Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: From Unicellular to Multicellular Synthetic Biology

2. From Circuits to Symphonies: A Paradigm Shift

3. Microbial Communication: The Language of Microbial Symphonies

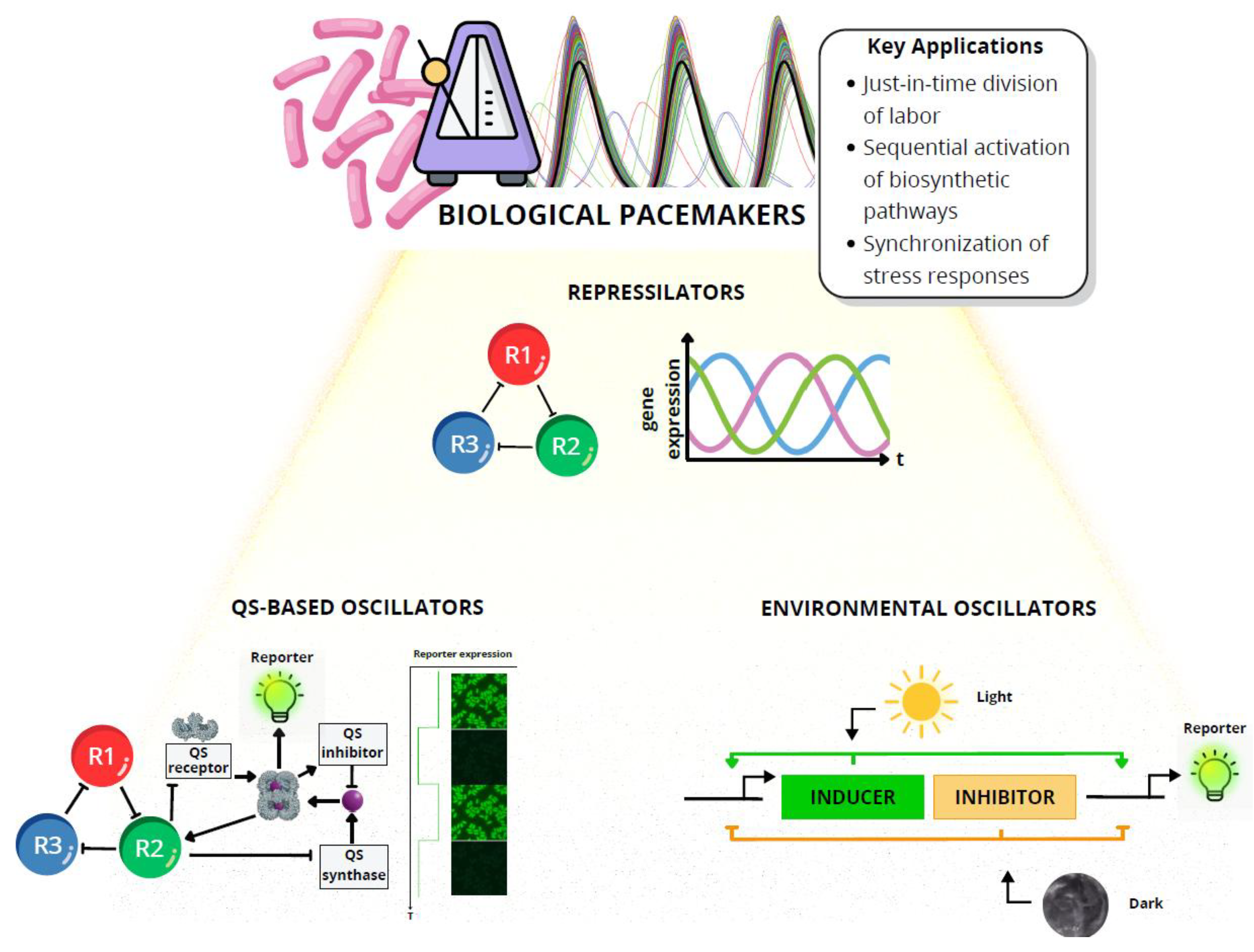

4. Temporal Synchronization: Setting the Rhythm of Microbial Symphonies

5. Synthetic Ecology: Ecological Dynamics as the Harmony of the Symphony

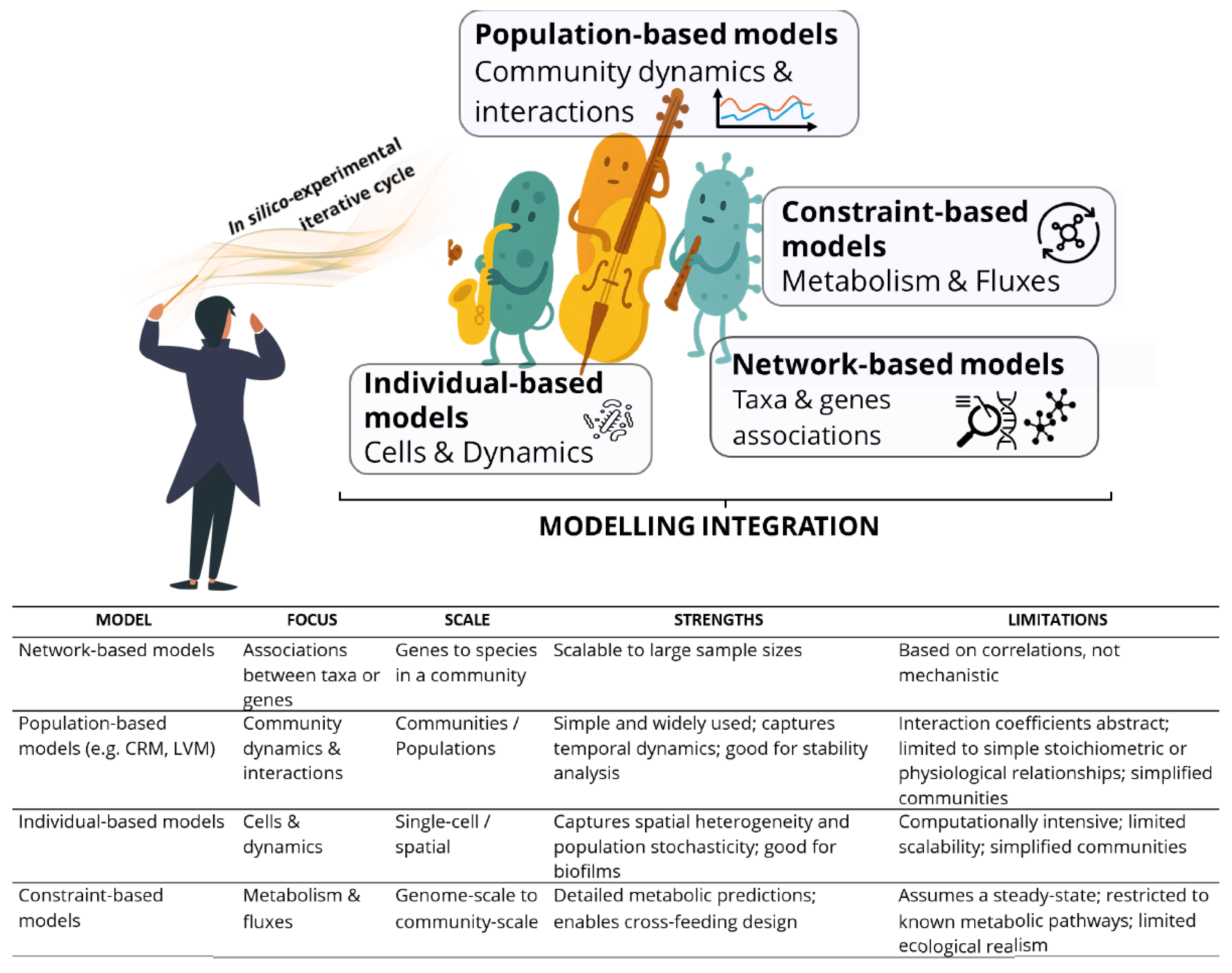

6. Data Integration and Modelling: The Conductor of Synthetic Microbial Orchestras

7. Future Perspectives and Conclusion: The Symphony of Multimicrobial Synthetic Biology

Acknowledgments

References

- Contreras-Salgado, E.A.; Sánchez-Morán, A.G.; Rodríguez-Preciado, S.Y.; Sifuentes-Franco, S.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R.; Macías-Barragán, J.; Díaz-Zaragoza, M. Multifaceted Applications of Synthetic Microbial Communities: Advances in Biomedicine, Bioremediation, and Industry. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1709–1727. [CrossRef]

- Bittihn, P.; Din, M.O.; Tsimring, L.S.; Hasty, J. Rational engineering of synthetic microbial systems: from single cells to consortia. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 45, 92–99. [CrossRef]

- Rapp, K.M.; Jenkins, J.P.; Betenbaugh, M.J. Partners for life: building microbial consortia for the future. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 66, 292–300. [CrossRef]

- Ben Said, S.; Tecon, R.; Borer, B.; Or, D. The engineering of spatially linked microbial consortia – potential and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Mccarty, N.S.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Synthetic biology tools to engineer microbial communities for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 181–197. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, K.; You, L.; Arnold, F.H. Engineering microbial consortia: a new frontier in synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 483–489. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.J. Advancing microbial engineering through synthetic biology. J. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e2503100. [CrossRef]

- León-Buitimea, A.; Balderas-Cisneros, F.d.J.; Garza-Cárdenas, C.R.; Garza-Cervantes, J.A.; Morones-Ramírez, J.R. Synthetic Biology Tools for Engineering Microbial Cells to Fight Superbugs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 869206. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, A.; Li, J.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Xu, P.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Towards next-generation model microorganism chassis for biomanufacturing. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 9095–9108. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Salvador, M.; Saunders, E.; González, J.; Avignone-Rossa, C.; Jiménez, J.I.; Pinheiro, V.B. Properties of alternative microbial hosts used in synthetic biology: towards the design of a modular chassis. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 303–313. [CrossRef]

