Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Animals and animal welfare

- Control Group: Received phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) intraperitoneally (i.p.) three times per week for 6 weeks.

- GV1001 Group: Received GV1001 (2 mg/kg) i.p. three times per week for 6 weeks. This dosage has been demonstrated to be effective for its anti-inflammatory effect without causing toxicity [14].

- Cisplatin + PBS Group: Received cisplatin (2.5 mg/kg) i.p. twice per week for 6 weeks, along with PBS i.p. injections three times per week for 6 weeks.

- Cisplatin + GV1001 Group: Received cisplatin (2.5 mg/kg) i.p. twice per week for 6 weeks, in combination with GV1001 (2 mg/kg) i.p. three times per week for 6 weeks.

2.3. Sample and tissue collections

2.4. Histological analysis

2.5. Histological and Immunofluorescence (IF) Analysis

2.6. Apoptosis assessment

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

2.8. Western blotting

2.9. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

2.10. ATP detection assay

2.11. Labelling GV1001 with Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)

2.12. Cardiolipin binding assay

2.13. Subcellular fractionation

2.14. Statistical analyses

3. Results

3.1. GV1001 notably ameliorated cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity

3.2. GV1001 inhibited the expression of genes associated with the cisplatin-induced kidney injury

3.3. GV1001 suppressed the cisplatin-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of kidney epithelium of mice

