1. Introduction

The eradication of cervical cancer is an important goal in the fight against cancer, as it is the first type of cancer potentially to be eliminated as a public health problem. This cancer shows bimodal age distribution with the first peak at ages 30 - 34 years, due to first Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infection after sexual initiation and a second peak at 65 - 69 years of age due to viral persistence or reactivation of latent HPV.

According to the WHO’s "Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative", three key targets must be reached by 2030 to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem: 90% of girls fully vaccinated against HPV by the age of 15; 70% of women screened using a high-performance test by the age of 35, and again by the age of 45, and 90% of women with adequately treated cervical lesions and invasive cancers. In 2021 the European Commission further pushed the initiative through the Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, by also raising cervical screening coverage to 90% for member countries of the European community.

The estimated number of new cervical cancer diagnoses in Italy in 2024 is approximately 2,382[

1].

In line with other EU countries, Italy introduced HPV vaccinations free of charge for girls aged 11-12 years in 2008; an out-of-pocket payment could be required for older ages. Studies have confirmed over time the efficacy in preventing HPV infections, the safety and the cost/effectiveness of various vaccines authorised on the market [

2,

3,

4]. In the following years, vaccines have changed their composition, enriched with pathogenic strains and extending the possibility of prevention to other HPV-related cancers and diseases [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Increased coverage of HPV vaccines can significantly reduce the risk of other urogenital and head-neck cancers and benign lesions such as genital warts [

9,

10,

11]. Vaccinating patients with advanced cervical lesions may be an effective way to reduce recurrent H-SIL [

12] and prevent cervical cancer even though no therapeutic HPV vaccine has yet been approved for H-SIL and the use of lentiviral vaccines, although promising, is still in the preclinical phase[

13].

Our study aimed to determine how many women, with cervical cancer or high-grade dysplasia, were previously vaccinated and how many women had received the vaccine after these diagnoses.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted between October 15, 2024, and January 31, 2025, by the Health Technology Assessment Committee of Policlinico “G. Rodolico- San Marco”, a reference teaching and research hospital in Catania, Italy.

We collected information on women residing in the province of Catania, with a population of approximately one million inhabitants, who had a confirmed cytological or histological diagnosis of H-SIL or cervical cancer between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2020. We examined the number of women who had received the HPV vaccination. Patients who passed away before the introduction of HPV vaccination in Sicily (April 28, 2008) were excluded. Information on cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions was obtained from the Integrated Cancer Registry of Catania-Messina-Enna.

The data on cervical cancer and other cervical lesions were cross-checked between cases registered in the local vaccination registry of the Province of Catania and in the National Register of Causes of Death (RENCAM).

Patients were included if they met the following criteria: cytological or histological diagnosis of HPV-related cervical cancer or high-grade cervical lesions, residency in the province of Catania during the study period, and presence in the local vaccination registry. Cytological evaluations followed the Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology [

14], while biopsy samples were classified based on the WHO Classification of Tumours, as outlined by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Morphology was coded according to the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, third edition (ICDO-3)[

15]. Only cases with a positive cytological or histological examination uploaded to the database were included in the study.

For each patient, data were collected on diagnosis date, age at diagnosis, type and classification of the cancer or lesion, and tumour stage at the time of diagnosis.

Vaccination status was determined using the Provincial Vaccination Registry of Catania. A case verification agreement was established with the Prevention Department of the local health authority (Provincial Agency for Health of Catania - ASP 3). Data extracted included vaccine type, number of doses administered, and administration dates. We categorized our patients into fully vaccinated, if they received recommended doses of vaccine; partially vaccinated, if they received less than the recommended doses and not vaccinated if they received no doses. The tetravalent (4-serotype, 4vHPV) HPV vaccine was introduced in Catania in April 2008 and was later replaced by the nonavalent (9-serotype, 9vHPV) vaccine in September 2017. Patients' living status was verified using the RENCAM, updated as of December 31, 2023.

Diseases occurring 18 months after the first vaccine administration were considered to be vaccine failures.

Statistical Analysis

Data from the three sources were linked using a unique identification code assigned to each patient, ensuring anonymity and compliance with data protection regulations.

Statistical analyses were performed using R.

To describe vaccination status distribution, the following parameters were calculated: mean age at diagnosis, number of vaccine doses received at the time of diagnosis, number of vaccines administered post-diagnosis, mean and median time between diagnosis and vaccination, vaccination coverage among eligible patients, and the percentage of patients vaccinated after diagnosis.

Vaccination status and age were compared between subgroups based on tumour type, distinguishing between malignant tumours and H-SIL.