- Wintermute, E.H.; Silver, P.A. Dynamics in the mixed microbial concourse. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2603–2614. [CrossRef]

- Konopka, A. What is microbial community ecology? ISME J 3, 1223–1230 (2009).

- Berg, N.I.v.D.; Machado, D.; Santos, S.; Rocha, I.; Chacón, J.; Harcombe, W.; Mitri, S.; Patil, K.R. Ecological modelling approaches for predicting emergent properties in microbial communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 855–865. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jin, X.; Glass, D.S.; Riedel-Kruse, I.H. Engineering and modeling of multicellular morphologies and patterns. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2020, 63, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Raajaraam, L.; Raman, K. Modelling microbial communities: Harnessing consortia for biotechnological applications. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 3892–3907. [CrossRef]

- Sgobba, E.; Wendisch, V.F. Synthetic microbial consortia for small molecule production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Men, Y. Synthetic microbial consortia for biosynthesis and biodegradation: promises and challenges. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 1343–1358. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Liu, C.; Song, H.; Ding, M.; Du, J.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, Y. Design, analysis and application of synthetic microbial consortia. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2016, 1, 109–117. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Marquez, J.C.F.; Nascimento, M.D.; Zehr, J.P.; Curatti, L. Genetic engineering of multispecies microbial cell factories as an alternative for bioenergy production. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 521–529. [CrossRef]

- Shong, J.; Diaz, M.R.J.; Collins, C.H. Towards synthetic microbial consortia for bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 798–802. [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, E.; Scher, E. Models for DNA Design Tools: The Trouble with Metaphors Is That They Don’t Go Away. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 2635–2641. [CrossRef]

- McLeod, C.; Nerlich, B. Synthetic biology, metaphors and responsibility. Life Sci. Soc. Policy 2017, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.J.Y.; Woo, S.S.; Sarpeshkar, R. Synthetic Biology: A Unifying View and Review Using Analog Circuits. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2015, 9, 453–474. [CrossRef]

