1. Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) is one of the most common Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) among adults; of which HPV 16, 18, 31, and 35–(high-risk types) [

1] are the most prevalent HPV genotypes among sexually active adults in the Northern part of Nigeria [

2,

3]. These high-risk HPV genotypes, especially HPV 16 and 18 have been clinically proven to be the leading cause of cervical cancer in women across low-income African countries [

4,

5]. However, the low-risk (11, 42, 61, 70, and 81) HPV genotypes are capable of causing HPV genital warts [

6]. Numerous studies has revealed that HPV is also highly associated with the growth of HPV genital warts in both men and women [

7,

8]. In most cases, persons with healthy immune system can be HPV free overtime even after being infected. An HPV vaccine-built immunity and other types of preventative vaccines (such as toxoids, Messenger Ribonucleic Acid (mRNA), and subunit vaccines [

9]), alongside with some other factors (such as healthy weight, healthy food, exercise, staying away from excessive alcohol intake and smoking [

10]) can effectively repel against persistent HPV infections within two years before it develops into a tumor [

11] and other immunological diseases [

12] in the presence of a healthy immune system. However, North-central Nigerian adults are faced with some challenges which have contributed to the spread of HPV infection as against the unavailability of some protective measures due to the lack of knowledge about HPV in general, abject poverty (resulting into inability to: purchase HPV vaccines, eat healthy food, and attend paid HPV-related seminars), individual’s ethical imperatives, unavailability of free medical services, and some National policies that are not in place to make HPV vaccine available at a low cost and enforce it as a part of the routine vaccination program [

13]. Due to these challenges, there have been increase in the cases of HPV infection and cervical cancer mortality rate among women in the North-central part of Nigeria yearly [

14]. According to the statistical report gathered by the ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre) in October 2021, among other kinds of cancers, HPV-related (HPV 16 and 18) cancer occurrence in the female population of ages ≥15 years in Nigeria was 66.9% amidst 56.2 million total females who are at risk of cervical cancer [

15].

Some epidemiological studies have also in the past revealed demographic variations among low-income settlements in Nigeria and it association between HPV infection [

6]. For instance, a study conducted for 16 years in a rural area in Nigeria reveals that inaccessibility to childhood and adolescent routine immunization as a preventive measure for preventable diseases [

16] is more prevalent in low- and middle-income areas in Nigeria causing several infant mortality and other sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries causing several infant mortality [

17]. Thereby, putting non-HPV vaccinated adults at risk of persistent HPV infections. Similarly, a study conducted among adolescent and young girls in Jos, Nigeria also shows that the lack of HPV vaccine and lack of knowledge about HPV enhanced the prevalence of HPV among the population [

6]. Hence, it is have been proven that the availability of free medical services to provide organized HPV programmes, HPV vaccines, and HPV testing and cervical cancer screenings using cytology/visual inspection/colposcopic biopsy in low-income settlements would help to mitigate HPV infection cases and cervical cancer mortality rate in Nigeria [

2,

5,

18].

In this study, we explored the demographic predictors of self-reported [

19] HPV-infections and HPV-genital warts infection among low-income students, non-academic, and academic (lecturers) staff of Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (IBB) University located in Lapai, Nigeria considering their income rate as compared to the country’s minimum wage and if they have reported to have had HPV infection in the past. Furthermore, age as another demographic factor was also analyzed to observe if the population’s age is likely to affect their monthly income rate. Abject poverty as one of the predictors of HPV infection was considered for analysis in this study, especially in low-income and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) (as in Nigeria) [

20] where her citizens cannot fend for their medical services in the presence of a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita at

$2,157 as recorded in 2019 by World Bank collection of development indicators.

2. Motivation—Problem Definition

In the absence of knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer even in an academic/educational environment, there is a likelihood that there would be cases of HPV infection among a population. Sadly, the male population in the society are not aware of their HPV status. Thereby, causing females the risk of contracting HPV which further develops into cervical cancer in future [

21]. Clinical research has revealed that HPV takes 10–15 years to develop into abnormal cells [

22]. The purpose of this paper is to reveal the risk factors of HPV infection and genital warts in an academic environment and study those who have self-reported cases of HPV infection and genital warts using statistical methods. Our results can be adopted by Niger state Ministry of Health for HPV awareness in an academic setting, healthcare sectors, private organizations, and by individuals as a guide for safe sexual practices and knowledge about HPV.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This was an online cross-sectional study among students, non-academic, and academic staff of Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida university, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria

. Putting to consideration the privacy of the participants, Nigerian citizen have right to their private data and the Nigerian constitution guarantees privacy protection to all citizens. Hence, the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) was enforced during data collection [

23].

