1. Introduction

Melanoma is a highly aggressive form of skin cancer originating from melanocytes, accounting for the majority of skin cancer-related deaths despite representing a small fraction of skin cancer cases overall [

1]. Moreover, the mortality rate of melanoma is predicted to rise in the coming decades. [

2].

Traditional treatment strategies, including surgery, immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, have significantly improved patient outcomes, especially in early-stage disease. However, advanced melanoma remains challenging to treat due to its propensity for metastasis and resistance to conventional therapies [

3]. Furthermore, current standard therapies are often limited by issues such as off-target effects, systemic toxicity, invasive procedures, suboptimal drug penetration, low bioavailability, low survival rates, and high treatment costs [

4]. These limitations contribute to poor survival rates in advanced cases and underscore the critical need for more effective, selective, and minimally invasive treatment strategies.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a minimally invasive treatment that involves administering a photosensitizing agent (PS), which preferentially accumulates in tumor cells, followed by activation with a specific wavelength of light [

5,

6]. This activation subsequently induces a cascade of photochemical reactions, culminating in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS is capable of causing direct cytotoxic effects and destroying malignant cells by inducing apoptosis and necrosis [

7]. PDT is distinguished by its targeted approach, minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues, and minimal long-term side effects [

8]. However, conventional PDT in melanoma faces significant limitations. The high optical absorption and scattering of melanin within melanoma cells often reduce the penetration of visible light and thus attenuate treatment efficacy. Furthermore, standard photosensitizers can have poor activation in pigmented tissues, leading to suboptimal results [

9,

10,

11]. These challenges have prompted exploration of alternative light sources, activation strategies, and novel photosensitizers to enable PDT in difficult-to-treat, deeply seated, or pigmented tumors.

Photosensitizers play a vital role in PDT. These molecules should have high singlet oxygen quantum yields, be rapidly removed from the patient’s body, have low activity in the absence of light, selectively accumulate in tumor tissue, and have amphiphilicity [

12,

13]. Copper-cysteamine (Cu-Cy) nanoparticles (NPs) are one type of radiosensitizers that are able to be activated by diverse energy sources, including ultraviolet (UV) light, X-rays, microwaves, ultrasound, as well as tumor microenvironment factors such as acidic pH and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). This multimodal activation triggers ROS production, allowing effective tumor cell killing in vitro and in animal models. Their selective uptake by tumor cells and significant phototoxicity, combined with minimal toxicity in the absence of irradiation, make them particularly suited for PDT in melanoma [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, using UV light as the activating source, Cu-Cy NPs have shown versatility for superficial and accessible melanoma lesions, potentially overcoming some of the classical limitations associated with deeper or pigmented tumors [

20].

The integration of Cu-Cy NPs into PDT protocols specifically activated by UV light represents an innovative and promising therapeutic strategy for melanoma. Considering that many aspects of this nanoparticle remain unknown, in this study, we aim to investigate the synergistic effect of UV radiation on Cu-Cy NPs on A375 cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

