Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Leaf and Fruit Sampling

2.2. RT-PCR Analysis

2.3. Preparation of Blueberry Extracts

2.4. Determination of Total Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, Phenolics, and Antioxidant Capacity

2.5. UHPLC Q-ToF MS Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. BlMaV Detection

3.2. Quantification of Total Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, and Phenolics and Determination of Antioxidatove Capacity

3.3. Identification of Phenolic Compounds

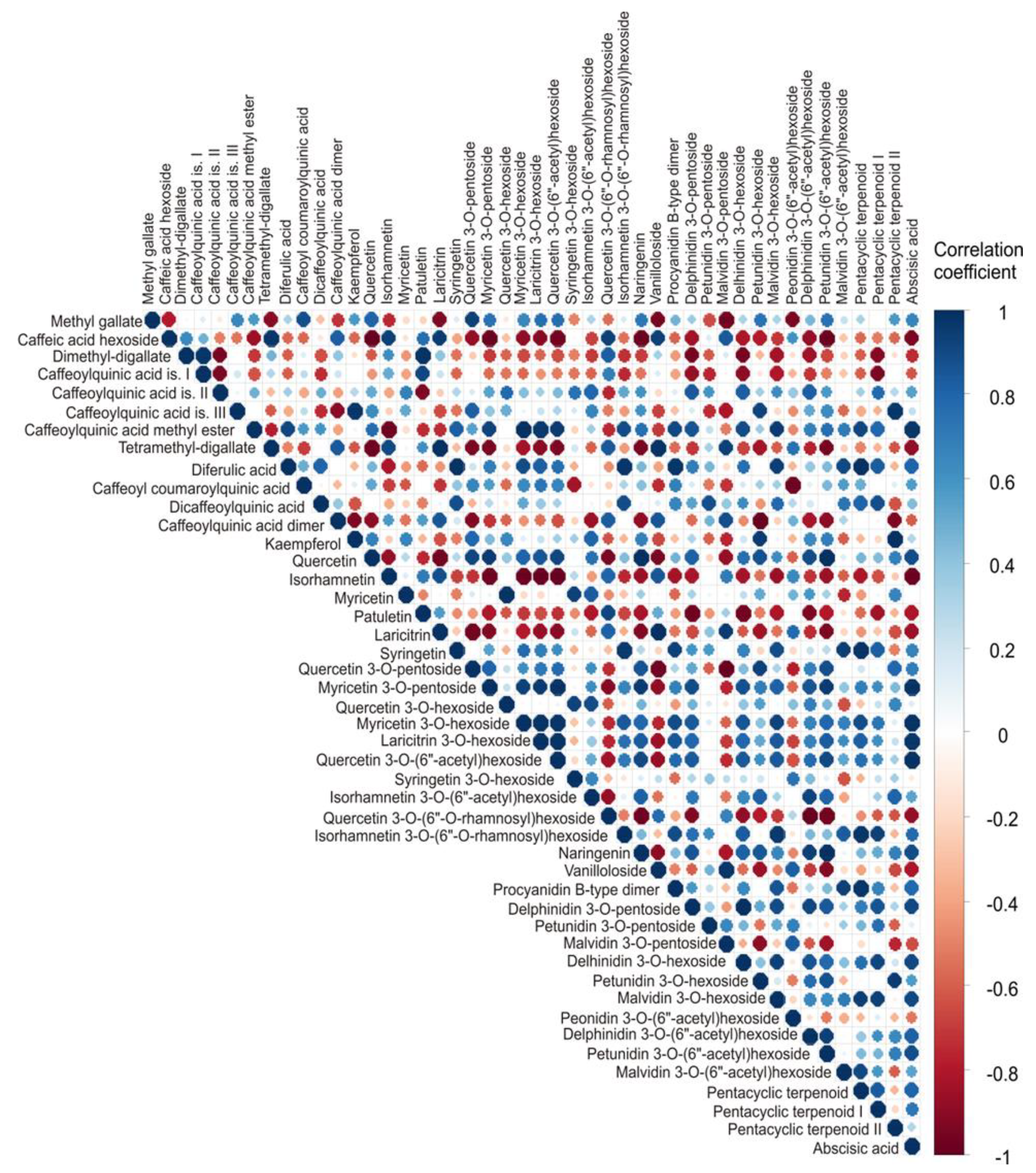

3.4. Color Correlation Analysis

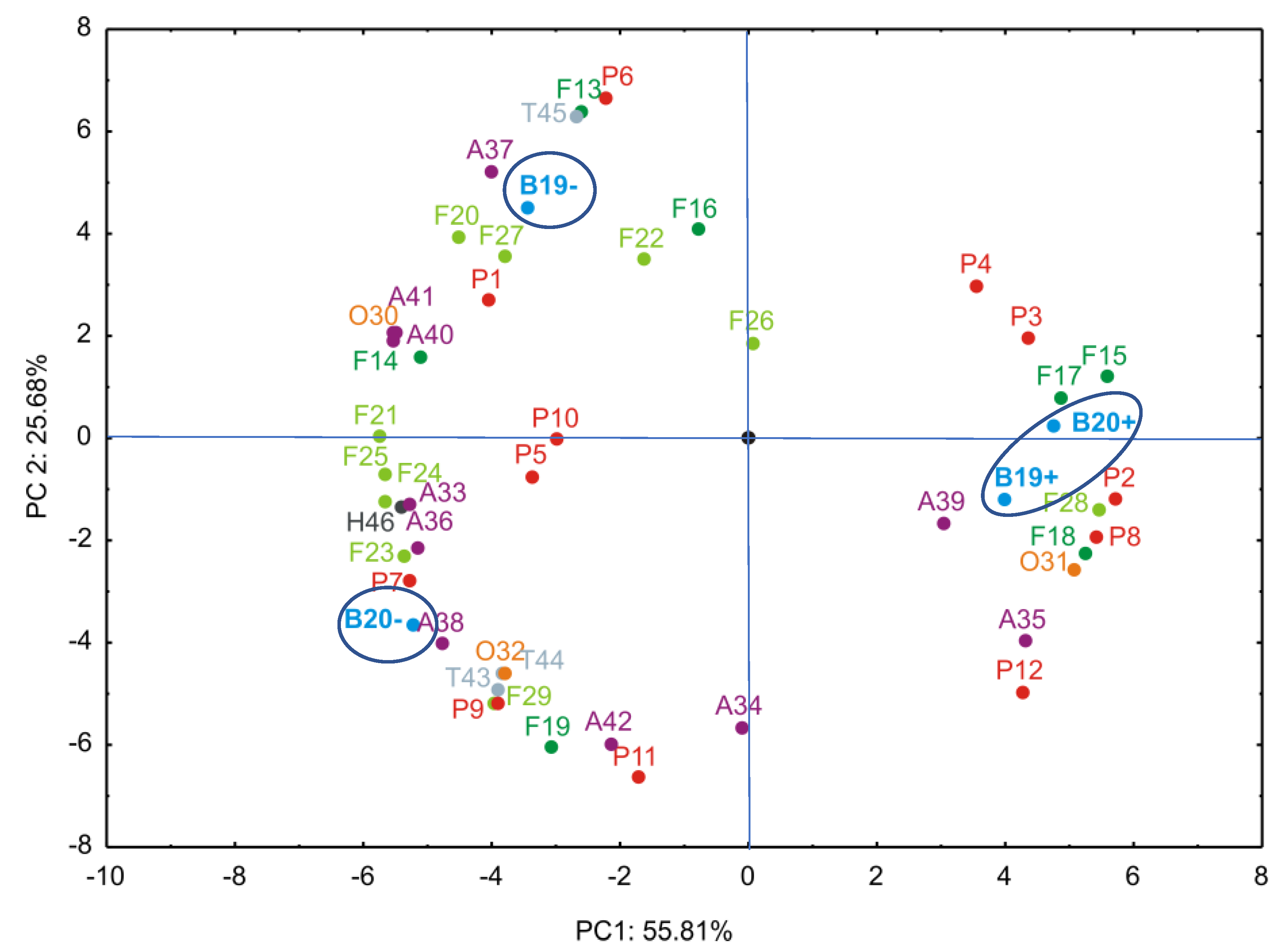

3.5. Principal Component Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BlMaV | Blueberry mosaic associated ophiovirus |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| BSV, BlShV | Blueberry shock virus |

