1. Introduction

Human societies transitioned from foraging to settled agriculture, selectively cultivating crops to support growing populations. Today, global cropland spans over 1.5 billion hectares, intensifying pressure to meet escalating food demand [

1]. Climate change exacerbates these challenges through desertification, flooding, salinity, and heightened disease pressure, compelling reliance on synthetic fertilizers and agrochemicals to maintain yields [

2]. However, increasing awareness of environmental and health impacts, including soil degradation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss, has shifted focus toward regenerative practices [

3]. Agriculture now confronts a critical paradox: producing sufficient food for a projected global population of nearly 10 billion by 2050 while drastically reducing its ecological footprint [

1,

2,

3]. This urgency is amplified by climate-induced abiotic stresses [

2], and historical input-dependent farming models [

3], necessitating innovative tools like biostimulants to reconcile productivity with sustainability.

In response, the agricultural sector has embraced more sustainable paradigms, including integrated pest management (IPM), regenerative agricultural practices, and organic production, reflecting a shift in both practice and market demand [

4]. However, these systems often face a productivity gap compared to conventional agriculture and can struggle with reliable nutrient delivery and effectively manage pest suppression (insects, pathogens and weeds), particularly under stress conditions [

5]. This limitation has unveiled a critical need for novel innovations that can consistently enhance crop resilience and resource efficiency without relying solely on conventional chemical inputs.

Agricultural biologicals amendments, particularly biostimulants (both living microbial organisms and non-living), have emerged as a promising category of inputs to address this need. Biostimulants are defined as substances or microorganisms or their synthetic derivatives that stimulate natural processes to enhance nutrient uptake, efficiency, abiotic stress tolerance, and/or crop quality traits, regardless of their nutrient content [

6]. These biostimulants represent a paradigm shift in crop management [

6]. The biostimulants concept dates to ancient farmer practices and early scientific discoveries of plant-microbe symbiosis in the 19th century, which has evolved into a rapidly expanding industry today [

7]. This development is driven by consumer demand for sustainable food, stricter environmental regulations, new policies for clean air, water and environment particularly in the European Union, and the need for climate-resilient agriculture. The global bio stimulant market is now projected to reach USD 6-8 billion by 2030-2035, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10-13% [

8]. The biostimulants category encompasses a vast diversity of products, broadly classified as microbials to refer to being produced/processed from natural materials. The commonest examples include plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) which encompass the “living”, while the non-microbials includes seaweed extracts, humic substances, and protein hydrolysates [

9].

This very diversity has led to significant complexity and confusion regarding definitions, modes of action, and functional classifications, often blurring the lines with biofertilizers and biopesticides [

10,

11]. For growers, this confusion translates into a major practical barrier: the difficulty of selecting and using products effectively. A lack of understanding of specific modes of action makes product choice challenging [

10,

12]. For example, a symbiotic root microbial colonizer may need to be applied when there are a host plant and application to a non-host plant may result in relationship failure and therefore loss of function. This critically affects the efficacy of biostimulants, making it notoriously variable and highly dependent on a complex interplay of factors including environmental conditions, soil microbiota, crop species, application method and agronomic management [

13]. A product demonstrating significant effects in one trial condition may show no effect in another, leading to inconsistent field results and eroding farmer confidence [

9,

10]. The common referred to failure example of biostimulants in the North Great Plains (NGP) of the United States is the multi-state trial on commercially available products on yield advancement and nitrogen reduction in common row crops which showed no response in more than 70% of the trials [

14]. This variability suggests biostimulants are not simple "silver bullets" but tools whose success depends on a deep understanding of their interaction with the entire cropping system.

These practical challenges underscore critical knowledge gaps. There is a pressing need to move beyond isolated case studies and provide a synthesized, critical analysis of biostimulant performance across diverse environments. A comprehensive understanding of how their modes of action translate into efficacy under specific abiotic stresses, and how their activity is modulated by soil properties and amendments, is essential for guiding both research and farmer practical adoption. Therefore, this review aims to provide a systematic analysis of the biostimulants in Sustainable Agricultural Systems focusing on Performance, modes of action, efficacy under stress, and interactions with soil environments. Our specific objectives are to:

Systematically classify biostimulants based on their biological sources and primary functional mechanisms.

Critically assess their documented efficacy in mitigating major abiotic and biotic stresses and enhancing nutrient use efficiency.

Analyze the environmental, biological, and managerial factors that drive their variable performance in agronomic settings.

Evaluate the interactions between biostimulants and soil physicochemical properties and common agricultural amendments.

Synthesize both positive and negative research findings to provide a balanced evidence base.

Provide evidence-based recommendations for their practical integration into sustainable crop production systems and identify key future research priorities.

2. Classification and Composition of Biostimulants

2.1. A Framework for Categorization

The application of substances to enhance plant growth predates scientific understanding, with ancient agricultural practices utilizing seaweed and their extracts, plant extracts, animal and bird manures to improve soil fertility and crop vigor [

7]. Early scientific developments in biostimulants began to emerge in the late 19th century with the landmark discovery of nitrogen-fixing bacteria (

Rhizobium spp.) by Hellriegel and Wilfarth in 1886, which laid the groundwork for microbial inoculants [

6,

15,

16]. The mid-20th century saw systematic investigation of non-microbial sources, particularly seaweed extracts (

Ascophyllum nodosum), for their ability to promote growth and stress tolerance beyond mere nutrient provision [

16,

17]. The term "biostimulant" gained currency in the 1980s and 1990s, coinciding with the commercialization of plant-growth-promoting microorganisms (PGPMs). Subsequent decades expanded the category to include humic substances, amino acids, protein hydrolysates, and other novel compounds, driven by advances in extraction technologies and a growing understanding of plant-microbe interactions [

7,

9,

10].

The extraordinary diversity of biostimulants, ranging from live microbes to complex chemical mixtures necessitates a clear classification system to understand their function and application. The most fundamental classification divides them into two overarching categories based on the nature of their active ingredient: microbial and non-microbial [

6,

10,

18]. This dichotomy is crucial as it dictates the product's mode of action, stability, handling requirements, and interaction with the environment. For example, the living needs food (source of energy) when inactivated and a live host to colonize when applied to the environment.

Microbial biostimulants consist of beneficial microorganisms that actively colonize the rhizosphere or plant tissues to stimulate growth through a variety of biological processes. The microbials are typically standardized by colony or spore-forming unit counts (bacteria vs fungi) or filaments depending on the source and require specific formulation and handling to maintain viability [

19,

20]. Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria category includes bacteria such as

Bacillus,

Pseudomonas,

Azospirillum, and

Rhizobium. These have various modes of action including biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), solubilization of phosphorus and potassium, production of phytohormones like auxins, and induction of systemic resistance (ISR) against pathogens [

18,

21]. Another important group is beneficial fungi, which encompasses arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) such as

Glomus, and

Rhizophagus spp., that extend the root system, enhancing water and nutrient uptake, and fungal biocontrol agents like

Trichoderma spp. that antagonize pathogens through competition, mycoparasitism, and secretion of cell-wall-degrading enzymes [

22,

23].

Non-microbial biostimulants are the largest of these commercially available products and comprise non-living substances derived from organic or inorganic sources. Their efficacy is based on their chemical composition, and they are characterized by the concentration of active compounds e.g., 12% humic acid, and 15% amino acids, offering greater shelf stability but lacking the ability to reproduce or colonize [

24]. These include products like Humic Substances, which are derived from decomposed organic matter like peat, and compost. Humic and fulvic acids substances improve soil structure and cation exchange capacity (CEC), enhance root membrane permeability, and chelate nutrients, making them more available to plants [

25,

26].

Beyond humic substances, seaweed extracts represent a major category of non-microbial biostimulants. Sourced primarily from brown algae such as

Ascophyllum nodosum and

Ecklonia maxima, these complex extracts are valued for their rich composition of polysaccharides [

27] (e.g., alginates), betaines, and natural phytohormones including cytokinins and auxins. These components collectively enhance stress tolerance, improve nutrient efficiency, and increase crop yield [

27,

28]. Commercially available products in this category include Acadian Organic (Acadian Seaplants (Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada, B3B 1X8)), Kelpak® (Kelpak Products International - Capricorn Business Park, Cape Town, Western Cape, 7945, South Africa), and YieldOn® from Syngenta - Houston, TX 77070, USA).

