Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Assess the current state of water resources in Pakistan, considering factors such as availability, distribution, and quality in the context of rapidly changing climatic conditions.

- Analyze the impacts of climate change on Pakistan’s water security, including changes in precipitation patterns, glacial melting, and changes in the river flows.

- Identify the vulnerabilities and challenges posed by climate change on urbanization and water dependent sectors such as agriculture, industry, and human settlements.

- Propose policy recommendations and climate and adaptation strategies for efficient water management on a sustainable basis.

- Achieve UNSDG 6 and 13 by 2030.

2. Literature Review

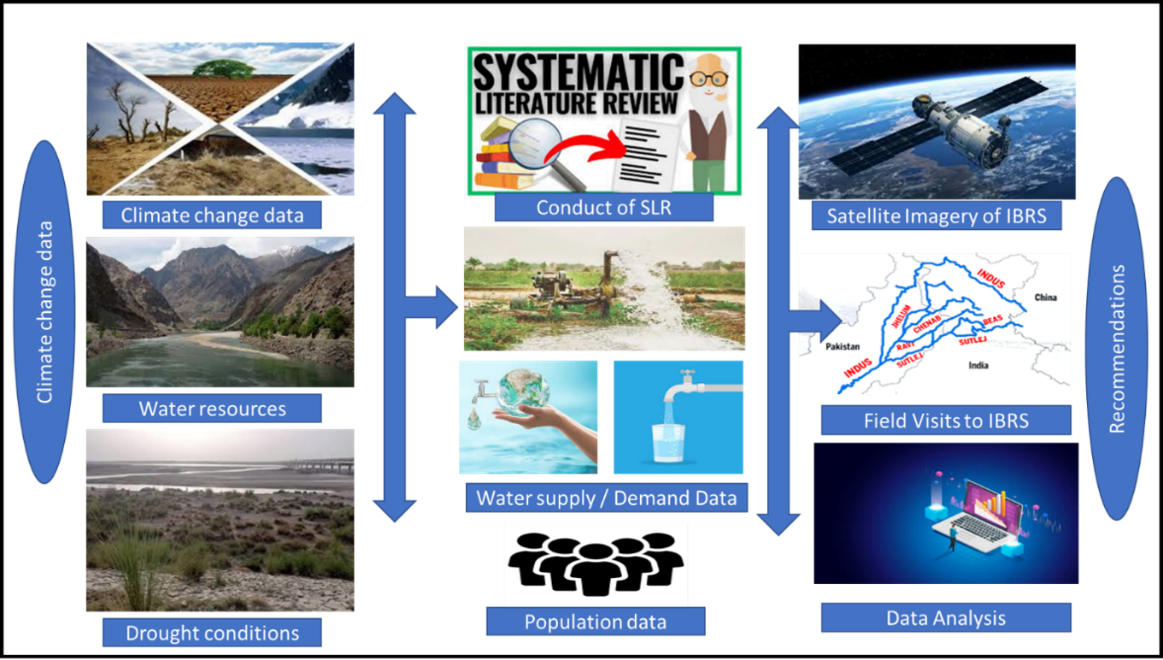

3. Materials and Methods

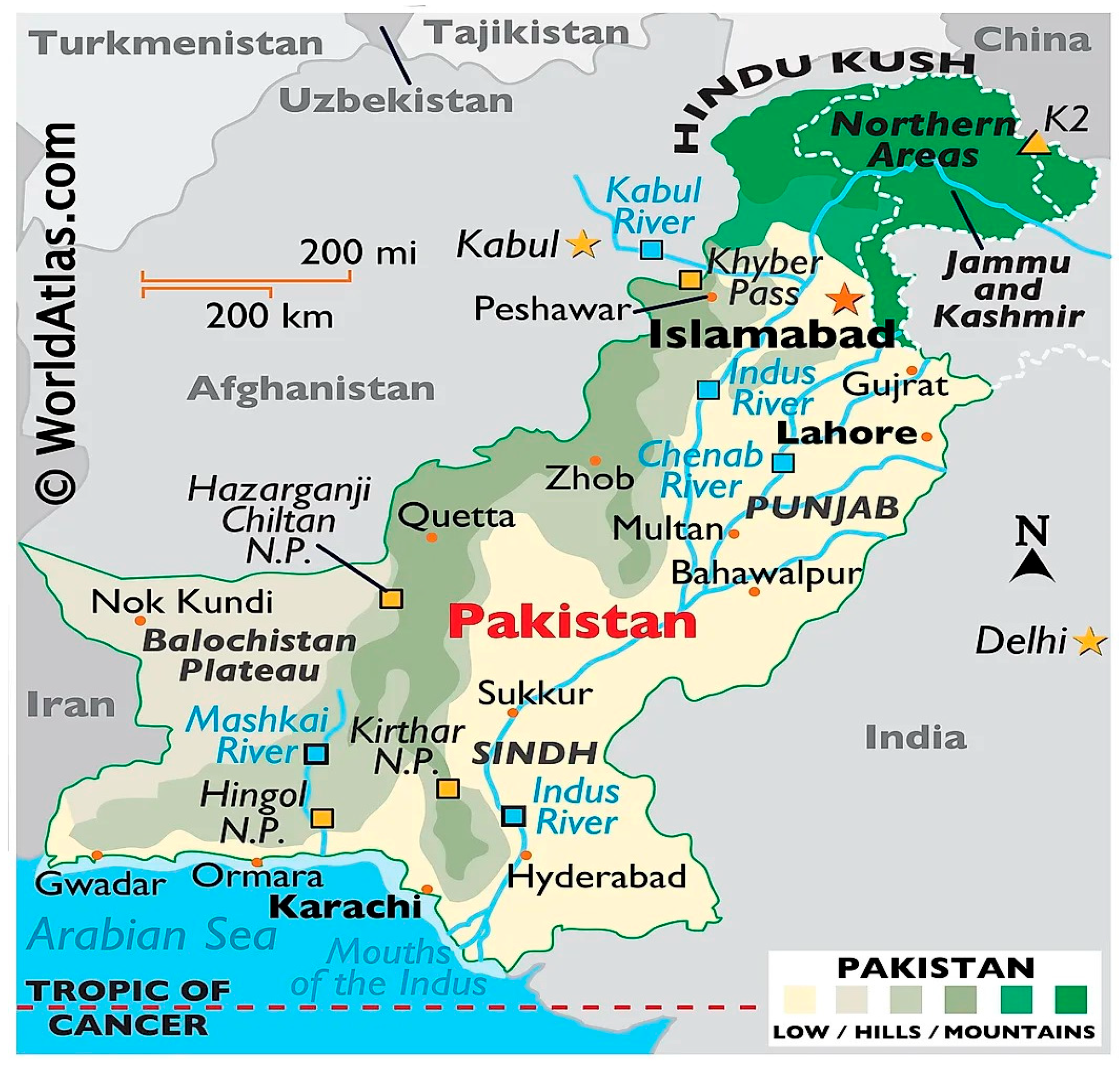

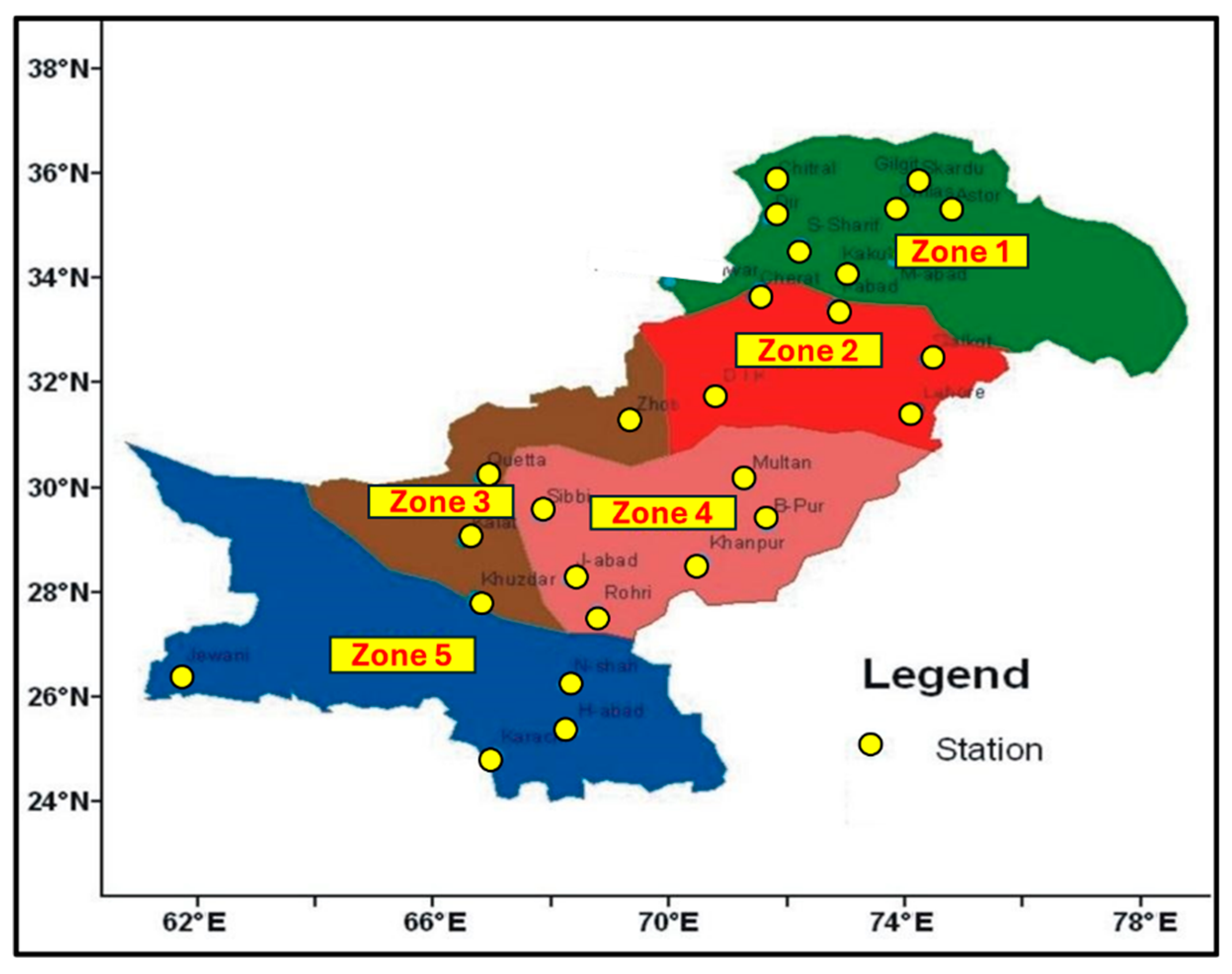

3.1. Introducing Geographical Regions of Pakistan

3.2. Climatic Conditions

3.3. Study Area and Model Setting

3.4. Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

3.5. Data Investigation Including Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

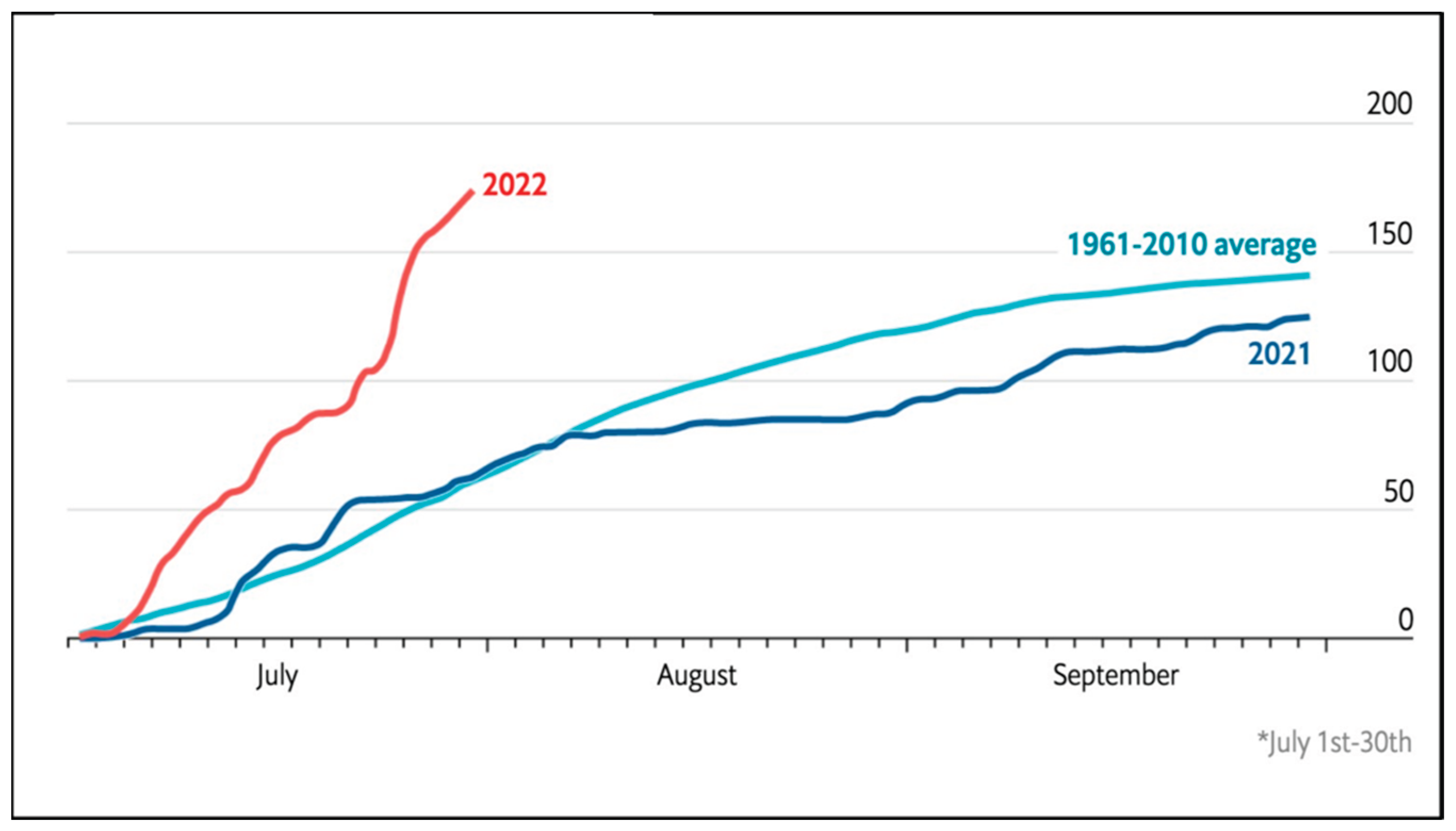