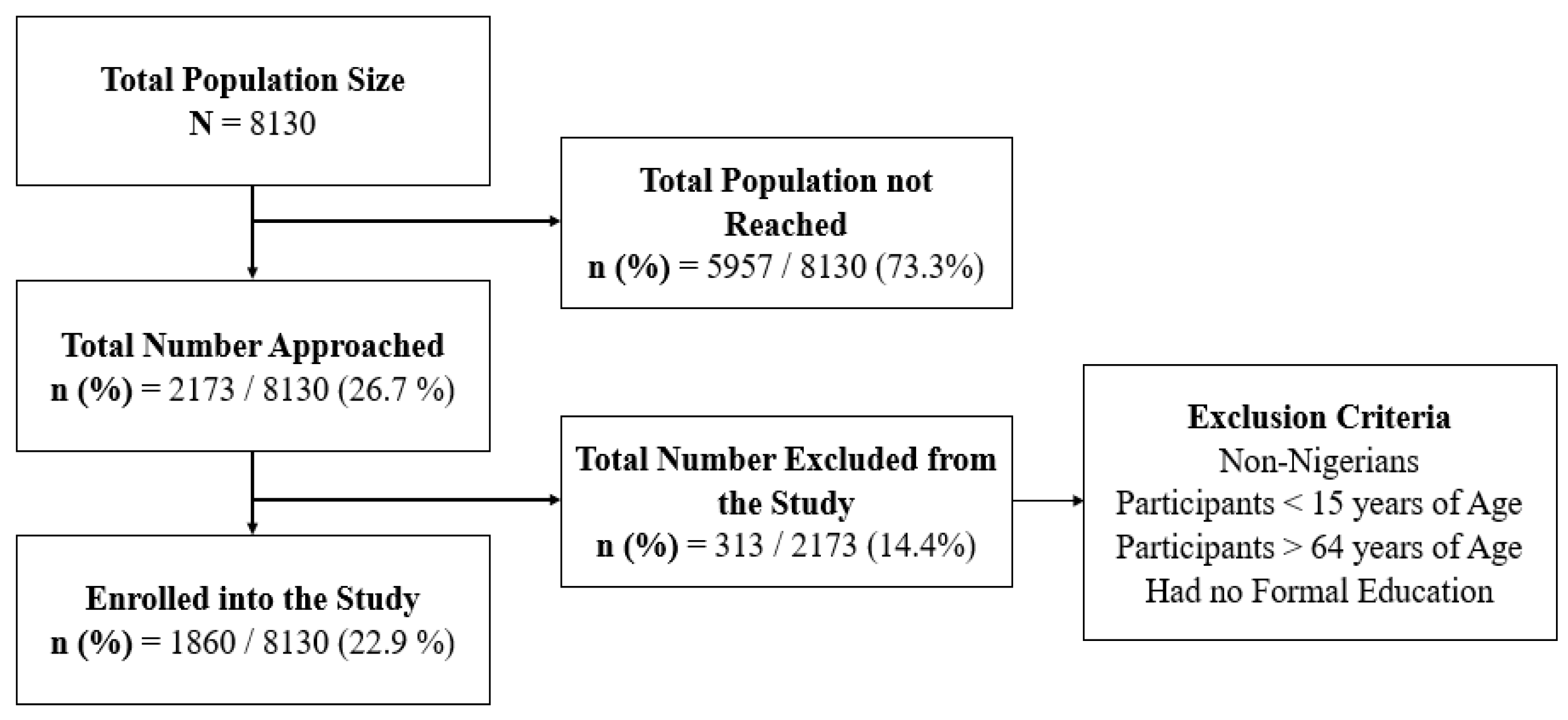

3.1.1. Sample Size

The sample size determination formula for a cross-sectional study was used in this study.

where;

n = minimum sample size.

z = standard normal deviation of 95% confidence level; corresponds to a value of 1.96.

p = Record of HPV genital warts from similar studies in Southwestern, Nigeria was (0.22) [

24].

e = level of precision of 0.04.

q = 1 - p; 1 - 0.22 = 0.78.

deff = 1.98, a design effect (deff) of 1.98 was factored because the study cut across clusters (i.e., cluster of students, non-academic, and academic staff).

n = 1615

na (after adjusting for a 10% non-response rate) = 1860.

A total of 1860 eligible people who completed the online questionnaires were considered/enrolled for this study.

Figure 1.

Study Enrolment Flowchart.

Figure 1.

Study Enrolment Flowchart.

3.1.2. Sampling Method

Having established a high incidence of sexual behavior [

25] which is a risk factor of HPV infection among university students and staff [

26,

27]. Hence, we carried out this study among the university community, at Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida university, Lapai in Niger state, Nigeria. The IBB university is located in the North-Central region of Nigeria and has a student capacity of about 7000, 820 non-academic, and 310 academic staff. The data was collected using an online data collection tool (Google survey form). The questionnaire was set up on the google survey form and the function that restricts multiple responses from participants was enabled.

