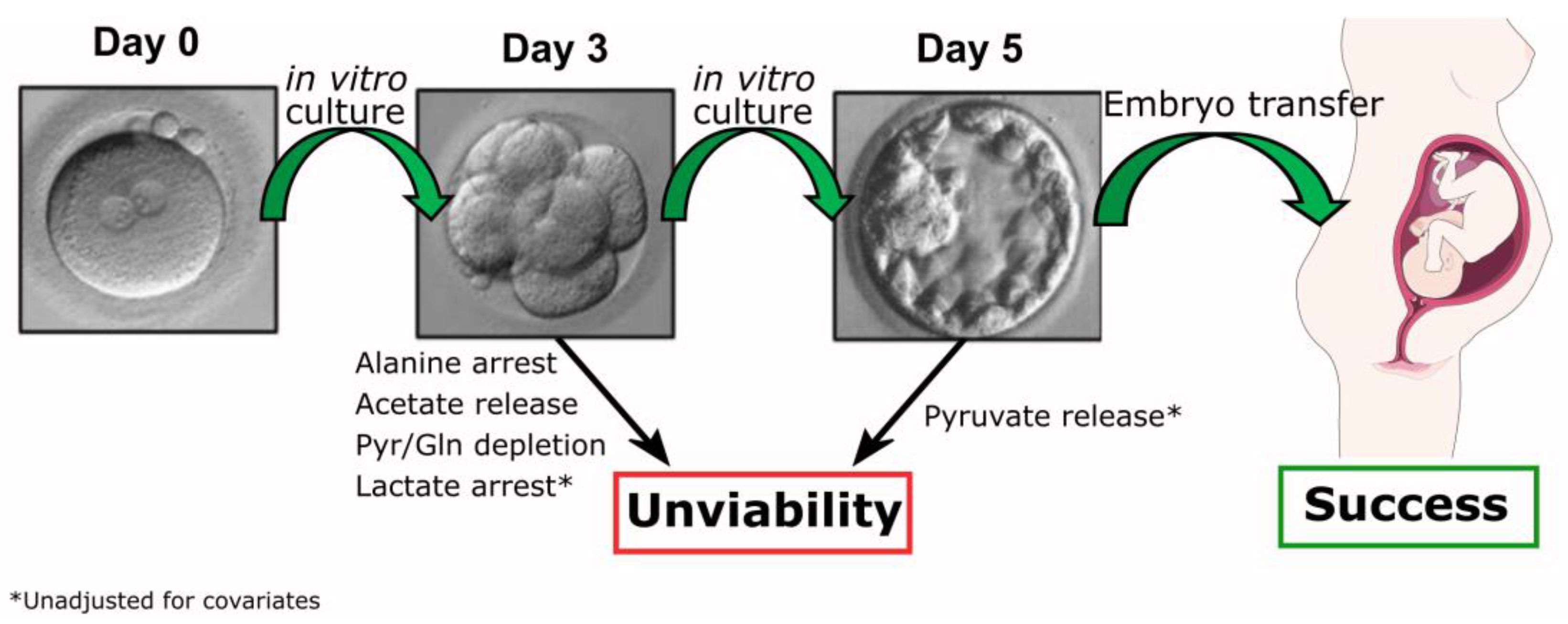

Overall, our results support that assessment of the exometabolome of

in vitro cultured human embryos up to day 3 can be discriminative of embryo quality category at day 5. Notably, the metabolite profile at day 3 is particularly selective between Lagging and Bad quality embryos, whereas the metabolite profile of Good embryos is not different from Lagging embryos (except for alanine) at this stage. However, at day 5, lactate is a potential predictor between Good and Lagging embryos. Therefore, the corrected variations (for interfering covariates such as the male age, female age, male BMI, and female BMI) of metabolites such as alanine, pyruvate, acetate, and glutamine support that the integration of metabolomics with the standardized assessment of embryonic viability and quality has the potential to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of ART (