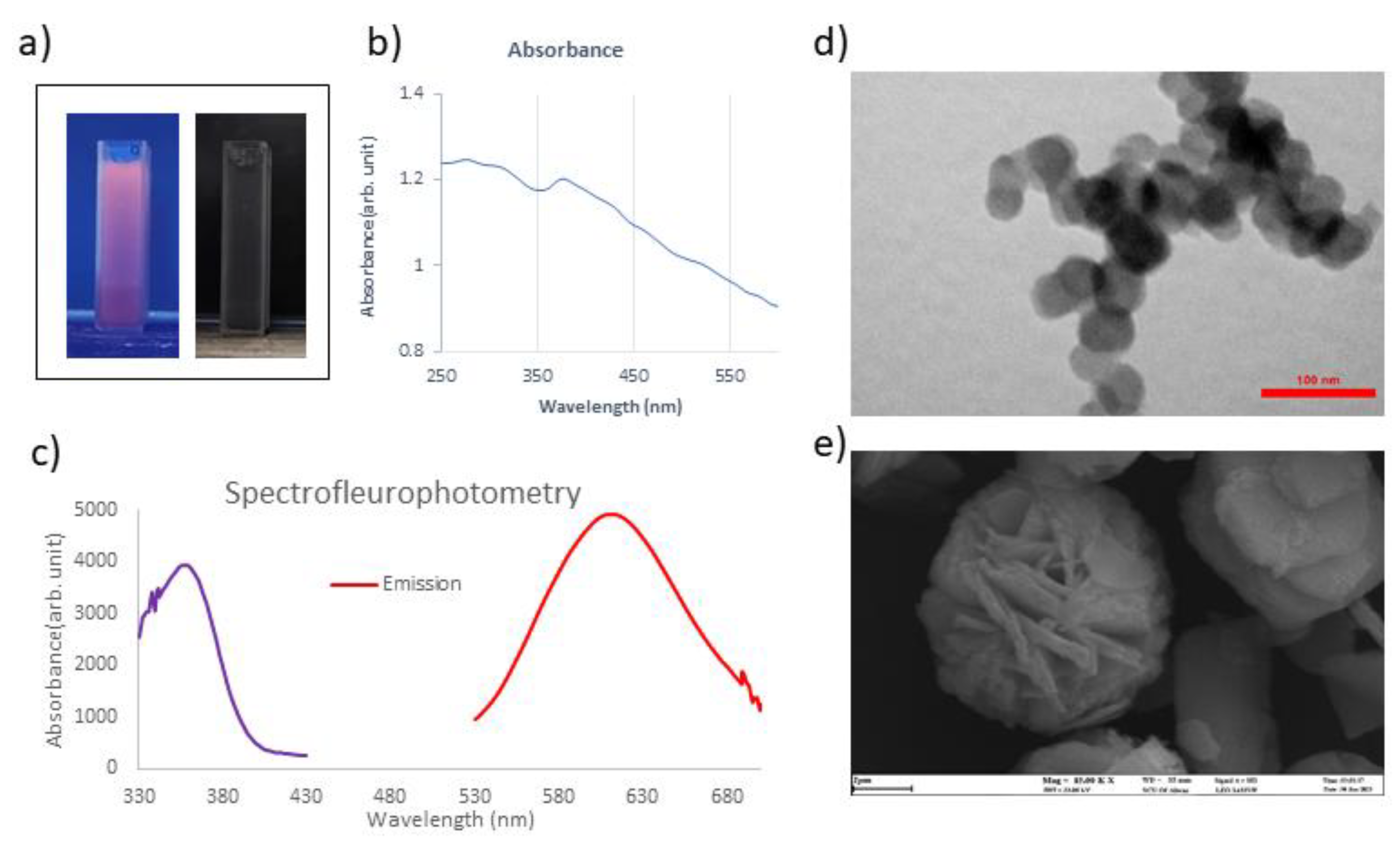

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Cu-Cy NPs:

Cu-Cy NPs have been synthesised using the method described by Pandey et al., with some modifications [

21]. The photoluminescence of the nanoparticles under a UV-365 nm lamp was the main property investigated to confirm their successful synthesis. The excitation and emission spectra were recorded using a spectrofluorophotometer (Thermo Scientific Lumina), and UV-Visible spectroscopy was performed with a spectrophotometer (Photonix Ar 2015). Imaging of Cu-Cy crystals was performed using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Leo 1455VP), and the Cu-Cy NPs were obrained using a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) (LEO 906E).

2.2. Exploring the Synergistic Effect of Cu-Cy NPs and UV

2.2.1. Cell Culture

A375, a human melanoma cell line, was obtained from Geniranlab in Tehran, Iran. Cells were cultured at a temperature of 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, utilizing Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

2.2.2. UV Irradiation

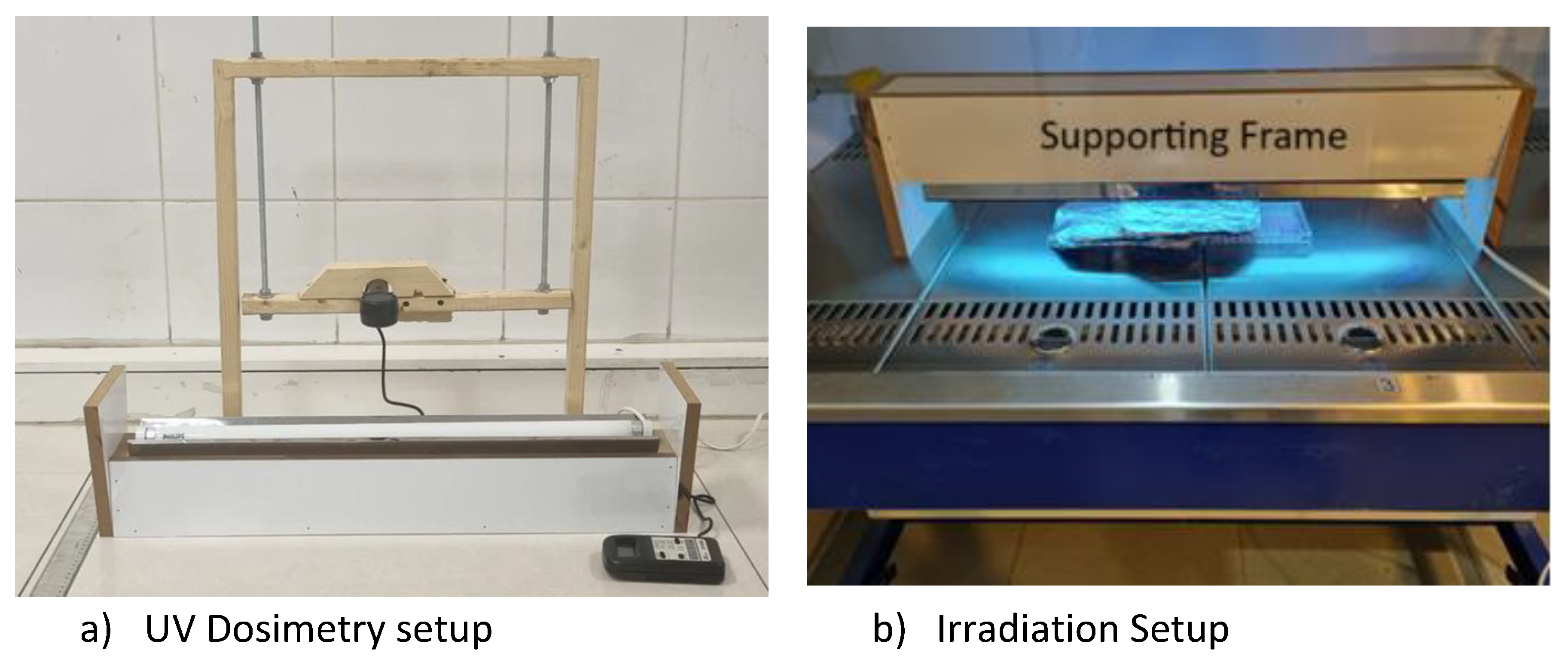

In this study, an ultraviolet A (UVA) lamp (Philips, ACTINIC BL, TL-D 18W, Poland) with a peak emission at 360 nm (dimensions: 589.8 mm length × 28 mm diameter) was used to irradiate melanoma cells. As illustrated in

Figure 1. a, dosimetry was performed at varying distances using a UV-340 light meter (Lutron, Taiwan). Each measurement was taken over a five-minute exposure period. During irradiation experiments, a fixed 5 cm distance between the lamp and the cell culture plate was maintained using a specially fabricated support frame, as shown in

Figure 1-b.