Another significant category consists of protein hydrolysates and amino acids, which are derived from plant or animal by-products through enzymatic or chemical hydrolysis. These formulations provide a bioavailable source of organic nitrogen, function as natural chelating agents, and serve as precursors for stress-related metabolites and plant hormones [

29]. A representative commercial product is Terra-Sorb® (FMC Corporation). Inorganic compounds also constitute an important class of non-microbial biostimulants that are commonly utilized for stress remediation. Silicon-based products enhance plant structural integrity and abiotic stress tolerance, while phosphites induce defense pathways against oomycete pathogens such as

Phytophthora and

Pythium species [

30,

31]. Notable commercial examples include Nutri-Phite® (Nutri-Tech Solutions - Yandina, Queensland 4561, Australia) and Sil-Matrix® (Certis USA LLC - Columbia, Maryland 21046, U.S.A).

The category of botanicals and biopolymers encompasses a diverse range of plant-derived extracts and processed natural polymers. This includes extracts from species such as

Moringa and

Yucca, which are rich in antioxidants and saponins, and chitosan, a biopolymer derived from shellfish exoskeletons that elicits plant defense responses [

31,

32]. Commercially available products in this segment include Amplify™ (AgriGro, Doniphan, MO, USA) and ARMOUR-ZONE (Westbridge Agricultural Products, Chelsea, Vista, CA, USA).

Table 1.

Classification of common biostimulant categories, their sources, modes of action, and example products.

Table 1.

Classification of common biostimulant categories, their sources, modes of action, and example products.

| Category |

Primary Sources |

Typical Mode of Action (MOA) |

Example Products & Formulations |

| Microbial Biostimulants |

| PGPR |

Bacteria: Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Azospirillum, Rhizobium |

Nutrient solubilization, N-fixation, phytohormone production, Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) |

Utrisha™ N (Corteva; liquid), TerraMax (BASF; granular) |

| Beneficial Fungi |

Fungi: Mycorrhizae (AMF), Trichoderma |

Enhanced root surface area, nutrient/water uptake, pathogen antagonism |

Trianum™ (Koppert; powder), MycoApply® (granules) |

| Non-Microbial Biostimulants |

| Humic Substances |

Leonardite, peat, compost |

Improve soil CEC & structure, nutrient uptake, hormone-like activity |

Humifirst (liquid), Black Earth (granular) |

| Seaweed Extracts |

Brown algae: Ascophyllum nodosum |

Betaines, polysaccharides, and phytohormones enhance stress tolerance |

Acadian (liquid), Kelpak® (liquid) |

| Protein Hydrolysates |

Animal/plant by-products |

Source of bioavailable N, chelating agents, stress metabolite precursors |

Terra-Sorb® (FMC; liquid) |

| Inorganic Compounds |

Mineral deposits |

Structural integrity (Si), induced resistance (Phosphites) |

Sil-Matrix® (liquid), Nutri-Phite® (liquid) |

2.2. Functional Classification

Apart from their composition, biostimulants are most times categorized based on their main desired function, a trend that most times results in overlapping groups and produces a lot of regulatory as well as user confusion [

10]. This functional characterization is of three main groups: Biofertilizers which are products that have mainly the function of increasing availability of nutrients, solubilization, as well as plant absorption. Some examples are nitrogen-fixing inoculants such as

Rhizobium leguminosarum (e.g., TagTeam® COAT, provided by Novozymes BioAg Inc., Minnetonka, MN 55305, USA) and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria such as Bacillus megaterium (e.g., JumpStart®, produced by Novozymes BioAg Inc. as well as Corteva agro.

This encompasses another category of biopesticides that originate from products intended for pest, disease, or weed management through means of biological action. These include microbial agents such as

Bacillus thuringiensis in pest management [

33] (DiPel® DF, Valent BioSciences LLC, 870 Technology Way, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA) and fungal antagonists such as

Trichoderma harzianum for disease management (RootShield® Plus+, BioWorks Inc., Victor, NY 14564, USA and MycoUp™ from Corteva). Also included in the biopesticide category are seaweed products (e.g., Acadian® Organic, Acadian Seaplants Limited. 30 Brown Avenue, Dartmouth, NS B3B 1X8, Canada) and humic products (e.g., HumiFirst, HumiPlant, Unit E1, Burlington, ON L7L 5H9, Canada) [

6].

2.3. Formulation Technologies: (Active in Nature Versus Inactive)

Under the technical approach employed in formulation products are categorized as live and non-living microbials. Live microbial products, for example, must -in some cases- be fermented and stabilized through encapsulation methods specifically to protect their viability. Liveliness ensures dynamic interactions that can potentially exist over long periods of time when stored properly [

10]. Non-microbial products, on the other hand, take advantage of other extraction and purification methods (e.g. alkaline hydrolysis) to produce bioactive compounds, which are stable and enjoyable use [

10], but typically function through direct stimulation of chemicals [

19]. Recently there has been a movement towards dividing this exceptional category of products into two factions, with new inventions such as microbial engineering and nanotechnology bridging a gap and fostering higher efficacy and consistency within both categories of products [

9,

10]. Still, even with these unique aspects, identification persists in being a major issue towards incorporating biostimulants at the grower’s level, partially because of a lack of awareness [

33], who often improperly identify biostimulants as nothing more than a modified fertilizer or pesticide supplemented with natural materials.

3. Modes of Action: The Way Biostimulants Work

Biostimulants enhance plant physiological processes without acting as primary nutrients or pesticides like how synthetic chemicals do. Their primary modes of action include metabolic priming and molecular signaling, which collectively improve growth, stress tolerance, and yield.

The principal mechanism is the modulation of phytohormones. Microbial biostimulants, such as PGPR and beneficial fungi, synthesize and release phytohormones including auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins [

21,

28,

34,

35]. These regulate cell division, elongation, and differentiation, thereby improving root architecture and shoot development, which increases plants natural defense against pest and stress [

6,

13]. Non-microbial biostimulants (e.g., seaweed extracts) similarly contain hormone-like compounds that influence plant development.

Biostimulants also enhance enzymatic activity in nitrogen assimilation and carbon metabolism, improving nutrient use efficiency and biomass accumulation. Under abiotic stress, they induce osmotic adjustment through the accumulation of osmolytes (e.g., proline, glycine betaine), helping maintain cellular turgor [

36,

37]. Additionally, they mitigate oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, CAT, POD) and stress-responsive genes encoding protective proteins (e.g., HSPs, LEAs).

Against biotic stress, biostimulants induce systemic resistance. Beneficial microbes such as PGPR and

Trichoderma spp. elicit jasmonic acid/ethylene-dependent induced systemic resistance (ISR) through molecular signaling. This have been documented in cucumber [

38],

Arabidopsis thaliana [

39], and other plants species [

40]. Other compounds, including chitosan and seaweed extracts, stimulate salicylic acid-mediated systemic acquired resistance (SAR). Microbial agents also suppress pathogens via competitive exclusion, antibiosis, and the production of siderophores, antibiotics, and lytic enzymes [

16,

22,

41,

42,

43]. Furthermore, biostimulants like humic substances enhance soil structure by promoting aggregation and porosity, thereby supporting root growth and nutrient diffusion [

44]. The good example is beneficial microbes such as PGPR and fungi like

Trichoderma which colonize roots and trigger jasmonic acid/ethylene-dependent induced systemic resistance (ISR), priming the plant for accelerated defense response upon pathogen attack [

40,

43].

Alternatively, compounds like chitosan and seaweed extracts stimulate salicylic acid-mediated systemic acquired resistance (SAR), particularly effective against biotrophic pathogens [

45]. Additionally, microbial biostimulants suppress diseases via competitive exclusion and antibiosis through the release of siderophores, antibiotics, and lytic enzymes [

16,

22]. The core function of biostimulants lies in improving nutrient use efficiency. Microbial strains solubilize insoluble nutrients, while mycorrhizal fungi extend root reach via hyphal networks [

46,

47]. In legumes, rhizobia symbiosis enables biological nitrogen fixation, providing sustainable nitrogen nutrition [

16,

48]. Concurrently, biostimulants like humic substances and microbial exudates improve soil structure by enhancing aggregation and porosity, facilitating better root growth and nutrient diffusion [

25].

Table 2.

Key Modes of Action for Major Biostimulant Categories.

Table 2.

