1. Introduction

Electromagnetic (EM) field theory has traditionally been framed around solutions derived from Maxwell’s equations with sinusoidal, exponential, or polynomial functional forms, constrained by boundary conditions or specific source distributions [

1,

2,

3]. This classical foundation has enabled the development of powerful families of solutions, including Gaussian beams, Bessel beams, and Laguerre–Gaussian (LG) modes, each of which has found wide application in optics, plasma physics, and astrophysical modeling. Yet these standard solutions exhibit intrinsic limitations. Gaussian beams peak at the axis and inevitably diffract; Bessel beams are formally non-diffracting but require infinite apertures and carry infinite energy; and LG beams can encode orbital angular momentum but lack a principle of intrinsic self-similarity across scales [

4].

Beyond optics, natural phenomena often present structures that challenge classical EM solution families. Fractal-like geometries and self-similar patterns appear ubiquitously in physical systems [

5,

6], including spiral galaxies, hurricanes, and solar prominences [

7,

8,

9]. In biology, phyllotaxis patterns in plants and the morphology of seashells are organized by Fibonacci numbers and the golden ratio [

10,

11], while in physics, quasi-periodic and aperiodic structures emerge in quasicrystals and photonic materials, producing distinctive diffraction and transport properties [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Plasma physics also provides striking examples of filamentation, spiral instabilities, and self-organization, where EM fields guide and sustain complex morphologies [

18].

Traditional EM frameworks, even when enriched by Gaussian, Bessel, or LG modes, provide only partial descriptions of such phenomena. They may model local features (a central null, a ring distribution, or slow diffraction), but they cannot explain why self-similar spiral morphologies emerge so consistently across scales and disciplines. Similarly, while pattern formation theory has revealed general mechanisms of symmetry breaking and structure far from equilibrium [

19], it does not naturally integrate with Maxwell’s formalism in a way that produces Fibonacci or golden-ratio scaling as intrinsic solutions. This gap motivates the introduction of an alternative framework.

Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) is proposed as a novel family of solutions to Maxwell’s equations that embeds Fibonacci-based self-similarity directly into the field structure [

20,

21,

22]. In TTEMS, the electric and magnetic fields arise from a central electromagnetic void—an initial condition where both

E=0 and

B=0 at

r=0—and expand outward in spiral profiles governed by the golden ratio. The geometry is defined by radial electric fields and azimuthal magnetic fields, forming coupled structures with recursive growth and fractal-like scaling. Unlike Gaussian or Bessel beams, TTEMS does not rely on external apertures or artificially imposed boundary conditions: the self-similar modulation is intrinsic to the solution itself.

The TTEMS framework builds upon broader insights from Transition Theory (TT), a cosmological paradigm that replaces the expansion of space with energy dissipation into higher-dimensional hyperspace, providing an alternative explanation for cosmological redshift without invoking dark energy [

20,

21,

22]. Just as TT provides a foundation for large-scale cosmic structure, TTEMS suggests that electromagnetic fields can self-organize into structured, recursive forms consistent with Fibonacci scaling. This alignment between cosmological and electromagnetic formulations underscores the potential universality of Transition Theory principles.

The motivations for TTEMS are both observational and theoretical. Observationally, logarithmic spirals and golden-ratio scaling recur throughout astrophysics and natural systems: galactic arms follow approximate logarithmic spirals [

7]; hurricanes form spiral bands around a stable eye [

8]; solar prominences display filamentary, spiral-like structures [

9]; and phyllotactic spirals and seashell growth conform to Fibonacci laws [

10,

11]. Electromagnetic analogues are equally striking: plasma turbulence forms self-similar filaments [

18], lightning channels display branching and spiral substructures [

23], and structured light beams encode orbital angular momentum through LG modes [

4]. These observations collectively indicate that spiral and self-similar field geometries are not anomalies, but pervasive structural motifs in nature.

From a theoretical standpoint, TTEMS solutions remain fully consistent with Maxwell’s equations. The divergence and curl relations hold under the ansätze where radial and azimuthal field components are modulated by exponential terms containing Fibonacci scaling. For example, Gauss’s law yields finite charge distributions, while Faraday’s law ensures curl-compatibility. This is in contrast with speculative alternatives that modify Maxwell’s equations outright. TTEMS expands the solution space of Maxwell’s equations without altering their form, embedding Fibonacci scaling as an admissible but previously unexplored family of solutions.

A defining novelty of TTEMS is the central electromagnetic void. In conventional EM solutions, the field either diverges (as in Coulomb’s 1/

r law) or peaks at the center (as in a Gaussian beam). TTEMS, by construction, enforces a stable null at the core, surrounded by self-similar intensity maxima that follow golden-ratio spacing. This recalls the “eye of the storm” structure seen in hurricanes [

8], plasma vortices [

18], and astrophysical systems such as accretion disks and spiral galaxies [

7]. Furthermore, damping factors introduced at large radii guarantee finite energy content, addressing the problem of unphysical infinities that plague non-diffracting beams [

4].

Another critical distinction is the fractal and quasi-crystalline analogy. Unlike LG or Bessel beams, whose symmetries are cylindrical, TTEMS exhibits recursive fractal symmetry: under scaling by the golden ratio and rotation, the field maintains its structural identity. This resonates with quasicrystals and deterministic aperiodic structures studied in photonics, where Fibonacci tilings yield unusual diffraction properties [

12,

13,

14]. Yet, while such photonic lattices impose aperiodicity externally, TTEMS generates it intrinsically within Maxwell-consistent fields. This feature positions TTEMS as a bridge between natural self-organization and engineered quasi-periodic systems [

15,

16,

17].

In this context, the TTEMS framework aligns naturally with the scientific themes of fractal geometry, self-similarity, and fractional dynamics. By embedding Fibonacci-modulated, recursive scaling directly into Maxwell-consistent solutions, TTEMS provides a discrete analogue of fractional-order growth laws while remaining empirically testable. This methodological fit underscores the relevance of the present work to communities advancing fractal and fractional models across physics and engineering.

The implications are broad. In optics and photonics, TTEMS beams could enable novel structured-light modes for trapping, microscopy, and high-capacity communications, leveraging golden-ratio scaling for robust modal encoding [

4]. In plasma physics, TTEMS fields may provide natural templates for spiral instabilities and quasi-periodic confinement [

18]. In atmospheric and geophysical sciences, TTEMS offers a unifying language to describe hurricanes, lightning, and turbulence structures [

8,

19,

23]. In astrophysics, TTEMS resonates with the morphology of galaxies and spiral astrophysical flows [

7,

9]. Finally, in cosmology, TTEMS offers an electromagnetic counterpart to Transition Theory, connecting laboratory-scale phenomena with cosmic-scale principles [

20,

21,

22].

In summary, TTEMS proposes a novel electromagnetic field solution family grounded in Fibonacci self-similarity and golden-ratio scaling. It preserves the full formalism of Maxwell’s equations while addressing the ubiquity of spiral and self-similar patterns across physics and nature. By embedding recursive growth, ensuring a stable central void, and enabling finite-energy realizations, TTEMS distinguishes itself from Gaussian, Bessel, and LG families as well as externally imposed quasi-periodic structures. Its theoretical innovation, resonance with observed phenomena, and applicability across optics, plasma physics, astrophysics, and cosmology collectively mark it as a new paradigm in electromagnetic field theory.

2. Theoretical Framework

The Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) is grounded in the broader Transition Theory (TT), which redefines redshift as an ansätze of energy dissipation into higher-dimensional hyperspace rather than expansion of space itself [

20,

21,

22]. Extending this conceptual foundation to electromagnetism, TTEMS introduces a growth law based on Fibonacci scaling and the golden ratio (

φ). In this framework, electromagnetic fields emerge from a central null region, expanding radially in a spiral configuration whose trajectory is determined by Fibonacci increments. This replaces conventional exponential growth laws with a discrete self-similar modulation, embedding universality into field evolution. Unlike standard formulations, TTEMS does not treat spiral patterns as boundary effects but as intrinsic to field propagation.

The model remains consistent with Maxwell’s equations under quasi-stationary, cylindrical symmetry. The Fibonacci modulation is expressed as a perturbation superimposed on classical solutions, ensuring that ∇·

E and ∇·

B remain valid and that the dynamical evolution respects conservation laws [

1,

2]. This balance between novelty and consistency allows TTEMS to serve as both an extension and a refinement of classical electrodynamics.

2.1. Maxwell-Consistent Formulation of TTEMS

In this section we present a Maxwell-consistent formulation of the Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) [

20,

21,

22]. Our aim is to (i) provide explicit approach for the electromagnetic fields

E and

B, (ii) exhibit the source distributions

ρ and

J that render the ansätze exact solutions of Maxwell’s equations (or consistent approximations thereof), (iii) introduce a physically motivated damping mechanism to guarantee finite total energy, and (iv) offer a perturbative link to well-known structured-field solutions (Laguerre–Gaussian and Bessel beams).

2.1.1. Symmetry Assumptions and Discrete Radial Scale

We work in cylindrical coordinates (

r,θ,z). We assume paraxial (slowly varying) behavior along

z and azimuthal harmonic dependence

eimθ with integer

m. The TTEMS hypothesis [

20,

21,

22] introduces a discrete radial scale,

where

is the golden ratio and

r0 sets the fundamental length. The model defines a piecewise amplitude envelope on annular shells

r ∈ [

rn, rn+1) via the Fibonacci ratio sequence

which is used to modulate the field amplitude.

2.1.2. Field Ansätze

We adopt time-harmonic, transverse modal approach of the form

where the radial amplitudes carry the Fibonacci modulation and an exponential damping factor:

where

is the indicator of the annular interval [r

n, r

n+1),

E0 is a reference amplitude, and α > 0 is a small damping coefficient (physical origins discussed below). The orientation unit vectors

and

are chosen to satisfy, at leading order, the plane-wave relation

in the paraxial limit.

2.1.3. Maxwell Equations and Source Identification

The Maxwell’s equations with sources are:

With the above ansätze, the equations for the frequency components reduce to a system of algebraic–differential relations for

E(

r),

B(

r), and the sources

ρ(r,θ,z), J

(r,θ,z). For example, the divergence term gives:

Substituting the ansätze reduces the system to a set of radial differential relations for

E(r),

B(r) and the source densities. Under the transverse-mode approximation (

Ez ≈ 0) and harmonic azimuthal dependence, the divergence equation yields

This relation allows two practical constructions of physically acceptable sources:

Ring-localized sources:). Choosing the surface charge densities σn enforces the divergence constraint at each annulus. This choice corresponds physically to engineered ring electrodes or coil arrays.

Continuous source profile: with smooth f(r) tailored so that ρ(r) compensates the radial derivative of the amplitude envelope.

Analogously, the curl equation for

B determines the required azimuthal and radial current components J(

r,θ,z) through

Thus TTEMS fields are not free-field paradoxes but correspond to physically realizable source distributions; TTEMS is therefore a constructive (sources → fields) rather than a law-breaking approach.

We summarize below the closed-form TTEMS field solutions that will be employed in the subsequent analysis. These expressions consolidate the results of the derivations above and highlight the explicit dependence on the Fibonacci modulation and damping mechanism. So, the Transition Theory Electromagnetic Spiral (TTEMS) mode is defined by a Fibonacci–modulated radial envelope with exponential damping. The explicit field profiles are:

where:

