Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Literature Review

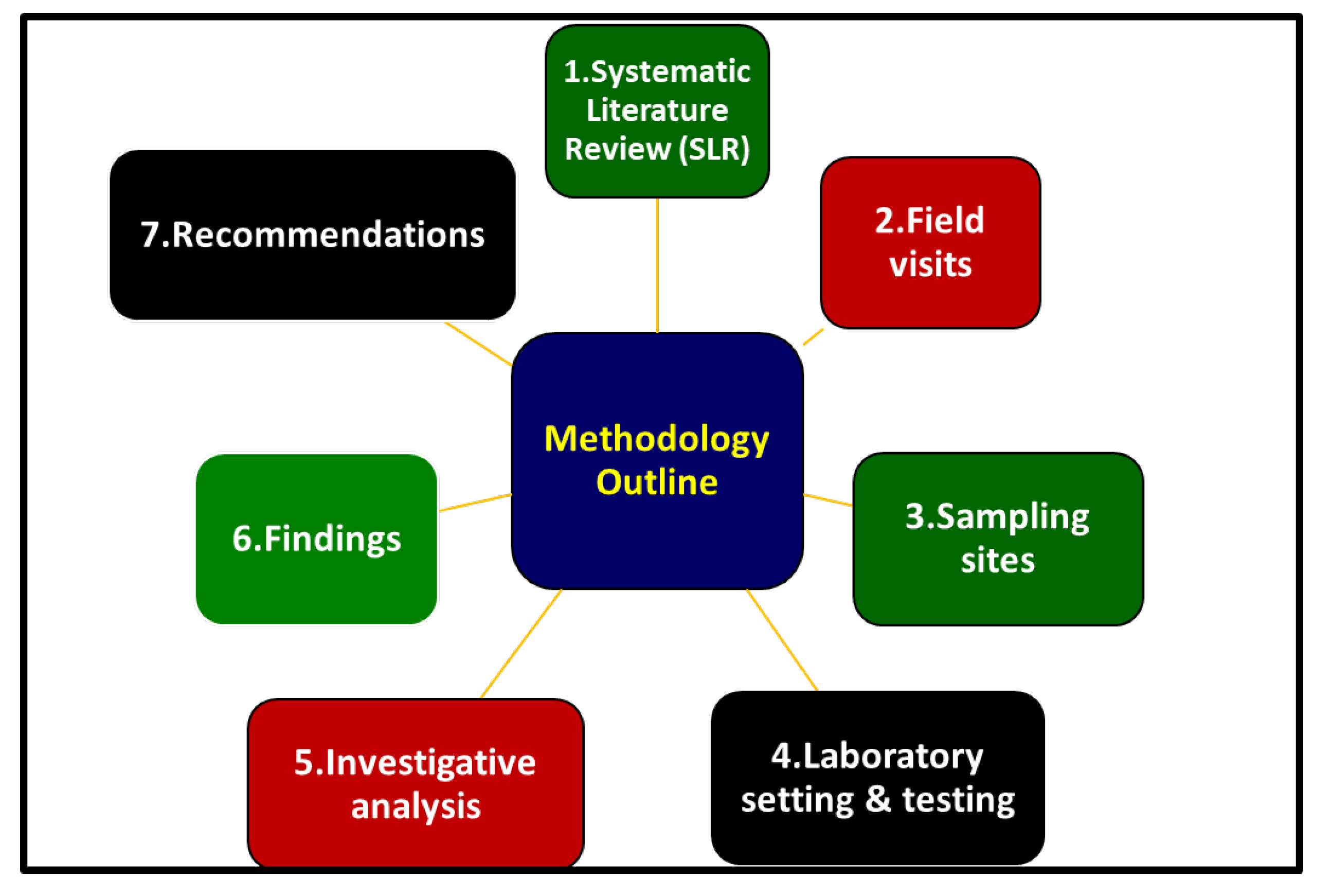

Materials and Methods

3.1. Systematic Literature Review

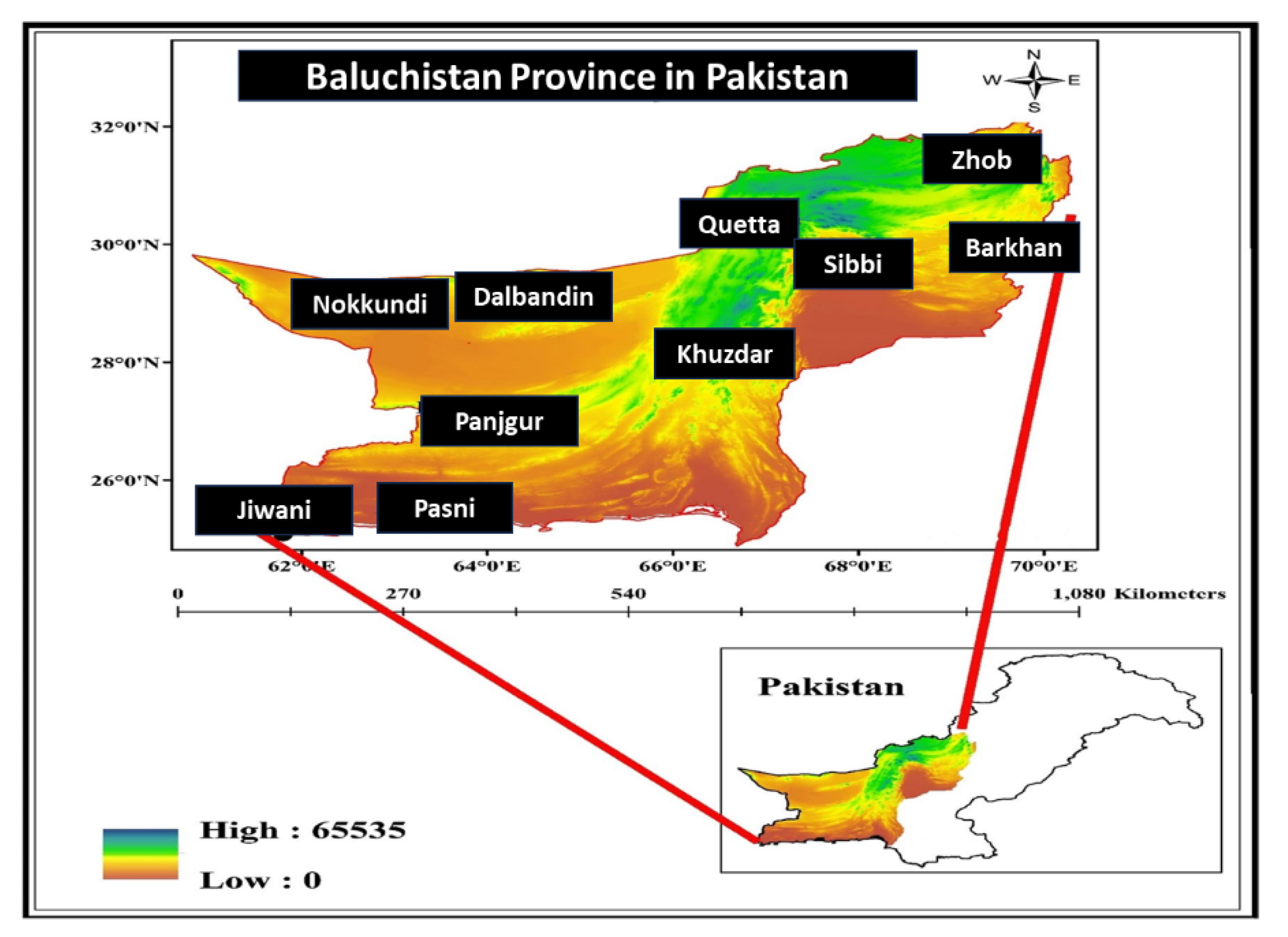

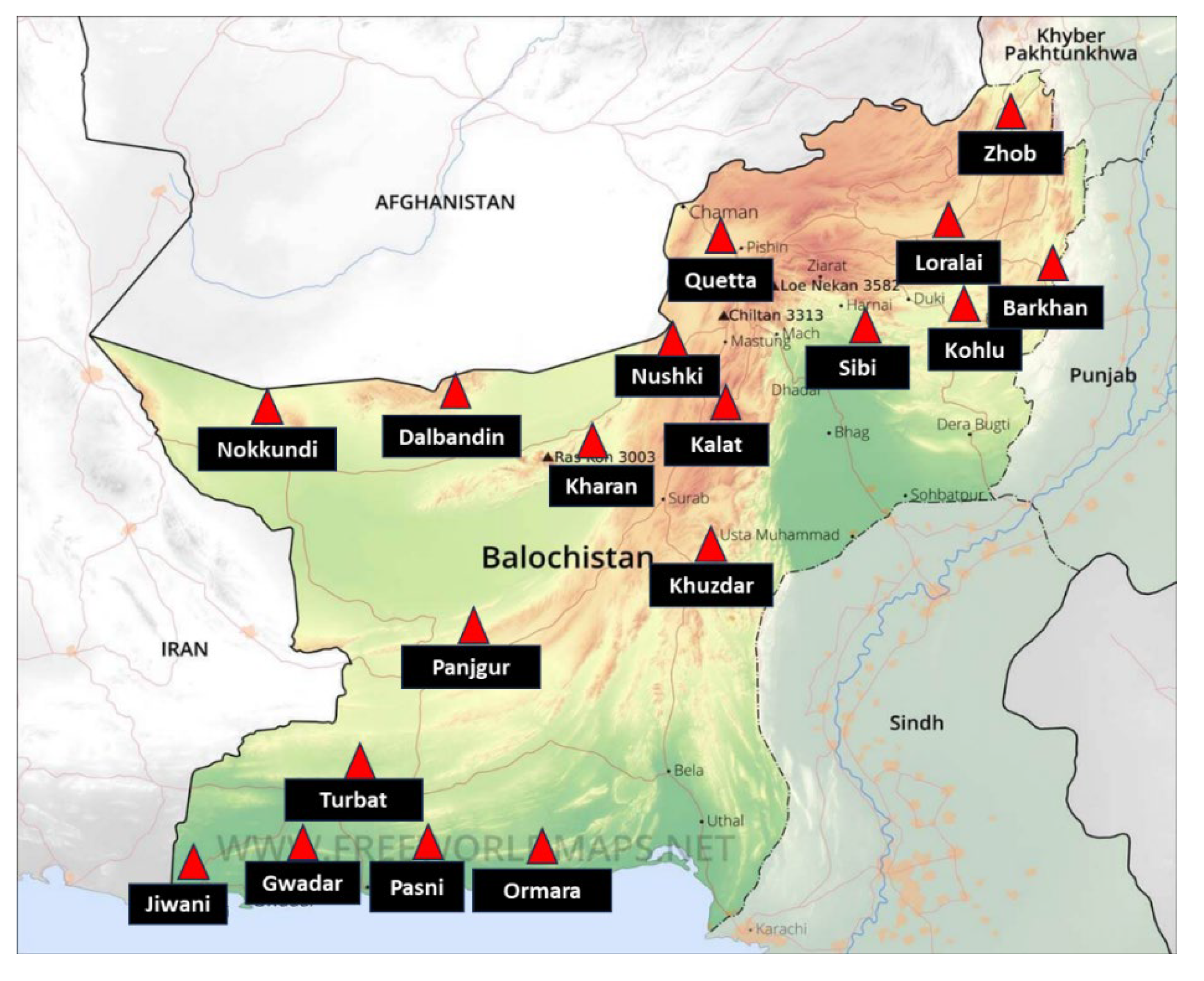

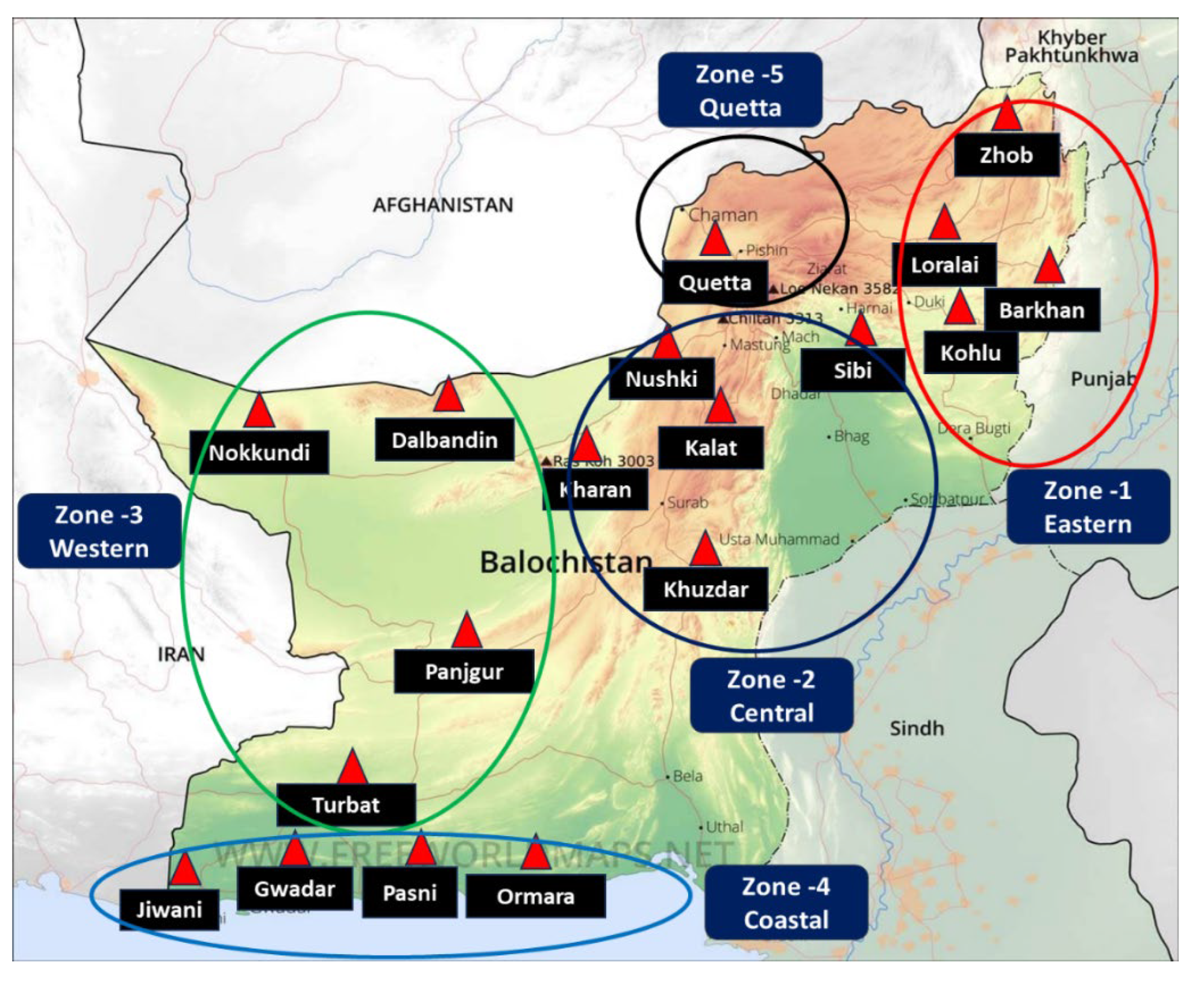

3.2. Study Area

3.3. Water Sampling Sites

3.4. Laboratory Examination and Water Quality Analysis

3.5. Microbiological Examination

3.6. Physical Examination

3.7. Chemical Examination

3.8. Supplementary Factors Considered During Investigation

Results and Discussion

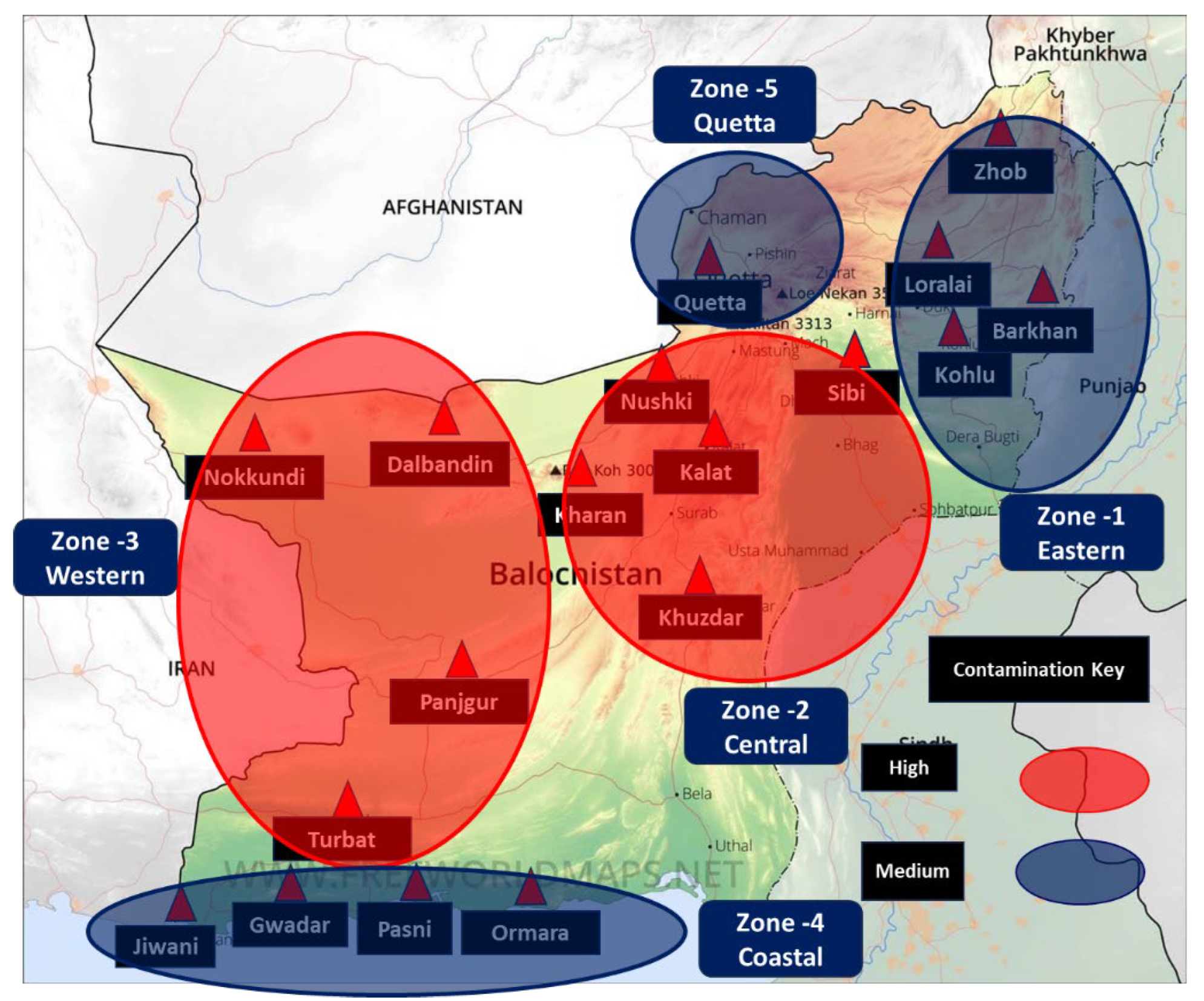

4.1. Zone 1–(Eastern Zone)

4.2. Zone 2 (Central)

4.3. Zone 3 (Western)

4.4. Zone 4 (Coastal)

4.5. Zone 5 (Quetta)

4.6. Causes of Water Contamination in Baluchistan

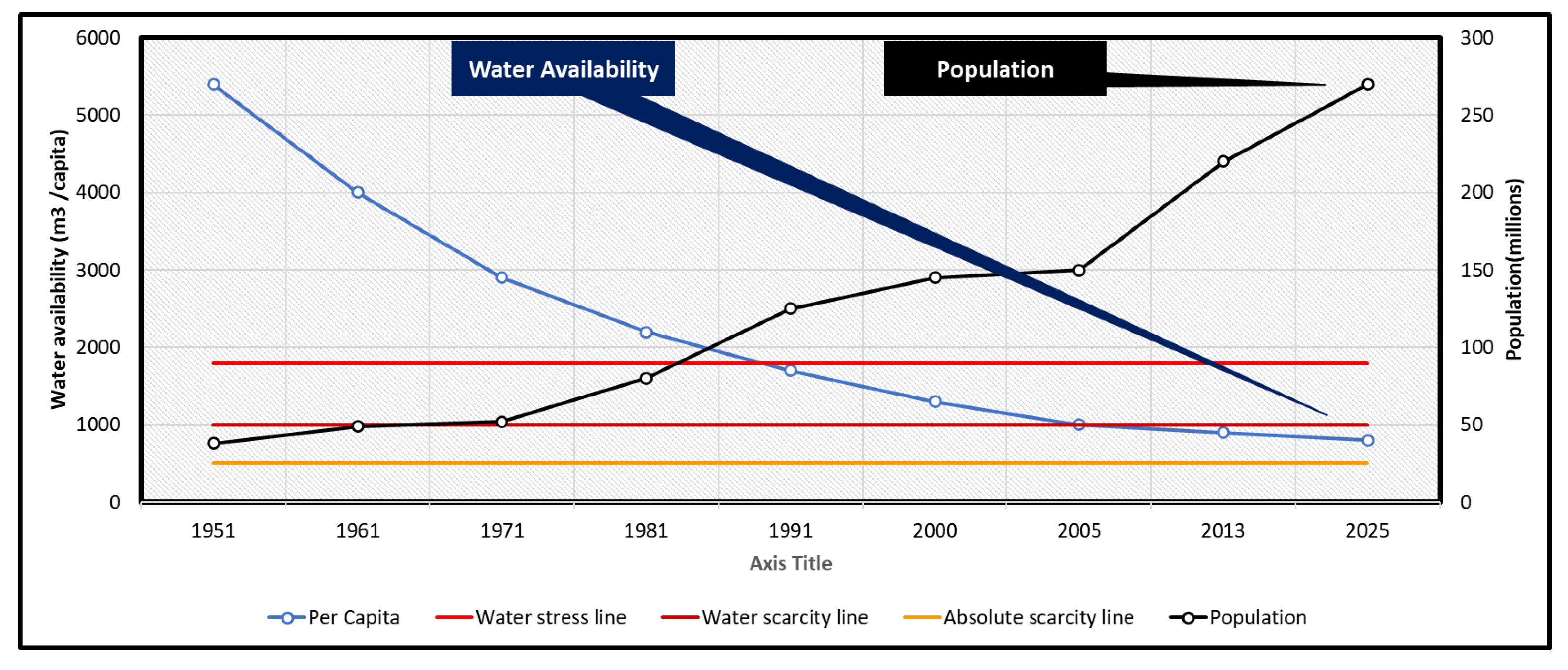

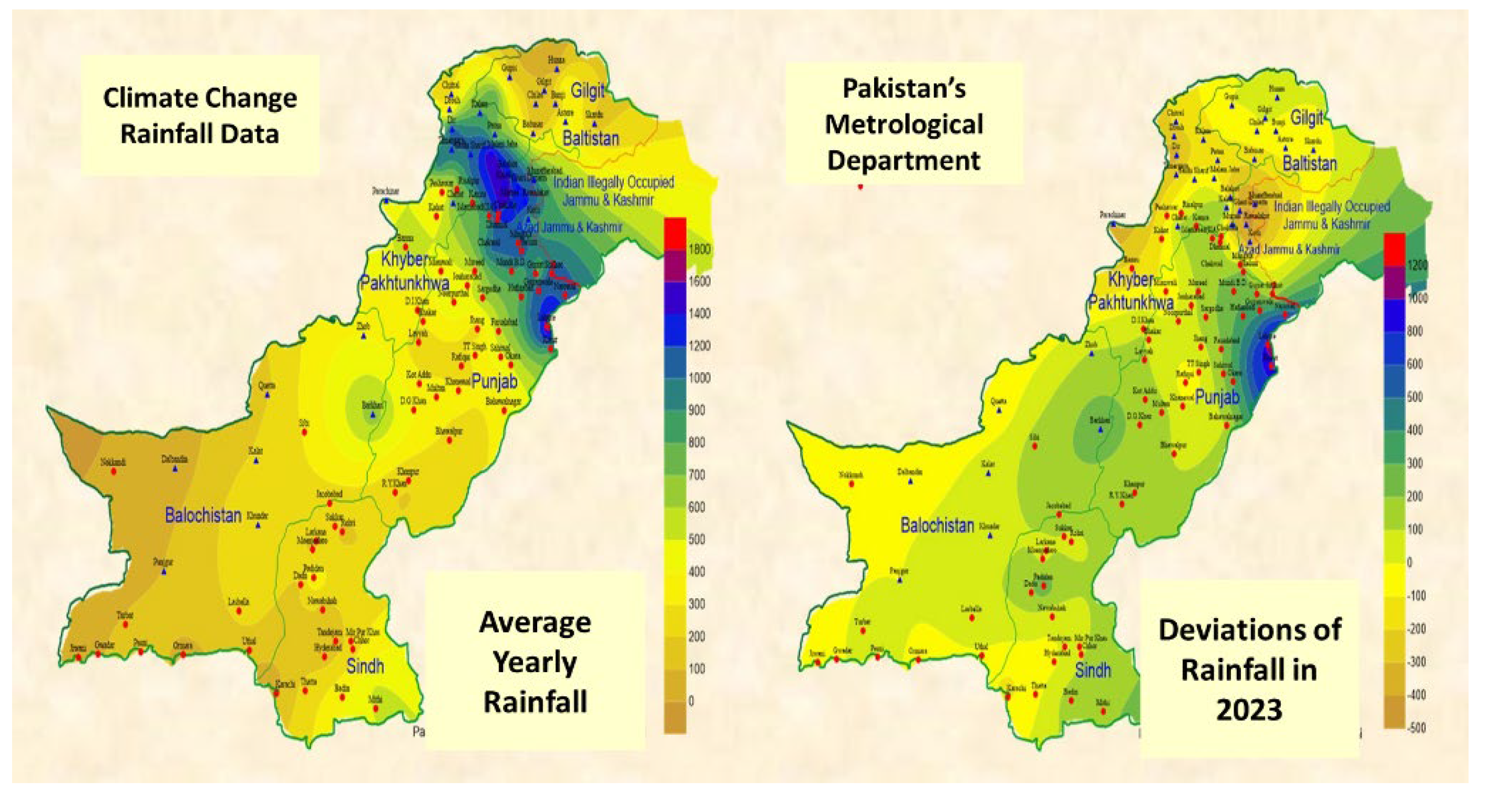

