Single-cell biology has fundamentally transformed our understanding of plant systems. Over the past decade, advancements in transcriptomics at the cellular level have unveiled that what once appeared as uniform tissues are, in fact, intricate mosaics of diverse and dynamic cell types. This groundbreaking perspective has catalyzed a revolution in plant biology, illuminating developmental trajectories, stress responses, and lineage hierarchies that remained obscured by traditional bulk analysis methods. By peeling back the layers of cellular complexity, we are now equipped to explore the rich diversity of cellular behavior and organization within plants, ultimately challenging long-held assumptions and opening new avenues for research and application in plant science (Rusnak et al., 2024). Despite the rapid advancements in single-cell genomics, epigenomics, and transcriptomics, single-cell metabolomics is gradually emerging as a formidable contender in this evolving landscape, challenging the dominance of its counterparts in profound and intriguing ways.

Plant metabolites, the vital molecules that directly influence biological function, are not just passive players; they orchestrate energy distribution, shape interactions between plants and their environments, and are pivotal in determining crucial traits such as crop yield and medicinal efficacy (Shen et al., 2023). Understanding the spatial and cell-type distribution of metabolites is essential for advancing our knowledge in the field. Yet, it is paradoxical that single-cell metabolomics relies heavily on transcriptomics to establish cell identity, a fundamental task. This reliance not only hampers accessibility and raises costs but also undermines the conceptual independence needed for innovation (Pandian et al., 2023). The time has arrived to redefine our approach to plant cell identity through the innovative concept of cell-type-specific chemical fingerprints. These chemical fingerprints, consisting of reproducible sets of metabolites that are uniquely enriched in specific plant cell types, promise to serve as vital identity markers, complementing or even surpassing transcriptomic data. While these metabolic signatures may begin as phylogenetic clade-specific or lineage-restricted, their expansion and comparison across various plant groups could establish a stable and accessible framework for defining cell identities. By harnessing this concept, we not only deepen our understanding of plant biology but also lay the groundwork for transformative advancements in agricultural biotechnology and ecological conservation, pushing the boundaries of what we can achieve in plant science.

Why Are Transcriptomes Not Enough?

Transcriptomics has long been the go-to method for classifying plant cell types, yet its shortcomings are becoming increasingly clear. The plasticity of plant transcriptomes is remarkable; they can change rapidly in response to developmental stages, circadian rhythms, and environmental stressors. For instance, a root cortical cell can dramatically alter its gene expression within mere hours of drought stress, highlighting the dynamic nature of plant responses. Furthermore, homologous tissues across different lineages may utilize entirely distinct regulatory mechanisms, challenging the assumptions of a uniform classification based on transcriptomic data (Rusnak et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2025) This variability complicates the notion of a “canonical” transcriptome for any given cell type. Transcriptomics presents considerable challenges, as it is both costly and reliant on extensive infrastructure. The high-throughput single-cell sequencing demands specialized platforms, intricate computational pipelines, and robust data management systems. This high barrier to entry often excludes many laboratories, especially those in biodiversity-rich yet resource-limited areas of the Global South, effectively sidelining them from the transformative single-cell revolution (Wen et al., 2022). Finally, metabolomics remains tethered to transcriptomics for identity assignments. If this dependence continues, single-cell metabolomics risks remaining a satellite field, defined and constrained by the most resource-intensive omics layer.