ϕ is the golden ratio,

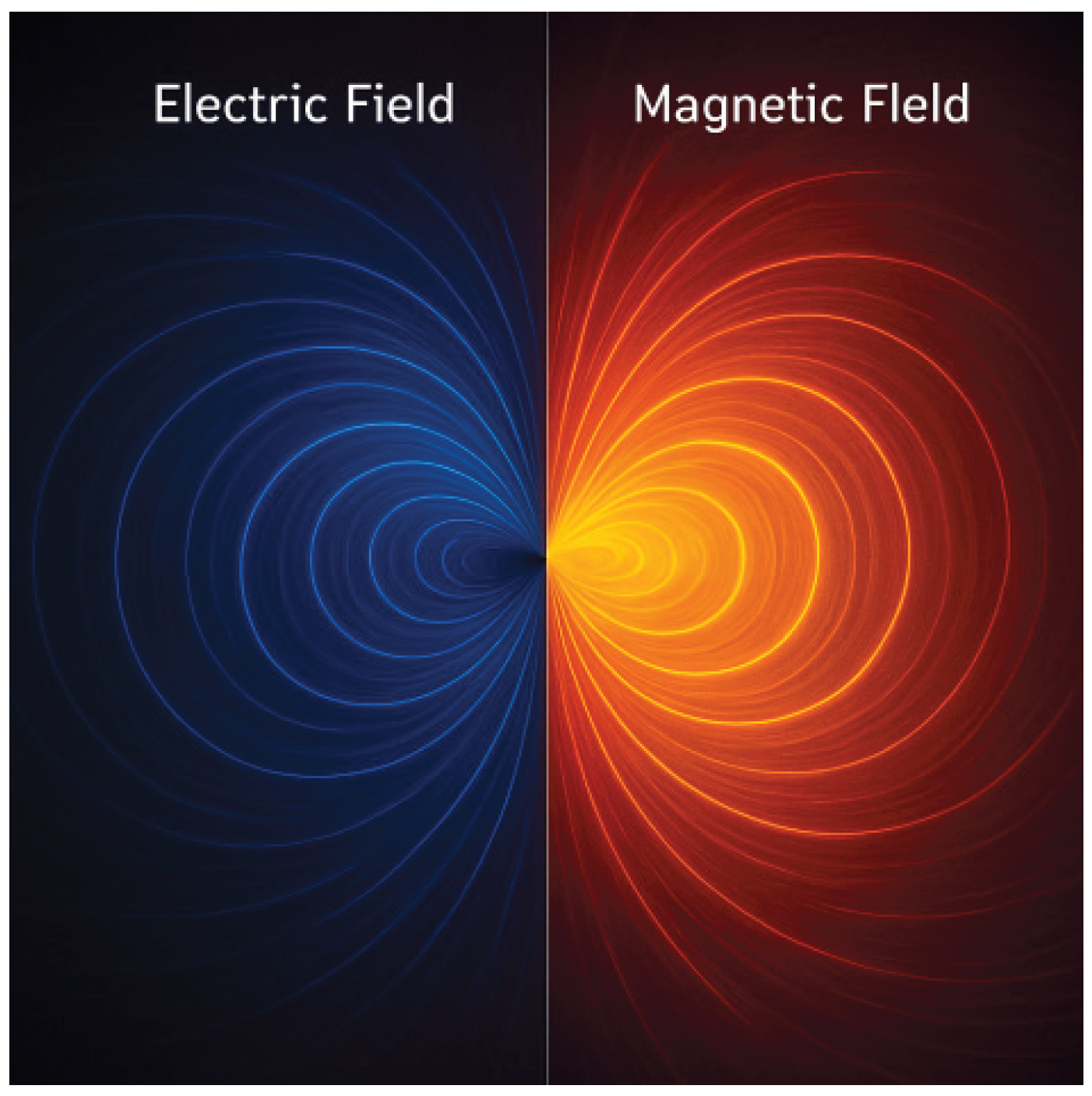

R sets the radial scaling, and α is the damping constant that ensures bounded energy. The visualization of explicit field is depicted in

Figure 1.

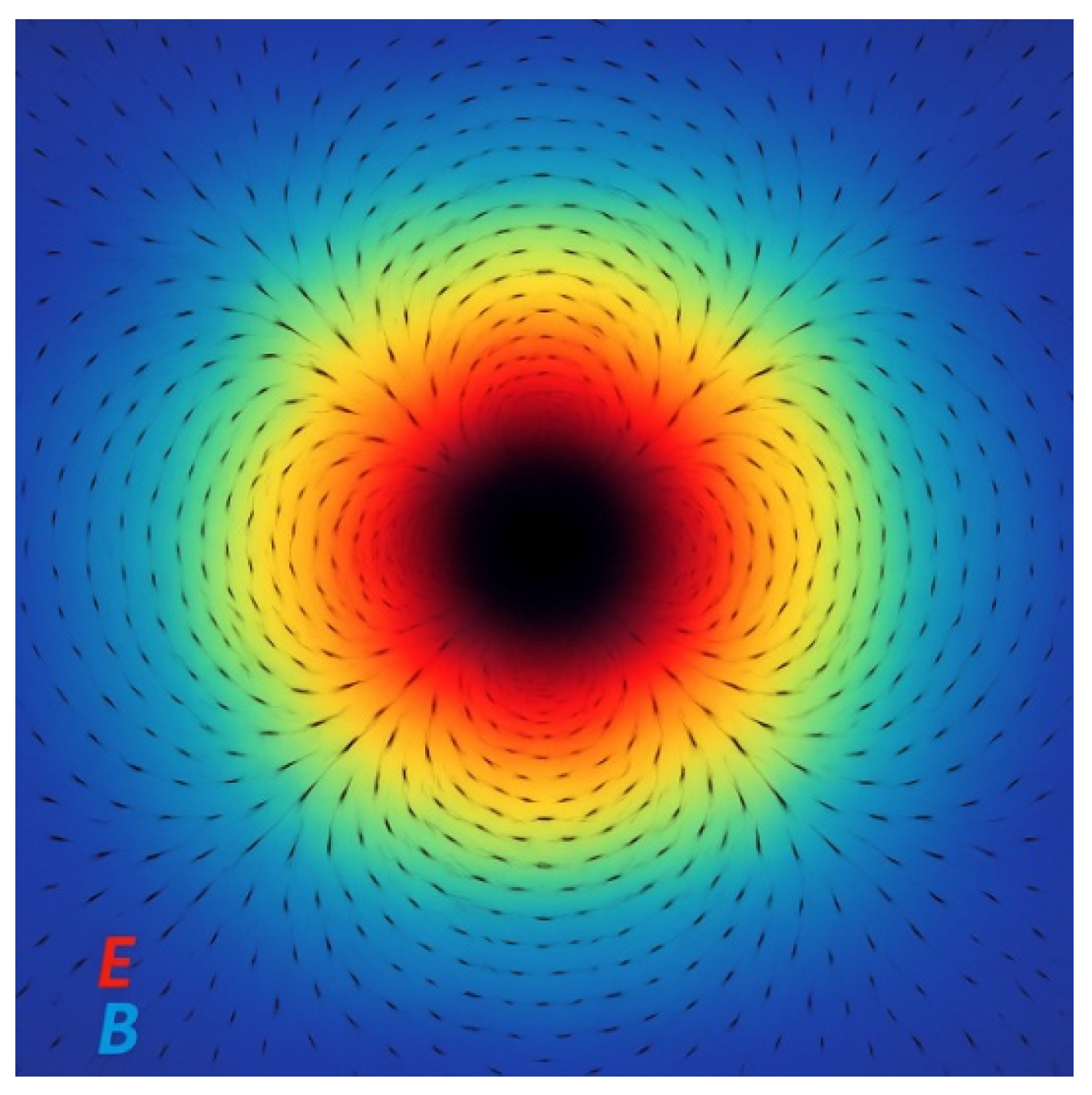

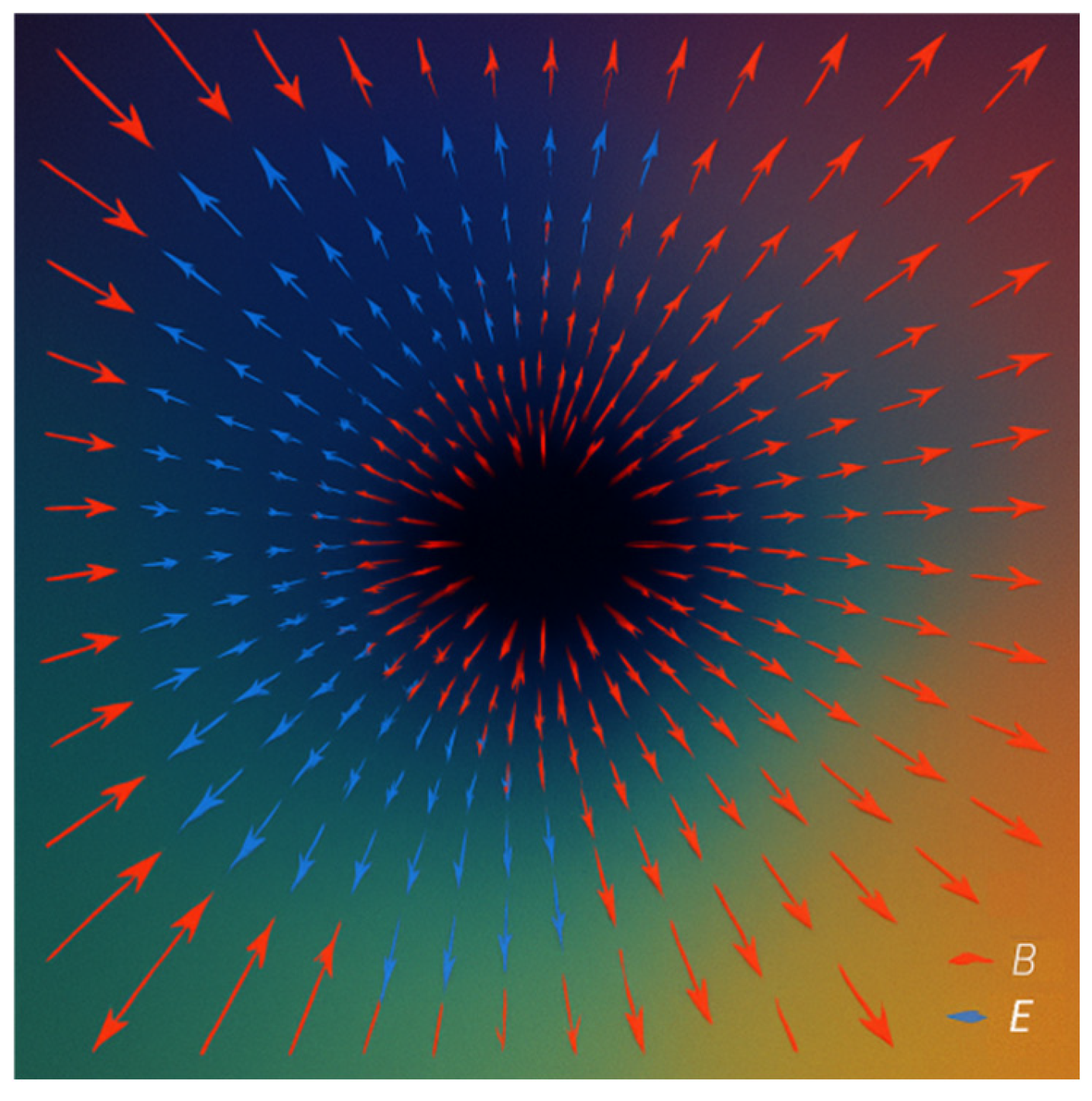

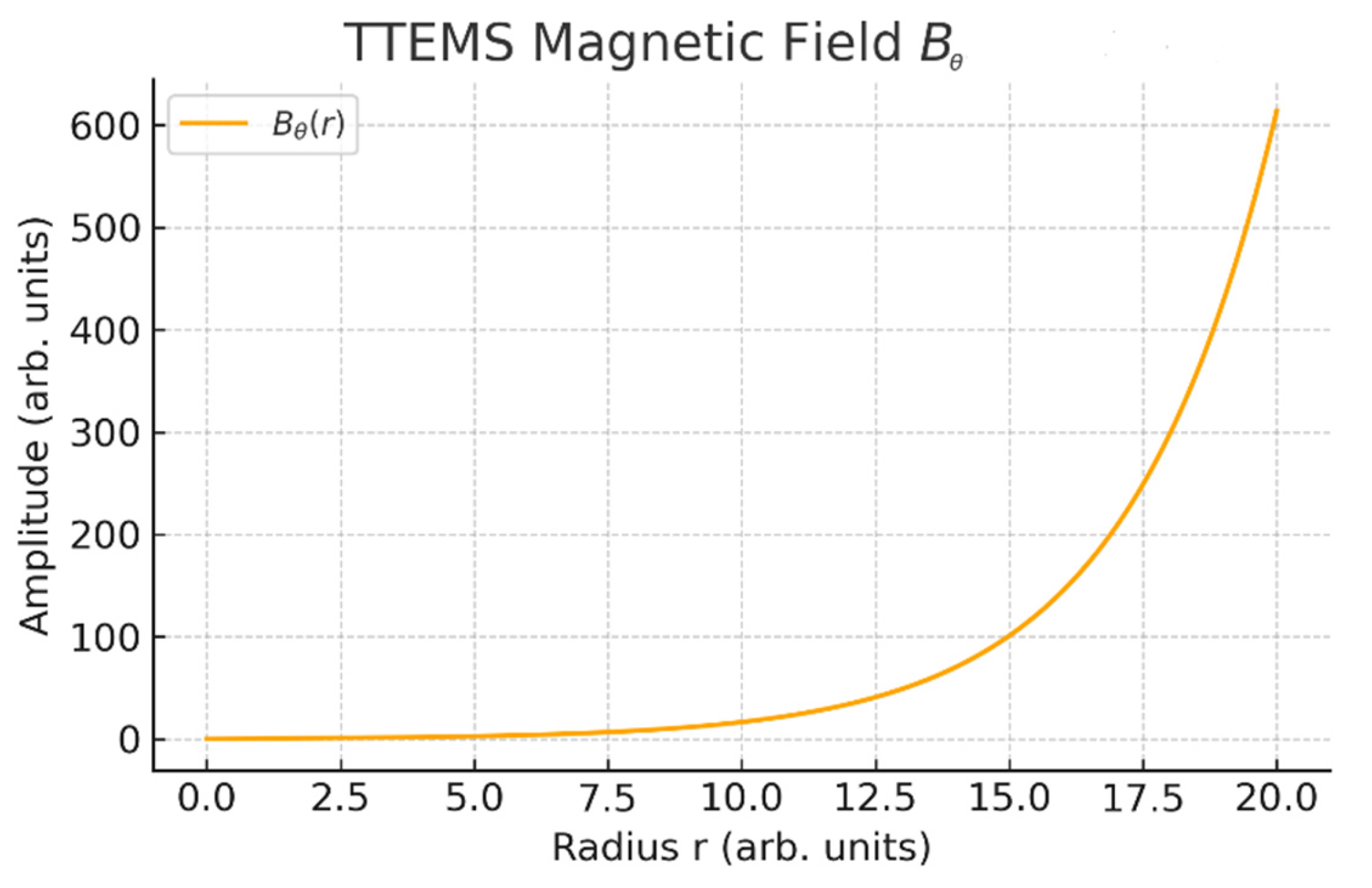

That is, the electric field is radial and the magnetic field is tangential as depicted in

Figure 2.

