Introduction

From ancient tragedy to contemporary algorithms, art has always invited us not only to see but to feel. The earliest systematic theory of art’s affective power comes from Aristotle’s Poetics (ca. 335 BCE/2006), which proposes that tragedy evokes pity and fear in order to purge them cathartically. Nearly two millennia later, Hume (1757/1987) argued that taste originates in sentiment. “Beauty is not a quality inherent in things themselves; it exists only in the mind that perceives them” (p. 144). Meanwhile, Baumgarten (1750) elevated feeling to a philosophical status by coining the term aesthetica as a “scientia cognitionis sensitivae” (Ertürk, 2016). During the eighteenth century, these intuitions crystallized into systematic frameworks. Burke (1757/1823) contrasted beauty with the sublime, observing the paradoxical pleasure of tragic representation “objects which in the reality would shock, are in tragical, and such like representations, the source of a very high species of pleasure” (p. 54). He traced this delight to sympathy itself, where pity and terror, though painful in direct experience, yield a peculiar form of pleasure when represented at a safe remove. Kant (1790/1987), while maintaining the distinction between the beautiful and the sublime, reconceived sublimity as involving what he called a “negative pleasure,” arising from an initial inhibition of the faculties that is transformed into admiration and respect (p. 98). By contrast, Kant held that disgust (Ekel) could never be integrated into aesthetic judgment: “there is only one kind of ugliness that cannot be presented in accordance with nature without obliterating all aesthetic liking … that ugliness which arouses disgust” (p. 180).

Building on these eighteenth-century accounts, contemporary neuroscience provided converging evidence that affective processes are central to aesthetic experience (Chatterjee, 2011; Freedberg & Gallese, 2007). Kawabata and Zeki (2004) found that perceived beauty of paintings positively correlated with activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), a region also implicated in emotional processing and reward evaluation (Chatterjee, 2011; OʼDoherty et al., 2001). Ishizu and Zeki (2011) further showed that the experience of ugliness engages the amygdala alongside the left somato-motor cortex, while images judged “sorrowfully beautiful” recruit the same mOFC area (Ishizu & Zeki, 2017). More recent evidence supports a parametric “beauty-coding” axis within the mOFC (field A1), independent of whether the stimulus is sensory or conceptual in nature (Zeki, 2019; Rasche et al., 2023). Recent evidence demonstrates that as ugliness intensifies, mOFC activity decreases while amygdala and insula responses increase, supporting the view that the mOFC represents beauty and ugliness along a single continuous dimension rather than through a separate “ugliness network” (Rasche et al., 2024). If artworks judged as ugly elicit amygdala and insula activity alongside reduced mOFC responses, then affective stimuli that reliably activate these same limbic circuits provide a useful tool to investigate how emotional states bias subsequent aesthetic judgments.

Crucially, functional MRI confirms that unpleasant images (from the International Affective Picture System, IAPS) reliably elicit activation of the bilateral amygdala, as well as responses in the hippocampus and cingulate cortex (Aldhafeeri et al., 2012). The amygdala can be engaged even when observers remain unaware of the eliciting stimulus: classic masked-face studies demonstrated robust amygdala responses to unseen threat cues (Morris et al., 1998; Whalen et al., 1998), and subliminal presentations can activate the amygdala via a rapid subcortical pulvinar route (Sato et al., 2019). Taken together, these findings suggest the existence of a neural pathway by which affective states can bias higher-order evaluations. Whether such mechanisms extend specifically to aesthetic judgments, however, remains unresolved: few studies have examined the effects of emotional priming on aesthetic appreciation, and those that have report contradictory findings.

Flexas et al. (2013) showed that artworks were rated as more likable when preceded by happy faces and less likable when preceded by disgusted ones. These effects emerged when primes were consciously perceived (300 ms), whereas at subliminal presentation (20 ms) only happy primes influenced ratings. By contrast, Era et al. (2015) reported that subliminal negative primes (17 ms) increased beauty ratings for abstract art and human bodies. The authors interpreted this paradoxical effect as a contrast mechanism, explicitly linking it to Burke’s and Kant’s philosophical paradox of the sublime. Eskine et al. (2012) found that inducing fear but not happiness prior to viewing abstract art elevated ratings of sublimity, echoing Burke’s emphasis on fear as central to the sublime. More recently, Gerger et al. (2019) compared two types of visual primes: emotional scenes from the IAPS database and faces with distinct emotional expressions. They found that positive stimuli increased liking, while fear and disgust reduced it. Crucially, these effects were not accompanied by prime-congruent electromyographic (EMG) responses, suggesting that priming in the aesthetic domain operates through top-down cognitive modulation rather than automatic emotional processing.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the impact of negative primes on aesthetic judgments depends on multiple interacting factors: prime awareness (SOA and masking), prime modality (faces vs. scenes), discrete emotion (fear vs. disgust), and target ambiguity (abstract vs. representational art). Under conscious conditions primes typically produce valence-congruent assimilation: for example, Flexas et al. (2013) found that happy primes increased liking and disgust primes decreased it. Gerger et al. (2019) further confirmed this assimilation pattern subliminally across both face and scene primes. By contrast, some priming and induction manipulations yield paradoxical outcomes: Era et al. (2015) reported that subliminal negative primes increased beauty ratings for both abstract art and human bodies, and Eskine et al. (2012) found that consciously inducing fear heightened ratings of sublimity in abstract art.

Despite valuable insights, these studies share important limitations. As Gerger et al. (2019) noted, target stimuli were rarely controlled for baseline liking or emotional content, raising the possibility that priming effects were confounded by pre-existing preferences. Era et al. (2015) controlled for static and dynamic features but not prior liking or emotionality. Flexas et al. (2013) used cropped paintings without content controls, and Eskine et al. (2012) used only five artworks, limiting generalizability. Finally, most experiments focused primarily on abstract art, leaving the role of priming across different artistic categories largely unexplored. These gaps underscore the need for a study that systematically controls baseline evaluations, incorporates a large and diverse stimulus set, and directly compares abstract, landscape, and portrait art under both conscious and preconscious priming conditions.

To account for the variability in affective priming results, it is useful to consider theoretical models of aesthetic processing. Leder et al.’s (2004) stage model proposes that aesthetic experience unfolds in a sequence, beginning with early perceptual analysis and culminating in higher-order evaluation. Within this framework, the affective state present at the onset of an aesthetic episode has disproportionate influence on subsequent judgments. The Affect Infusion Model (Forgas, 1995) further specifies how affect shapes cognition: positive affect broadens associative networks and promotes assimilation, whereas negative affect narrows attention and can produce contrast effects. Predictive processing accounts extend this reasoning by proposing that aesthetic liking is shaped by top-down schemas and prior expectations (Frascaroli et al., 2024). Because affective states also bias higher-level cognition including interpretation, judgment, decision-making, and reasoning (Blanchette & Richards, 2010; Flexas et al., 2013) it follows that the influence of primes will vary depending on when and how they interact with the unfolding aesthetic episode.