- Boudry, M.; Pigliucci, M. The mismeasure of machine: Synthetic biology and the trouble with engineering metaphors. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part C: Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2013, 44, 660–668. [CrossRef]

- Alfinito, E.; Beccaria, M. Resonance for Life: Metabolism and Social Interactions in Bacterial Communities. Biophysica 2025, 5, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rafieenia, R.; Atkinson, E.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Division of labor for substrate utilization in natural and synthetic microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 75, 102706. [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, R.; Wu, F.; Zhang, C.; Bewick, S.; Karig, D.; You, L. Metabolic division of labor in microbial systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 2526–2531. [CrossRef]

- Bassler, B.L.; Losick, R. Bacterially Speaking. Cell 2006, 125, 237–246. [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, E. Metaphor in Science. in A Companion to the Philosophy of Science 277–282 (Wiley, 2017). [CrossRef]

- Grinter, A. Metaphors in Science: Lessons for Developing an Ecological Paradigm. Telos 2020, 2020, 77–91. [CrossRef]

- Kepler, J. Ioannis Keppleri Harmonices Mundi Libri V. (sumptibus Godofredi Tampachii ..., excudebat Ioannes Plancus, 1619). [CrossRef]

- Brittan, F. The Neural Orchestra: Cognitive Instrumentalities. J. Am. Music. Soc. 2024, 77, 1–63. [CrossRef]

- Boo, A.; Amaro, R.L.; Stan, G.-B. Quorum sensing in synthetic biology: A review. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2021, 28. [CrossRef]

- Abisado, R.G.; Benomar, S.; Klaus, J.R.; Dandekar, A.A.; Chandler, J.R.; Garsin, D.A. Bacterial Quorum Sensing and Microbial Community Interactions. mBio 2018, 9, e02331-17. [CrossRef]

- An, J.H.; Goo, E.; Kim, H.; Seo, Y.-S.; Hwang, I. Bacterial quorum sensing and metabolic slowing in a cooperative population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 14912–14917. [CrossRef]

- Hooshangi, S.; E Bentley, W. From unicellular properties to multicellular behavior: bacteria quorum sensing circuitry and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 550–555. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, R.; Zhang, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Construction of stable microbial consortia for effective biochemical synthesis. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1430–1441. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiao, J.; Sun, T.; Yu, F.; Zhang, K.; Feng, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, B.; Cheng, L. Synthetic microbial consortia with programmable ecological interactions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 1608–1621. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Qiao, J. Vertical and horizontal quorum-sensing-based multicellular communications. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 1130–1142. [CrossRef]

- Winkle, J.J.; Karamched, B.R.; Bennett, M.R.; Ott, W.; Josić, K.; You, L. Emergent spatiotemporal population dynamics with cell-length control of synthetic microbial consortia. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009381. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, K.; Bentley, W.E. Synthetic Biology for Manipulating Quorum Sensing in Microbial Consortia. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 633–643. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Chen, Y.; Hirning, A.J.; Alnahhas, R.N.; Josić, K.; Bennett, M.R. Long-range temporal coordination of gene expression in synthetic microbial consortia. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 1102–1109. [CrossRef]

- Kylilis, N.; Tuza, Z.A.; Stan, G.-B.; Polizzi, K.M. Tools for engineering coordinated system behaviour in synthetic microbial consortia. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Parkin, J. M., Hsiao, V. & Murray, R. M. Engineering pulsatile communication in bacterial consortia. bioRxiv 111906, (2017).

- Scott, S.R.; Hasty, J. Quorum Sensing Communication Modules for Microbial Consortia. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 969–977. [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Yu, Z.; Sheng, H.; Shen, X.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Q. Redesigning regulatory components of quorum-sensing system for diverse metabolic control. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Miano, A.; Liao, M.J.; Hasty, J. Inducible cell-to-cell signaling for tunable dynamics in microbial communities. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bacchus, W.; Fussenegger, M. Engineering of synthetic intercellular communication systems. Metab. Eng. 2013, 16, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Marchand, N. & Collins, C. H. Peptide-based communication system enables Escherichia coli to Bacillus megaterium interspecies signaling. Biotechnol Bioeng 110, 3003–3012 (2013).

- Fetzner, S. Quorum quenching enzymes. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 201, 2–14. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, A.; Shukla, A.; Patel, D. Quorum Sensing and Quorum Quenching: Two sides of the same coin. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 123. [CrossRef]

- Pezzoni, M.; Pizarro, R.A.; Costa, C.S. Role of quorum sensing in UVA-induced biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 2020, 166, 735–750. [CrossRef]

- Tanouchi, Y.; Tu, D.; Kim, J.; You, L.; Asthagiri, A. Noise Reduction by Diffusional Dissipation in a Minimal Quorum Sensing Motif. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000167–e1000167. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kim, J.K.; Hirning, A.J.; Josić, K.; Bennett, M.R. Emergent genetic oscillations in a synthetic microbial consortium. Science 2015, 349, 986–989. [CrossRef]

- McMillen, D.; Kopell, N.; Hasty, J.; Collins, J.J. Synchronizing genetic relaxation oscillators by intercell signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 679–684. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Bao, M.; Duan, X.; Zhou, P.; Chen, C.; Gao, J.; Cheng, S.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhao, Z. Developing a pathway-independent and full-autonomous global resource allocation strategy to dynamically switching phenotypic states. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Jiang, W.; Mu, Y.; Huang, H.; Su, T.; Luo, Y.; Liang, Q.; Qi, Q. Quorum Sensing-Based Dual-Function Switch and Its Application in Solving Two Key Metabolic Engineering Problems. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A.C.d.V.; Nieto, C.; Pajot, H.F.; Bertini, E.V.; Mac Cormack, W.; de Figueroa, L.I.C.; Nieto-Peñalver, C.G. Inactivation of bacterial quorum sensing signals N-acyl homoserine lactones is widespread in yeasts. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S. S., Bedekar, A. A. & Rao, C. V. Quorum Sensing in Yeast. in 235–250 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, X. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1250151. [CrossRef]