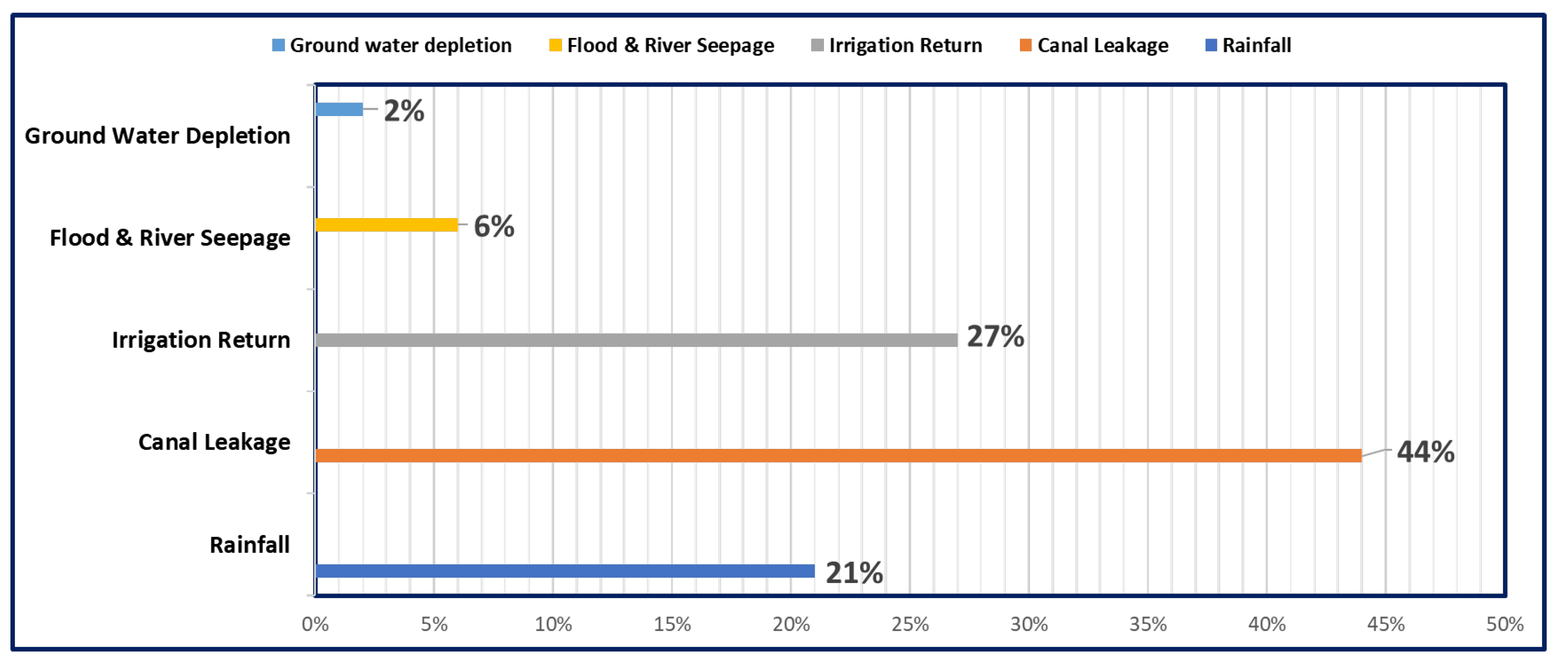

4.7. Water Scarcity in Baluchistan

Recommendations for Ensuring Water Security in Baluchistan

5.1. Water Management, Conservation and Distribution

5.2. Water Quality Monitoring Mechanism

5.3. Recycling of Wastewater

Conclusion

Funding

Ethics committee approval

Data Availability

Conflict of Interest

References

- World Bank World Bank, “World Bank Pakistani Population,” World Bank Open Data, December 19, 2024, https://data.worldbank.org.

- UN Habitat, “Pakistan Country Report 2023” (UN-Habitat, December 31, 2023), https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/06/4._pakistan_country_report_2023_b5_final_compressed.pdf.

- .

- M. K. Daud et al., “Drinking Water Quality Status and Contamination in Pakistan,” BioMed Research International 2017, no. 1 (2017): 7908183, . [CrossRef]

