1. Introduction

Liquid crystals (LCs) can form highly-organized nanostructures, typically equipped with a π-conjugated backbone and aliphatic chains [[1[

8]. Due to their long-range order and flowability, LCs have been widely studied in liquid-crystal display (LCD) devices [

9], batteries [

10], biosensors, and lasers. The typical chemical structure of LC molecules possesses a π-conjugated backbone, polar groups, and aliphatic chains. Therefore, the molecular shape and the intermolecular weak interactions play significant roles in controlling the stability of LCs. Researchers in supramolecular chemistry have also shown interest in understanding LC performance regulations, as scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) can offer clearer and more direct images of self-assembled LC molecular nanostructures on surfaces with its submolecular resolution [

11,

12,

13,

14]. This resolution enables the observation of nanostructures formed by supramolecular self-assembly, driven by weak interactions such as electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding (HB) [

15,

16,

17], dipole−dipole [

18], and van der Waals (vdW) interactions [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, the principles governing organic molecule self-assembly on 2D surfaces may also apply to their liquid crystal state [

3,

4,

5]. Diaminotriazine (DT) derivatives are widely studied across various fields like LCs [

23], organic electronics [

24], and medical applications [

25], due to their multiple and effective HB sites. Some DT derivatives with LC properties have been reported to form two-dimensional (2D) nanostructures. For example, Meijer et al. demonstrated that π-conjugated oligo-(π-phenylenevinylene) could be used to grow columnar nanowires by creating a supermacrocyclic π-conjugated system [

26,

27]. Additionally, linear and rosette patterns were observed using STM, which depend on the ratio of the side-chain length to the π-conjugated backbone [

27]. The factors of backbone length and the number of branches in the tail chains affecting self-assembly are still unknown. Therefore, the molecular self-assembly behaviors of LCs, in terms of influencing factors, should be further investigated at the molecular level.