- Zargar, A.; Quan, D.N.; Bentley, W.E. Enhancing Intercellular Coordination: Rewiring Quorum Sensing Networks for Increased Protein Expression through Autonomous Induction. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 923–928. [CrossRef]

- Geske, G.D.; O’nEill, J.C.; Blackwell, H.E. Expanding dialogues: from natural autoinducers to non-natural analogues that modulate quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1432–1447. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, J. & Suga, H. Custom Synthesis of Autoinducers and Their Analogues. in 265–274 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Smith, J.A.I.; Wang, J.; Stewart, J.E.; Bentley, W.E.; Sintim, H.O. Synthetic Analogs Tailor Native AI-2 Signaling Across Bacterial Species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11141–11150. [CrossRef]

- Wynendaele, E.; Bronselaer, A.; Nielandt, J.; D’hOndt, M.; Stalmans, S.; Bracke, N.; Verbeke, F.; Van De Wiele, C.; De Tré, G.; De Spiegeleer, B. Quorumpeps database: chemical space, microbial origin and functionality of quorum sensing peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D655–D659. [CrossRef]

- Ziesack, M.; Gibson, T.; Oliver, J.K.W.; Shumaker, A.M.; Hsu, B.B.; Riglar, D.T.; Giessen, T.W.; DiBenedetto, N.V.; Bry, L.; Way, J.C.; et al. Engineered Interspecies Amino Acid Cross-Feeding Increases Population Evenness in a Synthetic Bacterial Consortium. mSystems 2019, 4. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, S.; Dong, Y.; Fan, H.; Bai, Z.; Zhuang, X. Engineering Microbial Consortia towards Bioremediation. Water 2021, 13, 2928. [CrossRef]

- Kerner, A.; Park, J.; Williams, A.; Lin, X.N.; Sandler, S.J. A Programmable Escherichia coli Consortium via Tunable Symbiosis. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e34032. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Bian, Z. & Wang, Y. Biofilm formation and inhibition mediated by bacterial quorum sensing. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 106, 6365–6381 (2022).

- Tan, C.H.; Oh, H.-S.; Sheraton, V.M.; Mancini, E.; Loo, S.C.J.; Kjelleberg, S.; Sloot, P.M.A.; Rice, S.A. Convection and the Extracellular Matrix Dictate Inter- and Intra-Biofilm Quorum Sensing Communication in Environmental Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6730–6740. [CrossRef]

- Goo, E.; An, J.H.; Kang, Y.; Hwang, I. Control of bacterial metabolism by quorum sensing. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 567–576. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Reizman, I.M.B.; Reisch, C.R.; Prather, K.L.J. Dynamic regulation of metabolic flux in engineered bacteria using a pathway-independent quorum-sensing circuit. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Grandel, N.E.; Gamas, K.R.; Bennett, M.R. Control of synthetic microbial consortia in time, space, and composition. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 1095–1105. [CrossRef]

- Fussenegger, M. Synchronized bacterial clocks. Nature 2010, 463, 301–302. [CrossRef]

- Ronda, C.; Wang, H.H. Engineering temporal dynamics in microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 65, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, L.; Cohen-Luria, R.; Wagner, N.; Ashkenasy, G. Robustness of synthetic circadian clocks to multiple environmental changes. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5672–5675. [CrossRef]

- Tayar, A.M.; Karzbrun, E.; Noireaux, V.; Bar-Ziv, R.H. Synchrony and pattern formation of coupled genetic oscillators on a chip of artificial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 11609–11614. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Payne, S.; Tan, C.; You, L. Programming microbial population dynamics by engineered cell–cell communication. Biotechnol. J. 2011, 6, 837–849. [CrossRef]

- Curatolo, A.I.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, C.; Daerr, A.; Tailleur, J.; Huang, J. Cooperative pattern formation in multi-component bacterial systems through reciprocal motility regulation. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 1152–1157. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, Q. Systems and synthetic biology approaches in understanding biological oscillators. Quant. Biol. 2017, 6, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Potvin-Trottier, L., Lord, N. D., Vinnicombe, G. & Paulsson, J. Synchronous long-term oscillations in a synthetic gene circuit. Nature 538, 514–517 (2016).

- Nguyen, J.; Lara-Gutiérrez, J.; Stocker, R. Environmental fluctuations and their effects on microbial communities, populations and individuals. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 45. [CrossRef]

- Cookson, N.A.; Tsimring, L.S.; Hasty, J. The pedestrian watchmaker: Genetic clocks from engineered oscillators. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3931–3937. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, C.V.; Prather, K.L.J. Development of an autonomous and bifunctional quorum-sensing circuit for metabolic flux control in engineered Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 25562–25568. [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Zhou, T. Communication-induced multistability and multirhythmicity in a synthetic multicellular system. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 83, 051907. [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Qian, Y.; Stewart, P.S.; Lu, T. De novo engineering of a bacterial lifestyle program. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 19, 488–497. [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, G.S.; Maddamsetti, R.; Son, H.-I.; Wilson, M.L.; Davis, H.M.; You, L. Programming Dynamic Division of Labor Using Horizontal Gene Transfer. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1142–1151. [CrossRef]

- Takhaveev, V.; Özsezen, S.; Smith, E.N.; Zylstra, A.; Chaillet, M.L.; Chen, H.; Papagiannakis, A.; Milias-Argeitis, A.; Heinemann, M. Temporal segregation of biosynthetic processes is responsible for metabolic oscillations during the budding yeast cell cycle. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 294–313. [CrossRef]

- Roell, G.W.; Zha, J.; Carr, R.R.; Koffas, M.A.; Fong, S.S.; Tang, Y.J. Engineering microbial consortia by division of labor. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Deter, H.S.; Lu, T. Engineering microbial consortia with rationally designed cellular interactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 76, 102730–102730. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.M.; Zhang, Y.; Mehl, J.; Park, H.; Lalwani, M.A.; Toettcher, J.E.; Avalos, J.L. Optogenetic regulation of engineered cellular metabolism for microbial chemical production. Nature 2018, 555, 683–687. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, V.; Wissel, C. Babel, or the ecological stability discussions: an inventory and analysis of terminology and a guide for avoiding confusion. Oecologia 1997, 109, 323–334. [CrossRef]

