Submitted:

26 July 2024

Posted:

29 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Features

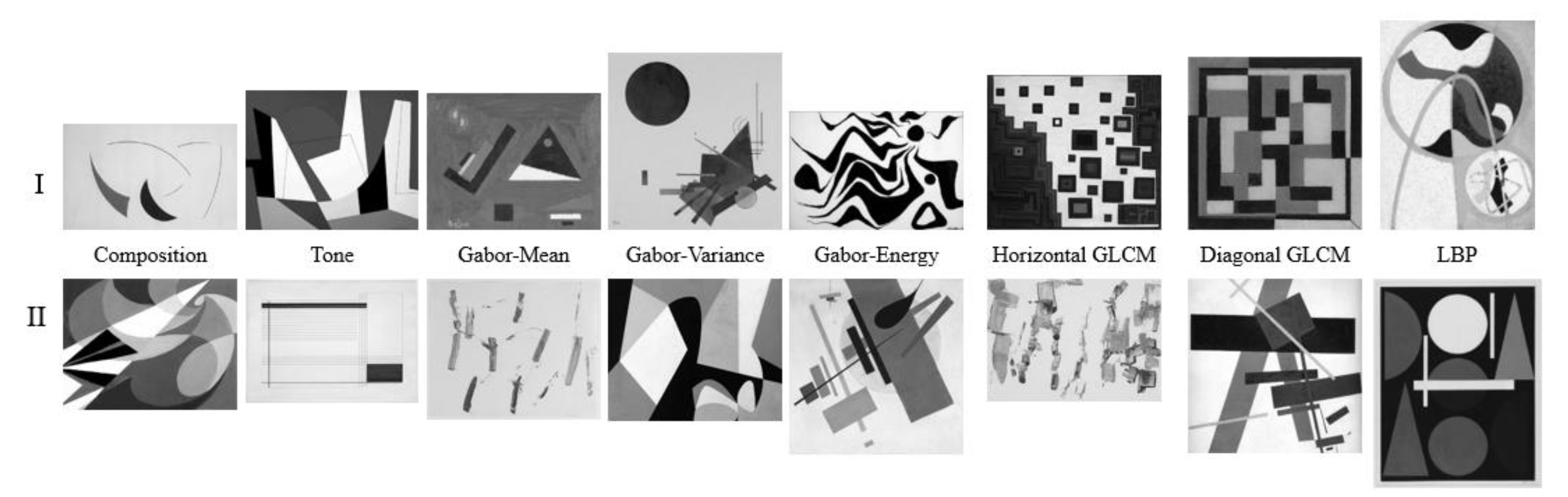

2.1.1. Composition

2.1.2. Tone

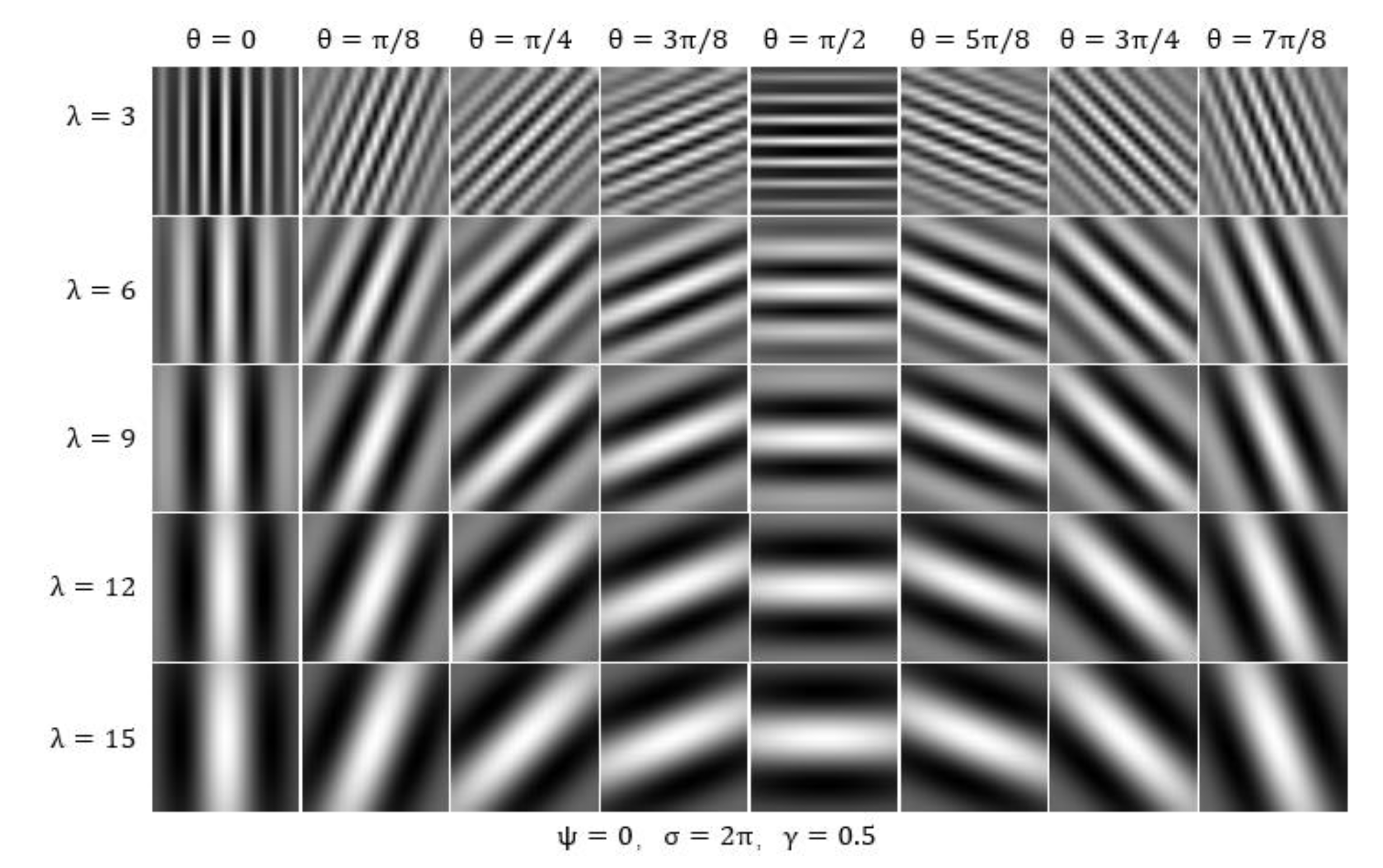

2.1.3. Global Texture Features

2.1.4. Local Texture Features

Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix (GLCM)

Local Binary Pattern (LBP)