3.4. GV1001 inhibited the cisplatin-induced systemic and renal inflammation in mice

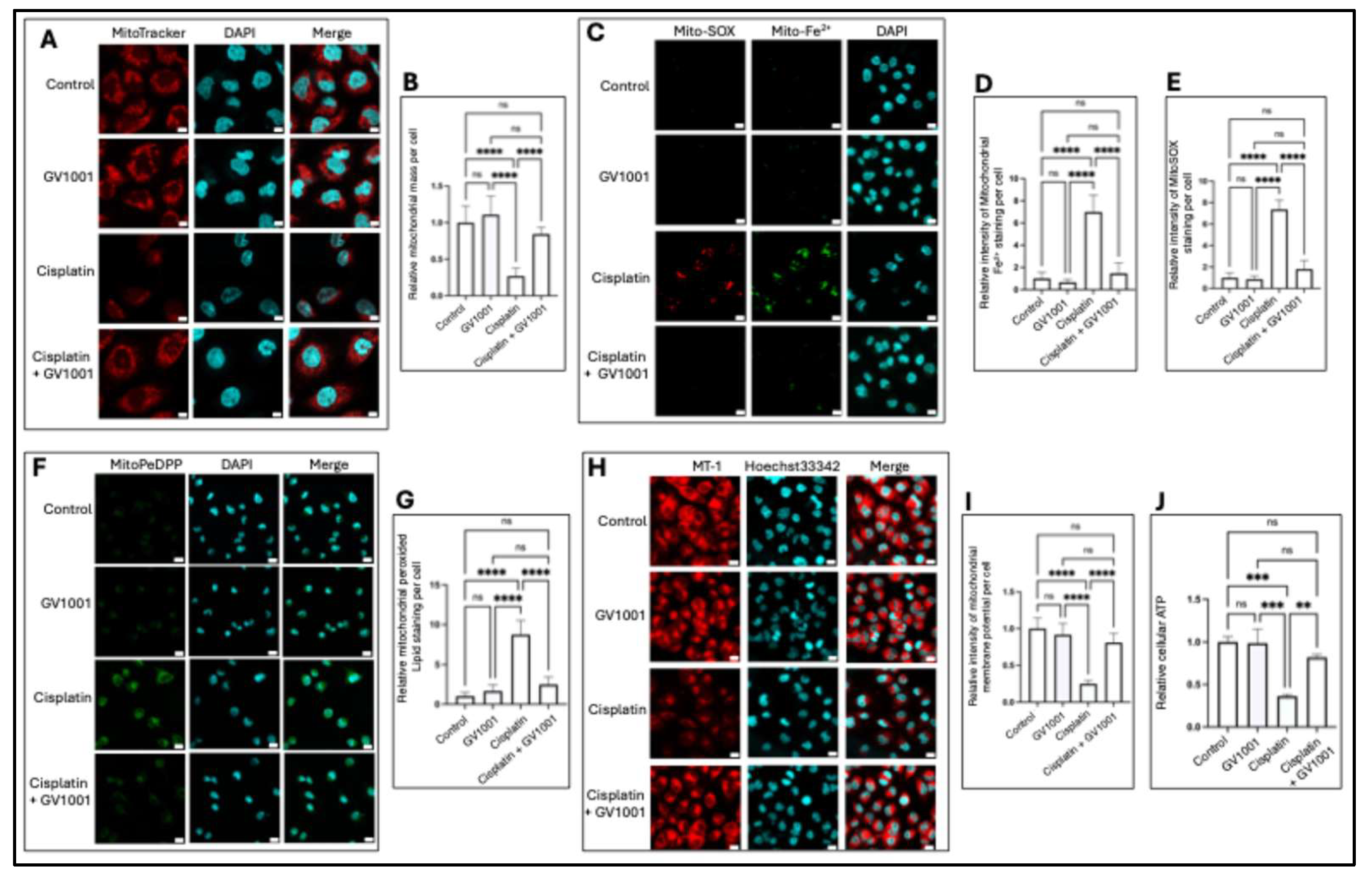

3.5. Cisplatin altered mitochondrial mass and function, while GV1001 reversed such structural and functional changes

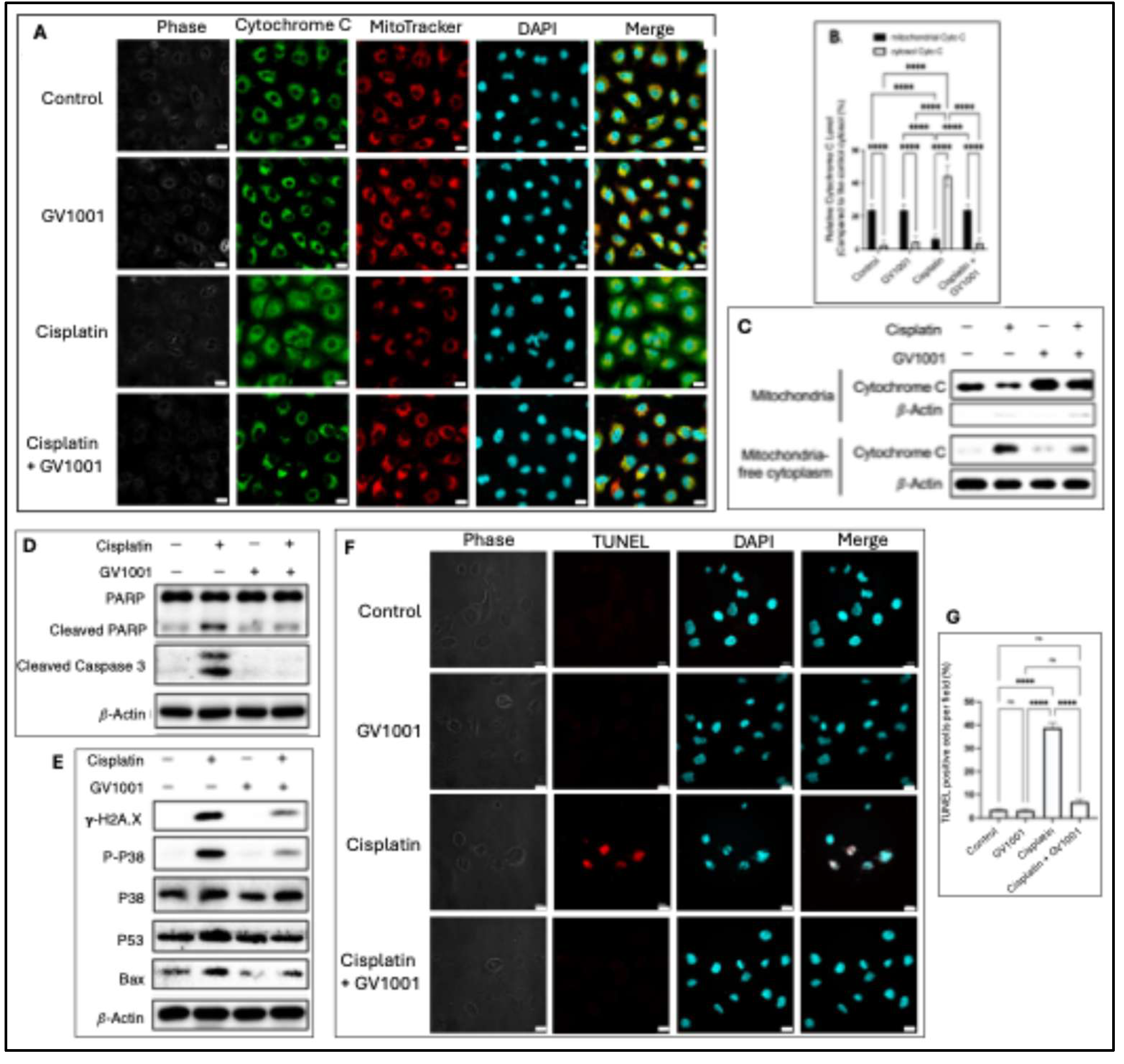

3.6. GV1001 alleviated cisplatin-caused apoptosis in HK-2 cells.

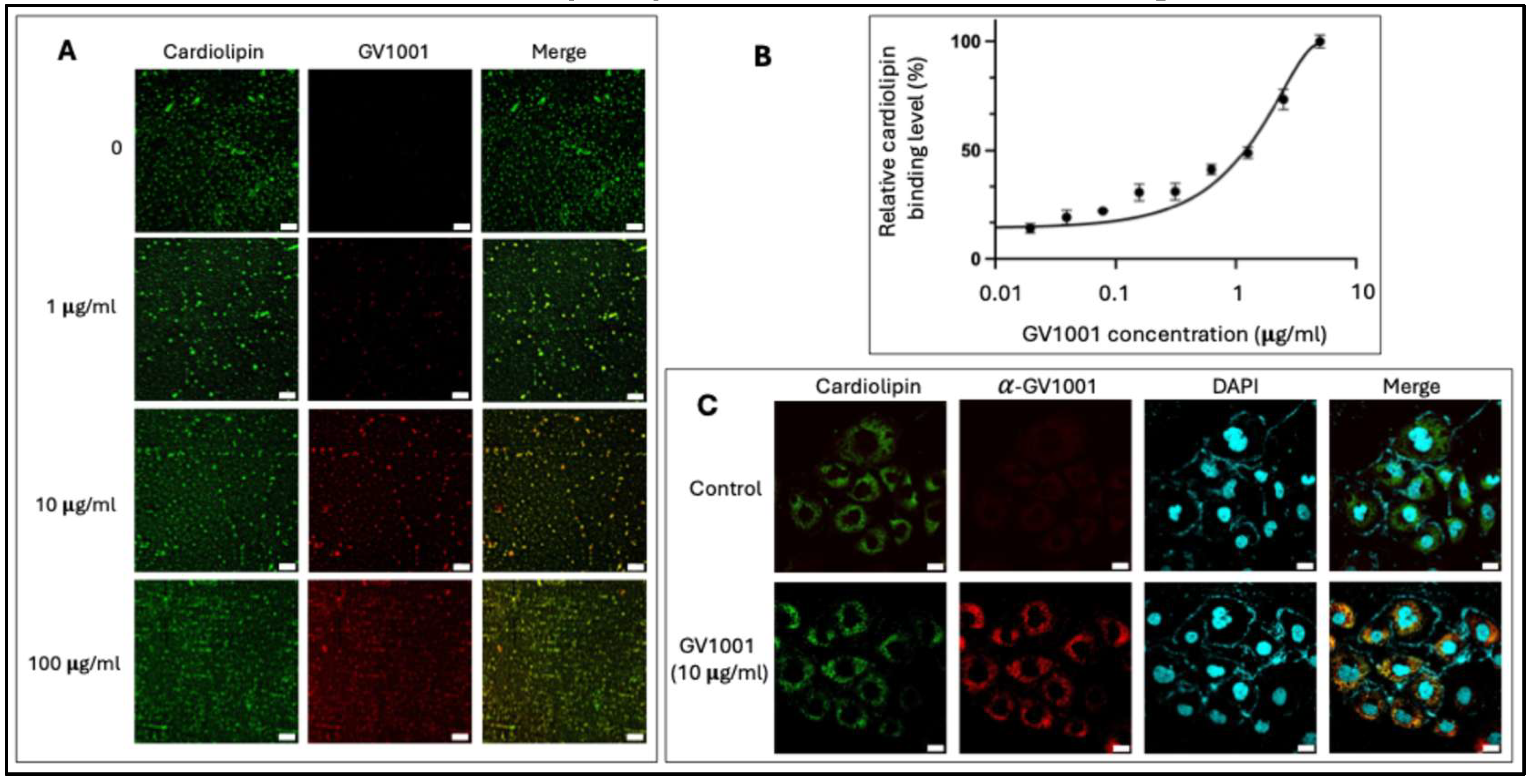

3.7. GV1001 bound to mitochondrial cardiolipin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 740, 364-378. [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, M.; Jadidi, Y.; Moayedi, K.; Farrokhi, V.; Afrisham, R. Ameliorative impacts of polymeric and metallic nanoparticles on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: a 2011-2022 review. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 504.