3.1.3. Study Instrument and Data Collection

A structured questionnaire that captured the demographics characteristics, information about HPV and Sexual Health, and Knowledge about early sex and HPV-16 and -18 genotype. In order to improve the response rate, we did an awareness (live event) about the study through a Facebook platform during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 but data collection lasted between 2019–2022. The lead investigator and a group of gynecologists in Nigeria and the United State of America facilitated the event. During the event, participants were asked to fill an online questionnaire–the Human papillomavirus (HPV) and Cervical Cancer Risk Assessment (HCRA) Tool (also known as the HPV Assessment Test (HAT) Tool [

1]). The link to the online questionnaire (Google form) was distributed via Facebook. Google form is an electronic platform designed for creating surveys, quizzes, and knowledge evaluations. The google form can be created and administered on personal computers, mobile devices, as well as tablets. Some of its important features are real-time data capturing, friendly user interface, limiting responses to once per person etc. The google form has proven to be effective for research data collection and other data capturing activities [

28].

3.1.4. Study Variables

The outcome variable for this study was self-reported medical record/history of HPV genital warts (Yes or No). The explanatory variables included the 1. Demographic variables: Gender [Male, Female]; age group [15–64]; level of education [High school/equivalence, and BSc/MSc/Doctorate degree)]; Income in USD ($) [Below 100, 100-200, above 200], $100 ≡ #45,000 Nigerian currency; Marital Status [Currently in a union, not in a union (single/divorced)]. 2. Sexual Health/Behavior: Sexual intercourse [Yes, No]; Age at first sex [15–21–30, >30 years]; Number of the sexual partner in a lifetime [1, 2–4, >4]; Kind of sex [vaginal only, others (anal, oral, and vaginal)]; Knowledge about early sex [Yes, No]; and Protected sex, defined as the use of condom for sexual intercourse [unprotected, protected]. 3. Information on HPV factors: Vaccinated against HPV [Yes, No]; HPV seminar attendance [Yes, No]; and knowledge of HPV-16 and -18 genotypes [Yes, No].

3.2. Data Analysis

We summarized all the variables using frequencies and percentages (descriptive statistics). Also, a chi-square test of association was done to test the association between the participants’ profiles and self-reported medical record/history of HPV genital warts. We examined the factors associated with HPV infection by fitting a binary logistic regression and an adjusted Odds ratio (AdjOR) was reported.

3.2.1. Model Expression

The model expression implemented for statistical analysis is the logistic regression model [

7].

where;

Log is the probability of HPV genital warts up to ith participant.

X1 denote sexual health, X2 represent the HPV factors (HPV vaccination, HPV seminar), and X3 denote Demographic variables.

0 is the model intercept while β1, β2, and β3 denote the coefficients for sexual health and demographic characteristics.

is the error term which was assumed to follow the binomial distribution.

Stata MP version 15 was used for statistical analysis, and P-values <0.05 were considered significant at a 95% confidence interval (CI).

3.3. Ethical Considerations

The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Niger State Ministry of Health Review Committee (protocol number: ERC PIN/2022/08/17 and approval number: ERC PAN/2022/08/17) in Minna, Niger state, Nigeria. Participants provided consent by clicking the “accept to participate” button after reading the informed consent on the first page. In order to assure the privacy and confidentiality of the participants, all participants voluntarily participated in this study and no identifying information was captured. Since data was collected online, the study has no/minimal risk to the health of the participants, their environment, and their relatives.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study

The results in

Table 1 below reveal the demographic characteristics of the students, non-academic, and academic staff who participated in this study (n = 1860). The participants’ age ranged from 15–64years with Mean 32.1 ± 7.13SD. The study contained more female than male participants, whereby 1750 (94.1%) of them were females and 110 (5.9%) were males. Most of the participants were millennials; thus, 1512 (81.3%) were aged of 26–40 years, while 151 (8.1%) and 197 (10.6%) were aged 15–25 years and >40 years respectively. Only 136 (7.3%) had High-school education and 1724 (92.7%) had a BSc. or MSc. or Doctoral degree. Most of the participants recorded having an average livelihood, where 739 (39.7%) earned below 100 USD monthly, 27.4% earned between 100–200 USD, and 32.9% earned above 200 USD monthly. The majority of the population of 1369 (73.6%) were in a marital union, and 26.4% were not in a marital union.