Figure 4), leading to better pregnancy rates and improved clinical outcomes.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of testicular steroidogenesis that occurs in the Leydig cell. Luteinizing Hormone (LH) binds to its receptor (LHR) kicking off the cAMP-PKA (cyclic adenosine monophosphate - protein kinase A) pathway that leads to the release of cholesterol from its cellular reservoirs. Then, cholesterol enters the mitochondria, via Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory protein (StAR) and Peripheral-type Benzodiazepine Receptor (PBR), where it is converted to pregnenolone (Preg). Next, Pregnelone is transported to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, where the remaining steroidogenic reactions occur. The classical pathway has testosterone as an end-product, which diffuses into the extracellular medium.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of testicular steroidogenesis that occurs in the Leydig cell. Luteinizing Hormone (LH) binds to its receptor (LHR) kicking off the cAMP-PKA (cyclic adenosine monophosphate - protein kinase A) pathway that leads to the release of cholesterol from its cellular reservoirs. Then, cholesterol enters the mitochondria, via Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory protein (StAR) and Peripheral-type Benzodiazepine Receptor (PBR), where it is converted to pregnenolone (Preg). Next, Pregnelone is transported to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, where the remaining steroidogenic reactions occur. The classical pathway has testosterone as an end-product, which diffuses into the extracellular medium.