- Mougi, A.; Kondoh, M. Diversity of Interaction Types and Ecological Community Stability. Science 2012, 337, 349–351. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Navarro, O.; Aguilar-Salinas, B.; Rocha, J.; Olmedo-Álvarez, G. Higher-order interactions and emergent properties of microbial communities: The power of synthetic ecology. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33896. [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.S.; Sørensen, S.J.; Burmølle, M. Bacterial social interactions and the emergence of community-intrinsic properties. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 42, 104–109. [CrossRef]

- Stenuit, B.; Agathos, S.N. Deciphering microbial community robustness through synthetic ecology and molecular systems synecology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 305–317. [CrossRef]

- Román, M.S.; Arrabal, A.; Benitez-Dominguez, B.; Quirós-Rodríguez, I.; Diaz-Colunga, J. Towards synthetic ecology: strategies for the optimization of microbial community functions. Front. Synth. Biol. 2025, 3, 1532846. [CrossRef]

- Brüls, T.; Baumdicker, F.; Smidt, H. Editorial: Synthetic Microbial Ecology. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Escalante, A.E.; Rebolleda-Gã³Mez, M.; Benã tEz, M.; Travisano, M. Ecological perspectives on synthetic biology: insights from microbial population biology. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 143–143. [CrossRef]

- De Roy, K.; Marzorati, M.; Abbeele, P.V.D.; Van de Wiele, T.; Boon, N. Synthetic microbial ecosystems: an exciting tool to understand and apply microbial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 1472–1481. [CrossRef]

- Dunham, M.J. Synthetic ecology: A model system for cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 1741–1742. [CrossRef]

- Timóteo, S.; Albrecht, J.; Rumeu, B.; Norte, A.C.; Traveset, A.; Frost, C.M.; Marchante, E.; López-Núñez, F.A.; Peralta, G.; Memmott, J.; et al. Tripartite networks show that keystone species can multitask. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 37, 274–286. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, K.; Pozo, M.; Tsao, C.-Y.; Hauk, P.; Bentley, W.E. Bacterial co-culture with cell signaling translator and growth controller modules for autonomously regulated culture composition. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fedorec, A.J.H.; Karkaria, B.D.; Sulu, M.; Barnes, C.P. Single strain control of microbial consortia. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Grandel, N. E. et al. Long-term homeostasis in microbial consortia via auxotrophic cross-feeding. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.08.631749 (2025).

- Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Yan, Y.; Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Yuan, Q. Design of stable and self-regulated microbial consortia for chemical synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rousseaux, S.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R.; Sadoudi, M.; Gougeon, R.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Alexandre, H. Wine microbiome: A dynamic world of microbial interactions. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 57, 856–873. [CrossRef]

- Petitgonnet, C.; Klein, G.L.; Roullier-Gall, C.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Vichi, S.; Julien-David, D.; Alexandre, H. Influence of cell-cell contact between L. thermotolerans and S. cerevisiae on yeast interactions and the exo-metabolome. Food Microbiol. 2019, 83, 122–133. [CrossRef]

- Comitini, F.; Agarbati, A.; Canonico, L.; Ciani, M. Yeast Interactions and Molecular Mechanisms in Wine Fermentation: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7754. [CrossRef]

- Novello, V. & de Palma, L. Viticultural strategy to reduce alcohol levels in wine. in Alcohol level reduction in wine (ed. Teissedre, P.-L.) 41–47 (ŒNOVITI INTERNATIONAL Network, 2013).

- Ciani, M.; Morales, P.; Comitini, F.; Tronchoni, J.; Canonico, L.; Curiel, J.A.; Oro, L.; Rodrigues, A.J.; Gonzalez, R. Non-conventional Yeast Species for Lowering Ethanol Content of Wines. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 642–642. [CrossRef]

- Planells-Cárcel, A.; Quintas, G.; Pardo, J.; Garcia-Rios, E.; Guillamón, J.M. Exploring Proteomic and Metabolomic Interactions in a Yeast Consortium Designed to Enhance Bioactive Compounds in Wine Fermentations. Food Front. 2025, 6, 1544–1557. [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, H., Costello, P. J., Remize, F., Guzzo, J. & Guilloux-Benatier, M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae–Oenococcus oeni interactions in wine: current knowledge and perspectives. Int J Food Microbiol 93, 141–154 (2004).

- Balmaseda, A.; Rozès, N.; Bordons, A.; Reguant, C. Molecular adaptation response of Oenococcus oeni in non-Saccharomyces fermented wines: A comparative multi-omics approach. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 362, 109490. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Á.T. A fungal scent from the cheese. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 4524–4526. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Niño, M.; Rodríguez-Cubillos, M.J.; Herrera-Rocha, F.; Anzola, J.M.; Cepeda-Hernández, M.L.; Mejía, J.L.A.; Chica, M.J.; Olarte, H.H.; Rodríguez-López, C.; Calderón, D.; et al. Dissecting industrial fermentations of fine flavour cocoa through metagenomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8638. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Rocha, F.; Cala, M.P.; Mejía, J.L.A.; Rodríguez-López, C.M.; Chica, M.J.; Olarte, H.H.; Fernández-Niño, M.; Barrios, A.F.G. Dissecting fine-flavor cocoa bean fermentation through metabolomics analysis to break down the current metabolic paradigm. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Pitts, E.R.; Budner, D.; Thompson-Witrick, K.A. Kombucha: Biochemical and microbiological impacts on the chemical and flavor profile. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1. [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.; Lee, W.-H.; Eun, J.-B. Metabolite profiling and pathway prediction of laver (Porphyra dentata) kombucha during fermentation at different temperatures. Food Chem. 2022, 397, 133636. [CrossRef]

