1. Introduction

Adult-onset Still's disease (AOSD) and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), which is now considered to be an earlier form of AOSD [

1,

2], constitute Still`s syndrome, a rare polygenic autoinflammatory disorder. The incidence of AOSD is reported to be between 0.1 and 0.4 per 100,000 adults [

3]. While AOSD typically manifests around the age of 35, cases have been recorded where the onset occurs past the age of 70 [

4]. AOSD is associated with a reduced quality of life and substantial economic costs, particularly in patients experiencing significant complications [

5,

6]

AOSD was first described by Bywaters in 1971 [

7] and its primary clinical symptoms include high fever, a transient salmon-colored rash, oligoarticular arthritis or arthralgia, sore throat, and hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly, often accompanied by laboratory abnormalities [

8]. Laboratory findings typically reveal systemic inflammation with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), significantly increased ferritin levels (3-5 times above normal), and leukocytosis, primarily with neutrophilia. Other laboratory variables, including interleukin (IL)-18, glycosylated ferritin, and proteins such as S100A8/A9 and S100A12, are currently under investigation as potential biomarkers but are not routinely evaluated [

9,

10,

11]. Three predominant disease patterns have been identified: a monocyclic course, which typically resolves within a year of presentation with no relapses, a polycyclic course characterized by unpredictable periods of symptoms separated by months or years, and a chronic, progressive course [

8,

12]. Some studies also suggest that AOSD can be grouped into two phenotypes, a systemic form and a chronic articular form that evolves to a disease resembling rheumatoid arthritis [

8,

13].

Despite extensive research, the exact etiology of AOSD remains unknown [

8]. It has been proposed that infections or cellular stress lead to an activation of the innate immune system via pathogen-associated molecular patterns or damage-associated molecular patterns. These events, in turn, result in the production of alarmins (e.g., S100 proteins) and the subsequent overproduction of key inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and IL-18 [

10,

11,

14]. If this process is not adequately controlled, chronic inflammation may ensue, leading to a transition from systemic inflammation to a chronic arthritis-driven form of the disease that is sustained by the adaptive immune system [

11,

15].

Diagnosis of AOSD can be difficult and is often delayed. A recent study reported that the mean time from first symptoms to AOSD diagnosis in German rheumatology clinics was 15.6 months [

16], and other centers have reported similar delays [

13], although the length varies widely by site. Diagnosis is typically based on a combination of clinical and laboratory findings and requires the exclusion of infections, malignancies, and other inflammatory conditions, including macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, vasculitides, and other periodic fever syndromes [

8,

10,

17,

18,

19]. Rare but severe complications of AOSD include MAS [

20,

21], lung disease [

22,

23], and amyloidosis in cases of chronic inflammation [

24].

The development of therapy and treat-to-target (T2T) protocols for AOSD has been challenging due to a need for larger and more rigorous comparative studies of treatment options in AOSD as well as for standardized definitions of a therapeutic response [

1]. Although disease activity scores have been applied to AOSD, particularly the Pouchot score [

25,

26] and Still Activity Score (SAS) [

27], there is currently no consensus efficacy outcome measure [

28] and disease activity measures are not uniformly used in clinical studies [

29]. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) has recently developed an AOSD disease activity score, the DAVID score [

30], which may allow more consistent assessments of AOSD and better characterization of treatment responses.

Recently released joint EULAR and Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) guidelines recommend IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra or canakinumab) or IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) inhibitors (tocilizumab) for patients with sJIA/AOSD; for patients with high disease activity, concomitant glucocorticoids may be required to achieve disease control and tapered when possible [

1]. Similar management recommendations have been made by an expert panel [

31]. The German Society of Rheumatology S2 guidelines are generally consistent with these other recommendations [

32]. However, one key difference is that the EULAR/PReS guidelines prioritize IL-1 and IL-6R inhibitors over conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate (MTX), for glucocorticoid-sparing and initial therapies regardless of disease activity [

1], whereas the German Society of Rheumatology S2 guidelines include MTX or calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine) along with IL-1 and IL-6R inhibitors as considerations for glucocorticoid-sparing first-line agents in patients with mild disease activity [

32]. The ultimate goal of treatment is drug-free remission with no AOSD-related symptoms and normal levels of CRP and ESR [

1].

This study aimed to retrospectively collect and analyze data from multiple rheumatology centers across Germany to better understand the clinical presentation, disease activity, and treatment outcomes in patients with AOSD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study was a retrospective analysis of data obtained from patients with AOSD seen at German rheumatology centers in the following cities: Augsburg, Bad Bramstedt, Erlangen, Freiburg, Gomemrn, Herne, Kirchheim Teck, Köln, Planegg, and Tübingen. The primary goal of the study was to descriptively evaluate current AOSD characteristics and management practices in Germany. All included patients had a confirmed diagnosis of AOSD according to the validated Yamaguchi criteria [

33,

34], the diagnostic criteria recommended by the German Society of Rheumatology S2 guidelines [

32], at the time of data collection (between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020), or documentation of a disease recurrence. Patients were required to be adults at the time of data collection and willing to provide pseudonymized data. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. Data for current status were collected at a single visit; medical records were used to obtain data on status at initial diagnosis and therapies that had ever been received.

Data collection was conducted following approval by the central ethics committee of Erlangen University (Ethics Approval: 365_20 Bc), and the data were anonymized to ensure patient confidentiality. All patients provided informed consent.