Another source of variability concerns the type of artwork being judged. Abstract paintings lack semantic anchors and are therefore especially susceptible to contextual and affective influences (Locher et al., 2008; Pihko et al., 2011), whereas portraits and landscapes may be more evolutionarily salient (Dutton, 2009). Neurophysiological studies indicate that aesthetic evaluation itself unfolds in stages: Cela-Conde et al. (2013) reported an early aesthetic appreciation phase at 500–750 ms, followed by default mode network involvement beginning around 1500 ms. To capture how these staged processes manifest behaviorally, eye-tracking offers a powerful window into aesthetic engagement. Studies show that low-level compositional features, such as symmetry and balance, guide initial fixations, whereas later exploration reflects higher-order interpretation and affective modulation (Locher et al., 2008; Wallraven et al., 2009; Nayak & Karmakar, 2019). Consistent with this, global scan-paths are associated with judgments of visual complexity, whereas aesthetically pleasing works tend to elicit more localized, focused fixations (Wallraven et al., 2009; Marin & Leder, 2022). As Gombrich famously argued, “art is incomplete without the perceptual and emotional involvement of the viewer” (Nayak & Karmakar, 2019), and eye-movement patterns provide a direct signature of this involvement. Yet despite their promise, very few studies have systematically combined manipulations of composition, emotion, and awareness with gaze metrics (Kaspar & König, 2012; Nayak & Karmakar, 2019). Thus, the role of affective priming in shaping visual exploration during art viewing remains largely unexplored.

Present Study

The present study examined how affective priming influences aesthetic appreciation, extending prior work (e.g., Flexas et al., 2013) by addressing key limitations in the literature. First, emotional primes were selected within the circumplex model of emotion (Russell, 1980), ensuring that both valence and arousal dimensions were taken into account. Specifically, unpleasant and neutral IAPS images were chosen based on normative ratings, following Aldhafeeri et al.’s (2012) criteria, which demonstrated that unpleasant IAPS reliably elicit bilateral amygdala activation. By contrasting unpleasant versus neutral primes rather than discrete emotions (e.g., disgust or fear), we sought to capture the broader impact of negative valence on aesthetic judgments. Second, and crucially, three types of paintings, portrait, landscape, and abstract, were included, allowing us to compare how different painting categories are differentially affected by priming. Third, awareness levels were systematically manipulated (50 ms preconscious vs. 1000 ms conscious) to test whether conscious processing is necessary for affective modulation, as suggested by recent findings (Gerger et al., 2019). Fourth, to reduce baseline confounds, participants’ emotional status (depression, anxiety) was measured and appropriately excluded. This step is consistent with Leder’s (2004) information-processing model, which emphasizes that the affective state at the beginning of an aesthetic experience is particularly important for downstream evaluative outcomes. Fifth, to avoid familiarity and mere-exposure effects, which have been shown to bias affective preference toward familiar stimuli (Leder et al., 2012), novel DALL E-generated paintings as targets were used. Finally, each painting was presented for 4 seconds while recording eye movements, allowing us to examine whether affective priming influences not only beauty ratings but also patterns of visual exploration.

Based on prior work and theoretical models, we hypothesize that: (i) Unpleasant IAPS primes will decrease beauty ratings compared to neutral primes, but primarily under conscious presentation (Flexas et al., 2013) (ii) Abstract paintings will show the largest rating drop due to their lack of semantic anchors (Pihko et al., 2011); (iii) Affective priming will manifest in distinct oculomotor patterns, with effects varying by both awareness level and painting type.

Methods

Participants and Pre-Processing

Participants

A total of 171 undergraduate students were recruited through social-media posts and a university-wide mailing list. They received partial course credit for completing the online screening phase. After providing electronic consent, participants confirmed normal or corrected-to-normal vision and completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996; Hisli, 1989) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988; Ulusoy et al., 1998). Those scoring BDI ≥ 16 or BAI ≥ 17 were excluded (n = 73). An additional 33 individuals were excluded for practical or eligibility reasons (e.g., professional involvement in the arts, residence outside commuting range for the laboratory session, self-reported psychiatric or neurological conditions, chronic illness, or current psychoactive substance use). The remaining 65 students (42 women, 23 men; aged 18–26) were invited to the laboratory for the second phase of the study. After providing written consent, they were randomly assigned to either the Conscious (1000 ms) or the Preconscious (50 ms) manipulation group.

Eye-Tracking and Pre-Processing

Eye-tracking quality was continuously monitored during acquisition. Calibration was repeated if the nine-point accuracy check exceeded 1°, ensuring precise alignment of gaze coordinates with screen locations. After data collection, offline preprocessing followed the two-stage protocol of Papenmeier et al. (2024). First, trials whose duration deviated by more than ±200 ms from the programmed 4,000 ms window were discarded. Second, a tracking ratio (percentage of valid gaze samples) was computed for each trial; those with ratios below 90% were excluded to prevent poor-quality epochs from biasing the results. Additional dataset-level criteria were applied offline: participants were excluded if overall data loss exceeded 40% or if blinks occupied more than 30% of recording time. This procedure removed only a small proportion of trials, and all aesthetic judgment data were retained. Based on these quality checks, 13 additional participants were excluded.

Final Sample

The final analyzed sample comprised 52 students (36 women, 16 men; aged 18–26), with 22 in the Conscious condition and 30 in the preconscious condition. All procedures were approved by the Adnan Menderes University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Ethics Committee and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials

AI-Generated Paintings

To avoid familiarity effects, AI-generated images were used instead of real artworks. All paintings were created using

DALL-E (OpenAI), which generates novel images from natural-language prompts. For each of three categories, portrait, abstract, and landscape, 80 unique images were initially generated (total = 240). The research team evaluated all images for clarity, resolution, and aesthetic plausibility, and selected the 40 best in each category, yielding a final set of 120 paintings (40 per category). Paintings were square (1024 × 1024 pixels) and presented in randomized order in both study phases. In the online first phase, participants were instructed to use a computer monitor for rating the 120 paintings. In the laboratory phase, a subset of 60 images (20 per category) was drawn from the pool and shown to all participants, ensuring balanced category representation while keeping the session manageable. Each image was presented twice once after a neutral prime and once after an unpleasant prime allowing within-subject comparisons of aesthetic ratings under different emotional contexts. The images used in both phases are provided in the

Supplementary Materials.

Emotional Prime Stimuli

Emotional priming images were drawn from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al., 2005). Following Aldhafeeri et al. (2012) selection criteria, 20 neutral and 20 unpleasant images were selected. Neutral set had a mean valence = 4.90 (SD = 0.30), mean arousal = 2.58 (SD = 0.36), while the unpleasant set had a mean valence = 1.98 (SD = 0.31), mean arousal = 6.33 (SD = 0.41). Each experimental block (neutral and unpleasant) contained 20 images, each shown three times in randomized order, yielding 60 trials per block. Detailed image codes and normative statistics are provided in the

Supplementary Materials.

Apparatus

The experiment was conducted in a controlled laboratory setting using a 27-inch LCD monitor (1920 x 1080 pixels, 120 Hz refresh rate). Stimuli were presented via SMI Experiment Center software, and eye movements were recorded binocularly at 120 Hz with an SMI RED-m remote eye tracker (SensoMotoric Instruments GmbH). Calibration was performed with a standard nine-point routine and repeated if mean error exceeded 1°. A post-experiment awareness screening task designed to assess recognition of the IAPS primes was implemented in PsychoPy (v2022), providing an objective measure of prime visibility and confirming the validity of group assignment.

Study Design

The experiment comprised two phases: an online baseline phase (Phase 1) and a laboratory-based priming phase (Phase 2). This design allowed us to first assess participants’ baseline aesthetic preferences and then test whether those preferences could be modulated by emotional priming under different levels of awareness. Phase 1 ensured unbiased baseline ratings, while Phase 2 introduced neutral or unpleasant primes (50 ms preconscious vs. 1000 ms conscious) before artwork presentation, with eye movements recorded during viewing.