Key Modes of Action for Major Biostimulant Categories.

| Biostimulant Category |

Primary Modes of Action (MOA) |

Key Bioactive Compounds/Mechanism |

PGPR (e.g., Bacillus

,Pseudomonas)

|

N-fixation, P-solubilization, Phytohormone production (IAA), ISR, Antibiosis |

IAA, Siderophores, ACC deaminase, Antibiotics, Exopolysaccharides |

|

Beneficial Fungi (AMF,Trichoderma)

|

Enhanced nutrient/water uptake, Pathogen antagonism, ISR |

Extensive hyphal network, Mycoparasitism, Chitinase enzymes |

| Seaweed Extracts |

Osmotic adjustment, Antioxidant defense, Phytohormone-like activity |

Betaines, Polysaccharides (alginates, laminarin), Cytokinins, Auxins |

| Humic Substances |

Improved soil CEC, Root membrane permeability, Nutrient chelation |

Humic acids, Fulvic acids, Polyphenols |

| Protein Hydrolysates/Amino Acids |

Chelation, Osmoregulation, Metabolic precursors |

Free L-amino acids, Peptides, Organic Nitrogen |

| Chitosan |

Elicitation of plant defenses (SAR), Antimicrobial activity |

Chitin derivatives, Oligosaccharides |

These products do not provide a single silver bullet but rather modulate the plant's own systems for growth, stress response, and nutrient acquisition. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for aligning the correct biostimulant type with specific agronomic challenges, which is the focus of the following sections.

4. Efficacy Under Specific Abiotic Stresses

Biostimulants enhance plant resilience to abiotic stresses by targeting specific physiological response pathways which are affected by the environment and thus, a single biostimulant can produce both positive and negative response under diverse conditions [

2,

12]. Under drought stress, microbial plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) such as

Azospirillum brasilense and

Bacillus subtilis improve soil moisture retention and root exploration through exopolysaccharide production, while non-microbial biostimulants like seaweed extracts and humic acids enhance osmoprotectant synthesis (proline, glycine betaine) and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT) to maintain cellular integrity [

37,

49,

50,

51]. Some studies have documented both negative and positive yield increases up to 68% under moderate drought conditions [

19,

52].

For salinity stress, halotolerant PGPR (e.g.,

Bacillus pumilus) regulate ion homeostasis by enhancing K⁺/Na⁺ ratios and reducing stress ethylene via ACC deaminase, while arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) improve phosphorus and water acquisition, with complementary foliar applications of amino acids and seaweed extracts providing substrates for compatible solutes and oxidative defense [

53,

54,

55]. Under temperature extremes, biostimulants such as seaweed extracts, protein hydrolysates, and amino acids stabilize membranes and proteins through heat-shock protein induction and cryoprotectant accumulation [

56,

57,

58].

Waterlogging stress is mitigated through bacterial promotion of aerenchyma formation for oxygen transport and improved nitrogen metabolism [

59,

60]. This is achieved through soil structure building and enhancing plant antioxidant defense by AMF [

61,

62,

63]. Others from bacteria produce hormones and scavenge harmful oxygen species, increase osmoregulatory compounds and improve nutrient availability which helps the plant to survive water stress. Mechanisms include ACC deaminase production, which lowers stress-induced ethylene, and the synthesis of osmoprotectants and antioxidants [

63,

64].

Table 3.

Efficacy of Biostimulants in Mitigating Key Abiotic Stresses.

Table 3.

Efficacy of Biostimulants in Mitigating Key Abiotic Stresses.

| Abiotic Stress |

Key Physiological Challenge |

Effective Biostimulant Types |

Primary Mechanism of Mitigation |

Reference |

| Drought |

Osmotic stress, Oxidative damage |

PGPR, Seaweed extracts, Humic acids |

Osmolyte accumulation, Antioxidant induction, Improved root architecture |

[37] |

| Salinity |

Iron toxicity, Osmotic stress |

Halotolerant PGPR, AMF, Amino acids |

Ion homeostasis (↑K⁺/Na⁺), Osmotic adjustment, Antioxidant defense |

[51] |

| Heat Stress |

Protein denaturation, Membrane instability |

Trichoderma spp., PGPR, Seaweed extracts |

Heat-shock protein (HSP) induction, Membrane stabilization |

[48] |

| Chilling Stress |

Membrane rigidification, ROS generation |

Microbial consortia, Seaweed extracts |

Cryoprotectant synthesis, Antioxidant defense |

[65] |

| Flooding |

Hypoxia, Reduced nutrient uptake |

Azospirillum, Pseudomonas spp. |

Aerenchyma formation, Anaerobic metabolism support |

[50] |

5. Efficacy Against Biotic and Physiological Stresses

5.1. Suppression of Pathogens and Nematodes

Biostimulants combat diseases primarily through induced systemic resistance (ISR) and competitive microbial exclusion. Beneficial rhizobacteria (PGPR) and fungi (e.g.,

Trichoderma, mycorrhizae) colonize root zones to prime jasmonic acid/ethylene defense pathways, enabling accelerated response to pathogen attack [

43]. Additional suppression mechanisms include antibiotic production, siderophore-mediated iron competition, and direct mycoparasitism [

22]. Practical applications demonstrate

Trichoderma harzianum effectively reducing soil-borne diseases like damping-off (

Pythium spp.) and wilt (

Fusarium spp.), while

Bacillus and

Pseudomonas strains counter bacterial and fungal pathogens through multiple mechanisms [

66,

67,

68]. For instance,

Bacillus subtilis inoculation reduces

Fusarium oxysporum impact in tomatoes [

69], while

Pseudomonas putida suppresses

Fusarium oxysporum through siderophore production and enhanced photosynthesis [

70,

71]. Notably,

Bacillus aryabhattai strain SRB02 controls tomato Fusarium wilt by inhibiting fungal growth while modulating host defense through enhanced salicylic acid and amino acid accumulation [

52]

5.3. Alleviation of Physiological Stresses

Biostimulants address internal imbalances through multiple mechanisms: humic substances celebrating micronutrients (Fe, Zn) to improve availability [

25]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhances phosphorus acquisition via extended hyphal networks [

47]; while amino acids and seaweed extracts reduce transplant shock through organic nitrogen supply and root regeneration stimulation [

72]; and reproductive stress is mitigated via improved pollen viability and fruit set [

48]. Additionally, quality parameters including sugar content (brix), anthocyanin levels, and shelf life are significantly enhanced through targeted applications [

28]. In addition, post-injury applications of amino acids and seaweed extracts accelerate tissue repair by supplying substrates for protein synthesis and cell wall regeneration while mitigating oxidative damage [

73].

Table 4.

Efficacy of Biostimulants in Mitigating Biotic and Physiological Stresses.

Table 4.

Efficacy of Biostimulants in Mitigating Biotic and Physiological Stresses.

| Stress Category |

Specific

Challenge

|

Effective Biostimulant Types |

Primary Mechanism of Action |

Reference |

| Biotic Stress |

Soil-borne pathogens (e.g., Fusarium, Pythium) |

Trichoderma spp., PGPR (Bacillus, Pseudomonas) |

Mycoparasitism, Competition, Antibiosis, Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) |

[59] |

| |

Insect pests (e.g., aphids, mites) |

Chitosan, Phenolic-rich plant extracts |

Cell wall signification, Induction of defensive secondary metabolites |

[69,70] |

| Physiological Stress |

Nutrient deficiency (e.g., P, Fe, Zn) |

AMF, Humic substances, PSB |

Nutrient solubilization, Chelation, Enhanced root surface area |

[74,75] |

| |

Transplant shock |

Amino acids, Seaweed extracts |

Supply of organic N, Stimulation of root regeneration |

[72] |

| |

Poor fruit set / flowering |

Amino acids, Microbial consortia |

Improved pollen viability, Hormonal modulation |

[48] |

| |

Physical injury (hail, wind) |

Amino acids, Seaweed extracts |

Callus formation, Energy metabolism recovery |

[8] |

6. Performance Variability and Influencing Factors

The most consistent finding in biostimulant research is the inherent variability in product efficacy, where significant improvements in stress tolerance or yield in some contexts contrast with null or even negative results in others [

76,

77]. This inconsistency stems not from product deficiency but from the complex interplay of biological, environmental, and management factors that modulate biostimulant performance. Understanding these influences is crucial for interpreting experimental results, setting realistic agricultural expectations, and enhancing product reliability [

12,

56].

6.1. Fundamental Principles Governing Variability

Two core principles explain much of the observed performance variation: 1). The limiting factor principle posits that biostimulants demonstrate maximal efficacy when addressing specific physiological constraints. For instance, phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms (e.g.,

Pseudomonas spp.) show significant growth promotion in low-phosphorus soils but provide negligible benefits in phosphorus-replete conditions [

78]. Similarly, osmoprotectant-rich seaweed extracts (e.g., from

Ascophyllum nodosum) substantially improve drought tolerance in water-limited environments but show minimal effects under optimal irrigation [

79,

80]. 2). The biological competition axiom states that successful establishment of microbial biostimulants depends on their ability to compete with resident soil communities [

81,

82]. Inoculants often fail when outcompeted by native microbiota, inhibited by chemical residues from previous applications, or introduced to soils lacking sufficient organic matter to support colonization and growth, or introduced in environment with chemical inhibitors and lacking synagy [

81,

82].