3. Results

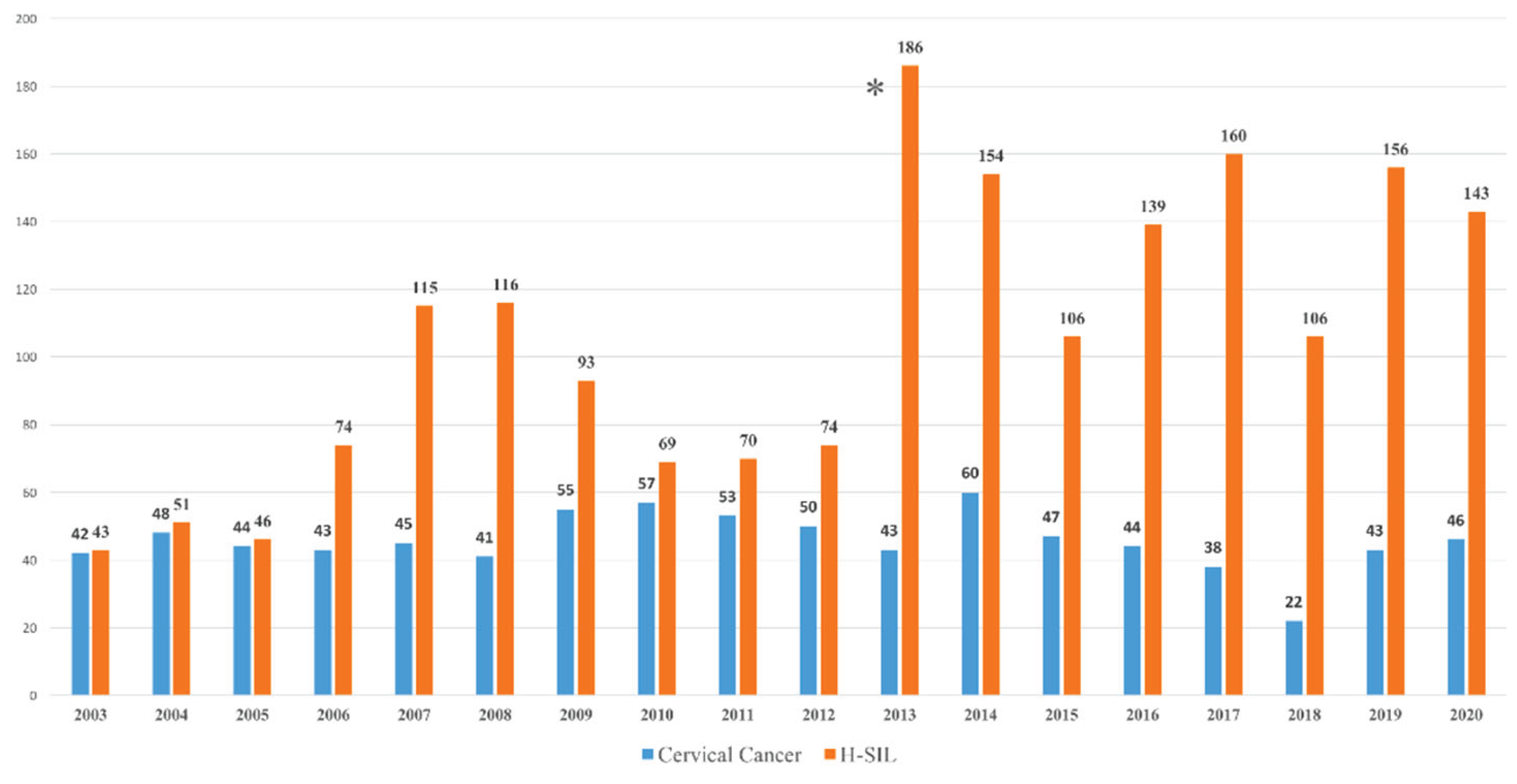

We analysed 2722 cases of women living in the province of Catania, Sicily, Italy diagnosed with cervical tumour or H-SIL between 2003 and 2020 (

Figure 1). As the first HPV vaccine was available in Catania in April 2008, 70 women, who had died before the vaccine became available, were excluded from the study. An increase in diagnosed H-SIL lesions has been observed since 2013, the year in which screening with HPV tests was introduced in our province.

The study included 2652 women (751 cervical cancer, 1901 H-SIL). Only 11,9 % had received at least one dose of the vaccine, while 88.1 percent had never been vaccinated. The average age of all women at the first vaccination dose was 34,9 years. Vaccination status of all cases, cervical cancer and H-SIL correlated by age at diagnosis and age at vaccination is detailed in

Table 1.

