1. Introduction

Quantum many-body problems rarely allow full analytic solutions and typically are also prohibitively hard to solve numerically. A plethora of expansion methods have thus been developed to study them approximately. In particular, when one expects some convergence to their classical counterparts in a large number limit, the first quantum corrections appearing are of central interest. Beyond a first-order mean field expansion [

1], the quantum cumulants expansion is one of the most widely used methods to study the influence of quantum correlations in many-body physics [

2]. It proves very successful in studies of photon statistics and quantum correlations in various light sources, starting with the first successful model description of a laser or even non-classical light sources as few-photon emitters [

3]. Despite its success in solving concrete practical approximations, hardly any detailed studies on its convergence when applying higher order expansions exist [

4,

5]. Mostly, second-order calculations, including pair correlations, proved sufficient. Systematic numerical studies in this direction are often hampered by a lack of analytically solvable nonlinear and nontrivial many-body dynamics models, where convergence could be thoroughly studied in a quantitative fashion.

Luckily, many decades after the prediction of superradiance [

6] and clear experimental evidence [

7], a tractable analytical solution for the seminal problem of free space Dicke superradiance has been recently put forward [

8,

9]. This new analytic form of the solution beyond the single spin quantum Rabi model [

10] allows us to obtain highly accurate solutions for very large atom numbers, way beyond any direct numerical solution of the master equation. As high-order correlations build up during the time evolution of superradiant decay, this gives an ideal reference frame for a systematic test of the cumulant expansion for high quantum emitter numbers.

Here we can use the established quantum cumulant approach [

11] to generate high-order expansions and study the convergence of key quantities, such as the peak emitted power or the time of maximum emission, as well as higher-order photon correlations. While no quantum entanglement builds up in pure superradiant decay [

12], a closely related recent study exhibited the buildup of dipole correlations, particularly in the early phase of superradiance [

13]. This shows the need for higher-order corrections beyond a field expansion, which misses all correlations. The early time phase correlation buildup starting from a random first emission event typically leads to a significant variance of the time when the intensity maximum occurs, if one unravels the evolution in single wavefunction trajectories [

14].

Interestingly, while most of the individual stochastic trajectories exhibit highly non-classical, entangled intermediate states [

15], this property is finally completely washed out by ensemble averaging. Efforts to reproduce the vanishing trajectory averaged entanglement using a stochastic unraveling, thus prove numerically very intensive. The buildup of spin correlations, however, appears automatically when evaluating the second-order cumulant as introduced below. A comparison of the exact result versus the predictions of a truncated cumulant expansion can then reveal the importance of even higher-order correlations.

This work is organized as follows: After the introduction of the Dicke model and the resulting master equation in the individual and collective bases, we define and present the corresponding two forms of the cumulant expansion in the two operator basis sets. As the first test, we study the convergence of a cumulant expansion of the collective Spin operators to the exact results for increasing expansion order. For smaller atom numbers, we then study the convergence properties of an individual spin-based expansion, for which the expansion gets exact once the order reaches the number of spins. We then compare the two expansion methods for larger ensembles, followed by a more detailed analysis of error scaling with numbers and order for the two methods.

2. Theoretical Description

2.1. Quantum Master Equation

The Dicke superradiance problem involves finding the density operator

which satisfies the following master equation in Lindblad form (in an interaction picture where the trivial action of the free Hamiltonian is removed):

where

is the jump operator for emitter

n and

is the symmetric jump operator in the Dicke basis [

6]. Note that besides the number of emitters

N, we are left with only one parameter

, which simply sets the time scale.

We will calculate the averaged total emitted power and excited state population, given by (setting

)

as a figure of merit using both the full master equation in the symmetric Dicke subspace and using the cumulant expansion method, explained below.

2.2. Equations of Motion for Expectation Values of Operators

Let us further define a general operator

with expectation value

. Then, its dynamics are given by

Throughout this work we assume, that the system is initialized in the uncorrelated product state

and using Eq.

3 we start noticing that

,

,

(for

) and so forth, namely terms

have to appear simultaneously. We are interested in the time evolution of the system operators, which leads to a coupled set of equations with increasing order in the operator correlations, namely

where

. The computational complexity of the coupled set of equations scales polynomially with correlation order

r as

. In order to obtain a closed set of equations and render the system numerically tractable, the correlations have to be truncated, which can be done systematically using the cumulant expansion method [

16], explained in the next section.