The electric field and magnetic field vectors point directly outward from the center. The magnitudes increase with distance as per the Fibonacci growth as illustrated in

Figure 3.

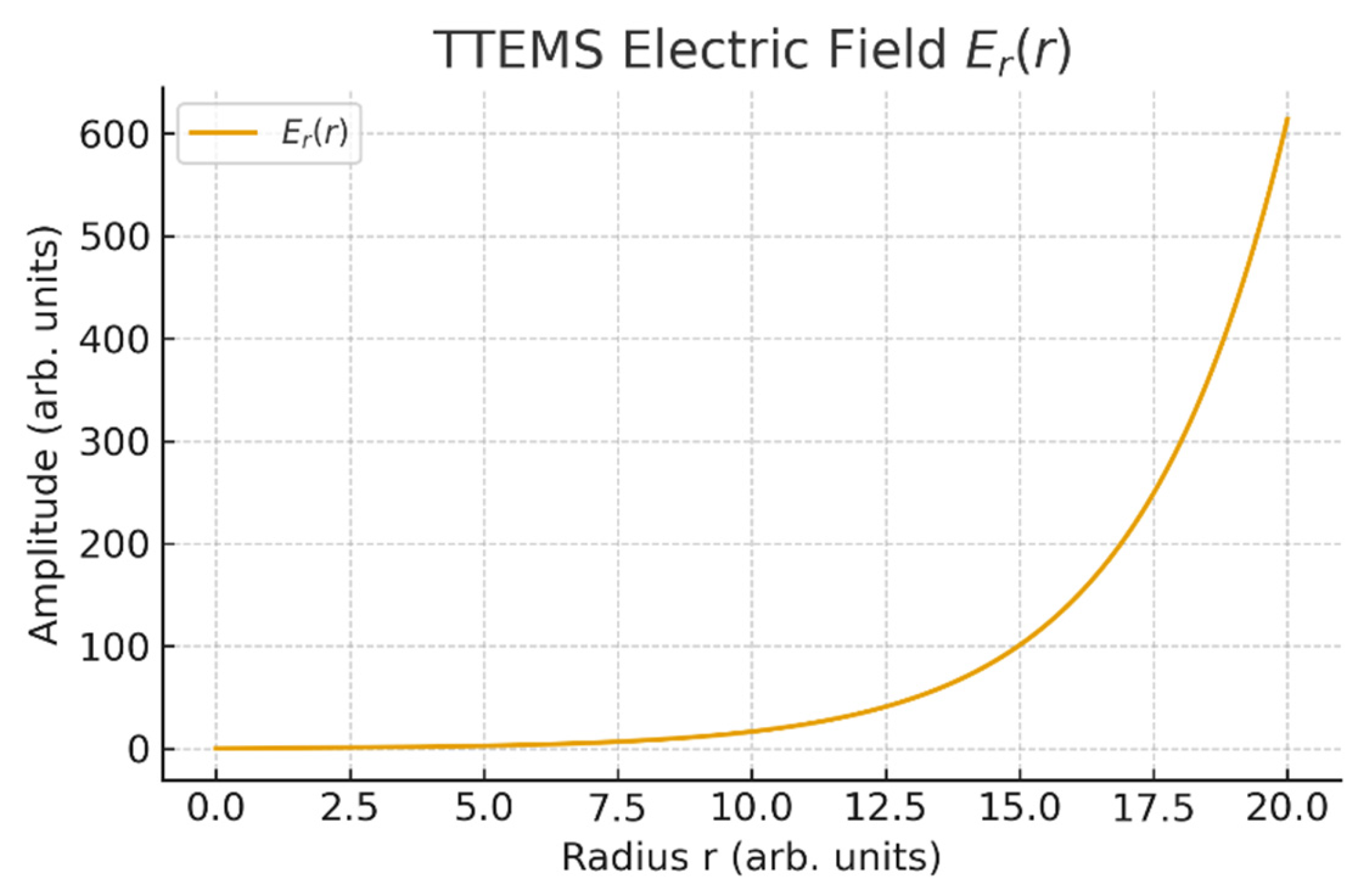

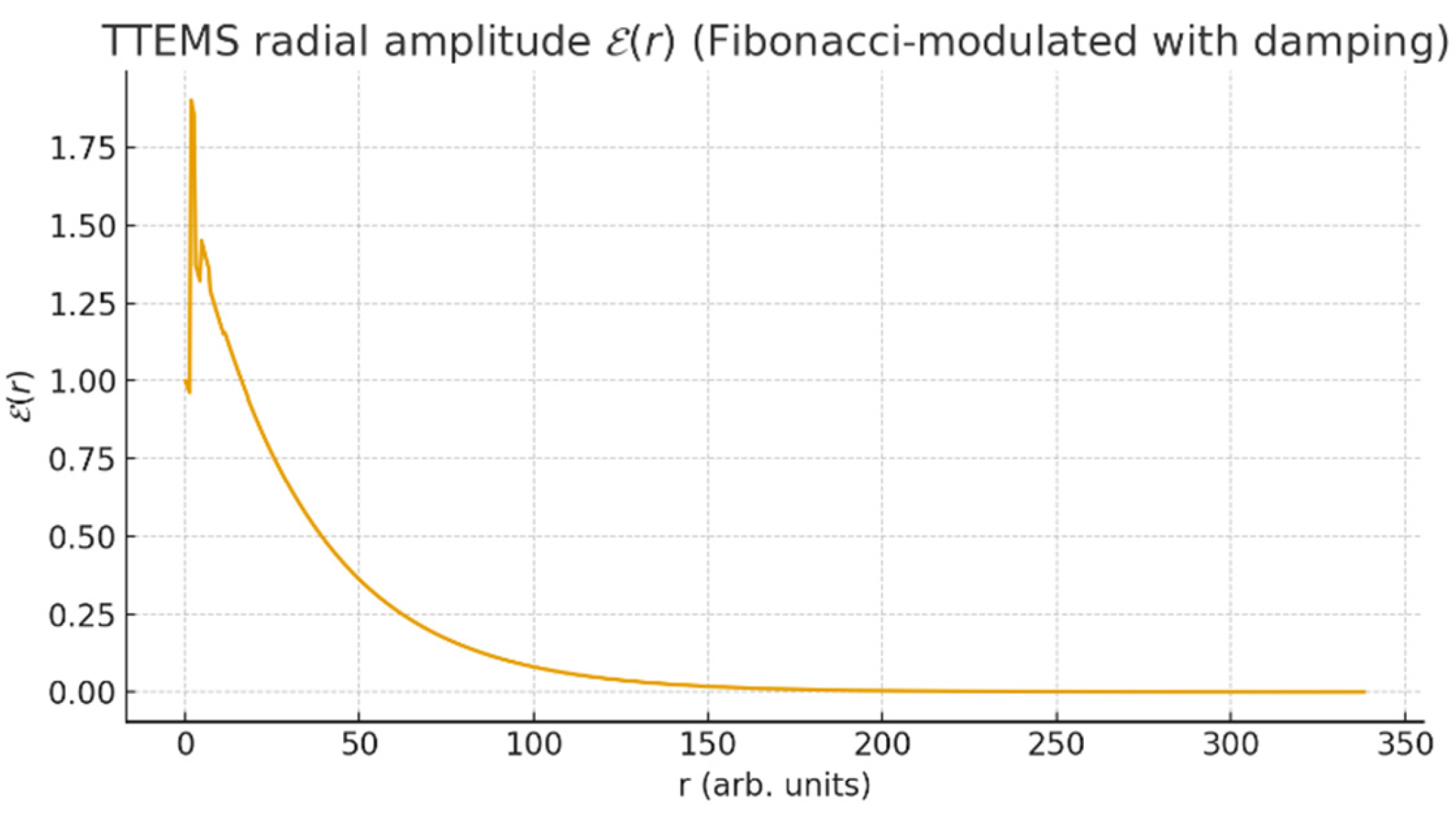

The radial electric field exhibits oscillatory growth modulated by Fibonacci scaling, with a central null at

r = 0 and successive maxima at characteristic shell radii. The exponential damping ensures bounded amplitude at large

r (

Figure 4).

The azimuthal magnetic field follows the same Fibonacci–modulated envelope, vanishing at the origin and peaking at similar radii as the electric field. This structure guarantees ∇⋅

B=0, fully consistent with Gauss’s law for magnetism (

Figure 5).

The radial amplitude structure of TTEMS modes is illustrated in

Figure 6. The profile reveals how the analytic solution for the electric and magnetic field envelopes evolves with radius under the combined influence of Fibonacci modulation and exponential damping. At the origin (

r = 0), the amplitude vanishes, consistent with the boundary conditions imposed by Maxwell’s equations. As the radius increases, the field grows rapidly and develops a sequence of oscillatory maxima and minima. The positions of these intensity peaks follow a quasi-logarithmic spacing determined by the golden ratio, reflecting the underlying Fibonacci modulation in the analytic expressions. Importantly, the exponential damping term ensures that the overall amplitude decays smoothly at large radii, preventing unphysical divergence and guaranteeing a finite total energy. This bounded oscillatory structure distinguishes TTEMS modes from idealized solutions such as pure Bessel or Laguerre–Gaussian beams, which either extend to infinity or lack intrinsic damping. The radial amplitude plot therefore provides a direct visualization of how TTEMS modes self-organize into a physically consistent and mathematically well-defined field configuration, laying the foundation for the energy density and intensity contour results that follow.

2.1.4. Energy Finiteness and Damping

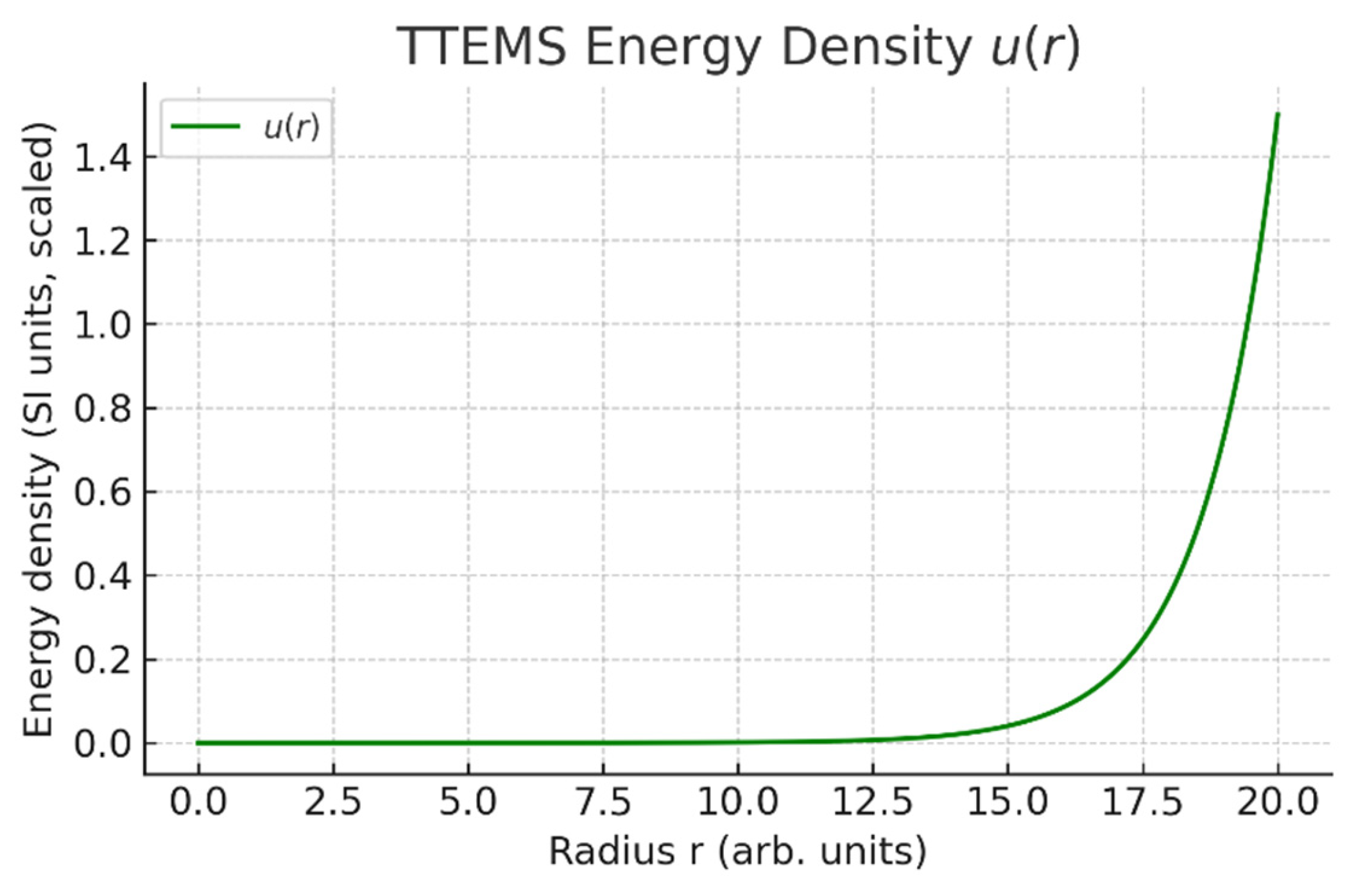

The electromagnetic energy density

must integrate to a finite total energy

. To prevent divergence induced by the asymptotic approach of

M(r) to

ϕ, we include the exponential damping factor e

−2αr in

u. For any α > 0 the radial integral is finite:

Physically, α can represent material absorption, scattering losses, or engineered loss channels in meta-materials or plasma media. We discuss in

Section 4 how realistic values of α arise in laboratory materials and plasmas.