2.2. Outcomes

The evaluated patient variables were based on data entered by the clinician during routine clinical practice. Patient data included demographic features, clinical manifestations, the presence of comorbidities associated with the disease or its treatment (e.g., MAS, osteoporosis, diabetes, hypertension, fractures), and disease pattern (monocyclic, polycyclic, or chronic). Disease activity was assessed using the Pouchot score ranging from 0 to 12 [

25,

26] and the Still Activity Score (SAS) ranging from 0 to 7 [

27], which were calculated based on symptoms, organ involvement, and laboratory values. For both scales, lower scores indicate less disease activity. Medical records were used to extract data on these outcomes at the time of initial diagnosis to allow evaluation of the disease course over time. Patient-reported global disease activity (PtGA) was measured by a visual analog scale (VAS) on a scale of 0 (best) to 10 (worst). Patient satisfaction with therapy was measured on a VAS from 0 (worst) to 10 (best). Current treatment strategies as well as AOSD therapies that were ever received were reported. Laboratory values used for diagnosis, specifically ferritin ≥350 ng/mL and neutrophils ≥65%, were also evaluated. The database did not include additional laboratory values, such as ESR or CRP.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

As this was an exploratory study, sample size calculations were not performed; the sample size was based on all patients who met the inclusion criteria. Descriptive data, including number with percentages and means with standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for specified observed outcomes. Missing data were not imputed.

3. Results

Ten centers and 120 AOSD patients participated in the study. Over half (55.8%) of patients were female and 44.2% were male (

Table 1). The mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 41.4 (16.8) years and the mean (SD) current age was 50.7 (16.2) years. The mean (SD) time from diagnosis was 9.4 (6.9) years. Most patients (71.7%) were being seen at the rheumatology center as a follow-up visit following an earlier diagnosis, while 28.3% were being seen due to a disease recurrence. The most common disease course was polycyclic (55.0%), followed by chronic (24.1%) and monocyclic (20.8%). The most common current comorbidities were arterial hypertension (16.7%), MAS (10.0%), osteoporosis (8.3%), and diabetes mellitus (6.7%) The mean (SD) Pouchot score at initial diagnosis was 5.1 (2.0) on a scale of 0 to 12, indicating moderate disease activity (

Table 1).

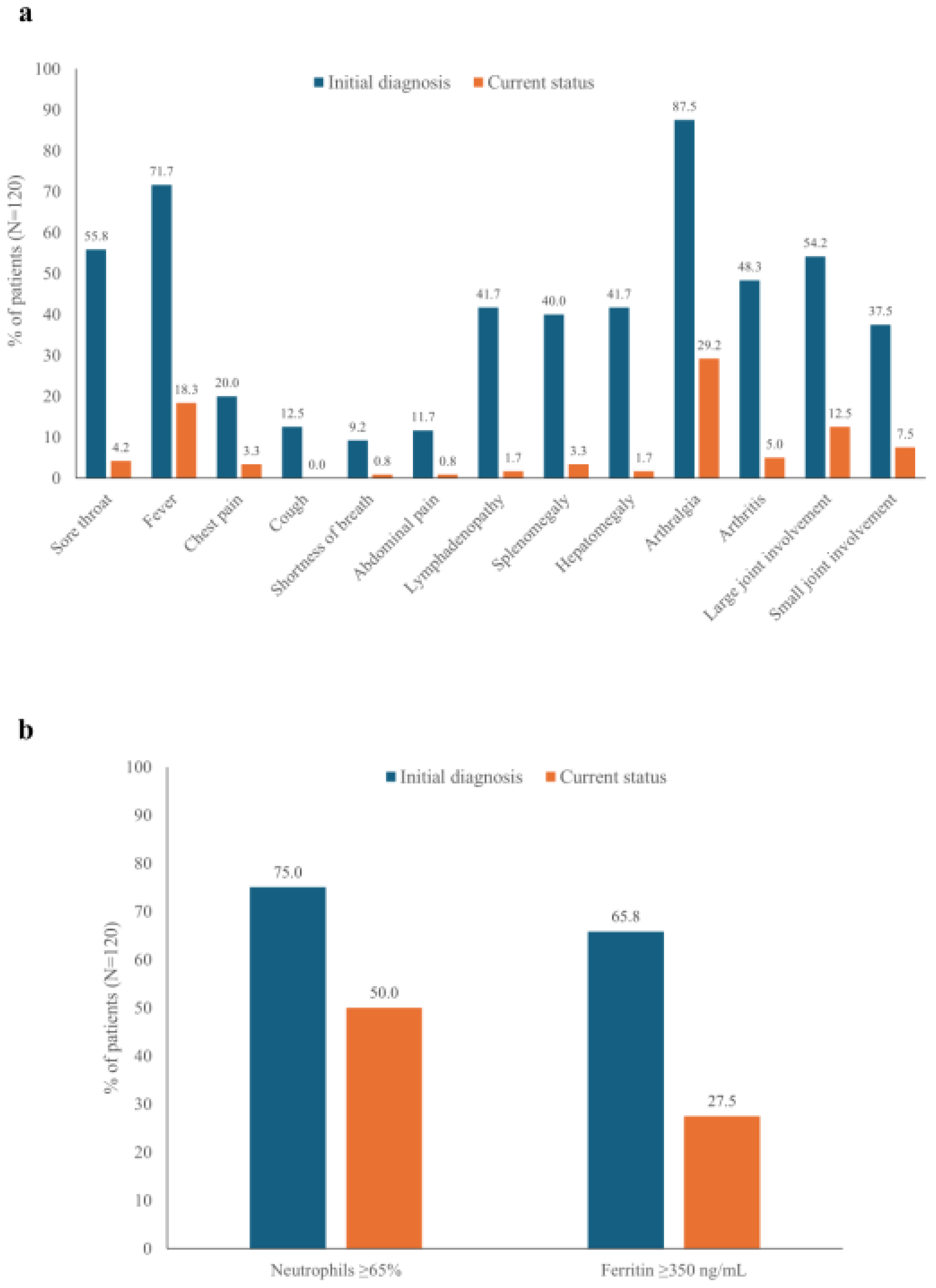

3.1. Symptoms and Laboratory Findings: Initial Diagnosis vs Current Status

Arthralgia was the most frequent symptom at initial diagnosis (87.5%), and a substantial proportion of patients (29.2%) continued to experience arthralgia at the most recent followup (

