Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Prehabilitation Program Structure: Clinical and Technological Needs

3. IoT and Monitoring System

4. Human Movement Recognition and Intelligent Approaches: Role of ML/AI

5. Digital Twin in Smarthealthcare and Prehabilitation

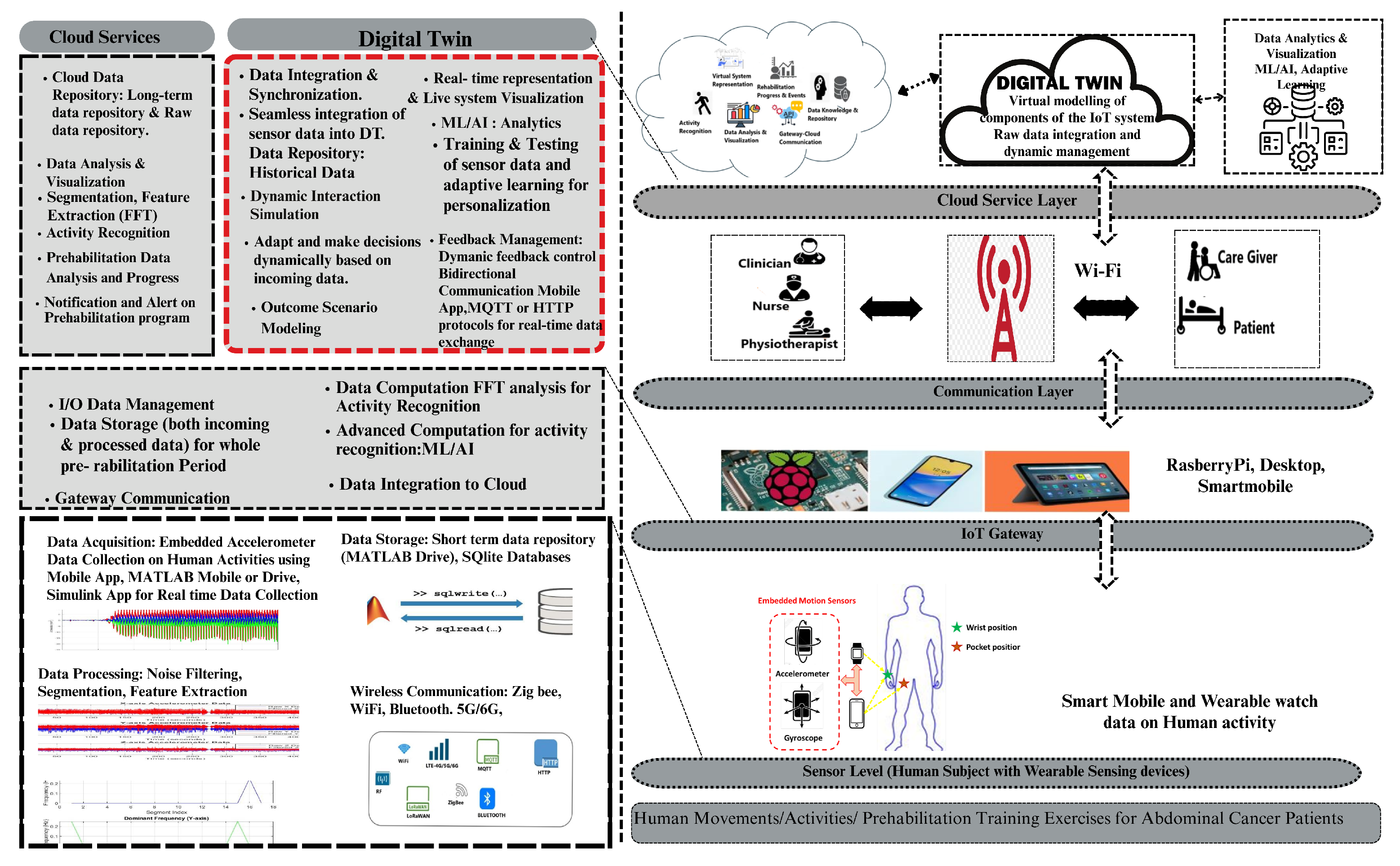

6. IoT Framework for Adaptive Prehabilitation Interventions Using Digital Twin

6.1. Conceptual Framework

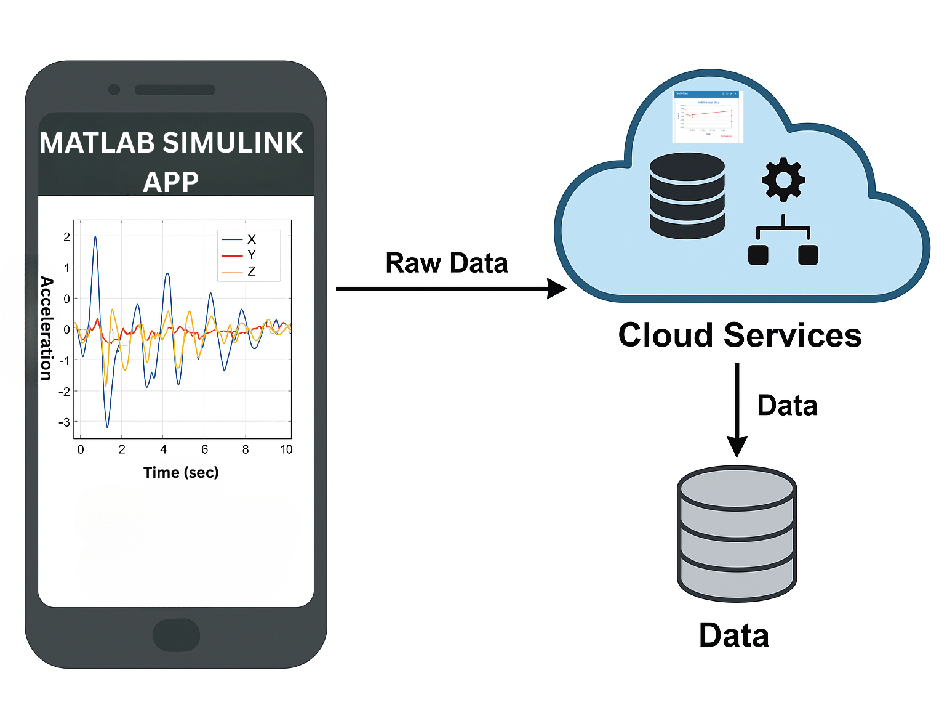

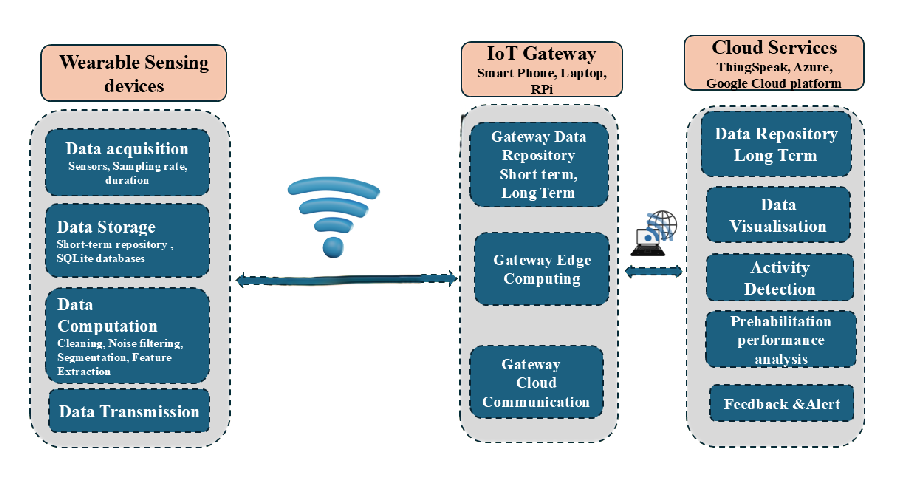

6.1.1. Wearable Activity tracker

6.1.2. IoT Gateway or Edge Level

6.1.3. Cloud-Level Functionality

6.1.4. Digital Twin

7. Conclusions

References

- Daniels, S.L.; Lee, M.J.; George, J.; Kerr, K.; Moug, S.; Wilson, T.R.; Brown, S.R.; Wyld, L. Prehabilitation in elective abdominal cancer surgery in older patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJS Open 2020, 4, 1022–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberan-Garcia, A.; Ubré, M.; Roca, J.; Lacy, A.M.; Burgos, F.; Risco, R.; Momblán, D.; Balust, J.; Blanco, I.; Martínez-Pallí, G. Personalized Prehabilitation in High-risk Patients Undergoing Elective Major Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Blinded Controlled Trial. Annals of Surgery 2018, 267, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, F.; Bousquet-Dion, G.; Awasthi, R.; Elsherbini, N.; Liberman, S.; Boutros, M.; Stein, B.; Charlebois, P.; Ghitulescu, G.; Morin, N.; et al. Effect of Multimodal Prehabilitation vs Postoperative Rehabilitation on 30-Day Postoperative Complications for Frail Patients Undergoing Resection of Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surgery 2020, 155, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIsaac, D.I.; Hladkowicz, E.; Bryson, G.L.; Forster, A.J.; Gagne, S.; Huang, A.; Lalu, M.; Lavallée, L.T.; Moloo, H.; Nantel, J.; et al. Home-based prehabilitation with exercise to improve postoperative recovery for older adults with frailty having cancer surgery: the PREHAB randomised clinical trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2022, 129, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2024: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkel, A.; Bongers, B.; van Kamp, M.; et al. The effects of prehabilitation versus usual care to reduce postoperative complications in high-risk patients with colorectal cancer or dysplasia scheduled for elective colorectal resection: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterology 2018, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, J.F.; Simonsen, C.; Banck-Petersen, A.; et al. . Safety and feasibility of preoperative exercise training during neoadjuvant treatment before surgery for adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction. BJS Open 2019, 3, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarelo, A.; Mota, M.; Amarelo, B.; Ferreira, M.C.; Fernandes, C.S. Technological Resources for Physical Rehabilitation in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Martinez, M.; Carli, F. Prehabilitation: Who can benefit? European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2024, 50, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelo, J.; Phillips, A.W.; Greystoke, A.; et al. . A feasibility trial of prehabilitation before oesophagogastric cancer surgery using a multi-component home-based exercise programme: the ChemoFit study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2022, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Zhou, J.; Norris, M.K.; et al. . Prehabilitative Exercise for the Enhancement of Physical, Psychosocial, and Biological Outcomes Among Patients Diagnosed with Cancer. Current Oncology Reports 2020, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, A.; Gremeaux, V.; Muff, G.; Pache, B.; Geinoz, S.; Larcinese, A.; Benaim, C.; Kayser, B.; Demartines, N.; Hübner, M.; et al. Short term high-intensity interval training in patients scheduled for major abdominal surgery increases aerobic fitness. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 2022, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, D.; Young, J.; Riedel, B.; Morton, R.; Denehy, L.; Heriot, A.; Koh, C.; Li, Q.; Bauman, A.; Sandroussi, C.; et al. Prehabilitation with Preoperative Exercise and Education for Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Cancer Surgery: Protocol for a Multicenter Randomized Controlled TRIAL (PRIORITY TRIAL). BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberan-Garcia, A.; Cano, I.; Bongers, B.C.; Seyfried, S.; Ganslandt, T.; Herrle, F.; Martínez-Pallí, G. Digital support to multimodal community-based prehabilitation: looking for optimization of health value generation. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 662013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, W.P.; Michalski, M.G.; Lee, C.P.; Fickera, G.A.; Chun, S.S.; Eng, S.E.; Liu, L.Y.; Tsai, B.L.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Lavery, J.A.; et al. A digital, decentralized trial of exercise therapy in patients with cancer. NPJ digital medicine 2024, 7, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, R.F.; Bongers, B.C.; Vogelaar, F.J.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L. Feasibility of a Tele-prehabilitation Program in High-risk Patients with Colon or Rectal Cancer Undergoing Elective Surgery: A Feasibility Study. Perioperative Medicine 2022, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloß, K.; Verket, M.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Marx, N.; Schuett, K.; Jost, E.; Crysandt, M.; Beier, F.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Kobbe, G.; et al. Application of Wearables for Remote Monitoring of Oncology Patients: A Scoping Review. Digital Health 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, G.; Schrack, J.; Gresham, L.M.; Shinde, A.M.; Hendifar, A.E.; Tuli, R.; Rimel, B.; Figlin, R.; Meinert, C.L.; Piantadosi, S. Wearable Activity Monitors in Oncology Trials: Current Use of Emerging Technology. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2017, 64, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, E.; Sutton, P.; Rahman, S.; Allen, J.; Saxton, J.; Aziz, O. Prehabilitation with Wearables versus Standard of Care before Major Abdominal Cancer Surgery: A Randomised Controlled Pilot Study (Trial Registration: NCT04047524). Surgical Endoscopy 2022, 36, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naime, K.; Al-Anbuky, A.; Mawston, G. IoT Based Pre-Operative Prehabilitation Program Monitoring Model: Implementation and Preliminary Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (IBIOMED); 2022; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Al-Anbuky, A. IoT-Based Patient Movement Monitoring: The Post-Operative Hip Fracture Rehabilitation Model. Future Internet 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naime, K.; Al-Anbuky, A.; Mawston, G. Remote Monitoring Model for the Preoperative Prehabilitation Program of Patients Requiring Abdominal Surgery. Future Internet 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Al-Anbuky, A.; McNair, P. Activity Classification Feasibility Using Wearables: Considerations for Hip Fracture. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. , Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Tao, F.; Hu, T.; Anwer, N.; Liu, A.; Wei, Y.; Wang, L.; Nee, A. Enabling technologies and tools for digital twin. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 58, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fang, S.; Dong, H.; Xu, C. Review of digital twin about concepts, technologies, and industrial applications. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 58, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elayan, H.; Aloqaily, M.; Guizani, M. Digital Twin for Intelligent Context-Aware IoT Healthcare Systems. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 16749–16757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerva, R.; Lee, G.M.; Crespi, N. Digital Twin in the IoT Context: A Survey on Technical Features, Scenarios, and Architectural Models. Proceedings of the IEEE 2020, 108, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barricelli, B.R.; Casiraghi, E.; Gliozzo, J.; Petrini, A.; Valtolina, S. Human Digital Twin for Fitness Management. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 26637–26664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.; Saikia, M.J. Digital Twins for Healthcare Using Wearables. Bioengineering 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P.; Osiak, T.; Wilk, J.; Prokopiuk, N.; Leczkowski, B.; Pilat, Z.; Rzymkowski, C. Study on the Applicability of Digital Twins for Home Remote Motor Rehabilitation. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ren, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, R.; Pang, Z.; Deen, M.J. A Novel Cloud-Based Framework for the Elderly Healthcare Services Using Digital Twin. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 49088–49101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; He, T.; Fang, B.; Li, C.; Fridenfalk, M.; Lyu, Z. Artificial Intelligence Empowered Digital Twins for ECG Monitoring in a Smart Home. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Lin, G.; Fang, D.; Tai, Y.; Huang, J. Cyber Resilience in Healthcare Digital Twin on Lung Cancer. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 201900–201913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