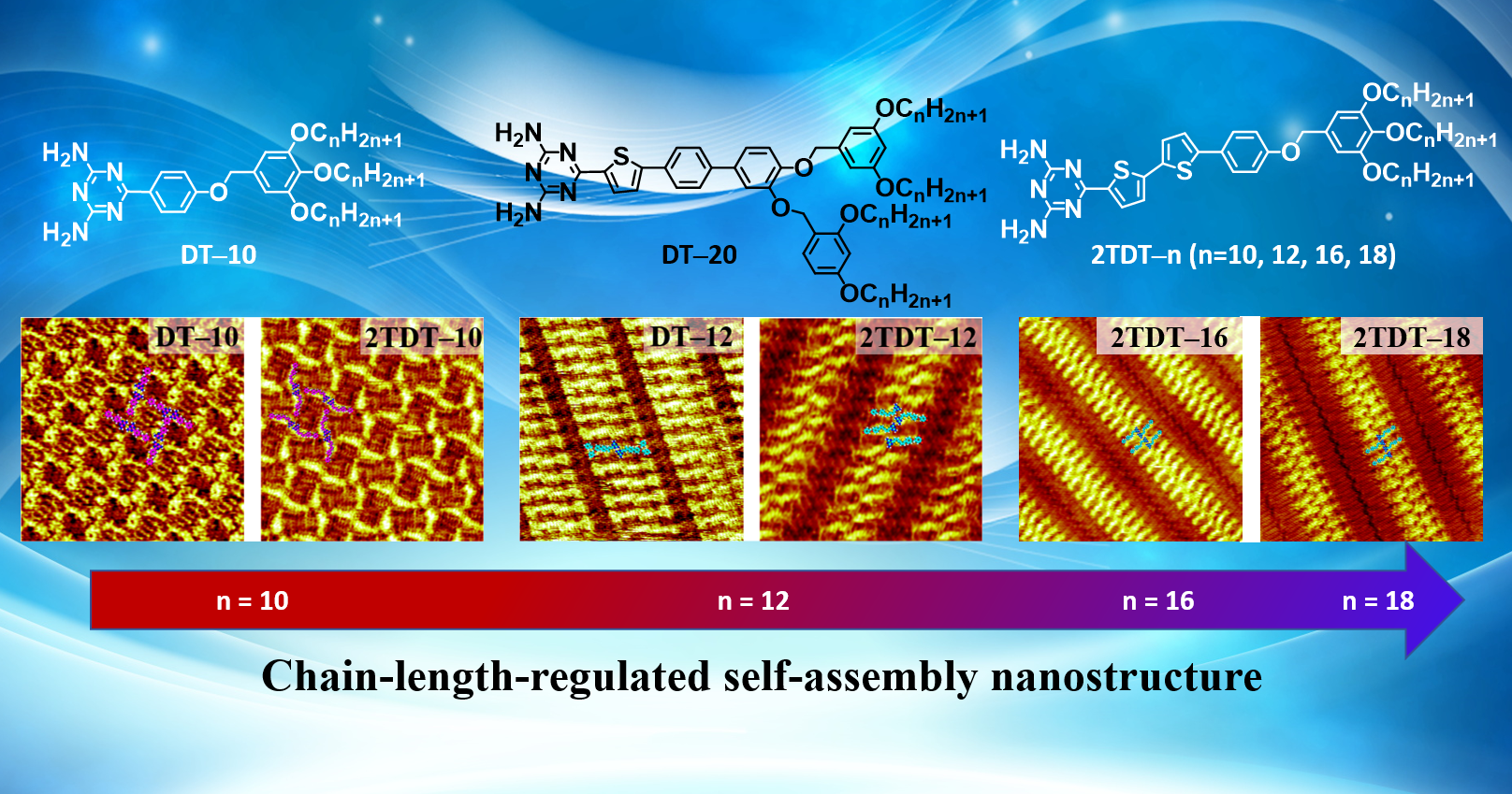

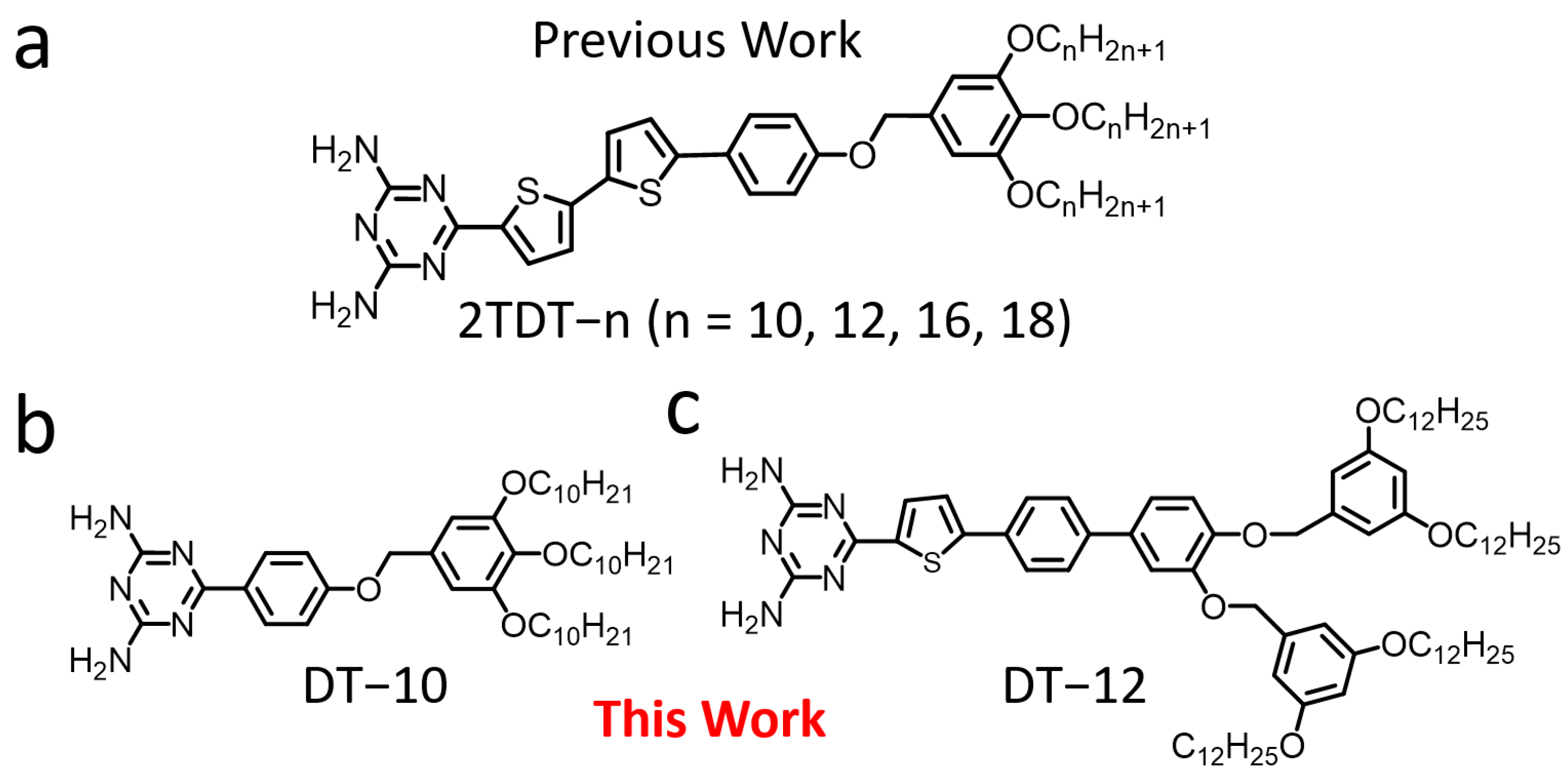

Our previous work reported the chain length effect of DT derivatives (2TDT−n, n = 10, 12, 14, 18) (

Figure 1a) at the 1-octanoic acid (OA)/highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) interface [

28]. The 2TDT−n molecule consists of a bulky polar DT head, a bithiophene backbone, and a trialkoxy chain tail. The chain-length effect on the self-assembled nanostructures of DT derivatives was studied. In this extended microscopic investigation, two DT molecules (DT−10 and DT−12) (

Figure 1b and c) were used to examine how their backbone length and the number of branches in the tail chains influence the formation of self-assembled nanostructures at the OA/HOPG interface using STM. DT−10 features a short backbone and a single tail, while DT−12 has a long backbone and a bifurcated tail. These molecules are similar in structure to our previously reported 2TDT−10 and 2TDT−12, respectively [

28,

29], which allows for comparison of the effects of backbone chain length and tail branch number on self-assembly motifs. Based on STM observations, the key factors driving the motif diversity of DT derivatives are revealed, offering insights into designing surface-confined self-assembled architectures and their LC phases. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to optimize the backbone conformers of DT−10 and DT−12.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The DT−10 and DT−12 molecules were synthesized and supplied by Cheng’s group at Yunnan University [

30]. OA solvent was purchased from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., and dichloromethane was obtained from RichJoint Reagent Co., Ltd. The two molecules mentioned above were used without further purification. Both molecules were dissolved in OA solvents at a target solution concentration of 10

–4 mol/L. A droplet of the sample solution was deposited onto the freshly cleaved HOPG (quality ZYB, Bruker, USA). Subsequently, STM measurements were performed on a Nanoscope IIIa Multimode SPM (Bruker, USA) at room temperature under atmospheric conditions. The tip, made of Pt/Ir material, was mechanically cut. The initial STM images were recorded in a constant current mode, then processed and analyzed using the software Fab Viewer [

31]. All molecular models were constructed with Materials Studio 7.0 software.