| BLMoV | Blueberry leaf mottle virus |

| BlScV | Blueberry scorch virus |

| BSSV | Blueberry shoestring virus |

| ToRSV | Tomato ringspot virus |

| TRSV | Tobacco ringspot virus |

| PRMV | Peach rosette mosaic virus |

| C3GE | Cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalents |

| CE | Catechin equivalents |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| UHPLC Q-ToF MS | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Ma, L.; Sun, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, M.; Yang, J. Molecular mechanism and health role of functional ingredients in blueberry for chronic disease in human beings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT (2025). Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Leposavić, A.; Jevremović, D. Borovnica - Tehnologije gajenja, zaštite i prerade. Naučno voćarsko društvo Srbije: Čačak, Serbia, 2020.

- Retamales, J.B.; Hancock, J.F. Blueberries, 2nd ed.; Cabi; Glasgow, UK, 2018.

- Saad, N.; Olmstead, J.W.; Jones, J.B.; Varsani, A.; Harmon, P.F. Known and new emerging viruses infecting blueberry. Plants 2021, 10, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekke-Veetil, T.; Ho, T.; Keller, K.E.; Martin, R.R.; Tzanetakis, I.E. A new ophiovirus is associated with blueberry mosaic disease. Virus Res. 2014, 189, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsdell, D.C.; Stretch, A.W. Blueberry mosaic. In Virus Diseases of Small Fruits; Converse, R.H., Ed.; US Government Printing Office, US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, D.C., USA, 1987; Agricultural Handbook (USDA), number 631, pp. 119−120.

- Jevremović, D.; Vasilijević, B.; Leposavić, A.; Katanić, V. (2024) Molecular Characterization of Blueberry Mosaic-Associated Virus in Highbush Blueberries in Serbia. In Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific Conference: Modern Trends in Agricultural Production, Rural Development, Agroeconomy, Cooperatives and Environmental Protection, Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia, 27-28 June 2024, pp. 89−94.

- Jevremović, D.; Paunović, A. S.; Leposavić, A. Influence of blueberry mosaic associated virus on some fruit traits of highbush blueberry ‘Duke’. J. Mt. Agric. Balk. 2020, 23, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Mock, R.; Huang, Q.; Abad, J.; Hartung, J. , Kinard, G. A reliable and inexpensive method of nucleic acid extraction for the PCR-based detection of diverse plant pathogens. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 154, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevremović, D.; Leposavić, A.; Paunović, S. Incidence of viruses in highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) in Serbia. Pestic. Fitomed. 2016, 31, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Cao, G. , Martin, A., Sofic, E., McEwen, J., O’Brien, C., et al. Antioxidant capacity as influenced by total phenolic and anthocyanin content, maturity, and variety of Vaccinium species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. , Li, X.Q., Weber, C., Lee, C.Y., Brown, J., Liu, R.H. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of raspber ries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2926–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J. , Mengcheng, T., Jianming, W. The de termination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L. , Orthofer, R., Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation sub strates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Vrhovsek, U.; Masuero, D.; Palmieri, L.; Mattivi, F. Identification and quantification of flavonol glycosides in cultivated blueberry cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 25, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, P.C.; Liang, Y.C.; Huang, G.J.; Lin, M.K.; Kao, M.C.; Lu, T.L.; Sung, P.J.; Kuo, Y.H. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory terpenoids from the whole plant of Vaccinium emarginatum. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenas, N.; Ruales, J.; Moreno, D.A.; Barrio, D.A.; Stinco, C:M.; Martínez-Cifuentes, G.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; García-Ruiz, A. Characterization of Andean blueberry in bioactive compounds, evaluation of biological properties, and in vitro bioaccessibility. Foods 2020, 9, 1483. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Shen, S.; Schug, K.A. General method for extraction of blueberry anthocyanins and identification using high performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-ion trap-time of flight-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 4728–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Savić, Z.; Brala, A.; Levaj, B.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Biško, A. Evaluation of phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of blueberry cultivars (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) grown in the Northwest Croatia. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 48, 214–221.