2.2.3. MTT Viability Assay

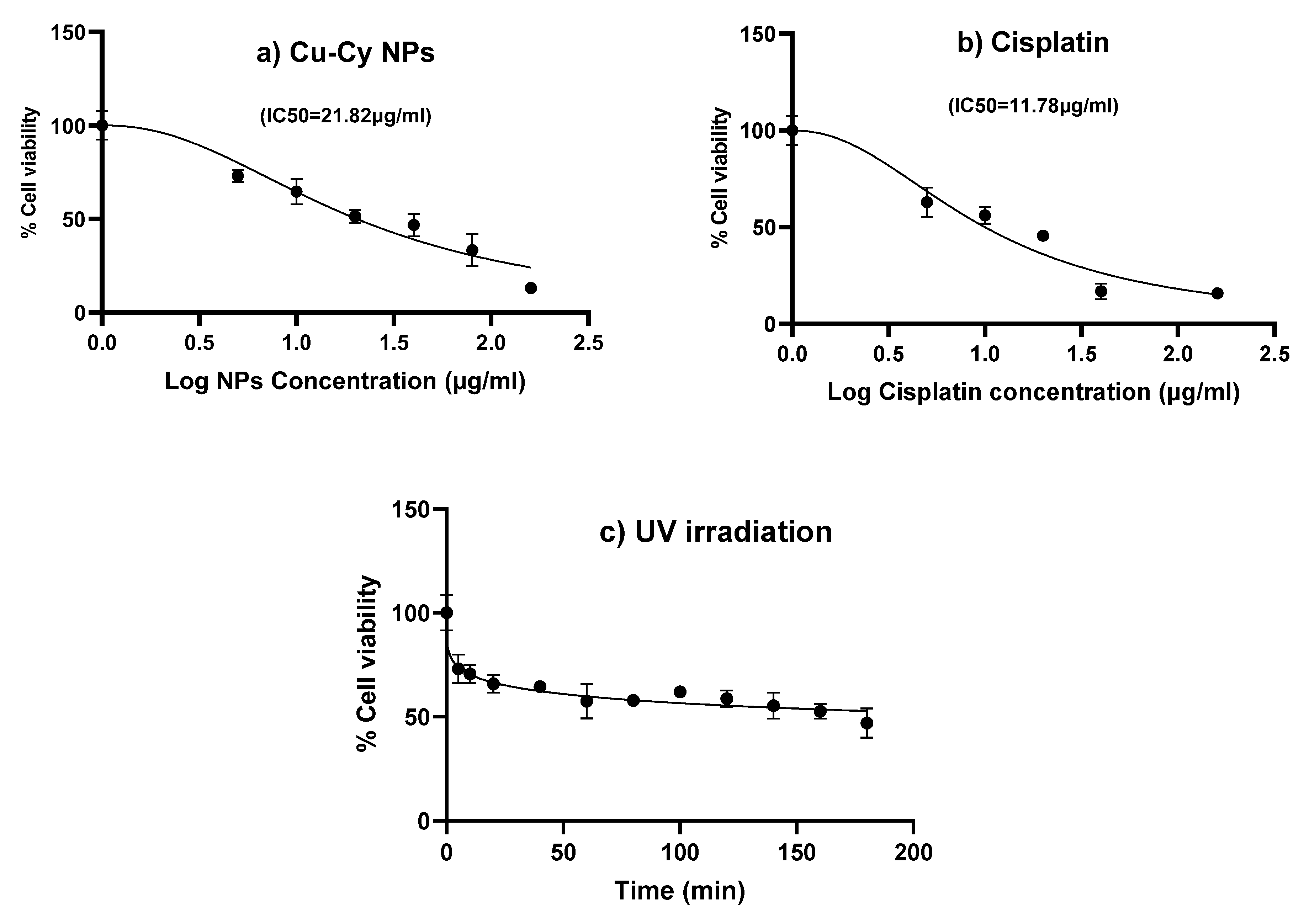

To evaluate the cytotoxic effect of Cu-Cy NPs, 8 × 10³ cells/well were seeded in a 96-well plate. After 24 hours of incubation, the cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Cu-Cy NPs (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μg/mL) for 24 hours. In parallel, cells were exposed to varying doses of cisplatin (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160 μg/mL) as a positive control, owing to its well-established dose-dependent cytotoxicity. Additionally, to determine the optimal irradiation time for UVA exposure, the cells were subjected to different durations of UVA irradiation (0–180 minutes). Cell viability was evaluated 24 hours after exposure.

For all experiments, the culture medium was removed and replaced with 100 μL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) in each well. Following a 4-hour incubation, wells were gently washed with PBS, and 100 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad 680 ELISA Reader).

The IC₅₀ value for cisplatin, corresponding to approximately 50% cell death, was determined from the dose–response curve and used as a positive control in subsequent assays. For Cu-Cy NPs, a concentration of 3 μg/mL was selected, and UVA exposure times of 2 and 10 minutes were applied to evaluate potential synergistic effects. These parameters were used in follow-up ROS and apoptosis analyses.

