1. Introduction

The links between human papillomavirus (HPVs) and cervical cancer were first demonstrated almost 50 years ago. [

1]. Currently advanced biotechnological approaches have improved the knowledge of host-virus interplay highlighting the key role of host immune response, microbiome homeostasis and coinfection with sexually transmitted pathogens. Moreover, technologies such as liquid biopsies, DNA methylation triage and detection of HPV integration, have implemented traditional screening methods [

2].

HPV is a DNA tumor virus belonging to the Papillomaviridae family and today, more than 200 genotypes have already been characterized and sequenced [

3,

4]. Each genotype of HPV acts as an independent infection, with differing carcinogenic risks. HPV subtypes can be categorized into Low Risk (LR) variants, which encompass types 6, 11, 4, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, associated with benign lesions including genital, anal, oral, or throat warts and into High Risk (HR) variants consist of types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82 where HPV16 and 18 cause the majority of HPV related cancers including cervical, anogenital and head-neck cancers [

3,

4]. The clinical signs were strongly related to host immune response. Basically, while LR-HPV infections resolve spontaneously in a couple of years, HR-HPV establishes a persistent infection that overcome the immune system’s defenses forming precancerous lesions that can progress to cancer over time [

3,

4].

HPV infection is considered one of the most common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide with significant implications for public health. [

5]. Epidemiological data report that 80% of sexually active individuals will be infected by HPV during their lifetime. Age-specific analysis revealed a high prevalence of HPV peaks in adolescence and among young population under 25 years old after first sexual activity [

4,

6]. Young men over the age of 15 years reported a high prevalence of infection [

4,

6] representing an important and often silent reservoir for viral transmission. HPV prevention acts to target the population through proactive intervention strategies including screening, vaccination, information campaigns, education and awareness about HPV and STIs coinfections implicated in HPV transmission and clinical progression [

7].

HPV vaccine is offered to adolescent between 9 and 14 years of age, or in three doses to individuals aged 15 years or older [

8] and, in some countries, this schedule has been adopted for both males and females since 2018 [

9]. Although many countries have introduced a national program [

10], the overall coverage is still not optimal. Vaccine safety concerns and a lack of HPV knowledge still represent the main barriers, especially for males. To overcome this cultural gap, efforts about educational programs are recently proposed to schools that represent the best place to introduce a pedagogical approach for sex education, prevention and social responsibility [

6]. The aim of this review is to explore the actual global magnitude of HPV impact on public health system with particular attention to adolescents and focus on the emerging potential alternatives for HPV prevention and diagnosis.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was conducted to summarize current evidence on human papillomavirus (HPV) epidemiology, clinical manifestations, prevention strategies, and future perspectives, with a particular focus on adolescents. A non-systematic literature search was performed in the main biomedical databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science) for publications in English up to August 2025. Search terms included combinations of “human papillomavirus”, “HPV epidemiology”, “HPV vaccine,” “screening,” “microbiome,” “sexually transmitted infections,” and “therapeutic vaccine.” Additional references were identified from the bibliographies of relevant articles and official reports from international health agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Given the narrative nature of this work, no predefined protocol or systematic review methodology (e.g., PRISMA) was applied. Selection of articles was based on relevance, originality, and contribution to the understanding of HPV infection and prevention. Both original research and review articles were considered, along with recent epidemiological reports and policy documents. Particular attention was given to studies addressing HPV burden in adolescents, vaccine acceptance, and innovative diagnostic or preventive strategies. The evidence was synthesized to provide an integrated and updated overview, aiming to highlight knowledge gaps and future research directions.

3. Epidemiology

According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) data, HPV infection contributes to 5% of all cancers worldwide each year, with approximately 626,000 women and 69,400 men diagnosed with HPV-related cancers. Infection with HR-HPV, particularly HPV types 16 and 18, accounts for about 70% of cervical cancers globally. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide, with an estimated 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths in 2022. In response to these data, the WHO launched a global strategy in 2020 to address cervical cancer as a public health issue. The strategy aims for 90% of girls to be fully vaccinated with the HPV vaccine by age 15, 70% of women to undergo screening by the ages of 35 and 45, and 90% of women diagnosed with cervical disease to receive appropriate treatment (90% of women with precancerous conditions treated and 90% of women with invasive cancer treated) [

11].

The cervix was the most affected site (46%), followed by the anus (20%), vulva (17%), oropharynx (14%), and vagina (3%). Mortality data from Europe shows nearly 26,000 deaths in 2020, making cervical cancer the tenth leading cause of death in women and the third most common cause of death in women aged 15–44 [

12]. Global pooled prevalence for genital HPV infection among men was 31% for any HPV and 21% for HR-HPV where HPV-16 is the most common HPV oncogenic and preventable type. HPV prevalence in men peaked in the group aged 25–29 years and remained high until at least age 50 years. Prevalence in the group aged 15–19 years was also high, suggesting that young men are being infected rapidly following first sexual activity. The age profile of infection in women is different from that of men, showing a prevalence peaks soon after first sexual activity that decline with age, and a slight rebound after age 50–55 years. Among extragenital HPV-related cancer, the most of them occurred in the oropharynx (82%) [

6].