- Okan, O.T.; Deniz, I.; Yayli, N.; Şat, I.G.; Öz, M.; Hatipoglu Serdar, G. Antioxidant activity, sugar content and phenolic profiling of blueberries cultivars: A comprehensive comparison. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobo. 2018, 46, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, Y.; Ohara, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Akimoto, M. Total anthocyanin content, total phenolic content, and antioxidant activity of various blueberry cultivars grown in Togane, Chiba Prefecture, Japan. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2021, 67, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, V.; Zhong, B.; Nawaz, M.A.; Barrow, C.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A.R. Screening of phenolic compounds in Australian grown berries by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS and determination of their antioxidant potential. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 26. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Dong, K.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, H. Identification and quantification of anthocyanins of 62 blueberry cultivars via UPLC-MS. Biotechnol. Biotec. Eq. 2022, 36, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, A.R.; Siebeneichler, T.J.; Oliveira Fischer, L.; Holz, Í.R.; Rombaldi, C.V.; Santos Oliveira, B.A.; Oliveira Fischer, D.L.; Silva, C.S.; Helbig, E. Physicochemical characterization, phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of genotypes and commercial cultivars of blueberry fruits. Cienc. Rural 2023, 53, e20220450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araniti, F.; Baron, G.; Ferrario, G.; Pesenti, M.; Vedova, L.D.; Prinsi, B.; Sacchi, G.A.; Aldini, G.; Espen, L. Chemical profiling and antioxidant potential of berries from six blueberry genotypes harvested in the Italian Alps in 2020: A comparative biochemical pilot study. Agronomy 2025, 15, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zang, H.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Xin, X.; Li, Y. A systematic study on composition and antioxidant of 6 varieties of highbush blueberries by 3 soil matrixes in China. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancillotti, C.; Ciofi, L.; Rossini, D.; Chiuminatto, U.; Stahl-Zeng, J.; Orlandini, S.; Furlanetto, S.; Bubba, M.D. Liquid chromatographic/electrospray ionization quadrupole/time of flight tandem mass spectrometric study of polyphenolic composition of different Vaccinium berry species and their comparative evaluation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kwon, R.H.; Kim, S.A.; Na, H.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, H.W. Characterization of anthocyanins including acetylated glycosides from highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) cultivated in Korea based on UPLC-DAD-QToF/MS and UPLC-Qtrap-MS/MS. Foods 2025, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, C.C. Ursolic acid and other pentacyclic triterpenoids: Anticancer activities and occurrence in berries. In Berries and Cancer Prevention; Stoner, G.D., Seeram, N.P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similie, D.; Minda, D.; Bora, L.; Kroškins, V.; Lugiņina, J.; Turks, M.; Dehelean, C.A.; Danciu, C. An update on pentacyclic triterpenoids ursolic and oleanolic acids and related derivatives as anticancer candidates. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zifkin, M.; Jin, A.; Ozga, J.A.; Zaharia, L.I.; Schernthaner, J.P.; Gesell, A.; Abrams, S.R.; Kennedy, J.A.; Constabel, C.P. Gene expression and metabolite profiling of developing highbush blueberry fruit indicates transcriptional regulation of flavonoid metabolism and activation of abscisic acid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, M.; Lukyanov, A.; Đurović, I.; Miletić, N. A novel method for analyzing the kinetics of convective/IR bread drying (CIRD) with sensor technology. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Viral status | Harvest year | |

| 2019 | 2020 | |

| BlMaV− | B19− | B20− |

| BlMaV+ | B19+ | B20+ |

| Month | Average Air Temperature (°C) |

Average Precipitation (mm) |

||

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| April | 11.7 | 10.5 | 166.8 | 70.0 |

| May | 13.1 | 14.1 | 110.2 | 197.2 |

| June | 20.4 | 17.7 | 328.4 | 231.0 |

| July | 20.1 | 19.4 | 107.2 | 17.4 |

| August | 21.3 | 20.6 | 71.2 | 46.6 |

| September | 16.5 | 17.2 | 2.4 | 49.6 |

| October | 12.4 | 11.8 | 5.4 | 152.6 |

| ANOVA | Blueberry samples | ||||

| B19− | B19+ | B20− | B20+ | ||

| Anthocyanins (mg/100 g fw) | ** | 112.06 ± 5.02b | 125.05 ± 7.09ab | 129.57 ± 5.51a | 134.34 ± 2.89a |