Figure 1A). Large joint involvement was more common than small joint involvement at both initial diagnosis and follow-up. Fever was observed in 71.7% of patients at initial diagnosis and 18.3% at follow-up. Other common symptoms at initial diagnosis, such as sore throat, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly, had resolved in most patients at the most recent follow-up (

Figure 1A).

High neutrophil (≥65%) and ferritin (≥350 ng/mL) levels were common in patients at the initial diagnosis (75.0% and 65.8%, respectively) (

Figure 1B). Although both were reduced at the most recent follow-up, a substantial proportion of patients continued to experience high neutrophil or ferritin levels (50.0% and 27.5%, respectively).

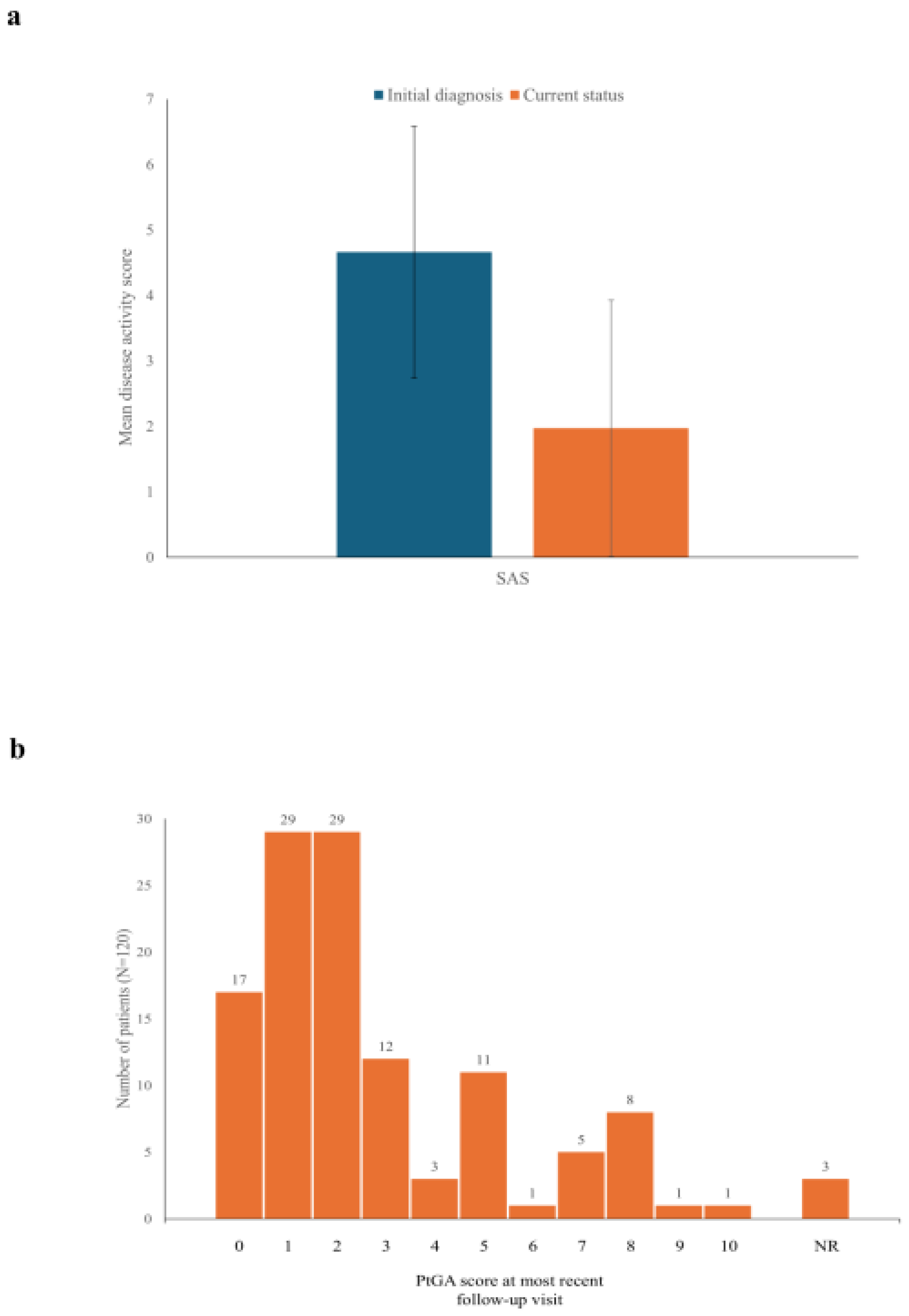

3.2. Disease Activity: Initial Diagnosis vs Current Status

At the initial diagnosis, the mean (SD) SAS was 4.7 (1.9) on a scale of 0 to 7 (

Figure 2A), consistent with the moderate disease activity indicated by the Pouchot score (5.1 [2.0];

Table 1). The SAS value fell to 2.0 (2.0) at the most recent follow-up (

Figure 2A). More than one-quarter of patients (34; 28.3%) were in remission (SAS=0) at their most recent follow-up. Data were not available for the Pouchot score at the most recent visit, as this score is based in part on work-ups performed to exclude other conditions, which are not routinely performed.