4. Clinical Manifestations and Co-Infection with STI

HPV pathogenesis begins in the host cell, where HPV releases its viral genome which is endocytosed in the nucleus of the same cell to replicate its DNA in synchrony and to express viral genes [

3,

4]. Translated genes are mainly those encoding the oncoprotein E6 and E7 which are linked to viral pathogenic activity and are crucial for the transformation of infected cells as they are involved in the regulation of the host cells cycle [

3,

4]. The clinical manifestations range from minor issues such as warts to serious conditions like tumors. Anogenital warts are typically asymptomatic, although their size and anatomical location can cause discomfort or pruritus [

3].

The vast majority of anogenital warts, approximately 90%, are caused by non-oncogenic HPV types 6 or 11. They are typically flat, papular, or pedunculated growths that commonly manifest in specific anatomical locations, including the vaginal introitus, the foreskin of the penis, the cervix, the vagina, the urethra, the perineum, the perianal skin, the anus, and the scrotum. In rare cases, oncogenic HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35 can also be identified in these lesions [

13]. A rare but highly disabling disease is the recurrent respiratory papillomatosis affecting the upper aerodigestive tract of both children and young adults.

Papillomavirus typically presents as exophytic nodules, predominantly in the larynx, although they may also occur in the nasopharynx, tracheobronchial tree, and lung parenchyma. In some cases, lesions may resolve spontaneously. However, in rare instances, there is a potential for the lesion to evolve into squamous cells carcinoma. In clinical practice, recurrent respiratory papillomatosis typically presents with nonspecific symptoms indicative of airway involvement, including chronic cough, hoarseness, wheezing, voice changes, stridor, and chronic dyspnea [

14,

15,

16]. In some instances, these lesions resolve spontaneously while in other cases, surgical intervention is recommended to prevent disease progression [

17].

In a small proportion of women, the virus can establish a persistent infection, probably due to the synergistic effect of a suboptimal host-dependent immune response which may initiate the process of carcinogenesis. Genotypes 16 and 18 are primarily associated with the development of carcinomas in the cervix, the anogenital region (vulva, vagina, penis, and anus), and the head and neck (mouth, tonsils, pharynx, and larynx) [

18,

19]. The most common type of cancer due to a persistent HR-HPV infection is cervical cancer and, along with other risk factors, it can lead to low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (L-SIL), which include mild dysplasia known as CIN 1 (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1). This can then progress to high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (H-SIL). H-SIL is a progressive lesion that can evolve into moderate dysplasia (CIN 2) and then severe dysplasia (CIN 3) [

20,

21,

22,

23]. The most clinically encountered cervical tumors are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

Recent studies have shown that the presence of cervical lesions related to HPV infection increases the risk of acquiring other STI infections. It was reported that in women, persistent HPV infection raises the likelihood of contracting HIV, [

24] and at the same time, an HIV-positive has a higher risk of acquiring HPV infection, especially due to high-risk types [

3,

25]. The co-infection with persistent high-risk HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) has been suggested as a contributing factor to the advancement of cervical cancer in women. The ability of CT in activating a chronic inflammation and to produce damage to epithelial integrity, played a key role to support persistence of HPV infection and cells transformation [

24,

26]. Moreover, recent studies revealed the role of Escherichia coli infecting HPV-16 cervical lesions that seems to cooperate in the severity of disease [

27].

5. Extragenital HPV Associated-Cancers

Although genital cancers are in both gender the most common and frequent disease associated with HPV infection, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) incidence has increased more rapidly in recent years particularly in Europe and the United States [

28,

29]. HNSCC refers to a class of squamous cell carcinoma that arises in the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck region, which can develop in various sites of upper aerodigestive tract, including the oral cavity: oropharynx, larynx and hypopharynx [

3,

30].

Although the alcohol and tobacco abuse is found as the main risk factor in the onset of tumors in the upper sites of the aerodigestive tract, [

31], a high proportion of these cancers especially in the oropharyngeal portion, can be attributed to HPV infection [

3,

30,

31] mainly to HPV-16, with a higher prevalence in men than in women [

3,

30].

However, an important aspect can be observed when comparing patients with HPV-related HNSCC and patients with the same disorder not related to infection. Patients with non-HPV-related HNSCC show a less favorable prognosis and a lower response to treatment compared to those positive for HPV [

3,

30]. Although it is clear that HPV positivity plays a key role in the development of HNSCC, the biological behavior of these tumors differs depending on the site of infection.

6. Testing and Screening

Specific diagnosis and screening programs are two essential tools in the management of HPV infections. The primary diagnostic tools have been cytology (Pap-Test) and histology, along with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), which are currently the most common method for detecting HPV and are considered the gold standard [

32]. NAATs can detect the presence of HPV DNA or messenger RNA (mRNA geno hpv) in a variety of samples, including cervical swabs, anal and buccal swabs, or saliva. PCR-based tests are widely used due to their high sensitivity, specificity, and ability to detect multiple HPV genotypes simultaneously [

30,

33,

34].

The most common routine for cervical cancer screening is based on the Pap-test and the HPV-DNA test. A Pap test looks for precancerous cell changes on the cervix that might develop into cervical cancer if not treated appropriately, while an HPV test looks for the HPV virus, which can cause cell changes on the cervix [

34]. Current guidelines recommend that women between the ages of 25 and 30 should be tested with cervical cytology alone (Pap test), and screening should be performed every 3 years. The HPV-DNA test is offered to women between the ages of 30 and 64 every 5 years if the result is negative. There is no approved screening test for HPV in men, but HPV testing may be required for men who are at high risk of infection, such as those who are immunocompromised or those who have sex with other men [

35]. Despite WHO recommendations in terms of prevention, only one-third of women aged 30-49 have been screened at least once in their lifetime. This percentage varies across global regions, with the percentage of access to treatment and prevention options below 10% in low-income and lower-middle-income countries which also accounted for the highest burden of disease [

36].