6.2. Environmental and Edaphic Determinants

Field environments act as stringent filters on biostimulant performance through several mechanisms: Soil physicochemical properties significantly influence efficacy, with pH critically affecting microbial survival and bioactive compound stability (most beneficial bacteria thrive at pH 6.0-7.5) [

83,

84]. While soil texture determines product selection, sandy soils with low water-holding capacity respond well to moisture-retaining products like humic substances, whereas clay soils require oxygen-tolerant formulations, and amendment that improve aeration [

85,

86]. Additionally, the soil is composed of billions of native bacteria and fungi, which all determines whether introduced strains face synergy or competition, with established communities often exhibiting priority effects that limit colonization by new inoculants [

87]. Notably, degraded soils with low microbial diversity typically show stronger responses to inoculation than biologically diverse soils, the same way we see higher plant response to fertilizers under low fertility soils [

88,

89], as documented by Dadzie, et al. [

90] observed greater colonization by native micro-organisms in degraded soils. Even when other factors guide the criteria for microbial specie selection, the previous management history creates legacy effects that modulate efficacy, where previous fungicide applications can suppress fungal biostimulants (e.g.,

Trichoderma spp.), and high nitrogen fertilization reduces plant dependence on symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria [

89].

6.3. Climatic and Management Influences

Climatic factors dramatically affect biostimulant function: temperature regulates microbial metabolic rates (e.g.,

Azospirillum brasilense thrives in warm soils but performs poorly in cool conditions) and can denature heat-sensitive compounds in non-microbial formulations. For example, [

91] observed a reduction in growth with temperature in

Azospirillum brasilense C16 spp isolated from Guinea grass. Most of the soil micro-organisms need moisture to carry out their respiration and move in the soil. Moisture availability controls microbial mobility and nutrient diffusion; solar radiation degrades light-sensitive components in foliar applications, making early morning or evening application critical for efficacy [

92,

93,

94]. In addition to the soil environment, management practices often determine practical success: microbial product viability depends on maintained cold chains and proper storage conditions throughout the distribution network [

95], tank-mixing with incompatible chemicals e.g., copper-based fungicides with bacterial inoculants, or using poor quality water high chlorine, and extreme pH can inactivate products [

96,

97,

98]. Application timing must align with both crop growth stages and stress anticipation to achieve desired effects, as applying drought-mitigating products after severe stress establishment often proves ineffective. Previous rotation management including tillage, crop species, and residue (microbial food), influences the soil food web, which also influences the colonizing power of a new microbial inoculant [

99,

100]. This comprehensive framework explains why biostimulant performance is inherently context-dependent and underscores the importance of matching products to specific environmental conditions, soil properties, and management practices to achieve consistent results.

7. The Greenhouse vs. Field Efficacy Disparity

A critical analysis of biostimulant literature reveals a significant disconnect between results from controlled environments and working farms. While greenhouse studies dominate the published evidence base, their optimized conditions often fail to predict performance in the complex, dynamic realities of open-field agriculture. This "translation gap" profoundly impacts efficacy interpretation, research priorities, and farmer expectations.

7.1. Limitations of Controlled Environment Research

Greenhouse studies provide essential advantages for early-stage research: precise environmental control, high replication capacity, facilitated sampling, and accelerated results. These features make them indispensable for proof-of-concept work and mechanistic studies. However, these very advantages create inherent limitations for real-world prediction [

101]. The absence of complex stress interactions, where field crops face multiple simultaneous stresses (heat, water deficit, pest pressure), limits translational validity [

102]. The confined root environment of containers creates artificial rhizosphere conditions that intensify root exudate concentrations and distort nutrient dynamics, potentially exaggerating treatment effects [

103,

104]. Furthermore, greenhouse conditions buffer environmental extremes (UV radiation, wind, hail) that many biostimulants are designed to mitigate, while sterile or simplified potting media eliminate microbial competition, allowing unrealistically successful colonization of introduced inoculants [

101].

The greenhouse studies typically report strong, statistically significant improvements in biomass, nutrient uptake, and stress marker reduction due to biostimulants. But when these treatments are taken to the field conditions, they show modest, variable, or non-significant effects, and show strong season- and location-dependence [

101]. This discrepancy reflects how controlled environments optimize conditions for biostimulant expression, while field conditions with heterogeneous soils, unpredictable weather, and competitive biological communities create a stringent performance filter [

101].

The overreliance on greenhouse data results in failed translation of promising results and farmer skepticism [

105] creating unrealistic expectations and inconsistent outcomes, which all hinder adoption and recommendation confidence [

101]. Addressing this disparity requires a strategic approach: prioritizing multi-year, multi-location field trials that expose products to authentic stresses [

106], clearly contextualizing greenhouse findings with their limitations; and demanding local field validation data from manufacturers [

106,

107,

108]. While greenhouse research remains valuable for discovery, the future of biostimulants depends on bridging this gap through rigorous field validation.

8. Crop-Specific Responses to Biostimulants

The notion of a universal biostimulant is scientifically unsound given the profound physiological diversity among plant species and even varieties. Crops differ significantly in root architecture, nutrient demands, and stress tolerance mechanisms, making product efficacy highly crop specific [

109]. A biostimulant that enhances yield in one crop may show negligible or even negative effects in another, necessitating a precision-based approach rather than generalized applications of biostimulants [

110].

Cereals respond best to biostimulants targeting early nutrient acquisition and root development. Microbial inoculants, particularly PGPR like

Azospirillum and

Azotobacter, demonstrate consistent benefits through biological nitrogen fixation, auxin production, and phosphate solubilization, resulting in 5, 15% yield gains under field conditions [

110,

111,

112]. Cyanobacteria show special efficacy in flooded rice systems [

113,

114]. Optimal application involves seed treatment or in-furrow placement for microbial products, with foliar applications of seaweed extracts or humic substances timed to critical growth stages [

60]. Responses are often limited in high-fertility soils or when chemical seed treatments compromise microbial viability [

97].

Quality-driven horticultural production benefits particularly from fungal biostimulants.

Trichoderma species enhance root development and suppress soil-borne pathogens [

38,

59,

68], while AMF improves phosphorus uptake in nutrient-intensive crops like tomatoes and peppers [

75]. Non-microbial options including amino acid formulations and seaweed extracts reduce transplant shock and improve fruit quality parameters [

27,

28,

72,

73]. Application methods must align with objectives: soil incorporation for fungal benefits versus foliar sprays for quality enhancement [

76,

115]. Over-application of amino acids may stimulate excessive vegetative growth, and fungicide incompatibility can limit fungal biostimulant efficacy. Long-cycle crops (perennial crops), benefit from biostimulants that enhance long-term soil health and stress resilience. Humic substances improve soil structure and nutrient retention, while AMF established at planting provides lasting water and nutrient uptake benefits [

26]. Seaweed extracts mitigate intermittent stress events and improve harvest quality [

27,

28,

73]. Broadcast granular applications suit long-term soil improvement, while foliar sprays address anticipated stress events.

Table 5.

Crop-Specific Biostimulant Recommendations.

Table 5.

Crop-Specific Biostimulant Recommendations.

| Crop Type |

Key Challenges |

Recommended Types |

Application Method |

| Cereals |

Early establishment, nutrient efficiency |

PGPR, Humic acids |

Seed treatment, in-furrow |

| Legumes |

Biological nitrogen fixation |

Specific rhizobia |

Seed inoculation |

| Vegetables |

Soil diseases, transplant shock, quality |

Trichoderma, AMF, Seaweed extracts |

Soil incorporation, foliar |

| Plantations |

Long-term soil health, periodic stress |

Humic substances, AMF, Seaweed extracts |

Broadcast granules, foliar |

9. Biostimulants Interactions with Soil Amendments

Biostimulants are rarely applied in isolation but are integrated into agricultural systems employing various soil amendments to enhance fertility and soil health. These amendments ranging from organic materials like manures, and composts to inorganic inputs like lime create complex soil environments that significantly influence biostimulant performance, particularly for microbial products [

116,

117]. The interactions can be synergistic (amplifying benefits), additive (cumulative effects), or antagonistic (inhibitory), making understanding these dynamics crucial for optimizing biostimulant efficacy in both organic and conventional systems [

118,

119].