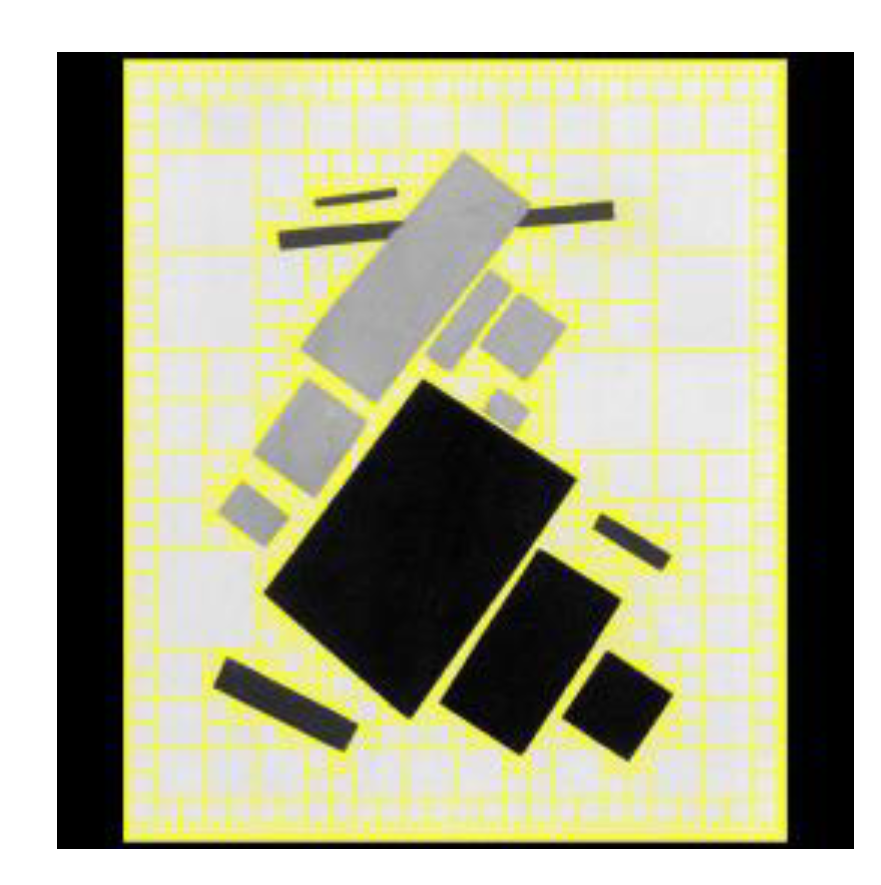

2.2. Stimulus

2.3. EEG and ERP

2.4. Participants

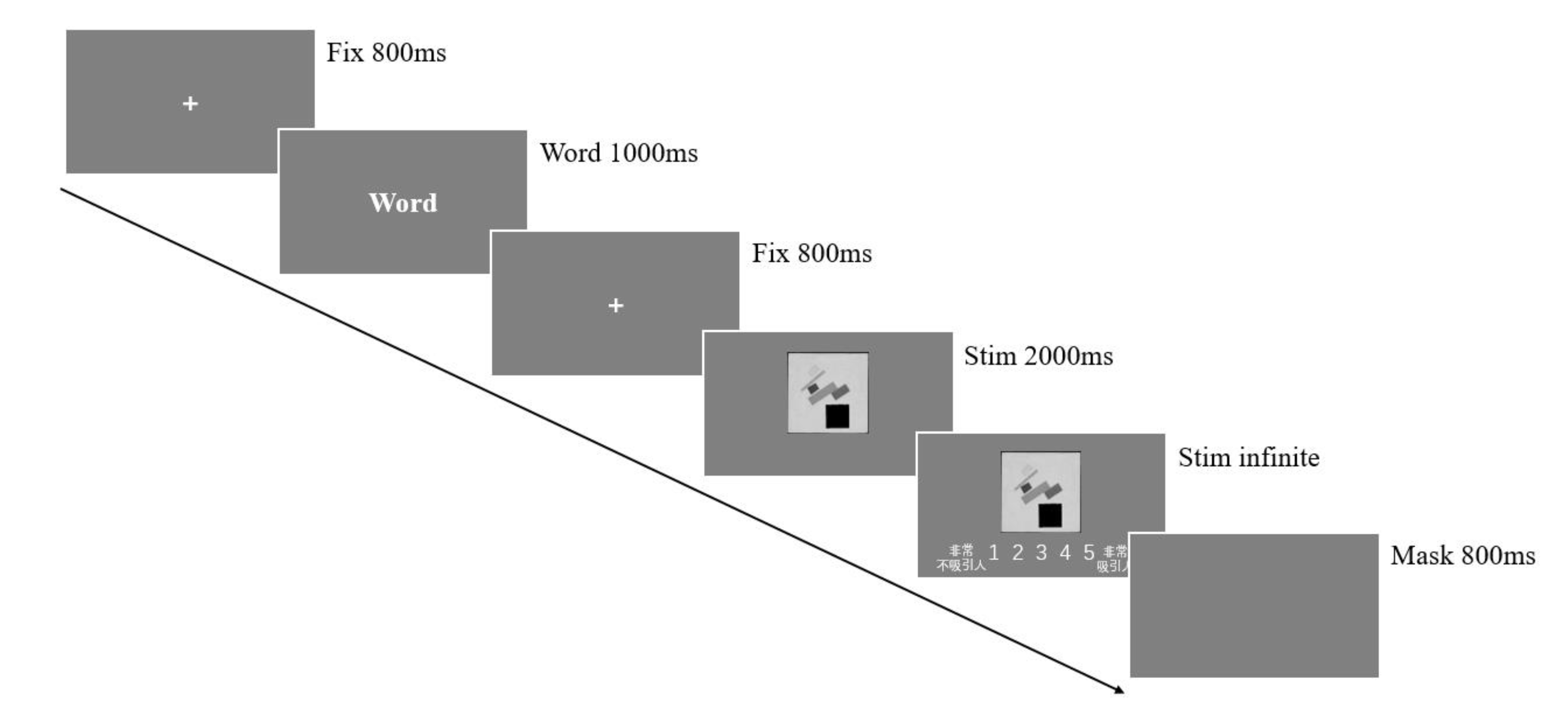

2.5. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Data

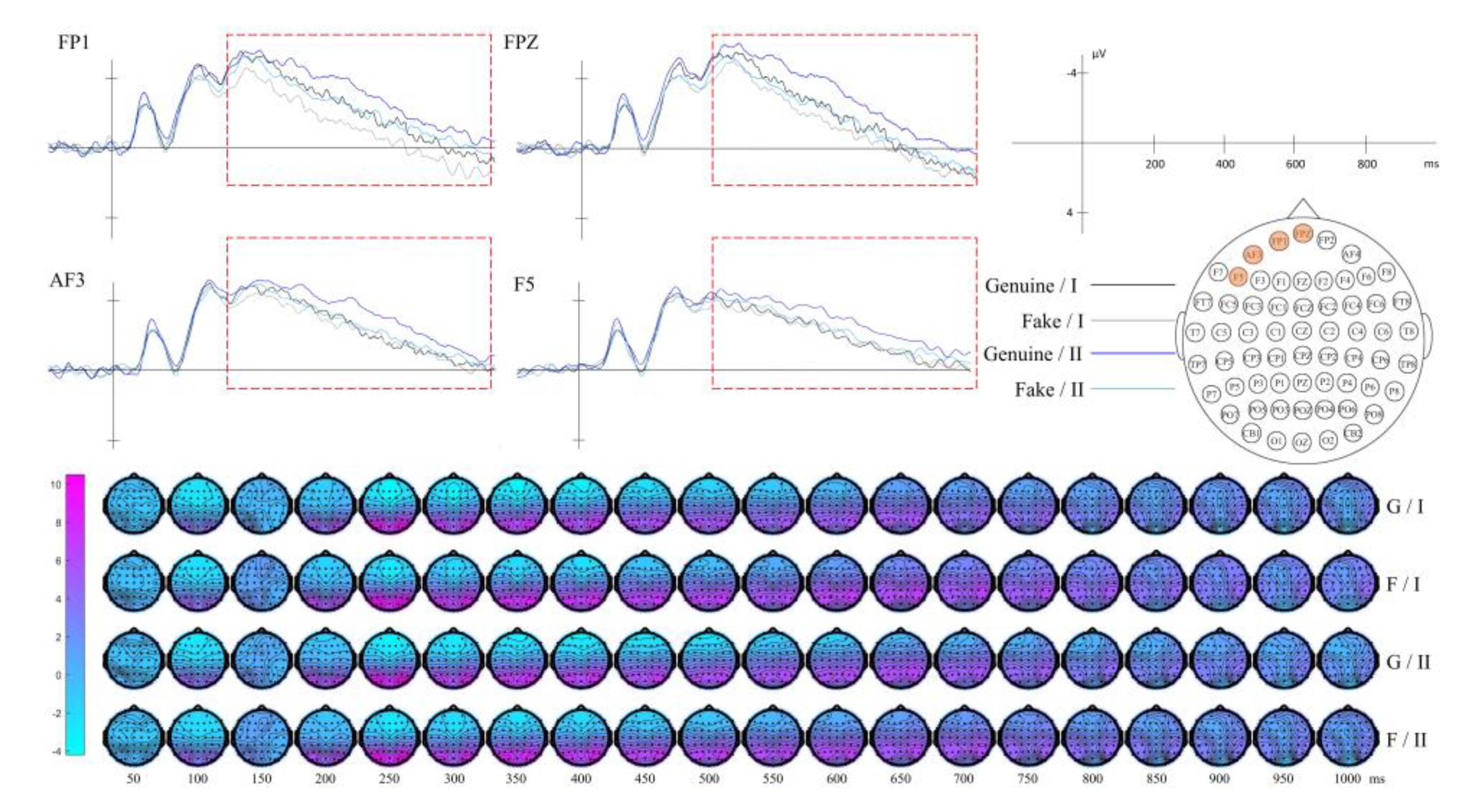

3.2. EEG Data

3.2.1. Result of Context

3.2.2. Result of Composition

3.2.3. Result of Tone

3.2.4. Result of Gabor-Mean

3.2.5. Result of Gabor-Variance

3.2.6. Result of Gabor - Energy

3.2.7. Result of Horizontal GLCM (θ=0°)

3.2.8. Result of Diagonal GLCM (θ=135°)

3.2.9. Result of LBP

4. Machine Learning Model

4.1. Dataset Construction

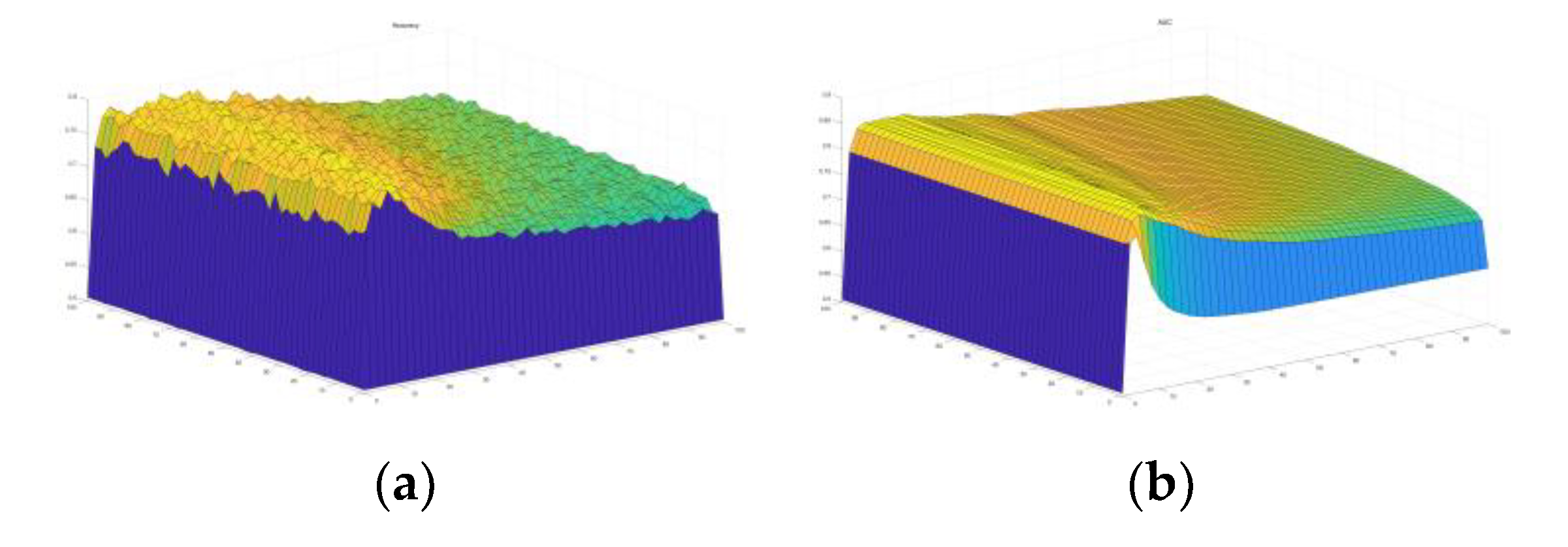

4.2. Parameter Determination

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Features | Class | Parameter | Mean | SD |

| Composition (Blank Space) |

I | Mean | 0.769 | 0.066 |

| II | Mean | 0.573 | 0.059 | |

