Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Analytic Strategy

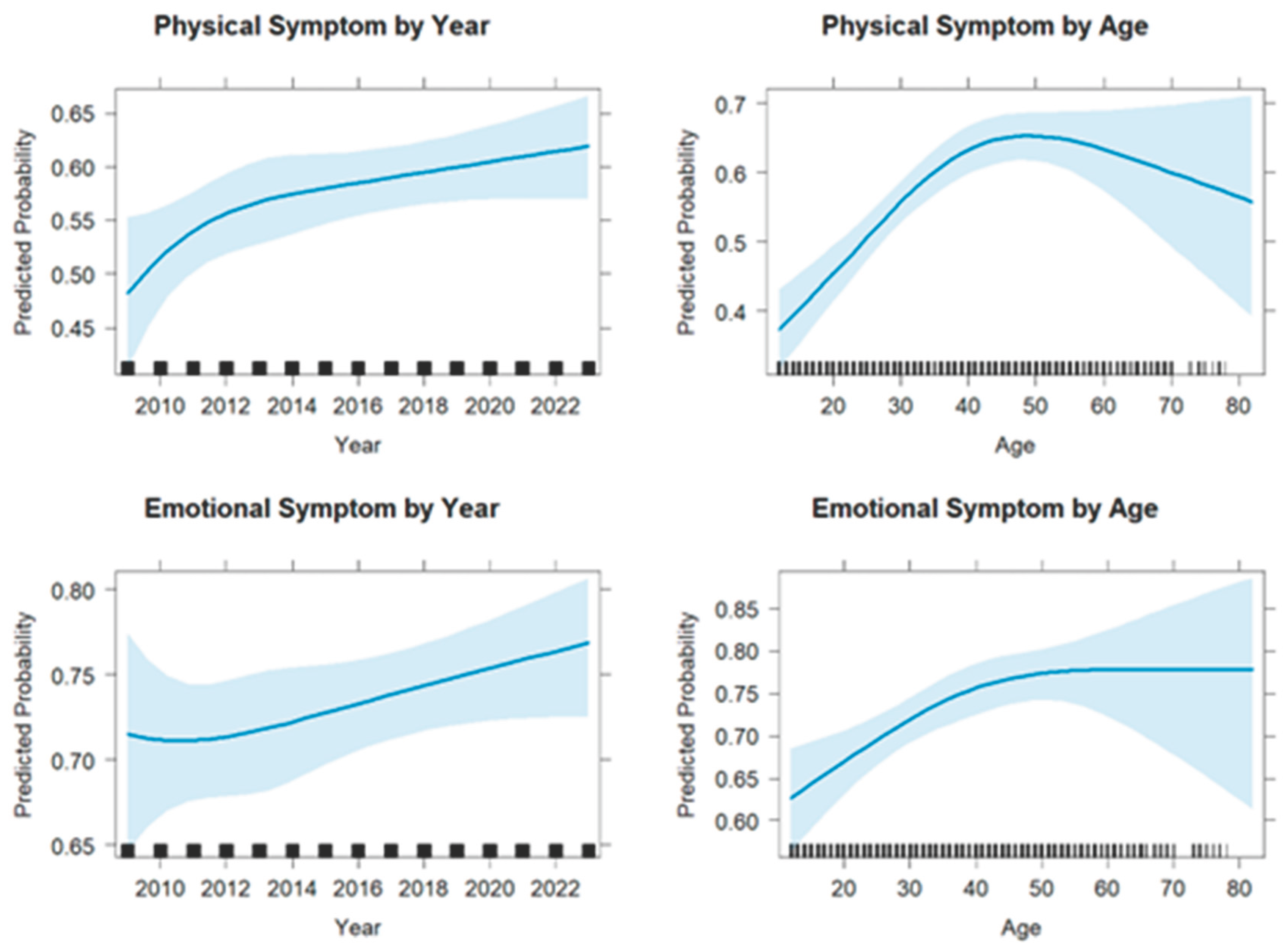

3. Results

4. Discussion

Implications for Proactive Public Health Policy to Support IPV Survivors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPV | Intimate partner violence |

| NCVS | National Crime Victimization Survey |

| BJS | Bureau of Justice Statistics |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| OR | Odds ratio |