- Azizullah Azizullah et al., “Water Pollution in Pakistan and Its Impact on Public Health — A Review,” Environment International 37, no. 2 (February 1, 2011): 479–97, . [CrossRef]

- Maimoona Raza et al., “Groundwater Status in Pakistan: A Review of Contamination, Health Risks, and Potential Needs,” Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 47, no. 18 (September 17, 2017): 1713–62, . [CrossRef]

- Waseem Ishaque, Rida Tanvir, and Mudassir Mukhtar, “Climate Change and Water Crises in Pakistan: Implications on Water Quality and Health Risks,” Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2022, no. 1 (2022): 5484561, . [CrossRef]

- Waseem Ishaque, Mudassir Mukhtar, and Rida Tanvir, “Pakistan’s Water Resource Management: Ensuring Water Security for Sustainable Development,” Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (January 20, 2023), . [CrossRef]

- Waseem Ishaque, Khalid Sultan, and Zia ur Rehman, “Water Management and Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Environmental and Health Impacts of Water Quality on Achieving the UNSDGs by 2030,” Frontiers in Water 6 (February 8, 2024), . [CrossRef]

- Safdar Bashir et al., “Impacts of Water Quality on Human Health in Pakistan,” in Water Resources of Pakistan: Issues and Impacts, ed. Muhammad Arif Watto, Michael Mitchell, and Safdar Bashir (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021), 225–47, . [CrossRef]

- Misbah Fida et al., “Water Contamination and Human Health Risks in Pakistan: A Review,” Exposure and Health 15, no. 3 (September 1, 2023): 619–39, . [CrossRef]