| Flavonoids (mg/100 g fw) | *** | 106.73 ± 2.45b | 101.45 ± 1.60c | 112.05 ± 0.52a | 108.68 ± 1.81ab |

| Phenols (mg/100 g fw) | ns | 325.26 ± 4.16 | 322.61 ± 6.49 | 324.64 ± 9.67 | 328.15 ± 4.49 |

| Antioxidativity capacity (μmol TE/100 g fw) |

ns | 77.03 ± 4.23 | 74.14 ± 3.99 | 73.34 ± 2.78 | 70.51 ± 6.28 |

| No. | Compounds name |

RT (min) |

Formula |

Calculated mass |

m/z exact mass |

mDa | Fragments (MS2) |

| Phenolic acids and derivatives | |||||||

| 1 | Methyl gallate | 5.64 | C8H7O5¯ | 183.0293 | 183.0295 | 0.15 | 124.0159(100), 125.019, 106.0054 |

| 2 | Caffeic acid hexoside | 5.50 | C15H17O9¯ | 341.0873 | 341.0865 | – 0.76 | 135.0444(100), 179.0338, 161.0228 |

| 3 | Dimethyl-digallate | 7.39 | C16H13O9¯ | 349.056 | 349.056 | 0.04 | 165.0183(100), 137.0236, 123.0081, 151.0028, 183.0297, 197.0445 |

| 4 | Caffeoylquinic acid is. I | 4.81 | C16H17O9¯ | 353.0873 | 353.0866 | – 0.66 | 191.0549(100), 135.0443, 179.0339, 161.0231, 173.0450, 127.0398, 111.0441 |

| 5 | Caffeoylquinic acid is. II | 6.34 | C16H17O9¯ | 353.0873 | 353.0866 | – 0.66 | 191.0550(100), 173.0446, 161.0235, 135.0444, 127.0395 |

| 6 | Caffeoylquinic acid is. III | 7.05 | C16H17O9¯ | 353.0873 | 353.0866 | – 0.66 | 191.0550(100), 173.0435, 161.0235, 127.0395, 111.0442 |

| 7 | Caffeoylquinic acid methyl ester | 7.65 | C17H19O9¯ | 367.1029 | 367.1026 | – 0.31 | 135.0446(100), 179.0342, 161.0234, 191.0551 |

| 8 | Tetramethyl-digallate | 9.07 | C18H17O9¯ | 377.0873 | 377.087 | – 0.26 | 165.0184(100), 137.0231, 121.0186, 151.0034, 190.9980, 315.0131, 330.0345, 166.0219 |

| 9 | Diferulic acid | 11.56 | C20H17O8¯ | 385.0923 | 385.092 | – 0.34 | 193.0491(100), 134.0366, 133.0302, 161.0230, 178.0253, 317.0350 |

| 10 | Caffeoyl coumaroylquinic acid | 8.77 | C25H23O11¯ | 499.124 | 499.1231 | – 0.94 | 163.0392(100), 191.0550, 173.0442, 155.0341, 135.0446, 119.0495, 337.0907, 179.0337 |

| 11 | Dicaffeoylquinic acid | 8.18 | C25H23O12¯ | 515.119 | 515.1183 | – 0.65 | 179.0339(100), 191.0550, 173.0445, 161.0233, 135.0444, 335.0766, 353.0860 |

| 12 | Caffeoylquinic acid dimer | 7.19 | C32H33O18¯ | 705.1667 | 705.1652 | – 1.49 | 513.1014(100), 339.0483, 191.0545, 321.0375, 495.0926 |

| Flavonol aglycones | |||||||

| 13 | Kaempferol | 10.22 | C15H9O6¯ | 285.0399 | 285.0397 | – 0.21 | 285.0390(100), 257.0425, 229.0488, 211.0404, 185.0587, 143.0528, 151.0064 |

| 14 | Quercetin | 9.50 | C15H9O7¯ | 301.0348 | 301.0345 | – 0.33 | 151.0029(100), 121.0290, 107.0135, 164.0109, 178.9975, 229.0487, 245.0438, 271.0234 |