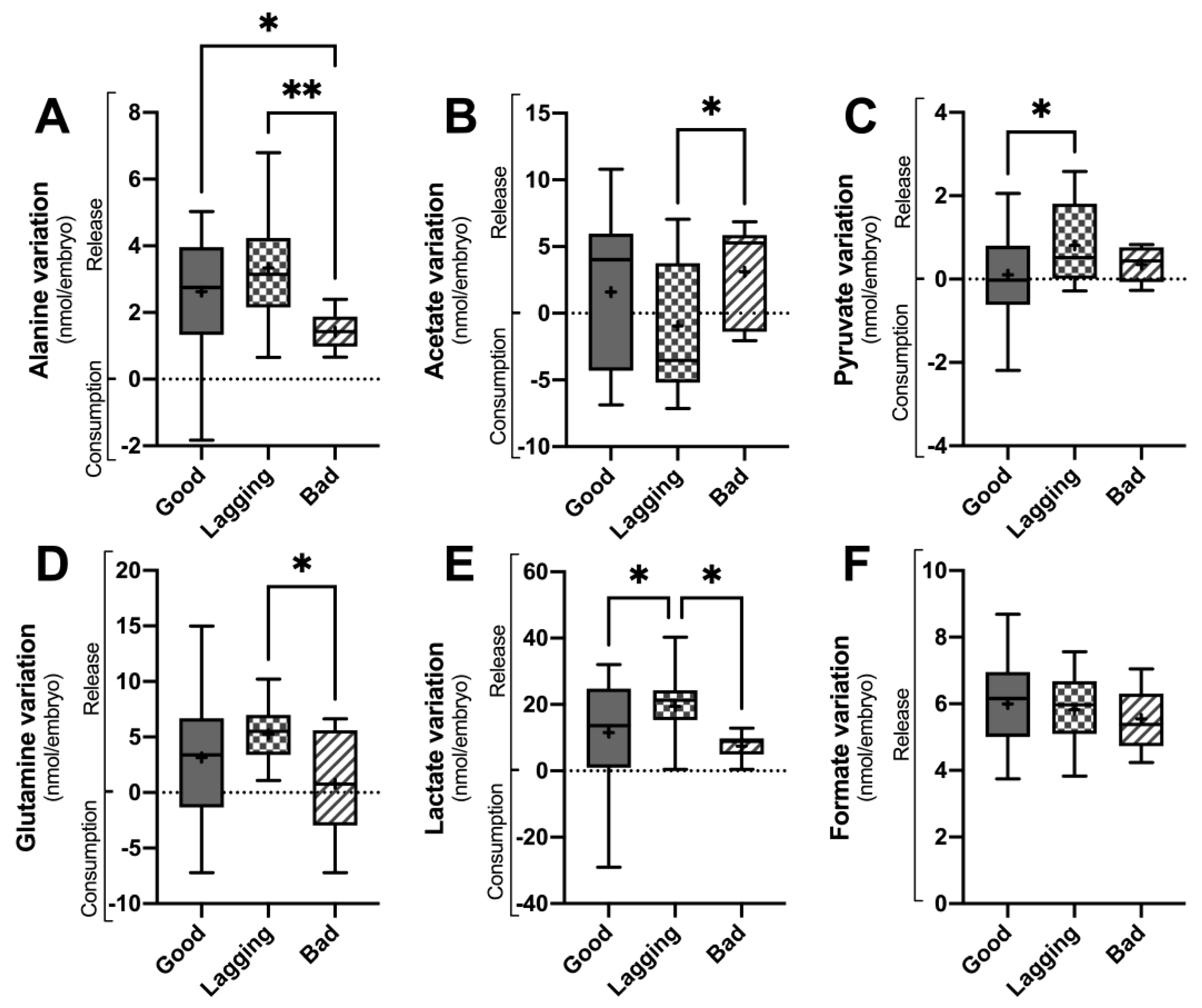

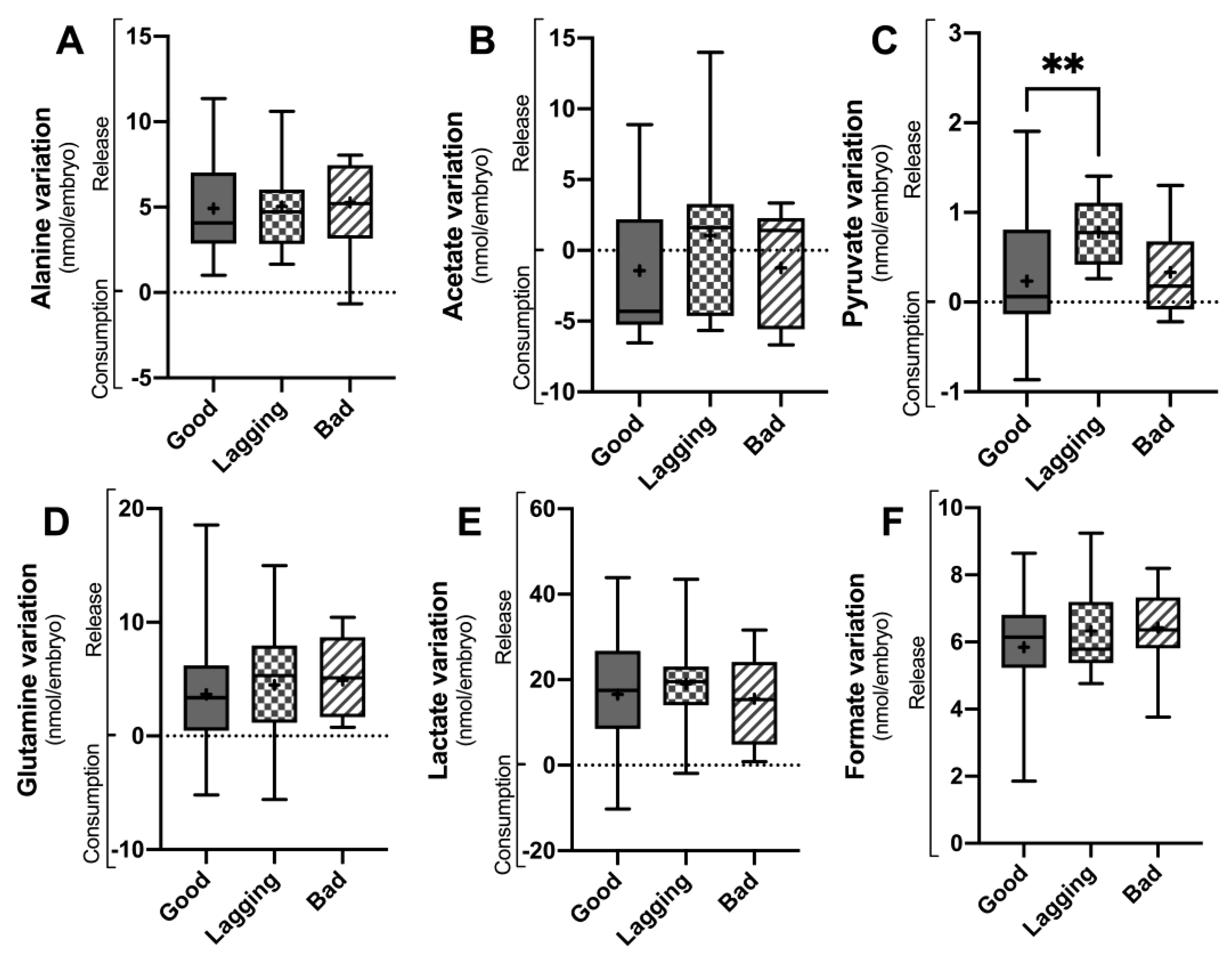

Figure 2.

Metabolite variation in culture media of human embryos between day 5 (D5) and day 3 grouped according to their quality at day 5 (Good vs. Lagging vs. Bad). The figure shows the variation (Consumption or Release) of selected metabolites (Panel A – alanine; Panel B – Acetate; Panel B – Pyruvate; Panel D – Glutamine; Panel E – Lactate; Panel F – Formate) quantified in the embryo culture media at the end of day 5 (n=55). Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D.). Normality and heteroscedasticity tests were performed, and Univariate ANOVA was conducted on the selected metabolites identified in the embryo culture medium. Pairwise comparisons between groups were corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Tukey’s post hoc test. All p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (∗∗ - p<0.005).

Figure 2.

Metabolite variation in culture media of human embryos between day 5 (D5) and day 3 grouped according to their quality at day 5 (Good vs. Lagging vs. Bad). The figure shows the variation (Consumption or Release) of selected metabolites (Panel A – alanine; Panel B – Acetate; Panel B – Pyruvate; Panel D – Glutamine; Panel E – Lactate; Panel F – Formate) quantified in the embryo culture media at the end of day 5 (n=55). Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D.). Normality and heteroscedasticity tests were performed, and Univariate ANOVA was conducted on the selected metabolites identified in the embryo culture medium. Pairwise comparisons between groups were corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Tukey’s post hoc test. All p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (∗∗ - p<0.005).

