Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. SNCA Biology and Physiological Role

2.2. Misfolding and Aggregation in Disease

2.3. Concept of Protein Strains

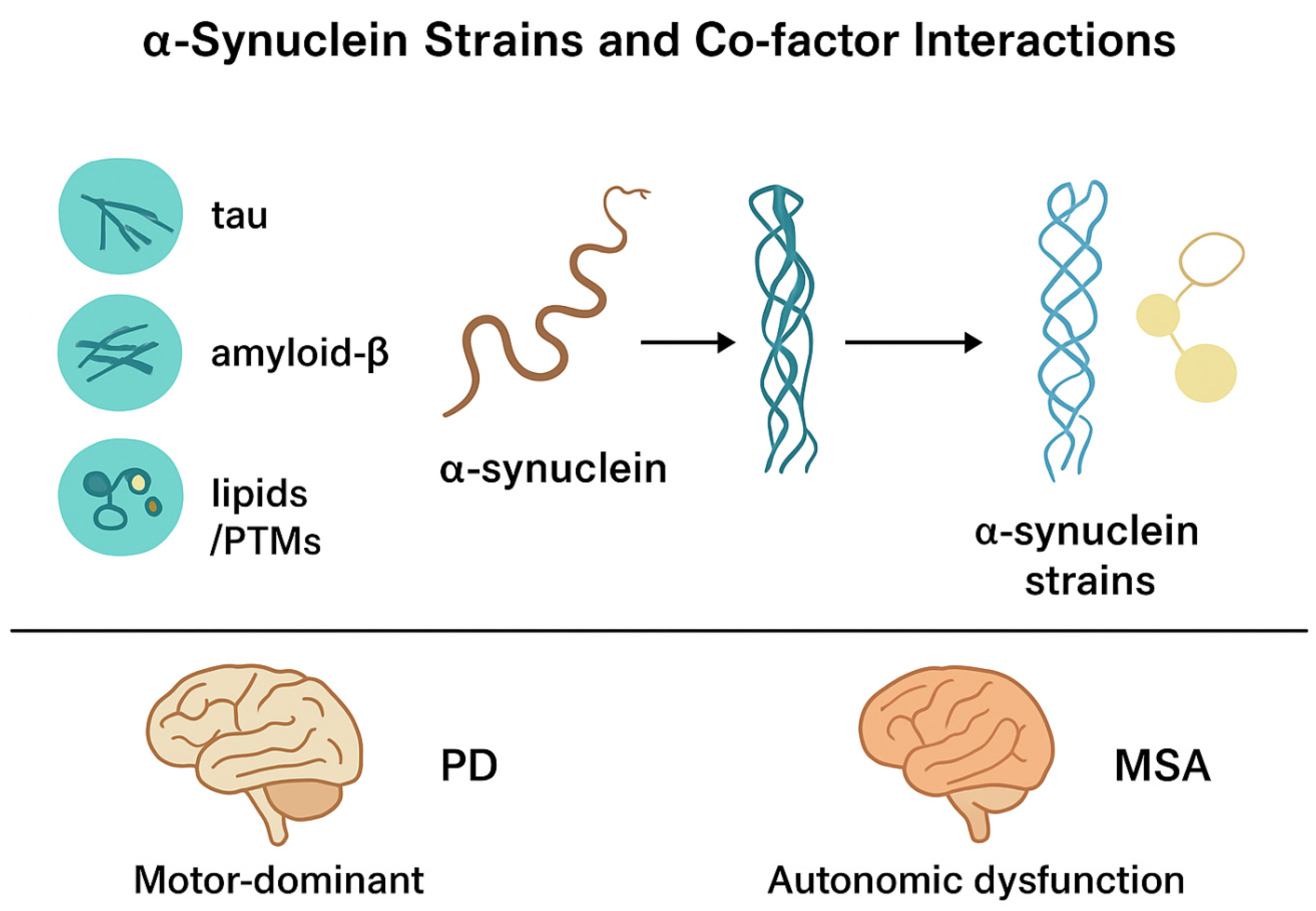

2.4. SNCA Strains in Synucleinopathies

2.5. Mechanisms of Strain Diversity

2.5. Strain Diversity Mechanisms

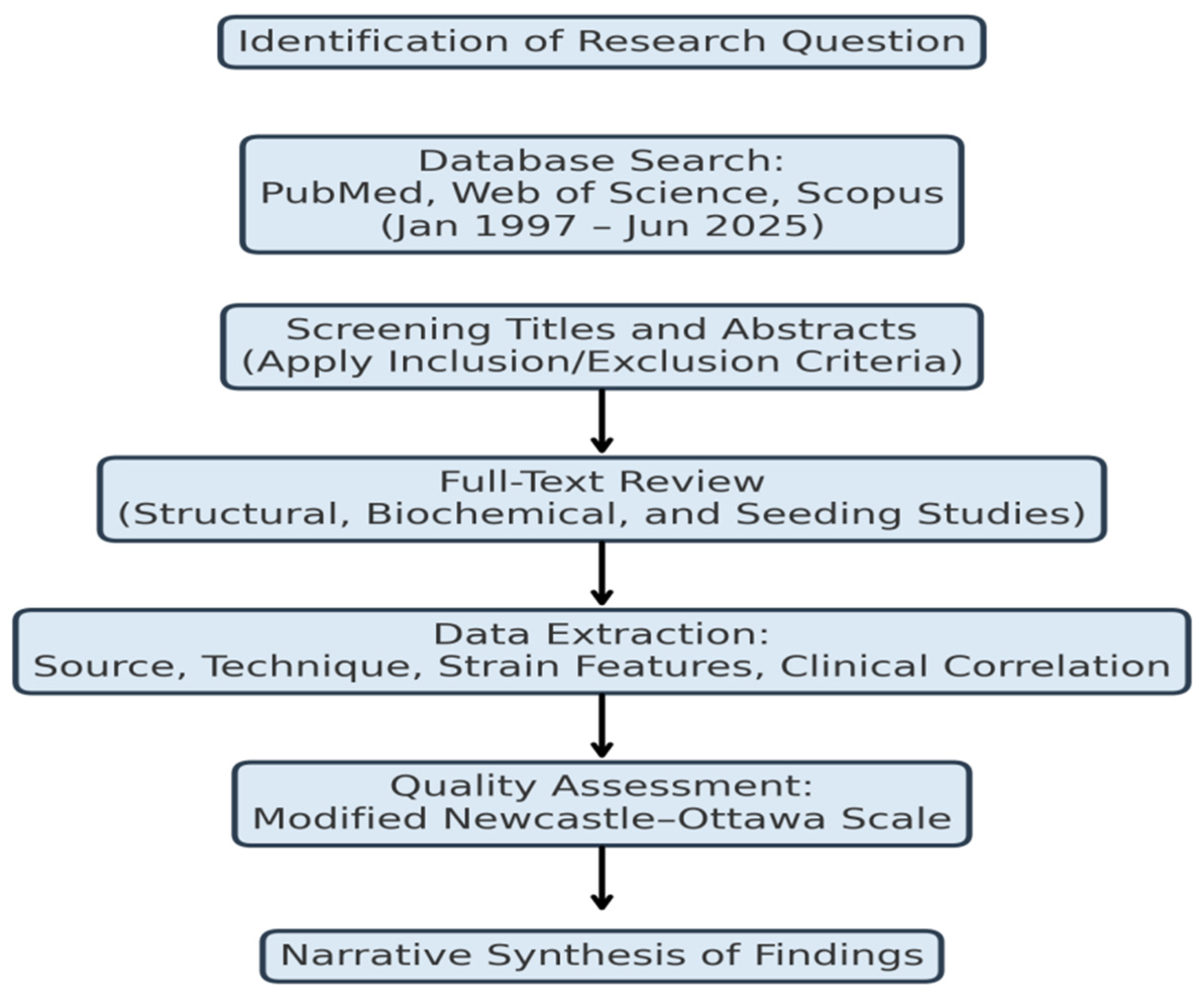

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Literature Search Strategy

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

-

- Original research using human, animal or cell culture models

-

- Studies, demonstrating structural, biochemical, or functional differences between SNCAstrains

-

- Use of advanced detection or amplification methods (cryo-EM, RT-QuIC, PMCA, solid-state NMR)

-

- Data comparing strain characteristics with PD clinical and/or pathological data

-

- Studies addressing only SNCAexpression with aggregation or strain analysis,

-

- Articles that are non-peer-reviewed or conference abstracts without full text,

-

- Reports without primary data (opinion pieces, narrative reviews)

3.4. Data Extraction and Categorization

-

- Origin and type of SNCA aggregate (humans and brain-derived, recombinant fibrils)

-

- Analytical method (structural, biochemical, seeding assay)