3. Cumulant Expansion Method

In order to stop the hierarchy of equations above from expanding and close the system of equations, we need to apply a systematic cumulant expansion on the operator averages:

In order to obtain a closed set of equations, only correlations up to a certain order are considered, while all higher-order correlations are expanded in terms of lower orders. This approximation can be computed in a systematic fashion, using the cumulant expansion. The joint cumulant of an

Mth-order correlation

can be expressed as an alternate sum of products of their expectation values and is compactly written as [

16]

where

runs through the list of all partitions of

,

B runs through the list of all blocks of the partition

and

is the number of parts in the partition. An approximation can be made by setting

, which allows to express

with correlations of order

and lower. For instance, the expansion of expectation values involving three operators reads

This introduces some error, as all higher-order correlations are neglected. In the following sections, we will quantitatively analyze this error based on the truncation order and number of emitters.

4. Benchmarking Cumulant Expansion Convergence

Let us now proceed to test the accuracy and convergence of the cumulant expansion approximation to predict collective superradiant decay for increasing cumulant expansion order, i.e., setting the -order cumulant to zero for increasing M.

Before going into details, however, let’s note that in the chosen Dicke limit [

17] of all atoms well within a cubic wavelength and neglecting dipolar energy shifts, there is actually only a single interesting physical parameter, namely the total atom number

N entering the exact dynamics. The other free parameter

is the single-atom decay rate (proportional to the square of the dipole moment), which only fixes the overall time scale. It does not change the results in any other way. Of course, for any finite extent or nonspherical shape of the cloud as well as for any imperfect excitation of the ensemble, many more details of the geometry will enter [

18]. While these corrections will somewhat change the actual numbers, we will ignore them here for the sake of clarity of the arguments.

4.1. Time Evolution

Let us start with a comparison of the predicted time evolution of the full ensemble and use key quantities as the total remaining excited state population as well as the momentarily emitted power in Eq.

2 for benchmarking the cumulant expansion versus the full density matrix evolution. In a first step, we choose only two representative system sizes from small

to large

. In a further step below, we will then compare characteristic quantities as the time and magnitude of the maximal emitted power, as key average properties to characterize the reliability of the approximations over many orders of magnitude of atom numbers.