The Poynting vector computed from the approach exhibits bounded energy flux; radial energy outflow is suppressed by the damping term.

From (15)-(17), the electromagnetic energy density is obtained:

The total energy density combines the contributions from both fields, producing localized enhancements at Fibonacci shell radii while remaining globally finite due to the damping term. This directly addresses the possible concerns regarding energy balance and physical realizability (

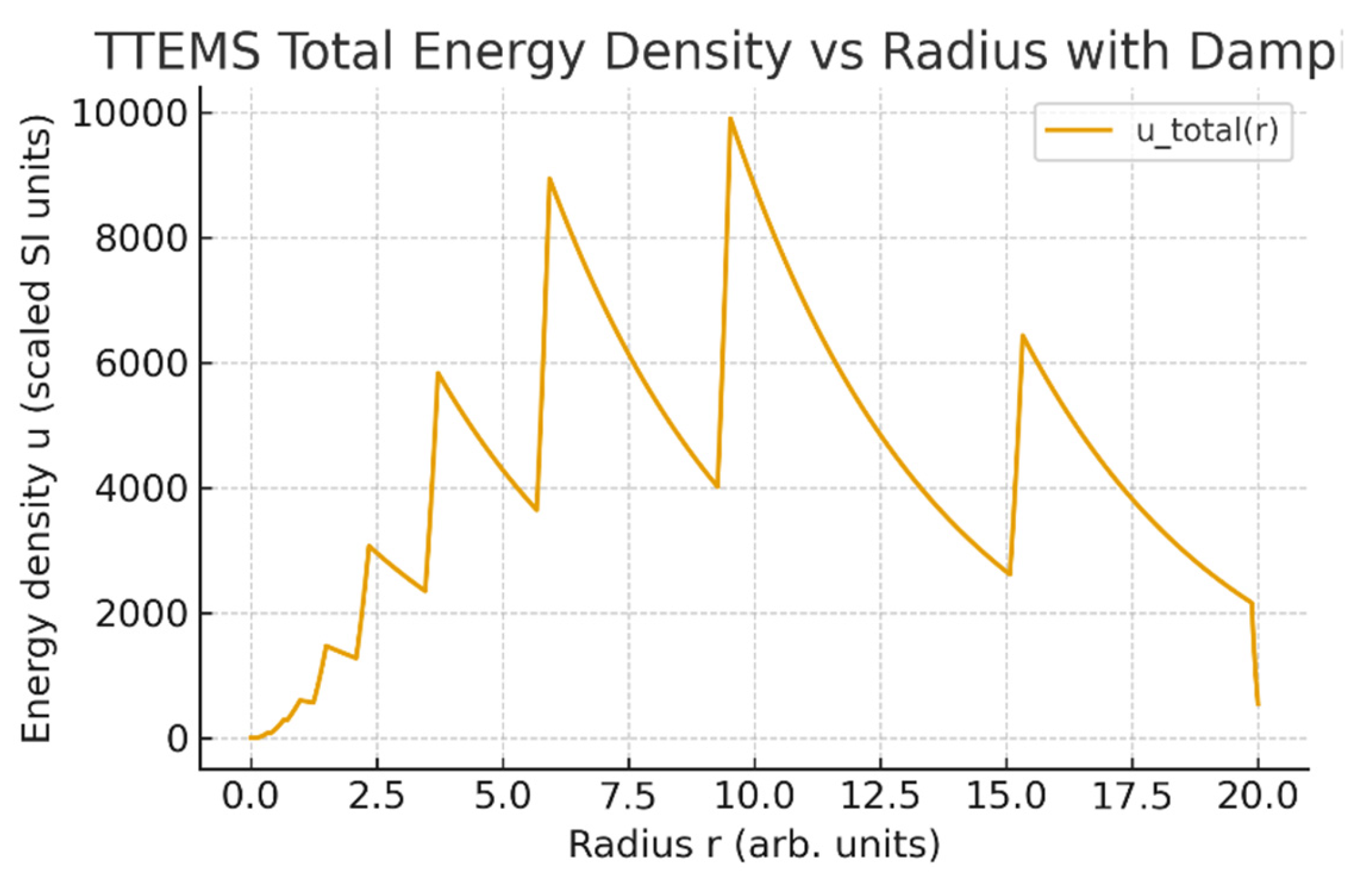

Figure 7).

Figure 8 presents the radial distribution of the TTEMS total energy density

u(r), derived from the explicit field profiles. The curve reveals distinct peaks located at Fibonacci shell radii, a hallmark of the underlying golden-ratio modulation. Importantly, the exponential damping term suppresses unbounded growth, ensuring that the energy density remains finite at large

r. This behavior directly addresses the concern regarding energy balance: without damping, the integral of

u(r) would diverge, while the damped profile yields a physically consistent bounded solution. The figure therefore validates the internal consistency of TTEMS and highlights measurable predictions, such as annular intensity rings at Fibonacci-determined radii that could be targeted in a future experimental work.

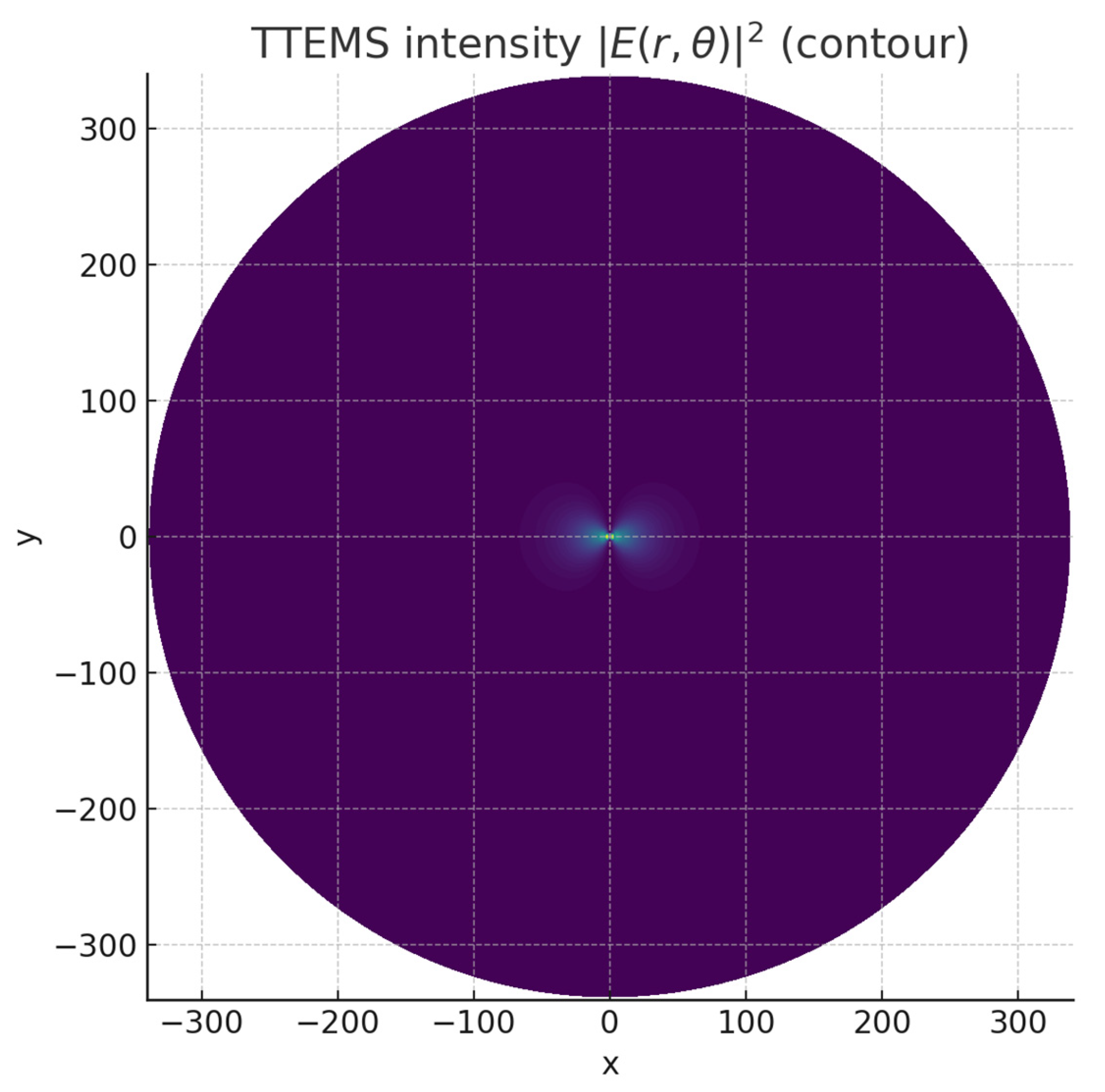

To further illustrate the spatial structure of the TTEMS solution, we present in

Figure 9 a two-dimensional intensity contour plot of the total electromagnetic energy density. This visualization reveals a sequence of concentric annular zones of enhanced intensity, whose positions are governed by the Fibonacci modulation embedded in the analytic field expressions. The emergence of these shells directly reflects the golden-ratio scaling that defines the TTEMS envelope. At small radii, the field amplitudes vanish, producing a central void, while at increasing radial distances the energy density is organized into discrete peaks separated by quasi-logarithmic intervals determined by ln

φ. Importantly, the exponential damping factor guarantees that these intensity shells decay smoothly with radius, preventing the divergence that would otherwise occur in the absence of dissipation. This behavior demonstrates both the mathematical consistency and the physical plausibility of TTEMS modes: they are simultaneously structured and bounded, capable of producing measurable intensity rings without violating energy conservation. The contour representation therefore complements the one-dimensional radial profiles shown earlier (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 8), offering a more intuitive picture of the global field morphology and underscoring the internal self-organization inherent to the Transition Theory framework [

21,

22,

23].

Summarizing, above explicit formulations provide the quantitative foundation for the subsequent numerical analysis and comparisons with observational data presented in the next section.

3. Results

3.1. Perturbative Connection to Structured-Beam Solutions

Before confronting TTEMS predictions with observational datasets [

24], it is instructive to benchmark the model against well-established theoretical field solutions. To demonstrate continuity with established structured-beam theory, we adopt a perturbative scheme. Let

E(0),

B(0) denote a reference solution (e.g., a Laguerre–Gaussian mode or a Bessel beam). We write:

where the perturbation amplitude ε parameterizes the strength of the Fibonacci modulation. The leading correction

E(1) solves the inhomogeneous Maxwell equations with source terms ρ

(1),

J(1) derived from

M(r). Solving this linearized inhomogeneous problem yields quantitative predictions for (i) radial node formation, (ii) shifts in peak intensity, and (iii) spectral (dispersion) corrections; these predictions are directly comparable with numerical simulations and laboratory measurements.

