Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

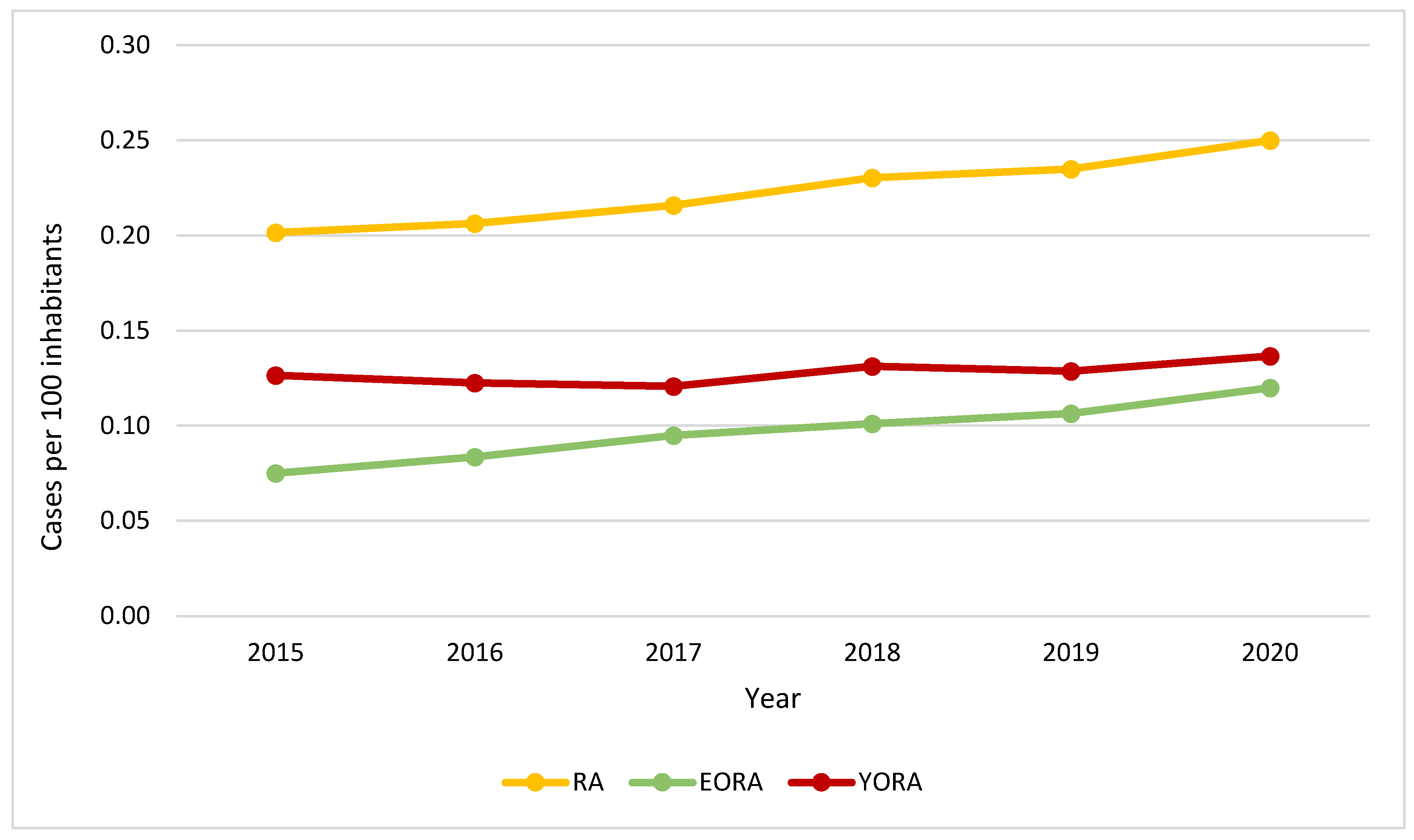

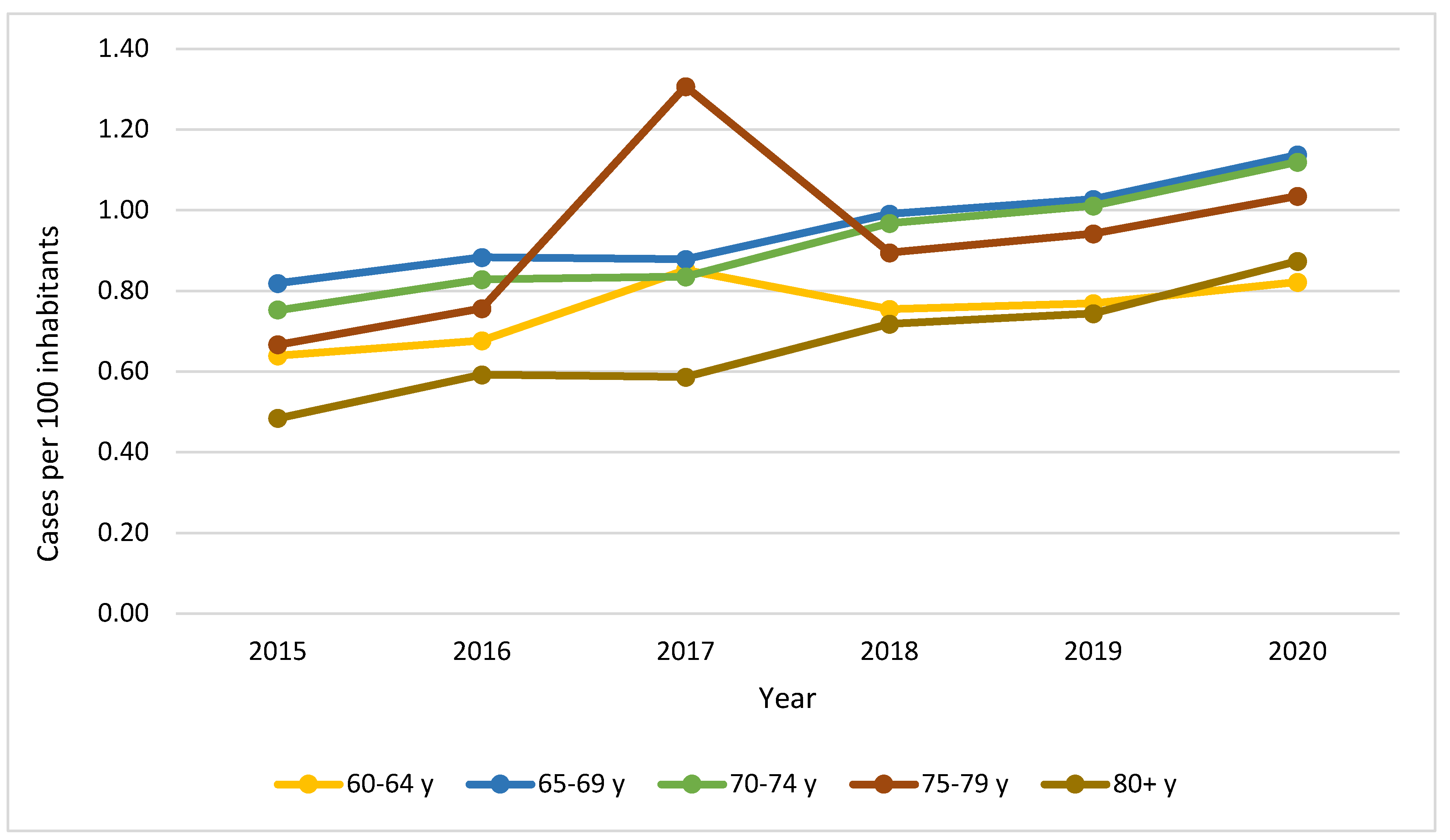

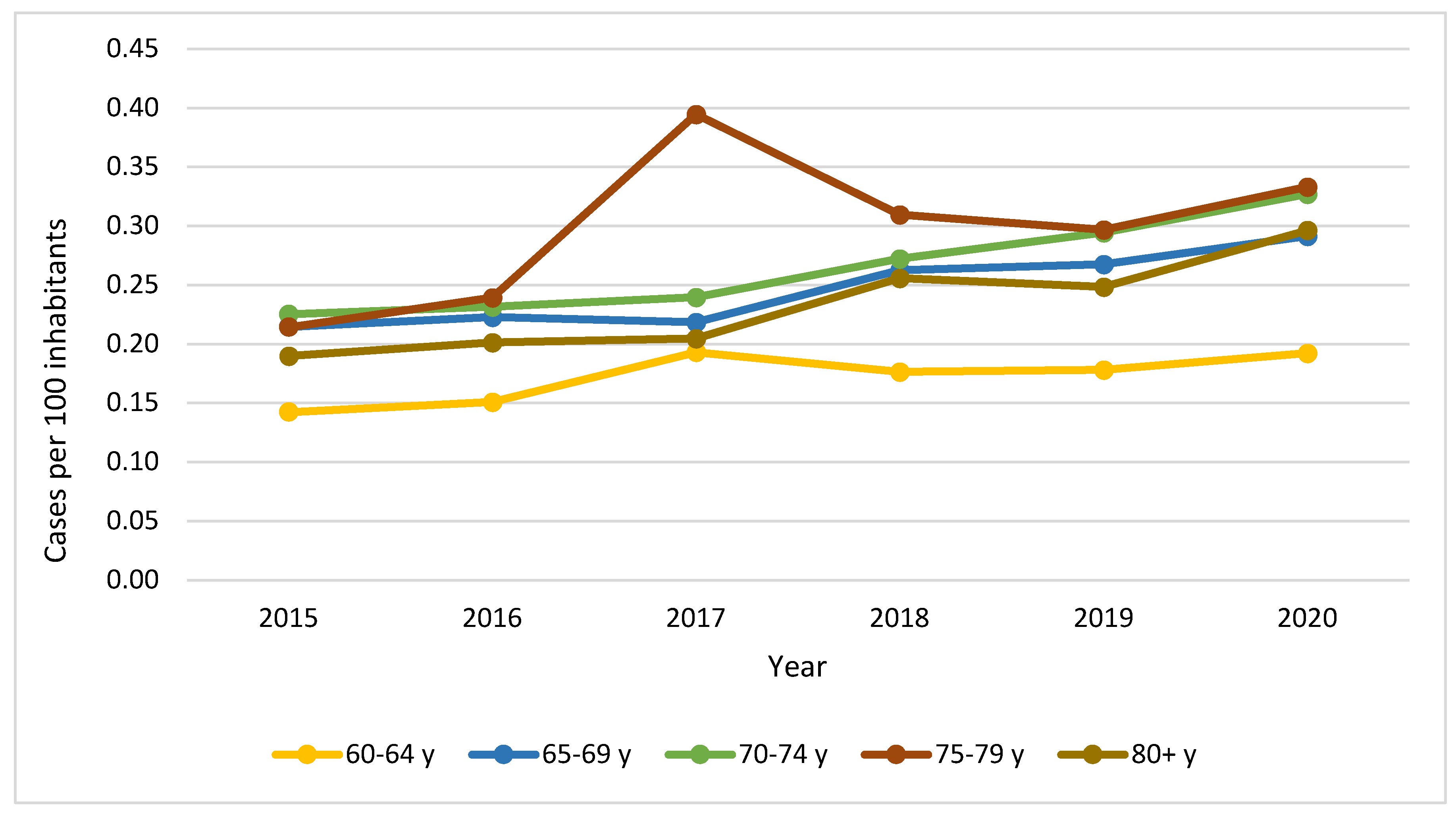

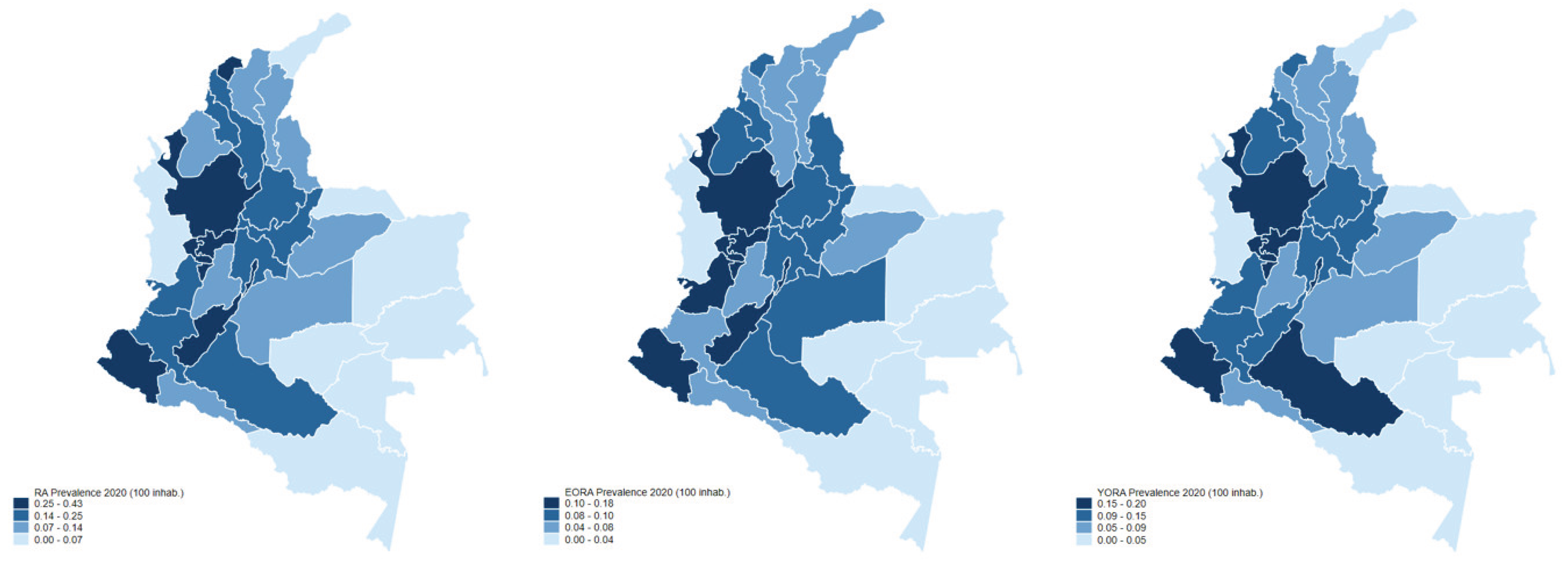

Objective: This study aims to investigate the prevalence of elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) in Colombia, analyzing demographics, clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and therapeutics characteristics of EORA patients. Furthermore, it compares these with findings observed in patients affected by young-onset rheumatoid arthritis (YORA). Methods: A secondary analysis was conducted using records of all adults diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) between 2015 and 2020 reported from 2015-2020 to the High-Cost Account, a division of the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection. Comparative analyses were performed on incident cases to highlight differences between EORA and YORA patients. Results: 195.292 cases were included for prevalence analysis, with 24.933 incident cases for comparative purposes. In 2020, the prevalence of EORA in Colombia increased to 0.12%. Compared to YORA, EORA was more frequently observed in males (p <0.001), with a significantly longer time to diagnosis (p <0,001). There were no differences in disease activity assessed by DAS28 (p = 0.438). At diagnosis, EORA patients were more likely to test negative for anti-CCP (p <0.001), rheumatoid factor (p <0.001), and C-reactive protein (p = 0,005). Moreover, the use of antirheumatic drugs was less frequent among EORA patients. Conclusion: Compared to YORA, EORA patients experience delayed time to diagnosis, less frequent presence of positive auto-antibodies, acute-phase reactants, and reduced use of biological therapy. These findings suggest that EORA may have a less aggressive disease course than YORA.

Keywords:

Importance and Innovations

Introduction

Methods

Study Design and Selection of the Sample

Variables of Interest

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Serhal L, Lwin MN, Holroyd C, Edwards CJ. Rheumatoid arthritis in the elderly: Characteristics and treatment considerations. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 Jun;19(6).

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising? Results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955-2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1576–82.

- Rasch EK, Hirsch R, Paulose-Ram R, Hochberg MC. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in persons 60 years of age and older in the United States: Effect of different methods of case classification. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Apr;48(4).