Among women with cervical cancer, 96% had never received any vaccine during their lives. None of the cases with cervical cancer had been vaccinated before diagnosis. The vaccinated women, with cervical cancer, were vaccinated after the diagnosis of the cervical lesion, with an average interval of 1872 days between the diagnosis and the first dose and only 3% had completed the expected cycle. The mean age at diagnosis of vaccinated women was 35.3 years old while the average age at vaccination was 39.5 years old.

Among women diagnosed with H-SIL 85% of them have never received a vaccination against HPV. The vast majority of patients were vaccinated after the diagnosis of cervical lesion; the average number of days between diagnosis and first vaccination dose was 1294, the median was 623 days. The average age at vaccination was 37.1 years.

We observed 10 H-SIL cases in women who were vaccinated. In six cases the time between vaccination and diagnosis was on average 7 years; in the other four cases, less than 15 months had elapsed between the completion of the vaccination cycle and the diagnosis of the disease. The woman’s average age at vaccination was 19.5 ± 4,1 years and the average age at diagnosis was 28 ± 4.1 years.

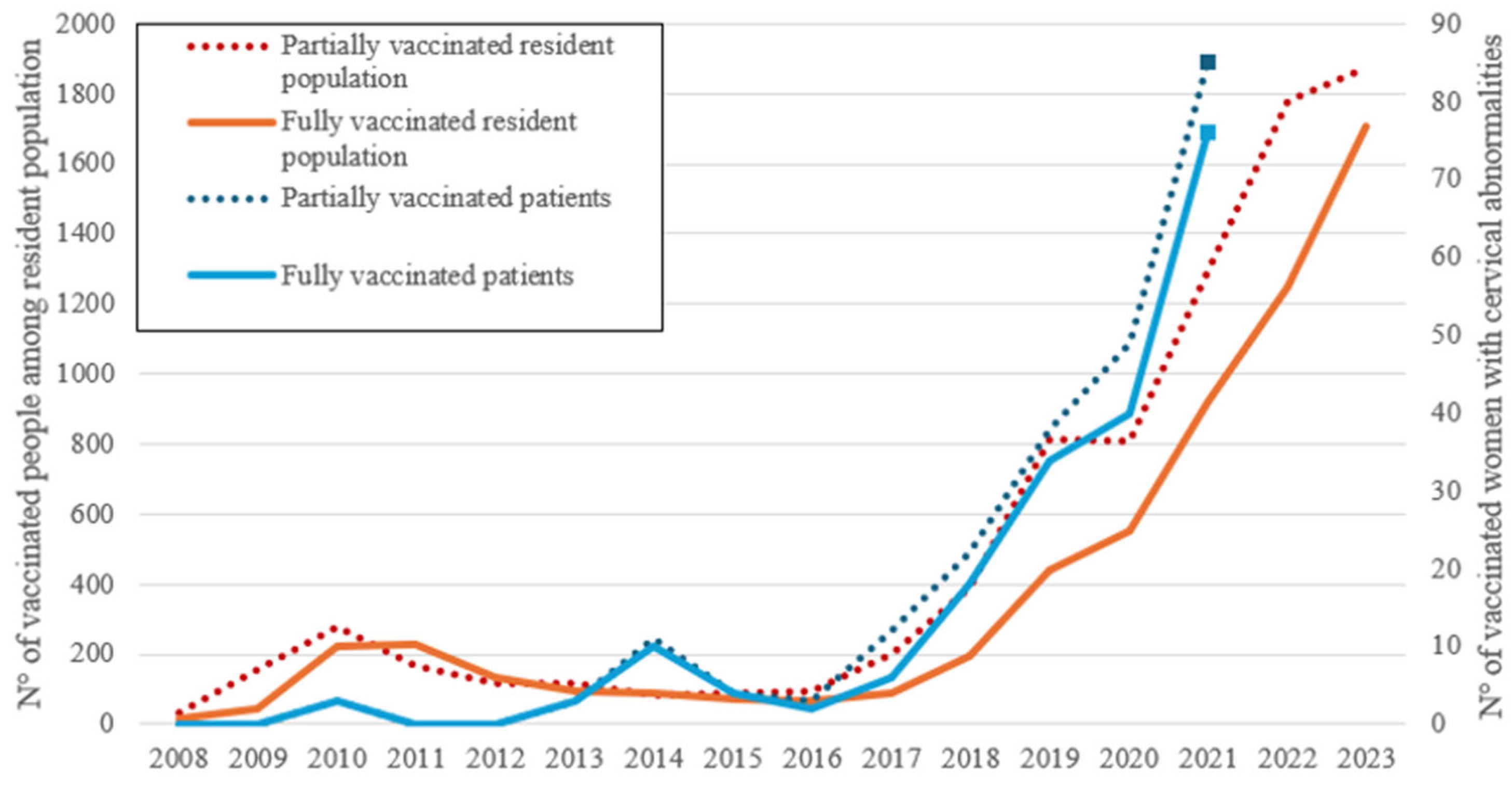

The number of women fully and partially vaccinated among the resident population of Catania and the number of fully and partially vaccinated women with cervical abnormalities is reported (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Our data confirm that the HPV vaccine is an effective but underutilized prevention tool to reduce the incidence of cervical and other HPV-related cancers[

16,

17]. The problems related to insufficient use of the HPV vaccine were analysed separately for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of HPV-related disease.

Primary Prevention / HPV Vaccines

In Italy, vaccines against HPV are offered free of charge to children aged 11 to 14. In our province, the HPV vaccine is free for birth cohorts from 1996 for females and from 2003 for males, who are not yet vaccinated. It is also offered in co-payment for other cohorts of females and males and in subjects considered at risk for pre-neoplastic lesions.

The model[

18] and observational data[

19] indicate that HPV vaccination can have a significant impact on HPV-related outcomes at a population-level, with a reduction in cervical cancer and incidence of H-SIL in young women. In our study we observed that, since the vaccine became available in 2008, none of the women who were vaccinated against HPV developed cancer until 2020, while

1575 high-grade lesions have been recorded among unvaccinated women.

The cases of H-SIL lesions recorded in women already vaccinated have arisen in subjects that, at the time of vaccination, were already beyond the age recommended by the guidelines. All of them received the 4-valent vaccine. Four cases developed lesions less than 15 months after administration of the vaccine, and so we do not consider this a vaccine’s failure because the infection was in all probability already present but undiagnosed. In the other six cases who developed an H-SIL lesion, the infection was presumably determined by virus subtypes not included in the vaccine.