- Laureys, D.; Britton, S.J.; De Clippeleer, J. Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2020, 78, 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S. A review: chemical, microbiological and nutritional characteristics of kefir. CyTA - J. Food 2014, 13, 340–345. [CrossRef]

- Ströher, J.A.; Oliveira, W.d.C.; de Freitas, A.S.; Salazar, M.M.; Silva, L.d.F.F.d.; Bresciani, L.; Flôres, S.H.; Malheiros, P.d.S. A Global Review of Geographical Diversity of Kefir Microbiome. Fermentation 2025, 11, 150. [CrossRef]

- Prado, M.R.; Blandón, L.M.; Vandenberghe, L.P.S.; Rodrigues, C.; Castro, G.R.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. Milk kefir: composition, microbial cultures, biological activities, and related products. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1177. [CrossRef]

- Louw, N.L.; Lele, K.; Ye, R.; Edwards, C.B.; Wolfe, B.E. Microbiome Assembly in Fermented Foods. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 77, 381–402. [CrossRef]

- Sooresh, M.M.; Willing, B.P.; Bourrie, B.C.T. Opportunities and Challenges of Understanding Community Assembly in Spontaneous Food Fermentation. Foods 2023, 12, 673. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Qiao, M. Towards microbial consortia in fermented foods for metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Food Res. Int. 2025, 201, 115677. [CrossRef]

- Mittermeier, F.; Bäumler, M.; Arulrajah, P.; Lima, J.d.J.G.; Hauke, S.; Stock, A.; Weuster-Botz, D. Artificial microbial consortia for bioproduction processes. Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 23, e2100152. [CrossRef]

- Dippe, M.; Brandt, W.; Rost, H.; Porzel, A.; Schmidt, J.; Wessjohann, L.A. Rationally engineered variants of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthase: reduced product inhibition and synthesis of artificial cofactor homologues. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3637–3640. [CrossRef]

- Wessjohann, L., Bauer, A., Dippe, M., Ley, J. & Geißler, T. Biocatalytic Synthesis of Natural Products by <scp> O </scp> -Methyltransferases. in Applied Biocatalysis: From Fundamental Science to Industrial Applications 121–146 (Wiley, 2016). [CrossRef]

- Remines, M.; Schoonover, M.G.; Knox, Z.; Kenwright, K.; Hoffert, K.M.; Coric, A.; Mead, J.; Ampfer, J.; Seye, S.; Strome, E.D.; et al. Profiling the compendium of changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to mutations that alter availability of the main methyl donor S-Adenosylmethionine. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, S.K.; Avalos, J.L. Harnessing yeast organelles for metabolic engineering. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 823–832. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y. System metabolic engineering modification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase SAM production. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 19. [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, O.S.; Carr, A.V.; Fisher, G.; Hsu, R.H.; Lau, R.; Bowen, B.P.; Hromada, S.; Northen, T.; Arkin, A.P. Deciphering microbial interactions in synthetic human gut microbiome communities. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2018, 14, e8157. [CrossRef]

- Morin, M.A.; Morrison, A.J.; Harms, M.J.; Dutton, R.J. Higher-order interactions shape microbial interactions as microbial community complexity increases. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Qu, Z.; Chen, D.; Wu, H.; Caiyin, Q.; Qiao, J. Deciphering and designing microbial communities by genome-scale metabolic modelling. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 1990–2000. [CrossRef]

- Plata, G.; Srinivasan, K.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Herron, L.; Dixit, P.; Gibbons, J.G. Designing host-associated microbiomes using the consumer/resource model. mSystems 2025, 10, e0106824. [CrossRef]

- Cerk, K.; Ugalde-Salas, P.; Nedjad, C.G.; Lecomte, M.; Muller, C.; Sherman, D.J.; Hildebrand, F.; Labarthe, S.; Frioux, C. Community-scale models of microbiomes: Articulating metabolic modelling and metagenome sequencing. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14396. [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Lu, T. Individual-Based Modeling of Spatial Dynamics of Chemotactic Microbial Populations. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 3714–3723. [CrossRef]

- León, D.S.; Nogales, J. Toward merging bottom–up and top–down model-based designing of synthetic microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 69, 102169. [CrossRef]

- Leggieri, P.A.; Liu, Y.; Hayes, M.; Connors, B.; Seppälä, S.; O'MAlley, M.A.; Venturelli, O.S. Integrating Systems and Synthetic Biology to Understand and Engineer Microbiomes. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 23, 169–201. [CrossRef]

- Jayathilake, P.G.; Gupta, P.; Li, B.; Madsen, C.; Oyebamiji, O.; González-Cabaleiro, R.; Rushton, S.; Bridgens, B.; Swailes, D.; Allen, B.; et al. A mechanistic Individual-based Model of microbial communities. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0181965–e0181965. [CrossRef]

- Hellweger, F.L.; Clegg, R.J.; Clark, J.R.; Plugge, C.M.; Kreft, J.-U. Advancing microbial sciences by individual-based modelling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 461–471. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H.C.; Carlson, R.P. Microbial Consortia Engineering for Cellular Factories: In Vitro to In Silico Systems. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 3, e201210017. [CrossRef]

- Toju, H.; Abe, M.S.; Ishii, C.; Hori, Y.; Fujita, H.; Fukuda, S. Scoring Species for Synthetic Community Design: Network Analyses of Functional Core Microbiomes. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1361. [CrossRef]

- Gonze, D., Coyte, K. Z., Lahti, L. & Faust, K. Microbial communities as dynamical systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 44, 41–49 (2018).