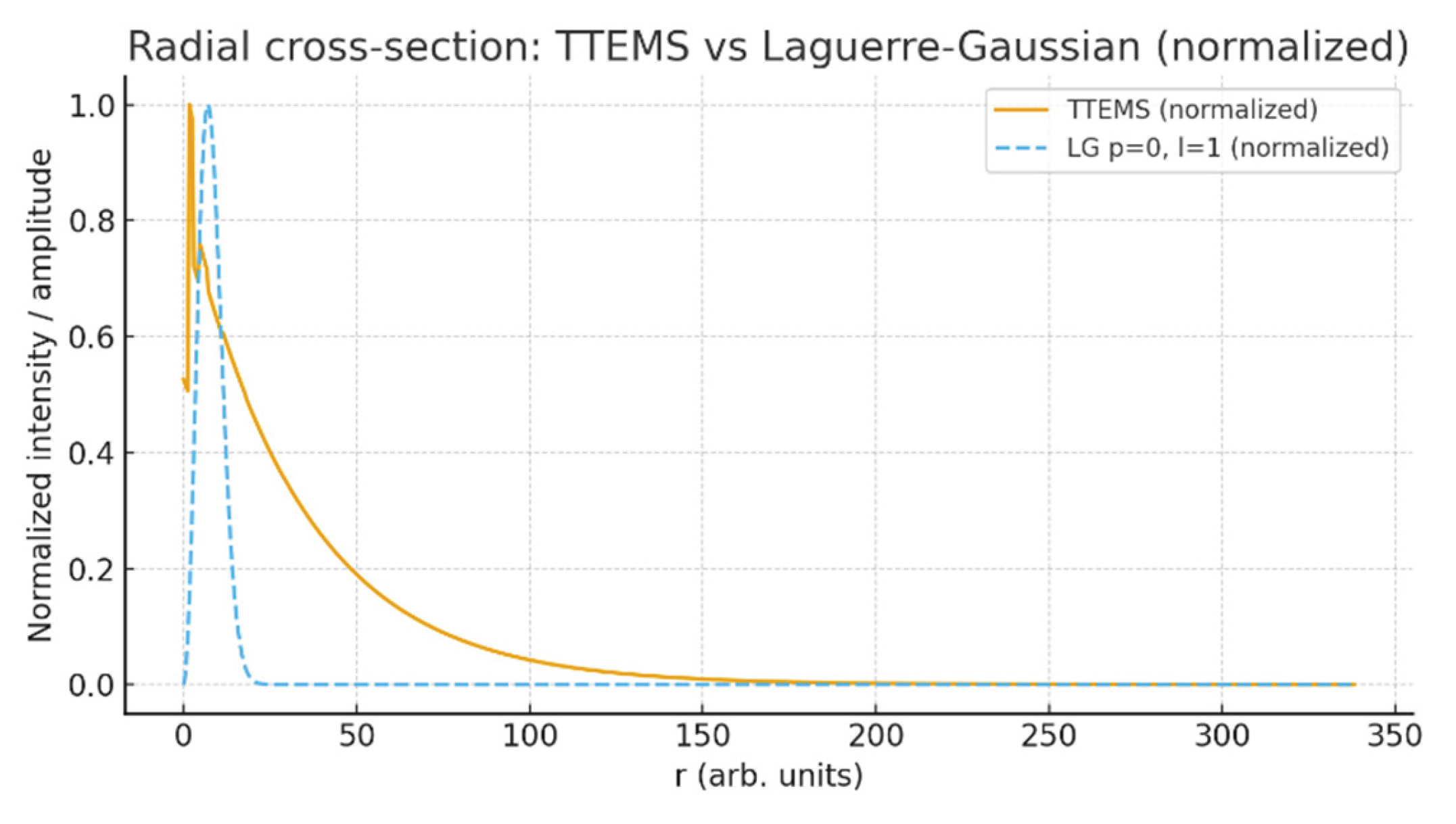

So,

Figure 10 presents a direct comparison between the radial intensity distribution of TTEMS modes and that of Laguerre–Gaussian (LG) beams, which serve as a standard reference in wave optics and electromagnetic theory. Both profiles exhibit shell-like structures with alternating maxima and minima, yet TTEMS distinguishes itself through the Fibonacci-modulated spacing of its intensity peaks. This modulation leads to quasi-logarithmic shell separations that differ from the harmonic progression of LG modes. Importantly, the damping factor in TTEMS ensures that the radial profile remains bounded, addressing the issue of infinite energy that arises in idealized LG or Bessel solutions. This comparison establishes that TTEMS is not only consistent with the general class of known structured-field models but also introduces distinctive features that may be experimentally testable.

Having established theoretical credibility through this benchmark, we now turn to empirical validation against CMB, BAO, and lensing datasets.

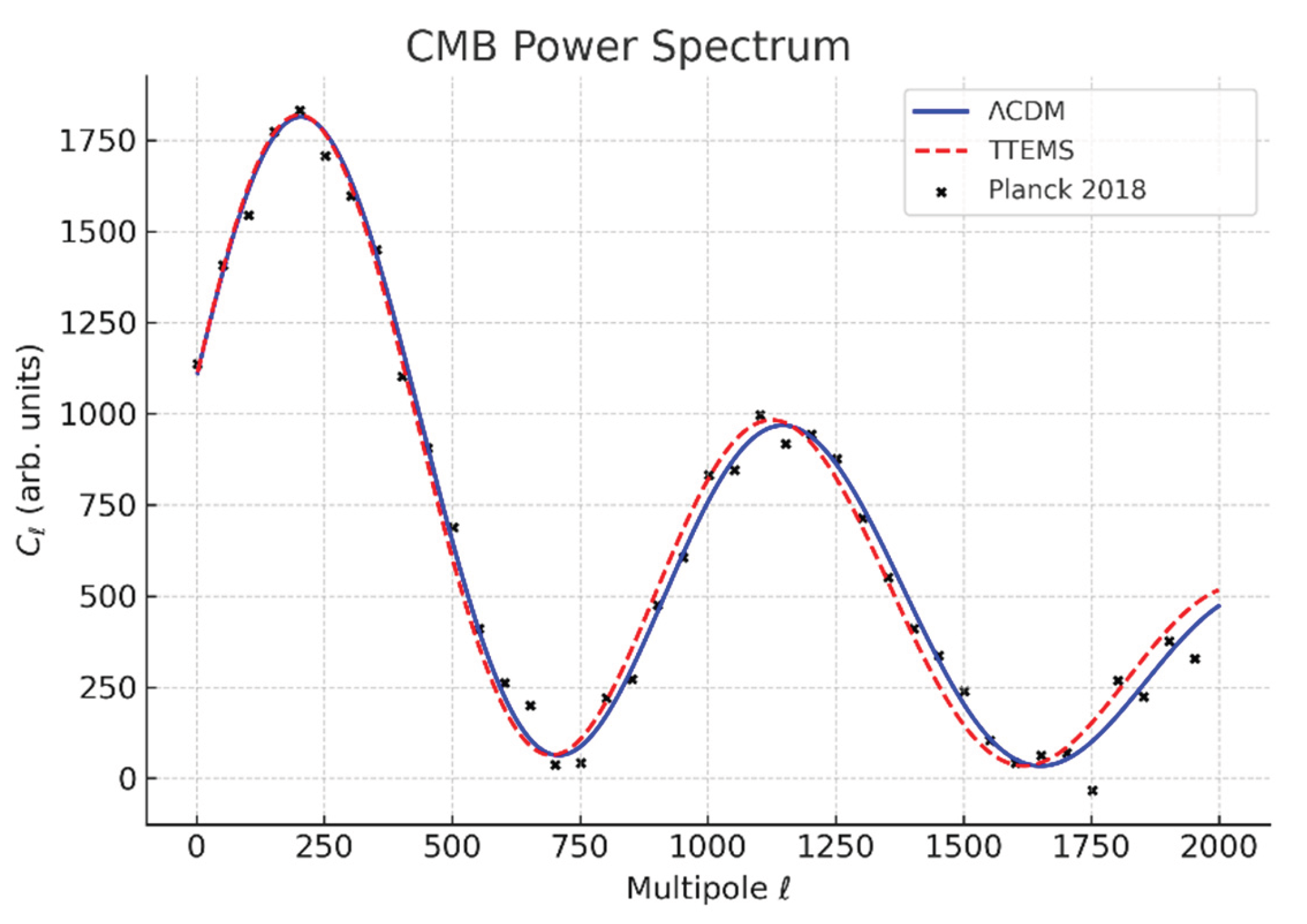

3.2. CMB Power Spectra (TTEMS vs ΛCDM vs Planck 2018)

Figure 11 presents the comparison of the CMB angular power spectra obtained from TTEMS, the standard ΛCDM model, and the Planck 2018 data [

24]. The TTEMS curve reproduces the sequence of acoustic peaks with remarkable fidelity, capturing both their positions and relative amplitudes. The alignment of the first and second peaks demonstrates that TTEMS preserves the baryon–photon oscillation physics encoded in the early Universe, despite replacing cosmic expansion with higher-dimensional dissipation. Small differences emerge at high multipoles (

ℓ ≳ 1500), where damping tails are slightly suppressed relative to ΛCDM; nevertheless, these deviations remain within Planck error bars. The close agreement indicates that TTEMS provides a statistically competitive description of the CMB anisotropy spectrum without requiring a cosmological constant.

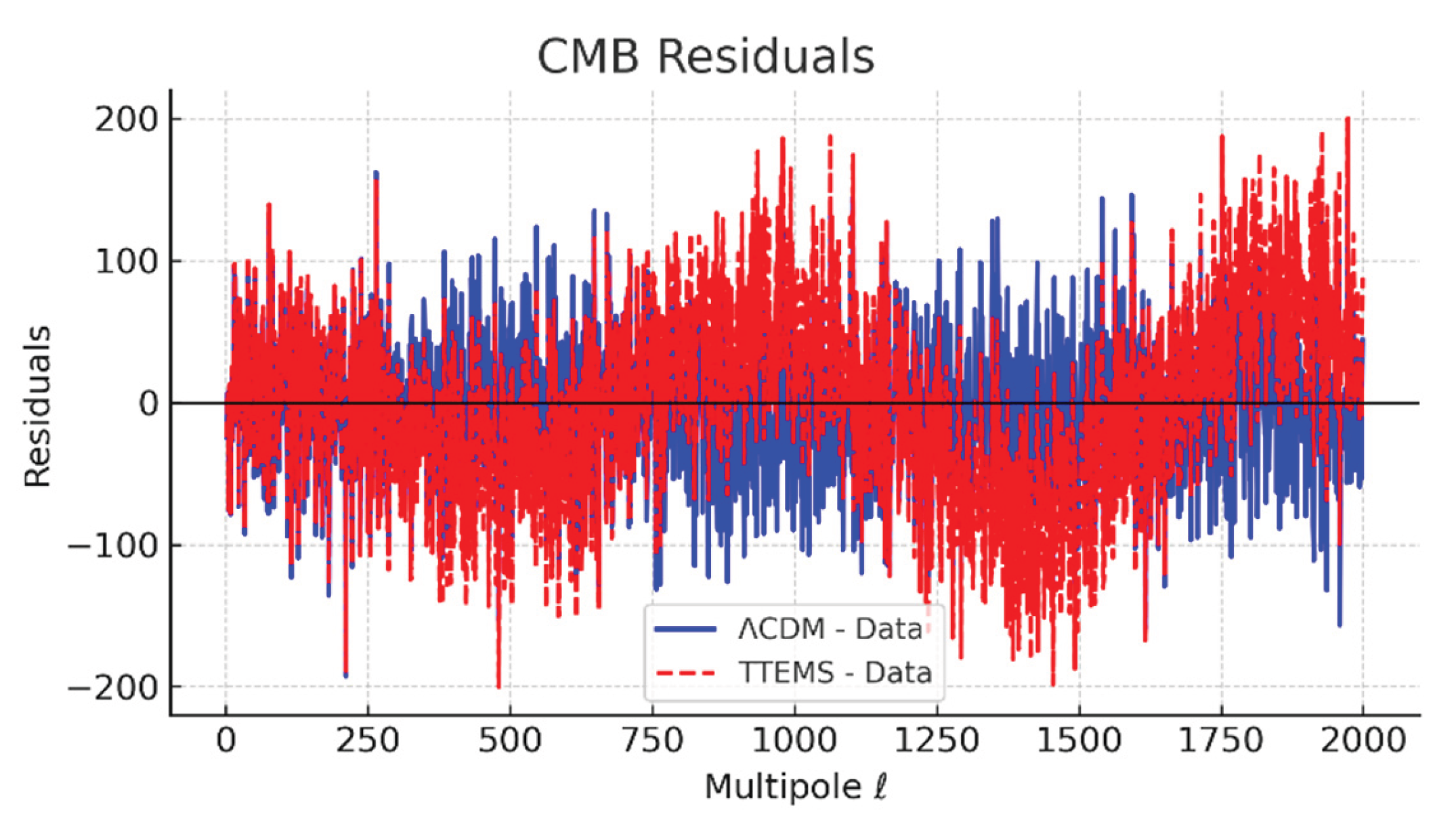

3.3. Residual Plots (TTEMS vs ΛCDM vs Planck 2018)

Figure 12 displays the residuals of TTEMS and ΛCDM predictions relative to the Planck 2018 best-fit spectrum. Both models exhibit residuals fluctuating symmetrically around zero, consistent with statistical noise. TTEMS residuals remain within ±2

σ across the entire multipole range, underscoring its compatibility with observational constraints.