2.2. DFT Calculations

Full-geometry optimization and single-point energy calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 with the M06-2X hybrid method and the 6-31+g(d) basis set, which is a split-valence polarized basis set operating in a vacuum environment [

32,

33].

3. Results and Discussion

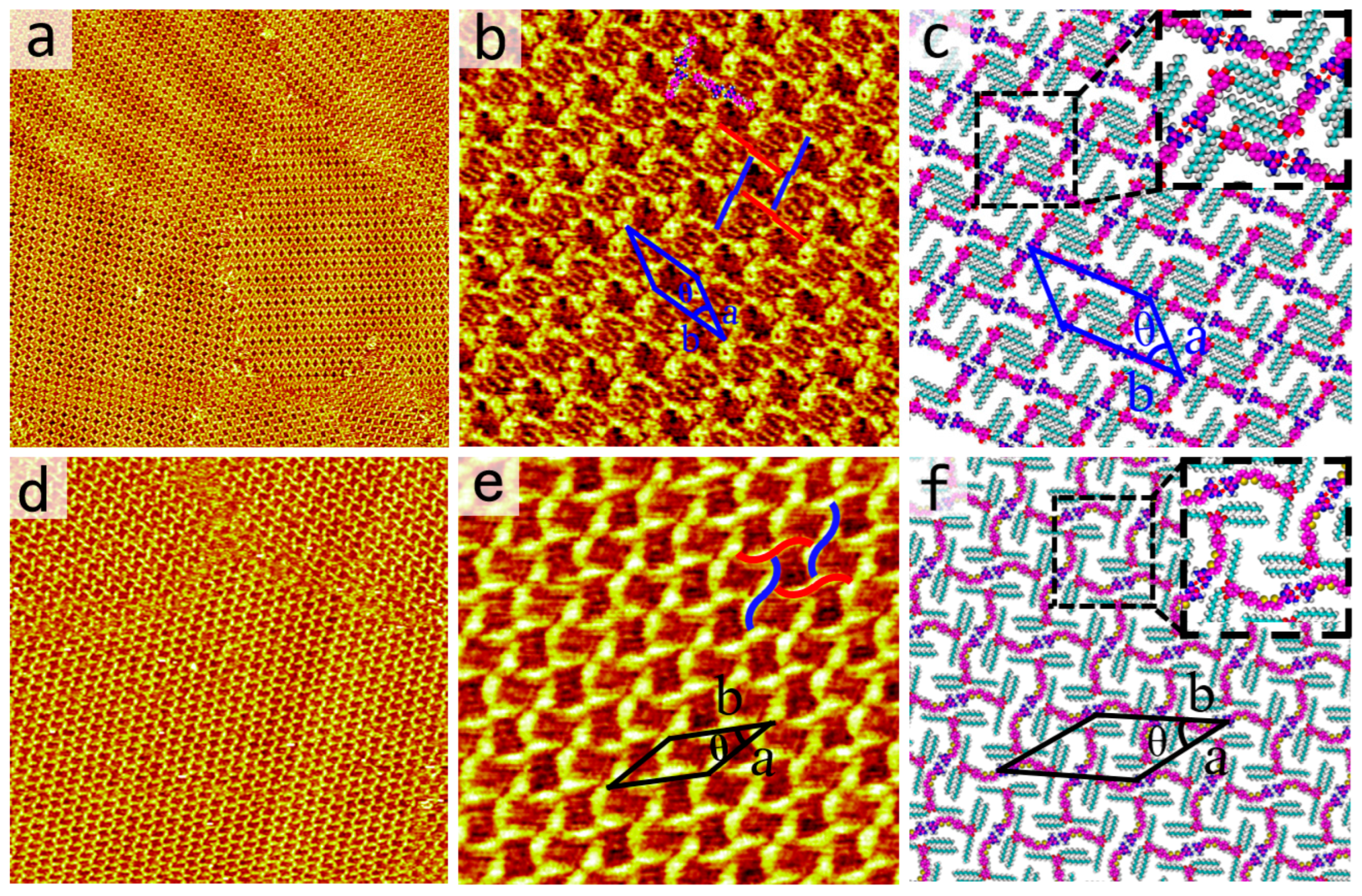

3.1. Self-Assembling Nanostructures of DT Molecules Regulated by π-Conjugated Backbone Length

Inspired by Meijer et al., the ratio of the side chain length to the π-conjugated backbone depends on various motifs in DT derivatives [

27]. The effect of backbone length on the self-assembled nanostructures of DT has been extensively studied. The self-assembly motif of DT−10 is observed in the blow experiment. After dropping a droplet of DT−10 solution in OA solvent onto a freshly cleaved HOPG substrate, the self-assembled structure formed by DT−10 is observed using STM. The large-scale STM image clearly shows that DT−10 molecules organize into a cross-shaped pattern, as depicted in

Figure 2a. The π-conjugated backbones and side chains of DT−10 molecules are distinguishable in STM images due to their differing electron densities. The bright rods represent the backbones of DT−10 molecules with high electron densities, while the dark stripes indicate alkoxy chains with low electron densities. The high-resolution STM image provides more detailed information, as shown in

Figure 2b. It reveals that the backbones of DT−10 molecules are adsorbed on the HOPG surface and form cross-shaped arrangements. Two DT−10 molecules form a dimer with a head-to-head packing arrangement, serving as the fundamental building block for this structure. Additionally, another dimer is located at the center of the first and oriented perpendicularly. Four DT−10 molecules pack in a head-to-tail manner, forming a quadrangular cavity.