- Waseem Ishaque, Shuja Mahesar Ahmed, and Imdad Sahito Hussain, “Influence of Climate Change on Pakistan’s National Security,” Grassroots 49, no. 2 (December 31, 2015): 65.

- Mudassar Hussain et al., “A Comprehensive Review of Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Mitigation on Environmental and Natural Calamities in Pakistan,” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 192, no. 1 (December 16, 2019): 48, . [CrossRef]

- Shah Fahad and Jianling Wang, “Climate Change, Vulnerability, and Its Impacts in Rural Pakistan: A Review,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27, no. 2 (January 1, 2020): 1334–38, . [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Aslam Khan et al., “The Challenge of Climate Change and Policy Response in Pakistan,” Environmental Earth Sciences 75, no. 5 (February 24, 2016): 412, . [CrossRef]

- Sajjad Ali et al., “Climate Change and Its Impact on the Yield of Major Food Crops: Evidence from Pakistan,” Foods 6, no. 6 (June 2017): 39, . [CrossRef]

- Sadia Mariam Malik, Haroon Awan, and Niazullah Khan, “Mapping Vulnerability to Climate Change and Its Repercussions on Human Health in Pakistan,” Globalization and Health 8, no. 1 (September 3, 2012): 31, . [CrossRef]

- Toqeer Ahmed et al., “Water-Related Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture and Subsequently on Public Health: A Review for Generalists with Particular Reference to Pakistan,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13, no. 11 (November 2016): 1051, . [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Aamir Khan et al., “Economic Effects of Climate Change-Induced Loss of Agricultural Production by 2050: A Case Study of Pakistan,” Sustainability 12, no. 3 (January 2020): 1216, . [CrossRef]