PtGA assessments were collected at the most recent follow-up, but not at the initial diagnosis. These values indicated low disease activity for most patients at the current time (mean [SD] of 2.7 [2.5] on a 10-point VAS), with most patients having scores ≤2 (

Figure 2B). Seventeen patients (14.2%) reported a PtGA score of 0. However, 10 patients (8.3%) reported PtGA scores ≥8, indicating that some patients continued to experience high disease activity. In general, there was good concordance between PtGA scores and SAS values. For instance, all of the 17 patients with a PtGA score of 0 had an SAS of 2 or lower.

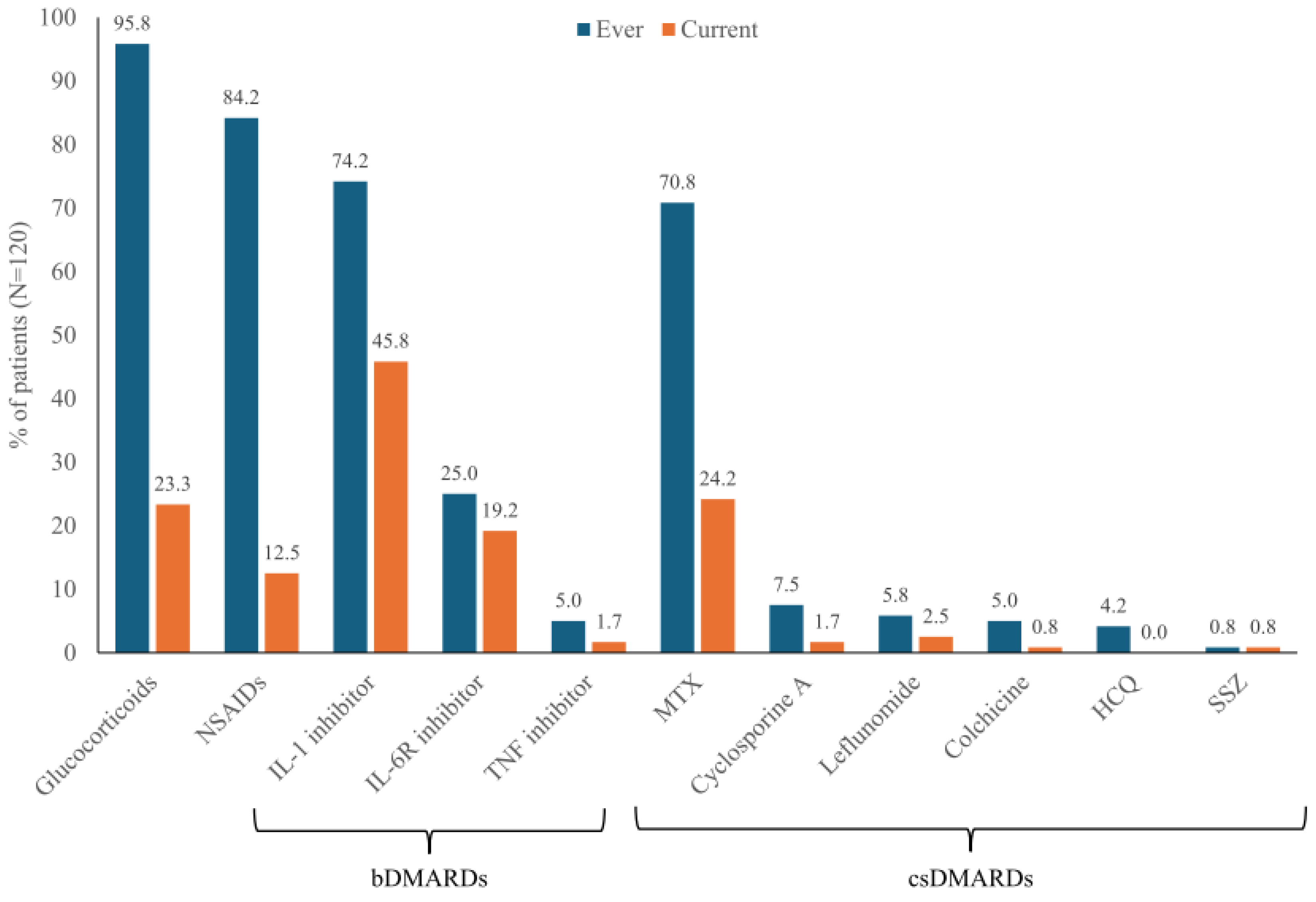

3.3. Drug Therapies and Satisfaction with Treatment

Glucocorticoids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) had been used in almost all patients at some point during their disease (95.8% and 84.2%, respectively), but at the most recent follow-up these drugs were used by only 23.3% and 12.5%, respectively (

Figure 3). IL-1 inhibitors were the most frequently used bDMARD (74.2% ever and 45.8% currently) and MTX was the most frequently used csDMARD (70.8% ever, 24.2% currently). IL-6R inhibitors were also employed (25.0% ever, 19.2% currently). TNF inhibitors and csDMARDs other than MTX were less commonly used (current therapy for <5% of patients) (

Figure 3).

Patient satisfaction with therapy at the last followup was a mean (SD) of 6.63 (3.20) on a 10-point VAS scale ranging from 0=worst to 10=best (N=99; no data were available for 21 patients). Twenty-three patients (19.2%) rated their satisfaction as 10, the highest level.