- Targońska-Stępniak B, Grzechnik K, Kolarz K, Gągoł D, Majdan M. Systemic Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Elderly-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis (EORA) and Young-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis (YORA)—An Observational Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(6):1204.

- Soubrier M, Mathieu S, Payet S, Dubost JJ, Ristori JM. Elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Vol. 77, Joint Bone Spine. 2010.

- Ruban TN, Jacob B, Pope JE, Keystone EC, Bombardier C, Kuriya B. The influence of age at disease onset on disease activity and disability: results from the Ontario Best Practices Research Initiative. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(3):759–63.

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1580–8.

- Olivieri I, Palazzi C, Peruz G. Management issues with elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis: An update. Vol. 22, Drugs and Aging. 2005.

- Soubrier M, Mathieu S, Payet S, Dubost JJ, Ristori JM. Elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Jt Bone Spine [Internet]. 2010;77(4):290–6. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Ndongo, S. Effect of Age on Rheumatoid Arthritis in a Black Senegalese Population. Rheumatol Curr Res. 2011;01(02):2–4.

- Carbonell J, Cobo T, Balsa A, Descalzo MÁ, Carmona L. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: Results from a nationwide primary care registry. Rheumatology. 2008;47(7):1088–92.

- Gutiérrez W, Samudio ML, Fernández-Ávila DG, Díaz MC, Gutiérrez JM. Artritis reumatoide en el anciano. Revisión narrativa. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2013;20(2):91–101.

- Mueller RB, Kaegi T, Finckh A, Haile SR, Schulze-koops H, Von kempis J. Is radiographic progression of late-onset rheumatoid arthritis different from young-onset rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the swiss prospective observational cohort. Rheumatol (United Kingdom). 2014;53(4):671–7.

- Spinel-Bejarano N, Quintana G, Heredia R, Yunis JJ, Caminos JE, Garcés MF, et al. Comparative study of elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis and young-onset rheumatoid arthritis in a Colombian population: Clinical, laboratory and HLA-DRB1 findings. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(1):40–6.

- Won S, Cho S-K, Kim D, Han M, Lee J, Jang EJ, et al. Update on the prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Korea and an analysis of medical care and drug utilization. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;781632. 2018 Apr 4;38(4).

- Kuo CF, Luo SF, See LC, Chou IJ, Chang HC, Yu KH. Rheumatoid arthritis prevalence, incidence, and mortality rates: A nationwide population study in Taiwan. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(2):355–60.

- Jaouad N, Amine B, Elbinoune I, Rostom S, Bahiri R. Comparison of elderly and young onset rheumatoid. 2022;4(3):1–7.

- Turkcapar N, Demir O, Atli T, Kopuk M, Turgay M, Kinikli G, et al. Late onset rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical and laboratory comparisons with younger onset patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;42(2):225–31.

- Ke Y, Dai X, Xu D, Liang J, Yu Y, Cao H, et al. Features and Outcomes of Elderly Rheumatoid Arthritis: Does the Age of Onset Matter? A Comparative Study From a Single Center in China. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(1):243–54.

- Maassen JM, Bergstra SA, Chopra A, Govind N, Murphy EA, Vega-Morales D, et al. Phenotype and treatment of elderly onset compared with younger onset rheumatoid arthritis patients in international daily practice. Rheumatol (United Kingdom). 2021;60(10):4801–10.

- Murata K, Ito H, Hashimoto M, Nishitani K, Murakami K, Tanaka M, et al. Elderly onset of early rheumatoid arthritis is a risk factor for bone erosions, refractory to treatment: KURAMA cohort. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(6):1084–93.

- Van der Heijde, D. M. , van Riel, P. L. van L. Older versus younger onset rheumatoid arthritis: results at onset and after 2 years of a prospective followup study of early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(9), 1285–1289.

- Inoue K, Shichikawa K, Nishioka J, Hirota S. Older age onset rheumatoid arthritis with or without osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987;46(12):908–11.

- Krams T, Ruyssen-Witrand A, Nigon D, Degboe Y, Tobon G, Fautrel B, et al. Effect of age at rheumatoid arthritis onset on clinical, radiographic, and functional outcomes: The ESPOIR cohort. Jt Bone Spine [Internet]. 2016;83(5):511–5. Available from. [CrossRef]

- I. Yoshii TC. Clinical characteristics of elderly onset rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) compared to young onset rheumatoid arthritis (YORA) in young and old. 2016.