The most recent studies in terms of screening are focused on developing alternative techniques to PCR-based tests, but with the same sensitivity and specificity. This is to achieve a reduction in terms of costs, equipment, and highly specialized personnel to increase screening coverage even in the poorest areas of the world [

34]. One of these approaches, is called isothermal amplification techniques (IATs), that operate at constant temperature and are often shorter than PCR. The most engaged IAT is a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), which provides for the use of Bst polymerase and a group of four to six primers to rapidly amplify either DNA or RNA, a common approach to study bacterial and viral nucleic acid [

30,

34]. Therefore, Lamp could be a good choice for fast determination of HPV infection, but it is highly sensitive to contamination and primers need to be created with a special software and to be tested before using them [

30,

34]. According to the need for a quick, simple, and cost-effectiveness technique, we can transfer the attention on the research of specific HPV-DNA with reverse dot/line blot or on the protein detection through lateral flow assay (LFA). The first method provides the hybridization of gene specific oligonucleotide probes, coated on a predefined dot or line, with complementary target DNA, allowing the contemporary identification of more HPV types together. Instead, the second one, LFA, is based on a paper analytic platform to detect the presence or the absence of target analytes, which are released based on the principle of an ELISA. If the analyte is present, it binds to a labeled antibody and this complex moves along the strip to detection zone where it is recognized by immobilized antibodies or antigens in the test or control line; if there is no analyte, the line does not appear.

This technique could be coupled with PCR or IAT amplification and this combined approach has been used to detect genomic DNA of different HPV genotypes [

34]. The last approach is focused on the innovative CRISPR-Cas-based system and the implementation of Cas12a which targets a specific gene of HPV helping the recognition of HPV-16 and 18 in a variety of clinical samples, such as plasma and anal swabs. CRISPR-Cas system has a great sensitivity and specificity with a relatively inexpensive manner, but it requires a lot of precision in the design of guide RNAs [

30,

34]. The final goal of research into new HPV screening techniques will be the development of point-of-care tests to enable increasingly simple and rapid diagnosis, even in areas of the world with fewer economic and healthcare resources [

34,

37]. Not only the techniques in the field are considered for the improvement of screening programs, but also the procedure of test sample collection and its type.

To perform screening tests, the collection of samples can be made as self-sampling [

30,

37]. Self-sampling is a safe and simple approach which can increase screening rates due to better privacy and personal comfort compared to traditional sampling [

30,

37]. Moreover, self-sampling enables greater screening coverage, especially in low-resource areas where infrastructure and healthcare workforce are very limited. Indeed, thanks to this evidence, in 2021 the WHO included self-sampling in its guidelines for cervical cancer screening, and it has already been introduced as a sample collection protocol in 35% of the 139 countries that have an official screening recommendation plan [

36,

38,

39]. In addition, DNA methylation technology is a molecular triage test providing accurate results across settings without comprehensive cervical cancer screening programs.

The methylation test could be used for primary screening, referring HPV-positive/methylation positive women to immediate treatment and negative women to follow-up after an appropriate number of years using a single sample [

40]. Recent research focused to seek new biomarkers for early diagnosis or prognostic outcome in patients with HPV mediated cancer. In this context, a recent study showed as the presence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the blood could be a possible robust biomarker using digital polymerase chain reaction or NGS technology. Chennareddy et all (2025) highlight the role of ctDNA to monitor the treatment response. It was reported that both tumor resection and chemotherapy were responsible for a decrease in ctDNA levels and its complete clearance at the end of the chemotherapy cycle is associated with a higher chance of recovery [

41].

7. Prevention

Currently, there is no established therapeutic intervention for individuals infected with HPV, but various therapeutic protocols are available for clinical management [

39,

42]. The prophylactic use of vaccines against HPV to prevent the development of cancer has proven to be an effective method. HPV vaccines are based on the L1 capsid protein, which assembles into virus-like particles (VLPs). These VLPs induce antibodies that neutralize specific HPV types and are antigenically identical to HPV virions, enabling effective immune responses [

43]. The comprehension of HPV-induced carcinogenesis, together with the accessibility of VLPs, has facilitated the creation of numerous prophylactic vaccines against HPV, which are summarized in

Table 1. Gardasil® (Merck, Sharp & Dome (Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) is a quadrivalent vaccine targeting HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, and HPV-18. It provides protection against genital warts caused by HPV-6 and HPV-11 and high-risk HPV types linked to cervical cancer. Cervarix® (GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium) a bivalent vaccine targeting HPV-16 and HPV-1. Clinical trials have demonstrated its efficacy against high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN3) and a strong safety profile [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Gardasil 9 ® (Merck, Sharp & Dome (Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA)) a nonavalent vaccine licensed in 2014 that targets HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52 and HPV-58 [

49,

50]. Cecolin® (Xiamen Innovax Biotechnology, Xiamen, China), a bivalent vaccine using Escherichia coli to produce HPV-16 and HPV-18 L1 VLPs [24161937]. Cecolin® was pre-qualified by the WHO in 2021. Recently a recombinant bivalent HPV vaccine (Shanghai Zerun Biotechnology, a subsidiary of Walvax Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) targeting HPV-16 and HPV-18 has been pre-qualified by the WHO for use in 2022 [

51].