References

- Campbell, J.C. Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [CrossRef]

- Carlyle, K.E.; Guidry, J.P.D.; Dougherty, S.A.; Burton, C.W. Intimate Partner Violence on Instagram: Visualizing a Public Health Approach to Prevention. Health Educ. Amp Behav. 2019, 46, 90S-96S. [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.R.; Wilcox, H.C.; Holliday, C.N.; Webster, D.W. An Integrated Public Health Approach to Interpersonal Violence and Suicide Prevention and Response. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 65S-79S. [CrossRef]

- Inslicht, S.S.; Marmar, C.R.; Neylan, T.C.; Metzler, T.J.; Hart, S.L.; Otte, C.; McCaslin, S.E.; Larkin, G.L.; Hyman, K.B.; Baum, A. Increased Cortisol in Women with Intimate Partner Violence-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 825–838. [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, P.; Thoennes, N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the National Violence against Women Survey; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, 2000.

- Plichta, S.B. Intimate Partner Violence and Physical Health Consequences: Policy and Practice Implications. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 1296–1323. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Macy, R.J.; Sullivan, K.; Magee, M.L. Pregnancy-Associated Violent Deaths: The Role of Intimate Partner Violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007, 8, 135–148. [CrossRef]

- Davidov, D.M.; Larrabee, H.; Davis, S.M. United States Emergency Department Visits Coded for Intimate Partner Violence. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 48, 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, B.; Hines, D.A.; Johnson, B.A.; Bates, E.A.; Graham-Kevan, N.; Loder, R.T. Injury Patterns and Associated Demographics of Intimate Partner Violence in Men Presenting to U.S. Emergency Departments. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 48, 298–308. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.B.; Knight, K.E.; Menard, S. Long-Term Consequences of Intimate Partner Abuse on Physical Health, Emotional Well-Being, and Problem Behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 539–570. [CrossRef]

- Schollenberger, J.; Campbell, J.; Sharps, P.W.; O’Campo, P.; Gielen, A.C.; Dienemann, J.; Kub, J. African American HMO Enrollees: Their Experiences with Partner Abuse and Its Effect on Their Health and Use of Medical Services. Violence Women 2003, 9, 599–618. [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, L.; Higley, M.; Hatfield, J.; Surprenant, Z.; Taliaferro, E.; Smith, D.J.; Paolo, A. Survey Results of Women Who Have Been Strangled While in an Abusive Relationship. J. Emerg. Med. 2001, 21, 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Kendall-Tackett, K.A. Inflammation, Cardiovascular Disease, and Metabolic Syndrome as Sequelae of Violence Against Women: The Role of Depression, Hostility, and Sleep Disturbance. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007, 8, 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Leserman, J.; Drossman, D.A. Relationship of Abuse History to Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Symptoms: Some Possible Mediating Mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007, 8, 331–343. [CrossRef]

- Camp, A.R. From Experiencing Abuse to Seeking Protection: Examining the Shame of Intimate Partner Violence. UC Irvine Rev 2022, 13, 103.

- St. Vil, N.M.; Carter, T.; Johnson, S. Betrayal Trauma and Barriers to Forming New Intimate Relationships Among Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP3495–NP3509. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.B.; Knight, K.E.; Menard, S. Long-Term Consequences of Intimate Partner Abuse on Physical Health, Emotional Well-Being, and Problem Behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 539–570. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C. Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. The Lancet 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [CrossRef]

- Plichta, S.B. Intimate Partner Violence and Physical Health Consequences: Policy and Practice Implications. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 1296–1323. [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Spena, P.R.; Marcomini, I.; Poliani, A.; Rosa, D.; Maculotti, D.; Manara, D.F. Factors Influencing the Feeling of Shame in Individuals with Incontinence: The INCOTEST Study. Kontakt 2025, 27, 97–102. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, A.; Szoeke, C. The Effect of Intimate Partner Violence on the Physical Health and Health-Related Behaviors of Women: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022, 23, 1157–1172. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics National Crime Victimization Survey, 2022–2009.