-

- Strain-based characteristics (fold morphology, seeding efficiency, cell tropism, stability)

-

- Clinical correspondence (disease type, disease progression, symptomatology)

3.5. Quality Assessment

3.6. Data Synthesis

4. Results

4.1. Structural Diversity of α-Synuclein Strains

4.2. Biochemical and Seeding Properties

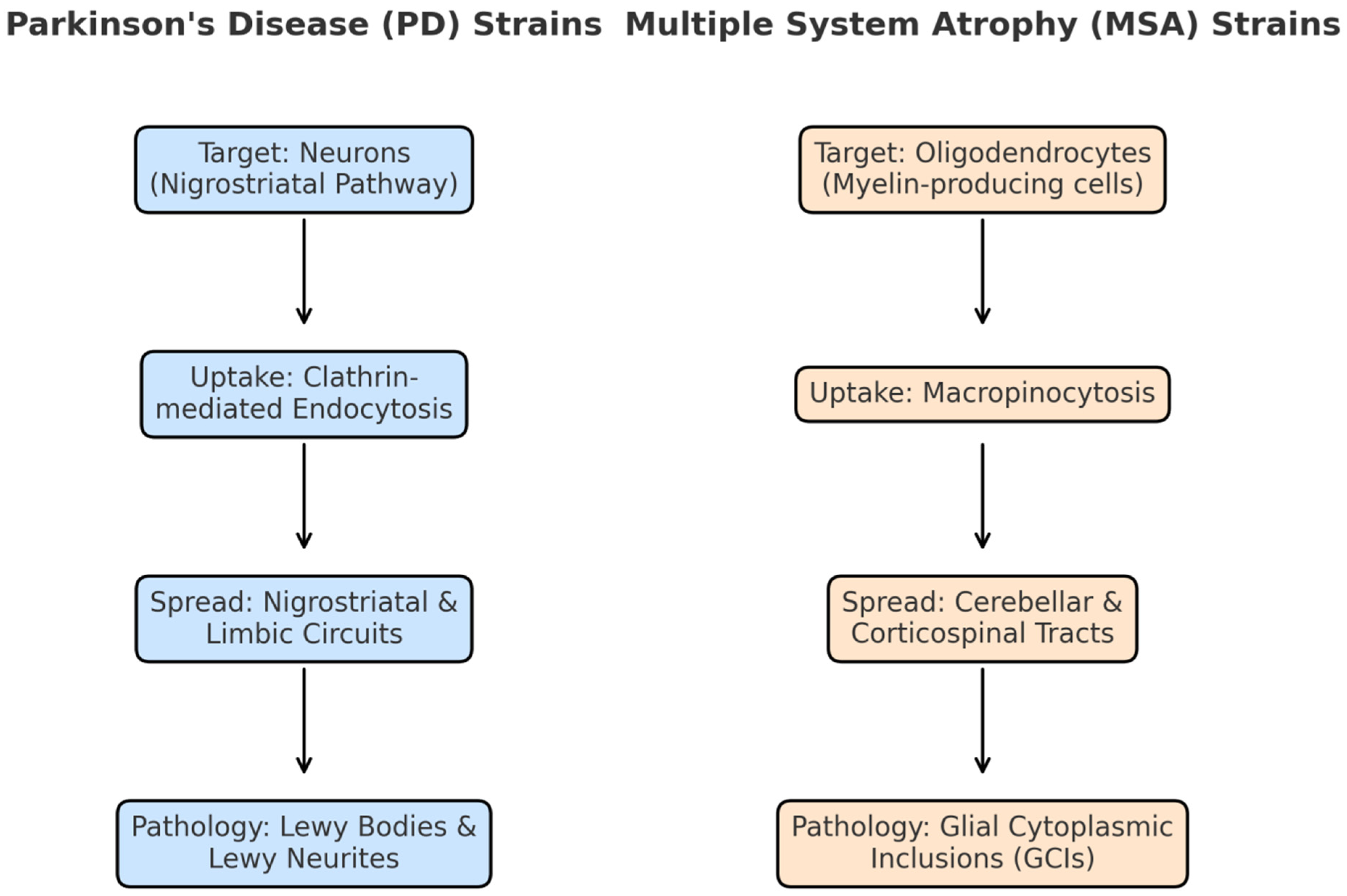

4.3. Cellular Tropism and Pathogenic Spread

4.4. Clinical Correlations

5. Discussion

5.1. Strain-Specific Pathobiology

5.2. Cell-Type Specificity and Neuroanatomical Tropism of α-Synuclein Strains

5.3. Diagnostic Potential and Clinical Translation

5.4. Therapeutic Implications

5.5. Current Gaps and Future Research Priorities

6. Conclusions

References

- Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science (New York, NY). 2010;329(5999):1663-7.

- Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. The many faces of α-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(1):38-48.

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839-40.

- Tiwari PC, Pal R. The potential role of neuroinflammation and transcription factors in Parkinson disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(1):71-80.

- Pal R, Tiwari PC, Nath R, Pant KK. Role of neuroinflammation and latent transcription factors in pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurol Res. 2016;38(12):1111-22.

- Tiwari PC, Chaudhary MJ, Pal R, Kartik S, Nath R. Pharmacological, Biochemical and Immunological Studies on Protective Effect of Mangiferin in 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-Induced Parkinson's Disease in Rats. Ann Neurosci. 2021;28(3-4):137-49.

- Tiwari PC, Chaudhary MJ. Effects of mangiferin and its combination with nNOS inhibitor 7-nitro-indazole (7-NI) in 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesioned Parkinson's disease rats. 2022;36(6):944-55.

- Tiwari PC, Chaudhary MJ, Pal R. Role of Nitric Oxide Modulators in Neuroprotective Effects of Mangiferin in 6-Hydroxydopamine-induced Parkinson's Disease in Rats. 2024;31(3):186-203.

- Awasthi S, Tiwari PC, Awasthi S, Dwivedi A, Srivastava S. Mechanistic role of proteins and peptides in Management of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neuropeptides. 2025;110:102505.

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197-211.

- Surmeier DJ, Obeso JA, Halliday GM. Selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson disease. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2017;18(2):101-13.

- Wong YC, Krainc D. α-synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2017;23(2):1-13.

- Peelaerts W, Bousset L, Van der Perren A, Moskalyuk A, Pulizzi R, Giugliano M, et al. α-Synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature. 2015;522(7556):340-4.

- Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: a neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1988;8(8):2804-15.

- George MS, Wassermann EM, Williams WA, Callahan A, Ketter TA, Basser P, et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. Neuroreport. 1995;6(14):1853-6.

- Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, Lansbury PT, Jr. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35(43):13709-15.

- Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernández-Chacón R, Schlüter OM, Südhof TC. Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell. 2005;123(3):383-96.

- Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, George JM. Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(16):9443-9.

- Fusco G, De Simone A, Gopinath T, Vostrikov V, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, et al. Direct observation of the three regions in α-synuclein that determine its membrane-bound behaviour. Nature Communications. 2014;5(1):3827.

- Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Vedders L, Lue L, White Iii CL, et al. Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta neuropathologica. 2010;119(6):689-702.

- Doppler K. Detection of Dermal Alpha-Synuclein Deposits as a Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2021;11(3):937-47.

- Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, García-Martín E, Santos-García D, Martínez-Valbuena I, Agúndez JAG. Alpha-Synuclein in Peripheral Tissues as a Possible Marker for Neurological Diseases and Other Medical Conditions. Biomolecules. 2023;13(8):1263.

- Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT, Jr. Fibrils formed in vitro from alpha-synuclein and two mutant forms linked to Parkinson's disease are typical amyloid. Biochemistry. 2000;39(10):2552-63.

- Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT. Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant alpha-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 1998;4(11):1318-20.

- Koszła O, Sołek P. Misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases: protein quality control machinery as potential therapeutic clearance pathways. Cell communication and signaling : CCS. 2024;22(1):421.

- Campêlo C, Silva RH. Genetic Variants in SNCA and the Risk of Sporadic Parkinson's Disease and Clinical Outcomes: A Review. 2017;2017:4318416.

- Khalaf O, Fauvet B, Oueslati A, Dikiy I, Mahul-Mellier A-L, Ruggeri FS, et al. The H50Q mutation enhances α-synuclein aggregation, secretion, and toxicity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(32):21856-76.

- Bozi M, Papadimitriou D, Antonellou R, Moraitou M, Maniati M, Vassilatis D, et al. Genetic assessment of familial and early-onset Parkinson's disease in a Greek population. European journal of neurology. 2014;21(7):963-8.

- Krüger R, Kuhn W, Müller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kösel S, et al. AlaSOPro mutation in the gene encoding α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. Nature genetics. 1998;18(2):106-8.

- Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, et al. Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science (New York, NY). 1997;276(5321):2045-7.

- Tanner CM, Kamel F, Ross GW, Hoppin JA, Goldman SM, Korell M, et al. Rotenone, paraquat, and Parkinson's disease. Environmental health perspectives. 2011;119(6):866-72.

- Huang M, Bargues-Carot A, Riaz Z, Wickham H, Zenitsky G. Impact of Environmental Risk Factors on Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Neuroinflammation, Protein Misfolding, and Oxidative Stress in the Etiopathogenesis of Parkinson's Disease. 2022;23(18).

- Jeon YM, Kwon Y, Jo M, Lee S, Kim S, Kim HJ. The Role of Glial Mitochondria in α-Synuclein Toxicity. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2020;8:548283.

- Brás IC, Xylaki M, Outeiro TF. Chapter 4 - Mechanisms of alpha-synuclein toxicity: An update and outlook. In: Björklund A, Cenci MA, editors. Progress in Brain Research. 252: Elsevier; 2020. p. 91-129.

- Patel JC, Shukla M, Shukla M. Cellular and Molecular Interactions in CNS Injury: The Role of Immune Cells and Inflammatory Responses in Damage and Repair. 2025;14(12).

- Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science (New York, NY). 1982;216(4542):136-44.

- Vitting-Seerup K. Most protein domains exist as variants with distinct functions across cells, tissues and diseases. NAR genomics and bioinformatics. 2023;5(3):lqad084.

- Tarutani A, Suzuki G, Shimozawa A, Nonaka T, Akiyama H, Hisanaga S, et al. The Effect of Fragmented Pathogenic α-Synuclein Seeds on Prion-like Propagation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(36):18675-88.

- Kaufman SK, Diamond MI. Prion-like propagation of protein aggregation and related therapeutic strategies. Neurotherapeutics. 2013;10(3):371-82.

- So RWL, Watts JC. α-Synuclein Conformational Strains as Drivers of Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2023;435(12):168011.

- Reddy K, Dieriks BV. Multiple system atrophy: α-Synuclein strains at the neuron-oligodendrocyte crossroad. 2022;17(1):77.

- Tarutani A, Kametani F.

- 43.Merz GE.

- Shahnawaz M, Mukherjee A, Pritzkow S, Mendez N, Rabadia P, Liu X, et al. Discriminating α-synuclein strains in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Nature. 2020;578(7794):273-7.

- Fairfoul G, McGuire LI, Pal S, Ironside JW, Neumann J, Christie S, et al. Alpha-synuclein RT-QuIC in the CSF of patients with alpha-synucleinopathies. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2016;3(10):812-8.

- Fellner L, Jellinger KA, Wenning GK, Haybaeck J. Commentary: Discriminating α-synuclein strains in parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2020;14:802.

- Malfertheiner K, Stefanova N, Heras-Garvin A. The Concept of α-Synuclein Strains and How Different Conformations May Explain Distinct Neurodegenerative Disorders. Frontiers in neurology. 2021;Volume 12 - 2021.

- Reddy K, Dieriks BV. Multiple system atrophy: α-Synuclein strains at the neuron-oligodendrocyte crossroad. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2022;17(1):77.

- Anderson JP, Walker DE, Goldstein JM, de Laat R, Banducci K, Caccavello RJ, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):29739-52.

- Shimogawa M. SITE-SPECIFIC INCORPORATION OF POST-TRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS IN ALPHA-SYNUCLEIN: INSIGHTS INTO AGGREGATION, STRUCTURE, AND FUNCTION: University of Pennsylvania; 2025.

- Schaffert L-N, Carter WG. Do post-translational modifications influence protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. Brain sciences. 2020;10(4):232.

- Miraglia F, Ricci A, Rota L, Colla E. Subcellular localization of alpha-synuclein aggregates and their interaction with membranes. Neural Regeneration Research. 2018;13(7):1136-44.

- Hoppe SO, Uzunoğlu G. α-Synuclein Strains: Does Amyloid Conformation Explain the Heterogeneity of Synucleinopathies? 2021;11(7).

- Peelaerts W, Baekelandt V. ⍺-Synuclein Structural Diversity and the Cellular Environment in ⍺-Synuclein Transmission Models and Humans. 2023;20(1):67-82.

- Bousset L, Pieri L, Ruiz-Arlandis G, Gath J, Jensen PH, Habenstein B, et al. Structural and functional characterization of two alpha-synuclein strains. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2575.