Phase 1: Baseline Aesthetic Assessment and Screening

In Phase 1, participants completed an online screening via Google Forms. They viewed 120 AI-generated paintings (40 Portraits, 40 Abstracts, 40 Landscapes) presented in randomized order. For each image, participants rated aesthetic appeal on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not beautiful to 7 = very beautiful). These ratings provided within-subject baseline measures for later comparison.

Phase 2: Laboratory-Based Priming Experiment with Eye-Tracking

Two weeks later, eligible participants completed Phase 2 in the eye-tracking laboratory. This phase tested whether unpleasant vs. neutral primes (within-subject conditions) influenced aesthetic ratings of the same paintings from Phase 1, and whether these effects differed between awareness groups (Conscious vs. Preconscious). Each participant completed two experimental blocks one with neutral IAPS primes and one with unpleasant IAPS primes in counterbalanced order. Within each block, participants viewed and rated 60 paintings (20 Portraits, 20 Abstracts, 20 Landscapes), randomly selected from the original 120. Each painting was shown twice across the experiment: once after a neutral prime and once after an unpleasant prime. Both prime order and painting order were randomized. Importantly, participants were randomly assigned to one of two Awareness Groups: Conscious group (see Figure 1A): primes shown for 1000 ms, followed by a 1000 ms white-noise mask. Preconscious group (see Figure 1B): primes shown for 50 ms, followed by the same mask.

Eye movements were recorded throughout, but analyses focused on the 4000 ms painting-viewing period. At the end of Phase 2, participants completed a post-experiment awareness test in PsychoPy. They viewed all 40 primes used in the experiment (20 neutral, 20 unpleasant, each repeated once in random order) and indicated whether they had seen each image (“seen” vs. “not seen”). A chi-square analysis revealed that participants in the Conscious group recognized significantly more primes than those in the Preconscious group (p = .010), confirming the effectiveness of the awareness manipulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of trial sequences for the Conscious group (top-A) and the Preconscious (B) group (bottom). Each trial began with a fixation cross displayed for 1000 ms, followed by an IAPS prime. In the Conscious group (top), the prime (either Neutral or Unpleasant first) was presented for 1000 ms and was then immediately followed by a 1000 ms mask composed of colored white noise. In the preconscious group (bottom), the same IAPS primes were presented for 50 ms, followed by the identical 1000 ms white-noise mask. Following the prime and mask, in each trial one of the paintings randomly (type of painting was also randomized) (previously rated in Phase 1) was displayed for 4000 ms. Participants rated each painting’s aesthetic appeal using a 7-point Likert scale during this interval (Total 120 assessments). The question mark in the diagram indicates the moment when participants entered their aesthetic rating. Each painting appeared twice across the experiment: once following a Neutral prime and once following an Unpleasant prime in random order.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of trial sequences for the Conscious group (top-A) and the Preconscious (B) group (bottom). Each trial began with a fixation cross displayed for 1000 ms, followed by an IAPS prime. In the Conscious group (top), the prime (either Neutral or Unpleasant first) was presented for 1000 ms and was then immediately followed by a 1000 ms mask composed of colored white noise. In the preconscious group (bottom), the same IAPS primes were presented for 50 ms, followed by the identical 1000 ms white-noise mask. Following the prime and mask, in each trial one of the paintings randomly (type of painting was also randomized) (previously rated in Phase 1) was displayed for 4000 ms. Participants rated each painting’s aesthetic appeal using a 7-point Likert scale during this interval (Total 120 assessments). The question mark in the diagram indicates the moment when participants entered their aesthetic rating. Each painting appeared twice across the experiment: once following a Neutral prime and once following an Unpleasant prime in random order.

Behavioral Data Analysis

A 3 x 2 x 2 mixed factorial ANOVA was conducted using JASP (version 0.19.2; 2025) to examine how aesthetic evaluations were influenced by painting type, priming condition, and awareness group. Painting Type (Abstract, Portrait, Landscape) and Priming Condition (Neutral, Unpleasant) were within-subjects factors, and Awareness Group (Conscious vs. Preconscious) was a between-subjects factor. The dependent variable was the baseline corrected change in aesthetic rating, calculated by subtracting each painting’s baseline score from its corresponding rating after emotional priming. This baseline-corrected measure quantified how much priming shifted participants’ aesthetic preferences while controlling for initial ratings. Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon corrections were applied where the assumption of sphericity was violated. This analysis tested the hypothesis that aesthetic ratings would decrease following unpleasant relative to neutral priming, with a stronger effect in the Conscious group than in the preconscious group.

Statistical Analysis of Eye-Tracking Metrics

Eye-tracking data were analyzed (JASP; version 0.19.2; 2025) using a 3 (Painting Category: Abstract, Portrait, Landscape) x 2 (Priming Condition: Neutral, Unpleasant) x 2 (Awareness Group: Conscious, Preconscious) mixed factorial ANOVA, consistent with the design used for the behavioral data. Five primary metrics were assessed: fixation count, fixation duration, saccade count, saccade duration, and scan-path length. All metrics were extracted from the 4000 ms viewing window, beginning 200 ms after stimulus onset. Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon corrections were applied where the assumption of sphericity was violated.