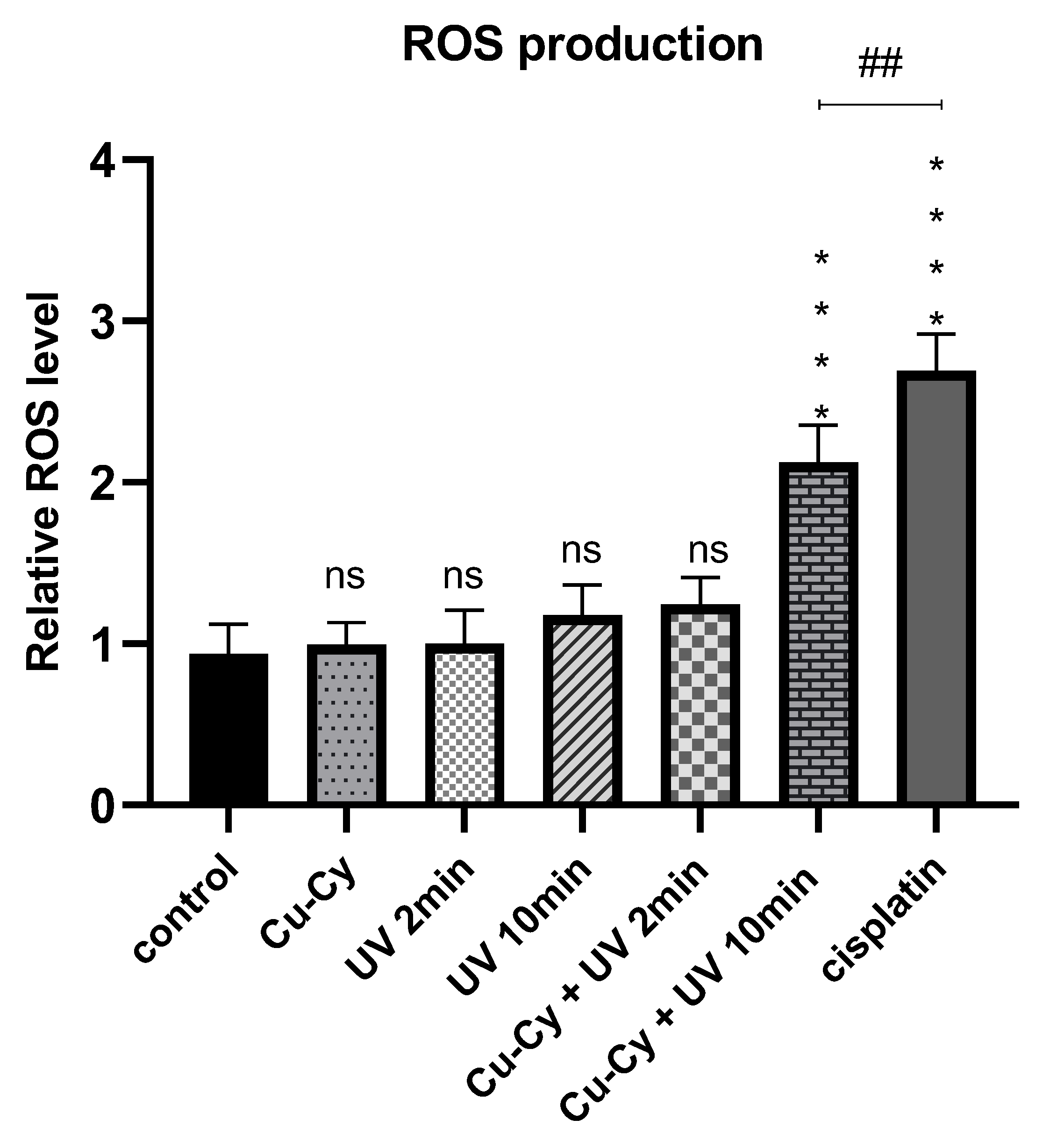

2.2.4. Assessment of Intracellular ROS Generation Using the NBT Assay

ROS generation was evaluated using the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) assay (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). A375 cells (8 × 10³ cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 hours under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂, humidified atmosphere). The cells were then treated according to the following experimental groups: control, UVA irradiation (2 and 10 minutes), Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL), combination of Cu-Cy NPs with UVA (3 μg/mL + 2 or 10 minutes), and cisplatin (11.87 μg/mL) as a positive control. After 24 hours of treatment, cells were incubated with NBT solution (1 mg/mL) for 2 hours, while plates were protected from light using aluminum foil. Following incubation, the NBT solution was removed, and wells were gently washed with 100 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 100 μL of 2 M potassium hydroxide (KOH), followed by 100 μL of DMSO. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad 680 ELISA Reader), providing a quantitative measure of intracellular ROS levels.