| Tone (Gray Histogram) |

I | Mean | 108.774 | 31.488 |

| Variance | 5060.803 | 2820.122 | ||

| Skewness | 0.613 | 1.245 | ||

| Kurtosis | 0.774 | 5.617 | ||

| Energy | 4909.412 | 3298.131 | ||

| II | Mean | 179.912 | 25.290 | |

| Variance | 3306.247 | 1735.233 | ||

| Skewness | -1.676 | 1.167 | ||

| Kurtosis | 3.239 | 7.356 | ||

| Energy | 10016.353 | 13510.457 | ||

| Horizontal GLCM (θ=0°) | I | Contrast | 60369.94 | 10198.14 |

| Energy | 72.746 | 7.304 | ||

| Entropy | 783.655 | 59.472 | ||

| II | Contrast | 3131.599 | 272.695 | |

| Energy | 6.365 | 0.431 | ||

| Entropy | 95.516 | 5.242 | ||

| Diagonal GLCM (θ=135°) | I | Contrast | 115494.1 | 15748.78 |

| Energy | 88.365 | 8.009 | ||

| Entropy | 960.066 | 69.589 | ||

| II | Contrast | 7635.667 | 744.169 | |

| Energy | 7.038 | 0.468 | ||

| Entropy | 136.389 | 9.833 | ||

| LBP | I | Mean | 141.761 | 0.702 |

| Variance | 8982.159 | 23.793 | ||

| Skewness | -0.203 | 0.010 | ||

| Kurtosis | -1.530 | 0.005 | ||

| Energy | 29133.405 | 200.916 | ||

| II | Mean | 170.961 | 1.740 | |

| Variance | 8333.661 | 85.958 | ||

| Skewness | -0.708 | 0.039 | ||

| Kurtosis | -0.895 | 0.095 | ||

| Energy | 16563.702 | 439.355 |

Appendix B

| Features | Gabor-Mean | Gabor-Variance | Gabor-Energy | ||||||||||||

| Class I | Class II | Class I | Class II | Class I | Class II | Class II | |||||||||

| λ | θ | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 3 | 0 | 60.846 | 1.669 | 80.74 | 0.877 | 48.917 | 1.16 | 63.373 | 1.441 | 188.951 | 2.346 | 225.676 | 1.584 | ||

| 3 | π/8 | 71.264 | 2.009 | 104.904 | 1.247 | 44.264 | 1.193 | 57.174 | 1.165 | 209.145 | 2.047 | 239.915 | 1.021 | ||