Unfortunately, Italy is far from the objectives of the WHO and the European Community goals, unlike other nations [

20], and vaccination coverage remains suboptimal (69.3% of the girls and 57% of the boys born in 2007)[

21]. Vaccination coverage remains particularly low in our province[

22], with 26,7% of the female population born between 1996 and 2012 having received a full immunization and 54.6% at least one dose, while 24,4% of the males born between 2003 and 2012 are fully immunized and 40,5% received at least one dose of vaccine.

The Provincial Health Authority (ASP) of Catania began a significant prevention campaign in 2017, offering HPV vaccination to both male and female adolescents. A gradual increase in vaccinated women has been observed since 2018 (

Figure 2), and a peak was recorded during the period of the Covid-19 pandemic when a decrease in screening is likely to be matched by an increase in vaccinations. We do not know whether this was due to a greater sensitivity towards vaccinations or because it was considered the only preventive method available at that time. Women who had cervical abnormalities responded more easily to vaccine supply and reached peak earlier than the general population. The positive trend persist and is still present in the general population.

Adherence to vaccination has been enhanced by the publication of national guidelines in 2020.

The vaccination promotion campaign was subsequently accompanied by a catch-up vaccination program which will continue in the coming years. Catch-up HPV vaccination decreased the chance of all cervical abnormalities diagnosed during organized screening and provided an increased degree of herd protection for women who were not vaccinated [

23]. It will be necessary to increase vaccination coverage in males and to implement catch-up vaccination programs for young men that have an acceptable cost-effectiveness ratio [

24].

Secondary Prevention / HPV Screening

The long preclinical phase and the possibility to diagnose and remove precancerous lesions are the strengths of secondary prevention programs. The increase in vaccination coverage and the percentage of women being screened cover different segments of the population but are interrelated.

Recently published data show that no country in Europe had screening rates in line with or above the EU Commission's targets of 90%; however, a total of eight countries had screening participation rates below 70%, all of which used organized screening programs and HPV DNA as primary test or HPV DNA with cytology (PAP) for triage assays[

20].

Italy initiated cervical cancer screening programmes in 1989. Screening is performed every three years for people aged 24-64 years. The adherence to public health screening programs in 2023 was 41%, with lower values in the South and Islands (31%) compared to the North (52%) [

25]. Even if we add 20-30% of women who carry out the screening spontaneously and privately, the adherence is still insufficient to allow effective prevention at the population level.

In Catania, 50% of women aged 25-64 years have been screened as part of an organized program, while 27% have done so as individual preventive measures; 17% of women have never had a cervical screening, and 14% have done it for more than three years.