4.2. Information About HPV and Sexual Health of Participants

The results in

Table 2 below present the information about the participants self-reported HPV infection and sexual health. Mostly, 1843 (99.1%) were sexually exposed, where about a half (49.4%) had early sexual debut from age 15–20 years, 875 (47.5%) experienced sexual debut between the ages of 21–30 years, and 57 (3.1%) had sexual debut at age ≥31 years. It was observed that 569 (30.9%) participants have had only one sexual partner in a lifetime, 636 (34.5%) have had 2–4 sexual partners, and 638 (34.6%) have had ≥ 4 sexual partners. Among those who had more than one sexual partner, 934 (73.3%) practiced unprotected sex and 340 (26.7%) practiced protected sex, 1790 (97.1%) practiced vaginal sexual intercourse and 53 (2.9%) practiced others (anal, oral, and vaginal) sexual intercourse. Furthermore, only 528 (28.4%) attended HPV seminar. Also, the rate of HPV vaccination was low, wherefore just 107 (5.8%) among the participants have been vaccinated against HPV infection. Finally, 74 (4.0%) of the participants reported that they have had medical records of HPV genital warts while 55 (3.0%) have had medical records of HPV-16 and -18 genotype infections.

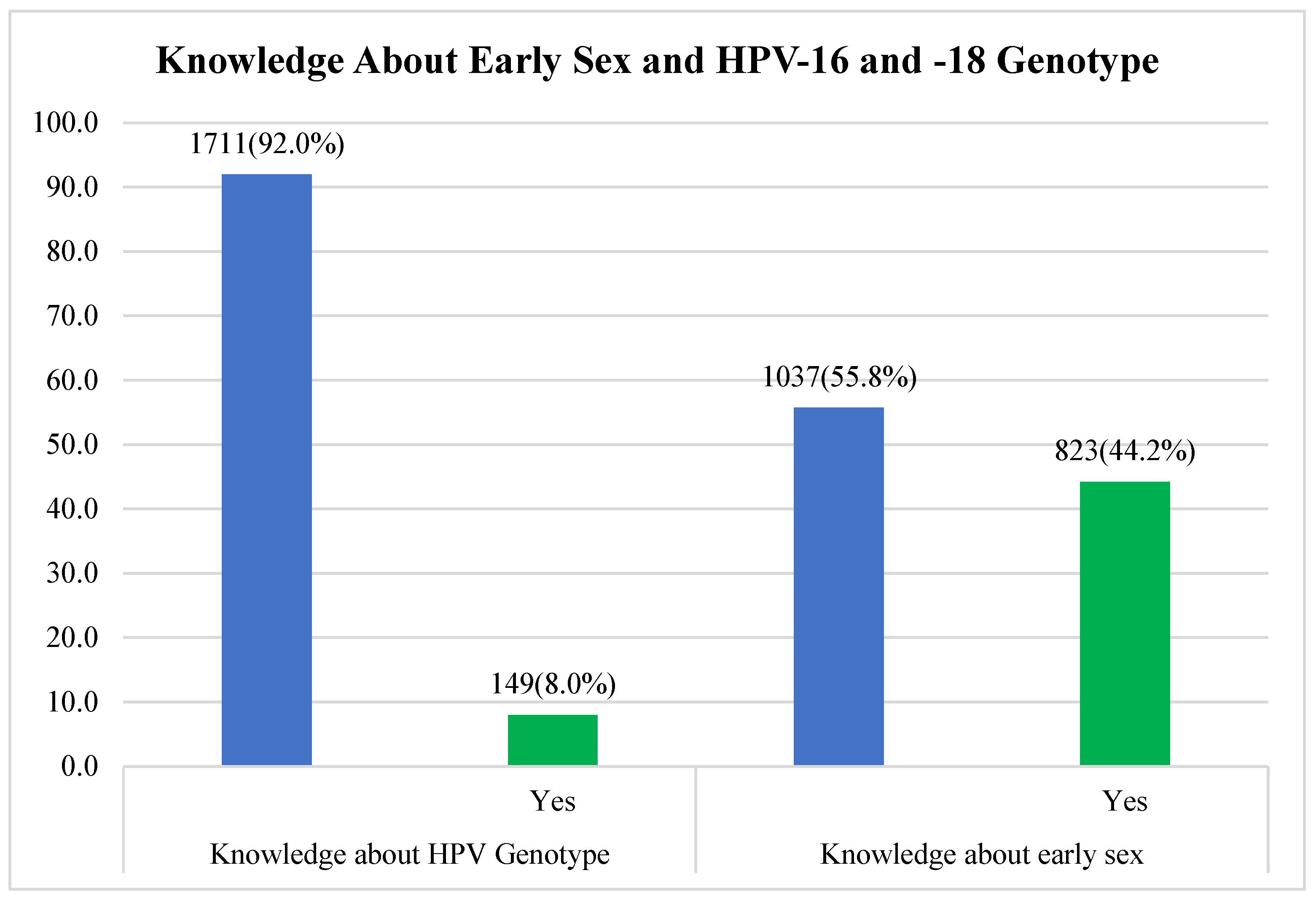

4.3. The Participants’ Knowledge about the Association between Early Sex and HPV-16 and -18 Genotypes

Figure 2 below shows the population’s level of knowledge about the association between early sex and HPV-16 and -18 genotypes. Quite a number of the participants agreed that early sex is associated with HPV infection which means that 822 (44.2%) have knowledge about early sex, but knowledge about HPV-16 and -18 genotypes was low as statistical analysis revealed that only 149 (8.0%) among the participants agreed to have any knowledge about HPV genotypes 16 and 18.