Chemistry as Identity

Plants already provide strong evidence that chemistry encodes identity. Photosynthetic pigments such as chlorophylls are strictly localized to mesophyll and guard cells, while flavonoid glycosides are enriched in epidermal cells, where they confer UV protection (Misra et al., 2014). Xylem cells are distinguished by their deposition of lignins and lignan precursors, and Organic acids such as malate and citrate not only contribute to metabolic flux but also buffer pH across developmental tissues, with their levels adjusting predictably in line with spatial and physiological gradients (Igamberdiev and Bykova, 2018; Liu, 2012) Meanwhile, lipid derivatives such as cuticular waxes—synthesized by epidermal cells from very-long chain fatty acids—and suberin—strategically deposited in the endodermis—forcibly impose hydrophobic boundaries that not only demarcate cell-layer identity but also provoke a reconsideration of how structure governs biological function (Philippe et al., 2022). Even without sophisticated tools, autofluorescence microscopy reveals distinct intrinsic patterns: chlorophyll glows red, lignin blue, phenolics green. These examples demonstrate that plants already encode aspects of cell identity chemically. The challenge is to move from anecdotal observations to a formalized chemical fingerprint framework, consisting of consistent sets of metabolites that define major plant cell classes across contexts and species.

Beyond the “Universal”: Clade-Specific Opportunities

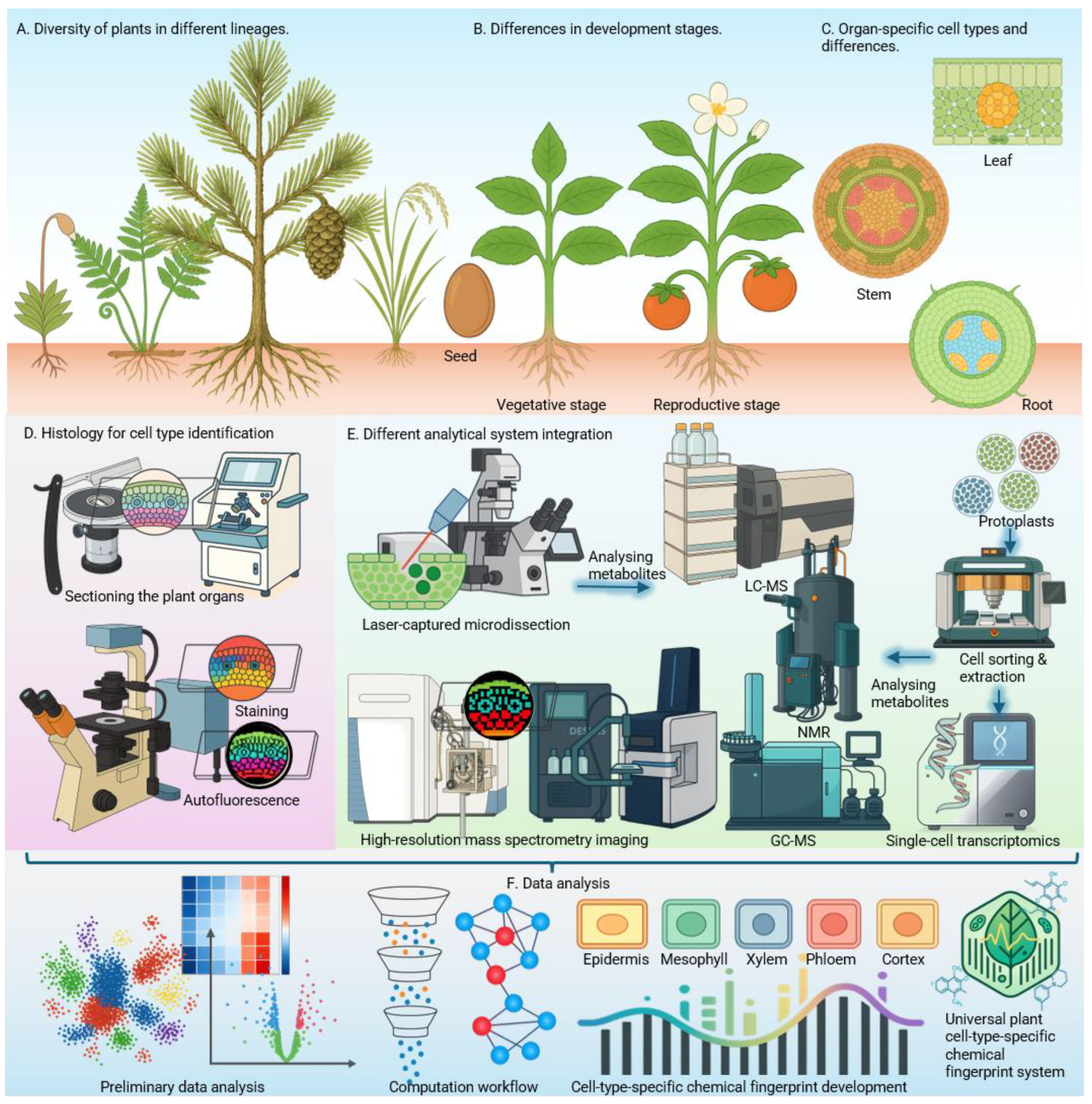

A universal barcode spanning all of plant phylogeny is an ambitious long-term goal. But progress does not require universality from the outset. Even lineage- or clade-specific barcodes would represent transformative tools (

Figure 1A). Bryophyte-specific signatures could illuminate how the earliest land plants partitioned metabolism at the cellular level. Monocot-specific markers would directly aid cereal research, where single-cell omics is rapidly advancing. For angiosperms, major flowering plant orders such as Poales, Fabales, or Solanales could be prioritized for crop-focused applications. Such partial frameworks would guide evolutionary comparisons while also delivering immediate translational value for crop improvement, stress biology, and synthetic biology (Daloso et al., 2023; Nobori, 2025). Over time, integrating clade-specific panels may reveal deeper conserved signatures, the hidden universality within what we call “cell-type specific” chemical fingerprints.

From Data to Knowledge: Computational Integration

Defining chemical fingerprints will not emerge automatically from instrumentation; it requires computational synthesis. Bioinformatics pipelines must integrate MSI maps, LCM datasets, autofluorescence cues, and curated metabolomics data into coherent cell-type atlases (