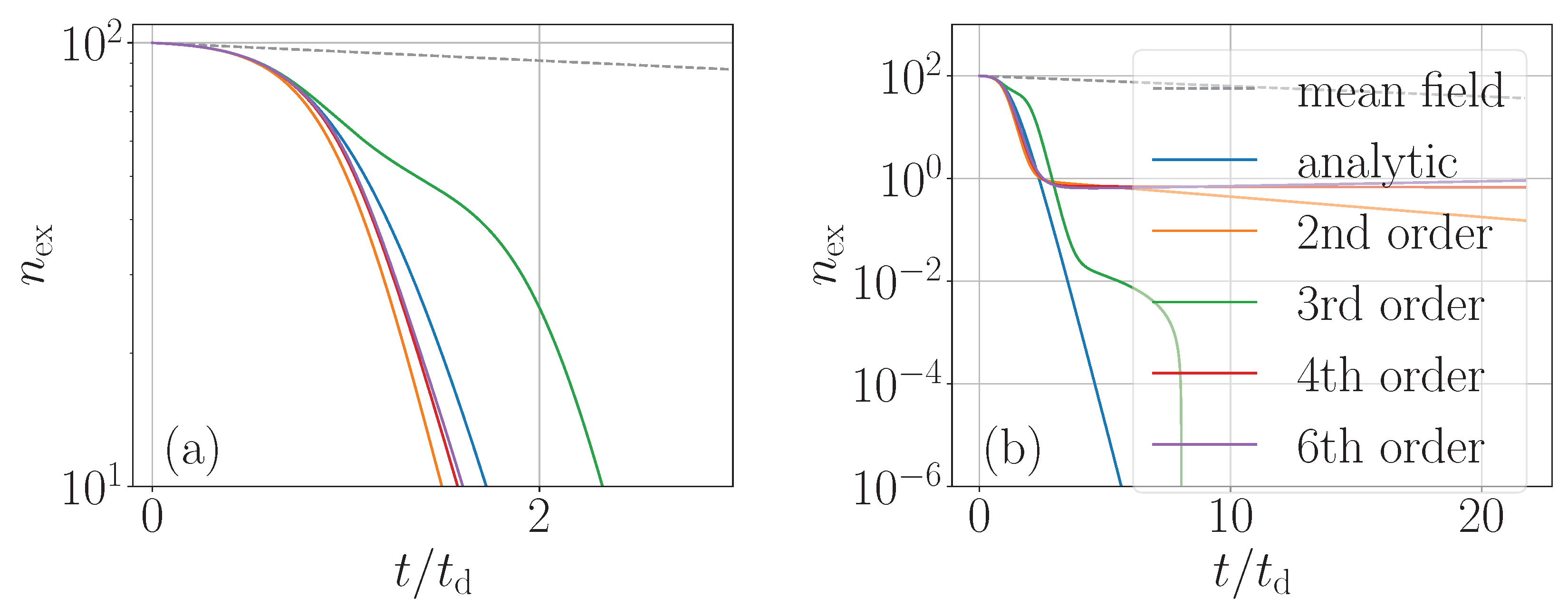

In

Figure 1 we depict the population decay of an average-sized ensemble of

emitters in units of the analytically predicted time of maximal emission power. On the left, we show the evolution till the time where

of the atoms have decayed, comparing different expansion orders. We only find a quantitatively good agreement for times before maximum emission. Strong deviation from the exact results appears in particular for odd orders at later times. Let us add here that the first-order expansion (mean field) fails from the beginning, as it simply reproduces individual (exponential) decay with no buildup of collective dynamics. This is shown in the straight uppermost dashed line. We see that in this time range, even orders slowly converge to the exact result, already diverging by about 10% for the prediction of the time when only 10% of the initial population is left in the ensemble.

For longer times, where the remaining population has decayed to less than one percent, the cumulant expansion simply fails to correctly reproduce the decay process. Somewhat surprisingly, no convergence towards the exact dynamics appears even for higher-order calculations. The predicted decay curves from the truncated expansion generally exhibit a rather nonphysical long-lived population fraction.