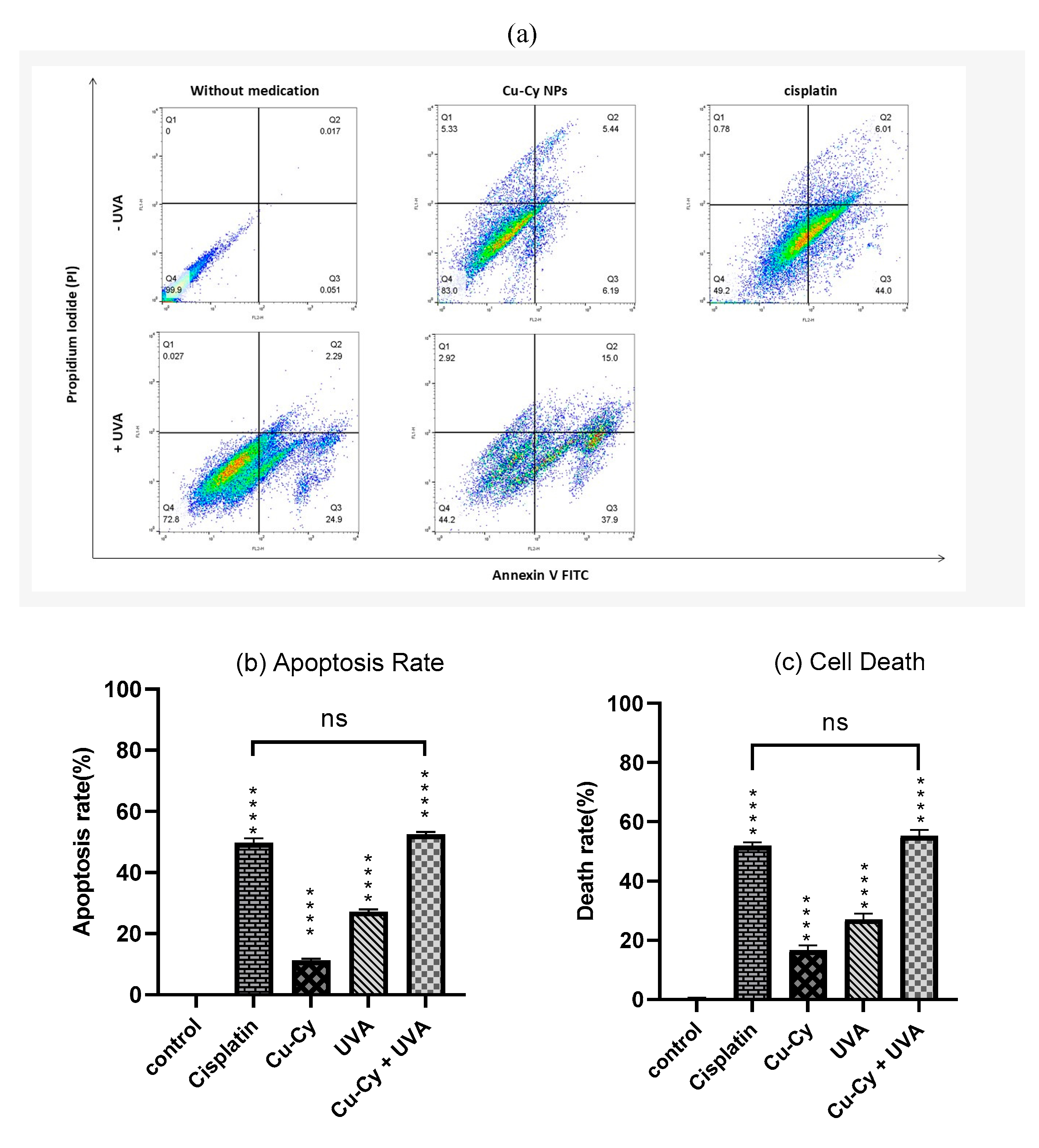

2.2.5. Apoptosis Assay Using Annexin V-FITC/PI Staining

Apoptotic cell death was assessed using an Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining kit (BioLegend, USA). 24 hours post-treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinization, collected by centrifugation, and washed twice with cold PBS. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 100 μL of 1× binding buffer, followed by the addition of 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC, and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 minutes. Then, 10 μL of PI solution was added to each sample. After incubation, 400 μL of binding buffer was added to each sample, and fluorescence was analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson, USA).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8. Data from at least three independent experiments are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). To assess statistical significance between two groups, an unpaired Student’s t-test was utilized. For comparisons involving three or more groups, either one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by a Tukey post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant

3. Result

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Cu-Cy NPs

The successful synthesis of Cu-Cy NPs was confirmed by their strong red luminescence under UV light irradiation at 365 nm (

Figure 2-a). UV-visible spectroscopy analysis showed an absorption peak around 365 nm when the Cu-Cy NPs were dispersed in deionized water (

Figure 2-b). Additionally, the photoluminescence emission spectra displayed a peak around 607 nm (illustrated by the red curve), while the excitation spectra indicated a peak approximately at 365 nm (represented by the Purple curve) (

Figure 2-c). Detailed information regarding the structure and properties of the Cu-Cy NPs has been reported in our previous paper [

22].

3.2. Synergistic Effect of Cu-Cy NPs and UVA Irradiation

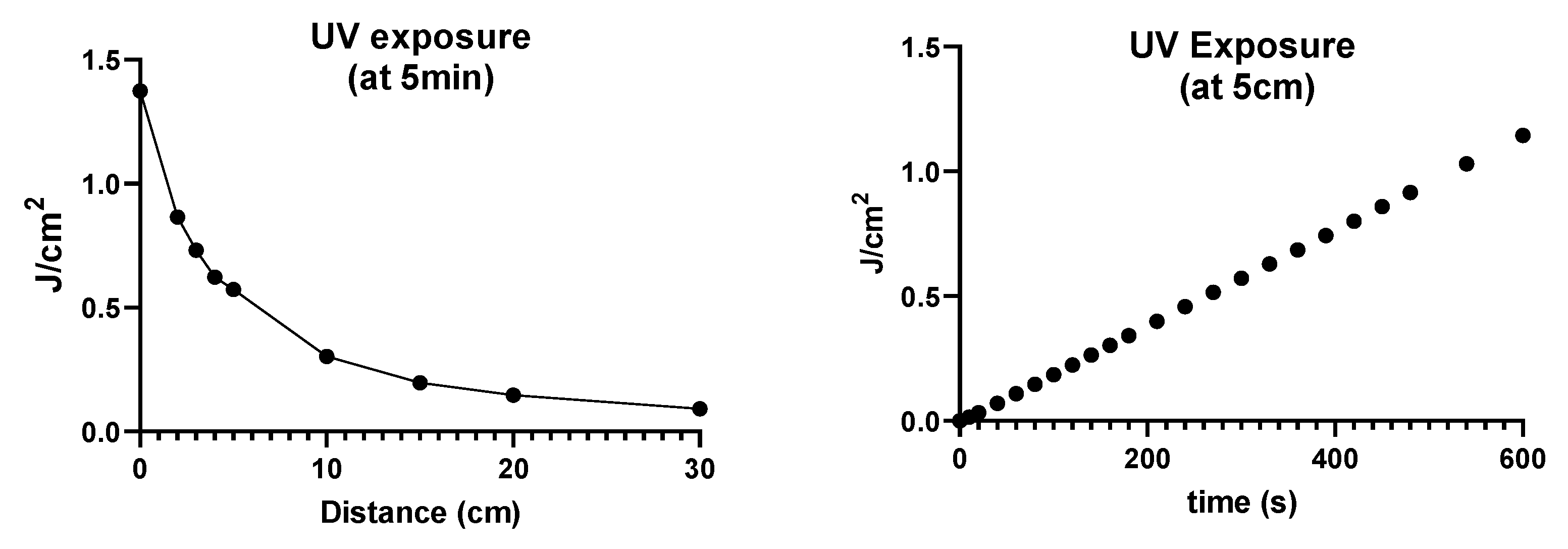

3.2.1. UVA Irradiation Dosimetry

As shown in

Figure 3, UVA dosimetry was performed under two different conditions to characterize the exposure setup. In the first assessment (