Soil amendments significantly influence biostimulant efficacy by modifying the soil environment in which they function. Organic amendments can have contrasting effects: well-composted organic matter provides stable habitat and resources that enhance microbial biostimulant activity, while fresh manure may introduce toxic ammonia levels and competitive microbiota that inhibit inoculated strains [

120,

121]. Biochar improves soil habitat and moisture retention but may absorb organic biostimulant compounds, while wood chips immobilize nitrogen during decomposition, limiting nutrient availability for both plants and microbes [

122]. Inorganic amendments similarly create variable conditions, lime and gypsum adjust pH to ranges that may favor or inhibit specific microbial communities, while sand improves drainage but offers minimal biological interaction [

123]. Thus, amendment selection and timing directly determine whether biostimulants encounter synergistic, neutral, or antagonistic conditions for their establishment and function.

Compost provides carbon sources that fuel microbial biostimulant activity [

117]; biochar's porous structure offers protective habitats for microbes [

118,

119]; well-composted matter buffers pH and adsorbs toxins

Antagonistic: High C: N amendments starve nitrogen-dependent microbes; biochar may adsorb organic biostimulant compounds [

118,

119]; chemical fertilizers can suppress mycorrhizal associations.

Table 8.

Amendment-Biostimulant Interactions.

Table 8.

Amendment-Biostimulant Interactions.

| Amendment |

Primary Effect |

Microbial Biostimulants |

Non-Microbial Biostimulants |

| Composted Manure |

Adds OM & nutrients |

Synergistic: food & habitat |

Additive/Synergistic |

| Fresh Manure |

High soluble N |

Antagonistic: toxicity |

Variable: salt degradation |

| Biochar |

Increases CEC, porosity |

Synergistic: habitat (adsorption risk) |

Antagonistic: adsorption |

| Wood Chips/Mulch |

N immobilization |

Antagonistic: N starvation |

Antagonistic: poor growth |

| Lime |

Raises pH |

Variable: pH-dependent |

Variable: alters solubility |

Successful integration requires: (1) preliminary soil testing to understand conditions; (2) prioritizing stabilized amendments over fresh; (3) strategic timing to avoid antagonisms; (4) matching amendment-biostimulant combinations to objectives; and (5) continuous monitoring and adaptation based on crop responses.

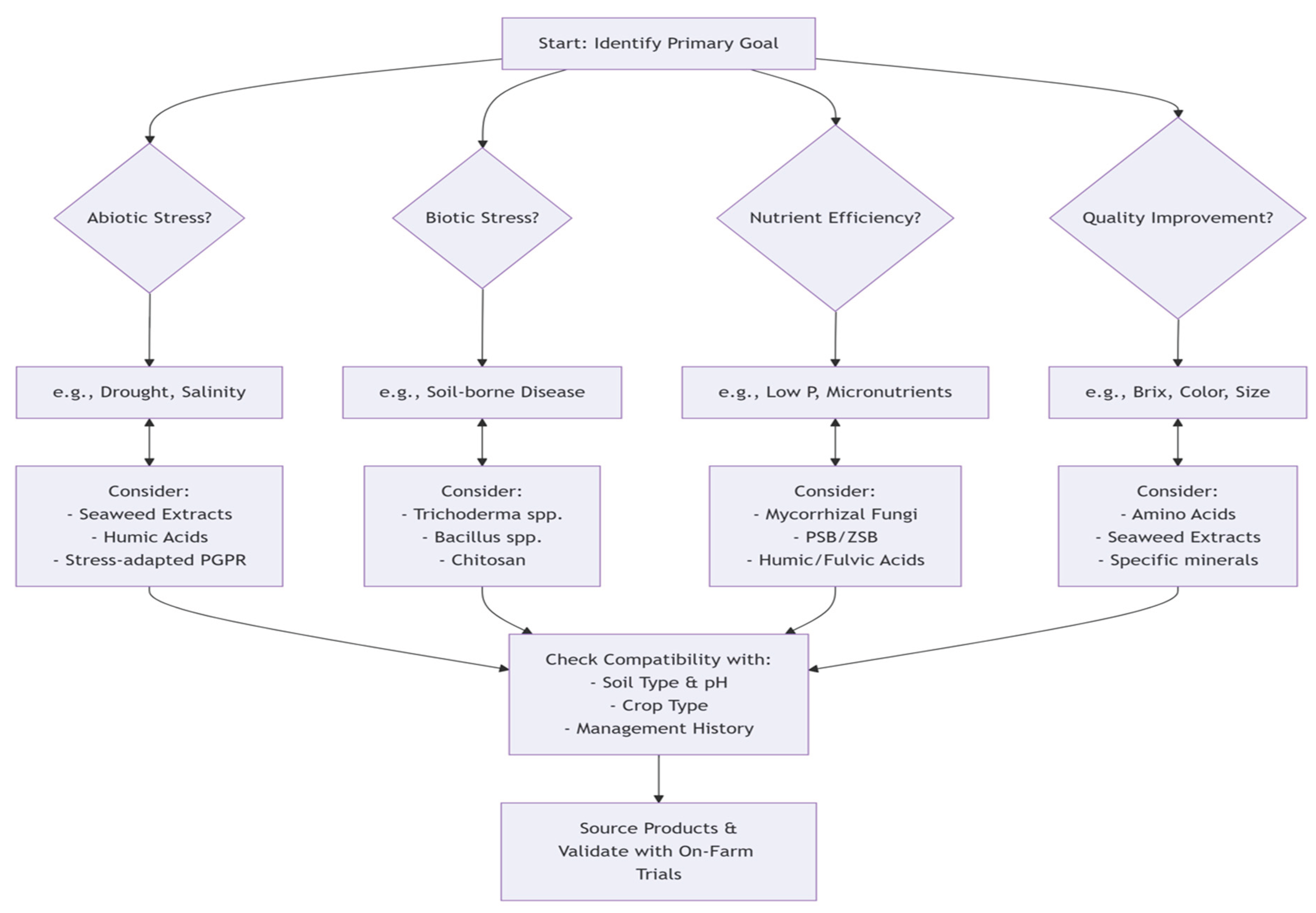

10. Observations and Recommendations

The comprehensive analysis confirms that biostimulant efficacy is inherently context-dependent, reflecting the complex interplay of biological, environmental, and management factors rather than product inconsistency. Four core principles explain performance variability: The observed variability in biostimulant performance can be understood through four foundational principles: the Limiting Factor Principle, where efficacy peaks when addressing specific constraints such as phosphate-solubilizing microbes in low-phosphorus soils; the Biological Competition Axiom, which states that microbial success depends on establishment within competitive soil ecosystems; the Stress Gradient Hypothesis, indicating that benefits are greatest under sub-optimal conditions compared to high-input systems; and the Formulation and Viability Imperative, where supply chain issues like improper storage and handling are responsible for many microbial product failures. These principles collectively underscore the context-dependent nature of biostimulant efficacy, emphasizing that success is determined by the alignment of product function with specific agricultural constraints and conditions. Effective use requires: (1) diagnosing primary constraints through soil testing; (2) integrating biostimulants into holistic management; (3) demanding local field validation data; (4) conducting on-farm trials; (5) proper handling of microbial products; (6) following a decision framework assessing soil health, stresses, and input history. Producers should: (1) provide transparent multi-location field data; (2) invest in advanced formulation technologies; (3) adopt targeted, evidence-based marketing; (4) educate distribution chains on proper handling.

Future work should: (1) prioritize field-based greenhouse studies; (2) elucidate mechanisms using omics tools; (3) develop crop- and amendment-specific protocols; (4) create predictive soil health tools; (5) establish industry-wide standards.

Figure 1.

A Framework for Biostimulant Recommendations.

Figure 1.

A Framework for Biostimulant Recommendations.

11. Conclusions

This review has addressed the growing imperative to enhance agricultural sustainability and productivity amidst climate change and environmental degradation. To this end, we have synthesized the current scientific understanding of agricultural biostimulants, examining their classification, modes of action, and efficacy against abiotic and biotic stresses. Our analysis confirms that biostimulants are sophisticated tools capable of modulating plant physiology to improve nutrient use efficiency, stress tolerance, and crop quality.

A central finding of this work is the profoundly context-dependent nature of biostimulant efficacy. Performance is not a function of product quality alone but is governed by a complex hierarchy of factors, including soil properties, native microbiota, climate conditions, crop species, and management practices. The significant disparity between highly controlled greenhouse studies and variable field results underscores the critical limitation of extrapolating data without accounting for real-world agroecosystem complexity. Furthermore, interactions with soil amendments can be either synergistic or antagonistic, necessitating an integrated systems approach rather than treating biostimulants as standalone solutions.