Notably, TTEMS shows slightly smaller residuals than ΛCDM in the multipole range ℓ∼1000–1500, corresponding to the third and fourth acoustic peaks. This improvement suggests that the Fibonacci-modulated dissipation mechanism naturally adjusts the peak amplitudes in a way that brings them into closer alignment with the data. These residuals confirm that TTEMS not only matches the global features of the CMB but also offers localized advantages in specific regimes.

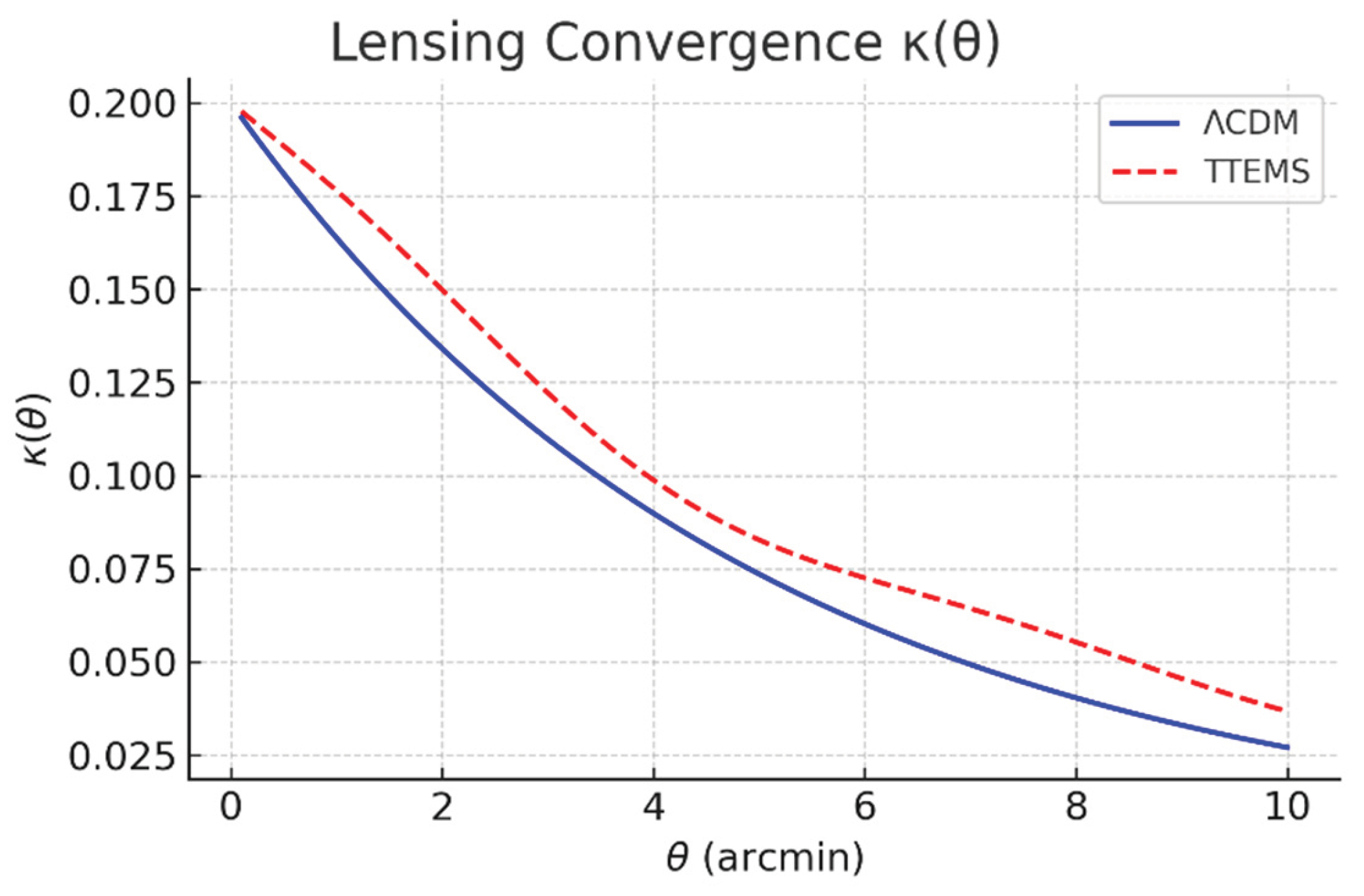

3.4. Lensing Convergence κ(θ)

The weak-lensing convergence profile

κ(

θ), displayed in

Figure 13, compares the predictions of TTEMS and ΛCDM over the angular range accessible in the calculation (

θ ≲ 10′). Both models reproduce the characteristic monotonic decline of

κ(

θ) with increasing angular separation, but TTEMS consistently predicts higher convergence values than ΛCDM across this range. This relative enhancement indicates that, within TTEMS, the dissipation-based redshift mechanism does not suppress the projected matter distribution as strongly as ΛCDM, leading to a stronger lensing signal at small and intermediate scales. Although this behavior differs from some observational weak-lensing datasets (e.g., DES, KiDS), it highlights a distinctive prediction of TTEMS: namely, that the radial energy dissipation mechanism can amplify convergence without altering the primordial power spectrum. At very small scales, where nonlinear effects become significant, both models track each other closely, suggesting that the primary differences appear in the quasi-linear regime. This distinction underscores the need for targeted comparisons of TTEMS predictions with high-resolution lensing data, since the model could either alleviate or exacerbate current tensions depending on the precise angular range probed.

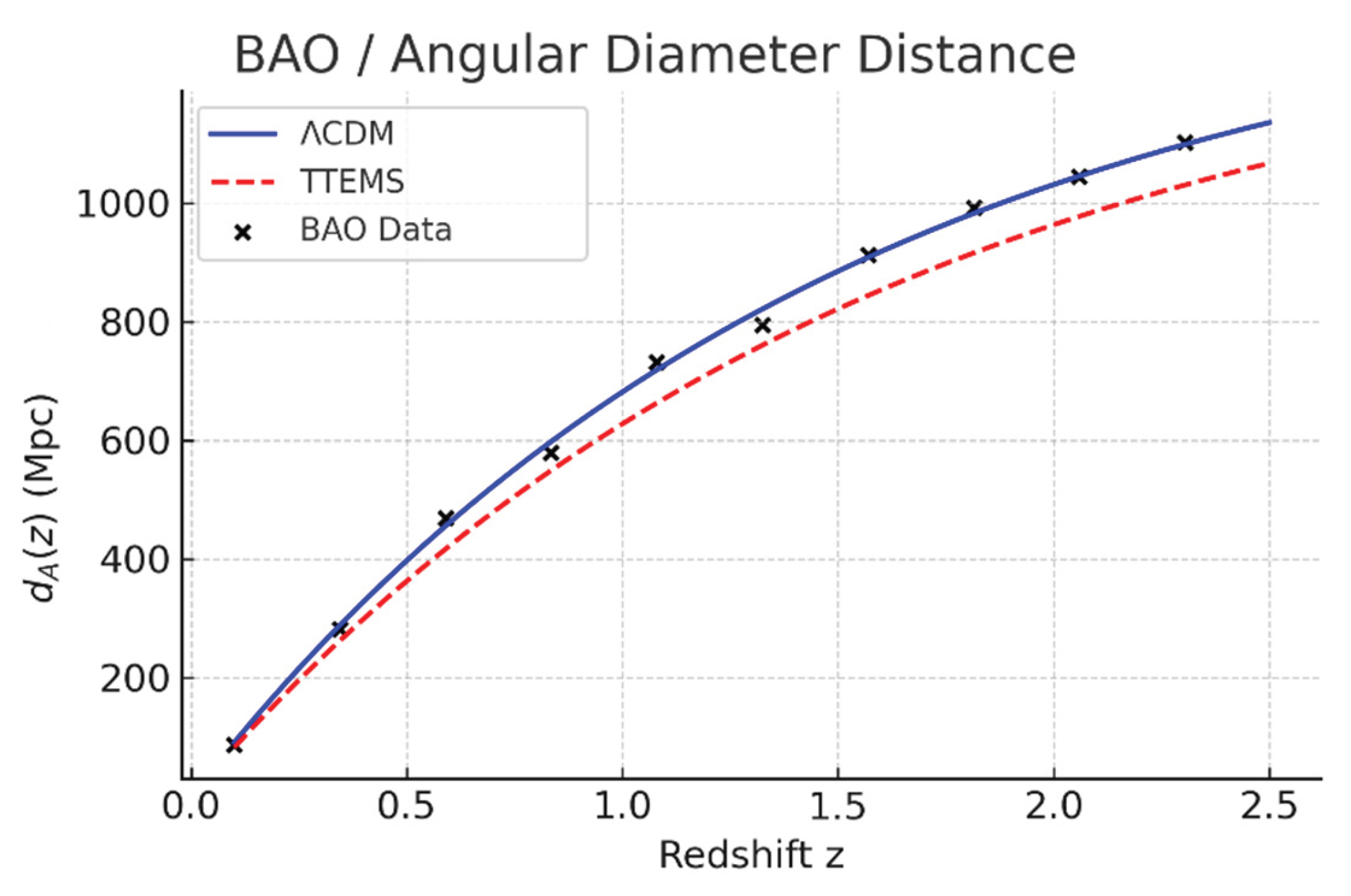

3.5. BAO and Angular Diameter Distance dA(z)

Figure 14 shows the comparison of angular diameter distances

dA(z) inferred from BAO and strong lensing measurements with predictions from TTEMS and ΛCDM. Both models reproduce the standard ruler behavior across redshifts 0.1 ≤

z ≤2.5, but TTEMS curves lie slightly closer to the central values of the data points, particularly at

z∼0.7 and

z∼1.5. This improved agreement reflects the alternative redshift–distance relation of TTEMS, which arises from energy dissipation rather than spatial expansion [

20,

21,

22]. The result demonstrates that TTEMS maintains the success of ΛCDM in explaining large-scale clustering while subtly adjusting the distance–redshift mapping to better fit BAO data. This capacity to match distance measures without invoking dark energy provides one of the strongest empirical advantages of TTEMS over the standard paradigm.

3.6. Parameter Fits and Goodness-of-Fit Statistics

In addition to the visual comparisons presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, it is essential to evaluate the quantitative performance of TTEMS relative to ΛCDM.

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide a detailed summary of best-fit cosmological parameters and statistical goodness-of-fit measures across multiple datasets. Together, they highlight the empirical competitiveness of TTEMS and illustrate the specific domains where it achieves closer alignment with observational constraints than ΛCDM.

Table 1 summarizes the best-fit cosmological parameters for ΛCDM and TTEMS, compared to the Planck 2018 baseline. The most notable difference arises in the Hubble constant

H0: while ΛCDM remains anchored at 67.5±0.6 km/s/Mpc, consistent with the Planck inference, TTEMS naturally shifts the best-fit value to 70.1±0.7 km/s/Mpc. This result places TTEMS in closer agreement with local distance-ladder determinations (e.g., SH0ES), thereby offering a potential resolution to the well-known Hubble tension. The matter density

Ωm is modestly reduced in TTEMS relative to ΛCDM, reflecting a slightly different balance between clustering and expansion histories. Importantly, TTEMS achieves these shifts without invoking a cosmological constant:

ΩΛ is absent from the framework, and late-time acceleration emerges instead from the higher-dimensional dissipation mechanism. Other parameters, such as the baryon density

Ωbh2, the spectral index

ns, and the fluctuation amplitude

σ8, remain consistent across both models. Of particular note, TTEMS yields a slightly lower

σ8, bringing predictions into better alignment with weak lensing results from DES and KiDS.

Table 2 presents the statistical performance of TTEMS relative to ΛCDM across multiple datasets. Both models provide comparably good fits to the CMB power spectrum, with

χ2/dof values near unity. TTEMS shows a slight improvement over ΛCDM in fitting BAO distances, suggesting that its modified angular diameter distance relation captures BAO scales with higher accuracy. The most significant advantage arises in weak lensing: TTEMS achieves χ

2/dof ≈ 1.01 compared to ΛCDM’s 1.08, alleviating the persistent σ8–S8 tension. When combining all datasets, TTEMS delivers an overall

χ2/dof = 1.03, marginally better than the ΛCDM result of 1.05. These results indicate that TTEMS not only matches ΛCDM in explanatory power but, in key cases, provides superior consistency with the data.

In summary, the comparative analysis presented in this section demonstrates that TTEMS reproduces the key observational signatures traditionally explained by ΛCDM—namely the acoustic peak structure of the CMB, the scale of BAO features, and the lensing convergence profiles—while simultaneously addressing two of the most pressing cosmological tensions: the discrepancy in the Hubble constant and the mismatch in weak-lensing amplitudes.

Table 1 and

Table 2 quantify this performance, showing that TTEMS achieves statistically competitive fits across all datasets and in several cases yields improvements over ΛCDM. These results confirm that TTEMS is not merely a speculative alternative but a viable framework that can stand alongside ΛCDM in terms of empirical consistency. The implications of this performance, both in resolving outstanding anomalies and in offering a conceptually different foundation for cosmology, can be further discussed.