Following the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) directives many European countries had introduced HPV vaccination for females and some of them had organized catch-up programs. Recently, HPV program has been extended to males and implemented in gender-neutral vaccination [

53,

54]. Each vaccine provides specific protection against targeted subtypes and demonstrates some degree of cross-protection against non-vaccine HPV subtypes [

55]. Vaccination induces significantly higher antibody titers against specific HPV types than those observed in individuals naturally infected. Notably, individuals vaccinated before the age of 16 exhibit higher antibody titers than older adolescents and adults [

56] and this reflects the importance of vaccine administration before the onset of sexual activity to maximize the effect of vaccine protection, which is easier to achieve when people have not yet been exposed to HPV infections [

3]. Recent data indicate an increase in single-dose HPV vaccine coverage among girls aged 9-14 years, rising from 20% in 2022 to 27% in 2023 [

56].Due to the possibility of accurate screening programs the cervical cancer elimination strategy established by the WHO, provides coverage targets for scale-up by 2030 to 90% of all adolescent girls, twice-lifetime cervical screening to 70% and treatment of pre-invasive lesions and invasive cancer to 90% [

57].

8. Educational Programs

To improve vaccination coverage and move closer to the goals given by WHO for 2030, it is crucial to implement education programs starting from adolescents in terms of sex education, knowledge about HPV and STIs and prevention strategies including the importance of vaccination [

5,

58,

59]. In terms of education, the school remains the ideal place to implement training programs thus enabling better interaction with health services [

60]. On this issue, in 2024, Brunelli et all published recently an innovative multidisciplinary model taking place in the upper and secondary schools.

The proposed training program was supported by a team of experts who train identified volunteers in schools to conduct permanent peer meetings about STIs and HPV to raise awareness of sexual and reproductive health issues, including vaccination, to implement the effectiveness of the training among students, while adults (parents and teachers) will participate in distance and face-to-face trainings [

58]. Two interesting aspects emerged recently concern adolescent self-awareness and gender-neutral vaccination [

60]. In many states parental consent is needed to vaccinate adolescents, who cannot intervene in choices for their own health. For this reason, it is referred to as self-consent, which must be preceded however, by appropriate education to enable adolescents to make concealed health choices [

5,

10,

61]. In addition, the possibility of having training programs in schools highlight the disparity between males and females in the opportunity to receive HPV vaccine introducing the concept of gender-neutral vaccination. Only a minority of countries with an HPV vaccine program included males in vaccine administration [

10]. Italy was the first European country to introduce universal vaccination for both males and females in 2017 [

58].

Vaccination campaigns were designed only for girls because of the major side effects that HPV infection can give them, first and foremost cervical cancer and that they would also reflexively protect boys through herd immunity if vaccination coverage in females is high enough [

10,

62,

63]. Unfortunately, the effect of herd immunity is currently not achievable given the low overall vaccination rate, and it was suggested that it is more cost-effective to increase the level of coverage in girls than to offer the vaccine to boys as well [

10]. To note, men are also susceptible to HPV oncogenic infections that usually can progress to anal and penile cancers, demonstrating the undeniable importance of adherence of vaccine program as prevention strategy for boys as well.