For each DT−10 molecule, two side chains run parallel to each other and are perpendicular to the backbone. Both alkoxy side chains rest flat on the graphite surface to enhance interactions with the substrate. The side chains from different molecules interdigitate to maximize van der Waals forces. Based on the STM data, the corresponding molecular models are constructed as shown in

Figure 2c. The enlarged inset at the bottom right highlights N−H···N HBs intermolecular interactions. For each dimer, a pair of N−H···N HBs, originating from the heads of DT−10 molecules, likely stabilizes the dimer. The unit cell and molecular models, overlaid on the high-resolution STM image, include four DT−10 molecules. The parameters of the unit cell are: a = 3.9 ± 0.1 nm, b = 4.8 ± 0.1 nm, and θ = 37 ± 1° (

Table 1).

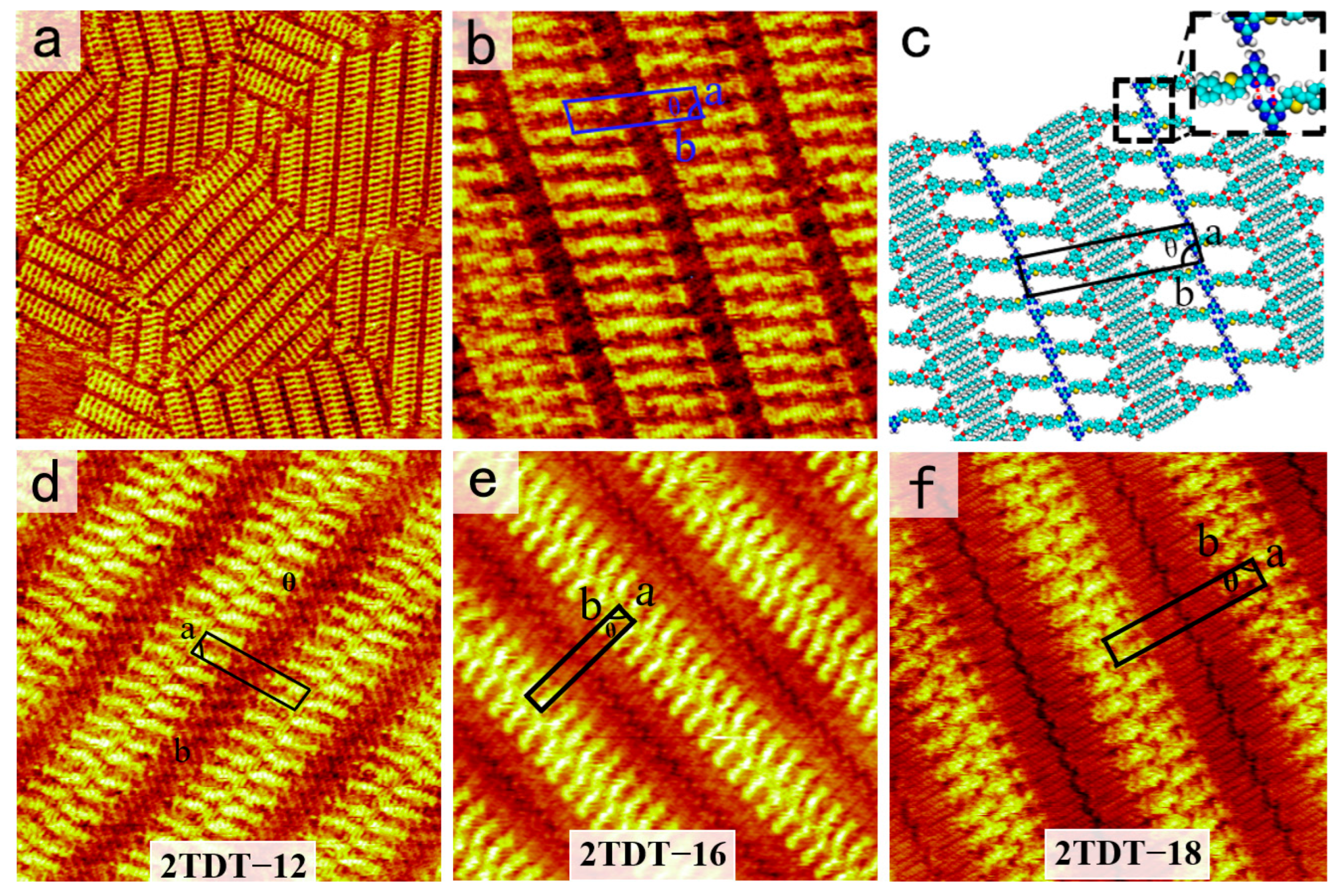

Our previous research showed a structurally similar molecule to 2TDT−10, featuring a bulky polar DT head, a bithiophene backbone, and a tridecalkoxy wedge-shaped chain. 2TDT−10 can form an ordered four-leaved network on the HOPG surface (Figures 2d,e). Each brighter S-shaped feature contains two molecules, with the dimer serving as the self-assembled unit (

Figure 2e). The S-shaped dimer adopts a head-to-head arrangement via a pair of HBs (N–H···N) in an antiparallel orientation. In contrast, the 2TDT−10 molecule has a bithiophene group on its backbone, unlike the DT−10 molecule. Comparing the current nanostructure of DT−10 with that of 2TDT−10 [

28], both molecules show similar arrangements. It is reasonable to suggest that variations in the length of the π-conjugated backbone of DT derivatives do not significantly influence the assembly nanostructures of these molecules.