Results

Behavioral Results

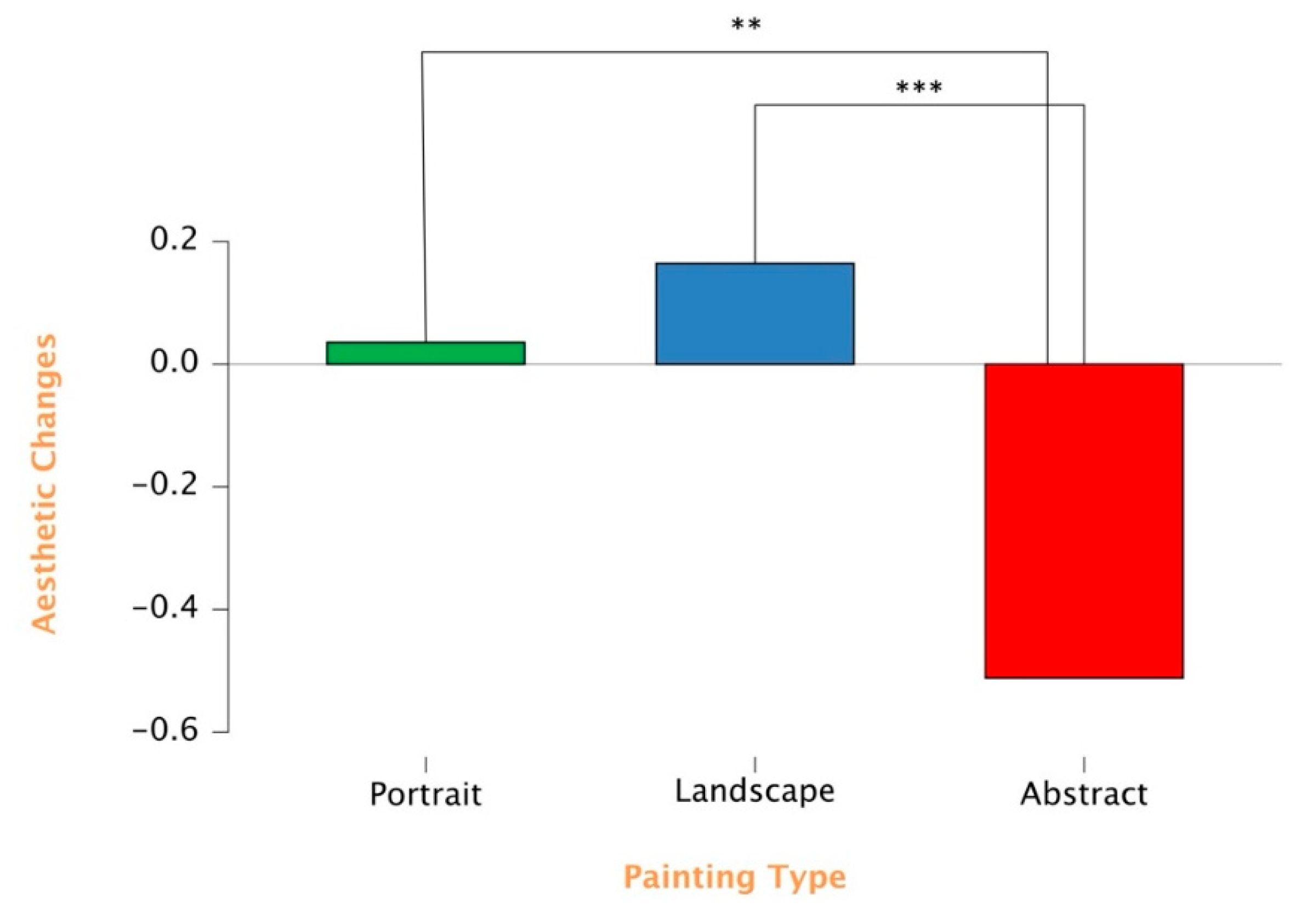

The analysis revealed a significant main effect of Painting Type, F(2, 100) = 11.17, p < .001, η²ₚ = .183, indicating that the degree of aesthetic change differed across painting categories (

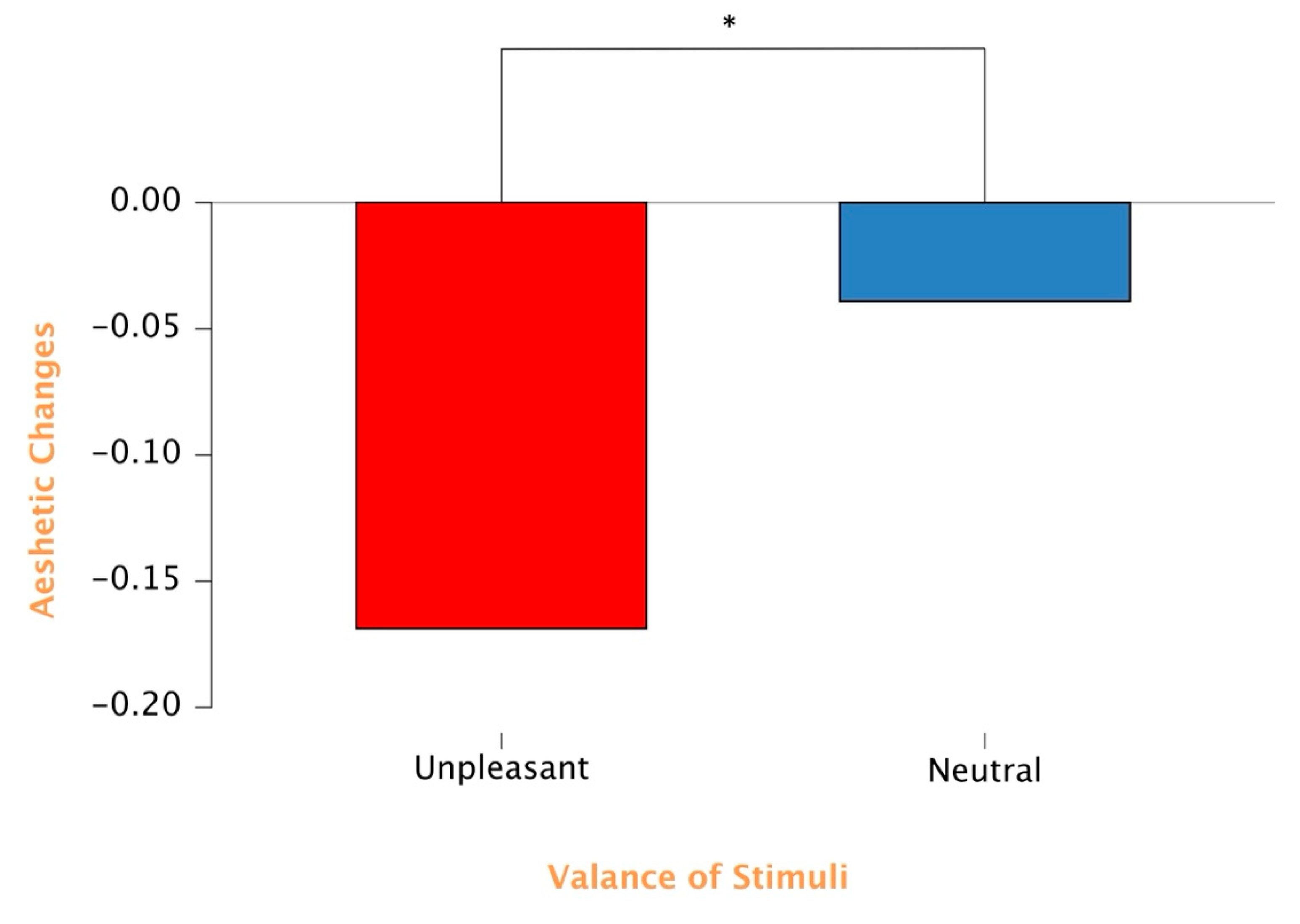

Figure 2). Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons showed that Abstract paintings differed significantly from both Landscapes (p < .001, mean difference = 0.663) and Portraits (p = .003, mean difference = 0.568). The comparison between Landscapes and Portraits did not reach significance (p > .05). These results suggest that Abstract paintings were more susceptible to shifts in aesthetic evaluation than the other categories. A significant main effect of Valence also emerged, F(1, 50) = 6.91, p = .011, η²ₚ = .121 (