- Qi, L.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F. Advances in Toxicological Research of the Anticancer Drug Cisplatin. Chem Res Toxicol 2019, 32, 1469-1486. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.P.; Tadagavadi, R.K.; Ramesh, G.; Reeves, W.B. Mechanisms of Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel) 2010, 2, 2490-2518.

- Yao, X.; Panichpisal, K.; Kurtzman, N.; Nugent, K. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: a review. Am J Med Sci 2007, 334, 115-124.

- Sikking, C.; Niggebrugge-Mentink, K.L.; van der Sman, A.S.E.; Smit, R.H.P.; Bouman-Wammes, E.W.; Beex-Oosterhuis, M.M.; van Kesteren, C. Hydration Methods for Cisplatin Containing Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2024, 29, e173-e186. [CrossRef]

- Kleih, M.; Bopple, K.; Dong, M.; Gaissler, A.; Heine, S.; Olayioye, M.A.; Aulitzky, W.E.; Essmann, F. Direct impact of cisplatin on mitochondria induces ROS production that dictates cell fate of ovarian cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 851.

- Bhargava, P.; Schnellmann, R.G. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017, 13, 629-646. [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 909-950. [CrossRef]

- Zorova, L.D.; Popkov, V.A.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Babenko, V.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Balakireva, A.V.; Juhaszova, M.; et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential. Anal Biochem 2018, 552, 50-59.

- Kim, S.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.K.; Ryu, H.; Choi, D.R.; Hwang, I.G.; Song, H.; Kwon, J.H.; et al. A phase II study of chemotherapy in combination with telomerase peptide vaccine (GV1001) as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Cancer 2022, 13, 1363-1369. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, S.; Shon, W.J.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.H.; Kang, M.K. hTERT peptide fragment GV1001 demonstrates radioprotective and antifibrotic effects through suppression of TGF-beta signaling. Int J Mol Med 2018, 41, 3211-3220.

- Park, H.H.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.W.; Choi, N.Y.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Koh, S.H. Novel vaccine peptide GV1001 effectively blocks beta-amyloid toxicity by mimicking the extra-telomeric functions of human telomerase reverse transcriptase. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 1255-1274.

- Chen, W.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, A.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, C.; Ton-That, H.; Kim, R.; Kim, S.; Park, N.H. hTERT Peptide Fragment GV1001 Prevents the Development of Porphyromonas gingivalis-Induced Periodontal Disease and Systemic Disorders in ApoE-Deficient Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6126. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Beheshtian, C.; Kim, N.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, R.H.; Kim, S.; Park, N.H. GV1001, hTERT Peptide Fragment, Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Endothelial Cells and Atherosclerosis in Mice. Cells 2025, 14, 98.

- Choi, I.A.; Choi, J.Y.; Jung, S.; Basri, F.; Park, S.; Lee, E.Y. GV1001 immunotherapy ameliorates joint inflammation in a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis by modifying collagen-specific T-cell responses and downregulating antigen-presenting cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2017, 46, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tian, Y.; Sun, F.; Lei, G.; Cheng, J.; Tian, C.; Yu, H.; Deng, Z.; Lu, S.; Wang, L.; et al. A Recombinant Oncolytic Influenza Virus Carrying GV1001 Triggers an Antitumor Immune Response. Hum Gene Ther 2024, 35, 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Momeni, M.; Lee, A.; Treanor, A.; Kim, S.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.H. GV1001 Inhibits the Severity of the Ligature-Induced Periodontitis and the Vascular Lipid Deposition Associated with the Periodontitis in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12566. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.H.; Yu, H.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Choi, N.Y.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Yoon, M.Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Koh, S.H. Neural stem cells injured by oxidative stress can be rejuvenated by GV1001, a novel peptide, through scavenging free radicals and enhancing survival signals. Neurotoxicology 2016, 55, 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Kim, J.; Sim, J.; Kim, S.G.; Kook, Y.H.; Park, C.G.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, B.J. A telomerase-derived peptide regulates reactive oxygen species and hepatitis C virus RNA replication in HCV-infected cells via heat shock protein 90. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 471, 156-162.

