Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| LLM | Large language models |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

References

- Badshah A, Rehman GU, Farman H, Ghani A, Sultan S, Zubair M, Nasralla MM. Transforming educational institutions: harnessing the power of internet of things, cloud, and fog computing. Future Internet 2023;15:11:367. [CrossRef]

- Imran M, Almusharraf N. Google Gemini as a next generation AI educational tool: A review of emerging educational technology. Smart Learning Environments 2024;11:1. [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin M, Shazed Ali M, Salem A, et al. History of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbots: past, present, and future development. Cornell University 2024. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou E, Moussiades L. An overview of chatbot technology. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology 2020;583:373–383. [CrossRef]

- Pavlik EJ, Land Woodward J, Lawton F, Swiecki-Sikora AL, Ramaiah DD, Rives TA. Artificial Intelligence in relation to accurate information and tasks in gynecologic oncology and clinical medicine—Dunning–Kruger effects and ultracrepidarianism. Diagnostics 2025;15:6:735. [CrossRef]

- Colasacco CJ, Born HL. A case of Artificial Intelligence chatbot hallucination. JAMA Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2024 Jun 1;150:6::457-458. PMID: 38635259. [CrossRef]

- Kacena MA, Plotkin LI, Fehrenbacher JC. The use of Artificial Intelligence in writing scientific review articles. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2024 Feb;22:1:115-121. [CrossRef]

- Garrison JA.UpToDate. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2003;91:1:97 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC141198/.

- Pavlik EJ, Ramaiah DD, Rives TA, Swiecki-Sikora AL, Land, JM. Replies to queries in gynecologic oncology by Bard, Bing and the Google Assistant. BioMedInformatics 2024;4:3):1773-1782. [CrossRef]

- Dhammi IK, Ul Haq R. What is plagiarism and how to avoid it? Indian J Orthop. 2016 Nov-Dec; 50:6:581-583. [CrossRef]

- Taylor D. Plagiarism: 5 potential legal consequences. FindLaw 2019. https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/law-and-life/plagiarism-5-potential-legal-consequences/.

- Traniello JF, Bakker TC. Intellectual theft: Pitfalls and consequences of plagiarism. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2016;70:11:1789–1791. [CrossRef]

- Aronson JK. Plagiarism – please don't copy. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2007;64:403-405. [CrossRef]

- Land JM, Pavlik EJ, Ueland E, et al. Evaluation of replies to voice queries in gynecologic oncology by virtual assistants Siri, Alexa, Google, and Cortana. BioMedInformatics 2023;3:3:553-562. [CrossRef]