The primary take-home message is that biostimulants are not universal "silver bullets." Their successful implementation requires a precision-based approach, where product selection and application are carefully matched to specific environmental constraints and agronomic challenges. To bridge the gap between their significant potential and on-farm reliability, future research must prioritize multi-year, multi-location field trials to generate robust, validated efficacy data. Mechanistic studies using omics tools are needed to elucidate interactions with soil microbiomes under varying conditions. Furthermore, the development of crop- and amendment-specific protocols, predictive soil health tools, and industry-wide standards is essential.

Ultimately, unlocking the full promise of biostimulants for sustainable intensification demands a concerted effort across the sector: rigorous and transparent science, targeted education for growers and agronomists, and evolved regulatory frameworks that categorize products based on biological function. When applied judiciously within integrated management systems, biostimulants can be powerful components in developing more resilient and productive agricultural systems for future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Unius Arinaitwe, and Abraham Hangamaisho.; methodology, Unius Arinaitwe.; software, Unius Arinaitwe.; validation, Unius Arinaitwe., Abraham Hangamaisho.; formal analysis, Unius Arinaitwe and Abraham Hangamaisho.; investigation, Unius Arinaitwe.; resources, Unius Arinaitwe.; data curation; Unius Arinaitwe and Abraham Hangamaisho.; writing original draft preparation, Unius Arinaitwe.; writing review and editing, Unius arinaitwe and Abraham Hangamaisho.; supervision, Unius Arinaitwe.; project administration, Unius Arinaitwe.; funding acquisition, n/a.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data for this article is contained in it. For additional information, contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) took full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC |

1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate |

| AMF |

Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi |

| BNF |

Biological Nitrogen Fixation |

| CEC |

Cation Exchange Capacity |

| CAGR |

Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| Fe |

Iron |

| IPM |

Integrated Pest Management |

| ISR |

Induced Systemic Resistance |

| NGP |

North Great Plains |

| NUE |

Nutrient Use Efficiency |

| PGPR |

Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria |

| PGPM |

Plant-Growth-Promoting Microorganisms |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SAR |

Systemic Acquired Resistance |

| PGBF |

Plant growth Promoting Fungi |

References

- U. Nations, "United Nations Population Prospects 2024," United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf, 2024.

- S. I. Zandalinas, F. B. Fritschi, and R. Mittler, "Global warming, climate change, and environmental pollution: recipe for a multifactorial stress combination disaster," Trends in Plant Science, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 588-599, 2021.

- T. Gomiero, "Food quality assessment in organic vs. conventional agricultural produce: Findings and issues," Applied Soil Ecology, vol. 123, pp. 714-728, 2018.

- J. P. Reganold and J. M. Wachter, "Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century," Nature plants, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1-8, 2016.

- V. Seufert, N. Ramankutty, and J. A. Foley, "Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture," Nature, vol. 485, no. 7397, pp. 229-232, 2012.

- P. Du Jardin, "Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation," Scientia horticulturae, vol. 196, pp. 3-14, 2015.

- O. I. Yakhin, A. A. Lubyanov, I. A. Yakhin, and P. H. Brown, "Biostimulants in plant science: a global perspective," Frontiers in plant science, vol. 7, p. 2049, 2017.

- S. Gupta, P. Bhattacharyya, M. G. Kulkarni, and K. Doležal, "Growth regulators and biostimulants: upcoming opportunities," vol. 14, ed: Frontiers Media SA, 2023, p. 1209499.

- C. Sible and F. Below, "Role of Biologicals in Enhancing Nutrient Efficiency in Corn and Soybean," Crops & Soils, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 13-19, 2023.

- C. N. Sible, J. R. Seebauer, and F. E. Below, "Biostimulant or biological? The complexity of defining, categorizing, and regulating microbial inoculants," Agricultural & Environmental Letters, vol. 10, no. 2, p. e70027, 2025.

- R. Oliver, L. N. Jørgensen, T. M. Heick, G. M. Kemmitt, R. Bryson, and H. Brix, Instant Insights: Fungicide resistance in cereals. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2024.

- M. J. Van Oosten, O. Pepe, S. De Pascale, S. Silletti, and A. Maggio, "The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants," Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 5, 2017.

- Y. Rouphael and G. Colla, "Biostimulants in agriculture," vol. 11, ed: Frontiers Media SA, 2020, p. 40.

- D. Franzen et al., "Performance of selected commercially available asymbiotic N-fixing products in the north central region," North Dakota State Extension, vol. 4, 2023.

- J. Raymond, J. L. Siefert, C. R. Staples, and R. E. Blankenship, "The natural history of nitrogen fixation," Molecular biology and evolution, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 541-554, 2004.

- H. Hellriegel and H. Wilfarth, "Untersuchungen über die Stickstoffnahrung der Gramineen und Leguminosen," 1888.

- G. Blunden, "The effects of aqueous seaweed extract as a fertilizer additive," in Proc. Int. Seaweed Symp., 1972, vol. 7, pp. 584-589.

- P. Calvo, L. Nelson, and J. W. Kloepper, "Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants," Plant and soil, vol. 383, no. 1, pp. 3-41, 2014.

- M. Kumari, P. Swarupa, K. K. Kesari, and A. Kumar, "Microbial inoculants as plant biostimulants: A review on risk status," Life, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 12, 2022.

- J. Černohlávková, J. Jarkovský, M. Nešporová, and J. Hofman, "Variability of soil microbial properties: Effects of sampling, handling and storage," Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, vol. 72, no. 8, pp. 2102-2108, 2009.

- B. Lugtenberg and F. Kamilova, "Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria," Annual review of microbiology, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 541-556, 2009.

- G. E. Harman, C. R. Howell, A. Viterbo, I. Chet, and M. Lorito, "Trichoderma species—opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts," Nature reviews microbiology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 43-56, 2004.

- A. Wahab et al., "Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses," Plants, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 3102, 2023.

- M. Ciriello, E. Campana, G. Colla, and Y. Rouphael, "An Appraisal of Nonmicrobial Biostimulants’ Impact on the Productivity and Mineral Content of Wild Rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC.) Cultivated under Organic Conditions," Plants, vol. 13, no. 10, p. 1326, 2024.

- L. P. Canellas and F. L. Olivares, "Physiological responses to humic substances as plant growth promoter," Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 3, 2014.

- C. Kaya and F. Ugurlar, "Non-microbial Biostimulants for Quality Improvement in Fruit and Leafy Vegetables," in Growth Regulation and Quality Improvement of Vegetable Crops: Physiological and Molecular Features: Springer, 2025, pp. 457-494.

- M. Mamede, J. Cotas, K. Bahcevandziev, and L. Pereira, "Seaweed polysaccharides in agriculture: A next step towards sustainability," Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 6594, 2023.

- D. Battacharyya, M. Z. Babgohari, P. Rathor, and B. Prithiviraj, "Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture," Scientia horticulturae, vol. 196, pp. 39-48, 2015.

- G. Colla et al., "Protein hydrolysates as biostimulants in horticulture," Scientia Horticulturae, vol. 196, pp. 28-38, 2015.

- Y. Ma, H. Freitas, and M. C. Dias, "Strategies and prospects for biostimulants to alleviate abiotic stress in plants," Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 13, p. 1024243, 2022.

- L. E. Datnoff, W. H. Elmer, and D. M. Huber, Mineral nutrition and plant disease. 2007.

- R. G. Sharp, "A review of the applications of chitin and its derivatives in agriculture to modify plant-microbial interactions and improve crop yields," Agronomy, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 757-793, 2013.

- M. S. Ayilara et al., "Biopesticides as a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides: A case for microbial pesticides, phytopesticides, and nanobiopesticides," Frontiers in microbiology, vol. 14, p. 1040901, 2023.

- F. Apone et al., "A mixture of peptides and sugars derived from plant cell walls increases plant defense responses to stress and attenuates ageing-associated molecular changes in cultured skin cells," Journal of biotechnology, vol. 145, no. 4, pp. 367-376, 2010.

- T. Kejela, "Phytohormone-producing rhizobacteria and their role in plant growth," in New insights into phytohormones: IntechOpen, 2024.

- M. Tejada, B. Rodríguez-Morgado, I. Gómez, L. Franco-Andreu, C. Benítez, and J. Parrado, "Use of biofertilizers obtained from sewage sludges on maize yield," European Journal of Agronomy, vol. 78, pp. 13-19, 2016.

- H. S. Sharma, C. Fleming, C. Selby, J. Rao, and T. Martin, "Plant biostimulants: a review on the processing of macroalgae and use of extracts for crop management to reduce abiotic and biotic stresses," Journal of applied phycology, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 465-490, 2014.

- M. Yuan et al., "Involvement of jasmonic acid, ethylene and salicylic acid signaling pathways behind the systemic resistance induced by Trichoderma longibrachiatum H9 in cucumber," BMC genomics, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 144, 2019.