4.4. Association between HPV Infection and Participants’ Profile

At the time of the survey distribution, results in

Table 3 below show the association between participants who recorded self-reported HPV infection and the participants’ profile using chi-square test. The rate of HPV infection was 13 (8.6%) among those aged 15–25 years compared to 56 (3.7%) and 5 (2.5%) rate among participants aged between 26–40 years and 41–64 years respectively, P = 0.007. There was a preponderance of 27 (5.5%) of HPV infection among those who were not in a marital union compared to married participants, P = 0.045. Similarly, more 48 (5.1%) of those who practiced unprotected sexual intercourse had HPV infection compared to those who practiced protected sexual intercourse, P = 0.096. Also, HPV infection was more common 5 (9.4%) among those who practiced other (anal, oral, vaginal) kind of sex compared to those who practice vaginal sex only, P = 0.083. HPV infection was 14 (9.4%) among those who have knowledge about HPV-16 and -18 genotype compared to those 60 (3.5%) who do not, P<0.001. The proportion of HPV infection was slightly higher 42 (5.1%) among participants who had knowledge about early sex compared to those who don’t have knowledge about early sex, P = 0.027.

4.5. Factors Associated with HPV Genital Warts Infection among Students, Non-academic, and Academic Staff in North-Central Nigeria

The results in

Table 4 represent the factors associated with HPV infection among the study participants using logistic regression model. Only two variables had a significant association with HPV infection. The likelihood of HPV infection was lower among those aged between 26–40 years (

AdjOR = 0.45, CI:0.22–0.89, p = 0.024), and 41–64 years (

AdjOR = 0.31, CI: 0.10–0.95, p = 0.041) compared to those aged 15–20 years.

5. Discussion

This study examined 1860 students, non-academic, academic staff and in North-central Nigeria on their demographic characteristics, their awareness/knowledge about HPV infections and HPV genotypes, and their sexual health and practices. The findings observed are a concern to public health.

Considering the demographic characteristics, we observed that the study sample was representative as it includes both high-school/equivalence (low-levelled) and BSc, MSc, Doctorate Degree (high-levelled) elite participants between the ages of 15–64 years, whereas most were between the age of 26–40 years. However, the gender distribution was not even as there were less male than female in the study. Although, the survey also included some questions about cervical cancer, and this might be why the male participants were not interested in taking the survey. The distribution of the participants based on their monthly income was fairly even. The distribution of the participants’ based on their marital status was skewed; where most of the participants indicated to be in a union (married or separated) which is because the rate of divorce among ever married couples is low in the North-central region of Nigeria as compared to other regions [

29]. This skewedness is expected because the North-central part of Nigeria is mostly populated by Muslims who believe that their religion detests divorce, according to Sunan Abu-Dawud, Book 6:2173 [

30]. Also a study conducted to examine cancer of the cervix in Zaria [

31] and Lagos [

32] revealed that most of the study participants were married which validates our result for having more participants who are currently in a union.

The result of the participants’ sexual behavior shows that a large majority of the participants reported to have had sexual intercourse in their lifetime and of which had their first experience between the age of 15–20 years and more have had >4 partners in a lifetime. These results corroborates with other studies’ results that have explored the predictors of HPV among males and females population, where early sex (≤ 20 years) is common among early and late adolescents in Nigeria [

33] having 1 or more sexual partners before the age of 20 years [

15], and having >4 sexual partners in a lifetime [

34]. Furthermore, a vast number of the participants were also not concerned about practicing safe sex before they got into a union. We excluded those who indicated to have had only one sexual partner and analyzed those who have had >1 sexual partners (1274 participants) in a lifetime; the result revealed that most of the participants (73.3%) who fall under these group do not practice safe sex (with the use of condoms). This aligns with results from other studies that have reported that condoms are not widely used among non-married people in Nigeria [

35]. A survey distributed by NOIpolls, in alliance with the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) and AIDS HealthCare Foundation (AHF) in 2020 to mitigate the spread of HIV/AIDS reveals that only 34% of Nigerians indicated that they use condoms during sexual intercourse [

36]. This study also reveals that the combination anal, oral, and vaginal sex was low among the population, as 97.1% participants mostly practiced vaginal sex only. This is because the population understudy might be affected by religious beliefs and detest the act of oral and anal sex. Another study also revealed that vaginal sex (95.2%) was mostly practiced among adolescents in Nigeria who were examined for self-reported HIV transmission [

37].