- Wheeler, A.P.; Piquero, A.R. Using Victimization Reporting Rates to Estimate the Dark Figure of Crime: A Case Study of Domestic Violence. Crime Delinquency 2025, 00111287251359210. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.W.; Hemenway, D. Emotional and Physical Symptoms after Gun Victimization in the United States, 2009–2019. Prev. Med. 2021, 143, 106374. [CrossRef]

- 25. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Lumley, T. Survey: Analysis of Complex Survey Samples 2023.

- Harrell Jr, F.E. Rms: Regression Modeling Strategies; 2023.

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation; 2023.

- Wickham; Chang, W.; Pedersen, T.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics 2018.

- Golding, J.M. Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J. Fam. Violence 1999, 14, 99–132. [CrossRef]

- Hullenaar, K.L.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Rivara, F.P.; Vavilala, M.S.; Baumer, E.P. Victim–Offender Relationship and the Emotional, Social, and Physical Consequences of Violent Victimization. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, 763–769. [CrossRef]

- Kendall-Tackett, K.A. Inflammation, Cardiovascular Disease, and Metabolic Syndrome as Sequelae of Violence Against Women: The Role of Depression, Hostility, and Sleep Disturbance. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007, 8, 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Orpinas, P.; Choi, Y.J.; Han, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Ahn, K. Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: Barriers to Seeking Help Among Asian Immigrants. J. Evid.-Based Soc. Work 2025, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Black, M.C. Intimate Partner Violence and Adverse Health Consequences: Implications for Clinicians. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2011, 5, 428–439. [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Edwards, V.J.; Croft, J.B. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Personal Alcohol Abuse as an Adult. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 713–725. [CrossRef]

- Esopenko, C.; Jain, D.; Adhikari, S.P.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Ellis, M.; Haag, H. (Lin); Hovenden, E.S.; Keleher, F.; Koerte, I.K.; Lindsey, H.M.; et al. Intimate Partner Violence-Related Brain Injury: Unmasking and Addressing the Gaps. J. Neurotrauma 2024, 41, 2219–2237. [CrossRef]

- Houry, D.; Sachs, C.J.; Feldhaus, K.M.; Linden, J. Violence-Inflicted Injuries: Reporting Laws in the Fifty States. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2002, 39, 56–60. [CrossRef]

- Haag, H. (Lin); Jones, D.; Joseph, T.; Colantonio, A. Battered and Brain Injured: Traumatic Brain Injury Among Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence—A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022, 23, 1270–1287. [CrossRef]

- Lahav, Y.; Avidor, S.; Gafter, L.; Lotan, A. A Double Betrayal: The Implications of Institutional Betrayal for Trauma-Related Symptoms in Intimate Partner Violence Survivors. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2025. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Montilla, C.; Lozano, L.M.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; Valor-Segura, I.; Padilla, J.-L. Understanding the Components and Determinants of Police Attitudes Toward Intervention in Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2023, 24, 245–260. [CrossRef]

- Isman, K.; Giorgi, S.; Ellis, J.; Huhn, A.S.; Liu, T.; Curtis, B. Perceived Stigma and Its Impact on Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health 2024.

| Characteristic | Level | Denom N (unwtd) |

Denom N (wtd) |

Emotional n (unwtd) |

Emotional n (wtd) |

Emotional % (wtd) |

Physical n (unwtd) |

Physical n (wtd) |

Physical % (wtd) |

| Overall | All | 3,012 | 7,650,471 | 2,186 | 5,403,579 | 70.6 | 1,737 | 4,098,268 | 53.6 |

| Age | Under 19 | 302 | 1,027,762 | 185 | 617,999 | 60.1 | 119 | 379,341 | 36.9 |

| 19–39 | 1,693 | 4,410,926 | 1,227 | 3,141,339 | 71.2 | 976 | 2,380,037 | 54.0 | |