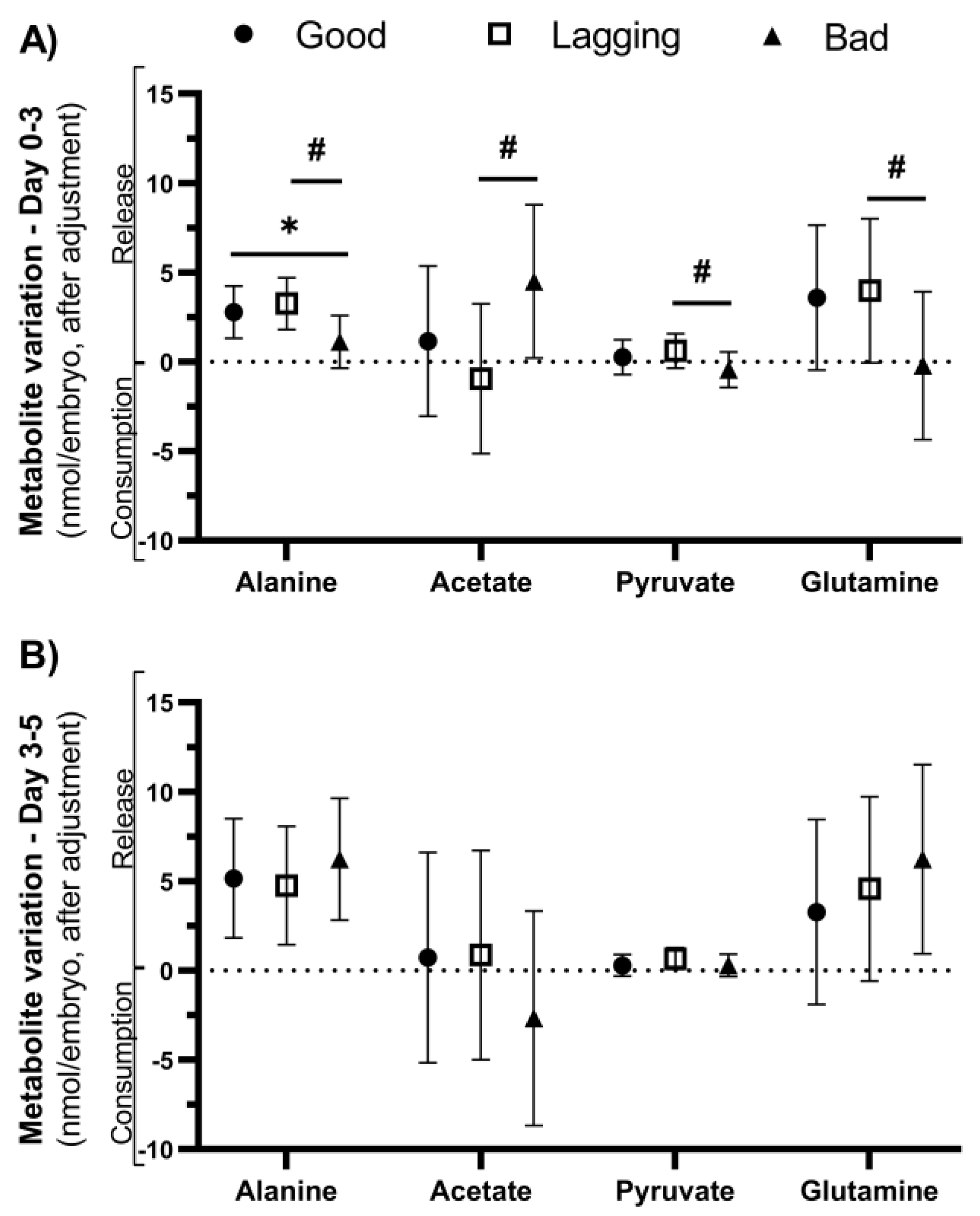

Figure 3.

Metabolite variation observed on the first 3 days (D 0-3) and from day 3 to day 5 (D 3-5) in culture media of human embryos grouped according to their quality (Good vs. Lagging vs. Bad). The figure shows the metabolite differentials of relevant metabolites (Alanine, Acetate, Pyruvate, Glutamine) observed on the first 3 days (Panel A) and from day 3 to day 5 (Panel B) (n=55). Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D.). The impact of each metabolite differential on embryo quality at day 5 was assessed using a univariate F-test, after adjusting for the covariates. Pairwise comparisons between groups were corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Šidak’s method. All p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (∗ - vs Good embryos; # - vs Lagging embryos).

Figure 3.

Metabolite variation observed on the first 3 days (D 0-3) and from day 3 to day 5 (D 3-5) in culture media of human embryos grouped according to their quality (Good vs. Lagging vs. Bad). The figure shows the metabolite differentials of relevant metabolites (Alanine, Acetate, Pyruvate, Glutamine) observed on the first 3 days (Panel A) and from day 3 to day 5 (Panel B) (n=55). Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D.). The impact of each metabolite differential on embryo quality at day 5 was assessed using a univariate F-test, after adjusting for the covariates. Pairwise comparisons between groups were corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Šidak’s method. All p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (∗ - vs Good embryos; # - vs Lagging embryos).

Figure 4.

Metabolite variation in human embryo culture medium is a predictor of successful pregnancy in ARTs. Embryo metabolism is indirectly assessed by comparison of metabolite concentration in culture medium before and after incubation. We observed that poor quality embryos at post-fertilization day 5 displayed already anomalies in alanine, acetate, pyruvate, and glutamine metabolism especially compared to embryos classified as lagging at day 5. These differences were found after adjusting for covariates (male age, female age, male BMI, female BMI). Considering unadjusted variables, lactate is another potential success predictor for ART at day 3. On day 5, considering unadjusted variables, net-zero pyruvate is a feature of good quality embryos.