3.2. How Does the Number of Branches in the Tail Chain Affect the DT Molecular Assembly?

The influence of the number of tail chains on the assembly structure of organic molecules has been reported by Kikkawa et. al. [

34]. While the number of branches in the tail chain of DT derivatives' assembly structure has rarely been reported, this study utilizes DT-12 molecules to investigate how the number of tail chain branches affects self-assembly motifs.

Following the same experimental steps as described above, the self-assembled morphology of DT−12 molecules at the OA/HOPG interface was obtained.

Figure 3a shows a large-scale STM image of the two-row linear pattern formed by DT−12. More details, including the unit cell, are displayed in the high-resolution STM image in

Figure 3b. The backbones of DT−12 molecules are represented by bright bars, while the side chains appear as short, dark stripes. Two DT−12 molecules are packed side by side in an anti-parallel arrangement to form a dimer. These dimers, serving as building blocks, are arranged in a linear pattern, resulting in a two-row linear structure. The angle between a dimer and a lamella is approximately 75°. For each DT−12 dimer, the DT groups facilitate the formation of a pair of N−H···N intermolecular HBs. By carefully counting the number of chains, it is worth noting that the two side chains of each DT−12 molecule adsorb onto the HOPG surface, while the other remains suspended in the solution due to spatial constraints. The alkoxy chains of DT−12 molecules interdigitate and align parallel to each other, maximizing van der Waals forces between the alkyl chains and the substrate. The alkoxy chains between two neighboring stripes are fully interdigitated at an angle of 89 ± 1° from the lamellae. To explain the formation mechanism of the self-assembled structure of DT−12, the proposed molecular model is shown in

Figure 3c. In each dimer, the heads of two DT−12 molecules pack side by side to match their bonding sites better and form a pair of N−H···N intermolecular HBs. The enlarged inset in

Figure 3c depicts these HB interactions as red dashed lines. There are no HB interactions between adjacent dimers due to mismatched bonding sites. The approximate parameters of the unit cell are as follows: a = 1.7 ± 0.1 nm, b = 6.5 ± 0.1 nm, and θ = 84 ± 1°, as listed in

Table 1.

Our previous work documented the self-assembled nanostructure of 2TDT−12, similar to DT−12, at the OA/HOPG interface, which exhibits a two-row linear pattern (

Figure 3d). Compared to the DT−12 and 2TDT−12 molecules, which have similar assembly structures [

28] and both exhibit a two-row linear pattern. In 2TDT−12, the molecular backbone forms a two-row linear pattern, with the DT heads arranged side by side, binding

via a pair of N−H···N HBs with adjacent DT heads. The angle between the lamellar axis, composed of π-conjugated groups, and aliphatic chains is 48 ± 1°. Additionally, there is no interdigitation of side chains in neighboring lamellae. The key difference between DT−12 and 2TDT−12 nanostructure is in the arrangement of the tail chains, specifically whether they are interdigitated. As a result, altering the number of branches in the tail chain can slightly modify the nanostructure of the DT molecules.

4. Role of the DT Moiety

DT units with strong polarity greatly affect the adlayers of DT derivatives on the graphite surface [

28,

29]. Meijer et al. discussed many related studies on DT derivatives by adjusting the ratio between the π-conjugated backbone and the length of the aliphatic chain. They gave a detailed explanation of the typical arrangement of the DT moiety [