| 40–59 | 883 | 1,969,251 | 670 | 1,464,416 | 74.4 | 559 | 1,194,755 | 60.7 | |

| 60+ | 134 | 242,533 | 104 | 179,825 | 74.1 | 83 | 144,134 | 59.4 | |

| Race | Asian/PI | 56 | 155,529 | 46 | 126,607 | 81.4 | 43 | 112,920 | 72.6 |

| Black | 469 | 1,331,715 | 346 | 931,464 | 69.9 | 261 | 624,699 | 46.9 | |

| Hispanic | 492 | 1,304,346 | 357 | 933,534 | 71.6 | 270 | 648,830 | 49.7 | |

| White | 2,290 | 5,609,273 | 1,650 | 3,940,214 | 70.2 | 1,314 | 3,048,489 | 54.3 | |

| Multiracial | 145 | 428,951 | 102 | 307,380 | 71.7 | 82 | 226,389 | 52.8 | |

| Sex | Male | 668 | 1,800,398 | 372 | 949,016 | 52.7 | 237 | 558,707 | 31.0 |

| Female | 2,344 | 5,850,073 | 1,814 | 4,454,563 | 76.1 | 1,500 | 3,539,560 | 60.5 | |

| Highest Level of Education | HS diploma | 1,273 | 3,297,484 | 908 | 2,298,845 | 69.7 | 704 | 1,705,277 | 51.7 |

| > HS diploma | 1,720 | 4,311,041 | 1,260 | 3,065,499 | 71.1 | 1,019 | 2,366,506 | 54.9 | |

| Injury | No | 2,882 | 7,315,829 | 2,076 | 5,126,300 | 70.1 | 1,639 | 3,853,717 | 52.7 |

| Yes | 130 | 334,642 | 110 | 277,279 | 82.9 | 98 | 244,551 | 73.1 | |

| Potential TBI | No | 701 | 1,767,487 | 474 | 1,127,035 | 63.8 | 353 | 793,874 | 44.9 |

| Yes | 2,311 | 5,882,984 | 1,712 | 4,276,544 | 72.7 | 1,384 | 3,304,394 | 56.2 | |

| Region | Midwest | 914 | 1,988,216 | 668 | 1,398,200 | 70.3 | 541 | 1,072,526 | 53.9 |

| South | 1,008 | 2,720,715 | 716 | 1,875,129 | 68.9 | 567 | 1,458,077 | 53.6 | |

| West | 720 | 1,841,674 | 528 | 1,317,647 | 71.5 | 425 | 1,005,487 | 54.6 | |

| Northeast | 370 | 1,099,866 | 274 | 812,603 | 73.9 | 204 | 562,178 | 51.1 | |

| Population Size | Under 50K | 1,852 | 4,612,312 | 1,340 | 3,235,453 | 70.1 | 1,073 | 2,492,963 | 54.1 |

| 50K-250K | 631 | 1,630,186 | 477 | 1,193,815 | 73.2 | 387 | 931,333 | 57.1 | |

| Over 250K | 529 | 1,407,973 | 369 | 974,312 | 69.2 | 277 | 673,971 | 47.9 | |

| Police Report | No | 1,336 | 3,271,726 | 932 | 2,191,525 | 67.0 | 768 | 1,709,629 | 52.3 |

| Yes | 1,626 | 4,258,017 | 1,229 | 3,151,614 | 74.0 | 949 | 2,343,983 | 55.0 |

| Reporting ≥1 emotional symptom | Reporting ≥1 physical symptom | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | CI low | CI high | Odds ratio | CI low | CI high |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| s1(age) | 1.024 | 1.010 | 1.038 | 1.043 | 1.029 | 1.056 |

| s2(age) | 0.979 | 0.949 | 1.010 | 0.951 | 0.925 | 0.977 |

| s1(year) | 0.859 | 0.387 | 1.906 | 1.653 | 0.795 | 3.437 |

| s2(year) | 1.127 | 0.653 | 1.944 | 0.725 | 0.439 | 1.197 |

| Any Injury (Yes v No) | 1.955 | 1.132 | 3.376 | 2.794 | 1.687 | 4.627 |

| Female (Yes v No) | 2.943 | 2.352 | 3.681 | 3.610 | 2.887 | 4.515 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native (Yes v No) | 2.162 | 0.857 | 5.458 | 2.748 | 1.303 | 5.798 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (Yes v No) | 1.620 | 0.680 | 3.858 | 1.986 | 0.913 | 4.319 |