- Rajalingham S, Shaharir SS, Mahadzir H. Comparative analyses of serological biomarkers and disease characteristics between elderly onset rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) and younger onset rheumatoid arthritis (YORA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2021.

- Terán MA, Pijoan C, Quiñones J. Elderly-onset rheumatoid arhtritis (EORA): Differences according to clinical debut and serological positivity. Ann Rheum Dis.

- Horiuchi AC, Pereira LHC, Kahlow BS, Silva MB, Skare TL. Rheumatoid arthritis in elderly and young patients. Rev Bras Reumatol (English Ed [Internet]. 2017;57(5):491–4. Available from. [CrossRef]

- I. Coman, I. I. Coman, I. Elisei VB. Elderly onset rhaumatoid arthritis (EORA): What to expect in real life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tutuncu Z, Reed G, Kremer J, Kavanaugh A. Do patients with older-onset rheumatoid arthritis receive less aggressive treatment? Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(9).

- Zhang M, Feng M, Lai B. The comprehensive geriatric assessment of an older adult with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Autoimmun. 2022;2(2):102–4.

- El-Labban AS, Abo Omar HAS, El-Shereif RR, Ali F, El-Mansoury TM. Pattern of young and old onset rheumatoid arthritis (YORA and EORA) among a group of Egyptian patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;3.

- Bajocchi G, La Corte R, Locaputo A, Govoni M, Trotta F. Elderly onset rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical aspects. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(SUPPL. 20).

- Pavlov-Dolijanovic S, Bogojevic M, Nozica-Radulovic T, Radunovic G, Mujovic N. Elderly-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis: Characteristics and Treatment Options. Med. 2023;59(10):1–21.

- Bes, C. An autumn tale: Geriatric rheumatoid arthritis. Vol. 10, Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 2018.

- Davison, S. Rheumatic disease in the elderly. Mt Sinai J Med. 1980;47(2):175–80.

- Villa-Blanco JI, Calvo-Alén J. Elderly onset rheumatoid arthritis: Differential diagnosis and choice of first-line and subsequent therapy. Drugs and Aging. 2009;26(9):739–50.

- Ohta R, Sano C. Differentiating between Seronegative Elderly-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica: A Qualitative Synthesis of Narrative Reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3).

- Castro-Rueda H, Kavanaugh A. Biologic therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: The latest evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(3):314–9.

| Characteristic1 | YORA Age ≤ 60 (n=16.899) |

EORA Age > 60 (n=8.034) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age2 | 49 (40-55) | 69 (64-75) | |

| Age at symptom onset2 | 45 (36-52) | 65 (61-71) | |

| Time to diagnosis (years)2 | 2 (1-5) | 3 (1-9) | <0.001 |

| Time to diagnosis (months)2 | 13 (6-36) | 18 (6-58) | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis2 | 48 (39-54) | 68 (64-74) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 14,165 (83.82) | 6,100 (75.93) | <0.001 |

| Male | 2,734 (16.18) | 1,934 (24.07) | |

| Region of residency | |||

| Central | 4,862 (28.77) | 2,346 (29.20) | |

| Bogotá D.C. | 4,401 (26.04) | 2,189 (27.25) | 0.012 |

| Pacific | 2,807 (16.61) | 1,288 (16.03) | |

| Oriental | 2,352 (13.92) | 1,107 (13.78) | |

| Caribbean | 2,262 (13.39) | 1,037 (12.91) | |

| Amazonía-Orinoquía | 215 (1.27) | 67 (0.83) | |

| Regime of coverage | |||

| Contributive | 10,982 (64.99) | 4,946 (61.55) | <0.001 |

| Subsidized | 5,180 (30.65) | 2,633 (32.77) | |

| Other | 737 (4.36) | 457 (5.68) | |

| Anti-CCP | |||

| Positive | 4,811 (28.47) | 1,927 (23.99) | |

| Negative | 3,112 (18.42) | 1,630 (20.29) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 8,976 (53.12) | 4,477 (55.73) | |