15,

27,

29,

35]. Our previous experiments also showed other arrangements of the DT moiety [

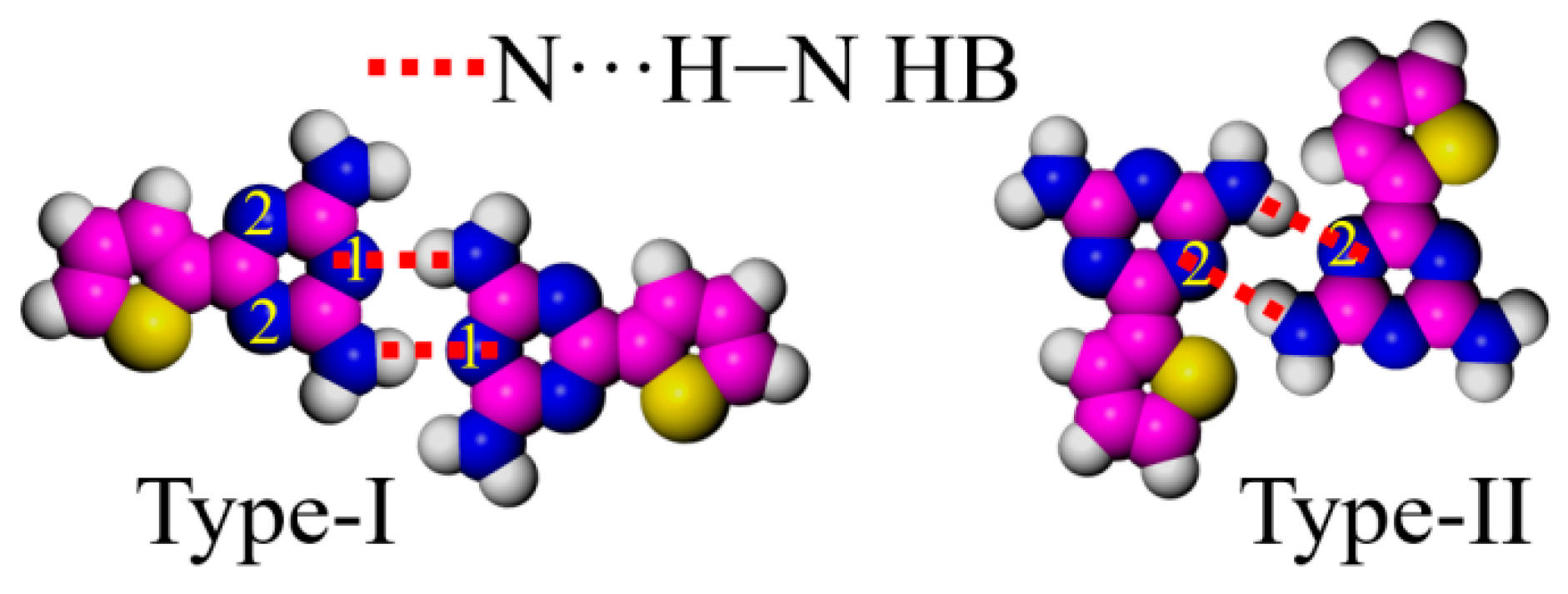

26], though only two types of arrangements are discussed in this paper. To better differentiate the arrangement of DT units, three nitrogen atoms in each DT are labeled as positions 1 and 2 (

Figure 4). Dimer I takes a typical face-to-face structure at the 1,1 sites (type-I), binding with a couple of N···H−N HBs, which are the main interactions creating the cross-shaped pattern in DT−10 and the four-leaf-shaped pattern in 2TDT−10. Dimer II, bonded at 2,2 sites (type-II), mainly appears in a two-row linear pattern in DT−12 and 2TDT−12 adlayers [

28].

Therefore, the bonding models of DT heads in various arrangements depend on the molecular structure. This explanation aligns with Meijer’s reported chain-length effect [

26]. It is well-documented that the length of the side chain plays a key role in adjusting the binding model of DT heads [

28,

36].