- Alia Saeed et al., “Modelling the Impact of Climate Change on Dengue Outbreaks and Future Spatiotemporal Shift in Pakistan,” Environmental Geochemistry and Health 45, no. 6 (June 1, 2023): 3489–3505, . [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Nabeel Aslam et al., “Climate Change Impact on Water Scarcity in the Hub River Basin, Pakistan,” Groundwater for Sustainable Development 27, no. 1 (November 1, 2024): 101339, . [CrossRef]

- He Baocheng et al., “Impact of Climate Change on Water Scarcity in Pakistan. Implications for Water Management and Policy,” Journal of Water and Climate Change 15, no. 8 (July 2, 2024): 3602–23, . [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Nabeel Aslam et al., “Climate Change Impact on Water Scarcity in the Hub River Basin, Pakistan,” Groundwater for Sustainable Development 27 (November 1, 2024): 101339, . [CrossRef]

- Khurram Aslam Khan, “Water Scarcity and Its Impact on the Agricultural Sector of Balochistan,” Journal of Public Policy Practitioners 1, no. 1 (June 30, 2022): 01–66, . [CrossRef]

- Khan.

- Shamsul Islam, “Water Availability Has Dropped 500% since 1947,” The Express Tribune, June 20, 2011, sec. News, http://tribune.com.pk/story/193120/water-availability-has-dropped-500-since-194.

- M. K. Daud et al., “Drinking Water Quality Status and Contamination in Pakistan,” BioMed Research International 2017 (August 14, 2017): e7908183, . [CrossRef]

| Types of samples | Sample sites | Container types | Objectives | Preservatives details |

| Type 1 | All | Bottles over 150 ml sterilized | Testing of microbiological contents | Pre-sterilized |

| Type 2 | “ | Polystyrene bottle of 0.5 Liter | Establishing trace elements | Nitric Acid 1.5 to 2 ml in a Liter of sample (HNO 3) |

| Type 3 | “ | Polystyrene bottle of 0.5 Liter | Discovering nitrate presence | Boric Acid 1 ml in a sample of 100 ml |

| Type 4 | “ | Polystyrene bottle of 1 Liter | Presence of other chemicals | Without any preservatives |

| Serial | Place | Code | Grid size km2 | Points for sampling | Remarks |

| Zone 1 (Loralai) | |||||

| 1 | Zhob | ZHB | 4 | 24 | |

| 2 | Loralai | LLI | 4 | 24 | |

| 3 | Barkhan | BKN | 2 | 16 | |

| 4 | Kohlu | KHL | 3 | 20 | |

| Zone 2 (Sibi) | |||||

| 5 | Sibi | SBI | 4 | 24 | |

| 6 | Nushki | NKI | 3 | 20 | |

| 7 | Kalat | KLT | 3 | 20 | |

| 8 | Kharan | KHN | 3 | 20 | |

| 9 | Khuzdar | KZR | 4 | 24 | |

| Zone 3 (Turbat) | |||||

| 10 | Dalbandin | DBN | 3 | 20 | |

| 11 | Nokkundi | NKD | 3 | 20 | |

| 12 | Panjgur | PJR | 3 | 20 | |

| 13 | Turbat | TRT | 3 | 20 | |

| Zone 4 (Coastal) | |||||

| 14 | Jiwani | JWN | 3 | 20 | |

| 15 | Gwadar | GDR | 3 | 20 | |

| 16 | Pasni | PNI | 3 | 20 | |

| 17 | Ormara | OMR | 3 | 20 | |

| Zone 5 (Quetta) | |||||

| 18 | Quetta | QTA | 6 | 34 | |

| Serial | Places | Monitored sources | Number of sample sites |

| 1 | Zone 1 | Filtration Plants (10), Tube wells (21), Tabs (27), Hand Pumps (35), Water Supply (10), Streams (18) | 121 |

| 2 | Zone 2 | Filtration Plants (8), Tube wells (27), Tabs (8), Hand Pumps (30), Streams (13) | 86 |

| 3 | Zone 3 | Filtration Plants (5), Tube wells (30), Tabs (8), Hand Pumps (27), Water Supply (13) | 83 |

| 4 | Zone 4 | Filtration Plants (10), Tube wells (35), Tabs (10), Hand Pumps (33), Water Supply (15) | 103 |

| 5 | Zone 5 | Filtration Plants (47), Tube wells (23), Tabs (59), Hand Pumps (29), Water Supply (33), Streams (15) | 206 |

| Serial | Standard Parameters | Method of analysis |

| 1 | Phosphate (mg/l) | 8190 and 8048 Colorimeters (HACH) |

| 2 | Alkalinity (mg/l as CaCO3) | 2320, Standard method 2017 |

| 3 | Fluoride (mg/l) | 4500-FC.ion-Selective Electrode Method Standard 2017 |

| 4 | Chloride (mg/l) | Titration (Silver Nitrate), Standard Method 2017 |

| 5 | Nitrate as Nitrogen (mg/l) | Cd. Reduction (Hach-8171) by Spectrophotometer |