To reduce mortality, more efforts need to be made to screen all the population at risk and those who haven't been vaccinated. Similarly, women who don't want or can't do screening should be vaccinated.

The screening protocol will need to be modified due to the widespread use of HPV testing for screening, which allows us to lengthen the intervals of the procedure, and due to the introduction of the HPV immunization program.

Countries that have achieved optimal vaccination coverage could revisit HPV screening programs by extending the interval period and reducing costs. HPV-vaccinated women can expect a significant decrease in their lifetime risk of H-SIL, which would lead to less extensive screening for them[

26]. Further research is needed to determine intervals for re-screening HPV negative women[

27]. Today, there are increasingly accurate screening tests that reveal the presence of the virus both qualitatively and quantitatively. HPV vaccination could in fact modify some characteristics of the virus and generate false negatives or false positives in the screening of vaccinated cohorts [

28,

29]. Correct secondary prevention can only be carried out with kits that are validated for a safe diagnosis, an indispensable requirement for screening dispensed by the National Health System otherwise, the only safe possibility for prevention remains the vaccine.

The extension of HPV screening to men, where it is currently used for infertility diagnosis, could certainly help in the secondary prevention of HPV-related lesions and cancers.

Tertiary prevention / Adjuvant HPV vaccination

According to our study, the adjuvant vaccine is still not in use: only 15% of women with H-SIL lesions were given the HPV vaccine after the diagnosis of the lesion. An average of 592 days elapsed between diagnosis and the first administration of the vaccine.

The use of vaccination in the treatment of H-SIL lesions may reduce the circulation of the virus, contributing to the long-term reduction of the incidence of cervical cancer[

30]. When precancerous lesions are found, they are treated with excisional procedures. Full post-conization vaccination, with the 9vHPV, contributed to an additional reduction in the risk of recurrence and suggests a high adjuvant effect of the 9vHPV vaccine[

10,

11,

31]. The precise timing of HPV vaccination to reduce lesion recurrence remains unresolved[

32,

33].

Finally, it must be remembered that vaccination for people infected with HPV could also reduce the risk of developing a second primary cancer HPV related [

34,

35,

36,

37].

HPV Vaccine Communication Strategies

The percentage of vaccination coverage in our province is far from the WHO’s targets and shows that communication is not effective. It would not be explained otherwise why the possibility of preventing cancers (not only cervix) and genital warts, with a vaccine that is safe, effective, easy to administer, available, when offered free of charge, is not used. Primary vaccination is still too little carried out in our province, as well as screening and vaccination of women with H-SIL lesions. To increase coverage, action must be taken by diversifying the interventions.

Since it is known that the effectiveness of vaccination is greater in adolescents, it will be important to consider appropriate communication channels. Young people have access to a large amount of information through the Internet and social media. Information does not come from parents, teachers, or medical doctors but is absorbed by the environment and less often, by TV programs.

Considering that teenagers often do not like to talk about their health problems and sexual relationships, it could be useful to launch particular vaccination invitation campaigns by selecting an active influencer on social media as the spokesperson. Numerous studies have been carried out on the ability of social media to influence therapeutic choices [

38,

39,

40,

41] but also on the risks arising from incorrect information: the use of social media to promote correct choice would be a means to quickly reach a large number of users at low costs.

Vaccination banners, posted in the places most frequented by adolescents (schools, pubs, discos, gyms, bars) or in shops (clothing, telephone, electric cars for teenagers, motorbikes/scooters), can also be useful.

Lack of information from attending physicians, low confidence in the vaccine by gynaecologists, hesitation of women, and ignorance among adolescents and males must be overcome[

42].

The possible secondary damage due to conization in women

, including preterm delivery and low birth weight [

43,

44] and infertility in men[

45], must also be made known.

The practice of correctly vaccinating women with H-SIL lesions and the possibility of tertiary prevention, as a support for the treatment of cervical carcinoma, is not yet widespread. Since modern guidelines add to prophylactic vaccination also a post-intervention use of the vaccine, the scientific community should strive to publish and disseminate shared guidelines that define the most effective timing for the administration of the vaccine in subjects who have already had a cancer lesion. All general practitioners and gynaecologists should be carefully informed of this evidence.

A vaccine literacy organization to create an environment that supports individuals to find and use information and services on vaccines correctly, could help policymakers and individuals make informed decisions about vaccines [

46].

In contrast to cervical cancers, the global burden of cancers largely attributable to the HPV virus (vagina, vulva, anus, some head and neck cancer, as more recently recognized) is increasing. Since screening with HPV tests does not help as well as for the cervix in these tumours, vaccination in both sexes is an irreplaceable weapon for the possible reduction of the incidence of these tumours and their socio-economic burden[

47,

48].