- H. A. Contreras-Cornejo, L. Macías-Rodríguez, C. Cortés-Penagos, and J. López-Bucio, "Trichoderma virens, a plant beneficial fungus, enhances biomass production and promotes lateral root growth through an auxin-dependent mechanism in Arabidopsis," Plant physiology, vol. 149, no. 3, pp. 1579-1592, 2009.

- Y. Yu, Y. Gui, Z. Li, C. Jiang, J. Guo, and D. Niu, "Induced systemic resistance for improving plant immunity by beneficial microbes," Plants, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 386, 2022.

- J. Köhl, R. Kolnaar, and W. J. Ravensberg, "Mode of action of microbial biological control agents against plant diseases: relevance beyond efficacy," Frontiers in plant science, vol. 10, p. 845, 2019.

- Y. Zhang et al., "Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, no. 42, pp. 18220-18225, 2010.

- C. M. Pieterse, C. Zamioudis, R. L. Berendsen, D. M. Weller, S. C. Van Wees, and P. A. Bakker, "Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes," Annual review of phytopathology, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 347-375, 2014.

- S. Trevisan, O. Francioso, S. Quaggiotti, and S. Nardi, "Humic substances biological activity at the plant-soil interface: from environmental aspects to molecular factors," Plant signaling & behavior, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 635-643, 2010.

- U. Conrath, "Systemic acquired resistance," Plant signaling & behavior, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 179-184, 2006.

- D. Wang, W. Dong, J. Murray, and E. Wang, "Innovation and appropriation in mycorrhizal and rhizobial symbioses," The Plant Cell, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 1573-1599, 2022.

- S. E. Smith and D. J. Read, Mycorrhizal symbiosis. Academic press, 2010.

- A. Ertani, D. Pizzeghello, O. Francioso, P. Sambo, S. Sanchez-Cortes, and S. Nardi, "Capsicum chinensis L. growth and nutraceutical properties are enhanced by biostimulants in a long-term period: Chemical and metabolomic approaches," Frontiers in plant science, vol. 5, p. 375, 2014.

- H. M. Ahmad et al., "Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria eliminate the effect of drought stress in plants: a review," Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 13, p. 875774, 2022.

- Y. Bashan, "Inoculants of plant growth-promoting bacteria for use in agriculture," Biotechnology advances, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 729-770, 1998.

- A. Aydin, C. Kant, and M. Turan, "Humic acid application alleviate salinity stress of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants decreasing membrane leakage," African Journal of Agricultural Research, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 1073-1086, 2012.

- R. Shahzad, R. Tayade, M. Shahid, A. Hussain, M. W. Ali, and B.-W. Yun, "Evaluation potential of PGPR to protect tomato against Fusarium wilt and promote plant growth," PeerJ, vol. 9, p. e11194, 2021.

- G. Ilangumaran and D. L. Smith, "Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in amelioration of salinity stress: a systems biology perspective," Frontiers in plant science, vol. 8, p. 1768, 2017.

- R. Palacio-Rodríguez, J. Sáenz-Mata, R. Trejo-Calzada, P. P. Ochoa-García, and J. G. Arreola-Ávila, "Halotolerant Rhizobacteria promote plant growth and decrease salt stress in Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch," Agronomy, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 3045, 2023.

- K. P. Ramasamy and L. Mahawar, "Coping with salt stress-interaction of halotolerant bacteria in crop plants: A mini review," Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 14, p. 1077561, 2023.

- K. R. Jahed, A. K. Saini, and S. M. Sherif, "Coping with the cold: unveiling cryoprotectants, molecular signaling pathways, and strategies for cold stress resilience," Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 14, p. 1246093, 2023.

- E. Bremer, "Adaptation to changing osmolarity, p 385–391. InSonen-shein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R (ed), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives," ed: ASM Press, Washington, DC, 2002.

- P. Jian, Q. Zha, X. Hui, C. Tong, and D. Zhang, "Research progress of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improving plant resistance to temperature stress," Horticulturae, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 855, 2024.

- A. Sofo et al., "Trichoderma harzianum strain T-22 induces changes in phytohormone levels in cherry rootstocks (Prunus cerasus× P. canescens)," Plant Growth Regulation, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 421-425, 2011.

- O. Ali, A. Ramsubhag, and J. Jayaraman, "Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Implications towards sustainable crop production," Plants, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 531, 2021.

- S. Ali, Y.-S. Moon, M. Hamayun, M. A. Khan, K. Bibi, and I.-J. Lee, "Pragmatic role of microbial plant biostimulants in abiotic stress relief in crop plants," Journal of Plant Interactions, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 705-718, 2022.

- W. Sun and M. H. Shahrajabian, "The application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as microbial biostimulant, sustainable approaches in modern agriculture," Plants, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 3101, 2023.

- N. Buga and M. Petek, "Use of Biostimulants to Alleviate Anoxic Stress in Waterlogged Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata)—A Review," Agriculture, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 2223, 2023.

- S. Ali and W.-C. Kim, "Plant growth promotion under water: decrease of waterlogging-induced ACC and ethylene levels by ACC deaminase-producing bacteria," Frontiers in microbiology, vol. 9, p. 1096, 2018.

- J. Yssel et al., "Assessing the potential of seaweed extracts to improve vegetative, physiological and berry quality parameters in Vitis vinifera cv. Chardonnay under cool climatic conditions," PloS one, vol. 20, no. 9, p. e0331039, 2025.

- R. Tyśkiewicz, A. Nowak, E. Ozimek, and J. Jaroszuk-Ściseł, "Trichoderma: The current status of its application in agriculture for the biocontrol of fungal phytopathogens and stimulation of plant growth," International journal of molecular sciences, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 2329, 2022.

- N. Zhang et al., "Biocontrol mechanisms of Bacillus: Improving the efficiency of green agriculture," Microbial Biotechnology, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 2250-2263, 2023.

- A. Y. Bandara and S. Kang, "Trichoderma application methods differentially affect the tomato growth, rhizomicrobiome, and rhizosphere soil suppressiveness against Fusarium oxysporum," Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 15, p. 1366690, 2024.

- M. Ghonim, "Induction of systemic resistance against Fusarium wilt in tomato by seed treatment with the biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis," 1999.

- M. Gull and F. Y. Hafeez, "Characterization of siderophore producing bacterial strain Pseudomonas fluorescens Mst 8.2 as plant growth promoting and biocontrol agent in wheat," African Journal of Microbiology Research, vol. 6, no. 33, pp. 6308-6318, 2012.

- U. Arinaitwe, S. Rideout, and D. Langston, "Cultural Management of Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans) in Greenhouse Tomatoes Production.

- P. Maini, "The experience of the first biostimulant, based on amino acids and peptides: a short retrospective review on the laboratory researches and the practical results," Fertilitas Agrorum, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 29-43, 2006.

- L. Pereira, J. Cotas, and A. M. Gonçalves, "Seaweed proteins: A step towards sustainability?," Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 8, p. 1123, 2024.

- Q. Wang, M. Liu, Z. Wang, J. Li, K. Liu, and D. Huang, "The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in plant abiotic stress," Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 14, p. 1323881, 2024.

- G. Boyno et al., "Synergistic benefits of AMF: development of sustainable plant defense system," Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 16, p. 1551956, 2025.

- T. Nleya, S. A. Clay, and U. Arinaitwe, "Poor Emergence of Brassica Species in Saline–Sodic Soil Is Improved by Biochar Addition," Agronomy, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 811, 2025.

- U. Arinaitwe, T. M. Nleya, R. Kafle, and S. A. Clay, "Can Beneficial Microbial, and Biochar Amendments Health and Remediate Plant Salt Stress in Saline Soils?," CANVAS 2025, 2025.

- L. Pan and B. Cai, "Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: advances in their physiology, molecular mechanisms and microbial community effects," Microorganisms, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 2904, 2023.

- A. Sharma et al., "Phytohormones regulate accumulation of osmolytes under abiotic stress," Biomolecules, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 285, 2019.

- A. Santaniello et al., "Ascophyllum nodosum seaweed extract alleviates drought stress in Arabidopsis by affecting photosynthetic performance and related gene expression," Frontiers in plant science, vol. 8, p. 1362, 2017.

- M. Hijri, "Microbial-based plant biostimulants," vol. 11, ed: MDPI, 2023, p. 686.

- M. A. Bauer, K. Kainz, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, and F. Madeo, "Microbial wars: competition in ecological niches and within the microbiome," Microbial cell, vol. 5, no. 5, p. 215, 2018.