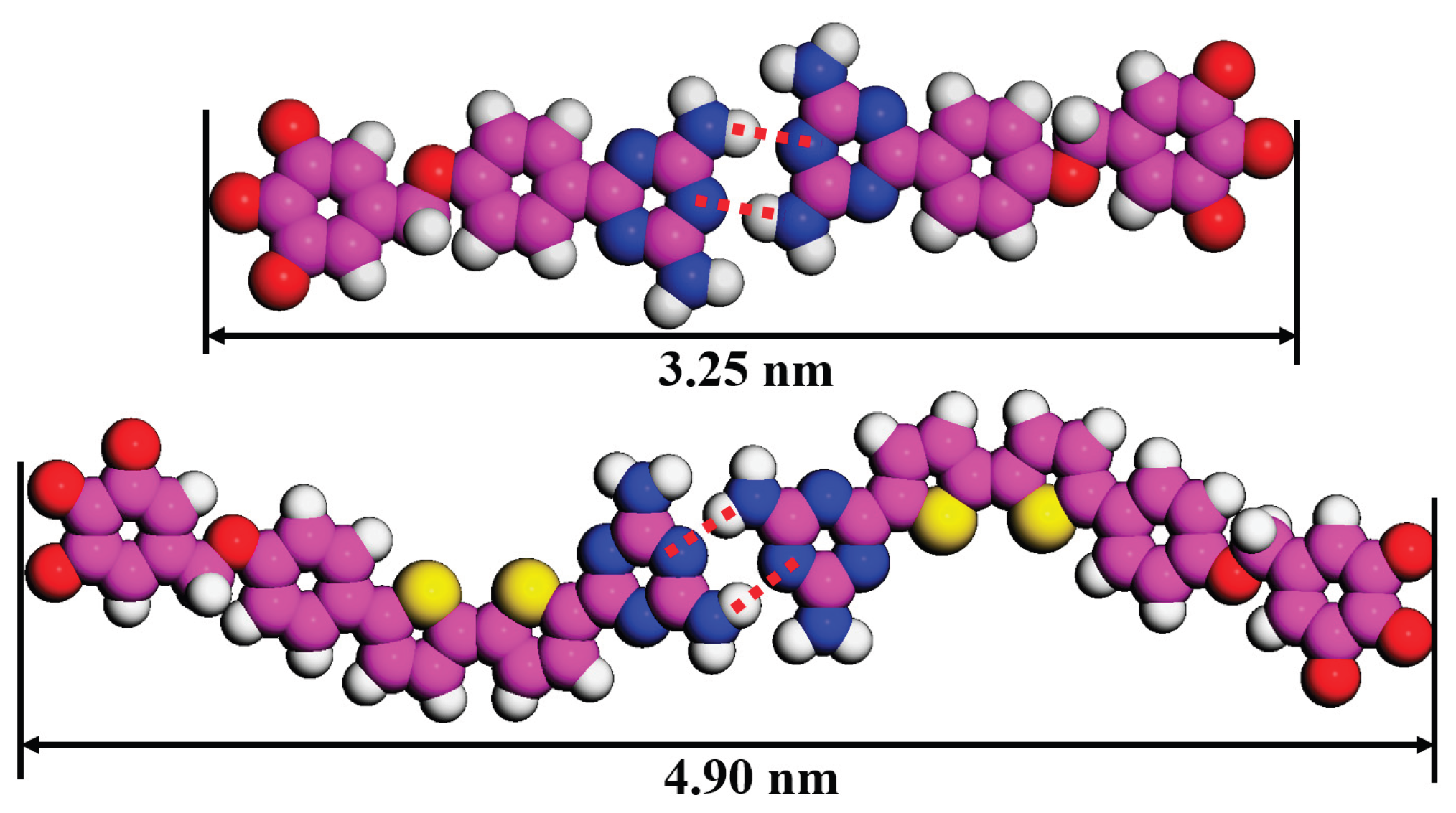

5. Analyzing the Assembly Structures Through Unit Cell Parameters

Table 1 summarizes all patterns of DT molecules and their unit cell parameters. Due to the similar arrangement of cross-shaped (DT−10) and four-leaved (2TDT−10) patterns, the unit cell parameter b is 6.2 nm in the four-leaved pattern along the S-shaped rigid backbone, which is larger than in the cross-shaped pattern (b = 4.8 nm) of DT−10. This difference (1.4 nm) roughly matches the discrepancy between the two π-conjugated backbone lengths (1.65 nm), indicating that when the tridecyloxy ‘‘wedge’’-shaped group acts as an end group, the π-conjugated backbone length cannot significantly tune the self-assembled pattern of DT derivatives. Additionally, comparing the parameters of the two-row linear pattern-I (DT−12) and two-row linear pattern-II (2TDT−12) reveals that the unit cell parameters a and b are nearly equal [

28], and their difference stems from the arrangement of the tail chains, specifically whether they are interdigitated or not. Therefore, variations in the tail chain branch numbers only have a slight influence on the molecular nanostructure of the DT derivatives. When length of side chains of 2TDT−n is further increased to n = 16 and 18. The self-assembly nanostructures of 2TDT−16 and 2TDT−18 both adopt the two-row linear pattern (

Figure 3e,f), the reason is that the interaction between the molecule and the substrate enhances with the length of the side chain, making it difficult for the aliphatic chain to move [

28]. Overall, the chain length plays a crucial role in determine the arrangement of molecules rather than π-conjugated backbone length and tail chain branch numbers. That is, when the tail chain length is n = 10, the DT derivatives tend to form a cross-shape pattern, and when the tail chain length is n ≥ 12, the molecule tends to be arranged in a two-row linear pattern.

Figure 5.

Measured dimers backbone length of DT−10 and 2TDT−10.

Figure 5.

Measured dimers backbone length of DT−10 and 2TDT−10.

6. Conclusions

In summary, two DT molecules (DT−10 and DT−12) are used to investigate how their backbone length and branch number in the tail chains influence self-assembled nanostructures, compared to our previously reported DT diversities (2TDT−n, n = 10, 12, 16, 18), examined using STM at the OA/HOPG interface. The STM results show a similar arrangement between cross-shaped (DT−10) and four-leaved (2TDT−10) patterns. DT−12 and 2TDT−12 form similar structures, both adopting a two-row linear pattern. Therefore, changes in backbone length and branch number slightly affect the molecular nanostructure, emphasizing that the chain length of DT molecules is crucial for tuning their assembly structures. These insights help deepen understanding of self-assembly behaviors, which could be particularly important for controlling the performance of LCs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and X.Z.; methodology, Y.W.; software, Y.W.; validation, Y.W., Z.Z. and Y.H.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; investigation, Y.W.; resources, Z.Z.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, X.M.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, X.M.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 22172055 and 22261055, and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, grant number 2022A1515011892, the Guangdong-Taiwan Technology Cooperation Projects in Guangdong Province, grant number 2024A0505050044, and the SSL Science and Technology Commissioner Program, grant number 20234368-01KCJ-G.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Dongguan Key Laboratory of Digital and Intelligent Equipment for Emergency Industry and the supercomputing platform at South China University of Technology are thanked for providing the computational resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andy; Fuh, Y.G.; Cheng, K.T.; Lee, C.R.; Fuh, Y.G.; Cheng, K.T. Liquid crystals biphotonic recording effect of polarization gratings based on dye-doped liquid crystal films biphotonic recording effect of polarization gratings based on dye—doped liquid crystal films. Liq. Cryst. 2007, 34, 389–393.

- Höger, S.; Cheng, X. H.; Ramminger, A. D.; Enkelmann, V.; Rapp, A.; Mondeshki, M.; & Schnell, I. Discotic liquid crystals with an inverted structure. Angew. Chem. Inter. Edit. 2005, 44, 2801–2805.