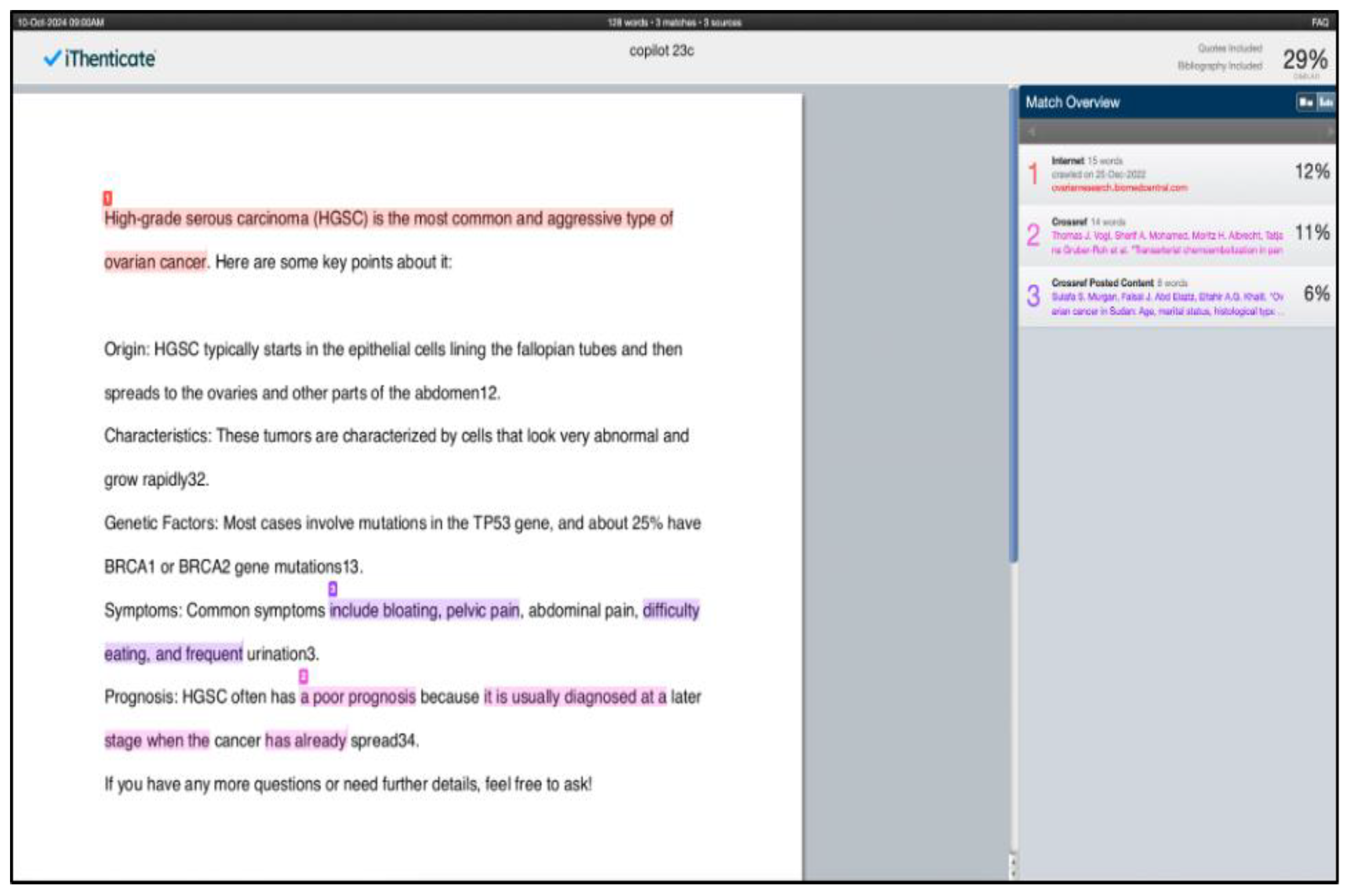

- Turnitin, iThenticate. Plagiarism detection software: Ithenticate 2024. https://www.ithenticate.com/.

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to real abstracts with detectors and blinded human reviewers. NPJ Digit Med. 2023 Apr 26;6:1:75. [CrossRef]

- Longoni C, Tully S, Shariff A. The AI-human unethicality gap: plagiarizing AI-generated content is seen as more permissible. 2023 Jun 18. [CrossRef]

- Dien J. Editorial: generative Artificial Intelligence as a plagiarism problem. Biological Psychology 2023;181:108621. [CrossRef]

- Winstat – the statistics add-in for Microsoft Excel. https://www.winstat.com/.

- Graphpad. https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ttest1/.

- Kacena MA, Plotkin LI, Fehrenbacher JC. The use of Artificial Intelligence in writing scientific review articles. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2024 Feb;22:1:115-121. [CrossRef]

- Colasacco CJ, Born HL. A case of Artificial Intelligence chatbot hallucination. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024 Jun 1;150:6:457-458. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz S. What is Google Bard? Here's everything you need to know. ZDNET. 2024 Feb 9. Available at: https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-google-bard-heres-everything-you-need-to-know/. Accessed 2024 Feb 13.

- Microsoft Copilot. Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microsoft_Copilot. Accessed 2024 Feb 13.

- Vogel M. A curated list of resources on generative AI. Medium. Updated 2024 Oct 9. Available at: https://medium.com/@maximilian.vogel/5000x-generative-ai-intro-overview-models-prompts-technology-tools-comparisons-the-best-a4af95874e94#id_token=eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6IjFkYzBmMTcyZThkNmVmMzgyZDZkM2EyMzFmNmMxOTdkZDY4Y2U1ZWYiLCJ0eXAiOiJKV1QifQ. Accessed 2025 Jan 27.

- Yang J, Jin H, Tang J, et al. The practical guides for large language models. Available at: https://github.com/Mooler0410/LLMsPracticalGuide. Accessed 2025 Jan 27.

- Menz BD, Modi ND, Sorich MJ, Hopkins AM. Health disinformation use case highlighting the urgent need for artificial intelligence vigilance: weapons of mass disinformation. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184:1:92-96. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).