| Black (Yes v No) | 1.054 | 0.784 | 1.415 | 0.786 | 0.607 | 1.017 |

| Hispanic (Yes v No) | 1.014 | 0.769 | 1.337 | 0.776 | 0.605 | 0.996 |

| Multiracial (Yes v No) | 1.182 | 0.745 | 1.874 | 0.998 | 0.666 | 1.497 |

| HS or Less (Yes v No) | 1.022 | 0.836 | 1.249 | 1.054 | 0.878 | 1.265 |

| Unconscious (Yes v No) | 1.495 | 1.196 | 1.869 | 1.503 | 1.221 | 1.849 |

| Population Size: 50k–250k | 1.200 | 0.932 | 1.545 | 1.254 | 0.997 | 1.577 |

| Population Size: ≥250k | 0.900 | 0.680 | 1.192 | 0.853 | 0.660 | 1.104 |

| Prepared Attack (Yes v No) | 1.448 | 1.187 | 1.768 | 1.121 | 0.934 | 1.346 |

| Region: Midwest | 0.890 | 0.637 | 1.244 | 1.252 | 0.929 | 1.688 |

| Region: South | 0.762 | 0.555 | 1.046 | 1.208 | 0.908 | 1.608 |

| Region: West | 0.953 | 0.671 | 1.355 | 1.316 | 0.966 | 1.793 |

| Outcome | Sex | Injury | Race | Predicted Probability (95% CI) |

| Physical symptom | Male | No Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.476 (0.275–0.677) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.399 (0.203–0.596) | |||

| Black | 0.213 (0.138–0.289) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.211 (0.135–0.288) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.255 (0.153–0.357) | |||

| White | 0.255 (0.179–0.332) | |||

| Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.709 (0.515–0.903) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.64 (0.423–0.858) | |||

| Black | 0.423 (0.265–0.581) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.42 (0.262–0.578) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.48 (0.306–0.653) | |||

| White | 0.48 (0.326–0.634) | |||

| Female | No Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.757 (0.607–0.907) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.695 (0.523–0.867) | |||

| Black | 0.484 (0.381–0.586) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.481 (0.375–0.586) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.541 (0.412–0.67) | |||

| White | 0.541 (0.449–0.634) | |||

| Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.894 (0.803–0.986) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.86 (0.745–0.976) | |||

| Black | 0.715 (0.584–0.846) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.713 (0.581–0.844) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.76 (0.631–0.888) | |||

| White | 0.76 (0.647–0.873) | |||

| Emotional symptom | Male | No Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.606 (0.367–0.844) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.537 (0.309–0.765) | |||

| Black | 0.432 (0.311–0.553) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.423 (0.303–0.543) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.46 (0.307–0.613) | |||

| White | 0.42 (0.312–0.527) | |||

| Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.748 (0.534–0.962) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.691 (0.465–0.917) | |||

| Black | 0.594 (0.42–0.769) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.585 (0.411–0.76) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.621 (0.434–0.808) | |||

| White | 0.582 (0.415–0.749) | |||

| Female | No Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.816 (0.664–0.969) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.769 (0.607–0.932) | |||

| Black | 0.686 (0.586–0.786) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.678 (0.576–0.78) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.71 (0.586–0.834) | |||

| White | 0.675 (0.583–0.767) | |||

| Injury | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.896 (0.788–0.999) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.866 (0.742–0.99) | |||

| Black | 0.809 (0.698–0.92) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.803 (0.69–0.916) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.826 (0.71–0.941) | |||

| White | 0.801 (0.691–0.911) |

| Outcome | Sex | Injury | Race | Predicted Probability (95% CI) |

| Physical symptom | Male | No Injury | White | 0.255 (0.179–0.332) |

| Hispanic | 0.211 (0.135–0.288) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.255 (0.153–0.357) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.399 (0.203–0.596) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.476 (0.275–0.677) | |||