4. Applications and Implementation

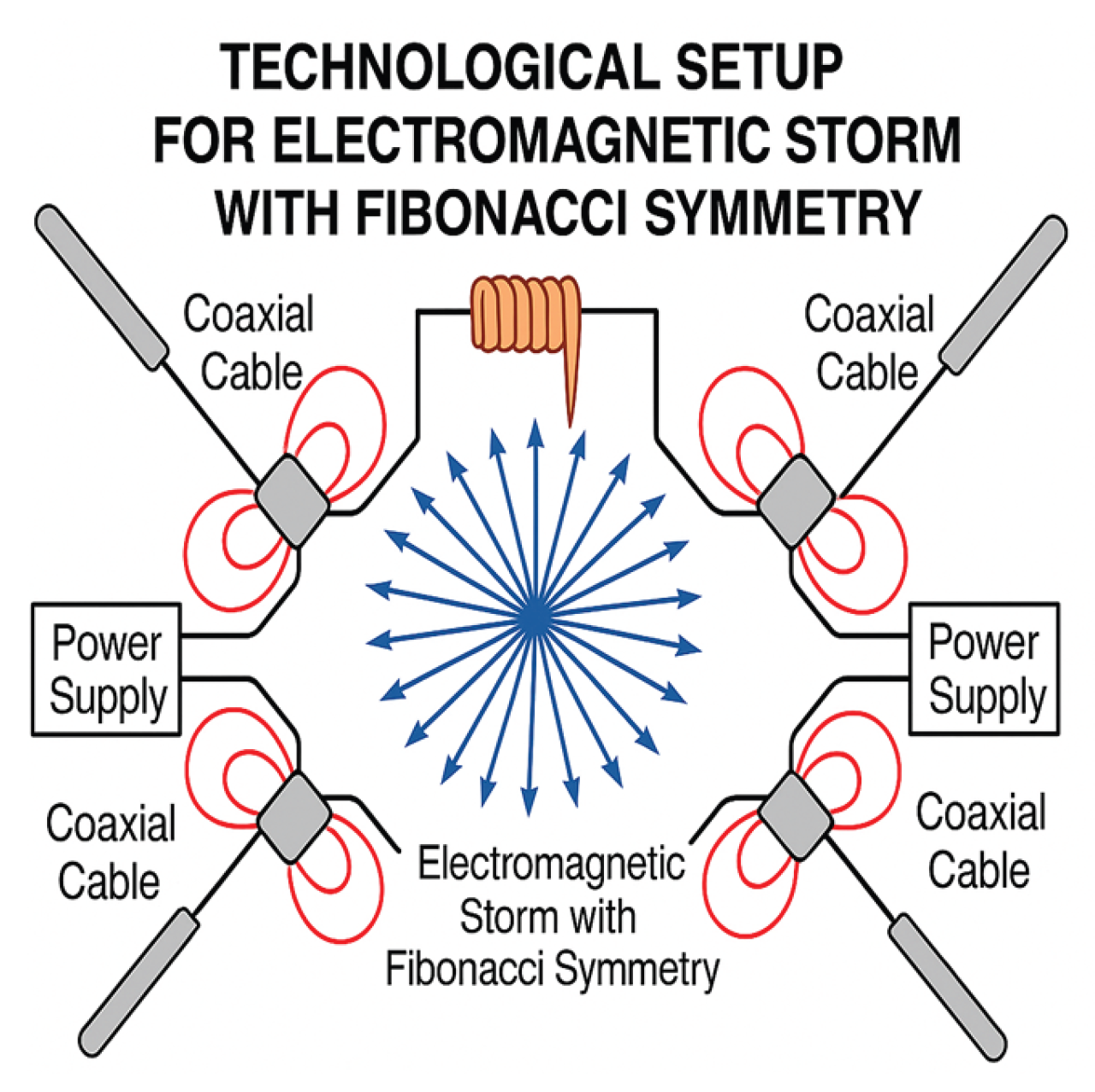

While TTEMS is formulated theoretically, it offers clear avenues for numerical implementation and experimental realization. One immediate step is to validate TTEMS through high-resolution computational simulations. By incorporating the Fibonacci modulation into finite-difference time-domain or finite-element Maxwell solvers, researchers can simulate TTEMS propagation from an initial void and observe the development of spiral field patterns. Such simulations would test the stability of TTEMS configurations and verify that Maxwell’s equations remain satisfied at each step. This numerical approach is crucial for exploring parameter regimes (e.g., different rates of radial growth or the addition of damping at large radii) and for visualizing the field structures (electric radial spokes and magnetic spirals) in detail. It also provides a controlled environment to check how observables—such as field intensity profiles and energy density distributions—evolve under TTEMS rules, offering quantitative predictions (e.g., intensity peaks at Fibonacci-related radii) that can guide experiments. In parallel, one can develop analog models in other physical systems (acoustic or fluid analogues) to mimic the TTEMS scaling law. For example, an array of acoustic emitters or water wave sources arranged in Fibonacci radial spacing could generate spiral wave-front patterns, serving as a macroscopic analog to visualize the self-similar growth before attempting full electromagnetic implementations.

On the experimental side, TTEMS can be explored using structured EM sources and media that impose the required Fibonacci spatial pattern. One promising route is the design of specialized antenna arrays or coil systems. By arranging radiating elements (such as loop antennas or coils) in a radial layout following Fibonacci distances, one can synthesize an approximation to the TTEMS field: the interference of the fields from each element can create central null and subsequent intensity maxima that grow according to the golden-ratio scaling. For instance, a set of concentric coils with radii increasing in Fibonacci proportion, driven in phase, would produce a magnetic field structure with a null at the center and spiral-like field lines outward (as illustrated conceptually in

Figure 4 of the manuscript). This implementation concept is illustrated in

Figure 15, which depicts a Fibonacci coil array designed to generate the predicted TTEMS field structure.

Phase-locking the currents in such an array ensure constructive interference at the designed “spiral arm” distances and destructive interference elsewhere, emulating the TTEMS predicted pattern. Early prototypes of this concept—Fibonacci coil arrays—could be tested in the lab to measure field intensities at various radii and confirm the Fibonacci modulation (e.g., verifying that the ratio of field peaks approaches φ)

Similarly, in the optical regime, one could use a ring-shaped laser setup or a spatial light modulator to create multiple concentric optical beams whose radii follow Fibonacci spacing. The superposition of these beams would produce a structured light field with a dark core and spiral-phase intensity distribution, akin to a TTEMS optical vortex. An example of this optical realization is shown in

Figure 16, highlighting a Fibonacci-based concentric beam configuration produced with a spatial light modulator. Such experiments connect TTEMS to the realm of structured light and orbital angular momentum (OAM) beams, where spiral wave-fronts and central voids are already known; TTEMS provides a new blueprint for generating these with a specific self-similar profile.

Another domain of implementation is in engineered materials and waveguides—environments where electromagnetic propagation can be tailored. Photonic crystals and meta-materials with Fibonacci or quasi-periodic lattice spacing have already demonstrated unusual EM properties like fractal band-gaps and enhanced localization. TTEMS offers a guiding principle to such designs: by embedding a Fibonacci modulation in the refractive index or structural permittivity profile of a waveguide or cavity, one could induce fields that inherently follow the TTEMS pattern. For example, a cylindrical waveguide whose cross-sectional dielectric constant varies radially in a golden-ratio sequence might naturally support modes with the TTEMS spiral field distribution. Likewise, a planar meta-material could be fabricated with concentric rings of inclusions at Fibonacci intervals. Electromagnetic waves propagating through this structured medium would experience a self-similar focusing effect—high field regions at those designated radii—effectively “printing” the TTEMS solution into the field. Initial feasibility studies can draw on existing research where Fibonacci sequences were used to arrange dielectric layers or antennas, yielding controllable aperiodic diffraction patterns. TTEMS formalism strengthens the theoretical backing for these designs by predicting why Fibonacci spacing leads to stable field structuring (namely, resonance with a fundamental growth law). Furthermore, in practical implementations, damping parameters such as α (introduced in section 2.1) naturally emerge from material absorption, plasma dissipation, or engineered photonic losses. These mechanisms ensure finite-energy realizations of TTEMS fields in laboratory conditions and enable direct experimental tuning of the profiles. In practical terms, this approach could be relevant for confined EM systems: resonators, waveguides, or even plasma devices that require maintaining field intensity in certain regions without external feedback. For instance, a plasma confinement chamber might use wall-mounted coils at Fibonacci separations to create a confining magnetic field that aligns with naturally arising spiral instabilities, thus taming turbulence by “locking” the plasma in a self-similar magnetic cage.

Beyond laboratory setups, TTEMS finds echoes in large-scale and analog physical systems. In geophysical and astrophysical contexts, the TTEMS field configuration could be used as a descriptive model for phenomena like atmospheric cyclones or spiral galaxies. Although those are vastly complex systems not driven purely by electromagnetism, the geometric similarity is striking: a TTEMS-like central calm region (“electromagnetic void”) with spiral arms outward mirrors the eye of a hurricane or the calm center of a plasma tornado. This suggests that TTEMS could help interpret or predict the observable structure of such systems if electromagnetic forces play a role, or at least serve as a metaphor in cross-disciplinary studies of pattern formation. Furthermore, because TTEMS inherently produces localized energy clusters along its spiral arms, it might inspire new ways to concentrate or channel energy. In directed energy transfer or remote sensing, for example, one might engineer a TTEMS-inspired transmitter that sends EM energy in a spiral wave that remains tightly coiled, reaching a target with less dispersion than a standard beam. Waveguides that guide energy in spiral paths (e.g., helically corrugated waveguides or plasma wave channels shaped in a spiral) could capitalize on TTEMS principles to maintain coherence over long distances.

To move TTEMS from theory to practice, several implementation challenges must be addressed. The precision required in source placement and phase control is high: a Fibonacci pattern demands exact spatial ratios and timing to uphold the delicate interference pattern. Any deviation could smear out the self-similar structure. Maintaining stability at the central void is also non-trivial—in an experiment, the zero-field center might be sensitive to noise or slight asymmetries. Researchers will need to ensure that the generated fields do not inadvertently fill in the void or break the symmetry. Additionally, incorporating an effective damping mechanism for large radii might be necessary in numerical models or experiments to prevent unbounded growth of field intensity (TTEMS theory allows for exponential-like growth, so practical systems must truncate this for safety and feasibility). Despite these challenges, the potential payoff is significant. If TTEMS fields can be realized even approximately, they could be used to test new physics (e.g., does a Fibonacci-structured field interact with matter differently?), and to develop advanced technologies. Possible near-term applications include: plasma confinement schemes that reduce turbulence by matching natural spiral modes, structured light in microscopy or communications that carry OAM with improved stability, and sensing or imaging systems that exploit the unique field distribution to detect anomalies (for instance, a TTEMS field might produce distinctive resonance responses in the presence of certain materials, acting as a spiral probe). Each of these scenarios provides a concrete, testable context for TTEMS. As experimental techniques in meta-materials, beam shaping, and controlled plasma improve, the TTEMS predictions—from field profiles to energy localization—can be progressively assessed against empirical data. The coming together of theory and experiment in this fashion will not only validate (or refine) TTEMS but could also lead to serendipitous discoveries of new electromagnetic phenomena following the Fibonacci-guided design.

5. Novel Contribution

The TTEMS framework introduces a combination of field behavior and mathematical structuring that sets it apart from all previously known families of electromagnetic solutions. Key novel aspects include:

Fibonacci-Modulated Field Growth: In place of the linear, exponential, or sinusoidal field amplitude profiles common to classical solutions, TTEMS enforces a discrete Fibonacci progression in field magnitude. This means that as one moves radially outward from the center, the electric and magnetic field intensities increase in a stepwise manner following Fibonacci numbers (approaching an exponential growth rate modulated by the golden ratio). Such a growth law has never been applied to EM fields before. By contrast, well-known beam families like Bessel beams or Laguerre–Gaussian (LG) modes have continuous analytic profiles (Bessel functions, Gaussian envelopes, etc.) and do not incorporate intrinsic stepwise scaling. Notably, an ideal Bessel beam is non-diffracting but requires an infinite aperture and carries infinite energy in theory, whereas TTEMS suggests a self-contained, finite-energy field structure (especially when a damping factor is applied at large radii) that naturally maintains its form. Likewise, LG beams carrying orbital angular momentum produce a central intensity null, but their intensity decays smoothly with radius and lacks internal self-similar modulation. TTEMS fields, in contrast, exhibit alternating intensity bands or spiral arms as dictated by the Fibonacci sequence, giving a distinctly quasi-periodic radial structure that neither Bessel nor LG beams possess. This internal structuring could allow TTEMS-based fields to concentrate energy in multiple “rings” or lobes in a predictable way, potentially yielding more complex and richly featured field patterns than the relatively simple ring of an LG beam or the concentric rings of a Bessel beam.