4.1. Climate Change Vulnerbalities

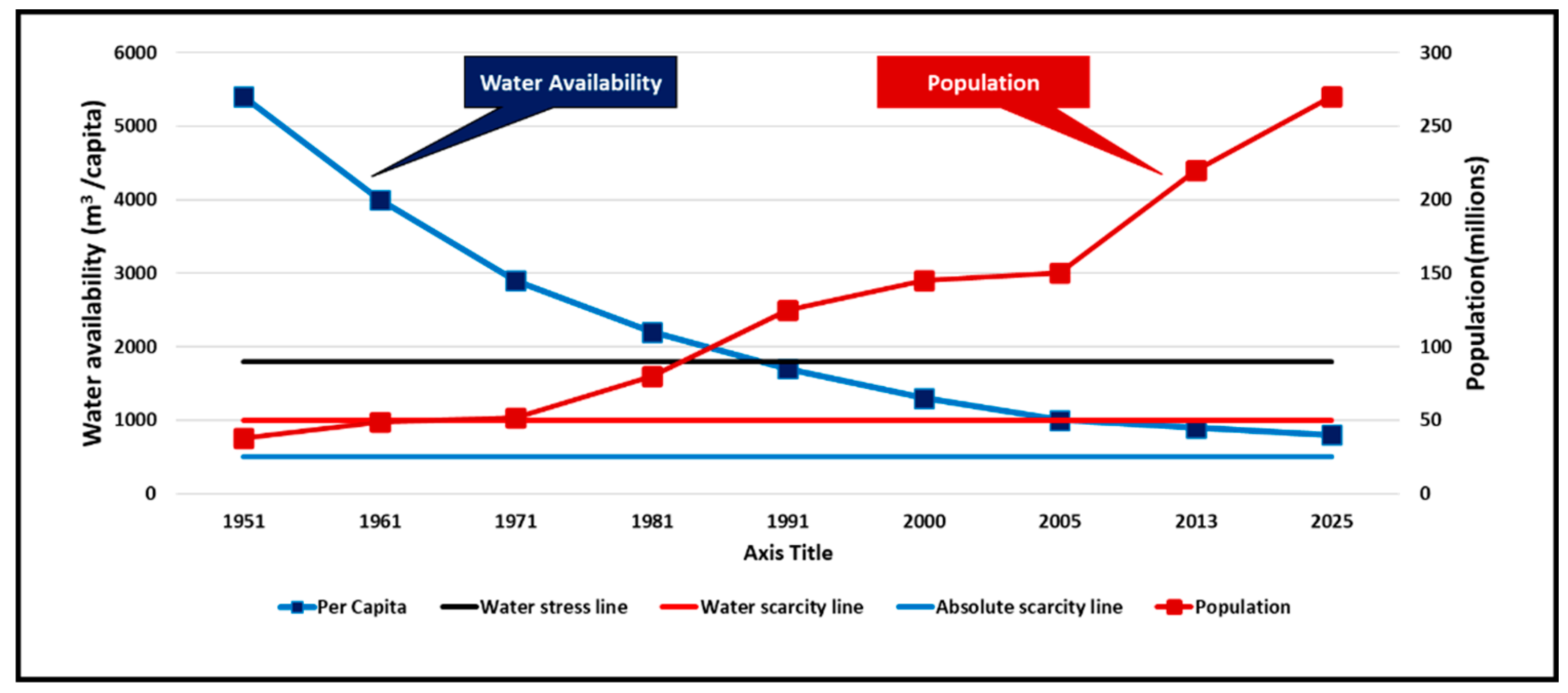

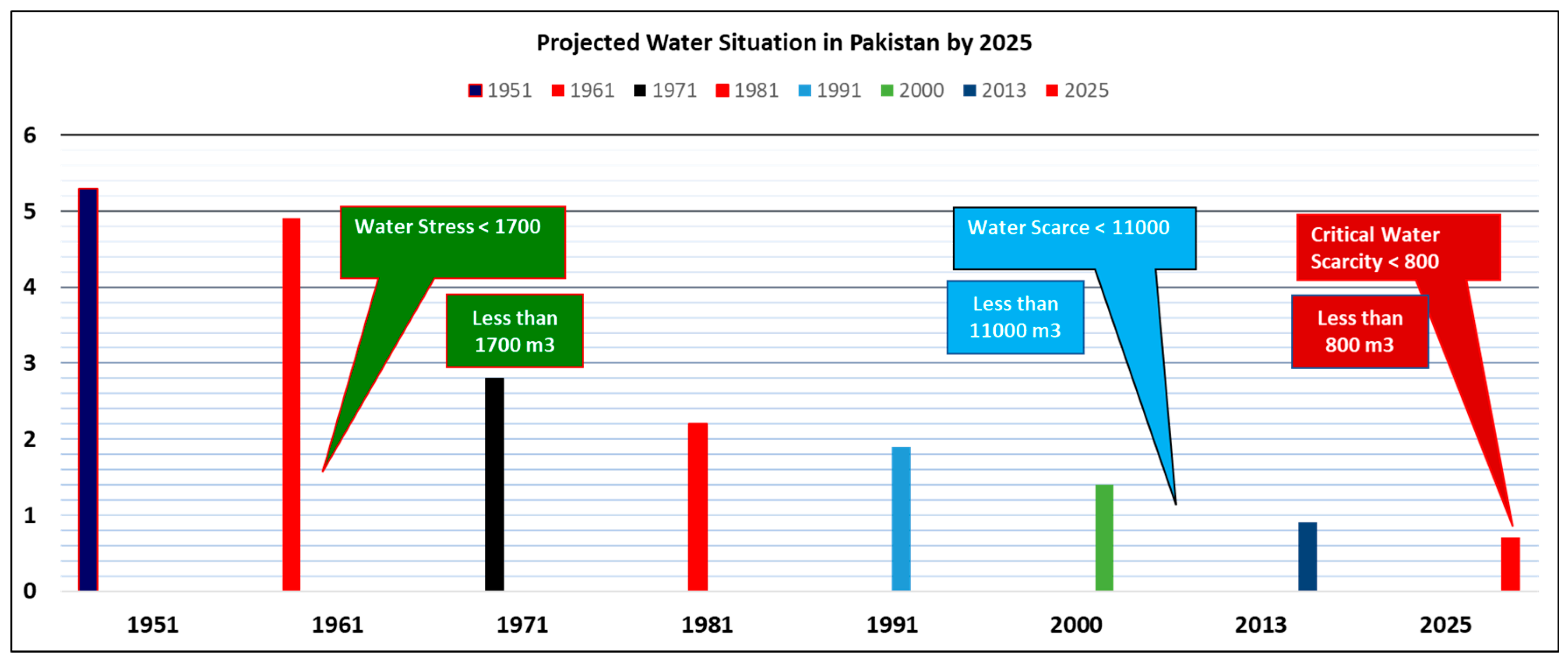

4.2. Water Resources Distribution

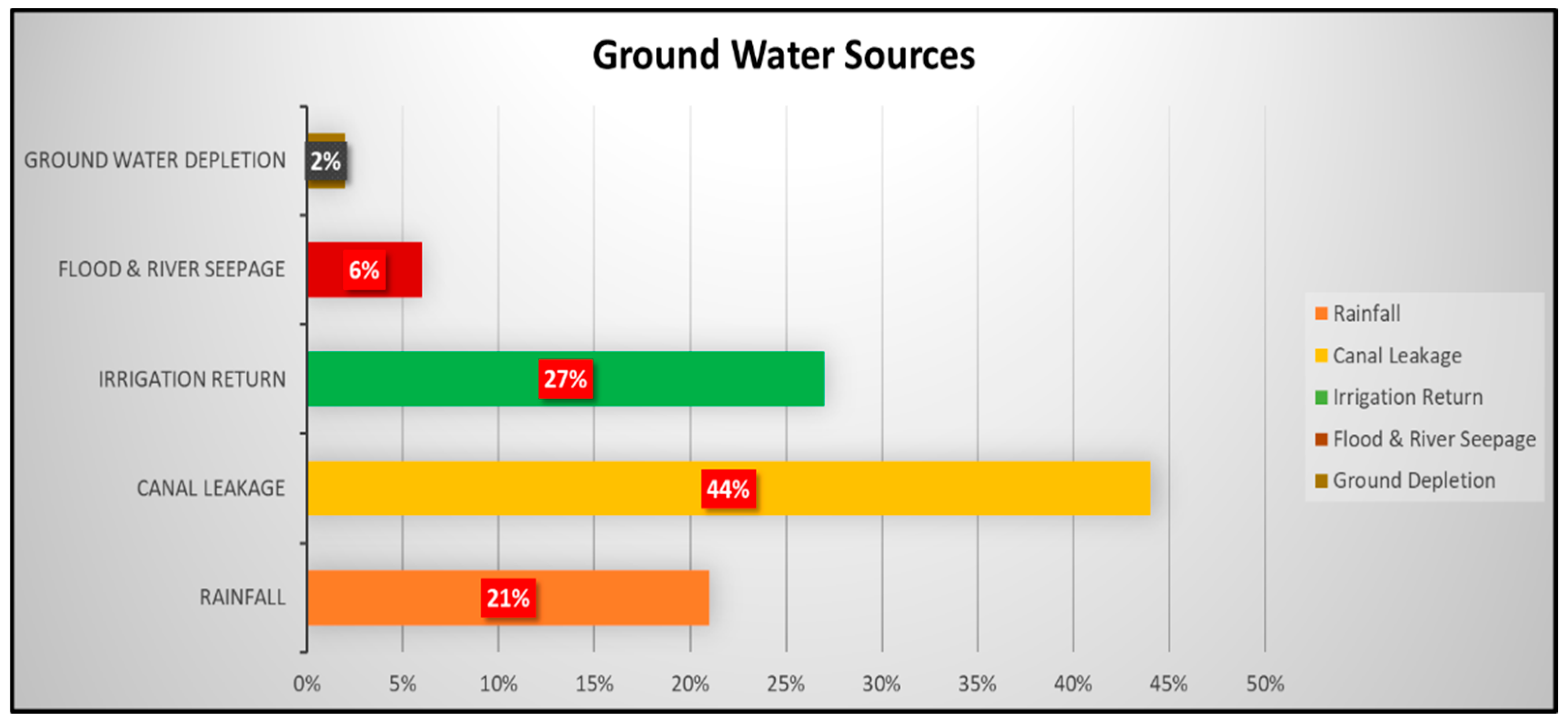

4.3. Sources of Water Supply in Pakistan

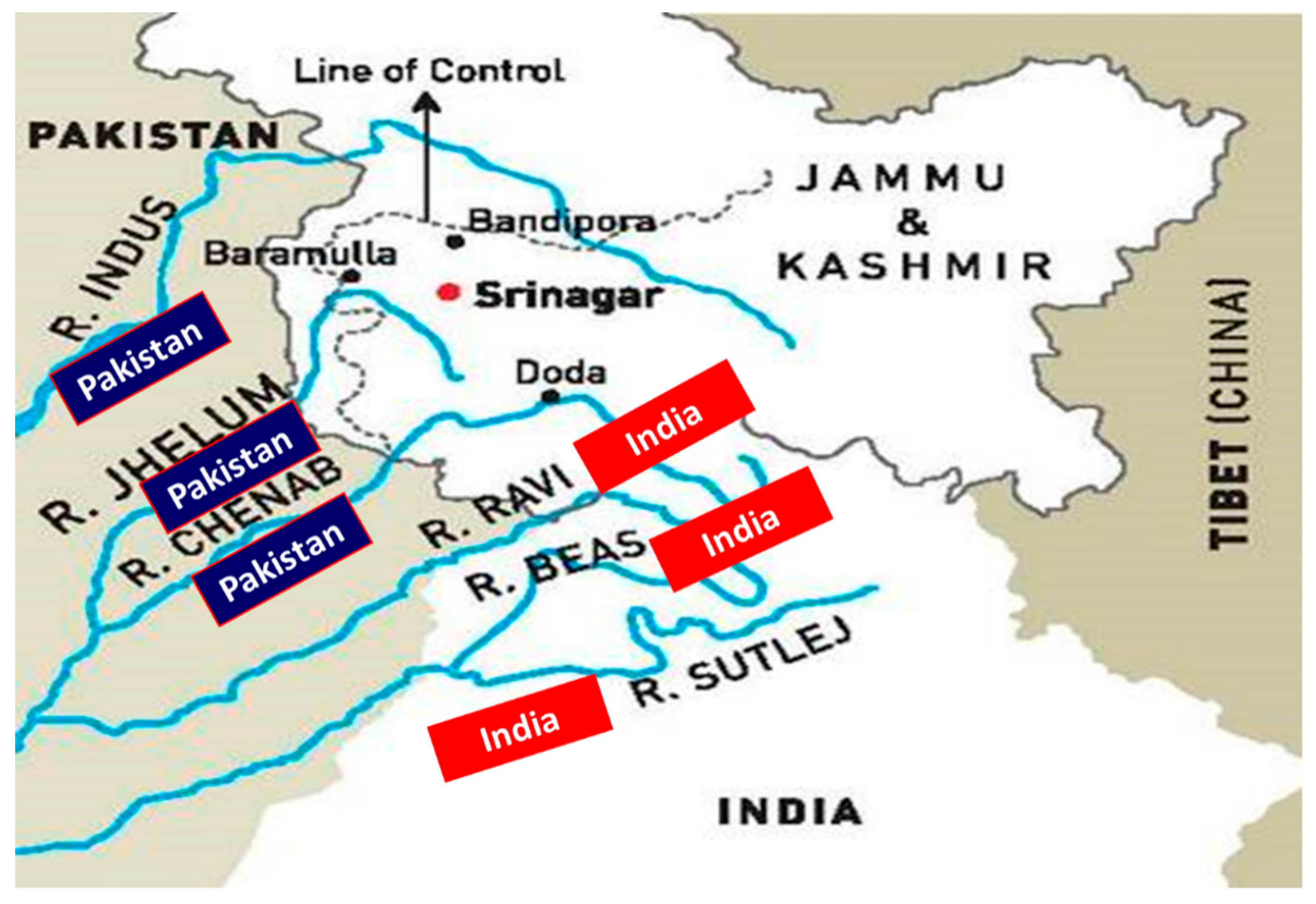

4.4. Water Reservoirs and Transboundry Water Sharing with India

4.5. Sustainable Water Management

4.6. Inadequate Recycling of Waste Water for Agricultural Purposes

4.7. Unplanned Transformative Urbanization

5. Policy Recommendations

5.1. Water Management and Sustainable Development