Figure 3, left ), irradiance was measured at various distances from the UVA lamp during a fixed 5-minute exposure. As expected, the delivered dose decreased with increasing distance from the source, highlighting the importance of maintaining a consistent lamp-to-sample distance to ensure reproducible irradiation conditions. In the second experiment (

Figure 3, right), the lamp was positioned at a fixed distance of 5 cm, matching the setup used for cell exposure, and the dose was recorded across increasing time intervals. A strong linear correlation between exposure time and energy delivered was observed, indicating that under stable lamp output, the cumulative UVA dose increases proportionally with irradiation time. According to the calibration curve, exposure durations of 2 and 10 minutes at 5 cm corresponded to approximately 0.24 J/cm² and 1.2 J/cm², respectively. These dose values were used as reference points in subsequent biological assays.

3.2.2. Cytotoxicity Assessment by MTT Assay

Cu-Cy NPs demonstrated a concentration-dependent reduction in cell viability, decreasing from 100% in untreated controls to 12.98% at 160 µg/mL. The calculated IC₅₀ value for Cu-Cy NPs was 21.82 μg/mL (

Figure 4a). In comparison, cisplatin exhibited significantly higher cytotoxic potency, with marked reductions in viability observed at concentrations above 20 μg/mL and an IC₅₀ of 11.87 μg/mL (

Figure 4b). To minimize confounding effects from nanoparticle-induced cytotoxicity, a subcytotoxic concentration of 3 μg/mL (equivalent to approximately 14% of the IC₅₀) was selected for subsequent combination assays. Preliminary UVA exposure–response experiments in A375 cells demonstrated a time-dependent decrease in cell viability. Based on these findings, two brief exposure durations of 2 minutes (low exposure) and 10 minutes (moderate exposure) were selected for subsequent ROS assays to evaluate potential synergy with Cu-Cy NPs while minimizing phototoxicity from UVA alone (

Figure 4c).

3.2.3. Intracellular ROS Generation Assessed by NBT Assay

Intracellular levels of ROS were evaluated 24 hours after treatment using the NBT assay. Significantly elevated ROS production was observed in cells treated with Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL) combined with 10 min UVA irradiation (relative ROS level: 2.125), and in the cisplatin group (11.87 μg/mL; relative ROS level: 2.69), relative to untreated controls (p < 0.0001). No significant differences in ROS levels were detected following UVA irradiation alone (2 min or 10 min), Cu-Cy NPs alone (3 μg/mL), or Cu-Cy NPs combined with 2 min UVA irradiation (p > 0.05). Notably, the cisplatin group induced higher ROS levels than the Cu-Cy NPs in combination with the 10-minute UVA group (p = 0.008). These findings highlight the importance of irradiation duration, with 10-minute exposure demonstrating a more pronounced ROS-inducing effect. Consequently, the Cu-Cy NPs + 10-minute UVA exposure was selected as the standard irradiation condition for further experiments (

Figure 5).

3.2.4. Apoptosis Analysis by Flow Cytometry

Apoptosis levels in A375 cells were evaluated by flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining. As shown in

Figure 6b and 6c, all treatment groups demonstrated significantly higher levels of apoptosis compared to the control group (p < 0.0001). The cisplatin-treated group showed 49.67±1.53% apoptosis, accompanied by 0.78% necrosis. Treatment with Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL) alone resulted in 11.21±0.82% apoptotic cells, while UVA irradiation for 10 minutes led to 27.23±0.75% apoptosis, with minimal necrosis (0.027%). The combination of Cu-Cy NPs and 10-minute UVA exposure resulted in 52.47±0.83% apoptosis with 2.92% necrosis. These values were significantly higher than those observed in the corresponding individual treatments, indicating a marked increase in apoptosis in the combination group.

Figure 6.

The apoptosis rate of A375 cells after treatment with Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL) and UVA (10 min), as well as their combination (Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL) + UVA (10 min)), was analyzed using a flow cytometry assay. Cisplatin (IC50) was utilized as a positive control in this analysis.

Figure 6.

The apoptosis rate of A375 cells after treatment with Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL) and UVA (10 min), as well as their combination (Cu-Cy NPs (3 μg/mL) + UVA (10 min)), was analyzed using a flow cytometry assay. Cisplatin (IC50) was utilized as a positive control in this analysis.

4. Discussion

PDT is a promising strategy to enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects in the treatment of melanoma. In PDT, a PS preferentially accumulates in malignant tissues and is activated by light at its specific absorption wavelength [

23]. This activation induces localized photo-oxidation, selectively damaging cancer cells while sparing surrounding healthy tissue [

24].

Cu-Cy NPs exhibit high single oxygen yield performance under UVA irradiation. ROS production by Cu-Cy is predominantly singlet oxygen, and the long luminescence decay lifetimes (7.399 μs and 0.363 ms) correspond to characteristic triplet-state transitions in effective photosensitizers. These observations confirm the presence of a stable triplet state in Cu-Cy NP, which is essential for efficient ROS generation [

25].