9. Future Directions

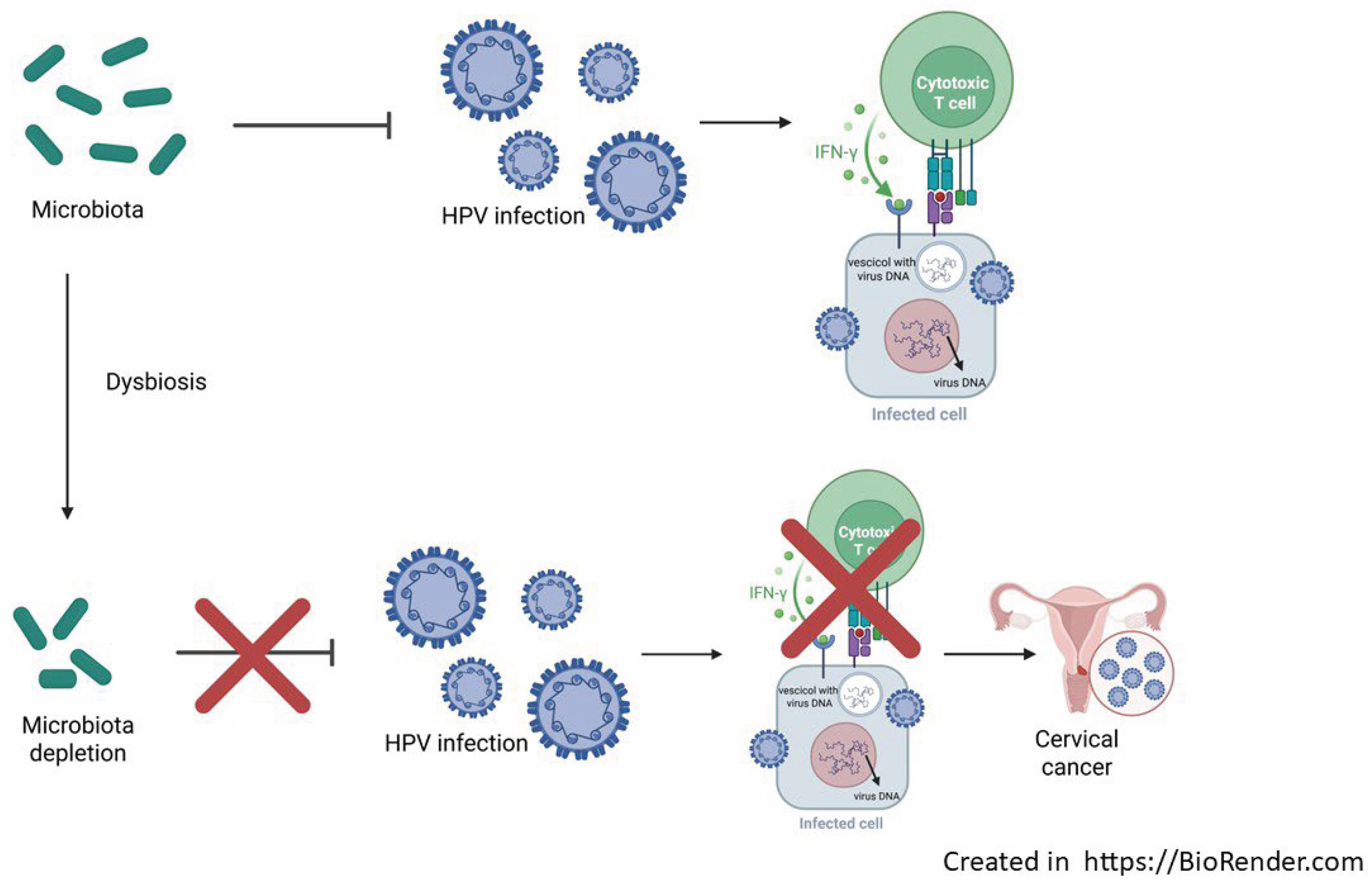

9.1. Microbiome

The next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology and bioinformatics has allowed to unveil the inter-play between human microbiota and HPV in term of infection, establishment, persistence and disease progression. Basically, it has been demonstrated that bacterial species composition can modulate the susceptibility of infections, patients’ outcomes, and more interesting the host immune response to infection [

64]. The vaginal dysbiosis represents a dysregulated and functionally impaired microbiome that tends to promote chronic low-grade inflammation, immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, DNA damage and metabolic rewiring. In addition to dysbiosis, the host response, including cellular and cytokine markers of inflammation, increased susceptibility for STIs, HR-HPV and progression to cervical carcinogenesis [

65] (

Figure 1).

It’s proven that vaginal microbiota can be modulated to restore local homeostasis and to promote beneficial effects to host through the HPV clearance and cytological abnormalities [

67,

68]. In this context Lactobacilli are the most commonly probiotics for microbiota modulation acting to prevent pathogens infections through bacterial competition and to release of inhibitory factors [

69,

70]. At the same time, enhanced immune response and reduction of inflammation were observed [

71] suggesting its possible future application in term of personalized medicine.

9.2. Therapeutic Vaccine

In order to target HR-HPV infection, mucosal vaccine has been proposed due to its characteristics of non-invasiveness and of a lower technical requirement. The latest generation of mucosal live vaccines is based on transgenic technology to modify live bacteria and probiotics enabling them to produce and deliver preventive and therapeutic antigens [

72,

73]. The Gram positive Lactococcus lactis, is considered a promising vaccine vector due to its relative safety, lack of endotoxic lipopolysaccharides, and cost-effectiveness [

74]. The expression of some protein can also serve as an antigen delivery carrier to activate the host immune system. This vaccine can directly target the mucosa in the reproductive tract to deliver antigens and induce a local protective immune response [

75]. The engineered BLS-M07 drug, expressing the HPV-16 E7 antigen as a target on the surface of L. casei, is orally administered. Park et al. conducted Phase I and IIa clinical trials to evaluate its efficacy and safety in CIN3 patients. HPV E7 protein on the surface of Lactobacillus was recognized by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and activated cytotoxic T cells [

76]. These data showed a significant increase in serum HPV-16 E7-specific antibodies (75 %) and no patients experiencing treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or above throughout the study [

76].

10. Discussion and Conclusions

HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptance vary across different countries. Safety concerns are still the main barrier to vaccination, and lack of HPV, vaccine knowledge and social responsibility has been identified, especially in males [