The proportion of the participants with the awareness of HPV-related seminar and HPV vaccine was low (28.4% and 5.8% respectively) similar to the corresponding percentage from a study that revealed that only 9.0% have had about HPV and cervical cancer program/seminar [

38] while another study that examined secondary school female teachers in Lagos who have had HPV vaccine (2.2%) given to their teenage children [

32].

The chi-square test was used to measure the association between self-reported HPV infection and participants’ profile. Statistical analysis shows that there was a significant association between HPV infection and the participants’ aged between 26–40 years (Fisher’s exact, p = 0.007), not in a marital union (Fisher’s exact, P = 0.045), who had no knowledge about HPV-16 and -18 genotypes (Fisher’s exact, P <0.001), and who had no knowledge about early sex (Fisher’s exact, P = 0.027). The result about the participants who have self-reported having HPV infection correlated with the results from other studies where there exist an association between the population under study’ aged ≤ 30 years (Fisher’s exact, p = 0.006) [

39], those with unstable marital status or single with multiple sexual partners (Fisher’s exact, p = 0.022 and p = 0.001 respectively) [

40], and lack of knowledge about HPV (Fisher’s exact, p < 0.0001) [

41] as predictors of HPV infection.

Regression analysis also reveals the factors predicting HPV genital warts among the population under study. Result shows that participants between the ages of 26–64 years have reported to likely be carriers of HPV genital warts; where 26–40 years (

AdjOR = 0.45, CI:0.22–0.89) and 41–64 years (

AdjOR = 0.31, CI: 0.10–0.95). Thus, the participants between the ages of 26–40 years have a higher odd as compared to the those between the ages of 41–64 years (p-value, p = 0.024 and p =0.041 respectively). This result aligns with previous studies where ages lower than or equal to 30 years are more likely to be infected than those who are over 45 years [

15,

39,

42,

43]. Conversely, the variable gender, marital status, kind of sex practiced, protected sex, and knowledge about early sex were not significantly associated with HPV infection in this study.

5.1. Study Strength and Limitations

Availability of a large sample size is one of the strengths of this study and it is also the first study to be conducted in Lapai, Niger state. It was also an achievement to include the male population in this study. However, one of the limitations faced by the study is that we had an extremely low sample size of the male population as compared to the female population. Therefore, we acknowledge that the male population in this study was not well represented. An additional significant limitation of this study is that we have conducted the study based on self-reported data only. Hence, some responses provided by the participants to sensitive questions may have been based on bias. Furthermore, during data collection we did not provide categorization for students, non-academic, and academic staff; thus, the Human papillomavirus (HPV) and Cervical Cancer Risk Assessment (HCRA) Tool (questionnaire) has been modified and currently used for the last phase of the research field work for data collection.

5.2. Conclusions

HPV infection was high among participants (who have self-reported having medical/history of HPV-16 and -18 genotype) between the ages of 26–40 years, currently not in a union, and had no knowledge about HPV-16/-18 genotypes and the consequences of early sexual debut. Also, participants >26 years of age are likely to be carriers of HPV genital warts. These factors have been revealed as the most important predictors peculiar to IBB university students, non-academic, and academic staff in this study. Hence, the need for awareness about HPV is required/a must for the safety and well-being of IBB university community. As a concern and solution, this situation can therefore suggest the need for free HPV vaccination routine and programs in universities in Nigeria, as well as to stress the importance of sex education among adults through awareness programs in the academic environment populated with low- and middle-income earners in Nigeria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of research: O.M.O. and M.K.; methodology: O.M.O., O.D.E., and M.K.; software: O.M.O. and O.D.E.; formal analysis: O.M.O. and O.D.E.; investigation: O.M.O.; resources: O.M.O. and M.K.; data curation: O.M.O.; writing—original draft preparation: O.M.O., O.D.E., and H.M.; writing—review and editing: O.M.O., O.D.E., H.M., and M.K.; visualization: O.M.O., O.D.E., H.M., and M.K.; supervision: M.K.; project administration: O.M.O. and M.K.; funding acquisition: M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology NRDI Office within the framework of the Infocommunications and Information Technologies National Laboratory. The authors hereby thank the Eötvös Loránd Research Network Secretariat under grant agreement no. ELKH KÖ-40/2020 (Development of cyber-medical systems based on AI and hybrid cloud methods, the GINOP-2.2.1-15-2017-00073 “Telemedicina alapú ellátási formák fenntartható megvalósítását támogató keretrendszer kialakítása és tesztelése” project, and the 2019-1.3.1-KK-2019-00007, In-novációs szolgáltató bázis létrehozása diagnosztikai, terápiás és kutatási célú kiberorvosi rend-szerek fejlesztésére” project for their financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Niger State Ministry of Health Ethical Review Committee (NSMOH ERC) (protocol number: ERC PIN/2022/08/17 and approval number: ERC PAN/2022/08/17) in Minna, Niger state, Nigeria. Participants provided consent by clicking the “accept to participate” button after reading the informed consent on the first page of the online survey. In order to assure the privacy and confidentiality of the participants, all participants vol-untarily participated in this study and no identifying information was captured. Since data was collected online, the study has no/minimal risk to the health of the participants, their environment, and their relatives.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The HPV and CC data collected during this project and processed for this research publication as part of this study were submitted to the Niger State Ministry of Health Ethical Review Committee (NSMOH ERC) and are available upon request. Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Niger State Ministry of Health Ethical Review Committee (NSMOH ERC) in Minna, Niger state, Nigeria for their support in granting us permission for data collection in Niger state and their support during the dissemination of the first part of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- O. M. Omone and M. Kozlovszky, “HPV and Cervical Cancer Screening Awareness: A Case-control Study in Nigeria,” in 2020 IEEE 24th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES), Jul. 2020, pp. 145–152. [CrossRef]