4. Discussion

This study of 120 patients with AOSD seen at German rheumatology centers documents the heavy comorbidity and symptom burden of this disease, particularly at the time of initial diagnosis. As has been observed in other cohorts [

13,

35,

36,

37], fever and arthralgia were the most common symptoms at initial diagnosis, affecting 71.7% and 87.5% of patients, respectively. Although there were strong improvements in symptoms from initial diagnosis to the visit at which data were collected, 18.9% of patients continued to have a fever and 29.2% had arthralgia. The high numbers of patients with elevated neutrophil (50.0%) and ferritin (27.5%) levels also suggested ongoing disease activity in some patients.

Consistent with the changes observed in symptoms, the SAS showed marked improvements in disease activity from initial diagnosis to current status. Based on SAS, 28.3% of patients were in remission at the time point for which data were reported. PtGA values also supported low mean disease activity at the most recent visit for most patients. PtGA scores at the current visit were generally concordant with SAS scores.

Our findings indicate a high usage of MTX (70.8%) at the time of the initial diagnosis, a practice that is in line with German Society of Rheumatology guidelines [

32] but is not considered the preferred treatment path by current EULAR/PReS guidelines [

1] based on a systematic review of bDMARDs in AOSD [

38]. IL-1 inhibitors were also used frequently at the time of initial diagnosis (74.2%) and were more likely to be reported as treatment at the most current visit (45.8% vs 24.2% for MTX). It should be emphasized that our study time period preceded dissemination of the most recent guidelines on treatment management by these organizations, so it is likely that some of the treatment patterns we observed have changed in the intervening years. Part of our data also preceded the European Medicines Agency approval of IL-1 inhibitors for AOSD (canakinumab in 2016 [

39], anakinra in 2018 [

40]), which may explain why only 90 out of 120 patients had ever received IL-1 inhibition. However, studies spanning data from more recent years have also observed a high use of csDMARDs in AOSD patients. A retrospective study of 168 patients diagnosed with AOSD between 2007 and 2023 found that after publication of the German AOSD guidelines, time to diagnosis was shorter and treatment side effects were lower, but therapeutic approaches did not change substantially over time [

16]. Similarly, a recent German study including data from 2007 through 2022 found that only about half of the included AOSD patients (44/86 [51.2%]) had received initial therapy with a bDMARD [

41]. These findings are consistent with a survey of 11 European AOSD experts (from Italy, the UK, France, and Germany) conducted in 2022, which found that most clinicians initated treatment with glucocorticoids and used csDMARDs as second-line treatment and bDMARDs as third-line treatment [

42].

Together, these findings on treatment patterns suggest that rheumatologists and other clinicians may require additional education on changing therapeutic paradigms for AOSD, particularly with respect to IL-1 and IL-6R inhibitors as effective tools in the management of this disorder. It is hoped that new treatment strategies, including T2T approaches, could improve long-term outcomes [

1,

43]. A T2T approach to therapy has been proposed in the recent EULAR guidelines for AOSD [

1] and is already considered the standard of care for sJIA [

44,

45,

46] on the basis of studies indicating superior responses in sJIA patients treated with T2T strategies, particularly in those receiving biologic therapies, although head-to-head trials are lacking [

47,

48]. Although evidence for the use of T2T strategies in AOSD has lagged somewhat due in part to a lack of consensus on outcome measures for response, given that sJIA and AOSD are now considered part of the same disease continuum the application of T2T approaches to adults seems a reasonable extension of its use in pediatric patients. Furthermore, a recent study found that initial bDMARD therapy is associated with a more than 7-fold increase in the probability of achieving sustained, event-free remission compared with AOSD patients who do not receive initial bDMARD therapy [

41]. These data suggest that early initiation of aggressive treatment along with a T2T approach may result in more favorable long-term outcomes.

The differences in adoption of T2T in sJIA and AOSD are mirrored in other facets of disease management for these two disorders, including assessments of symptoms and treatment response. A recent literature review of 195 articles found wide heterogeneity in data reporting across the spectrum of sJIA and AOSD, and even within each disease type (sJIA or AOSD) [

29]. Diagnostic criteria and disease activity measurements varied based on age and study, and reporting of symptoms and laboratory values lacked uniformity. For instance, arthralgia was evaluated in 12.0% of sJIA studies and in 68.8% of AOSD studies. These variations are understandable given that our awareness of these two disorders as part of the same spectrum is relatively recent, but serve as a hindrance to a more complete picture of disease manifestations and response over time and to efforts to compare outcomes across different studies.

Along with standardized forms of assessment, the identification and incorporation of conventional and novel biomarkers into diagnostic and therapeutic models may also help advance patient care [

2,

13]. Early studies suggest that the inclusion of biomarkers in outcome prediction models may improve evaluations of disease activity [

49,

50]. Although several biomarkers appear to be shared across sJIA and AOSD, particularly ferritin, S100 proteins, and IL-18 [

2], additional studies are needed to assess the robustness of these indicators and the potential benefits of including them in clinical trials to assess responses to new therapies as well as in everyday clinical practice.

Educational efforts involving the prompt diagnosis of AOSD may also be of value. In Germany and elsewhere, the time from symptoms to AOSD diagnosis has been reported to be longer than 1 year [

13,

16]. Delayed diagnosis or treatment may result in a missed therapeutic "window of opportunity," potentially resulting in long-term damage [

51,

52]. In one study, AOSD patients with a delayed diagnosis (>6 months) were more likely to experience a chronic disease course [

36].