5. Conclusions

The number of new cases of cervical cancer has shown a reduction in the last 30 years due to effective prevention (first screening and then vaccination) while the death rate was less reduced than in other cancers[

49,

50]. In particular, the 9vHPV vaccine has been shown to be effective even in the long-term period [

51].

Where prevention has not been carried out, the decline in incidence and mortality rates has not been observed[

52]. It should always be remembered that the vaccination must also be correctly performed in male adolescents to achieve a reduction in virus circulation and cover of any unvaccinated subjects through herd immunity and provide protection against HPV-related cancers.

A health policy that aims to achieve public health objectives can encourage catch-up actions while also exploring innovative strategies: vaccinate women in the hospital when the excision is carried out; ask for a vaccination certificate when registering at school (high school/university); engage influencers on social networks for the vaccination campaign; explain the possible damage of excision and discomfort associated with repeated interventions; ensure information to males.

General practitioners, paediatricians and gynaecologists are essential in informing people regarding vaccines and their potential benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rosalia Ragusa, Debora Fiorito and Vittorio Grieco; methodology, Vittorio Grieco, Rosalia Ragusa; software; formal analysis, Vittorio Grieco; investigation, Eleonora Irato, and Alessia Anna Di Prima; data curation, Vittorio Grieco, Chiara Chillari, and Alessia Anna Di Prima; writing—original draft preparation, Debora Fiorito, Vittorio Grieco and Rosalia Ragusa; writing—review and editing, Gabriele Giorgianni and Liliana Mereu; supervision, Rosalia Ragusa and Gabriele Giorgianni; project administration, Rosalia Ragusa. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Local Ethics Committee Catania 1 (Act of Resolution 2297/24 Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico di Catania; October 15, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as the present analysis was a secondary analysis of data, covered by the same consent statements and privacy provisions of the ASP that had previously been obtained.

Data Availability Statement

We are not permitted to share individual data. Aggregated-level data, in the form of counts, rates can only be shared upon express permission from the participating authorities. These data should be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- I numeri del cancro in Italia [Internet]. AIOM; 2024. Available on line: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024_NDC-web.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- La Torre, G.; de Waure, C.; Chiaradia, G.; Mannocci, A.; Capri, S.; Ricciardi, W. The Health Technology Assessment of bivalent HPV vaccine Cervarix® in Italy. Vaccine 2010, 28, 3379–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, P.; Panatto, D.; Dirodi, B.; Boccalini, S.; Gasparini, R. HPV vaccination and allocative efficiency: regional analysis of the costs and benefits with the bivalent AS04-adjuvanted vaccine, from the perspective of public health, for the prevention of cervical cancer and its pre-cancerous lesions. Farmeconomia. Health economics and therapeutic pathways 2012, 13, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccalini, S.; Ragusa, R.; Panatto, D.; Calabrò, G.E.; Cortesi, P.A.; Giorgianni, G.; Favaretti, C.; Bonanni, P.; Ricciardi, W.; de Waure, C. Health Technology Assessment of Vaccines in Italy: History and Review of Applications. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalik, K.; Tarney, C.; Han, J. Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination. Viruses 2021, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolratanakul, S.; Pitisuttithum, P. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Efficacy and Effectiveness against Cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sanjosé, S.; Serrano, B.; Tous, S.; Alejo, M.; Lloveras, B.; Quirós, B.; Clavero, O.; Vidal, A.; Ferrándiz-Pulido, C.; Pavón, M.Á.; et al. Burden of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Related Cancers Attributable to HPVs 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52 and 58. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 2018, 2, pky045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Xu, L. Human Papillomavirus-Related Cancer Vaccine Strategies. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, K.; Krause, D.; Xu, J.; Tsai, S.H.L.; Hage, C.; Weston, E.; Eke, A.; Levinson, K. Adjuvant Human Papillomavirus Vaccine to Reduce Recurrent Cervical Dysplasia in Unvaccinated Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2020, 135, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, K.; Misiek, M.; Chudecka-Głaz, A. Can Adjuvant HPV Vaccination Be Helpful in the Prevention of Persistent/Recurrent Cervical Dysplasia after Surgical Treatment?—A Literature Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, V.; Caruso, G.; Petrillo, M.; Kontopantelis, E.; Palaia, I.; Perniola, G.; Plotti, F.; Angioli, R.; Muzii, L.; Benedetti Panici, P.; et al. Adjuvant HPV Vaccination to Prevent Recurrent Cervical Dysplasia after Surgical Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.D.; Martí, C.; Torras, I.; Henere, C.; Munmany, M.; Marimon, L.; Saco, A.; Torné, A.; Ordi, J. HPV Vaccination as Adjuvant to Conization in Women with Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Study under Real-Life Conditions. Vaccines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douguet, L.; Fert, I.; Lopez, J.; Vesin, B.; Le Chevalier, F.; Moncoq, F.; Authié, P.; Nguyen, T.; Noirat, A.; Névo, F.; et al. Full eradication of pre-clinical human papilloma virus-induced tumors by a lentiviral vaccine. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2023, 15, e17723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology: Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes; Nayar, R. , Wilbur, D.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-11073-8. [Google Scholar]

- International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3).