| 3 | π/4 | 63.754 | 1.818 | 93.328 | 1.096 | 42.98 | 1.36 | 53.967 | 1.324 | 203.857 | 2.338 | 236.162 | 1.275 | ||

| 3 | 3π/8 | 71.366 | 1.996 | 104.918 | 1.270 | 44.871 | 1.208 | 57.028 | 1.101 | 209.131 | 2.063 | 239.566 | 0.999 | ||

| 3 | π/2 | 60.207 | 1.643 | 79.887 | 0.926 | 47.051 | 1.207 | 61.67 | 1.397 | 189.794 | 2.349 | 226.706 | 1.584 | ||

| 3 | 5π/8 | 71.118 | 1.984 | 104.798 | 1.266 | 44.118 | 1.227 | 56.482 | 1.106 | 209.672 | 2.102 | 240.196 | 0.987 | ||

| 3 | 3π/4 | 63.725 | 1.801 | 93.186 | 1.101 | 42.672 | 1.359 | 53.745 | 1.305 | 204.042 | 2.36 | 236.513 | 1.256 | ||

| 3 | 7π/8 | 71.324 | 1.979 | 104.947 | 1.26 | 44.414 | 1.2 | 57.431 | 1.094 | 209.228 | 2.049 | 239.901 | 0.997 | ||

| 6 | 0 | 7.041 | 0.527 | 2.328 | 0.199 | 19.378 | 0.975 | 36.913 | 1.481 | 8.703 | 0.602 | 2.509 | 0.203 | ||

| 6 | π/8 | 159.754 | 3.338 | 221.452 | 1.543 | 65.213 | 1.419 | 89.161 | 0.945 | 225.574 | 1.313 | 245.49 | 0.453 | ||

| 6 | π/4 | 175.236 | 3.273 | 230.479 | 1.223 | 57.481 | 1.541 | 83.868 | 1.03 | 233.441 | 1.208 | 248.162 | 0.41 | ||

| 6 | 3π/8 | 159.909 | 3.326 | 221.975 | 1.489 | 64.704 | 1.464 | 88.848 | 0.899 | 226.129 | 1.305 | 245.717 | 0.475 | ||

| 6 | π/2 | 6.448 | 0.483 | 1.678 | 0.143 | 16.578 | 0.886 | 35.335 | 1.331 | 7.877 | 0.552 | 1.903 | 0.16 | ||

| 6 | 5π/8 | 160.510 | 3.360 | 222.533 | 1.509 | 63.498 | 1.452 | 88.276 | 0.91 | 226.904 | 1.34 | 246.584 | 0.433 | ||

| 6 | 3π/4 | 175.775 | 3.306 | 230.954 | 1.230 | 56.498 | 1.482 | 83.439 | 1.048 | 233.823 | 1.22 | 248.884 | 0.353 | ||

| 6 | 7π/8 | 160.137 | 3.360 | 221.575 | 1.531 | 65.202 | 1.39 | 88.947 | 0.926 | 225.717 | 1.334 | 245.558 | 0.441 | ||

| 9 | 0 | 227.109 | 1.804 | 247.031 | 0.458 | 38.131 | 1.147 | 66.127 | 1.566 | 238.703 | 0.926 | 249.563 | 0.3 | ||

| 9 | π/8 | 13.813 | 0.708 | 6.5 | 0.347 | 32.714 | 0.922 | 55.135 | 1.089 | 19.708 | 0.807 | 7.066 | 0.34 | ||

| 9 | π/4 | 219.355 | 2.305 | 246.05 | 0.581 | 37.098 | 1.383 | 67.793 | 1.365 | 241.259 | 0.902 | 250.753 | 0.304 | ||

| 9 | 3π/8 | 13.679 | 0.722 | 6.055 | 0.343 | 31.914 | 1.038 | 54.132 | 1.163 | 18.918 | 0.809 | 6.808 | 0.372 | ||

| 9 | π/2 | 228.327 | 1.752 | 248.33 | 0.396 | 34.332 | 1.171 | 64.452 | 1.473 | 240.072 | 0.858 | 250.656 | 0.265 | ||

| 9 | 5π/8 | 12.660 | 0.712 | 5.391 | 0.314 | 29.388 | 0.889 | 52.421 | 1.118 | 18.194 | 0.813 | 5.901 | 0.303 | ||

| 9 | 3π/4 | 220.105 | 2.3465 | 246.49± | 0.566 | 35.687 | 1.277 | 66.999 | 1.372 | 241.749 | 0.917 | 251.293 | 0.259 | ||

| 9 | 7π/8 | 13.887 | 0.739 | 6.581 | 0.342 | 33.252 | 0.921 | 55.093 | 1.127 | 19.683 | 0.858 | 7.124 | 0.326 | ||

| 12 | 0 | 10.766 | 0.633 | 4.053 | 0.236 | 27.941 | 0.925 | 48.489 | 1.302 | 12.15 | 0.673 | 4.069 | 0.229 | ||

| 12 | π/8 | 16.008 | 0.787 | 7.124 | 0.342 | 36.547 | 0.946 | 59.815 | 1.162 | 19.566 | 0.826 | 7.116 | 0.32 | ||

| 12 | π/4 | 241.567 | 1.385 | 250.487 | 0.346 | 26.42 | 1.118 | 48.929 | 1.526 | 246.509 | 0.611 | 251.899 | 0.236 | ||

| 12 | 3π/8 | 14.901 | 0.774 | 6.42 | 0.332 | 34.564 | 0.971 | 57.421 | 1.213 | 18.097 | 0.822 | 6.668 | 0.334 | ||

| 12 | π/2 | 9.820 | 0.589 | 3.202 | 0.200 | 24.567 | 0.931 | 46.261 | 1.208 | 10.97 | 0.62 | 3.291 | 0.211 | ||