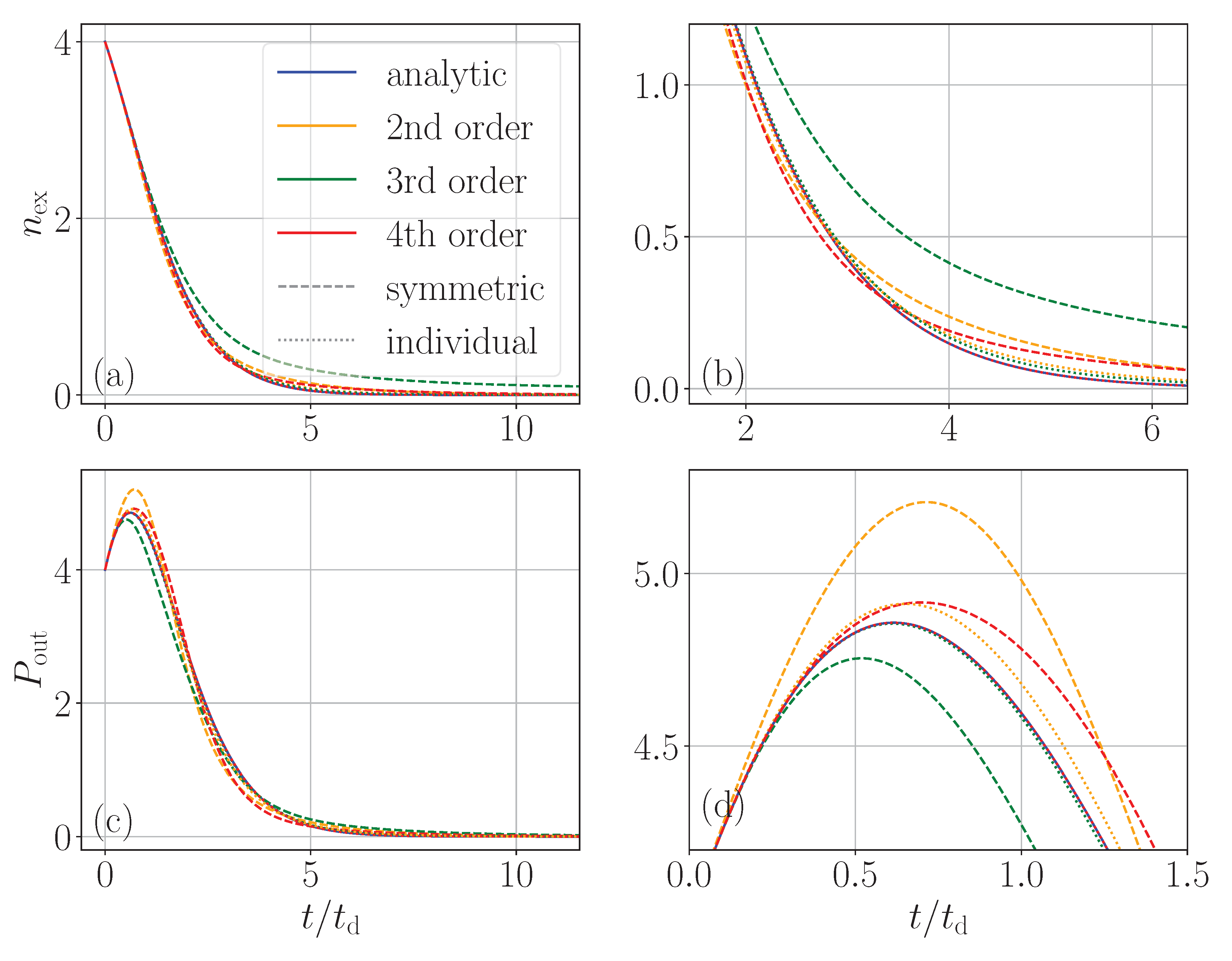

It is well known that the cumulant expansion approximation of interacting spins becomes exact when the order reaches the number of spins [

16]. Hence, in the next step, we look at the small number of only 4 spins to study the cumulant convergence as shown in

Figure 2. Indeed, the 4

th-order represented by exactly the same set of coupled equations used above for the case of

now behaves indistinguishably from the exact result based on solving the full master equation. Again, as above, the 3

rd-order expansion exhibits a worse agreement than the 2

nd-order. Interestingly, the individual spin-based expansion here converges very well and way better than the symmetric collective approach.