77]. Moreover, the idea that HPV vaccination may encourage sexual activity is widespread among the general population. HPV vaccination coverage rates and parental acceptance are still a subject of debate, although several initiatives have been recently implemented by experts with particular attention to adolescent and young population, based on multidisciplinary tools including educational, parental, scientific, and political resources. Nevertheless, HPV vaccine acceptance varies by target population’ characteristics where socioeconomic background represents a key bias. The need for “tailored” interventions, designed to respond to personal, epidemiological and local public health concerns would be offered to the target population to reduce social inequalities and thus decrease the impact on health governance. In addition, strategies of interventions oriented to adolescent seem to be more effective. In this sense public health interventions with the additional components of education, social tools and remained-based strategies appeared to be positively accepted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.; methodology, V.B., and N.W.; resources, M.C.; data curation, V.B., N.W., D.G., A.C., T.M.A.F., G.CAP., F.S., F.V., writing—original draft preparation, V.B., M.C., writing—review and editing, N.Z., C.C., G. CAM., supervision, M.C.S., B.S., L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was carried out with the technical and financial support of the Italian Ministry of Health—CCM (study project ESPRIT—Education in lower and upper secondary school and support of the network of adolescent reference persons for the prevention of HPV and other sexually transmitted infections), and through the contribution given to the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy (research project SD 13/18).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- zur Hausen, H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: From basic studies to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Cao, C.; Wu, P.; Huang, X.; Ma, D. Advances in cervical cancer: current insights and future directions. Cancer Commun. 2024, 45, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Kist, L.F.; Pereira, S.B.; Quessada, M.A.; Petek, H.; Pille, A.; Maccari, J.G.; Mutlaq, M.P.; Nasi, L.A. Human papillomavirus infection: Epidemiology, biology, host interactions, cancer development, prevention, and therapeutics. Rev. Med Virol. 2024, 34, e2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.; Yadav, D.; Jarouliya, U.; Chavda, V.; Yadav, A.K.; Chaurasia, B.; Song, M. Epidemiology, Molecular Pathogenesis, Immuno-Pathogenesis, Immune Escape Mechanisms and Vaccine Evaluation for HPV-Associated Carcinogenesis. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzetta, S.; Valent, F.; Sala, A.; Driul, L.; Brunelli, L. Sexually transmitted infections and the HPV-related burden: evolution of Italian epidemiology and policy. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1336250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Rowley, J.; Alemany, L.; Arbyn, M.; Giuliano, A.R.; E Markowitz, L.; Broutet, N.; Taylor, M. Global and regional estimates of genital human papillomavirus prevalence among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2023, 11, e1345–e1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Milani, A.; Seyedinkhorasani, M.; Bolhassani, A. HPV co-infections with other pathogens in cancer development: A comprehensive review. J. Med Virol. 2023, 95, e29236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2021. Human Papillomavirus Infection: recommended vaccinations. https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByDisease?SelectedDiseaseId=38&SelectedCountryIdByDisease=-1” 28 August 2025.

- Italian Ministry of Health, 2015. National Vaccination Prevention Plan 2016-2018.

- Sundaram, N.; Voo, T.C.; Tam, C.C. Adolescent HPV vaccination: empowerment, equity and ethics. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 16, 1835–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, G. W. H. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. 2020.

- Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado JJ, M. J. Gómez D, Bosch FX and d. S. S. Ico/iarc information centre on hpv and cancer (hpv information centre). Human papillomavirus and related diseases in europe. Summary Report. 10 March 2023.

- Dediol, I.; Buljan, M.; Vurnek-Živković, M.; Bulat, V.; Šitum, M.; Čubrilović, Ž. Psychological burden of anogenital warts. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, H.R.; von Ranke, F.M.; Escuissato, D.L.; Neto, C.A.A.; Zanetti, G.; Hochhegger, B.; Souza, C.A.; Marchiori, E. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: A state-of-the-art review. Respir. Med. 2017, 126, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcier, M.; Bhatia, N.; Lynde, C.; Vender, R. Managing external genital warts: practical aspects of treatment and prevention. . 2013, S68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Workowski, K.A.; Bolan, G.A.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR. Recomm. Rep. 2015, 64, 1–137. [Google Scholar]