- Ma, N.; Wei, Z.; Hu, J.; Gu, W.; Ci, X. Farrerol Ameliorated Cisplatin-Induced Chronic Kidney Disease Through Mitophagy Induction via Nrf2/PINK1 Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 768700. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.K.; Conway, E.M.; Harris, R.C. Survivin mediates renal proximal tubule recovery from AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 24, 2023-2033.

- Jang, S.K.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Hong, J.; Park, K.S.; Park, I.C.; Jin, H.O. Inhibition of VDAC1 oligomerization blocks cysteine deprivation-induced ferroptosis via mitochondrial ROS suppression. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 811. [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, T.; Ikeda, M.; Ide, T.; Deguchi, H.; Ikeda, S.; Okabe, K.; Ishikita, A.; Matsushima, S.; Koumura, T.; Yamada, K.I.; et al. Mitochondria-dependent ferroptosis plays a pivotal role in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e132747.

- Bharat, V.; Durairaj, A.S.; Vanhauwaert, R.; Li, L.; Muir, C.M.; Chandra, S.; Kwak, C.S.; Le Guen, Y.; Nandakishore, P.; Hsieh, C.H.; et al. A mitochondrial inside-out iron-calcium signal reveals drug targets for Parkinson's disease. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 113544. [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.S.; Lee, S.H.; Fouladian, Z.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, T.; Kang, M.K.; Lusis, A.J.; Bostrom, K.I.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.H. Rosuvastatin Prevents the Exacerbation of Atherosclerosis in Ligature-Induced Periodontal Disease Mouse Model. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 6383. [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.S.; Kim, S.Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.H. Hyperlipidemia is necessary for the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis by severe periodontitis in mice. Mol Med Rep 2022, 26, 273.

- Lin, H.Y.; Liang, C.J.; Yang, M.Y.; Chen, P.L.; Wang, T.M.; Chen, Y.H.; Shih, Y.H.; Liu, W.; Chiu, C.C.; Chiang, C.K.; et al. Critical roles of tubular mitochondrial ATP synthase dysfunction in maleic acid-induced acute kidney injury. Apoptosis 2024, 29, 620-634. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Preiss, N.K.; Valenteros, K.B.; Kamal, Y.; Usherwood, Y.K.; Frost, H.R.; Usherwood, E.J. Zbtb20 Restrains CD8 T Cell Immunometabolism and Restricts Memory Differentiation and Antitumor Immunity. J Immunol 2020, 205, 2649-2666. [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R.; Malicka, J.; Huang, J.; Gryczynski, Z.; Gryczynski, I. Ultrabright fluorescein-labeled antibodies near silver metallic surfaces. Biopolymers 2004, 74, 467-475.

- Hwang, K.Y.; Choi, Y.B. Modulation of Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling by Human Herpesvirus 8 Interferon Regulatory Factor 1. J Virol 2016, 90, 506-520.

- McSweeney, K.R.; Gadanec, L.K.; Qaradakhi, T.; Ali, B.A.; Zulli, A.; Apostolopoulos, V. Mechanisms of Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: Pathological Mechanisms, Pharmacological Interventions, and Genetic Mitigations. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1572. [CrossRef]

- Ozkok, A.; Edelstein, C.L. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 967826.

- Roncal, C.A.; Mu, W.; Croker, B.; Reungjui, S.; Ouyang, X.; Tabah-Fisch, I.; Johnson, R.J.; Ejaz, A.A. Effect of elevated serum uric acid on cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007, 292, F116-122. [CrossRef]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Radu, S.; Costea, C.F.; Ciocoiu, M.; Carauleanu, A.; Lacatusu, C.M.; Maranduca, M.A.; Floria, M.; Rezus, C. The Predictive Role of the Biomarker Kidney Molecule-1 (KIM-1) in Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 5238.

- Chen, S.; Xue, K.; Zhao, R.; Chai, J.; Zhu, X.; Kong, X.; Ding, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, W. Insufficient S-sulfhydration of cAMP-response element binding protein 1 participates in hyperhomocysteinemia or cisplatin induced kidney fibrosis via promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Free Radic Biol Med 2025, 237, 312-325. [CrossRef]

- Mihai, S.; Codrici, E.; Popescu, I.D.; Enciu, A.M.; Albulescu, L.; Necula, L.G.; Mambet, C.; Anton, G.; Tanase, C. Inflammation-Related Mechanisms in Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction, Progression, and Outcome. J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 2180373.