| RF at diagnosis | |||

| Positive | 9,007 (53.30) | 3,992 (49.69) | |

| Negative | 4,350 (25.74) | 2,140 (26.64) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 3,542 (20.96) | 1,902 (23.67) | |

| CRP at diagnosis | |||

| Reactive | 6,280 (37.16) | 2,845 (35.41) | |

| No reactive | 70 (0.41) | 48 (0.60) | 0.005 |

| Unknown | 10,549 (62.42) | 5,141 (63.99) | |

| ESR (mm/h)2 | 20 (10-35) | 24 (13-41) | <0.001 |

| Disease activity (DAS28) | |||

| Remission (0.0-<2.6) | 2,648 (15.67) | 1,313 (16.34) | 0.438 |

| Low activity (≥2.6-<3.2) | 1,137 (6.73) | 573 (7.13) | |

| Moderate activity (≥3.2-≤5.1) | 3,557 (21.05) | 1,675 (20.85) | |

| High activity (>5.1-10) | 1,734 (10.26) | 820 (10.21) | |

| Unknown | 7,823 (46.29) | 3,653 (45.47) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| High blood pressure | 2,400 (14.20) | 2,929 (36.46) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,080 (6.39) | 1,037 (12.91) | <0.001 |

| Sjogren’s syndrome | 865 (5.12) | 406 (5.05) | 0.059 |

| Osteoporosis | 775 (4.59) | 982 (12.22) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 655 (3.88) | 424 (5.28) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 630 (3.73) | 355 (4.42) | 0.021 |

|

Anti-CCP: cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. RF: rheumatoid factor. ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate. DAS28: Disease Activity Score-28 *Information on prevalence (per 100 people) as estimated by the administrative registry of persons with RA under coverage by the Colombian public health system | |||

| 1Descriptive results presented only for new cases, in absolute values (percentages) | |||

| 2Information presented as median (interquartile range) | |||

| Use of drugs1 | YORA Age ≤ 60 (n=16,899) |

EORA Age > 60 (n=8,034) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics and glucocorticoids | |||

| Non opioids (acetaminophen-dipyrone) | 4.883 (28,90) | 2.671 (33,25) | <0,001 |

| Opioids (codeine-tramadol) | 1.062 (6,28) | 638 (7,94) | <0,001 |

| NSAID | 3.768 (22,30) | 1.372 (17,08) | <0,001 |

| Glucocorticoids | 9.446 (55,90) | 4.318 (53,75) | 0,005 |

| Conventional (synthetic) DMARD | |||

| Methotrexate | 9.927 (58,74) | 4.366 (54,34) | <0,001 |

| Chloroquine | 4.494 (26,59) | 1.963 (24,43) | 0,001 |

| Leflunomide | 2.770 (16,39) | 1.382 (17,20) | 0,009 |

| Sulfasalazine | 1.329 (7,86) | 629 (7,83) | 0,482 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 368 (2,18) | 177 (2,20) | 0,317 |

| Azathioprine | 111 (0,66) | 52 (0,65) | 0,313 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 20 (0,12) | 13 (0,16) | 0,287 |

| Tofacitinib | 18 (0,11) | 10 (0,12) | 0,290 |

| Cyclosporine | 5 (0,03) | 6 (0,07) | 0,121 |

| D-Penicillamine | 3 (0,02) | 6 (0,07) | 0,016 |

| Biological DMARD | |||

| Rituximab | 127 (0,75) | 46 (0,57) | 0,120 |

| Etanercept | 118 (0,70) | 43 (0,54) | 0,035 |

| Adalimumab | 67 (0,40) | 19 (0,24) | 0,042 |

| Abatacept | 55 (0,33) | 22 (0,27) | 0,045 |

| Certolizumab | 51 (0,30) | 26 (0,32) | 0,180 |

| Tocilizumab | 33 (0,20) | 21 (0,26) | 0,244 |

| Golimumab | 19 (0,11) | 7 (0,09) | 0,359 |

| Infliximab | 16 (0,09) | 8 (0,10) | 0,312 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).