- El Moussaoui, S.; Fernández-Campos, F.; Alonso, C.; Limón, D.; Halbaut, L.; Garduño-Ramirez, M.L.; Calpena, A.C.; Mallandrich, M. Topical Mucoadhesive Alginate-Based Hydrogel Loading Ketorolac for Pain Management after Pharmacotherapy, Ablation, or Surgical Removal in Condyloma Acuminata. Gels 2021, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araldi, R.P.; Sant’Ana, T.A.; Módolo, D.G.; de Melo, T.C.; Spadacci-Morena, D.D.; de Cassia Stocco, R.; Cerutti, J.M.; de Souza, E.B. The human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancer biology: An overview. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1537–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; Pérez-Maya, A.A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, H.F.; Gómez-Macias, G.S.; Fajardo-Ramírez, O.R.; Treviño, V.; Barrera-Saldaña, H.A.; Garza-Rodríguez, M.L. Understanding the HPV integration and its progression to cervical cancer. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 61, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bañuelos-Villegas, E.G.; Pérez-Ypérez, M.F.; Alvarez-Salas, L.M. Cervical Cancer, Papillomavirus, and miRNA Dysfunction. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 758337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliopoulos, G.; Nyaga, V.N.; Santesso, N.; Bryant, A.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Mustafa, R.A.; Schünemann, H.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Arbyn, M. Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD008587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, J.; Bossart, M.; Bamberg, F.; Eisenblaetter, M. Revised FIGO Staging for Cervical Cancer – A New Role for MRI. Rofo-Fortschritte Auf Dem Geb. Der Rontgenstrahlen Und Der Bild. Verfahr. 2020, 192, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorelli, S.; Odicino, F. Cervical Cancer Staging. Cancer J. 2003, 9, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Mugo, N.R.; Brown, E.R.; Mgodi, N.M.; Chirenje, Z.M.; Marrazzo, J.M.; Winer, R.L.; Mansoor, L.; Palanee-Phillips, T.; Siva, S.S.; et al. Prevalent human papillomavirus infection increases the risk of HIV acquisition in African women: advancing the argument for human papillomavirus immunization. AIDS 2021, 36, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, A.; Cachay, E.; Ocampo, A.; Poveda, E. Update on the Epidemiological Features and Clinical Implications of Human Papillomavirus Infection (HPV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Coinfection. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bhor, V.M. A literature review on correlation between HPV coinfection with C. trachomatis and cervical neoplasia - coinfection mediated cellular transformation. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 168, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Su, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Zou, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Escherichia coli and HPV16 coinfection may contribute to the development of cervical cancer. Virulence 2024, 15, 2319962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, J.G.; Lepine, C.; Morini, A.; Brunet, A.; Veyer, D.; Brochard, C.; Mirghani, H.; Péré, H.; Badoual, C. HPV Detection in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas: What Is the Issue? Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, S.K.; Alblooshi, S.S.E.; Yaqoob, R.; Behl, S.; Al Saleem, M.; Rakha, E.A.; Malik, F.; Singh, M.; Macha, M.A.; Akhtar, M.K.; et al. Human papilloma virus (HPV) mediated cancers: an insightful update. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagón, T.; Franco, E.L.; Tejada, R.; Vaccarella, S. Epidemiology of HPV-associated cancers past, present and future: towards prevention and elimination. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, J.K. HPV. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 55, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, E.M. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosik, M.; Moranova, L.; Izadi, N.; Strmiskova, J.; Sebuyoya, R.; Holcakova, J.; Hrstka, R. Advanced technologies towards improved HPV diagnostics. J. Med Virol. 2024, 96, e29409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontham, E.T.H.; Wolf, A.M.D.; Church, T.R.; Etzioni, R.; Flowers, C.R.; Herzig, A.; Guerra, C.E.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Shih, Y.T.; Walter, L.C.; et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Serrano, B.; Roura, E.; Alemany, L.; Cowan, M.; Herrero, R.; Poljak, M.; Murillo, R.; Broutet, N.; Riley, L.M.; et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and age-specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2022, 10, e1115–e1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, B.; Ibáñez, R.; Robles, C.; Peremiquel-Trillas, P.; de Sanjosé, S.; Bruni, L. Worldwide use of HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Prev. Med. 2022, 154, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daponte, N.; Valasoulis, G.; Michail, G.; Magaliou, I.; Daponte, A.-I.; Garas, A.; Grivea, I.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Daponte, A. HPV-Based Self-Sampling in Cervical Cancer Screening: An Updated Review of the Current Evidence in the Literature. Cancers 2023, 15, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoszek, E.; Krupa, K.; Skrok, E.; Budzik, M.P.; Deptała, A.; Badowska-Kozakiewicz, A. HPV and Cervical Cancer—Biology, Prevention, and Treatment Updates. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdier, F.R.; Waheed, D.-E.; Nedjai, B.; Steenbergen, R.D.; Poljak, M.; Baay, M.; Vorsters, A.; Van Keer, S. DNA methylation as a triage tool for cervical cancer screening – A meeting report. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 41, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennareddy, S.; Chen, S.; Levinson, C.; Genden, E.M.; Posner, M.R.; Roof, S.A. Circulating tumor DNA in human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer management: A systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2025, 164, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kore, V.B.; Anjankar, A. A Comprehensive Review of Treatment Approaches for Cutaneous and Genital Warts. Cureus 2023, 15, e47685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J.T. Developing an HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts. Vaccine 2007, 25, 3001–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Ebihara, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Noda, K. Efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16 and 18) vaccine (GARDASIL) in Japanese women aged 18–26 years. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavonen, J.; Jenkins, D.; Bosch, F.X.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Chow, S.-N.; Apter, D.L.; Kitchener, H.C.; Castellsague, X.; et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paavonen, J.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Chow, S.-N.; Apter, D.; Kitchener, H.; Castellsague, X.; Teixeira, J.C.; Skinner, S.R.; et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet 2009, 374, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtinen, M.; Paavonen, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Jaisamrarn, U.; Garland, S.M.; Castellsagué, X.; Skinner, S.R.; Apter, D.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; et al. Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildesheim, A.; Wacholder, S.; Catteau, G.; Struyf, F.; Dubin, G.; Herrero, R. Efficacy of the HPV-16/18 vaccine: Final according to protocol results from the blinded phase of the randomized Costa Rica HPV-16/18 vaccine trial. Vaccine 2014, 32, 5087–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Pan, W.; Jin, L.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Gao, C.; Ma, D.; Liao, S. Human papillomavirus vaccine against cervical cancer: Opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett. 2020, 471, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pils, S.; Joura, E. From the monovalent to the nine-valent HPV vaccine. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W. H. “Hpv vaccine global market study april 2022.” pp.1680-1686. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-hpv-vaccine-global-market-study-april. 24 April 2022.

- Organization, W. H. Human papillomavirus vaccines: Who position paper, 2022 update. 2022.

- Benedetto Simone, Paloma Carrillo-Santisteve and P. Lopalco. Guidance e. Introduction of hpv vaccines in european union countries—an update. 2012.

- Phillips M, Morais E, A. T. Kothan S, Parellada C, Cashat M and e. al. “Evolution of gender-neutral hpv vaccination in national immunization programs around the world.” 32nd International Papillomavirus conference., Sydney, 2018. p. 545.