5.2. Alternatives and Distributions of Agricultural Water Resources

5.3. Construction of New Wtaer Resorvoirs on Urgent Basis as a National Priority

5.4. Preserving Precious Ground Water Resources

5.5. Stringent Regulatory Framework to Check Urbanization

Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Committee Approval

References

- Waseem, Ishaque; et al. , Climate Change and Water Crises in Pakistan: Implications on Water Quality and Health Risks. Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2022, 2022, 5484561. [Google Scholar]

- Jumaina Siddiqui, Pakistan’s Climate Challenges Pose a National Security Emergency. United States Institute of Peace, July 7, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/07/pakistans-climate-challenges-pose-national-security-emergency.

- Zaira, Manzoor; et al. , Floods and Flood Management and Its Socio-Economic Impact on Pakistan: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 2480. [Google Scholar]

- G. Rasul, Implications of Climate Change for Pakistan. Proceedings of AASSA—PAS Regional Workshop on Challenges in Water Security to Meet the Growing Food Requirement.

- Muhammad Umar, Munir; et al. Water Scarcity Threats to National Food Security of Pakistan—Issues, Implications, and Way Forward. Emerging Challenges to Food Production and Security in Asia, Middle East, and Africa: Climate Risks and Resource Scarcity, Springer, 2021, 241–66.

- Shaukat, Ali; et al. , 21st Century Precipitation and Monsoonal Shift over Pakistan and Upper Indus Basin (UIB) Using High-Resolution Projections. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 797, 149139. [Google Scholar]

- S. M. A. Shah and M. F. Ahmad, Minimum Temperature Analysis and Trends in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Meteorology 13, no. 26 (2017).