- Guerrero-Ferreira R, Taylor NM. Cryo-EM structure of alpha-synuclein fibrils. 2018;7.

- Brás IC, Dominguez-Meijide A, Gerhardt E, Koss D, Lázaro DF, Santos PI, et al. Synucleinopathies: Where we are and where we need to go. Journal of neurochemistry. 2020;153(4):433-54.

- Dominguez-Meijide A, Vasili E, König A, Cima-Omori M-S, Ibáñez de Opakua A, Leonov A, et al. Effects of pharmacological modulators of α-synuclein and tau aggregation and internalization. Scientific reports. 2020;10(1):12827.

- Galvagnion C. The Role of Lipids Interacting with α-Synuclein in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson's Disease. Journal of Parkinson's disease. 2017;7(3):433-50.

- Sanderson JM. The association of lipids with amyloid fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(8):102108.

- Villar-Piqué A, Lopes da Fonseca T, Outeiro TF. Structure, function and toxicity of alpha-synuclein: the Bermuda triangle in synucleinopathies. Journal of neurochemistry. 2016;139 Suppl 1:240-55.

- Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, et al. alpha-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(2):160-4.

- Dufty BM, Warner LR, Hou ST, Jiang SX, Gomez-Isla T, Leenhouts KM, et al. Calpain-cleavage of alpha-synuclein: connecting proteolytic processing to disease-linked aggregation. The American journal of pathology. 2007;170(5):1725-38.

- Zhang S, Lingor P. Strain-dependent alpha-synuclein spreading in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. 2024;19(12):2581-2.

- Anderson JC, Clarke EJ, Arkin AP, Voigt CA. Environmentally controlled invasion of cancer cells by engineered bacteria. J Mol Biol. 2006;355(4):619-27.

- Srinivasan E, Chandrasekhar G, Chandrasekar P, Anbarasu K, Vickram AS, Karunakaran R, et al. Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation in Parkinson's Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:736978.

- Pieri F, Aldini NN, Fini M, Marchetti C, Corinaldesi G. Immediate fixed implant rehabilitation of the atrophic edentulous maxilla after bilateral sinus floor augmentation: a 12-month pilot study. Clinical implant dentistry and related research. 2012;14 Suppl 1:e67-82.

- Walker L, Attems J. Prevalence of Concomitant Pathologies in Parkinson's Disease: Implications for Prognosis, Diagnosis, and Insights into Common Pathogenic Mechanisms. Journal of Parkinson's disease. 2024;14(1):35-52.

- Yang Y, Garringer HJ, Shi Y, Lövestam S, Peak-Chew S, Zhang X, et al. New SNCA mutation and structures of α-synuclein filaments from juvenile-onset synucleinopathy. Acta neuropathologica. 2023;145(5):561-72.

- Schweighauser M, Shi Y. Structures of α-synuclein filaments from multiple system atrophy. 2020;585(7825):464-9.

| Year | Author(s) | Model/Method | Key Findings | Clinical Relevance |

| 1997 | Polymeropoulos et al. | Genetic linkage study | Identified A53T mutation in SNCA | Established genetic cause of familial PD |

| 2001 | Conway et al. | In vitro fibrillization | Demonstrated spontaneous SNCAaggregation | Basis for aggregation assays |

| 2013 | Guo et al. | Cell culture, seeding | Demonstrated prion-like propagation of α-syn | Introduced strain concept to α-syn |

| 2015 | Peelaerts et al. | Mouse models | Different SNCAstrains produce distinct pathologies | Explained heterogeneity in synucleinopathies |

| 2016 | Fairfoul et al. | RT-QuIC assay | Discriminated PD vs MSA SNCAin CSF | Potential diagnostic biomarker |

| 2018 | Li et al. | Cryo-EM | Resolved PD vs MSA fibril structures | Structural basis for strain differences |

| 2020 | Shahnawaz et al. | PMCA assay | MSA seeds amplify more efficiently than PD seeds | Supports clinical progression differences |

| Parameter | Example Categories |

| Source of α-syn | PD brain tissue, MSA brain tissue, recombinant protein |

| Analytical technique | Cryo-EM, solid-state NMR, RT-QuIC, PMCA |

| Strain-specific features | Fibril twist pitch, thermodynamic stability, protease resistance |

| Clinical correlation | PD slow progression, PD rapid progression, MSA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).