Limitations of this study include low patient numbers related to limited participation by German rheumatology centers, perhaps due to time constraints or inadequate reimbursement. Conclusions from this study were also limited by the retrospective study design and the use of only one visit for data collection. Patients with a monocyclic disease course may have been underrepresented in our study, as those with fully resolved disease may not have needed additional rheumatology visits. Our database did not include levels of inflammatory markers, such as CRP or ESR; these would be valuable additions for future studies.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective study suggests that AOSD patients in Germany seen during routine clinical care show fewer symptoms and lower disease activity than at initial diagnosis, but the burden of disease remains high in some patients, and more advanced treatment options may be under-utilized. Future studies will be required to explore symptoms, disease activity, and outcomes following new treatment recommendations.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S., S.W., J.H., E.F., N.T.B., F.P., M.S.H., B.H., I.K., I.A., J.R; Methodology, V.S., S.W., J.H., E.F., N.T.B., F.P., M.S.H., B.H., I.K., I.A., J.R.; Validation, V.S., S.W., J.H., E.F., N.T.B., F.P., M.S.H., B.H., I.K., I.A., J.R; Resources, V.S., S.W., J.H., E.F., N.T.B., F.P., M.S.H., B.H., I.K., I.A., J.R; Data Curation, V.S., S.W., J.H., E.F., N.T.B., F.P., M.S.H., B.H., I.K., I.A., J.R; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.R.; Writing—Review & Editing, V.S., S.W., J.H., E.F., N.T.B., F.P., M.S.H., B.H., I.K., I.A., J.R; Visualization, J.R.; Supervision, V.S., I.A., J.R.; Project Administration, J.R.; Funding Acquisition, J.R.

Funding

This research was funded by research grants from Novartis Pharma GmbH and Swedish Orphan Biovitrium GmbH (Sobi).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the central ethics committee of Erlangen University (Ethics Approval: 365_20 Bc), and the data were anonymized to ensure patient confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and medical staff who participated in this study and Sharon L. Cross, who provided medical writing support under the direction of and with funding from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