- M. R Bhutiyani, Vishawas S. Kale, and N. J. Pawar, Climate Change and the Precipitation Variations in the Northwestern Himalaya: 1866–2006. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2010, 30, 535–48. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Fowler and D. R. Archer, Conflicting Signals of Climatic Change in the Upper Indus Basin. Journal of Climate 2006, 19, 4276–93. [CrossRef]

- Shumaila Andleeb, Nature-Based Solutions, Civic Sense on Water Conservation Crucial to Address Pakistan’s Water Scarcity: President. National, Associated Press of Pakistan (Islamabad), November 28, 2023.

- Saiqa Imran, Lubna Naheed Bukhari, and Samar Gul, Water Quality Assessment Report along the Banks of River Kabul Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). Water report (Pakistan Council of Research on Water Resources (PCWR), March 1, 2018), chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pakistan-Council-Of-Research-In-Water-Resources-Islamabad/publication/ 360256080 _Water_Quality_Assessment_ Report_ Along_ the_Banks_of_River_Kabul_Khyber_Pakhtunkhwa/links/626b8967d99ac24cc472be1b/Water-Quality-Assessment-Report-Along-the-Banks-of-River-Kabul-Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.pdf.

- Abdul Ghani, Soomro; et al. , Cascade Reservoirs: An Exploration of Spatial Runoff Storage Sites for Water Harvesting and Mitigation of Climate Change Impacts, Using an Integrated Approach of GIS and Hydrological Modeling. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13538. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Damkjaer and Richard Taylor, The Measurement of Water Scarcity: Defining a Meaningful Indicator. Ambio 2017, 46, 513–31. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Sibtain; et al. , Hydropower Exploitation for Pakistan’s Sustainable Development: A SWOT Analysis Considering Current Situation, Challenges, and Prospects. Energy Strategy Reviews 2021, 38, 100728. [Google Scholar]

- Awais Piracha and Zahid Majeed, Water Use in Pakistan’s Agricultural Sector: Water Conservation under the Changed Climatic Conditions. International Journal of Water Resources and Arid Environments 2011, 1, 170–79.

- Muhammad Umar, Munir; et al. Water Scarcity Threats to National Food Security of Pakistan—Issues, Implications, and Way Forward. Emerging Challenges to Food Production and Security in Asia, Middle East, and Africa: Climate Risks and Resource Scarcity, Springer, 2021, 241–66.

- Muhammad Zia Ur, Rehman; et al. , Emerging Dynamics and National Security of Pakistan: Challenges and Strategies. Research Consortium Archive 2025, 3, 228–40. [Google Scholar]

- Waseem Ishaque and Saima Shaikh, WATER AND ENERGY SECURITY FOR PAKISTAN A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS.. Grassroots (17260396) 51, no. 1 (2017).

- Suhaib Bin, Farhan; et al. , Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change on the High Altitude Snow-and Glacier-Fed Hydrological Regimes of Astore and Hunza, the Sub-Catchments of Upper Indus Basin. Journal of Water and Climate Change 2020, 11, 479–90. [Google Scholar]

- Areeja, Syed; et al. , Climate Impacts on the Agricultural Sector of Pakistan: Risks and Solutions. Environmental Challenges 2022, 6, 100433. [Google Scholar]

- Mudassar, Hussain; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Mitigation on Environmental and Natural Calamities in Pakistan. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 192 (2020): 1–20.

- Shujaat Abbas, Climate Change and Major Crop Production: Evidence from Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 5406–14. [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, Ahmad; et al. Water Resources and Their Management in Pakistan: A Critical Analysis on Challenges and Implications. Water-Energy Nexus, Elsevier, 2023.

- Els, Bekaert; et al. , Domestic and International Migration Intentions in Response to Environmental Stress: A Global Cross-Country Analysis. Journal of Demographic Economics 2021, 87, 383–436. [Google Scholar]

- Waseem Ishaque and Muhammad Zia ur Rehman, Impact of Climate Change on Water Quality and Sustainability in Baluchistan: Pakistan’s Challenges in Meeting United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (UNSDG) Number 6. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2553. [CrossRef]

- Waseem Ishaque and Khalid Sultan, Water Management and Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Environmental and Health Impacts of Water Quality on Achieving the UNSDGs by 2030. Frontiers in Water 2024, 6, 1267164. [CrossRef]

- Hafiz Qaisar, Yasin; et al. Climate-Water Governance: A Systematic Analysis of the Water Sector Resilience and Adaptation to Combat Climate Change in Pakistan. Water Policy 23, no. 1 (2021): 1–35.

- Tariq, Ali; et al. , Sustainable Water Use for International Agricultural Trade: The Case of Pakistan. Water 2019, 11, 2259. [Google Scholar]

- Asad Sarwar, Qureshi; et al. , Challenges and Prospects of Sustainable Groundwater Management in the Indus Basin, Pakistan. Water Resources Management 2010, 24, 1551–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, A. Mojid and Mohammed Mainuddin, Water-Saving Agricultural Technologies: Regional Hydrology Outcomes and Knowledge Gaps in the Eastern Gangetic Plains—a Review. Water 2021, 13, 636. [Google Scholar]

- Waseem, Ishaque; et al. Pakistan’s Water Resource Management: Ensuring Water Security for Sustainable Development. Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (2023), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1096747.