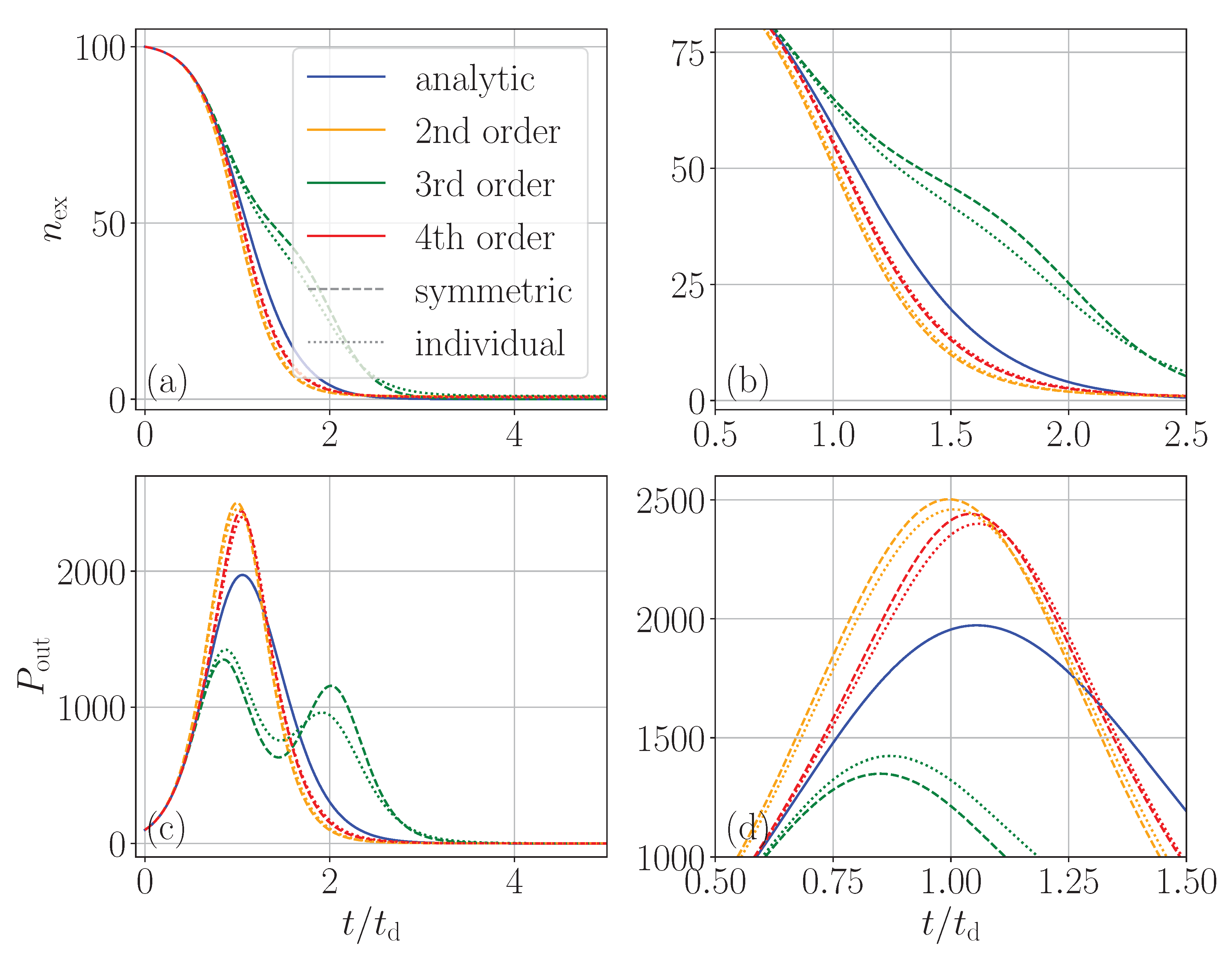

As we will see below in more detail, the convergence difference between individual and collective spim cumulants strongly reduces with sample size, but while the two methods converge to each other, they still significantly deviate from the exact numerical result. In

Figure 3 we highlight this for the case of

emitters. While the two approaches only differ on a few percent level at a later time, there are even qualitative deviations from the exact dynamics. In particular, we see a clearly nonphysical double peak structure in the emission power depicted on the lower left for the 3

rd-order cumulant expansion. On the lower left (zoomed plot), we see a better agreement of the various approaches at least until the time of maximum emission. It remains a bit unclear to us where this curious behavior originates, but it seems to be related to the crossing of the equator in the Bloch sphere, where dynamics change from synchronization to dephasing of the individual spins. This might lead to erroneous three-spin correlations, which need non-trivial four-spin correlations as correction factors. Overall, it is a strong reminder that the cumulant expansion beyond second order needs to be taken with great care.

4.2. Peak Emission Time and Power

After highlighting some key properties of the time evolution, we now come to a more systematic quantitative analysis of the system size scaling. For this, we choose two central observables in the dynamics, namely time and power of the maximum mission peak. This allows us to compare the quantitative accuracy of various orders of our two cumulant approaches (individual or collective spin basis) as a function of system size