- A. U. Emeribe et al., “The pattern of human papillomavirus infection and genotypes among Nigerian women from 1999 to 2019: a systematic review,” Ann Med, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 944–959, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Manga et al., “Epidemiological patterns of cervical human papillomavirus infection among women presenting for cervical cancer screening in North-Eastern Nigeria,” Infectious Agents and Cancer, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 39, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Ramogola-Masire, R. Luckett, and G. Dreyer, “Progress and challenges in human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in southern Africa,” Curr Opin Infect Dis, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 49–54, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Louie, S. de Sanjose, and P. Mayaud, “Epidemiology and prevention of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive review,” Trop Med Int Health, vol. 14, no. 10, pp. 1287–1302, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Cosmas, L. Nimzing, D. Egah, A. Famooto, S. N. Adebamowo, and C. A. Adebamowo, “Prevalence of vaginal HPV infection among adolescent and early adult girls in Jos, North-Central Nigeria,” BMC Infect Dis, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 340, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. M. Omone, A. U. Gbenimachor, L. Kovács, and M. Kozlovszky, “Knowledge Estimation with HPV and Cervical Cancer Risk Factors Using Logistic Regression,” in 2021 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), May 2021, pp. 000381–000386. [CrossRef]

- K. R. McBride and S. Singh, “Predictors of Adults’ Knowledge and Awareness of HPV, HPV-Associated Cancers, and the HPV Vaccine: Implications for Health Education,” Health Educ Behav, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 68–76, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- “What are the Different Types of Vaccines?,” News-Medical.net, Jul. 28, 2020. https://www.news-medical.net/health/What-are-the-Different-Types-of-Vaccines.aspx (accessed Nov. 02, 2022).

- CDC, “Enhanced Immunity,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jan. 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/features/enhance-immunity/index.html (accessed Nov. 02, 2022).

- D. SONG, H. LI, H. LI, and J. DAI, “Effect of human papillomavirus infection on the immune system and its role in the course of cervical cancer,” Oncol Lett, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 600–606, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Childs, P. C. Calder, and E. A. Miles, “Diet and Immune Function,” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 1933, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Brown and M. Folayan, “Barriers to uptake of human papilloma virus vaccine in Nigeria: A population in need,” Niger Med J, vol. 56, no. 4, p. 301, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Musa et al., “Cervical cancer survival in a resource-limited setting-North Central Nigeria,” Infectious Agents and Cancer, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 15, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- “Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado JJ, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Nigeria. Summary Report 22 October 2021.pdf.” Accessed: Nov. 11, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/NGA.pdf.

- CDC, “Immunization Schedules for 18 & Younger,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Feb. 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html (accessed Nov. 04, 2022).

- A. A. Ahonkhai et al., “Lessons for strengthening childhood immunization in low- and middle-income countries from a successful public-private partnership in rural Nigeria,” Int Health, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 632–638, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI), “Epidemiologic and Molecular Features of Cervical Cancer in Nigeria - Project Itoju (Care),” clinicaltrials.gov, Clinical trial registration NCT00804466, Nov. 2020. Accessed: Nov. 09, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00804466.

- B. Beszédes, K. Széll, and G. Györök, “A Highly Reliable, Modular, Redundant and Self-Monitoring PSU Architecture,” ACTA POLYTECH HUNG, vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 233–249, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Brisson et al., “Impact of HPV vaccination and cervical screening on cervical cancer elimination: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries,” Lancet, vol. 395, no. 10224, pp. 575–590, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Australia, “What are the risk factors for cervical cancer?,” Dec. 18, 2019. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/cervical-cancer/awareness (accessed Mar. 10, 2022).