- Mubashar Rizvi, Can the Indus Waters Treaty Be Held in Abeyance? What the Law Allows. Stimson Center, South Asian Voices, /: 2025, https, 9 May 2025.

- Hasan, H. Karrar and Till Mostowlansky, Assembling Marginality in Northern Pakistan. Political Geography 2018, 63, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Safdar, Sidra; et al. , Seasonal Variation of Fine Particulate Matter in Residential Micro–Environments of Lahore, Pakistan. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2015, 6, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan Ahmad, Baig; et al. Groundwater Markets in the Indus Basin Irrigation System, Pakistan. Water Markets: A Global Assessment, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021, 126.

- Narmeen Taimur, List of Famous Dams in Pakistan. Graana.Com Blog, March 3, 2022, https://www.graana.com/blog/dams-in-pakistan/.

- Fazlullah Akhtar and Usman Shah, Emerging Water Scarcity Issues and Challenges in Afghanistan. Water Issues in Himalayan South Asia: Internal Challenges, Disputes and Transboundary Tensions, Springer, 2020, 1–28.

- Antonio Guterres, ‘Don’t Flood the World Today; Don’t Drown It Tomorrow’, UN Chief Implores Leaders. UN News, September 14, 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1126601.

- David, Eckstein; et al. , Global Climate Risk Index 2021 (German Watch, 2021), 1–50, https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_2.pdf.

- Gregory Pappas, Pakistan and Water: New Pressures on Global Security and Human Health. American Journal of Public Health, 2011; 101, 786–788. [CrossRef]

- Daniya Khalid, Pakistan’s National Water Policy. News, The Express Tribune, July 28, 2017, http://tribune.com.pk/story/1469030/pakistans-national-water-policy.

- Azizullah, Azizullah; et al. Water Pollution in Pakistan and Its Impact on Public Health--a Review. Environment International 37, no. 2 (2011): 479–97. [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, Ahmed; et al. Water Resources and Conservation Strategy of Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review 46, no. 4 (2007): 997–1009.

- Zofeen, T. Ebrahim, Is Pakistan Running out of Fresh Water?. DAWN.COM, March 30, 2018, https://www.dawn.com/news/1398499.

- Saqib, Riaz; et al. Indian Aqua Aggression: Investigating the Impact of Indus Water Treaty (IWT) on Future of India Pakistan Water Disputes. NDU Journal 14, no. XXXIV (2020): 131–46.

- Waseem Ishaque and Saima Shaikh, Water and Energy Security for Pakistan a Retrospective Analysis. Grassroots 51, no. 1 (2017).

- Amit Ranjan, Inter-Provincial Water Sharing Conflicts in Pakistan. Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies 4, no. 2 (2012): 102–22.

- National Water Policy of Pakistan 2018. Ministry of Water Resources, Government of Pakistan, April 2018, https://mowr.gov.pk/SiteImage/Policy/National-Water-Policy.pdf.

- Manzoor et al., Floods and Flood Management and Its Socio-Economic Impact on Pakistan: A Review of the Empirical Literature.

- Michael Kugelman, Pakistan’s Runaway Urbanization: What Can Be Done? (Asia Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2014).

- Asad Sarwar Qureshi, Groundwater Governance in Pakistan: From Colossal Development to Neglected Management. Water, 2020; 12, 11. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Abo ul Hassan Rashid et al., Urbanization and Its Effects on Water Resources: An Exploratory Analysis. Asian Journal of Water, Environment and Pollution 15, no. 1 (2018): 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Tayyab, Sohail; et al. Impacts of Urbanization, LULC, LST, and NDVI Changes on the Static Water Table with Possible Solutions and Water Policy Discussions: A Case from Islamabad, Pakistan. Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz Alvi, CCI Meeting: Centre Stands for Judicious Water Distribution among Provinces, Says PM Imran Khan, (Islamabad), December 24, 2019, https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/587796-cci-meeting-centre-stands-for-judicious-water-distribution-among-provinces-says-pm-imran-khan.

- IRSA, Apportionment of the Waters of Indus River System Between Provinces of Pakistan. March 21, 1991, http://pakirsa.gov.pk/WAA.aspx.

| Description | Values | Zone 1 | Zone 2 | Zone 3 | Zone 4 | Zone 5 |

| Observation points | 12 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 5 | |

| 20 years average | valid/ missing values | 296/4 | 178/6 | 119/5 | 176/7 | 120/1 |

| Mean | Used values | 69.53 | 65.80 | 35.78 | 24.45 | 33. 15 |

| 5% trimmed Mean | 67.43 | 63.67 | 34.53 | 22.34 | 30.73 | |

| Median | 61.13 | 59.05 | 31.40 | 20.20 | 26.00 | |

| Std. Error | 3.71 | 3.70 | 1.28 | 1.05 | 3.30 | |

| 95%CI | Lower Bound | 62.28 | 60.42 | 29.10 | 21.47 | 28.25 |

| Upper Bound | 72.80 | 73.40 | 34.48 | 23.63 | 37.60 | |

| Skewness | 0.40 | 1.10 | 1.28 | 1.05 | 1.36 | |

| F- Value | 1.85 | 0.89 | 3.65 | 1.33 | 5.79 | |

| Sig. | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).