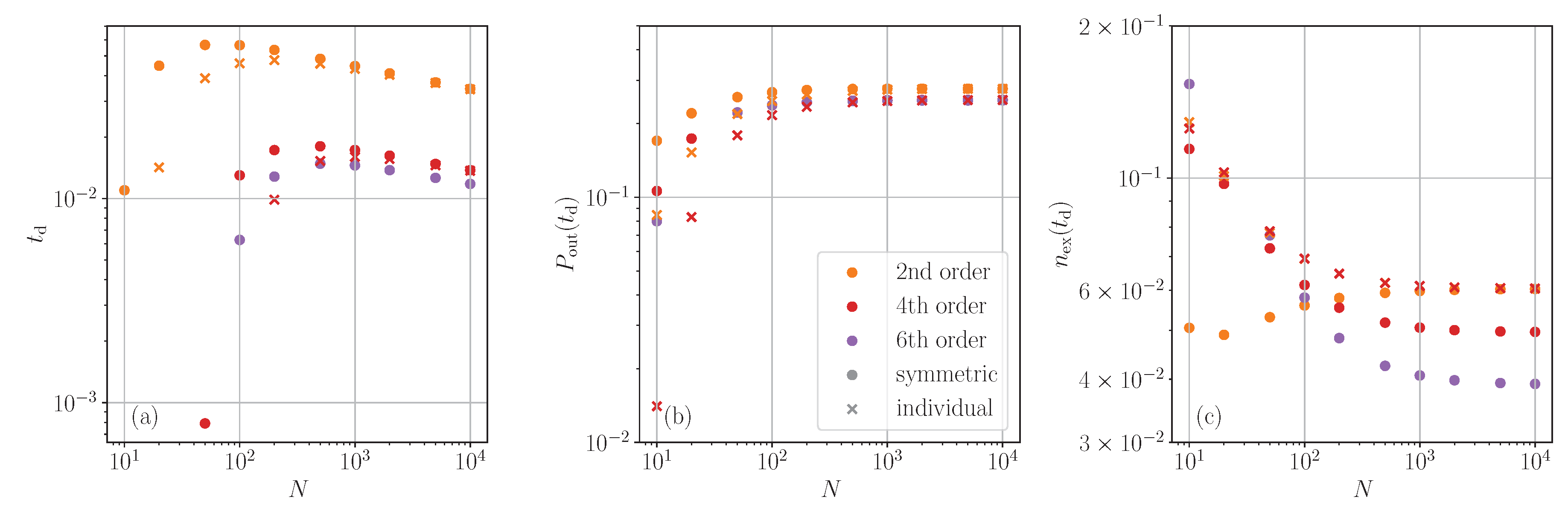

N. In

Figure 4 on the left, we plot the relative deviation of the predicted time of maximum emission from the exact value. It appears promising that already the second order cumulant expansion yields results accurate to better than 5%, which somewhat slowly improves with emitter number. The 4

th-order is more accurate and converges towards a 1% error for large ensembles. Again, the individual operator-based expansions behave consistently superior, particularly for smaller

N.

The prediction for maximal power shown in the middle is somewhat less accurate and converges only to the few percent level for large N. Surprisingly, higher-order corrections do not substantially improve the prediction.

Looking at the remaining upper state population at maximum emission time plotted in the right panel of

Figure 4, we find a similar percent level accuracy. However, in this case, we find significant improvement for larger ensembles, and a higher-order expansion significantly improves the prediction. As already seen in the time evolution plots above, the third order turns out to be very unreliable even at this rather short evolution time. Again, a second-order expansion using individual operators turns out to be a fairly good and reliable approximation over all system sizes.

Figure 4.

Relative error of increasing cumulant expansion orders compared to the full quantum time evolution (based on exact numerics using the master equation) for the characteristic quantities of superradiance as the time of maximal emission (left), the maximal emission power (middle), and the average atomic population at the power maximum (right). One generally finds deviations at the percent level with some improvement with expansion order from 2nd-order (orange), via fourth order (red) to 6th-order (purple). The individual operator-based expansions (crosses) are more reliable than the collective operator cumulants (dots), in particular at small system sizes.

Figure 4.

Relative error of increasing cumulant expansion orders compared to the full quantum time evolution (based on exact numerics using the master equation) for the characteristic quantities of superradiance as the time of maximal emission (left), the maximal emission power (middle), and the average atomic population at the power maximum (right). One generally finds deviations at the percent level with some improvement with expansion order from 2nd-order (orange), via fourth order (red) to 6th-order (purple). The individual operator-based expansions (crosses) are more reliable than the collective operator cumulants (dots), in particular at small system sizes.

In summary, we see that the quality and usefulness of the cumulant expansions strongly depend on the targeted observable and deteriorate for longer time scales. In general, going beyond the second order is hardly worth the effort, as some minor improvements come with a much more complex set of equations to solve. On the other hand, several important quantities, such as intensity correlations or spectra, require higher-order observables anyway. The rather poor long-time behaviors also hint that steady state calculations can be rather problematic, even if one finds a numerical solution of the nonlinear coupled set of equations.

5. Conclusions

It is well known that for the perfectly inverted initial state, i.e., all emitters in the excited state, in the Dicke model, a first-order mean field approximation completely fails, as no coherence dipole-dipole correlations are accounted for [

19]. Here, we have demonstrated that a second-order cumulant expansion produces a fairly reliable approximation to the full superradiant decay, in particular for higher atom numbers and up to intermediate times. Surprisingly, higher-order expansions generally only lead to minor improvements even in the best case. Actually, the third and fifth order expansions often exhibit physically wrong oscillatory solutions on intermediate time scales. Interestingly, two possible variants of the cumulant expansion, based either on individual atomic spin operators or as an alternative based on the collective spin basis, lead to different predictions beyond mean field. Note that in the full quantum limit, these two approaches exactly agree, as it just corresponds to a different choice of computational basis.