- Adekanmbi, V.; Sokale, I.; Guo, F.; Ngo, J.; Hoang, T.N.; Hsu, C.D.; Oluyomi, A.; Berenson, A.B. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Human Papillomavirus–Related Cancer Rates. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2431807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, T.A.; Schiller, J.T. Human papillomavirus in cervical cancer and oropharyngeal cancer: One cause, two diseases. Cancer 2017, 123, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bondt, D.; Naslazi, E.; Jansen, E.; Kupets, R.; McCurdy, B.; Stogios, C.; de Kok, I.; Hontelez, J. Validating the predicted impact of HPV vaccination on HPV prevalence, cervical lesions, and cervical cancer: A systematic review of population level data and modelling studies. Gynecol Oncol 2025, 195, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcaro, M.; Castañon, A.; Ndlela, B.; Checchi, M.; Soldan, K.; Lopez-Bernal, J.; Elliss-Brookes, L.; Sasieni, P. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. The Lancet 2021, 398, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamousouli, E.; Sabale, U.; Valente, S.; Morosan, F.; Heuser, M.; Dodd, O.; Riley, D.; Heron, L.; Calabrò, G.E.; Agorastos, T.; et al. Readiness assessment for cervical cancer elimination and prevention of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers in Europe – are we winning the RACE? Expert Review of Vaccines 2025, 24, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coperture vaccinali al 31.12. 2023.

- Fiorito, D.; Ragusa, R.; Sgalambro, F.; Rapisarda, A.; Stefano, S.; Sarpietro, G.; Bruno, M.T.; Mereu, L. Cervical Lesions And HPV Vaccination Status: Epidemiological Analysis Of Population In Province Of Catania. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2025, 35, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martellucci, C.A.; Morettini, M.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Canfell, K.; Manzoli, L.; Flacco, M.E.; Palmer, M.; Rossi, P.G.; Martellucci, M.; Giacomini, G.; et al. Impact of a Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Program within Organized Cervical Cancer Screening: Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2022, 31, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J.J.M.; Westra, T.A.; Postma, M.J. Cost-effectiveness of a male catch-up human papillomavirus vaccination program in the Netherlands. Preventive Medicine Reports 2022, 28, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La diffusione degli screening oncologici in Italia nel 2023 | Osservatorio Nazionale Screening Available online:. Available online: https://www.osservatorionazionalescreening.it/content/la-diffusione-degli-screening-oncologici-italia-nel-2023 (accessed on Mar 7, 2025).