UV irradiation is well-known for its cytotoxic effects, primarily through absorption by nuclear DNA and the subsequent induction of ROS. This process leads to the formation of DNA photoproducts and inhibits DNA synthesis, ultimately activating the apoptosis cascade. UV also damages cytosolic and membrane targets within keratinocytes, reducing epidermal Langerhans cells and cutaneous T lymphocytes, and promoting the activation of regulatory T cells in lymph nodes. Key mechanisms underlying UV phototherapy include DNA damage, ROS generation, apoptosis induction, cytokine modulation, and immunosuppression [

26,

27]. These findings support the feasibility of using this approach as an alternative therapeutic strategy for melanoma, particularly considering the low penetration depth of UVA, which allows easy and cost-effective shielding of surrounding healthy tissues in potential

in vivo and

in vitro applications.

This study demonstrated a synergistic interaction between 10-minute UVA irradiation and Cu-Cy NPs, significantly increasing ROS production. Apoptosis assays also confirmed the synergistic effect of this combination. Notably, while the combination-induced ROS levels were lower than those generated by cisplatin, the resulting apoptosis rate did not differ statistically from that achieved by cisplatin. This suggests that mechanisms of cell death other than ROS-dependent pathways are likely contributing to the observed effect of the combination of UVA + Cu-Cy NP, and highlights the importance of exploring these additional mechanisms in future studies.

Our results are consistent with prior studies in HepG2 cells, indicating that ROS production increases with irradiation time and incites apoptosis by Cu-Cy NPs in combination with UVA [

14]. The different aspect was in melanoma cells, where they experienced similar effects in apoptosis induced at lower nanoparticle concentrations. This highlights the higher inherent sensitivity of melanoma cells, but it emphasizes the need to realize the major differences in response to treatment for specific cell lines.

Comparative analysis of UV sensitivity across cell lines further emphasizes variability in response to therapy. For instance, A375 cells were highly sensitive to UVA, exhibiting notable mortality even at low doses (1.2 J/cm² for 10 min), whereas HepG2 cells showed minor changes after higher doses (6 J/cm² for 5 min) [

14]. HaCaT cells required prolonged exposure (10 J/cm² for around 1 hour) to reach 50% cell death [

28], SK-MEL-37 cells showed minimal effects at 0.3 J/cm² [

29], and SK-MEL-30 and MCF-7 displayed intermediate apoptotic responses (1.5 J/cm², 50% and 20%, respectively) [

30]. These observations highlight the importance of considering cell-line-specific sensitivity in UV-based treatments.

Our data also reveal a non-linear relationship between UV exposure and cell mortality. At lower doses, cell death increased exponentially, but with prolonged exposure, mortality plateaued, resulting in a horizontal dose-response curve. This saturation effect suggests that beyond a certain threshold, additional energy delivered to the cells does not proportionally increase cell death, highlighting the complexity of UV-induced cytotoxic mechanisms.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Experiments were performed in vitro, and results may not fully translate to in vivo conditions where tissue penetration, tumor microenvironment, and immune responses play a role. Additionally, the range of UV doses and nanoparticle concentrations was limited, and only one melanoma cell line was primarily studied. Despite these challenges, the findings provide a solid foundation for future mechanistic and preclinical investigations.

5. Conclusion

The combination of Cu-Cy NPs and UVA irradiation effectively induces apoptosis in melanoma cells at relatively low nanoparticle concentrations, suggesting a promising alternative or adjunct to conventional chemotherapy. Future studies should explore in vivo efficacy, tissue penetration, and immune modulation to validate this approach further.

Author Contributions

M.R.N: The conception and design of the study, acquisition of data , Drafting the article, Final approval of the version; N.Ch.: Supervision , The conception and design of the study, Funding acquisition, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version; M.R.: Investigation, The conception and design of the study, Drafting the article; J.F.: Methodology, Drafting the article; M.N.S.: Investigation, Formal analysis; O.A.: Formal analysis, Drafting the article; Z.E.: acquisition of data; M.E.: The conception and design of the study, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version;.

Funding

This work was supported by the Office of Vice-Chancellor for Research of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences with grant number CMRC-0302.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.AJUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1403.005). The study was approved on April 29, 2024.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Dayer and Dr. Dehbashi for their constructive guidance during the experimental procedures, and Dr. Danyaei for providing access to essential facilities that supported this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- B. Ahmed, M.I. Qadir, S. Ghafoor, Malignant Melanoma: Skin Cancer-Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment, Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 30 (2020) 291–297. [CrossRef]

- M.F. Jojoa Acosta, L.Y. Caballero Tovar, M.B. Garcia-Zapirain, W.S. Percybrooks, Melanoma diagnosis using deep learning techniques on dermatoscopic images, BMC Med. Imaging 21 (2021) 6. [CrossRef]

- Y.-Y. Lin, C.-Y. Chen, D.-L. Ma, C.-H. Leung, C.-Y. Chang, H.-M.D. Wang, Cell-derived artificial nanovesicle as a drug delivery system for malignant melanoma treatment, Biomed. Pharmacother. 147 (2022) 112586. [CrossRef]

- L. Zeng, B.H.J. Gowda, M.G. Ahmed, M.A.S. Abourehab, Z.-S. Chen, C. Zhang, J. Li, P. Kesharwani, Advancements in nanoparticle-based treatment approaches for skin cancer therapy, Mol. Cancer 22 (2023) 10. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Hamblin, Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer: What’s Past is Prologue, Photochem. Photobiol. 96 (2020) 506–516. [CrossRef]

- C.-N. Lee, R. Hsu, H. Chen, T.-W. Wong, Daylight Photodynamic Therapy: An Update., Molecules 25 (2020). [CrossRef]

- B. Halliwell, Free radicals and antioxidants - quo vadis?, Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 32 (2011) 125–130. [CrossRef]

- G.M.F. Calixto, J. Bernegossi, L.M. de Freitas, C.R. Fontana, M. Chorilli, Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: A Review., Molecules 21 (2016) 342. [CrossRef]