| 15 | Isorhamnetin | 10.42 | C16H11O7¯ | 315.0505 | 315.0497 | – 0.78 | 300.0261(100), 151.0035, 107.0141, 137.0233, 164.0108, 178.9993, 203.0324, 227.0339, 259.0225 |

| 16 | Myricetin | 8.69 | C15H9O8¯ | 317.0297 | 317.0296 | – 0.14 | 151.0029(100), 137.0237, 107.0135, 125.0239, 165.0182, 178.9977, 227.0338, 243.0280, 271.0233 |

| 17 | Patuletin | 9.06 | C16H11O8¯ | 331.0454 | 331.0453 | – 0.09 | 243.0285(100), 299.0176, 271.0230, 255.0273, 227.0341, 215.0335, 199.0389, 183.0447, 171.0443, 143.0498 |

| 18 | Laricitrin | 9.58 | C16H11O8¯ | 331.0454 | 331.0453 | – 0.09 | 151.0044(100), 316.0206, 299.0171, 271.0230, 259.0236, 178.9978, 164.0104, 287.0184, 136.0160, 107.0132 |

| 19 | Syringetin | 10.38 | C17H13O8¯ | 345.061 | 345.0602 | – 0.84 | 315.0134(100), 287.0184, 330.0364, 345.0603, 301.0340, 259.0235, 271.0237, 203.0336, 151.0029 |

|

Flavonol glycosides and acyl derivatives |

|||||||

| 20 | Quercetin 3-O-pentoside | 8.16 | C20H17O11¯ | 433.0771 | 433.0767 | – 0.39 | 300.0259(100), 271.0234, 255.0289, 178.9989, 151.0032 |

| 21 | Myricetin 3-O-pentoside | 5.97 | C20H17O12¯ | 449.072 | 449.0714 | – 0.60 | 449.0702(100), 299.0172, 317.0280, 271.0215, 190.9972 |

| 22 | Quercetin 3-O-hexoside | 7.89 | C21H19O12¯ | 463.0877 | 463.0871 | – 0.55 | 300.0260(100), 301.0323, 463.0864, 271.0234, 255.0284, 151.0030, 178.9987 |

| 23 | Myricetin 3-O-hexoside | 7.44 | C21H19O13¯ | 479.0826 | 479.084 | 1.43 | 316.0207(100), 317.0261, 271.0234, 187.0184, 479.0810, 178.9980 |

| 24 | Laricitrin 3-O-hexoside | 8.06 | C22H21O13¯ | 493.0982 | 493.0977 | – 0.52 | 330.0365(100), 331.0419, 315.0133, 300.0260, 287.0514, 178.9973, 151.0039, 433.0758 |

| 25 | Quercetin 3-O-(6"-acetyl)hexoside | 8.49 | C23H21O13¯ | 505.0982 | 505.0978 | – 0.42 | 300.0262(100), 344.0518, 271.0234, 178.9974, 151.0025, 463.0861 |

| 26 | Syringetin 3-O-hexoside | 8.39 | C23H23O13¯ | 507.1139 | 507.1125 | – 1.37 | 344.0521(100), 507.1112, 345.0574, 387.0699, 329.0300, 316.0569, 301.0403, 273.0381, 151.0031 |

| 27 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-(6"-acetyl)hexoside | 8.99 | C24H23O13¯ | 519.1139 | 519.113 | – 0.87 | 314.0418(100), 519.1125, 315.0462, 299.0203, 285.0393, 271.0241, 257.0443, 243.0289, 151.0025, 357.0595 |

| 28 | Quercetin 3-O-(6"-O-rhamnosyl)hexoside (like Rutin) | 7.74 | C27H29O16¯ | 609.1456 | 609.145 | – 0.56 | 300.0261(100), 609.1435, 301.0329, 271.0235, 151.003, 178.9975, 343.0431 |

| 29 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-(6"-O-rhamnosyl)hexoside (like Narcissin) | 8.22 | C28H31O16¯ | 623.1612 | 623.1608 | – 0.41 | 315.049(100), 623.1592, 314.0416, 300.0249, 271.0241, 151.0022, 357.0595 |