- Verissimo, T.; de Seigneux, S. New evidence of the impact of mitochondria on kidney health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2024, 20, 81-82.

- Wang, Y.; Cai, J.; Tang, C.; Dong, Z. Mitophagy in Acute Kidney Injury and Kidney Repair. Cells 2020, 9, 338.

- Pham, L.; Arroum, T.; Wan, J.; Pavelich, L.; Bell, J.; Morse, P.T.; Lee, I.; Grossman, L.I.; Sanderson, T.H.; Malek, M.H.; et al. Regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation through tight control of cytochrome c oxidase in health and disease - Implications for ischemia/reperfusion injury, inflammatory diseases, diabetes, and cancer. Redox Biol 2024, 78, 103426. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Sun, X.A.; Wang, X.; Yang, N.H.; Xie, H.Y.; Guo, H.J.; Lu, L.; Xie, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; et al. PGAM5 exacerbates acute renal injury by initiating mitochondria-dependent apoptosis by facilitating mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2024, 45, 125-136. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.F.; Hu, Y.C.; Kang, B.H.; Tseng, Y.K.; Wu, P.C.; Liang, C.C.; Hou, Y.Y.; Fu, T.Y.; Liou, H.H.; Hsieh, I.C.; et al. Expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-3 in tumorigenesis and prognosis of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0180620. [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, A.S.; Denisenko, T.V.; Yapryntseva, M.A.; Pivnyuk, A.D.; Prikazchikova, T.A.; Gogvadze, V.G.; Zhivotovsky, B. BNIP3 as a Regulator of Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2020, 85, 1245-1253.

- Tait, S.W.; Green, D.R. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11, 621-632.

- Jiang, Z.; Shen, T.; Huynh, H.; Fang, X.; Han, Z.; Ouyang, K. Cardiolipin Regulates Mitochondrial Ultrastructure and Function in Mammalian Cells. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 1889.

- Tang, C.; Livingston, M.J.; Safirstein, R.; Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: new insights and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Nephrol 2023, 19, 53-72. [CrossRef]

- Strader, M.; Friedman, G.; Benain, X.; Camerlingo, N.; Sultana, S.; Shapira, S.; Aber, N.; Murray, P.T. Early and Sensitive Detection of Cisplatin-Induced Kidney Injury Using Novel Biomarkers. Kidney Int Rep 2025, 10, 1175-1187.

- Virzi, G.M.; Morisi, N.; Oliveira Paulo, C.; Clementi, A.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin: Biological Aspects and Potential Diagnostic Use in Acute Kidney Injury. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 1570.

- Huang, R.; Fu, P.; Ma, L. Kidney fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 129.

- Hadpech, S.; Thongboonkerd, V. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in kidney fibrosis. Genesis 2024, 62, e23529. [CrossRef]

- Elmorsy, E.A.; Saber, S.; Hamad, R.S.; Abdel-Reheim, M.A.; El-Kott, A.F.; AlShehri, M.A.; Morsy, K.; Salama, S.A.; Youssef, M.E. Advances in understanding cisplatin-induced toxicity: Molecular mechanisms and protective strategies. Eur J Pharm Sci 2024, 203, 106939.

- Hirata, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Yamada, Y.; Matsui, R.; Inoue, A.; Ashida, R.; Noguchi, T.; Matsuzawa, A. trans-Fatty acids promote p53-dependent apoptosis triggered by cisplatin-induced DNA interstrand crosslinks via the Nox-RIP1-ASK1-MAPK pathway. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 10350.

- Fuentes, J.M.; Morcillo, P. The Role of Cardiolipin in Mitochondrial Function and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 609.

- Onuigbo, M. Renoprotection and the Bardoxolone Methyl Story - Is This the Right Way Forward? A Novel View of Renoprotection in CKD Trials: A New Classification Scheme for Renoprotective Agents. Nephron Extra 2013, 3, 36-49.

- Louvis, N.; Coulson, J. Renoprotection by Direct Renin Inhibition: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2018, 16, 157-167.

- Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, W.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Gu, S.; Xu, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y. Renoprotection of Microcystin-RR in Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction-Induced Renal Fibrosis: Targeting the PKM2-HIF-1alpha Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 830312.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).