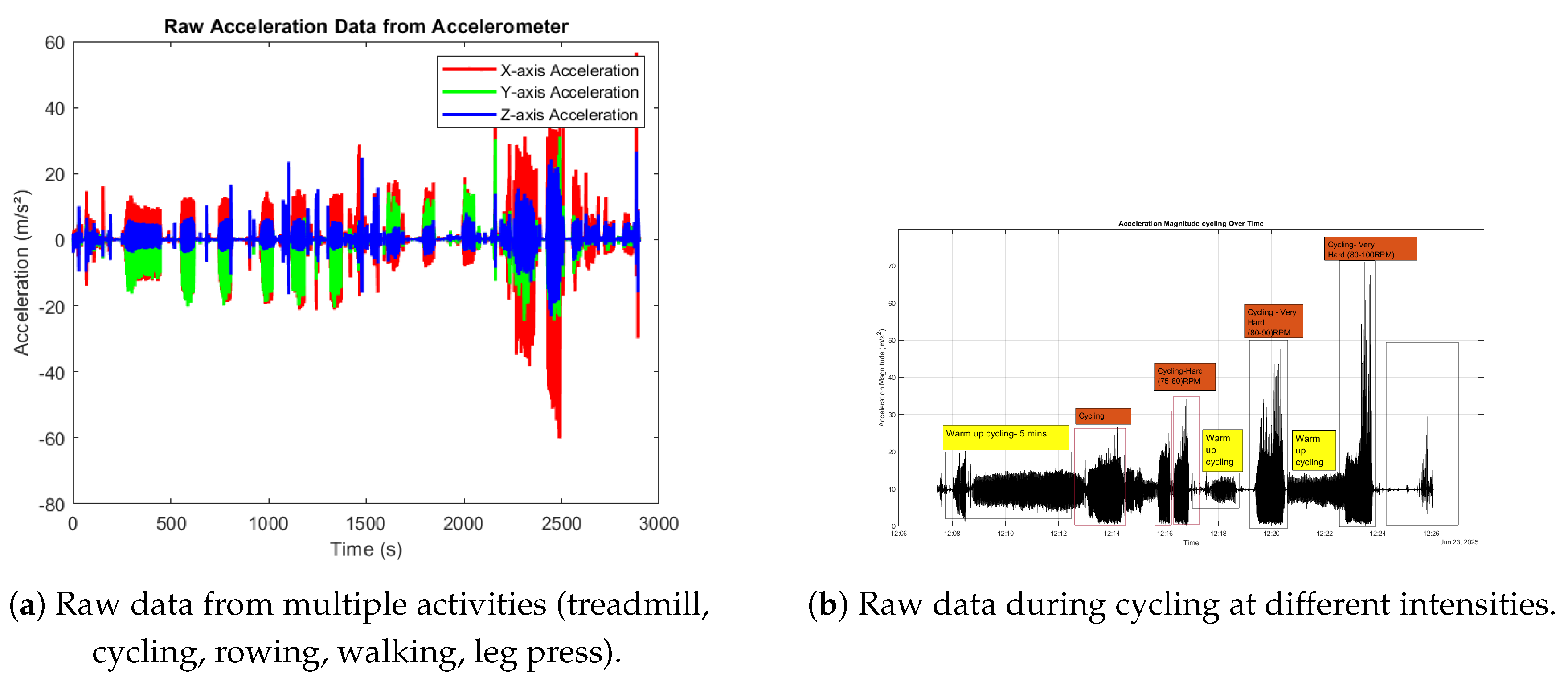

- Parween, G.; Al-Anbuky, A.; Mawston, G.; Lowe, A. Internet of Things-Based Human Movement Monitoring System: Prospect for Conceptual Digital Twin. ASME Journal of Medical Diagnostics 2025, 8, 021104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muka, E.; Marinova, G. Digital Twins to Monitor IoT Devices for Green Transformation of University Campus. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Broadband Communications for Next Generation Networks and Multimedia Applications (CoBCom), July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.E.; Macal, C.M.; Matta, A.; Rabe, M.; Sanchez, S.M.; Shao, G. Enhancing Digital Twins with Advances in Simulation and Artificial Intelligence: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2023 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Dec 2023; pp. 3296–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naime, K.; Al-Anbuky, A.; Mawston, G. Human Movement Monitoring and Analysis for Prehabilitation Process Management. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, E.; Masiak, J.; Mikołajewski, D. Applications of Artificial Intelligence-Based Patient Digital Twins in Decision Support in Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy. Electronics 2024, 13, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Agarwal, A.; Maheshwari, P. A conceptual framework for IoT-based healthcare system using cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference - Cloud System and Big Data Engineering (Confluence); 2016; pp. 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.B.; Xiang, W.; Atkinson, I. Internet of Things for Smart Healthcare: Technologies, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 26521–26544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, F.; Muhammad, G. A Comprehensive Survey of the Internet of Things (IoT) and AI-Based Smart Healthcare. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 3660–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vito, L.; Lamonaca, F.; Mazzilli, G.; Riccio, M.; Luca Carnì, D.; Sciammarella, P.F. An IoT-enabled multi-sensor multi-user system for human motion measurements. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), May 2017; pp. 