- Joseph, T.A.; Shenhav, L.; Xavier, J.B.; Halperin, E.; Pe’eR, I.; Dakos, V. Compositional Lotka-Volterra describes microbial dynamics in the simplex. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007917. [CrossRef]

- Remien, C.H.; Eckwright, M.J.; Ridenhour, B.J. Structural identifiability of the generalized Lotka–Volterra model for microbiome studies. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q. Building microbial kinetic models for environmental application: A theoretical perspective. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 158. [CrossRef]

- Marschmann, G.L.; Tang, J.; Zhalnina, K.; Karaoz, U.; Cho, H.; Le, B.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Brodie, E.L. Predictions of rhizosphere microbiome dynamics with a genome-informed and trait-based energy budget model. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 421–433. [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, E.; Mehta, P. Geometry of ecological coexistence and niche differentiation. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 108, 044409–044409. [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, M.E.; O’dWyer, J.P. Species dynamics and interactions via metabolically informed consumer-resource models. Theor. Ecol. 2020, 13, 503–518. [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.-Y.; Nguyen, T.H.; Sanchez, J.M.; DeFelice, B.C.; Huang, K.C. Resource competition predicts assembly of gut bacterial communities in vitro. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1036–1048. [CrossRef]

- Pacciani-Mori, L.; Giometto, A.; Suweis, S.; Maritan, A.; Maslov, S. Dynamic metabolic adaptation can promote species coexistence in competitive microbial communities. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007896. [CrossRef]

- Pacciani-Mori, L.; Giometto, A.; Suweis, S.; Maritan, A.; Maslov, S. Dynamic metabolic adaptation can promote species coexistence in competitive microbial communities. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007896. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.; Prats, C.; López, D. Individual-based Modelling: An Essential Tool for Microbiology. J. Biol. Phys. 2008, 34, 19–37. [CrossRef]

- Saula, A. Y., Rowlatt, C. & Bowness, R. Use of Individual-Based Mathematical Modelling to Understand More About Antibiotic Resistance Within-Host. in 93–108 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, R.; Henson, M.A. Genome-Based Modeling and Design of Metabolic Interactions in Microbial Communities. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 3, e201210008. [CrossRef]

- Orth, J. D., Thiele, I. & Palsson, B. Ø. What is flux balance analysis? Nat Biotechnol 28, 245–248 (2010).

- Quinn-Bohmann, N.; Carr, A.V.; Diener, C.; Gibbons, S.M. Moving from genome-scale to community-scale metabolic models for the human gut microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1055–1066. [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, V.R.; Welsh, C.; Diener, C.; Gulliver, E.L.; Rutten, E.L.; Young, R.B.; Giles, E.M.; Gibbons, S.M.; Greening, C.; Forster, S.C. Disease-specific loss of microbial cross-feeding interactions in the human gut. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, F.; Buric, F.; Patil, K.R.; Zelezniak, A. metaGEM: reconstruction of genome scale metabolic models directly from metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, e126–e126. [CrossRef]

- Diener, C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Resendis-Antonio, O.; Chia, N. MICOM: Metagenome-Scale Modeling To Infer Metabolic Interactions in the Gut Microbiota. mSystems 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Borenstein, E. Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 12804–12809. [CrossRef]

- Ravikrishnan, A.; Nasre, M.; Raman, K. Enumerating all possible biosynthetic pathways in metabolic networks. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.D.; Chia, N. Metabolic model-based ecological modeling for probiotic design. eLife 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.; Zimmermann, J.; Baldini, F.; Thiele, I.; Kaleta, C.; Maranas, C.D. BacArena: Individual-based metabolic modeling of heterogeneous microbes in complex communities. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005544. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, R.A.; Olivier, B.G.; Röling, W.F.M.; Teusink, B.; Bruggeman, F.J.; Vera, J. Community Flux Balance Analysis for Microbial Consortia at Balanced Growth. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e64567. [CrossRef]

- Harcombe, W.R.; Riehl, W.J.; Dukovski, I.; Granger, B.R.; Betts, A.; Lang, A.H.; Bonilla, G.; Kar, A.; Leiby, N.; Mehta, P.; et al. Metabolic Resource Allocation in Individual Microbes Determines Ecosystem Interactions and Spatial Dynamics. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 1104–1115. [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, E.A.; Wahl, S.A.; Ishii, S.; Pinto, A.; Ziels, R.; Nielsen, P.H.; McMahon, K.D.; Williams, R.B. Prospects for multi-omics in the microbial ecology of water engineering. Water Res. 2021, 205, 117608. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.M.; Leech, J.; Huttenhower, C.; Delhomme-Nguyen, H.; Crispie, F.; Chervaux, C.; Cotter, P.D. Integrated molecular approaches for fermented food microbiome research. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47. [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, M.; Muth, T. Integrated multi-omics analyses of microbial communities: a review of the current state and future directions. Mol. Omics 2023, 19, 607–623. [CrossRef]

- Mermans, F.; Chatzigiannidou, I.; Teughels, W.; Boon, N.; Newton, R.J. Quantifying synthetic bacterial community composition with flow cytometry: efficacy in mock communities and challenges in co-cultures. mSystems 2025, 10, e0100924. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Sharma, M. Optical biosensors for environmental monitoring: Recent advances and future perspectives in bacterial detection. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116826. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, C.; Cai, X.; Zhang, D.; Guan, G.; Li, B.; Zhang, G. Microbial consortium assembly and functional analysis via isotope labelling and single-cell manipulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degraders. ISME J. 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-P.; Ke, X.; Jin, L.-Q.; Xue, Y.-P.; Zheng, Y.-G. Sustainable management and valorization of biomass wastes using synthetic microbial consortia. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 395, 130391. [CrossRef]

- Troiano, D.T.; Studer, M.H.-P. Microbial consortia for the conversion of biomass into fuels and chemicals. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Patra, D. Synthetic Biology-Enabled Engineering of Probiotics for Precision and Targeted Therapeutic Delivery Applications. Exon 2024, 1, 54–66. [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.K.; Mansell, T.J. Next generation probiotics: Engineering live biotherapeutics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 72, 108336. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wei, L.; Liu, J.; Nielsen, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, N. Relieving metabolic burden to improve robustness and bioproduction by industrial microorganisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 74, 108401. [CrossRef]

- Abdi, G. et al. Scaling Up Nature’s Chemistry: A Guide to Industrial Production of Valuable Metabolites. in Advances in Metabolomics 331–375 (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Meldgin, D.R.; Collins, J.J.; Lu, T. Designing microbial consortia with defined social interactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 821–829. [CrossRef]