V.S. received honoraria for lectures and/or consultation services and unrestricted grants from Chugai and Novartis. J.H. received fees for speaker bureau participation and unrestricted grants from Novartis, Sobi, and Chugai. E.F. received honoraria from AbbVie, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Medac, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sobi, and UCB. B.H. received honoraria for lectures and/or consultation services from Chugai, Amgen, and Novartis. I.K received honoraria for advisory boards and speaker fees from Novartis and Sobi. I.A. received consulting fees and honoraria from Novartis and Sobi and participated on a Data Safety Monitoring or Advisory Board for Novartis and Sobi. J.R. received grants from Novartis and Sobi and speaker and/or consultancy fees from AbbVie, Biogen, BMS, Chugai, GSK, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Sobi, and UCB. S.W., N.T.B, F.P., and M.S.-H. declare no conflicts of interest in relation to the manuscript. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Fautrel, B.; Mitrovic, S.; De Matteis, A.; Bindoli, S.; Antón, J.; Belot, A.; Bracaglia, C.; Constantin, T.; Dagna, L.; Di Bartolo, A.; et al. EULAR/PReS recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Still’s disease, comprising systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still’s disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, A.; Bindoli, S.; De Benedetti, F.; Carmona, L.; Fautrel, B.; Mitrovic, S. Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still's disease are the same disease: evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses informing the 2023 EULAR/PReS recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Still's disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerfaud-Valentin, M.; Jamilloux, Y.; Iwaz, J.; Seve, P. Adult-onset Still's disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, T.; Zoshima, T.; Takeji, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Mizushima, I.; Yamada, K.; Nakashima, A.; Yachie, A.; Kawano, M. Elderly-onset Still's disease complicated by macrophage activation syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscitti, P.; Feist, E.; Canon-Garcia, V.; Rabijns, H.; Toennessen, K.; Bartlett, C.; Gregg, E.; Miller, P.; McGonagle, D. Burden of adult-onset Still’s disease: A systematic review of health-related quality of life, utilities, costs and resource use. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2023, 63, 152264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, S.; Schroeder, B.; Alfaki, M. Mortality, length of stay and cost of hospitalization among patients with adult-onset Still's disease: Results from the National Inpatient Sample 2016-2019. Diseases. 2024, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywaters, E.G. Still's disease in the adult. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1971, 30, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaras, S.; Goetzke, C.C.; Kallinich, T.; Feist, E. Adult-onset Still’s disease: Clinical aspects and therapeutic approach. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priori, R.; Colafrancesco, S.; Alessandri, C.; Minniti, A.; Perricone, C.; Iaiani, G.; et al. Interleukin 18: a biomarker for differential diagnosis between adult-onset Still's disease and sepsis. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 41, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feist, E.; Mitrovic, S.; Fautrel, B. Mechanisms, biomarkers and targets for adult-onset Still's disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föll, D.; Wittkowski, H.; Hinze, C. Das Still-Syndrom als biphasische Erkrankung: Aktuelle Erkenntnisse zur Pathogenese und neue therapeutische Ansätze [Still's disease as biphasic disorder : Current knowledge on pathogenesis and novel treatment approaches]. Z. Rheumatol. 2020, 79, 639–648, German. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cush, J.J.; Medsger Jr., T. A.; Christy, W.C.; Herbert, D.C.; Cooperstein, L.A. Adult-onset Still's disease. Clinical course and outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 1987, 30, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthimiou, P.; Kontzias, A.; Hur, P.; Rodha, K.; Ramakrishna, G.S.; Nakasato, P. Adult-onset Still’s disease in focus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and unmet needs in the rra of targeted therapies. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 51, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Suh, C.H.; Kim, H.A. Roles of interactions between toll-like receptors and their endogenous ligands in the pathogenesis of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still's disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigrovic, PA. Review: is there a window of opportunity for treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis? Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, R.; Kernder, A.; Blank, N.; Ernst, D.; Henes, J., Keyßer, G., Klemm, P.; Krusche, M.; Meinecke, A.; Rech, J.; et al. Implementation of the new DGRh S2e guideline on diagnostics and treatment of adult-onset Still's disease in Germany. Implications for clinical practice in rheumatology. Z. Rheumatol. 2024, Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Crispin, J.C.; Martinez-Banos, D.; Alcocer-Varela, J. Adult-onset Still disease as the cause of fever of unknown origin. Medicine 2005, 84, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sautner, J. Makrophagenaktivierungssyndrom – eine seltene Komplikation bei adultem Morbus Still. Rheuma Plus. 2020, 19, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerlecken, N.T.; Schmidt, R.E. Adulter Morbus Still, Fieber, Diagnose und Therapie [Adult onset Still's disease, fever, diagnosis and therapy]. Z. Rheumatol. 2012, 71, 174–180, German. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M. Macrophage activation syndrome associated with adult-onset Still's disease. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 2007, 30, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigante, D.; Emmi, G.; Fastiggi, M.; Silvestri, E.; Cantarini, L. Macrophage activation syndrome in the course of monogenic autoinflammatory disorders. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 34, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saper, V.E.; Chen, G.; Deutsch, G.H.; Guillerman, R.P.; Birgmeier, J.; Jagadeesh, K.; Canna, S.; Schulert, G.; Deterding, R.; Xu, J.; et al.; Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Registry Investigators. Emergent high fatality lung disease in systemic juvenile arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 1722–1731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscitti, P.; Bruno, F.; Berardicurti, O.; Acanfora, C.; Pavlych, V.; Palumbo, P.; Conforti, A.; Carubbi, F.; Di Cola, I.; Di Benedetto, P.; et al. Lung involvement in macrophage activation syndrome and severe COVID-19: results from a cross-sectional study to assess clinical, laboratory and artificial intelligence-radiological differences. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 1152–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantarogh, S.; Vilaiyuk, S.; Tim-Aroon, T.; Worawichawong, S. Clinical improvement of renal amyloidosis in a patient with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis who received tocilizumab treatment: a case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouchot, J.; Sampalis, J.S.; Beaudet, F.; Carette, S.; Décary, F.; Salusinsky-Sternbach, M.; Hill, R.O.; Gutkowski, A.; Harth, M.; Myhal, D.; et al. Adult Still's disease: manifestations, disease course, and outcome in 62 patients. Medicine. 1991, 70, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, M.; Schiller, M.; Krienke, S.; Heyder, P.; Lorenz, H.; Blank, N. Clinical manifestations but not cytokine profiles differentiate adult-onset Still's disease and sepsis. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyoncu, U.; Kasifoglu, T.; Omma, A.; Bes, C.; Cinar, M.; Emmungil, H.; Kucuksahin, O.; Akar, S.; Aksu, K.; Yildiz, F.; et al. Derivation and validation of adult Still Activity Score (SAS). Joint Bone Spine. 2023, 90, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindoli, S.; De Matteis, A.; Mitrovic, S.; Fautrel, B.; Carmona, L.; De Benedetti, F. Efficacy and safety of therapies for Still's disease and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS): a systematic review informing the EULAR/PReS guidelines for the management of Still's disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1731–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia Marques, M.; Balay-Dustrude, E.; Bracaglia, C.; Twilt, M.; Onel, K.; Appenzeller, S.; Dedeoglu, F.; Eloseily, E.; Martinez Jimenez, P.; Trachtman. R.; et al. Reporting of clinical features and outcome measures in Still’s disease: A systematic literature review of sJIA and AOSD cohorts [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76 (suppl 9), abstract 0402. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/reporting-of-clinical-features-andoutcome-measures-in-stills-disease-a-systematic-literature-review-of-sjia-and-aosd-cohorts/.

- Ruscitti, P., Stamm, T., Ritschl, V., Mitrovic, S., Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., Alexanderson, H., Barten, B., Bostrøm, C., Fell, D., Gattorno, M., et al. The development of the EULAR Score for the definition of disease activity in adult-onset Still’s sisease; The “DAVID” Project [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76 (suppl 9), abstract 2030. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/the-development-of-the-eular-score-for-the-definition-of-disease-activity-in-adult-onset-stills-disease-the-david-project/.