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhao, L.; Wu, Y. An IoT and machine learning enhanced framework for real-time digital human modeling and motion simulation. Computer Communications 2023, 212, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateef, R.A.; Abbas, A.R. Human Activity Recognition Using Smartwatch and Smartphone: A Review on Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Iraqi Journal of Science 2022, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, D.; Biswas, S. Smartphone based human activity monitoring and recognition using ML and DL: a comprehensive survey. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2020, 11, 5433–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.A.; Imaduddin, S.; Prabhat, R.; Wajid, M. Classification of human motion activities using mobile phone sensors and deep learning model. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India. IEEE, Vol. 1; 2022; pp. 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.U. AI-Fairness Towards Activity Recognition of Older Adults. In Proceedings of the MobiQuitous 2020 - 17th EAI International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems: Computing, Networking and Services, New York, NY, USA, 2021; MobiQuitous ’20; pp. 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebin, T.; Scully, P.J.; Peek, N.; Casson, A.J.; Ozanyan, K.B. Design and Implementation of a Convolutional Neural Network on an Edge Computing Smartphone for Human Activity Recognition. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 133509–133520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracucci, A. Designing Digital Twin with IoT and AI in Warehouse to Support Optimization and Safety in Engineer-to-Order Manufacturing Process for Prefabricated Building Products. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A.R.; Gupta, R.; Zaman Batool, T.; Landolsi, T.; Aloul, F.; Al Nabulsi, A. Digital Twin Conceptual Model within the Context of Internet of Things. Future Internet 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, G.J.; Hashmi, M.F.; Gupta, A. Surface Electromyography and Artificial Intelligence for Human Activity Recognition—A Systematic Review on Methods, Emerging Trends Applications, Challenges, and Future Implementation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 105140–105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukor, A.S.A.; Zakaria, A.; Rahim, N.A. Activity recognition using accelerometer sensor and machine learning classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 14th International Colloquium on Signal Processing and Its Applications (CSPA); 2018; pp. 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Review Study | Population | Duration | Type of Exercises | Key Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Prehabilitation | ||||