- “Cervical cancer.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed Mar. 14, 2022).

- “Law in Nigeria - DLA Piper Global Data Protection Laws of the World.” https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/index.html?t=law&c=NG (accessed Aug. 08, 2022).

- P. F. Schnatz, N. V. Markelova, D. Holmes, S. R. Mandavilli, and D. M. O’Sullivan, “The prevalence of cervical HPV and cytological abnormalities in association with reproductive factors of rural Nigerian women,” J Womens Health (Larchmt), vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 279–285, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Garai-Fodor, “The Impact of the Coronavirus on Competence, from a Generation-Specific Perspective,” Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, vol. 19, no. 8, 2022.

- O. A. Uthman, “Does it really matter where you live? A multilevel analysis of social disorganization and risky sexual behaviours in sub-Saharan Africa.,” DHS Working Papers, no. 78, pp. 1–29, 2010.

- J. A. Menon, S. O. C. Mwaba, K. Thankian, and C. Lwatula, “Risky sexual behaviour among university students,” International STD Research & Reviews, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2016.

- M. N. Jain and V. Karnad, “Online Forms for Data Collection and its Viability in Fashion and Consumer Buying Behavior Survey–A Case Study,” 2017.

- L. F. C. Ntoimo and M. E. Akokuwebe, “Prevalence and Patterns of Marital Dissolution in Nigeria,” NJSA, vol. 12, no. 2, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “SUNAN ABU-DAWUD, Book 6: Divorce (Kitab Al-Talaq).” https://www.iium.edu.my/deed/hadith/abudawood/006_sat.html (accessed Nov. 18, 2022).

- O. Oguntayo, M. Zayyan, A. Kolawole, S. Adewuyi, H. Ismail, and K. Koledade, “Cancer of the cervix in Zaria, Northern Nigeria,” Ecancermedicalscience, vol. 5, p. 219, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Toye, K. S. Okunade, A. A. Roberts, O. Salako, E. S. Oridota, and A. T. Onajole, “Knowledge, perceptions and practice of cervical cancer prevention among female public secondary school teachers in Mushin local government area of Lagos State, Nigeria,” Pan Afr Med J, vol. 28, p. 221, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Makwe, R. I. Anorlu, and K. A. Odeyemi, “Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and vaccines: Knowledge, attitude and perception among female students at the University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria,” JEGH, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 199, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Adebamowo, O. Olawande, A. Famooto, E. O. Dareng, R. Offiong, and C. A. Adebamowo, “Persistent Low-Risk and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infections of the Uterine Cervix in HIV-Negative and HIV-Positive Women,” Front Public Health, vol. 5, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. A. Bolarinwa, K. V. Ajayi, and R. K. Sah, “Association between knowledge of Human Immunodeficiency Virus transmission and consistent condom use among sexually active men in Nigeria: An analysis of 2018 Nigeria Demographic Health Survey,” PLOS Global Public Health, vol. 2, no. 3, p. e0000223, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nike Adebowale-Tambe, “Only 34% of Nigerians use condoms–Survey: Premiunmtimesng; 2020.” https://www.premiumtimesng.com/health/health-news/377202-only-34-of-nigerians-use-condoms-survey.html (accessed Nov. 18, 2022).

- M. O. Folayan, M. Odetoyinbo, B. Brown, and A. Harrison, “Differences in sexual behaviour and sexual practices of adolescents in Nigeria based on sex and self-reported HIV status,” Reprod Health, vol. 11, p. 83, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Enebe et al., “Awareness, acceptability and uptake of cervical cancer vaccination services among female secondary school teachers in Enugu, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study,” Pan Afr Med J, vol. 39, p. 62, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Akarolo-Anthony et al., “Age-specific prevalence of human papilloma virus infection among Nigerian women,” BMC Public Health, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 656, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Kero, J. Rautava, K. Syrjänen, O. Kortekangas-Savolainen, S. Grenman, and S. Syrjänen, “Stable marital relationship protects men from oral and genital HPV infections,” Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 1211–1221, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Iliyasu, H. S. Galadanci, A. Muhammad, B. Z. Iliyasu, A. A. Umar, and M. H. Aliyu, “Correlates of human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge and acceptability among medical and allied health students in Northern Nigeria,” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 452–460, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Vahle et al., “Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Among Women Older than Recommended Age for Vaccination by Birth Cohort, United States 2003‒2016,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 225, no. 1, pp. 94–104, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Okunade, C. M. Nwogu, A. A. Oluwole, and R. I. Anorlu, “Prevalence and risk factors for genital high-risk human papillomavirus infection among women attending the out-patient clinics of a university teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria,” Pan Afr Med J, vol. 28, p. 227, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).