- M. Atasoy et al., "Exploitation of microbial activities at low pH to enhance planetary health," FEMS Microbiology Reviews, vol. 48, no. 1, p. fuad062, 2024.

- K. Zhang, L. Chen, Y. Li, P. C. Brookes, J. Xu, and Y. Luo, "Interactive effects of soil pH and substrate quality on microbial utilization," European Journal of Soil Biology, vol. 96, p. 103151, 2020.

- A. G. Alghamdi, M. A. Majrashi, and H. M. Ibrahim, "Improving the physical properties and water retention of sandy soils by the synergistic utilization of natural clay deposits and wheat straw," Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 46, 2023.

- U. Arinaitwe, W. H. Frame, M. Reiter, D. Langston, and W. E. T. V. Tech, "Refining N Rates and NUE with Commercial BNF in the US Cotton Belt.

- C. Wang and Y. Kuzyakov, "Mechanisms and implications of bacterial–fungal competition for soil resources," The ISME Journal, vol. 18, no. 1, p. wrae073, 2024.

- R. H. Jayaramaiah et al., "Soil function-microbial diversity relationship is impacted by plant functional groups under climate change," Soil Biology and Biochemistry, vol. 200, p. 109623, 2025.

- P. Nannipieri, S. E. Hannula, G. Pietramellara, M. Schloter, T. Sizmur, and S. I. Pathan, "Legacy effects of rhizodeposits on soil microbiomes: a perspective," Soil Biology and Biochemistry, vol. 184, p. 109107, 2023.

- F. A. Dadzie, A. T. Moles, T. E. Erickson, N. Machado de Lima, and M. Muñoz-Rojas, "Inoculating native microorganisms improved soil function and altered the microbial composition of a degraded soil," Restoration Ecology, vol. 32, no. 2, p. e14025, 2024.

- F. Romero-Perdomo, M. Camelo-Rusinque, P. Criollo-Campos, and R. Bonilla-Buitrago, "Effect of temperature and pH on the biomass production of Azospirillum brasilense C16 isolated from Guinea grass," Pastos Y Forraje, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 231-233, 2015.

- A. L. Koch, "Diffusion the crucial process in many aspects of the biology of bacteria," Advances in microbial ecology, pp. 37-70, 1990.

- T. Long and D. Or, "Aquatic habitats and diffusion constraints affecting microbial coexistence in unsaturated porous media," Water Resources Research, vol. 41, no. 8, 2005.

- U. Arinaitwe, S. A. Clay, and T. Nleya, "Growth, yield, and yield stability of canola in the Northern Great Plains of the United States," Agronomy Journal, vol. 115, no. 2, pp. 744-758, 2023.

- K. Mason-Jones, S. L. Robinson, G. Veen, S. Manzoni, and W. H. van der Putten, "Microbial storage and its implications for soil ecology," The ISME Journal, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 617-629, 2022.

- Q. Lin, H. M. Zhao, and Y. X. Chen, "Effects of 2, 4-dichlorophenol, pentachlorophenol and vegetation on microbial characteristics in a heavy metal polluted soil," Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 551-557, 2007.

- A. Sessitsch, S. Gyamfi, D. Tscherko, M. H. Gerzabek, and E. Kandeler, "Activity of microorganisms in the rhizosphere of herbicide treated and untreated transgenic glufosinate-tolerant and wildtype oilseed rape grown in containment," Plant and Soil, vol. 266, no. 1, pp. 105-116, 2005.

- P. Bajpai, "The control of microbiological problems," Pulp and Paper Industry, p. 103, 2015.

- P. Garbeva, J. Van Elsas, and J. Van Veen, "Rhizosphere microbial community and its response to plant species and soil history," Plant and soil, vol. 302, no. 1, pp. 19-32, 2008.

- U. Arinaitwe, D. N. Yabwalo, and A. Hangamaisho, "Advances in Micronutrients Signaling, Transport, and Integration for Optimizing Cotton Yield," 2025.

- L. E. Forero, J. Grenzer, J. Heinze, C. Schittko, and A. Kulmatiski, "Greenhouse-and field-measured plant-soil feedbacks are not correlated," Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. 7, p. 184, 2019.

- R. COST, "Integrative approaches to enhance reproductive resilience of crops for climate-proof agriculture," Plant stress, vol. 15, p. 100704, 2025.

- D. Camli-Saunders and, C. Villouta, "Root exudates in controlled environment agriculture: composition, function, and future directions," Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 16, p. 1567707, 2025.

- L. Chen and Y. Liu, "The function of root exudates in the root colonization by beneficial soil rhizobacteria," Biology, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 95, 2024.

- M. Moshelion, K.-J. Dietz, I. C. Dodd, B. Muller, and J. E. Lunn, "Guidelines for designing and interpreting drought experiments in controlled conditions," Journal of Experimental Botany, vol. 75, no. 16, pp. 4671-4679, 2024.

- A.R. Dennis, J. F. Nunamaker Jr, and D. R. Vogel, "A comparison of laboratory and field research in the study of electronic meeting systems," Journal of Management Information Systems, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 107-135, 1990.

- H. Aziz, "Comparison between field research and controlled laboratory research," 2017.

- R. M. Calisi and G. E. Bentley, "Lab and field experiments: are they the same animal?," Hormones and behavior, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 1-10, 2009.

- I. Di, Mola; et al., "Plant-based biostimulants influence the agronomical, physiological, and qualitative responses of baby rocket leaves under diverse nitrogen conditions," Plants, vol. 8, no. 11, p. 522, 2019.

- S. Garg et al., "Next generation plant biostimulants & genome sequencing strategies for sustainable agriculture development," Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 15, p. 1439561, 2024.

- U. Arinaitwe, W. Thomason, W. H. Frame, M. S. Reiter, and D. Langston, "Optimizing Maize Agronomic Performance Through Adaptive Management Systems in the Mid-Atlantic United States," Agronomy, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 1059, 2025.

- F. Pérez-Montaño et al., "Plant growth promotion in cereal and leguminous agricultural important plants: from microorganism capacities to crop production," Microbiological research, vol. 169, no. 5-6, pp. 325-336, 2014.

- R. Prasanna et al., "Cyanobacterial inoculation in rice grown under flooded and SRI modes of cultivation elicits differential effects on plant growth and nutrient dynamics," Ecological Engineering, vol. 84, pp. 532-541, 2015.

- S. Bibi, I. Saadaoui, A. Bibi, M. Al-Ghouti, and M. H. Abu-Dieyeh, "Applications, advancements, and challenges of cyanobacteria-based biofertilizers for sustainable agro and ecosystems in arid climates," Bioresource Technology Reports, vol. 25, p. 101789, 2024.

- S. Maliki, M. Al-Zabee, D. M. Muter, M. K. Jabbar, H. Z. Al-Mammori, and M. Sallal, "Mycorrhizal fungi and foliar fe fertilization improved soil microbial indicators and eggplant yield in the arid land soils," Plant Cell Biotechnology and Molecular Biology, vol. 21, no. 71-72, pp. 139-154, 2020.

- Z. Ding, B. Ren, Y. Chen, Q. Yang, and M. Zhang, "Chemical and biological response of four soil types to lime application: an incubation study," Agronomy, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 504, 2023.

- D. Visconti et al., "Compost and microbial biostimulant applications improve plant growth and soil biological fertility of a grass-based phytostabilization system," Environmental Geochemistry and Health, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 787-807, 2023.

- R. Antón-Herrero et al., "Synergistic effects of biochar and biostimulants on nutrient and toxic element uptake by pepper in contaminated soils," Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, vol. 102, no. 1, pp. 167-174, 2022.

- F. Bilias et al., "Effects of sewage sludge biochar and a seaweed extract-based biostimulant on soil properties, nutritional status and antioxidant capacity of lettuce plants in a saline soil with the risk of alkalinization," Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 7271-7287, 2024.

- E. A. Zaghloul et al., "Co-application of organic amendments and natural biostimulants on plants enhances wheat production and defense system under salt-alkali stress," Scientific reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 29742, 2024.

- T. Readyhough, D. A. Neher, and T. Andrews, "Organic amendments alter soil hydrology and belowground microbiome of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)," Microorganisms, vol. 9, no. 8, p. 1561, 2021.

- U. Ogbonnaya and K. T. Semple, "Impact of biochar on organic contaminants in soil: a tool for mitigating risk?," Agronomy, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 349-375, 2013.

- J.W. Bossolani et al., "Long-term lime and gypsum amendment increase nitrogen fixation and decrease nitrification and denitrification gene abundances in the rhizosphere and soil in a tropical no-till intercropping system," Geoderma, vol. 375, p. 114476, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).