| 6 | Potassium (mg/l) | Flame photometer PFP7, UK |

| 7 | Total Coliforms | 9221-B,C&D, Standard Methods 2017 APHA |

| 8 | Turbidity (NTU) | Turbidity Meter, Lamotte, Model 2008, USA |

| 9 | Calcium (mg/l) | 3500-Ca-D, Standard Method 2017 |

| 10 | TDS (mg/l) | 2540C, Standard method 2017 |

| 11 | E-coli | 9221-B,C&D, Standard Methods 2017 APHA |

| 12 | Hardness (mg/l) | EDTA Titration, Standard Method 2017 |

| 13 | Magnesium (mg/l) | 2340-C, Standard Method 2017 |

| 14 | pH | pH Meter, Hanna Instrument, Model 8519, Italy |

| 15 | Bicarbonate (mg/l) | 2320, Standard method 2017 |

| 16 | Carbonate (mg/l) | 2320, Standard method 2017 |

| 17 | Sodium (mg/l) | Flame photometer PFP7, UK |

| 18 | Arsenic (ppb) | AAS Vario 6, Analytik Jena AG (3111B APHA) 2017 |

| 19 | Conductivity (μS/cm) | E.C meter, Hach-44600-00, USA |

| 20 | Sulphate (mg/l) | SulfaVer4 (Hach-8051) by Spectrophotometer |

| Serial | Parameters | Units | Limits |

| 1 | Sodium | mg/l | NGVS |

| 2 | TDS | mg/l | 1000 |

| 3 | Calcium | mg/l | NGVS |

| 4 | E-coli | CFU/100ml | 0 |

| 5 | Magnesium | mg/l | NGVS |

| 6 | Sulphate | mg/l | NGVS |

| 7 | Potassium | mg/l | NGVS |

| 8 | Bicarbonate | mg/l | NGVS |

| 9 | Chloride | mg/l | 250 |

| 10 | pH | - | 6.51-8.51 |

| 11 | Arsenic | µg/l | 51 |

| 12 | Nitrate-N | mg/l | 10.05 |

| 13 | Fluoride | mg/l | 1.53 |

| 14 | Alkalinity | mg/l | NGVS |

| 15 | Hardness | mg/l | 500 |

| 16 | Carbonate | mg/l | NGVS |

| 17 | Turbidity | NTU | <5 |

| 18 | Conductivity | µS/cm | NGVS |

| 19 | Total Coliforms | CFU/100ml | 0 |

| 20 | Colour | TCU | Colourless |

| 21 | Iron | mg/l | 0.31 |

| Serial | Score | Risk Assessment | Type of Contamination |

| 1 | 0 | Marginally Safe | Level of dissolved Solids, Coliforms, Fluoride, and Nitrate within limits |

| 2 | 1 | Low | Bacterial contamination only (Total Coliforms & Faecal Coliforms) |

| 3 | 2 | Low | Dissolved solids only |

| 4 | 4 | Medium | Single microbial & chemical contamination |

| 5 | 3 | Medium | Single chemical contamination |

| 6 | 5 | High | Double chemical contamination |

| 7 | 6 | High | Numerous chemicals & microbial contamination |

| Ser | Risk Type | Range |

| 1 | Low | 1-2 |

| 2 | Medium | 3-4 |

| 3 | High | 5-6 |

| Serial | Water Quality Parameter (WQP) | Unit of measurement | Samples tested | Contaminated Samples | Contamination percentage |

| 1 | Arsenic (As) | µg/l | 121 | 46 | 38% |

| 2 | Coliform | MPN/100 ml | 121 | 49 | 40% |

| 3 | TDS | mg/l | 121 | 48 | 39% |

| 4 | E. coli | MPN/100 ml | 121 | 52 | 42% |

| 5 | Iron (Fe) | mg/l | 121 | 49 | 40% |

| 6 | Overall contamination percentage | 40% | |||

| Serial | Water Quality Parameter (WQP) | Unit of measurement | Samples tested | Contaminated Samples | Contamination percentage |

| 1 | Arsenic (As) | µg/l | 86 | 48 | 55% |

| 2 | Coliform | MPN/100 ml | 86 | 51 | 59% |

| 3 | TDS | mg/l | 86 | 46 | 53% |

| 4 | E. coli | MPN/100 ml | 86 | 52 | 60% |

| 5 | Iron (Fe) | mg/l | 86 | 54 | 62% |

| 6 | Overall contamination percentage | 58% | |||

| Serial | Water Quality Parameter (WQP) | Unit of measurement | Samples tested | Contaminated Samples | Contamination percentage |

| 1 | Arsenic (As) | µg/l | 83 | 51 | 61% |

| 2 | Coliform | MPN/100 ml | 83 | 49 | 59% |

| 3 | TDS | mg/l | 83 | 55 | 66% |

| 4 | E. coli | MPN/100 ml | 83 | 48 | 57% |

| 5 | Iron (Fe) | mg/l | 83 | 51 | 61% |

| 6 | Overall contamination percentage | 61% | |||

| Serial | Water Quality Parameter (WQP) | Unit of measurement | Samples tested | Contaminated Samples | Contamination percentage |

| 1 | Arsenic (As) | µg/l | 103 | 52 | 50% |

| 2 | Coliform | MPN/100 ml | 103 | 54 | 52% |

| 3 | TDS | mg/l | 103 | 45 | 43% |

| 4 | E. coli | MPN/100 ml | 103 | 53 | 51% |

| 5 | Iron (Fe) | mg/l | 103 | 55 | 53% |

| 6 | Turbidity | NTU | 103 | 49 | 48% |

| 6 | Overall contamination percentage | 50% | |||

| Serial | Water Quality Parameter (WQP) | Unit of measurement | Samples tested | Contaminated Samples | Contamination percentage |

| 1 | Arsenic (As) | µg/l | 206 | 81 | 39% |

| 2 | Coliform | MPN/100 ml | 206 | 87 | 42% |

| 3 | TDS | mg/l | 206 | 93 | 45% |

| 4 | E. coli | MPN/100 ml | 206 | 91 | 44% |

| 5 | Iron (Fe) | mg/l | 206 | 93 | 45% |

| 6 | Hardness | mg/l | 206 | 23 | 13% |

| 7 | Fluoride (F) | mg/l | 206 | 88 | 42% |

| 8 | Overall contamination percentage | 43% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).