For not too large numbers, the first case of using a many-particle cumulant expansion leads to significantly higher accuracy and even converges to the exact result, when the order approaches the particle number. The differences between the two basis models, fortunately, vanish in the large N limit.

In summary, we see that a cumulant expansion to second order can capture a large part of the deviation from classical to quantum dynamics, while the usefulness of higher order expansions is rather limited. In particular, due to the much larger number of equations to be solved, the extra effort hardly pays off. Of course, 4th-order expansions are still required to obtain higher order correlation functions such as the -function for intensity correlations. These results, however, have to be taken with some care.

6. Supplement

Closed Set for Equations of Motion

Here we explicitly show the equations of motion up to second order after application of the cumulant expansion method. The operator equations of motion read

Acknowledgments

We thank Klemens Hammerer for helpful comments and suggestions. Numerical calculations were performed based on the QuantumCumulants.jl [

11] package. We acknowledge support from the (FWF) doctoral college DK-ALM W1259-N2 and the COE1 QuantA.

References

- Bogoliubov, N.N. Problems of Dynamical Theory in Statistical Physics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1960.

- van Kampen, N.G. A cumulant expansion for stochastic linear differential equations. Physica 1974, 74, 215–238. [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, R.; Moreno-Cardoner, M.; Ritsch, H. Nanoscale continuous quantum light sources based on driven dipole emitter arrays. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 119, 024002. [CrossRef]

- Brey, L.; Prange, R.E. Cumulant expansion for the density matrix in quantum statistical mechanics. Physical Review B 1984, 30, 2581–2587.

- Kira, M.; Koch, S.W. Cluster-expansion representation in quantum optics. Physical Review A 2006, 73, 013813. [CrossRef]

- Dicke, R.H. Coherence in Spontaneous Radiation Processes. Phys. Rev. 1954, 93, 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Roof, S.; Kemp, K.; Havey, M.; Sokolov, I. Observation of single-photon superradiance and the cooperative Lamb shift in an extended sample of cold atoms. Physical review letters 2016, 117, 073003.

- Holzinger, R.; Genes, C. A compact analytical solution of the Dicke superradiance master equation via residue calculus. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A 2025, 80, 673–679. [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, R.; Bassler, N.S.; Lyne, J.; Jimenez, F.G.; Gohsrich, J.T.; Genes, C. Solving Dicke superradiance analytically: A compendium of methods, 2025, [arXiv:quant-ph/2503.10463].

- Braak, D. Integrability of the Rabi Model. Physical Review Letters 2011, 107, 100401. [CrossRef]

- Plankensteiner, D.; Hotter, C.; Ritsch, H. QuantumCumulants.jl: A Julia framework for generalized mean-field equations in open quantum systems. Quantum 2022, 6, 617. [CrossRef]

- Bassler, N.S. Absence of Entanglement Growth in Dicke Superradiance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.13646 2025.

- Zhang, X.H.; Malz, D.; Rabl, P. Unraveling superradiance: entanglement and mutual information in collective decay. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.13401 2025.

- Clemens, J.P.; Carmichael, H. Stochastic initiation of superradiance in a cavity: an approximation scheme within quantum trajectory theory. Physical review A 2002, 65, 023815.

- Hotter, C.; Kosior, A.; Ritsch, H.; Gietka, K. Conditional atomic cat state generation via superradiance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.11542 2024.

- Kubo, R. Generalized Cumulant Expansion Method. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 1962, 17, 1100–1120. [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Haroche, S. Superradiance: An essay on the theory of collective spontaneous emission. Physics Reports 1982, 93, 301–396. [CrossRef]

- Gorlach, A.; Pizzi, A.; Mølmer, K.; Avron, J.; Segev, M.; Kaminer, I. Supercoherence: Harnessing Long-Range Interactions to Preserve Collective Coherence in Disordered Systems, 2025, [arXiv:quant-ph/2508.06238].

- Ostermann, L.; Meignant, C.; Genes, C.; Ritsch, H. Super- and subradiance of clock atoms in multimode optical waveguides. New Journal of Physics 2019, 21, 025004. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).