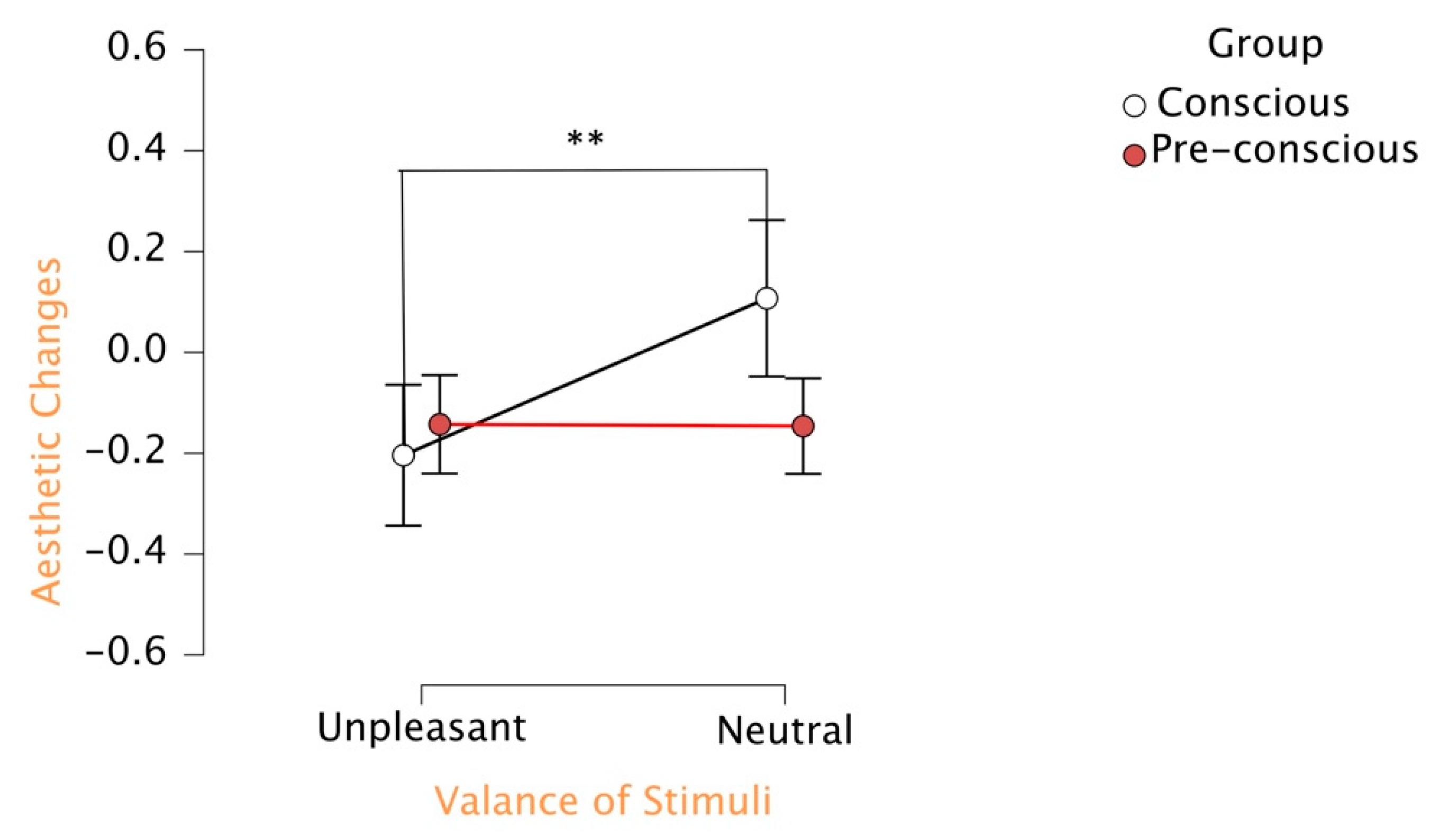

Figure 3), with lower aesthetic ratings following Unpleasant compared to Neutral priming (p = .011, mean difference =-0.154). Critically, a Valence x Group interaction was observed, F(1, 50) = 7.22, p = .010, η²ₚ = .126, indicating that priming effects differed between awareness groups (

Figure 4). Within the Conscious group, unpleasant primes produced significantly lower aesthetic-change scores than neutral primes (mean difference = –0.311, p = .006). In contrast, no effect of valence was observed in the preconscious group, and none of the between-group contrasts reached significance (all ps ≥ .862).

No significant main effect of Group was found, F(1, 50) = 0.12, p = .731, η²ₚ = .002. Likewise, the Painting Type x Group interaction, F(2, 100) = 1.08, p = .343, η²ₚ = .021, the Painting Type x Valence interaction, F(2, 100) = 1.13, p = .327, η²ₚ = .022, and the three-way interaction, F(2, 100) = 0.26, p = .769, η²ₚ = .005, were all non-significant.

Eye-Tracking Results

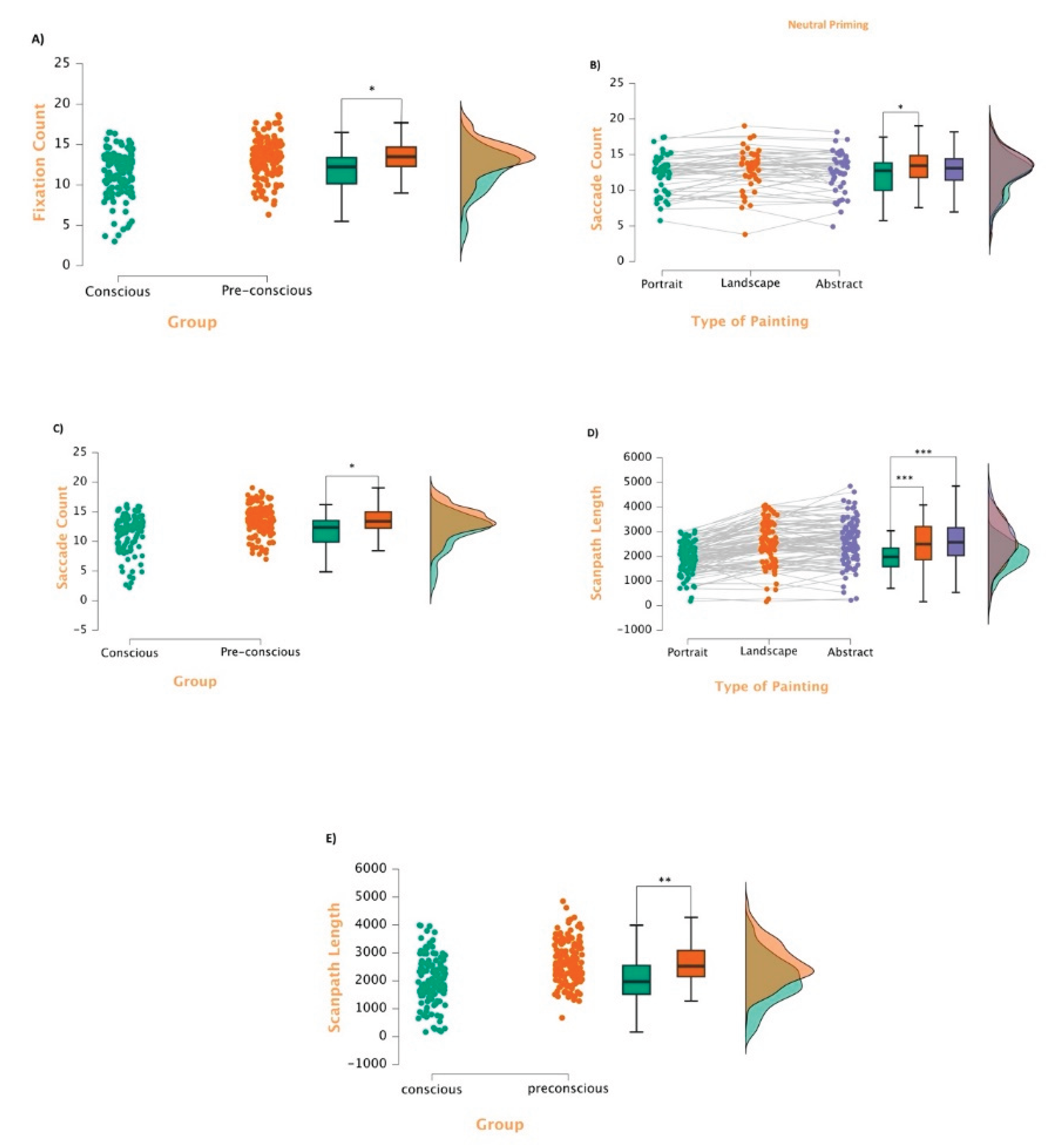

Fixation Count

The ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of Valence, F(1, 46) = 0.001, p = .970, η²ₚ < .001, or Painting Type, F(2, 92) = 0.05, p = .947, η²ₚ = .001. A significant Valence x Painting Type interaction was observed, F(2, 92) = 4.50, p = .014, η²ₚ = .089; however, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons did not identify reliable differences (all ps ≥ .719). Importantly, a significant between-subjects effect of Group emerged, F(1, 46) = 6.95, p = .011, η²ₚ = .131, with the Conscious group (M = –1.76, SE = 0.67) producing fewer fixations than the Preconscious group (

Figure 5A). No other interactions reached significance.