- Wheeler, C.M.; Kjaer, S.K.; Sigurdsson, K.; Iversen, O.-E.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Perez, G.; Brown, D.R.; Koutsky, L.A.; Tay, E.H.; García, P.; et al. The Impact of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus (HPV; Types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 Virus-Like Particle Vaccine on Infection and Disease Due to Oncogenic Nonvaccine HPV Types in Sexually Active Women Aged 16–26 Years. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakak, L.; Huber, V.M.; Rühli, F.; Bender, N. Sex difference in the immunogenicity of the quadrivalent Human Papilloma Virus vaccine: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Saura-Lázaro, A.; Montoliu, A.; Brotons, M.; Alemany, L.; Diallo, M.S.; Afsar, O.Z.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Mosina, L.; Contreras, M.; et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010–2019. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Valent, F.; Comar, M.; Suligoi, B.; Salfa, M.C.; Gianfrilli, D.; Sesti, F.; Restivo, V.; Casuccio, A. ; ESPRIT Study Collaboration Group Study protocol for a pre/post study on knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding STIs and in particular HPV among Italian adolescents, teachers, and parents in secondary schools. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1414631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesic, V.; Carcopino, X.; Preti, M.; Vieira-Baptista, P.; Bevilacqua, F.; Bornstein, J.; Chargari, C.; Cruickshank, M.; Erzeneoglu, E.; Gallio, N.; et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), the European College for the Study of Vulval Disease (ECSVD), and the European Federation for Colposcopy (EFC) consensus statement on the management of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, C.; Stoney, T.; Hutton, H.; Parrella, A.; Kang, M.; Macartney, K.; Leask, J.; McCaffery, K.; Zimet, G.; Brotherton, J.M.; et al. School-based HPV vaccination positively impacts parents’ attitudes toward adolescent vaccination. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4190–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.D.; Spratling, R. Adolescent Self-Consent for the HPV Vaccine and the Effects on Vaccine Rates. J. Pediatr. Heal. Care 2024, 38, 932–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunelli, L.; Bravo, G.; Romanese, F.; Righini, M.; Lesa, L.; De Odorico, A.; Bastiani, E.; Pascut, S.; Miceli, S.; Brusaferro, S. Beliefs about HPV vaccination and awareness of vaccination status: Gender differences among Northern Italy adolescents. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, M.; Bruni, L.; Elfström, M.; Gray, P.; Logel, M.; Mariz, F.C.; Baussano, I.; Vänskä, S.; Franco, E.L.; Dillner, J. Scientific approaches toward improving cervical cancer elimination strategies. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraceni, S.; Campisciano, G.; Contini, C.; Comar, M. HPV genotypes distribution in Chlamydia trachomatis co-infection in a large cohort of women from north-east Italy. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016, 65, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-W.; Long, H.-Z.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, H.-Y.; Wen, D.-D.; Gao, L.-C. From Microbiome to Inflammation: The Key Drivers of Cervical Cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Liu, Z.; Sun, T.; Zhu, L. Cervicovaginal microbiome, high-risk HPV infection and cervical cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 287, 127857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, L.; Mtshali, A.; Mzobe, G.; Liebenberg, L.J.; Ngcapu, S. Role of Immunity and Vaginal Microbiome in Clearance and Persistence of Human Papillomavirus Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 927131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisciano, G.; Iebba, V.; Zito, G.; Luppi, S.; Martinelli, M.; Fischer, L.; De Seta, F.; Basile, G.; Ricci, G.; Comar, M. Lactobacillus iners and gasseri, Prevotella bivia and HPV Belong to the Microbiological Signature Negatively Affecting Human Reproduction. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2019, 10, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegari, A.; Kheyrolahzadeh, K.; Khatibi, S.M.H.; Sharifi, S.; Memar, M.Y.; Vahed, S.Z. The Battle of Probiotics and Their Derivatives Against Biofilms. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, ume 13, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; Wang, D.; Liu, H.; Shen, M.; Yu, H. Two strains of probiotic Lactobacillus enhance immune response and promote naive T cell polarization to Th1. Food Agric. Immunol. 2019, 30, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghinezhad-S, S.; Keyvani, H.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Donders, G.G.G.; Fu, X.; Mohseni, A.H. Twenty years of research on HPV vaccines based on genetically modified lactic acid bacteria: an overview on the gut-vagina axis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 78, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, A.H.; Taghinezhad-S, S.; Keyvani, H.; Razavilar, V. Extracellular overproduction of E7 oncoprotein of Iranian human papillomavirus type 16 by genetically engineered Lactococcus lactis. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghinezhad-S, S.; Mohseni, A.H.; Keyvani, H.; Razavi, M.R. Phase 1 Safety and Immunogenicity Trial of Recombinant Lactococcus lactis Expressing Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6 Oncoprotein Vaccine. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 15, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, H.; Du, X.; Wang, J. Mucosal vaccine delivery: A focus on the breakthrough of specific barriers. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3456–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-C.; Ouh, Y.-T.; Sung, M.-H.; Park, H.-G.; Kim, T.-J.; Cho, C.-H.; Park, J.S.; Lee, J.-K. A phase 1/2a, dose-escalation, safety and preliminary efficacy study of oral therapeutic vaccine in subjects with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 30, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Valent, F.; Comar, M.; Suligoi, B.; Salfa, M.C.; Gianfrilli, D.; Sesti, F.; Capra, G.; Casuccio, A.; De Luca, E.; et al. Knowledge About HPV and the HPV Vaccine: Observational Study on a Convenience Sample of Adolescents from Select Schools in Three Regions in Italy. Vaccines 2025, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).