| 12 | 5π/8 | 14.085 | 0.770 | 5.674 | 0.308 | 32.073 | 0.86 | 56.061 | 1.181 | 17.412 | 0.819 | 5.726 | 0.275 | ||

| 12 | 3π/4 | 242.164 | 1.386 | 250.926 | 0.325 | 24.369 | 0.967 | 47.861 | 1.561 | 246.948 | 0.615 | 252.455 | 0.189 | ||

| 12 | 7π/8 | 15.648 | 0.808 | 7.137 | 0.328 | 36.724 | 0.912 | 59.076 | 1.216 | 19.129 | 0.858 | 7.114 | 0.296 | ||

| 15 | 0 | 39.947 | 1.420 | 26.953 | 0.998 | 69.6 | 1.166 | 89.118 | 1.119 | 54.754 | 1.404 | 30.268 | 1.034 | ||

| 15 | π/8 | 226.967 | 1.642 | 244.075 | 0.502 | 45.802 | 1.016 | 74.387 | 1.257 | 232.332 | 1.016 | 246.376 | 0.373 | ||

| 15 | π/4 | 248.298 | 0.978 | 252.998 | 0.208 | 16.308 | 1.008 | 33.632 | 1.602 | 250.527 | 0.443 | 253.465 | 0.156 | ||

| 15 | 3π/8 | 228.557 | 1.579 | 245.44 | 0.487 | 42.801 | 1.111 | 71.819 | 1.3 | 234.201 | 0.951 | 247.353 | 0.38 | ||

| 15 | π/2 | 37.557 | 1.419 | 24.238 | 0.957 | 65.499 | 1.305 | 86.464 | 1.166 | 52.398 | 1.363 | 27.638 | 1.024 | ||

| 15 | 5π/8 | 229.281 | 1.585 | 245.979 | 0.474 | 41.009 | 1.037 | 71.066 | 1.304 | 234.8 | 0.958 | 248.074 | 0.333 | ||

| 15 | 3π/4 | 248.6452 | 0.968 | 253.244 | 0.192 | 14.363 | 0.868 | 32.833 | 1.622 | 250.759 | 0.437 | 253.803 | 0.131 | ||

| 15 | 7π/8 | 227.472 | 1.653 | 244.578 | 0.5 | 44.604 | 0.995 | 73.665 | 1.309 | 232.715 | 1.043 | 246.833 | 0.348 | ||

References

- Baumgarten, A.G. Aesthetica; impens. Ioannis Christiani Kleyb, 1763.

- Semir·zeki. Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain; Oxford University Press: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Leder, H.; Belke, B.; Oeberst, A.; Augustin, D. A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. The British journal of psychology 2004, 95, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leder, H.; Nadal, M. Ten years of a model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments: The aesthetic episode - Developments and challenges in empirical aesthetics. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, M.W.; Reynolds, G.D.; Mosteller, S.M.; Dixon, K.C. The effects of stimulus symmetry on hierarchical processing in infancy. Dev. Psychobiol. 2017, 59, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, T.; Höfel, L. Aesthetics Electrified: An Analysis of Descriptive Symmetry and Evaluative Aesthetic Judgment Processes Using Event-Related Brain Potentials. Empir. Stud. Arts 2001, 19, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, H.; Tinio, P.P.L.; Brieber, D.; Kröner, T.; Jacobsen, T.; Rosenberg, R. Symmetry Is Not a Universal Law of Beauty. Empir. Stud. Arts 2019, 37, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodine, C.F.; Locher, P.J.; Krupinski, E.A. The Role of Formal Art Training on Perception and Aesthetic Judgment of Art Compositions. Leonardo 1993, 26, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, S.; Chén, O.Y.; Romaya, J.P. The Biological Basis of Mathematical Beauty. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, U.; Skov, M.; Hulme, O.; Christensen, M.S.; Zeki, S. Modulation of aesthetic value by semantic context: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 2009, 44, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüner, S.; Specker, E.; Leder, H. Effects of Context and Genuineness in the Experience of Art. Empir. Stud. Arts 2019, 37, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkhoff, G.D. Aesthetic measure; Harvard University Press, 1933.

- Liu, Y. Engineering aesthetics and aesthetic ergonomics: Theoretical foundations and a dual-process research methodology. Ergonomics 2003, 13/14, 1273–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M. Beauty in artistic expressions through the eyes of networks and physics. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20190686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenig, F. Defining Computational Aesthetics, Computational Aesthetics in Graphics, Visualization and Imaging, 2005, 2005.

- Haralick, R.M. Statistical and Structural Approaches to Texture. Proc. IEEE 1979, 67, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falomir, Z.; Museros, L.; Sanz, I.; Gonzalez-Abril, L. Categorizing paintings in art styles based on qualitative color descriptors, quantitative global features and machine learning (QArt-Learn). Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 97, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, C.; Pirogova, E.; Lech, M. Two-stage deep learning approach to the classification of fine-art paintings. IEEE Access 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Huang, X.; Xiao, Z. Fine-art painting classification via two-channel dual path networks. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2020, 11, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, L.; Cornia, M.; Grana, C.; Cucchiara, R. Aligning Text and Document Illustrations: Towards Visually Explainable Digital Humanities, 2018; IEEE, 2018.

- Tan, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lewis, M.; Jarrold, W. CNN Models for Classifying Emotions Evoked by Paintings; Technical Report, SVL Lab, Stanford University, USA, 2018.

- Yanulevskaya, V.; Uijlings, J.; Bruni, E.; Sartori, A.; Zamboni, E.; Bacci, F.; Melcher, D.; Sebe, N. In the eye of the beholder: employing statistical analysis and eye tracking for analyzing abstract paintings, 2012; ACM, 2012.