| Black | 0.213 (0.138–0.289) | |||

| Injury | White | 0.48 (0.326–0.634) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.42 (0.262–0.578) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.48 (0.306–0.653) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.64 (0.423–0.858) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.709 (0.515–0.903) | |||

| Black | 0.423 (0.265–0.581) | |||

| Female | No Injury | White | 0.541 (0.449–0.634) | |

| Hispanic | 0.481 (0.375–0.586) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.541 (0.412–0.67) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.695 (0.523–0.867) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.757 (0.607–0.907) | |||

| Black | 0.484 (0.381–0.586) | |||

| Injury | White | 0.76 (0.647–0.873) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.713 (0.581–0.844) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.76 (0.631–0.888) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.86 (0.745–0.976) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.894 (0.803–0.986) | |||

| Black | 0.715 (0.584–0.846) | |||

| Emotional symptom | Male | No Injury | White | 0.42 (0.312–0.527) |

| Hispanic | 0.423 (0.303–0.543) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.46 (0.307–0.613) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.537 (0.309–0.765) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.606 (0.367–0.844) | |||

| Black | 0.432 (0.311–0.553) | |||

| Injury | White | 0.582 (0.415–0.749) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.585 (0.411–0.76) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.621 (0.434–0.808) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.691 (0.465–0.917) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.748 (0.534–0.962) | |||

| Black | 0.594 (0.42–0.769) | |||

| Female | No Injury | White | 0.675 (0.583–0.767) | |

| Hispanic | 0.678 (0.576–0.78) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.71 (0.586–0.834) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.769 (0.607–0.932) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.816 (0.664–0.969) | |||

| Black | 0.686 (0.586–0.786) | |||

| Injury | White | 0.801 (0.691–0.911) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.803 (0.69–0.916) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.826 (0.71–0.941) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.866 (0.742–0.99) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.896 (0.788–0.999) | |||

| Black | 0.809 (0.698–0.92) |

| Outcome | Sex | Probable TBI | Race | Predicted Probability (95% CI) |

| Emotional symptom | Female | Yes | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.928 (0.851–1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.906 (0.816–0.996) | |||

| Black | 0.863 (0.781–0.945) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.858 (0.774–0.942) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.876 (0.792–0.96) | |||

| White | 0.857 (0.776–0.937) | |||

| No | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.896 (0.788–0.999) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.866 (0.742–0.99) | |||

| Black | 0.809 (0.698–0.92) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.803 (0.69–0.916) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.826 (0.71–0.941) | |||

| White | 0.801 (0.691–0.911) | |||

| Male | Yes | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.815 (0.647–0.983) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.768 (0.582–0.955) | |||

| Black | 0.685 (0.534–0.836) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.677 (0.525–0.829) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.709 (0.55–0.868) | |||

| White | 0.674 (0.53–0.818) | |||

| No | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.748 (0.534–0.962) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.691 (0.465–0.917) | |||

| Black | 0.594 (0.42–0.769) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.585 (0.411–0.76) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.621 (0.434–0.808) | |||

| White | 0.582 (0.415–0.749) | |||

| Physical symptom | Female | Yes | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.927 (0.862–0.992) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.902 (0.818–0.986) | |||

| Black | 0.788 (0.685–0.891) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.786 (0.683–0.889) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.824 (0.726–0.923) | |||

| White | 0.825 (0.739–0.91) | |||

| No | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.894 (0.803–0.986) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.86 (0.745–0.976) | |||

| Black | 0.715 (0.584–0.846) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.713 (0.581–0.844) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.76 (0.631–0.888) | |||

| White | 0.76 (0.647–0.873) | |||

| Male | Yes | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.783 (0.625–0.941) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.725 (0.538–0.911) | |||

| Black | 0.52 (0.364–0.675) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.517 (0.362–0.672) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.577 (0.413–0.74) | |||

| White | 0.577 (0.433–0.721) | |||

| No | American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.709 (0.515–0.903) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.64 (0.423–0.858) | |||

| Black | 0.423 (0.265–0.581) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.42 (0.262–0.578) | |||

| Multiracial | 0.48 (0.306–0.653) | |||

| White | 0.48 (0.326–0.634) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).