- Chigozie, V.U.; Saki, M.; O Esimone, C. Molecular structural arrangement in quorum sensing and bacterial metabolic production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.A.; Jones, O.A.; Beale, D.J.; Boughton, B.A.; Benheim, D.; Kouremenos, K.A.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Wishart, D.S. Current and Future Perspectives on the Structural Identification of Small Molecules in Biological Systems. Metabolites 2016, 6, 46. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.M.; Densmore, D. Hardware, Software, and Wetware Codesign Environment for Synthetic Biology. BioDesign Res. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Lankapalli, A.K.; Mendem, S.K.; Semmler, T.; Ahmed, N.; Rappuoli, R. Unraveling the evolutionary dynamics of toxin-antitoxin systems in diverse genetic lineages of Escherichia coli including the high-risk clonal complexes. mBio 2024, 15, e0302323. [CrossRef]

- Balagaddé, F. K. et al. A synthetic Escherichia coli predator–prey ecosystem. Mol Syst Biol 4, (2008).

- Hong, Y.-J.; Cai, Y.; Antoniewicz, M.R. Cross-feeding of amino acid pathway intermediates is common in co-cultures of auxotrophic Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2025, 88, 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Hanly, T.J.; Urello, M.; Henson, M.A. Dynamic flux balance modeling of S. cerevisiae and E. coli co-cultures for efficient consumption of glucose/xylose mixtures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 93, 2529–2541. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Qiao, K.; Edgar, S.M.; Stephanopoulos, G. Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 377–383. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Yadav, M.; Ghosh, C.; Rathore, J.S. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin modules: classification, functions, and association with persistence. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100047. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, Y.; Yao, J.; Tang, K.; Wang, X. Applications of toxin-antitoxin systems in synthetic biology. Eng. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 100069. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ross, T.D.; Gomez, M.M.; Grant, J.L.; Romero, P.A.; Venturelli, O.S. Investigating the dynamics of microbial consortia in spatially structured environments. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Spaccasassi, A.; Utz, F.; Dunkel, A.; Börner, R.A.; Ye, L.; De Franceschi, F.; Bogicevic, B.; Glabasnia, A.; Hofmann, T.; Dawid, C. Screening of a Microbial Culture Collection: Empowering Selection of Starters for Enhanced Sensory Attributes of Pea-Protein-Based Beverages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15890–15905. [CrossRef]

- de Ullivarri, M.F.; Merín, M.G.; Raya, R.R.; de Ambrosini, V.I.M.; Mendoza, L.M. Killer yeasts used as starter cultures to modulate the behavior of potential spoilage non-Saccharomyces yeasts during Malbec wine fermentation. Food Biosci. 2023, 57. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B., Riley, M. A., Feldman, M. W. & Bohannan, B. J. M. Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock–paper–scissors. Nature 418, 171–174 (2002).

- Liao, M.J.; Miano, A.; Nguyen, C.B.; Chao, L.; Hasty, J. Survival of the weakest in non-transitive asymmetric interactions among strains of E. coli. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Zhuang, W.; Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Song, A.; et al. Construction of a synthetic microbial community based on multiomics linkage technology and analysis of the mechanism of lignocellulose degradation. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 389, 129799. [CrossRef]

- Sui, M., Rong, J., Zhang, Y., Xie, H. & Zhang, C. Screening of Cellulose Degrading Bacteria and Construction of Complex Microflora. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 632, 032021 (2021). [CrossRef]

| Design principle | Challenges | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback circuits regulate predator–prey oscillations and prevent collapse | Population crashes; partner dominance | Predator–prey E. coli with toxin–antitoxin kill switches [185,186] |

| Mutualism and division of labor enforce metabolic interdependence and reduce competition | Escape mutants; social cheaters | E. coli–S. cerevisiae acetate cross-feeding; amino acid auxotrophies [187,188,189] |

| Competitive balance via negative feedback avoids exclusion and stabilizes coexistence | Ecological drift; unintended dominance | Synthetic bacteriocin modules; programmed toxin–antitoxin systems[190,191] |

| Spatial partitioning and niche specialization buffer direct competition and enhance robustness | Loss of redundancy; stochastic fluctuations | Microfluidic consortia; structured starter cultures in wine/cheese [192,193,194] |

| Higher-order motifs (e.g. rock–paper–scissors) promote coexistence and emergent stability | Context dependence; collapse under fluctuation. | Non-transitive E. coli consortia [195,196] |

| Functional redundancy distributes key tasks across partners, increasing resilience | Keystone loss; cascading failures | Multi-strain cellulose degradation; trait-based lignocellulose consortia [197,198] |

| Domain | Current challenge | Gap / limitation | Bullet points |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Microbial communication (language) |

Crosstalk Environmental noise Undermine orthogonality |

Signal instability; lack of insulated channels | Expand chemical space (engineered autoinducers, peptide libraries, bioprospecting); standardize orthogonal systems; implement real-time monitoring |

|

Temporal synchronization (rhythm) |

Oscillators drift under fluctuations and scale-up | No robust frameworks for multi-signal coupling | Engineer noise-resistant, feedback-stabilized oscillators; embedded within ecological contexts |

|

Ecological stability (harmony) |

Evolutionary escape, cheaters, shifting keystones | Fragile reliance on keystones; limited redundancy | Design adaptive scaffolds; incorporate redundancy and distributed resilience; monitor higher-order motifs dynamically |

|

Modelling integration (conductor) |

Fragmented tools (GEMsa, CRMsb, IBMsc) rarely connected | No unified platform across genetic–ecological–process scales | Develop hybrid frameworks; create dedicated software; link directly to design–build–test–learn cycles |

|

Process-scale translation (bridge) |

Scale-up introduces heterogeneity, mixing and oxygen limits | Few validated lab-to-industry workflows | Couple bioprocess engineering with synthetic design from the outset; establish microfluidics-to-fermenter pipelines |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).