| [2,3] | Colorectal cancer patients | 4–6 weeks | Aerobic and resistance training, flexibility exercise | 20% increase in 6MWT; 35% reduction in postoperative complications |

| [7] | 62 candidates (patients) | 17.5 sessions (2 sessions/week) | High, moderate intensity | aerobic fitness improvement, strength, and quality of life; lower risk of surgical failure in exercise group (5% vs. 21%) |

| [11] | Review study | — | Low, medium, and high intensity exercises | Significant improvements in physical activity scores and walking test results, indicating better physical readiness for surgery |

| [12] | 14 patients | 3 sessions/week for 3 weeks | Low-volume HIIT program | 13% increase in peak; strong correlation between walking distance and peak (, ) |

| Unsupervised / Technology-Based Prehabilitation | ||||

| [13] | 172 participants | 4–8 weeks | Aerobics, resistance, and respiratory exercises; recommendations of home exercises | Improved physical and psychological readiness for surgery; potentially improving postoperative outcomes |

| [4] | 204 randomized patients (out of 543 assessed) | 5 weeks | Home-based walking | No significant improvement in functional recovery or other outcomes compared to standard care |

| [8] | 80 patients scheduled for colorectal cancer resection | — | — | 20 m improvement in 6MWT; postoperative complications assessed |

| [14,15,16,17] | Abdominal cancer patients | 4–6 weeks | Low to high cardiorespiratory fitness testing using treadmill | Adherence and outcomes of prehabilitation assessed |

| [20,22,38] | Abdominal cancer patients | 4–6 weeks | Low, medium, high aerobic exercises | Remote monitoring and feedback alert system applied |

| Sl.No | Prehabilitation Elements | Boundaries | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prehabilitation Program Duration | 4–6 weeks / 4–8 weeks | Patient’s status and surgical schedules |

| 2 | Number of sessions per week | 2 or more | Can participate as per the guidance of health supervisor |

| 3 | Threshold duration | 150 minutes of moderate duration or equivalent | 75 minutes of vigorous intensity or a combination of vigorous and moderate exercise |

| 4 | Minimum Duration of Each Session | 10 minutes or more at moderate intensity | As per patients’ needs |

| 5 | Initial Assessment | 6MWT, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, 10-m shuttle walk test | Dependent upon clinical resources and expertise |

| 6 | Exercises Involved | Walking, cycling, treadmill and land-based running, cross-trainer, staircase ascending & descending, rowing, step-up, leg press | Can be altered according to need |

| 7 | Location | Healthcare center, clinic, gym, indoor, sports club or park | Availability of resources |

| 8 | Performance Measurement | Credit Point Calculation | Not standardized; conceptual analysis of performance based on credit point calculation |

| Study | Technology Used | Application | Performance/Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