- Hoes, J.; King, A.J.; Berkhof, J.; de Melker, H.E. High vaccine effectiveness persists for ten years after HPV16/18 vaccination among young Dutch women. Vaccine 2023, 41, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi Rossi, P.; Carozzi, F.; Federici, A.; Ronco, G.; Zappa, M.; Franceschi, S.; Barca, A.; Barzon, L.; Baussano, I.; Berliri, C.; et al. Cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infection: Recommendations from a consensus conference. Preventive Medicine 2017, 98, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebolj, M.; Brentnall, A.R.; Cuschieri, K. Predictable changes in the accuracy of human papillomavirus tests after vaccination: review with implications for performance monitoring in cervical screening. Br J Cancer 2024, 130, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Cuschieri, K.; Bonde, J.; Schuurman, R.; Cocuzza, C.; Broeck, D.V.; Zhao, F.-H.; Rezhake, R.; Gultekin, M.; de Sanjosé, S.; et al. Criteria for second generation comparator tests in validation of novel HPV DNA tests for use in cervical cancer screening. Journal of Medical Virology 2024, 96, e29881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, F.L.; Kjaer, S.K.; Frederiksen, K.; Dehlendorff, C. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse after conization in relation to HPV vaccination status. International Journal of Cancer 2020, 147, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvořák, V.; Petráš, M.; Dvořák, V.; Lomozová, D.; Dlouhý, P.; Králová Lesná, I.; Pilka, R. Reduced risk of CIN2+ recurrence in women immunized with a 9-valent HPV vaccine post-excision: Retrospective cohort study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024, 20, 2343552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjalma, W.A.A.; Heerden, J. van; Wyngaert, T.V. den If prophylactic HPV vaccination is considered in a woman with CIN2+, what is the value and should it be given before or after the surgical treatment? European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2022, 269, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, B. Can prophylactic HPV vaccination reduce the recurrence of cervical lesions after surgery? Review and prospect. Infect Agents Cancer 2023, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, R.; Mahale, P.; Sonawane, K.; Sikora, A.G.; Chhatwal, J.; Schmeler, K.M.; Sigel, K.; Cantor, S.B.; Chiao, E.Y.; Deshmukh, A.A. Trends in Risks for Second Primary Cancers Associated With Index Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers. JAMA Network Open 2018, 1, e181999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, R.; Torrisi, A.; Di Prima, A.A.; Torrisi, A.A.; Ippolito, A.; Ferrante, M.; Madeddu, A.; Guardabasso, V. Cancer Prevention for Survivors: Incidence of Second Primary Cancers and Sex Differences—A Population-Based Study from an Italian Cancer Registry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.A.; Lai, L.L. Elevated risk of human papillomavirus-related second cancers in survivors of anal canal cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 4013–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Kleinerman, R.A.; Hildesheim, A.; Gilbert, E.S.; Storm, H.; Lynch, C.F.; Hall, P.; Langmark, F.; Pukkala, E.; Kaijser, M.; et al. Second Cancers After Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma of the Cervix. JCO 2009, 27, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Sun, L.; Xu, C.; Li, D. Characteristics of and User Engagement With Antivaping Posts on Instagram: Observational Study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 2021, 7, e29600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towne, J.; Suliman, Y.; Russell, K.A.; Stuparich, M.A.; Nahas, S.; Behbehani, S. Health Information in the Era of Social Media: An Analysis of the Nature and Accuracy of Posts Made by Public Facebook Pages for Patients with Endometriosis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2021, 28, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarron, E.; Larbi, D.; Dorronzoro, E.; Hasvold, P.E.; Wynn, R.; Årsand, E. Factors Engaging Users of Diabetes Social Media Channels on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram: Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e21204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, S.S.; Salici, N.S.; Baş, V.M.; Karaali, M.G.; Ergün, E.Z.; Avcı, E.B.; Tellal, E.S.; Yüksel, E.I.; Rasulova, G.; Erdil, D. Influence of Social Media and Internet on Treatment Decisions in Adult Female Acne Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual 2024, 14, e2024156–e2024156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Gianolio, L.; Edefonti, V.; Khaleghi Hashemian, D.; Casini, F.; Bergamaschi, F.; Sala, A.; Verduci, E.; Calcaterra, V.; Zuccotti, G.V.; et al. HPV Vaccination in Young Males: A Glimpse of Coverage, Parental Attitude and Need of Additional Information from Lombardy Region, Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgiou, M.; Koliopoulos, G.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Arbyn, M.; Prendiville, W.; Paraskevaidis, E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 2006, 367, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Kyrgiou, M.; Simoens, C.; Raifu, A.O.; Koliopoulos, G.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Prendiville, W.; Paraskevaidis, E. Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garolla, A.; Graziani, A.; Grande, G.; Ortolani, C.; Ferlin, A. HPV-related diseases in male patients: an underestimated conundrum. J Endocrinol Invest 2024, 47, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C.; Del Riccio, M.; Zanobini, P.; Biasio, R.L.; Bonanni, P.; Giorgetti, D.; Ferro, V.A.; Guazzini, A.; Maghrebi, O.; Lastrucci, V.; et al. Vaccination as a social practice: towards a definition of personal, community, population, and organizational vaccine literacy. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebanova, H.; Stoev, S.; Naseva, E.; Getova, V.; Wang, W.; Sabale, U.; Petrova, E. Economic Burden of Cervical Cancer in Bulgaria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Lai, C.-H.; Chien, L.; Pan, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-J.; Feng, C.; Chang, C.-J. Economic Burden of Cervical and Head and Neck Cancer in Taiwan from a Societal Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, N.; Aoki, D.; Sharma, D.N.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2021, 155, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjaer, S.K.; Falkenthal, T.E.H.; Sundström, K.; Munk, C.; Sture, T.; Bautista, O.; Rawat, S.; Luxembourg, A. Long-term effectiveness of the nine-valent human papillomavirus vaccine: Interim results after 12 years of follow-up in Scandinavian women. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024, 20, 2377903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, E. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Japan. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2024, 50, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).