Fixation Duration Average

The ANOVA showed no significant main effect of Valence, F(1, 46) = 1.12, p = .295, η²ₚ = .024, and no main effect of Painting Type, F(1.69, 77.65) = 0.77, p = .465, η²ₚ = .017. The Valence x Painting Type interaction was also non-significant, F(1.37, 62.96) = 1.31, p = .274, η²ₚ = .028, as were all other interactions (ps > .20). The between-subjects effect of Group approached but did not reach significance, F(1, 46) = 3.72, p = .060, η²ₚ = .075.

Saccade Count

The ANOVA revealed no main effects of Valence, F(1, 46) = 0.01, p = .909, η²ₚ < .001, or Painting Type, F(2, 92) = 1.49, p = .231, η²ₚ = .031. A significant Valence x Painting Type interaction emerged, F(2, 92) = 5.47, p = .006, η²ₚ = .106. Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons showed that after neutral priming, Landscapes elicited significantly more saccades than Portraits (mean difference = –0.68, SE = 0.20, p = .023;

Figure 5B). No other pairwise comparisons were significant (p > .05).

A significant Group effect was also found, F(1, 46) = 6.40, p = .015, η²ₚ = .122, with the Conscious group producing fewer saccades than the Preconscious group (

Figure 5C). No other interactions reached significance.

Saccade Duration

The ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of Valence, F(1, 46) = 0.88, p = .353, η²ₚ = .019, or Painting Type, F(1.15, 52.72) = 1.83, p = .182, η²ₚ = .038. The Valence x Painting Type interaction was also non-significant, F(1.22, 56.13) = 2.05, p = .134, η²ₚ = .043. Neither Group nor its interactions reached significance (p > .24).

ScanPath Length

The ANOVA revealed a strong main effect of Painting Type, F(1.73, 79.67) = 70.53, p < .001, η²ₚ = .605 (

Figure 5D). Post hoc comparisons showed that Portraits elicited significantly shorter scanpaths than both Landscapes (mean difference = –557.11, p < .001) and Abstracts (mean difference = –648.99, p < .001), while Landscapes and Abstracts did not differ (mean difference = –91.89, p = .179). No main effect of Valence was observed, F(1, 46) = 0.74, p = .396, η²ₚ = .016, and no Valence x Painting Type interaction was found, F(2, 92) = 1.14, p = .325, η²ₚ = .024. A significant Group effect was observed, F(1, 46) = 10.07, p = .003, η²ₚ = .180, with the Conscious group showing shorter scanpaths than the Preconscious group (mean difference = –594.05, p = .003) (

Figure 5E).

Discussion

This study investigated whether unpleasant images used as primes influence aesthetic evaluations of paintings and whether these effects depend on awareness level and painting category. We also asked whether such effects manifest in oculomotor patterns during aesthetic viewing. Several behavioral findings emerged. First, abstract paintings were most susceptible to rating shifts compared to portraits and landscapes. Second, unpleasant primes reduced beauty ratings relative to neutral primes, but only under conscious processing (1000 ms). Eye-tracking analyses revealed that conscious processing, largely independent of prime valence, produced more constrained visual exploration characterized by fewer fixations, fewer saccades, and shorter scan paths. Beyond this awareness effect, painting type also shaped exploration, with portraits eliciting the most compact scan paths. A limited interaction further indicated that under neutral priming, landscapes elicited fewer saccades than portraits. Together, these findings demonstrate that affective modulation of aesthetic judgment requires conscious awareness, while both awareness level and painting type independently shape visual exploration strategies.

The Role of Awareness in Affective-Aesthetic Interactions

Unpleasant primes lowered aesthetic ratings only when consciously perceived, whereas no effect was observed in the preconscious condition. This indicates that affective information influences aesthetic judgment only when available for top-down cognitive integration, rather than through automatic, preconscious pathways. This conclusion extends Gerger et al. (2019) report of valence-congruent priming effects (fear and disgust reducing liking) under conditions of partial awareness, and complements Flexas et al. (2013), who showed stronger and more consistent effects for consciously perceived disgust primes than for masked ones. Our study advances these findings by showing that this awareness-dependent congruency generalizes beyond facial expressions to complex emotional scenes from the IAPS database.

These results must be interpreted in light of the current aesthetic models. Leder et al.’s (2004) stage model already posits multiple processing levels from perceptual analysis through explicit aesthetic judgment; our findings suggest that affective states can penetrate evaluative stages only when consciously available. The Affect Infusion Model (Forgas, 1995) likewise predicts that mood biases cognitive style, positive affect promoting broad, integrative processing and negative affect narrowing attention, but our results indicate that this bias operates only when affect is consciously accessible. Related frameworks propose that emotion participates as a first-order component of aesthetic evaluation (Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2014) by guiding valuation processes in prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices. In line with this, previous work shows that priming effects are mediated by top-down processes such as activation of emotionally congruent semantic networks (Greifeneder et al., 2011) and prefrontal engagement during evaluative modulation (Storbeck et al., 2006).

Our study built on evidence that unpleasant IAPS pictures reliably activate the bilateral amygdala (Aldhafeeri et al., 2012). Since amygdala responses scale primarily with arousal rather than valence (Anderson et al., 2003; Hamann et al., 2004; Fusar-Poli et al., 2009), we contrasted unpleasant versus neutral primes to isolate negative valence effects without reward-related confounds. Critically, Fusar-Poli et al.’s (2009) meta-analysis demonstrates stronger amygdala activation during explicit than implicit processing. Consistent with this, we found that unpleasant primes influenced beauty ratings only when consciously perceived, suggesting that awareness enables affective signals to shape aesthetic evaluations. While we cannot directly demonstrate the underlying neural mechanisms, our behavioral findings align with previous work.

Stimulus Ambiguity

The type of artwork played a crucial role. Abstract paintings were the most susceptible to negative shifts, revealing a gradient of vulnerability (from abstract to landscape to portrait) that inversely correlates with semantic anchoring and representational clarity. Abstract paintings, lacking semantic anchors, are especially vulnerable to contextual and affective influences (Locher et al., 2008; Pihko et al., 2011), forcing greater reliance on internal states that, when negatively primed, skew evaluations downward. This aligns with previous findings that negative primes reduce liking for abstract art (Flexas et al., 2013; Gerger et al., 2019).

One likely reason for abstract art’s heightened vulnerability lies in its lower comprehensibility. Leder et al. (2004, 2012) showed that ease of cognitive mastering is central to aesthetic pleasure, yet abstract works consistently receive lower comprehension ratings than representational art. As Silvia (2005) emphasized, when artworks are difficult to interpret, aesthetic appraisals become more variable and dependent on transient affective states, magnifying priming effects.

Neurobiologically, this pattern might reflect differential processing pathways. While portraits and landscapes engage specialized systems (Kanwisher et al., 1997; Epstein & Kanwisher, 1998) that provide perceptual stability, abstract art may instead rely on context-sensitive coupling between visual areas and medial frontal evaluative circuits (Rasche et al., 2023; Ishizu & Zeki, 2011). This architectural difference may explain why portraits and landscapes, which are more prototypical and evolutionarily salient (Dutton, 2009), are relatively resistant to affective contamination, while abstract art remains more vulnerable.