- Zhang, C.; Yu, P.; Zhao, J.; Liang, M.; He, Z.; Miao, Z. Molecular engineering controlled electric-optical performance of polymer dispersed liquid crystals. Liq. Cryst. 2024, 51, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.U.; Jing, A.J.; Monsdorf, B.; Graham, M.J.; Harris, F.W.; Cheng, S.Z.D. Self-assembly of chemically linked rod-disc mesogenic liquid crystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkheijm, P.; Miura, A.; Zdanowska, M.; Hoeben, F.J.M.; De Feyter, S.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; De Schryver, F.C.; Meijer, E.W. π-Conjugated oligo-(p-phenylenevinylene) rosettes and their tubular self-assembly. Angew. Chem. Inter. Edit. 2004, 43, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisula, W.; Tomovi, E.; Wegner, M.; Graf, R.; Pouderoijen, M.J.; Meijer, E.W.; Schenning, A.P.H.J. Liquid crystalline hydrogen bonded oligo(p-phenylenevinylene)s. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 2968–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, A.; Jonkheijm, P.; De Feyter, S.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; Meijer, E.W.; De Schryver, F.C. 2D Self-assembly of oligo(π-phenylene vinylene) derivatives: from dimers to chiral rosettes. Small 2005, 1, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, K. Photoalignment of liquid-crystal systems. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1847–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Kim, D.S.; Ju, J.H.; Cho, W.H.; Kim, J.E.; Suh, K.S. Static charge-induced orientation of liquid crystals in LCD panels. IEEE 2010, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Lu, F.; Li, Y.R.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, X.Z.; Li, Q.; Gao, X.P. Gyroid liquid crystals as quasi-solid-state electrolytes toward ultrastable zinc batteries. ACS nano 2024, 18, 7633–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, D.M.; Venkataraman, B.; Flynn, G.W. STM investigations of organic molecules physisorbed at the liquid-solid interface. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 1600–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.T.; Miao, X.R.; Deng, W.L. Site-selection and recognition of aromatic carboxylic acid in response to coronene and pyridine derivative. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabel, A.; Heinz, R.; Rabe, J.; Wegner, G.; De Schryver, F.; Corens, D.; Dehaen, W.; Süling, C. STM investigation of 2D crystals of anthrone derivatives on graphite: analysis of molecular structure and dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 8690–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tersoff, J.; Hamann, D.R. Theory and Application for the Scanning Tunneling Microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 1998–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbesma, R.R.; Meijer, E.B. Self-assembly of well-defined structures by hydrogen bonding. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 30, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B.; Singh, G.; Gupta, R.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Solovev, A.A.; Pombeiro, A.J.L.; Ren, P. Hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs): Multifunctional material on analytical monitoring. Trac-Trend. Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, B.; Dong, M.Q.; Miao, X.R.; Peng, S.; Wu, Y.C.; Miao, K.; Hu, Y.; Deng, W.L. Cooperation and competition between halogen bonding and van der Waals forces in supramolecular engineering at the aliphatic hydrocarbon/graphite interface: position and number of bromine group effects. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.Q.; Miao, K.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J.T.; Li, J.X.; Pang, P.; Miao, X.R.; Deng, W.L. Cooperating dipole–dipole and van der Waals interactions driven 2D self-assembly of fluorenone derivatives: ester chain length effect. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 31113–31120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Deng, X.; Wang, D.; Pei, J.; Wan, L.J. Chiral hierarchical molecular nanostructures on two-dimensional surface by controllable trinary self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 21010–21015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Fu, W.F.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.M.; Sheng, C. Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Deng, K.; Zeng, Q.D.; Shu, L. J. Donor–acceptor conjugated macrocycles: Synthesis and host–guest coassembly with fullerene toward photovoltaic application. ACS nano 2017, 11, 11701–11713. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.T.; Guan, L.; Zhu, X.Y.; Zeng, Q.D.; Wang, C. Submolecular observation of photosensitive macrocycles and their isomerization effects on host-guest network. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6174–6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, X.R.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Deng, W.L. Tuning the packing density of host molecular self-assemblies at the solid–liquid interface using guest molecule. Chem. Commun. 2009, 46, 8830–8830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maly, K.E.; Dauphin, C.; Wuest, J.D. Self-assembly of columnar mesophases from diaminotriazines. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 4695–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathi, S.K.; Joseph, J. Thymine-induced dynamic switching of self-assembled nanofibers in diaminotriazine-functionalized tetraphenylethylene derivatives: implications for one-dimensional molecular devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 3018–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łączkowski, K.Z.; Anusiak, J.; Świtalska, M.; Dzitko, K.; Cytarska, J.; Baranowska-Łączkowska, A.; Plech, T.; Paneth, A.; Wietrzyk, J.; Białczyk, J. Synthesis, molecular docking, ctDNA interaction, DFT calculation and evaluation of antiproliferative and anti-Toxoplasma gondii activities of 2, 4-diaminotriazine-thiazole derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2018, 27, 1131–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, A.; Jonkheijm, P.; De Feyter, S.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; Meijer, E.W.; De Schryver, F.C. 2D self-assembly of oligo(π-phenylene vinylene) derivatives: From dimers to chiral rosettes. Small 2010, 1, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesquière, A.; Jonkheijm, P.; Hoeben, F.J.M.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; De Feyter, S.; De Schryver, F.C.; Meijer, E.W. 2D-structures of quadruple hydrogen bonded oligo(π-phenylenevinylene)s on graphite: self-assembly behavior and expression of chirality. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Ke, M.; Zeng, X.; Miao, X.; Cheng, X.; Deng, W. Chain-length-and concentration-dependent isomerization of bithiophenyl-based diaminotriazine derivatives in two-dimensional polymorphic self-assembly. Langmuir 2022, 38, 7005–7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Pang, P.; Li, B.; Miao, X.; Cheng, X.; Deng, W. Template-assisted 2D self-assembled chiral Kagomé network for selective adsorption of coronene. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13991–13994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.P.; Chang, Q.; Su, F.; Cao, Y.; Liu, F.; Cheng, X.H. Rodlike 4,6-diamino-1,3,5-triazine derivatives, effect of the core length on mesophase behavior and their application as LE-LCD device. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 346, 117879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silly, F. A robust method for processing scanning probe microscopy images and determining nanoobject position and dimensions. J. Microsc-Oxford 2010, 236, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R. Atoms in molecules: a quantum theory. J. mol. struct.: theochem. 1994, 360, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y.; Koyama, E.; Tsuzuki, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Miyake, K.; Tokuhisa, H.; Kanesato, M. Self-assembly of bipyridine derivatives at solid/liquid interface: Effects of the number of peripheral alkyl chains and metal coordination on the two-dimensional structures. Surf. Sci. 2007, 601, 2520–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; De Cat, I.; Van Averbeke, B.; Lin, J.; Wang, G.; Xu, H.; Lazzaroni, R.; Beljonne, D.; Meijer, E.W.; Schenning, A.P.H.J. Nucleoside-assisted self-assembly of oligo(π-phenylenevinylene)s at liquid/solid interface: chirality and nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17764–17771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gao, H.; Li, T.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, X.H. Bisthiophene/triazole based 4, 6-diamino-1, 3, 5-triazine triblock polyphiles: Synthesis, self-assembly and metal binding properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1193, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).