- Markovic, S. Perceptual, Semantic and Affective Dimensions of Experience of Abstract and Representational Paintings. Psihologija 2011, 44, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon, D. The forest revisited: More on global precedence. Psychological research 1981, 43, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Building the gist of a scene: the role of global image features in recognition. Prog. Brain Res. 2006, 155, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Navon, D. Forest before trees: The precedence of global features in visual perception. Cogn. Psychol. 1977, 9, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, A.C.; Braun, D.I.; Gegenfurtner, K.R. Eye movements and perception: A selective review. J. Vision 2011, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, B.C.; Rouder, J.N.; Wisniewski, E.J. A structural account of global and local processing. Cogn. Psychol. 1999, 38, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharvashidze, N.; Schutz, A.C. Task-Dependent Eye-Movement Patterns in Viewing Art. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Wiliams, L.; Chamberlain, R. Global Saccadic Eye Movements Characterise Artists’ Visual Attention While Drawing. Empir. Stud. Arts 2022, 40, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, N.; Kubo, T.; Nishida, S.; Shibata, T.; Ikeda, K. Art expertise reduces influence of visual salience on fixation in viewing abstract-paintings. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soxibov, R. COMPOSITION AND ITS APPLICATION IN PAINTING. Sci. Innov. 2023, 2, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lelievre, P.; Neri, P. A deep-learning framework for human perception of abstract art composition. J Vis 2021, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Shen, J.; Yue, M.; Ma, Y.; Wu, S. A Computational Study of Empty Space Ratios in Chinese Landscape Painting, 618–2011. Leonardo (Oxford) 2022, 55, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, X.S. Evaluation and Analysis of White Space in Wu Guanzhong’s Chinese Paintings. Leonardo 2019, 52, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmeyer, C.L. The Study of Drawing—Tone Values and Harmony—The Knowledge of Technique. Fine arts journal (Chicago, Ill. 1899) 1912, 27, 679–709. [Google Scholar]

- Close, C.; Hinks, M.; Mill, H.R.; Cornish, V. Harmonies of Tone and Colour in Scenery Determined by Light and Atmosphere: Discussion. The Geographical journal 1926, 67, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Qin, X.; Liu, T. Exploring the Influence of the Illumination and Painting Tone of Art Galleries on Visual Comfort. Photonics 2022, 9, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 1973, SMC-3, 610-621.

- Ojala, T.; Pietikainen, M.; Maenpaa, T. Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammouda, K.; Jernigan, E. Texture segmentation using gabor filters. Cent. Intell. Mach 2000, 2, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yu, J.; Huang, M.L. Measuring and Evaluating the Visual Complexity Of Chinese Ink Paintings. Comput. J. 2022, 65, 1964–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, R.A.; Bentley, J.L. Quad trees a data structure for retrieval on composite keys. Acta Inform. 1974, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, H. Über das elektroenkephalogramm des menschen. Archiv für psychiatrie und nervenkrankheiten 1929, 87, 527–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, W.G.; Cooper, R.; Aldridge, V.J.; Mccallum, W.C.; Winter, A.L. Contingent Negative Variation: An Electric Sign of Sensori-Motor Association and Expectancy in the Human Brain. Nature (London) 1964, 203, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boser, B.; Guyon, I.; Vapnik, V. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers, 1992; ACM, 1992.

- Wong, K.K. Cybernetical intelligence: Engineering cybernetics with machine intelligence; John Wiley & Sons, 2023.

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Lin, C. LIBSVM: a library for support vector machines. ACM transactions on intelligent systems and technology (TIST) 2011, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawe-Taylor, J.; Cristianini, N. Kernel methods for pattern analysis; Cambridge university press, 2004.

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern recognition and machine learning; Springer, 2006.

- Noguchi, Y.; Murota, M. Temporal dynamics of neural activity in an integration of visual and contextual information in an esthetic preference task. Neuropsychologia 2013, 51, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüner, S.; Specker, E.; Leder, H. Effects of Context and Genuineness in the Experience of Art. Empir. Stud. Arts 2019, 37, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcu, E.B. The Rationale for a Redefinition of Visual Art Based on Neuroaesthetic Principles. Leonardo 2018, 51, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbriscia-Fioretti, B.; Berchio, C.; Freedberg, D.; Gallese, V.; Umiltà, M.A.; Di Russo, F. ERP modulation during observation of abstract paintings by Franz Kline. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Doherty, J.; Critchley, H.; Deichmann, R.; Dolan, R.J. Dissociating valence of outcome from behavioral control in human orbital and ventral prefrontal cortices. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 7931–7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W.; Tremblay, L. Relative reward preference in primate orbitofrontal cortex. Nature (London) 1999, 398, 704–708. [Google Scholar]

- Thai, C.H. Electrophysiological Measures of Aesthetic Processing, Swinburne University of Technology Melbourne, 2019.