Figure 4.

Metabolite variation in human embryo culture medium is a predictor of successful pregnancy in ARTs. Embryo metabolism is indirectly assessed by comparison of metabolite concentration in culture medium before and after incubation. We observed that poor quality embryos at post-fertilization day 5 displayed already anomalies in alanine, acetate, pyruvate, and glutamine metabolism especially compared to embryos classified as lagging at day 5. These differences were found after adjusting for covariates (male age, female age, male BMI, female BMI). Considering unadjusted variables, lactate is another potential success predictor for ART at day 3. On day 5, considering unadjusted variables, net-zero pyruvate is a feature of good quality embryos.

Table 1.

Characterization of studied population and of fertilization cycles.

Table 1.

Characterization of studied population and of fertilization cycles.

| Baseline characteristics of studied population |

|

Patient cycle characteristics |

| Number of couples |

21 |

|

Fertilization Technique (%) |

|

| Number of cycles |

21 |

|

ICSI |

100 (21/21) |

| Female Age (years) |

35.05 ± 6.59 |

|

Stimulation duration (days) |

9.29 ± 1.38 |

| Female Body mass index (kg/m2) |

23.59 ± 3.49 |

|

FSH total dose (IU) |

2827±1245 |

| Male Age (years) |

40.71 ± 5.49 |

|

Serum E2 on trigger day (pg/mL) |

2481 ±1486 |

| Male Body mass index (kg/m2) |

24.84 ± 5.82 |

|

Serum Pr on trigger day (ng/mL) |

0.95 ± 0.46 |

| Infertility duration (months) |

49.86 ± 32.29 |

|

Oocytes retrieved (n) |

8.48 ± 2.66 |

| Previous IVF attempts (%) |

|

|

Metaphase II oocytes (n) |

7.43 ± 2.31 |

| 0 |

42.9 (9/21) |

|

Maturation rate (%) |

85.2 ± 14.4 |

| 1 |

23.8 (5/21) |

|

Fertilized oocytes (n) |

6.33 ±2.46 |

| 2 |

19.0 (4/21) |

|

Fertilization rate (%) |

85.20 ±14.38 |

| ≥ 3 |

14.3 (3/21) |

|

Embryo Stage |

|

| Types of infertility (%) |

|

|

Day 3 embryos (n) |

6.14 ± 2.5 |

| Primary infertility |

66.7 (14/21) |

|

Day 5 embryos (n) |

4.95 ± 2.41 |

| Secondary infertility |

33.3 (7/21) |

|

Cleavage rate (%) |

96.7 ± 7.1 |

| Anti-Müllerian hormone (ng/mL) |

4.02 ± 4.34 |

|

Embryo utilization rate (%) |

53.6 ± 21.5 |

| Total number of embryos |

55 |

|

Embryo Transfers (%) |

92.9 (13/14) |

| Good |

26 |

|

1 embryo transferred |

69.2 (9/13) |

| Lagging |

19 |

|

2 embryos transferred |

30.8 (4/13) |

| Bad |

10 |

|

Freeze All Cycles |

7.1 (1/14) |

| |

|

|

Biochemical pregnancy (%) |

61.5 (8/13) |

| |

|

|

Clinical pregnancy (%) |

61.5 (8/13) |

Table 2.

Metabolite variation in embryo culture media. Metabolite variation observed on the first 3 days (Day 3) and from day 3 to day 5 (Day 5) in culture media of human embryos grouped according to their quality (Good, Lagging & Bad).

Table 2.

Metabolite variation in embryo culture media. Metabolite variation observed on the first 3 days (Day 3) and from day 3 to day 5 (Day 5) in culture media of human embryos grouped according to their quality (Good, Lagging & Bad).