Absence of Contrast Effects

Unlike some previous studies that reported contrast effects, Era et al. (2015) found that subliminal negative primes (17 ms) increased beauty ratings for abstract images and bodies. Meanwhile, Eskine et al. (2012) showed that fear-inducing clips elevated sublimity ratings. However, our preconscious unpleasant primes produced no significant effects. These discrepancies likely reflect methodological and conceptual differences. Methodologically, our 50-ms primes exceeded Era’s 17-ms duration, potentially altering processing dynamics. Conceptually, Eskine measured sublimity (associated with awe and transcendence) rather than beauty, and both studies specifically targeted fear, a discrete emotion theorized by Burke (1757) to enhance aesthetic pleasure when experienced safely. By contrast, our study employed unpleasant IAPS images defined broadly by negative valence and high arousal, rather than a specific fear induction. Thus, while our results do not support general beauty enhancement through negative affect, they cannot directly refute Burke’s fear–sublime relationship. As Gerger et al. (2019) noted, contrast effects may require very specific conditions—such as extremely brief, high-arousal primes or affect misattribution. Despite confirmed effective masking in our study, preconscious affect was neither misattributed nor sufficiently strong to modulate beauty judgments.

Oculomotor Patterns and Visual Exploration

Our eye-tracking results revealed a dissociation between perceptual sampling and aesthetic evaluation. In the conscious group, participants showed fewer fixations and saccades and shorter scan paths, independent of prime valence, indicating that awareness itself, not emotional content, shaped viewing strategy. Reduced oculomotor activity has long been linked to constrained search (Holmqvist et al., 2011; Phillips & Edelman, 2008), and in art contexts, tighter gaze patterns are associated with aesthetic distance and focused engagement (Marin & Leder, 2022). The absence of valence effects on eye movements, despite clear effects on beauty ratings, challenges fluency-based models predicting that visual ease and aesthetic pleasure covary (Reber et al., 2004).

Stimulus category also strongly guided gaze patterns. Consistent with Papenmeier et al.’s (2024) finding that bottom-up visual features override framing labels, our data showed robust painting-type effects: portraits produced shorter scanpaths due to facial anchors (Locher & Nodine, 1987; Henderson & Hayes, 2018), while abstract works elicited longer paths, confirming that abstraction expands exploration (Pihko et al., 2011; Zangemeister et al., 1995). The Valence x Painting Type interaction (landscapes under unpleasant priming elicited more saccades than under neutral) aligns with Kaspar and König (2012) who suggesting that negative affect can increase exploratory viewing behavior, particularly in studies where emotional context shapes eye movements. This may reflect saliency dynamics, where salient features increase scanpath agreement (Schütz et al., 2011) and unpleasant primes heighten subsequent stimulus salience, encouraging greater exploration.

Limitations, Future Directions and Conclusion

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, we did not directly assess participants’ arousal or valence responses to the paintings. Berlyne’s (1974) model predicts an inverted-U relation between arousal and pleasure, but contemporary evidence is mixed and context-dependent (Leder et al., 2012). Future research should incorporate direct arousal and valence ratings to clarify how stimulus-driven arousal interacts with priming.Second, AI-generated stimuli minimized familiarity effects but raise ecological validity concerns. According to Leder et al. (2004), art classification is the first stage of processing. In other words, without recognizing stimuli as “art,” viewers may rely on low-level features and incidental affect rather than deeper aesthetic processing. Future studies should explicitly assess whether participants classify AI-generated images as artworks.

Two additional limitations warrant discussion. First, baseline ratings were collected online using participants’ own computer screens, introducing variability in display quality and viewing conditions. Although our within-subject analyses, which compared change scores between baseline and primed ratings, help control for this variability, it remains a factor to consider when interpreting the results. Second, our awareness terminology requires clarification. We labeled 50-ms masked primes as preconscious, meaning these affective stimuli were not consciously perceived during presentation but could potentially become accessible under different conditions, following research showing masked affective faces can bias evaluations without awareness (Murphy & Zajonc, 1993) and that unconscious processes influence higher-order cognition (Bargh & Morsella, 2008; Horga & Maia, 2012). Thus, preconscious indicates a transitional state, outside immediate awareness but not permanently inaccessible, while conscious refers to our 1000-ms primes.

Finally, this study was not a direct replication of earlier priming research (e.g., Gerger et al., 2019; Flexas et al., 2013; Era et al., 2015), but rather an extension that simultaneously examined awareness and painting type. We confirmed that consciously presented unpleasant primes reduce beauty ratings. Eye-tracking revealed that awareness and painting type, rather than prime valence, shape visual exploration. Using AI-generated images raises the question of whether viewers will classify them as art. Yet, their unfamiliarity avoids the mere-exposure effect, making them well suited for controlled experimentation. Taken together, the present study demonstrates that awareness critically gates the influence of emotion on aesthetic judgment and underscores the importance of considering both stimulus category and methodological innovation in future aesthetics research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

E.T.: Methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft preparation, Writing – review & editing, conceptualization, data acquisition. F.E.K: Methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft preparation, Writing – review & editing, conceptualization, data acquisition, supervision, project management. A.G.: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, formal analysis, supervision, original draft preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aldhafeeri, F. M., Mackenzie, I., Kay, T., Alghamdi, J., & Sluming, V. (2012). Regional brain responses to pleasant and unpleasant IAPS pictures: Different networks. Neuroscience Letters, 512(2), 94-98. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. K., Christoff, K., Stappen, I., Panitz, D., Ghahremani, D. G., Glover, G., ... & Sobel, N. (2003). Dissociated neural representations of intensity and valence in human olfaction. Nature Neuroscience, 6(2), 196-202. [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. (2006). Poetics (J. Sachs, Trans.). Focus Philosophical Library, Pullins Press.

- Bargh, J. A., & Morsella, E. (2008). The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 73-79. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893-897. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed.). The Psychological Corporation.

- Berlyne, D. E. (1974). The new experimental aesthetics. In D. E. Berlyne (Ed.), Studies in the New Experimental Aesthetics (pp. 1-25). Hemisphere.

- Blanchette, I., & Richards, A. (2010). The influence of affect on higher level cognition: A review of research on interpretation, judgement, decision making and reasoning. Cognition & Emotion, 24(4), 561-595.

- Burke, E. (1823). A philosophical inquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful (2nd ed.). Thomas Tegg. (Original work published 1757).

- Cela-Conde, C. J., García-Prieto, J., Ramasco, J. J., Mirasso, C. R., Bajo, R., Munar, E., ... & Maestú, F. (2013). Dynamics of brain networks in the aesthetic appreciation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(supplement_2), 10454-10461. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. (2011). Neuroaesthetics: A coming of age story. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(1), 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A., & Vartanian, O. (2014). Neuroaesthetics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 370-375. [CrossRef]

- Dutton, D. (2009). The art instinct: Beauty, pleasure, & human evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Epstein, R., & Kanwisher, N. (1998). A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Nature, 392(6676), 598-601. [CrossRef]

- Era, V., Candidi, M., & Aglioti, S. M. (2015). Subliminal presentation of emotionally negative vs positive primes increases the perceived beauty of target stimuli. Experimental Brain Research, 233(11), 3271-3281. [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, N. (2016). AG Baumgarten’da duyusal bilginin bilimi olarak estetik. Ulakbilge Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 4(7), 117-128.