- Munar, E.; Nadal, M.; Rosselló, J.; Flexas, A.; Moratti, S.; Maestú, F.; Marty, G.; Cela-Conde, C.J.; Martinez, L.M. Lateral orbitofrontal cortex involvement in initial negative aesthetic impression formation. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medathati, N.V.K.; Neumann, H.; Masson, G.S.; Kornprobst, P. Bio-inspired computer vision: Towards a synergistic approach of artificial and biological vision. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2016, 150, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.D.; Goodale, M.A. Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodale, M.A.; Milner, A.D. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in neurosciences (Regular ed.) 1992, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasdel, G.G. Differential imaging of ocular dominance and orientation selectivity in monkey striate cortex. The Journal of neuroscience 1992, 12, 3115–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubel, D.H.; Wiesel, T.N. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat's visual cortex. The Journal of physiology 1962, 160, 106–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhalter, A.; Felleman, D.J.; Newsome, W.T.; Van Essen, D.C. Anatomical and physiological asymmetries related to visual areas V3 and VP in macaque extrastriate cortex. Vision research (Oxford) 1986, 26, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felleman, D.J.; Van Essen, D.C. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 1991, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, A.W.; Ts'O, D.Y. Visual topography in primate V2: multiple representation across functional stripes. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 3689–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, J.; Van Essen, D.C. Selectivity for Complex Shapes in Primate Visual Area V2. The Journal of neuroscience 2000, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desimone, R.; Schein, S.J. Visual properties of neurons in area V4 of the macaque: sensitivity to stimulus form. J. Neurophysiol. 1987, 57, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, S. Colour coding in the cerebral cortex: the reaction of cells in monkey visual cortex to wavelengths and colours. Neuroscience 1983, 9, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome, W.T.; Pare, E.B. A selective impairment of motion perception following lesions of the middle temporal visual area (MT). J. Neurosci. 1988, 8, 2201–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, S.J.; Hillyard, S.A. Spatial filtering during visual search: evidence from human electrophysiology. J. Exp. Psychol.-Hum. Percept. Perform. 1994, 20, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, V.P.; Hillyard, S.A. Spatial selective attention affects early extrastriate but not striate components of the visual evoked potential. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1996, 8, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.; Ramanathan, D.S.; Foxe, J.J.; Javitt, D.C.; Hillyard, S.A. The role of spatial attention in the selection of real and illusory objects. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 7963–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. Evaluation of Aesthetic Response to Clothing Color Combination: A Behavioral and Electrophysiological Study. Journal of Fiber Bioengineering and Informatics 2018, 6, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Lau, B.T.; White, D.; Barron, D.; Zhang, W.; Yue, Y.; Ogiela, M. Artificial Aesthetics: Bridging Neuroaesthetics and Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhang, J. Review of computational neuroaesthetics: bridging the gap between neuroaesthetics and computer science. Brain Inform. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botros, C.; Mansour, Y.; Eleraky, A. Architecture Aesthetics Evaluation Methodologies of Humans and Artificial Intelligence. MSA Engineering Journal 2023, 2, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Class | N | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | I | 123 | Class I has a larger blank area compared to Class II. |

| II | 126 | ||

| Tone | I | 105 | The average brightness of Class I is lower than that of Class II, and the gray-level distribution is more discrete. |

| II | 144 | ||

| Gabor-Mean | I | 117 | In the following combinations - (6, 0), (6, π/2), (9, π/8), (9, 3π/8), (9, 5π/8), (9,7π/8), (12,0), (12, π/8) , (12, 3π/8), (12, π/2), (12, 5π/8), (12, 7π/8), (15,0) , (15, π/2) , the grayscale mean of the filtered images in Class I is higher than that of Class II. This indicates that Class I has a higher overall brightness in these combinations. Conversely, Class II exhibits more high-brightness features in other combinations. |

| II | 132 | ||

| Gabor-Variance | I | 130 | In all the combinations, Class II has more high-frequency components and greater texture changes after Gabor filter processing, which suggests that it contains more diverse and complex textures. |

| II | 119 | ||

| Gabor-Energy | I | 122 | In the following combinations - (6, 0), (6, π/2), (9, π/8), (9, 3π/8), (9, 5π/8), (9,7π/8), (12,0), (12, π/8) , (12, 3π/8), (12, π/2), (12, 5π/8), (12, 7π/8), (15,0) , (15, π/2) - the energy gray level of Class I after Gabor filter processing is greater. The features in Class I are more pronounced and intense, likely containing more edges, lines, or texture features in these combinations. Conversely, Class II contains more prominent edges or complex textures in other combinations. |

| II | 127 | ||

| Horizontal GLCM (θ=0°) | I | 123 | In the horizontal direction, compared to Class II, the texture features of Class I are more obvious, with high-contrast edges and lines, higher regularity, and more texture patterns. |

| II | 126 | ||

| Diagonal GLCM (θ=135°) | I | 118 | In the diagonal direction, compared to Class II, the texture features of Class I are more obvious, with high-contrast edges and lines, higher regularity, and more texture patterns. |

| II | 131 | ||

| LBP | I | 113 | Compared to Class II, Class I has weaker texture contrast, but richer details, uniform texture distribution, and contains more small and intense details. |

| II | 136 |

| Input Layer | Output Layer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context and Features | Average amplitude of ERP / μV | |||

| Channel | Time Window / ms | |||

| Context | Genuine/Fake | FP1, FPZ, FP2 | 200-1000 | Aesthetic Evaluation |

| Composition | Blank Space | PZ, POZ | 50-120 | |

| Tone | Gray Histogram | OZ | 200-300 | |

| Global Texture | Gabor-Mean | P7, PO3, PO5, PO7 | 70-130 | |

| Gabor-Variance | PZ, POZ | 70-130 | ||

| Gabor-Energy | P2, P4, PZ, PO4, PO6, POZ | 70-130 | ||

| Local Texture | Horizontal GLCM | OZ | 500-1000 | |

| Diagonal GLCM | PO5, PO7 | 70-140 | ||

| OZ | 300-1000 | |||

| LBP | AF3, P5, FP1, FPZ | 300-1000 | ||

| Metrics | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Best C | 28.5786 | |

| Best γ | 14.2943 | |

| Train ACC | 0.79801 | |

| Test ACC | 0.76866 | |

| AUC | 0.74155 | |

| Precision | 0.78241 | 0.75269 |

| Recall | 0.78605 | 0.74866 |

| F1 | 0.78422 | 0.75067 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).