Metabolite

(nmol/embryo) |

Metabolite variation in embryo culture media |

| Day 3 |

Day 5 |

| Good |

Lagging |

Bad |

Good |

Lagging |

Bad |

| Alanine |

2.63 ± 1.68 |

3.34 ± 1.65 |

1.42 ± 0.57*,#

|

4.92 ± 2.83 |

5.05 ± 2.62 |

5.27 ± 2.70 |

| Acetate |

1.59 ± 5.23 |

-0.94 ± 4.98 |

3.11 ± 3.66#

|

-1.43 ± 4.44 |

1.04 ± 5.78 |

-1.24 ± 4.16 |

| Pyruvate |

0.10 ± 1.23 |

0.81 ± 0.94* |

0.35 ± 0.42 |

0.23 ± 0.67 |

0.78 ± 0.38 |

0.33 ± 0.57 |

| Glutamine |

3.16 ± 4.94 |

5.24 ± 2.69 |

0.80 ± 4.66#

|

3.10 ± 4.47 |

4.48 ± 5.65 |

4.90 ± 3.42 |

| Lactate |

11.55 ± 15.05 |

19.44 ± 9.05* |

7.49 ± 3.99#

|

16.60 ± 13.27 |

19.03 ± 10.39 |

15.55 ± 10.99 |

| Formate |

6.00 ± 1.18 |

5.82 ± 1.06 |

5.54 ± 0.94 |

5.85 ± 1.51 |

6.33 ± 1.21 |

6.43 ± 1.23 |

Table 3.

Metabolite variation in embryo culture media. Metabolite variation observed on the first 3 days (Day 3) and from day 3 to day 5 (Day 5) in culture media of human embryos grouped according to their quality (Good, Lagging & Bad).

Table 3.

Metabolite variation in embryo culture media. Metabolite variation observed on the first 3 days (Day 3) and from day 3 to day 5 (Day 5) in culture media of human embryos grouped according to their quality (Good, Lagging & Bad).

Metabolite

(nmol/embryo) |

Adjusted metabolite variation in embryo culture mediaa

|

| Day 3 |

Day 5 |

| Good |

Lagging |

Bad |

Good |

Lagging |

Bad |

| Alanine |

2.78 ± 1.45 |

3.25 ± 1.44 |

1.11 ± 1.48*,#

|

5.15 ± 3.33 |

4.75 ± 3.32 |

6.22 ± 3.40 |

| Acetate |

1.15 ± 4.20 |

-0.95 ± 4.19 |

4.50 ± 4.29#

|

0.72 ± 5.88 |

0.86 ± 5.86 |

-2.67 ± 6.00 |

| Pyruvate |

0.25 ± 0.97 |

0.61 ± 0.97 |

-0.45 ± 0.99#

|

0.28 ± 0.61 |

0.66 ± 0.61 |

0.29 ± 0.62 |

| Glutamine |

3.59 ± 4.05 |

3.98 ± 4.03 |

-0.22 ± 4.14#

|

3.27 ± 5.18 |

4.57 ± 5.15 |

6.22 ± 5.28 |

| Lactate |

13.07 ± 12.13 |

14.69 ± 12.08* |

4.09 ± 12.38#

|

18.26 ± 17.04 |

15.00 ± 16.96 |

17.21 ± 17.38 |

| Formate |

5.10 ± 2.36 |

4.81 ± 2.34 |

5.39 ± 2.41 |

5.37 ± 2.54 |

5.26 ± 2.53 |

5.90 ± 2.59 |

Table 4.

Classification of Blastocysts, Inner Cell Mass and Trophectoderm. Degree of expansion and hatching status of blastocysts. Gardner blastocysts grade system was assessed as indicated in the table. Inner cell mass and trophectoderm classification for onward full blastocyst stage (BL3 a BL6).

Table 4.

Classification of Blastocysts, Inner Cell Mass and Trophectoderm. Degree of expansion and hatching status of blastocysts. Gardner blastocysts grade system was assessed as indicated in the table. Inner cell mass and trophectoderm classification for onward full blastocyst stage (BL3 a BL6).