| Other phenolic compounds | |||||||

| 30 | Naringenin | 10.04 | C15H11O5¯ | 271.0606 | 271.0603 | – 0.35 | 119.0499(100), 107.0132, 151.0024, 161.0590, 187.0388, 229.0458, 245.0477 |

| 31 | Vanilloloside | 3.95 | C14H19O8¯ | 315.108 | 315.108 | 0.01 | 123.0445(100), 153.0547, 124.0478 |

| 32 | Procyanidin B-type dimer (like Procyanidin B2) | 6.04 | C30H25O12¯ | 577.1346 | 577.1335 | – 1.10 | 289.0700(100), 407.0752, 125.0237, 137.0243, 161.0241, 245.0796, 273.0388, 339.0842, 381.0951, 425.0876, 451.1001 |

| Anthocyanins | |||||||

| 33 | Delphinidin 3-O-pentoside | 6.47 | C20H19O11⁺ | 435.0927 | 435.0919 | – 0.84 | 303.0488(100), 304.0523, 305.0543 |

| 34 | Petunidin 3-O-pentoside | 6.74 | C21H21O11⁺ | 449.1084 | 449.1075 | – 0.89 | 317.0644(100), 318.068, 287.0535, 302.0409 |

| 35 | Malvidin 3-O-pentoside | 7.07 | C22H23O11⁺ | 463.124 | 463.1232 | – 0.84 | 331.0802(100), 332.0835, 301.0695, 315.0488, 287.0534 |

| 36 | Delhinidin 3-O-hexoside | 6.19 | C21H21O12⁺ | 465.1033 | 465.1025 | – 0.80 | 303.0488(100), 304.0522, 305.0543 |

| 37 | Petunidin 3-O-hexoside | 6.6 | C22H23O12⁺ | 479.119 | 479.1182 | – 0.75 | 317.0645(100), 318.0677, 302.0409 |

| 38 | Malvidin 3-O-hexoside | 6.93 | C23H25O12⁺ | 493.1346 | 493.1338 | – 0.8 | 331.0802(100), 332.0835, 315.0486, 287.0536 |

| 39 | Peonidin 3-O-(6"-acetyl)hexoside | 7.8 | C24H25O12⁺ | 505.1346 | 505.1343 | – 0.30 | 301.0692(100), 302.0731, 303.0702, 286.0457 |

| 40 | Delphinidin 3-O-(6"-acetyl)hexoside | 7.32 | C23H23O13⁺ | 507.1139 | 507.1131 | – 0.77 | 303.0487(100), 304.0521, 305.0547 |

| 41 | Petunidin 3-O-(6"-acetyl)hexoside | 7.48 | C24H25O13⁺ | 521.1295 | 521.1286 | – 0.92 | 317.0643(100), 318.068, 302.0406 |

| 42 | Malvidin 3-O-(6"-acetyl)hexoside | 7.68 | C25H27O13⁺ | 535.1452 | 535.1444 | – 0.77 | 331.0801(100), 332.0835, 315.0486 |

| Other compounds (Terpenoids) | |||||||

| 43 | Pentacyclic terpenoid (like Maslinic or Pomolic acid) | 14.79 | C30H47O4¯ | 471.3474 | 471.3472 | -0.23 | 471.3460(100), 453.3342, 427.3566, 409.3457 |

| 44 | Pentacyclic terpenoid I (like Arjunolic, Euscaphic or Rotundic acid) | 12.58 | C30H47O5¯ | 487.3423 | 487.3415 | -0.85 | 487.3396(100), 469.3305, 437.3053, 425.3392, 405.3107, 393.3127, 443.3483 |

| 45 | Pentacyclic terpenoid II (like Arjunolic, Euscaphic or Rotundic acid) | 12.92 | C30H47O5¯ | 487.3423 | 487.3415 | -0.85 | 487.3405(100), 469.3288, 425.3394, 407.3258, 443.3536, 393.3111 |

| Other compounds (Plant hormone) | |||||||

| 46 | Abscisic acid | 9.31 | C15H19O4¯ | 263.1283 | 263.1283 | -0.03 | 203.1068(100), 219.1372, 289.0910, 153.0911, 136.0521, 122.0367, 125.0605, 148.0525 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).