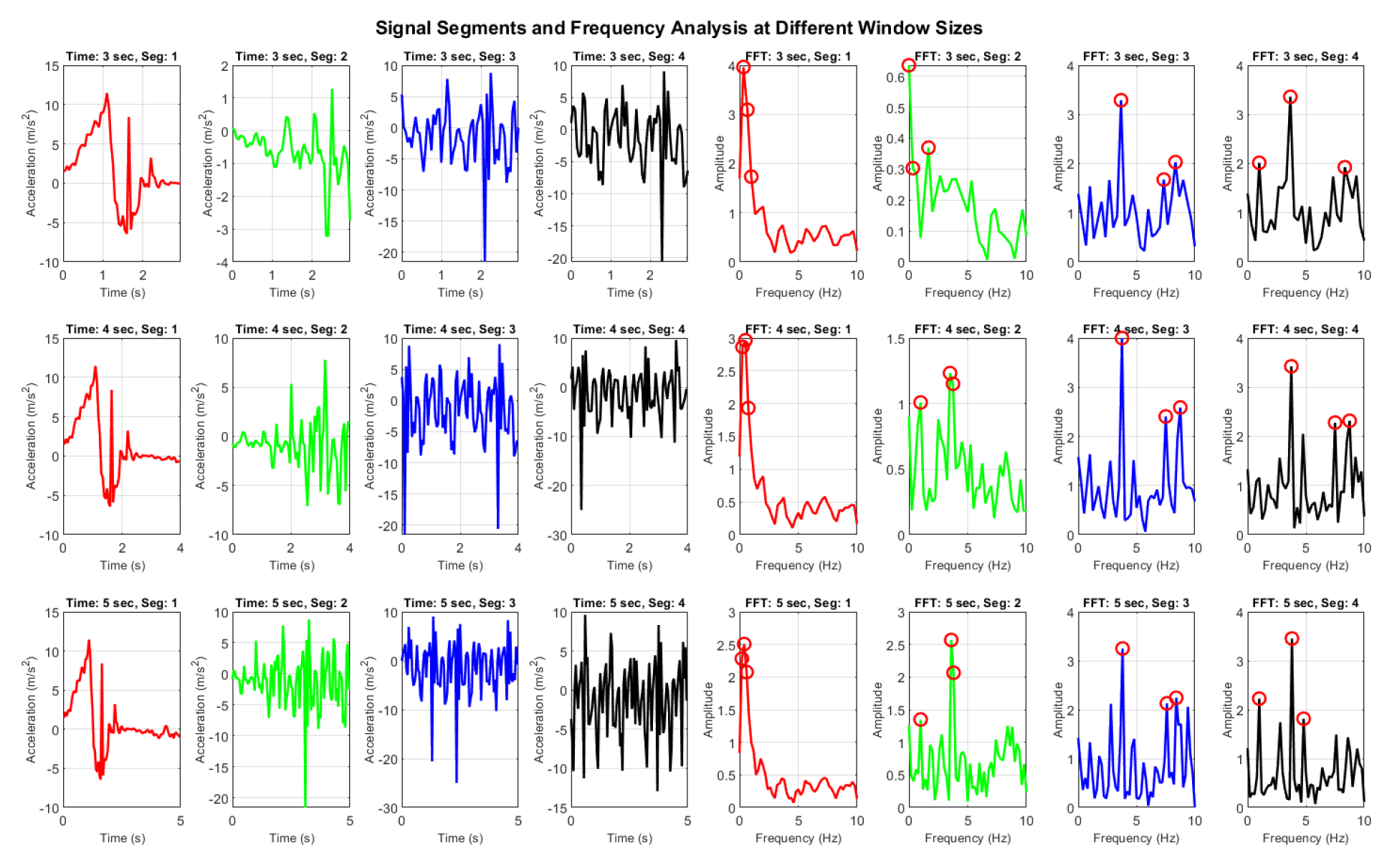

| [20,23] | Accelerometer, IMU, IoT-enabled devices | Lower body and transitional activities | Frequency domain analysis (FFT), 4-sec window size for processing; achieved 78% accuracy |

| [47] | Smart mobile sensors (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer), machine learning | Walking, brisk walking | Deep learning model reached 96.5% accuracy |

| [45] | Smartphone embedded sensors with classifier | Daily activities (standing, sitting, lying, stairs up/down, walking) | FFT and ML with 3-sec window size, PCA – 96.11% accuracy; Frequency domain analysis – 92.10% accuracy |

| [46] | Smartphone with ML and deep learning | Static and dynamic activities | Model performance not reported |

| [49] | Waist-mounted inertial sensor (accelerometer and gyroscope) | Real-time data: walking, upstairs, downstairs, sitting, standing, lying | Adaptive window size; 96.4% accuracy in five-class static and dynamic activity recognition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).