- I. Yoon, J.Z. Li, Y.K. Shim, Advance in photosensitizers and light delivery for photodynamic therapy., Clin. Endosc. 46 (2013) 7–23. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Wilson, Photodynamic therapy for cancer: principles., Can. J. Gastroenterol. 16 (2002) 393–396. [CrossRef]

- K. Kalka, H. Merk, H. Mukhtar, Photodynamic therapy in dermatology, J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 42 (2000) 389–413. [CrossRef]

- H. Abrahamse, M.R. Hamblin, New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy, Biochem. J. 473 (2016) 347–364. [CrossRef]

- J.C.S. Simões, S. Sarpaki, P. Papadimitroulas, B. Therrien, G. Loudos, Conjugated Photosensitizers for Imaging and PDT in Cancer Research, J. Med. Chem. 63 (2020) 14119–14150. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, F. Wan, L. Ma, J.B. Phan, R.X. Lim, C. Li, J. Chen, J. Deng, Y. Li, W. Chen, M. He, Investigation of copper-cysteamine nanoparticles as a new photosensitizer for anti-hepatocellular carcinoma, Cancer Biol. Ther. 20 (2019) 812–825. [CrossRef]

- S. Shrestha, J. Wu, B. Sah, A. Vanasse, L.N. Cooper, L. Ma, G. Li, H. Zheng, W. Chen, M.P. Antosh, X-ray induced photodynamic therapy with copper-cysteamine nanoparticles in mice tumors, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116 (2019) 16823–16828. [CrossRef]

- M. Yao, L. Ma, L. Li, J. Zhang, R.X. Lim, W. Chen, Y. Zhang, A New Modality for Cancer Treatment—Nanoparticle Mediated Microwave Induced Photodynamic Therapy, J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 12 (2016) 1835–1851. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, X. Wang, L. Ma, S. Sahi, L. Li, X. Wang, Q. Wang, Y. Chen, W. Chen, Q. Liu, Nanosonosensitization by Using Copper–Cysteamine Nanoparticles Augmented Sonodynamic Cancer Treatment, Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 35 (2018) 1700378. [CrossRef]

- L. Chudal, N.K. Pandey, J. Phan, O. Johnson, L. Lin, H. Yu, Y. Shu, Z. Huang, M. Xing, J.P. Liu, M.-L. Chen, W. Chen, Copper-Cysteamine Nanoparticles as a Heterogeneous Fenton-Like Catalyst for Highly Selective Cancer Treatment, ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3 (2020) 1804–1814. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, X. Guo, Y. Cheng, L. Chudal, N.K. Pandey, J. Zhang, L. Ma, Q. Xi, G. Yang, Y. Chen, X. Ran, C. Wang, J. Zhao, Y. Li, L. Liu, Z. Yao, W. Chen, Y. Ran, R. Zhang, Use of copper-cysteamine nanoparticles to simultaneously enable radiotherapy, oxidative therapy and immunotherapy for melanoma treatment, Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5 (2020) 58. [CrossRef]

- N.R. York, H.T. Jacobe, UVA1 phototherapy: a review of mechanism and therapeutic application., Int. J. Dermatol. 49 (2010) 623–630. [CrossRef]

- N.K. Pandey, L. Chudal, J. Phan, L. Lin, O. Johnson, M. Xing, J.P. Liu, H. Li, X. Huang, Y. Shu, W. Chen, A facile method for the synthesis of copper–cysteamine nanoparticles and study of ROS production for cancer treatment, J. Mater. Chem. B 7 (2019) 6630–6642. [CrossRef]

- M. Ejtema, N. Chegeni, A. Zarei-Ahmady, Z. Salehnia, M. Shamsi, S. Razmjoo, Exploring the combined impact of cisplatin and copper-cysteamine nanoparticles through Chemoradiation: An in-vitro study, Toxicol. Vitr. 99 (2024) 105878. [CrossRef]

- M. Kolarikova, B. Hosikova, H. Dilenko, K. Barton-Tomankova, L. Valkova, R. Bajgar, L. Malina, H. Kolarova, Photodynamic therapy: Innovative approaches for antibacterial and anticancer treatments., Med. Res. Rev. 43 (2023) 717–774. [CrossRef]

- B.W. Henderson, T.J. Dougherty, How does photodynamic therapy work?, Photochem. Photobiol. 55 (1992) 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, L. Xiong, G. Ouyang, L. Ma, S. Sahi, K. Wang, L. Lin, H. Huang, X. Miao, W. Chen, Y. Wen, Investigation of Copper Cysteamine Nanoparticles as a New Type of Radiosensitiers for Colorectal Carcinoma Treatment, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 9290. [CrossRef]

- T.L. de Jager, A.E. Cockrell, S.S. Du Plessis, Ultraviolet Light Induced Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species, in: Ultrav. Light Hum. Heal. Dis. Environ., Springer, 2017: pp. 15–23. [CrossRef]

- C.-H. Lee, S.-B. Wu, C.-H. Hong, H.-S. Yu, Y.-H. Wei, Molecular Mechanisms of UV-Induced Apoptosis and Its Effects on Skin Residential Cells: The Implication in UV-Based Phototherapy, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (2013) 6414–6435. [CrossRef]

- Z. He, L. Zhang, C. Zhuo, F. Jin, Y. Wang, Apoptosis inhibition effect of Dihydromyricetin against UVA-exposed human keratinocyte cell line, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 161 (2016) 40–49. [CrossRef]

- V. Carneiro Leite, R. Ferreira Santos, L. Chen Chen, L. Andreu Guillo, Psoralen derivatives and longwave ultraviolet irradiation are active in vitro against human melanoma cell line, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 76 (2004) 49–53. [CrossRef]

- M.T. Bilkan, Z. Çiçek, A.G.C. Kurşun, M. Özler, M.A. Eşmekaya, Investigations on effects of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticle in combination with UV radiation on breast and skin cancer cells, Med. Oncol. 40 (2022) 60. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).