- Eskine, K. J., Kacinik, N. A., & Prinz, J. J. (2012). Stirring images: Fear, not happiness or arousal, makes art more sublime. Emotion, 12(5), 1071-1074. [CrossRef]

- Flexas, A., Rosselló, J., Christensen, J. F., Nadal, M., Olivera La Rosa, A., & Munar, E. (2013). Affective priming using facial expressions modulates liking for abstract art. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e80154. [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 39-66. [CrossRef]

- Frascaroli, J., Leder, H., Brattico, E., & Van de Cruys, S. (2024). Aesthetics and predictive processing: Grounds and prospects of a fruitful encounter. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 379(1895), 20220410. [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, D., & Gallese, V. (2007). Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(5), 197-203. [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, P., Placentino, A., Carletti, F., Landi, P., Allen, P., Surguladze, S., ... & Politi, P. (2009). Functional atlas of emotional faces processing: A voxel-based meta-analysis of 105 functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 34(6), 418-432. [CrossRef]

- Gerger, G., Pelowski, M., & Ishizu, T. (2019). Does priming negative emotions really contribute to more positive aesthetic judgments? A comparative study of emotion priming paradigms using emotional faces versus emotional scenes and multiple negative emotions with fEMG. Emotion, 19(8), 1396-1413. [CrossRef]

- Greifeneder, R., Bless, H., & Pham, M. T. (2011). When do people rely on affective and cognitive feelings in judgment? A review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 107-141. [CrossRef]

- Hamann, S., Herman, R. A., Nolan, C. L., & Wallen, K. (2004). Men and women differ in amygdala response to visual sexual stimuli. Nature Neuroscience, 7(4), 411-416. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. M., & Hayes, T. R. (2018). Meaning guides attention in real-world scene images: Evidence from eye movements and meaning maps. Journal of Vision, 18(6), 10. [CrossRef]

- Hisli, N. (1989). Beck depresyon envanterinin universite ogrencileri icin gecerliligi, guvenilirligi [A reliability and validity study of Beck Depression Inventory in a university student sample]. Journal of Psychology, 7, 3-13.

- Holmqvist, K., Nyström, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & Van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford University Press.

- Horga, G., & Maia, T. V. (2012). Conscious and unconscious processes in cognitive control: A theoretical perspective and a novel empirical approach. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 199. [CrossRef]

- Hume, D. (1987). Of the standard of taste. In E. F. Miller (Ed.), Essays, moral, political, and literary (rev. ed., pp. 226–249). Liberty Fund. (Original work published 1757).

- Ishizu, T., & Zeki, S. (2011). Toward a brain-based theory of beauty. PLoS ONE, 6(7), e21852. [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, T., & Zeki, S. (2017). The experience of beauty derived from sorrow. Human Brain Mapping, 38(8), 4185-4200. [CrossRef]

- Kanwisher, N., McDermott, J., & Chun, M. M. (1997). The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. Journal of Neuroscience, 17(11), 4302-4311. [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, K., & König, P. (2012). Emotions and personality traits as high-level factors in visual attention: A review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 321. [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, H., & Zeki, S. (2004). Neural correlates of beauty. Journal of Neurophysiology, 91(4), 1699-1705. [CrossRef]

- Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (2005). International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual (pp. A-8). NIMH, Center for the Study of Emotion & Attention.

- Leder, H., Belke, B., Oeberst, A., & Augustin, D. (2004). A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. British Journal of Psychology, 95(4), 489-508. [CrossRef]

- Leder, H., Gerger, G., Dressler, S. G., & Schabmann, A. (2012). How art is appreciated. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(1), 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Locher, P., Krupinski, E. A., Mello-Thoms, C., & Nodine, C. F. (2008). Visual interest in pictorial art during an aesthetic experience. Spatial Vision, 21(1), 55-77. [CrossRef]

- Locher, P. J. , & Nodine, C. F. (1987). Symmetry catches the eye. In J. K. O’Regan & A. Lévy-Schoen (Eds.), Eye movements from physiology to cognition (pp. 353-361). Elsevier.

- Marin, M. M., & Leder, H. (2022). Gaze patterns reveal aesthetic distance while viewing art. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1514(1), 155-165. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J. S., Öhman, A., & Dolan, R. J. (1998). Conscious and unconscious emotional learning in the human amygdala. Nature, 393(6684), 467-470. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S. T., & Zajonc, R. B. (1993). Affect, cognition, and awareness: Affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 723-739. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B. K., & Karmakar, S. (2019). A review of eye tracking studies related to visual aesthetic experience: A bottom-up approach. In A. Chakrabarti (Ed.), Research into Design for a Connected World: Proceedings of ICoRD 2019 Volume 2(pp. 391-403). Springer.

- O’Doherty, J., Kringelbach, M. L., Rolls, E. T., Hornak, J., & Andrews, C. (2001). Abstract reward and punishment representations in the human orbitofrontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 4(1), 95-102. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. (2024). DALL-E 2. https://openai.com/index/dall-e-2/.

- Papenmeier, F., Dagit, G., Wagner, C., & Schwan, S. (2024). Is it art? Effects of framing images as art versus non-art on gaze behavior and aesthetic judgments. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 18(4), 642-656. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. H., & Edelman, J. A. (2008). The dependence of visual scanning performance on saccade, fixation, and perceptual metrics. Vision Research, 48(7), 926-936. [CrossRef]

- Pihko, E., Virtanen, A., Saarinen, V. M., Pannasch, S., Hirvenkari, L., Tossavainen, T., ... & Hari, R. (2011). Experiencing art: The influence of expertise and painting abstraction level. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 5, 94. [CrossRef]

- Rasche, S. E., Beyh, A., Paolini, M., & Zeki, S. (2023). The neural determinants of abstract beauty. European Journal of Neuroscience, 57(4), 633-645. [CrossRef]

- Rasche, S. E., Beyh, A., Paolini, M., & Zeki, S. (2024). Neural correlates of the experience of ugliness. European Journal of Neuroscience, 60(7), 5671-5679. [CrossRef]

- Reber, R., Schwarz, N., & Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 364-382. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161-1178. [CrossRef]

- Sato, W., Kochiyama, T., Minemoto, K., Sawada, R., & Fushiki, T. (2019). Amygdala activation during unconscious visual processing of food. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 7277. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, A. C., Braun, D. I., & Gegenfurtner, K. R. (2011). Eye movements and perception: A selective review. Journal of Vision, 11(5), 9. [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J. (2005). Cognitive appraisals and interest in visual art: Exploring an appraisal theory of aesthetic emotions. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 23(2), 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Storbeck, J., Robinson, M. D., & McCourt, M. E. (2006). Semantic processing precedes affect retrieval: The neurological case for cognitive primacy in visual processing. Review of General Psychology, 10(1), 41-55. [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, M., Sahin, N. H., & Erkmen, H. (1998). Turkish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory: Psychometric properties. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 12(2), 163–172.

- Wallraven, C. , Cunningham, D. W., Rigau, J., Feixas, M., & Sbert, M. (2009, May). Aesthetic appraisal of art: From eye movements to computers. In Computational Aesthetics 2009: Eurographics Workshop on Computational Aesthetics in Graphics, Visualization and Imaging (pp. 137-144). Eurographics.

- Whalen, P. J., Rauch, S. L., Etcoff, N. L., McInerney, S. C., Lee, M. B., & Jenike, M. A. (1998). Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(1), 411-418. [CrossRef]

- Zangemeister, W. H., Sherman, K., & Stark, L. (1995). Evidence for a global scanpath strategy in viewing abstract compared with realistic images. Neuropsychologia, 33(8), 1009-1025. [CrossRef]

- Zeki, S. (2019). Notes towards a (neurobiological) definition of beauty. Gestalt Theory, 41(2), 107-112. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).