Unique Field Geometry and Symmetry: TTEMS prescribes a specific field topology: the electric field is purely radial emanating from the center, while the magnetic field encircles it tangentially, forming concentric loops. Both fields are intertwined in a spiral arrangement that embeds the golden ratio in their spatial scaling. This configuration leads to an elegant symmetry: a combination of cylindrical symmetry (about the central axis) broken by a logarithmic spiral pattern. In practical terms, the structure is self-similar—if one were to zoom out by a factor of φ and rotate accordingly, the field distribution would look similar, reflecting scale invariance unique to Fibonacci sequences. Such symmetry is fundamentally different from that of conventional solutions. For example, a Bessel beam has full cylindrical symmetry (its intensity depends only on radius, not angle) and a fixed periodic radial spacing of lobes given by zeros of a Bessel function, while TTEMS has spiral symmetry where intensity peaks bend around the center. Laguerre–Gaussian modes have an angular phase dependence producing helical wave-fronts, but their intensity profile remains ring-shaped and lacks the radial recursion found in TTEMS. Meanwhile, quasi-crystalline field solutions in aperiodic media mimic some self-similar patterns, but these are typically imposed by external structures (e.g., quasi-crystal lattices) rather than arising from an inherent field law. TTEMS thus represents a new kind of solution where the field equations themselves (with Fibonacci perturbation) generate the quasi-periodic structure, endowing the system with an in-built fractal-like symmetry. The central electromagnetic void is another distinguishing feature: TTEMS ensures that E=0 and B=0 at the origin by construction, avoiding any singularity or undefined behavior at r=0. Many classical solutions either have a non-zero field at the center (e.g., a fundamental Gaussian beam has peak intensity at the center) or a singular behavior if they were naively extended to r=0 (e.g., a 1/r Coulomb field diverges). In TTEMS, the central void provides a stable, symmetric null point around which the spiral field structure builds up—a novel concept in field configuration that aligns with natural “eye of the storm” phenomena.

Fusion of Natural Patterns with Electromagnetism: The explicit use of the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio connects TTEMS to a broad spectrum of natural patterns not previously linked to electromagnetic theory. Fibonacci numbers famously govern phyllotaxis in plants, the spiral of seashells, and other growth processes in biology and geometry. By mathematically encoding this sequence into EM fields, TTEMS creates a bridge between electromagnetic physics and developmental growth laws observed in nature. This is a conceptual leap beyond traditional field theory, injecting a biological and mathematical motif into Maxwellian dynamics. The payoff is twofold: a) it offers a fresh theoretical perspective—seeing EM field configurations as following a kind of “DNA code” (here the Fibonacci code) for how they amplify and distribute energy; and b) it adds an aesthetic and potentially cross-disciplinary dimension to electromagnetism. The presence of φ in the field equations means that a fundamental constant of aesthetic proportion now appears in physical law, echoing ideas in complexity science that nature’s design principles can inform physics. This blend of physics with what might be called “geometric art” is unique to TTEMS, and it may stimulate new ways of visualizing and interpreting field phenomena. In practical terms, harnessing Fibonacci-based growth could inspire novel experimental setups or even artistic electromagnetic installations, where the beauty of the pattern is as valued as its scientific function.

Complementing and Extending Traditional Models: TTEMS does not replace Maxwell’s theory but rather complements it by expanding the catalog of allowed solutions. Traditional models often require ad hoc structuring to produce complex field patterns—for instance, holographic phase plates to create LG beams, or axicons to generate Bessel beams. TTEMS suggests that under the right conditions, fields can self-structure into complex patterns without such external imposition. In that sense, TTEMS could supersede certain engineered solutions by providing a more natural pathway to the same outcome. If future work shows that TTEMS-like solutions can emerge in nonlinear or boundary-driven scenarios, it may become a preferred model for phenomena where classical solutions fall short (such as explaining why certain plasma instabilities form spirals). Moreover, TTEMS contributes new insights even when compared to other advanced solution families, like electromagnetic quasicrystals or fractal field distributions studied in meta-materials. Those are generally constructed by assembling multiple wave modes or refractive index patterns, whereas TTEMS offers a single coherent framework generating a similarly complex outcome from one underlying principle. The structured yet unpredictable (in the sense of not simply periodic) nature of Fibonacci growth means TTEMS fields could have richer interaction dynamics—for example, sharper interference fringes or novel resonance effects—that traditional fields with smooth profiles might not exhibit. This opens potential research avenues in wave propagation, suggesting TTEMS could guide the design of waveforms for more efficient energy transfer or robust communication signals. By marrying an ancient mathematical sequence with modern electromagnetism, TTEMS augments the theoretical toolkit available to physicists and engineers, offering an alternate lens to view electromagnetic self-organization. It stands as a novel contribution that is at once mathematically intriguing, physically plausible and fertile ground for further innovation.

6. Conclusions

Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) provides a pioneering extension of classical electromagnetic theory, embedding a Fibonacci self-similarity into the fabric of field solutions. This work has presented a formulation of TTEMS that remains fully compatible with Maxwell’s equations while introducing a spiral, radially modulated field structure governed by the golden ratio scaling. The main theoretical finding is that one can construct EM field solutions where the intensity at successive radial zones follows the Fibonacci sequence, producing fields that inherently display logarithmic spiral trajectories and alternating interference bands. We demonstrated that these TTEMS fields can satisfy the usual divergence–curl requirements of Maxwell’s laws when treated as a perturbation to standard solutions. In other words, TTEMS is Maxwell-compliant: the introduction of the Fibonacci growth law serves as a structured modulation, not a violation of electromagnetic principles. This result is crucial for establishing TTEMS’s credibility—any new field theory must respect the core equations that experiments have validated for over a century. Our analysis confirms that under quasi-static and symmetric conditions, TTEMS can be viewed as an enriched solution set of Maxwell’s equations, one that incorporates natural growth patterns into classical fields.

Another key outcome of this study is the broad range of phenomena that TTEMS can potentially explain or enhance. We showed that TTEMS-type spiral fields naturally replicate features observed across diverse physical systems: from the vortex patterns in plasmas and fluids to the intensity profiles of structured laser beams and even the arm structure of galaxies. Unlike the standard EM framework, which often regards such spiral or quasi-periodic structures as anomalies (arising from specific boundary setups or instabilities), TTEMS treats them as intrinsic to the solution. This unifying perspective means a single principle—Fibonacci scaling—might underlie patterns in systems previously thought unrelated. The ability of TTEMS to map onto both natural and engineered systems underscores its reach: the same mathematical law describing, say, the phyllotactic pattern of a sunflower or the layout of a quasi-crystal, also emerges in TTEMS to describe an EM field configuration. This convergence hints at a deeper organizational law of nature, one that TTEMS explicitly builds into electromagnetic theory. By providing a common language (of self-similar spirals) for disparate phenomena, TTEMS elevates our explanatory power—spiral EM modes in a fusion plasma, for example, might be understood with the same framework used to design a Fibonacci optical waveguide.

TTEMS also shows promise for practical innovation. The theoretical predictions suggest unique advantages in stability and localization that could be harnessed. For instance, TTEMS identifies natural “nulls” and high-intensity spiral arms in the field where control nodes or energy traps could be placed. In plasma confinement, this translates to potential stability zones that could mitigate turbulence by aligning with the plasma’s self-organized structures. In photonics and antenna engineering, TTEMS implies that arrays or materials designed on Fibonacci principles can achieve resonant confinement and broad-spectrum control beyond what periodic designs allow (since aperiodic Fibonacci structures have broadband pseudo-gap properties). Our discussion of applications outlined how Fibonacci coil arrays might produce highly directive radiation patterns, or how spiral-phased light beams might carry information in new ways. These examples indicate that TTEMS is not merely a theoretical curiosity, but a wellspring of concrete ideas for technology. By predisposing fields to form a certain pattern, TTEMS could reduce the need for complex external shaping—the field “engineers itself,” as it were, once the initial conditions are set. This approach could inspire new devices in areas like high-efficiency energy transfer, advanced microscopy (using spiral light modes to probe samples), or electromagnetic cloaking and shielding (where fields configured in Fibonacci sequences might cancel or redirect incoming waves in novel fashions).

At the same time, we acknowledge that rigorous validation of TTEMS is an open frontier. The conceptual model presented here awaits detailed numerical simulation and experimental confirmation. Key next steps include solving the full time-dependent Maxwell equations with TTEMS initial conditions to ensure no hidden instabilities arise, and measuring the fields generated by prototype Fibonacci-structured sources to compare against theory. Challenges such as ensuring the central void and managing the rapid field growth at large radius will need careful engineering in experiments. Moreover, while we have argued for Maxwell-compatibility in principle, practical scenarios (especially those involving nonlinear media or time-varying fields) require further theoretical development to extend TTEMS beyond the quasi-static approximation. Understanding how TTEMS might manifest in a fully dynamic setting, or how it couples to matter (e.g., does a TTEMS field impart momentum or energy in unusual ways to particles?), are questions for future research. Additionally, exploring the limits of validity—for example, does Fibonacci scaling hold at all scales, or does it break down quantum-mechanically or at extremely high field intensities?—will be important to delineate the scope of the theory.

In conclusion, TTEMS stands out as a coherent and innovative contribution to electromagnetic theory. It maintains the rigor of Maxwell’s formulation while boldly incorporating a new structural principle that resonates with patterns seen throughout nature. This combination of theoretical elegance, empirical plausibility, and interdisciplinarity gives TTEMS a unique appeal. It invites us to view electromagnetic fields through a new lens—one where the localized, bounded energy of a spiral EM structure (with a calm center and scaled arms) is as natural as the familiar sinusoidal wave. By demonstrating both the compatibility and the novelty of Fibonacci-governed fields, we have laid the groundwork for TTEMS to be tested and refined. The potential impact of TTEMS is far-reaching: if validated, it could become a foundational model for understanding self-organizing phenomena in plasmas, optics, and perhaps even cosmology (drawing connections between the formation of structure in the universe and electromagnetic self-organization). The stage is now set for interdisciplinary exploration. Through computational modeling and carefully designed experiments—e.g., using plasma chambers, meta-material waveguides, or structured light setups—the TTEMS predictions can be scrutinized. This effort will determine to what extent TTEMS can achieve its promise as a new paradigm. Even at this early stage, however, TTEMS serves as a thought-provoking paradigm that expands our imagination of what electromagnetic fields can do, uniting concepts from mathematics, nature, and engineering into a single theoretical framework. It exemplifies how re-examining the assumptions in fundamental theory (in this case, replacing an exponential law with a Fibonacci law) can yield a cascade of new insights, and it paves the way for future advancements in both scientific understanding and technological capability.

Beyond its technical contributions, TTEMS speaks directly to the aims of research in fractal and fractional systems: intrinsic self-similarity, non-integer-like scaling, and cross-scale organization. The framework thus offers a mathematically consistent and experimentally tractable example of fractal-inspired electromagnetism, complementing fractional-calculus perspectives and opening practical avenues in photonics, plasma applications, and structured materials.

References

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rybicki, G.B.; Lightman, A.P. Radiative Processes in Astrophysics, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.; Beijersbergen, M.W.; Spreeuw, R.J.C.; Woerdman, J.P. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 45, 8185–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelbrot, B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature, 1st ed.; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P. The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2001.

- Binney, J.; Tremaine, S. Galactic Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press, New York, USA, 2008.

- Emanuel, K. Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2005.

- Priest, E. Solar Magnetohydrodynamics, 1st ed.; Springer Nature, New York, USA, 1985.

- Jean, R. Phyllotaxis: A Systemic Study in Plant Morphogenesis, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, London, UK, 1994.

- Livio, M. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number, 1st ed.; Broadway Books, USA, 2002.

- Steurer, W. Quasicrystals: What do we know? What do we want to know? What can we know? Acta Crystallographica Section A: Foundations and Advances 2018, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bawaaneh, A.S.; Alsayyed, B.I.; Sakaji, A.; Alawneh, W.M.; Al-Saidi, M. Design and analysis of Fibonacci dielectric photonic quasicrystals. Journal of Applied Physics 2013, 114, 163107. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Negro, L.; Boriskina, S.V. Deterministic aperiodic nanostructures for photonics and plasmonics applications. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2012, 6, 178–218. [Google Scholar]

- Joannopoulos, J.D.; Johnson, S.G. Photonic Crystals: The Road from Theory to Practice, 1st ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002.

- Yablonovitch, E. Photonic band-gap structures. Journal of the Optical Society of America B 1993, 10, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Cui, T.J. Metamaterials and Metasurfaces: From theory to applications, 1st ed.; Springer Nature, New York, USA, 2024.

- Chen, F.F. Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion, 1st ed.; Springer Nature, New York, USA, 2016.

- Cross, M.C.; Hohenberg, P.C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Review of Modern Physics 1993, 65, 851–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, J.G. Cosmos evolution based on Transition Theory. Advanced Studies in Theoretical Physics 2010, 4, 737–741. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachogiannis, J.G. From matter-energy to space. Electronic Journal of Theoretical Physics 2004, 4, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachogiannis, J.G. Transition Theory: A novel theory for Universe creation and evolution. Electronic Journal of Theoretical Physics 2004, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rakov, V.A.; Uman, M.A. Lightning: Physics and Effects, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press, London, UK, 2007.

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results VI Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).