- Leavis, H.L.; van Daele, P.L.A.; Mulders-Manders, C.; Michels, R.; Rutgers, A.; Legger, E.; Bijl, M.; Hak, E.A.; Lam-Tse, W.K.; Bonte-Mineur, F.; et al. Management of adult-onset Still's disease: evidence- and consensus-based recommendations by experts. Rheumatology. 2024, 63, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vordenbäumen, S.; Feist, E.; Rech, J.; Fleck, M.; Blank, N.; Haas, J.-P.; Kötter, I.; Krusche, M.; Chehab, G.; Hoyer, B.; et al. DGRh-S2e-Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie des adulten Still-Syndroms (AOSD). Z. Rheumatol. 2022, 81, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Ohta, A.; Tsunematsu, T.; Kasukawa, R.; Mizushima, Y.; Kashiwagi, H.; Kashiwazaki, S.; Tanimoto, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ota, T.; et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J. Rheumatol. 1992, 19, 424–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun, D.; Mestrallet, S.; Dehoux, M.; Golmard, J.L.; Granger, B.; Georgin-Lavialle, S.; Arnaud, L.; Grateau, G.; Pouchot, J.; Fautrel, B. Validation of the Fautrel Classification Criteria for Adult-Onset Still’s Disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 47, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, S.; Dagna, L.; Salvo, F.; Aiello, P.; Baldissera, E.; Sabbadini, M.G. Adult onset Still's disease: clinical presentation in a large cohort of Italian patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalyoncu, U.; Solmaz, D.; Emmungil, H.; Yazici, A.; Kasifoglu, T.; Kimyon, G.; Balkarli, A.; Bes, C.; Ozmen, M.; Alibaz-Oner, F.; et al. Response rate of initial conventional treatments, disease course, and related factors of patients with adult-onset Still’s disease: Data from a large multicenter cohort. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 69, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscitti, P.; Natoli, V.; Consolaro, A.; Caorsi, R.; Rosina, S.; Giancane, G.; Naddei, R.; Di Cola, I.; Di Muzio, C.; Berardicurti, O.; et al. Disparities in the prevalence of clinical reatures between systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still’s disease. Rheumatology. 2022, 61, 4124–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fautrel, B.; Patterson, J.; Bowe, C.; Arber, M.; Glanville, J.; Mealing, S.; Canon-Garcia, V.; Fagerhed, L.; Rabijns, H.; Giacomelli, R. Systematic review on the use of biologics in adult-onset Still’s disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2023, 58, 152139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Summary of opinion (post authorization): Ilaris (canakinumab). 23 June 2016. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop/chmp-post-authorisation-summary-positive-opinion-ilaris_en.pdf-1 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Sobi. Kineret® (anakinra) approved in the EU for the treatment of Still’s disease. 11 April 2018. Available online: https://www.sobi.com/sites/sobi/files/pr/201804107653-1.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Kernder, A.; Filla, T.; Friedrich, R.; Blank, N.; Ernst, D.; Henes, J.; Keyßer, G.;, Klemm, P.; Krusche, M.; et al. First-line biological vs. conventional therapy in adult-onset Still’s disease: a multicentre, retrospective, propensity weighted analysis. Manuscript submitted. Preprint available at. [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Gregg, E.; Canon-Garcia, V.; Rabijns, H.; Toennessen, K.; Bartlett, K.; Graziadio, S. Care pathway analysis and evidence gaps in adult-onset Still’s disease: Interviews with experts from the UK, France, Italy, and Germany. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1257413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, C.H.; Holzinger, D.; Lainka, E; Haas, J. P.; Speth, F.; Kallinich, T.; Rieber, N.; Hufnagel, M.; Jansson, A.F.; Hedrich, C.; et al. PRO-KIND SJIA project collaborators. Practice and consensus-based strategies in diagnosing and managing systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Germany. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2018, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, A.; Consolaro, A.; Horneff, G.; Laxer, R.M.; Lovell, D.J.; Wulffraat, N.M.; Akikusa, J.D.; Al-Mayouf, S.M.; Antón, J.; Avcin, T.; et al. Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tal, T.; Ryan, M.E.; Feldman, B.M.; Bingham, C.A.; Burnham, J.M.; Batthish, M.; Bullock, D.; Ferraro, K.; Gilbert, M. , Gillispie-Taylor, M., et al. Consensus approach to a treat-to-target strategy in juvenile idiopathic arthritis care: Report From the 2020 PR-COIN Consensus Conference. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 49, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onel, K.B.; Horton, D.B.; Lovell, D.J.; Shenoi, S.; Cuello, C.A.; Angeles-Han, S.T.; Becker, M.L.; Cron, R.Q.; Feldman, B.M.; Ferguson, P.J.; et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: therapeutic approaches for oligoarthritis, temporomandibular joint arthritis, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Haar, N.M.; van Dijkhuizen, E.H.P.; Swart, J.F.; van Royen-Kerkhof, A.; El Idrissi, A.; Leek, A.P.; de Jager, W.; de Groot, M.C.H.; Haitjema, S.; Holzinger, D.; et al. Treatment to target using recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist as first-line monotherapy in new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a five-year follow-up study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.; Minden, K.; Hospach, A.; Foeldvari, I.; Weller-Heinemann, F.; Trauzeddel, R.; Huppertz, H.I.; Horneff, G. Treat-to-target study for improved outcome in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, E.; Hogan, D.; Trost, B.; Kusalik, A.J.; Boire, G.; Cabral, D.A.; Campillo, S. ; Chédeville. G.; Chetaille, A.L.; Dancey, P.; et al. Clinical and associated inflammatory biomarker features predictive of short-term outcomes in non-systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glerup, M.; Kessel, C.; Foell, D.; Berntson, L.; Fasth, A.; Myrup, C.; Nordal, E.; Rypdal, V.; Rygg, M.; Arnstad, E.D.; et al.; Nordic Study Group of Paediatric Rheumatology (NoSPeR) Inflammatory biomarkers predicting long-term remission and active disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a population-based study of the Nordic JIA cohort. RMD Open. 2024, 10, e004317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vastert, S.J.; Jamilloux, Y.; Quartier, P.; Ohlman, S.; Osterling Koskinen, L.; Kullenberg, T.; Franck-Larsson, K.; Fautrel, B.; de Benedetti, F. Anakinra in children and adults with Still's disease. Rheumatology. 2019, 58 (Suppl 6), vi9–vi22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindoli, S.; Baggio, C.; Doria, A.; Sfriso, P. Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD): Advances in understanding pathophysiology, genetics and emerging treatment options. Drugs. 2024, 84, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).