Figure 1F) (Birnbaum

et al., 2022). Machine learning models are well suited to detect recurrent patterns that correlate with identity across species and contexts (Shen

et al., 2023). Emerging tools such as chemical tagging MS and large language models could further accelerate discovery by mining scattered literature for references to cell-specific metabolites and connecting them into candidate chemical fingerprint panels (Lu

et al., 2023). As Nobori (2025) recently argued, integrating spatial omics with metabolomics is crucial for unlocking plant single-cell biology at scale. This convergence of instrumentation and computation makes the discovery of chemical fingerprints both timely and feasible.

Why Now?

Three converging trends make this the moment to pursue chemical fingerprints. First, technical readiness: high-resolution MSI and single-cell sampling methods now allow detection of hundreds of metabolites at micrometer resolution(Boughton et al., 2016; Yamamoto et al., 2016). Second, computational maturity: algorithms for multimodal integration, trajectory inference, and AI-driven annotation are already being applied in mammalian and clinical contexts, and are ready to extend to plants (Wen et al., 2022). Third, equity: by reducing reliance on transcriptomics, chemical fingerprints could democratize single-cell research. For biodiversity-rich regions with limited sequencing infrastructure, this shift would open new opportunities for discovery and participation in global plant science (Passi et al., 2025). Without such a shift, plant single-cell metabolomics risks remaining permanently dependent on transcriptomics. With it, the field can establish its own identity: independent, accessible, and future-facing.

A Call to Collaboration

Achieving this vision requires broad collaboration across the plant sciences. Classical botanists and plant physiologists bring essential knowledge of cell anatomy, structure, and function. MSI specialists and analytical chemists provide technical expertise in spatial detection (Boughton

et al., 2016). Natural product chemists contribute decades of insight into metabolite diversity and structural elucidation. Single-cell experts in genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics offer critical perspectives on data generation, annotation, and integration (Yu

et al., 2023). Finally, bioinformaticians and computational scientists contribute the pipelines, machine learning frameworks, and AI-driven models needed to translate raw data into reproducible chemical fingerprints (Birnbaum

et al., 2022). Only by uniting these communities can we establish robust, cell-type specific chemical fingerprints for plants (

Figure 1).

Looking Forward: A Chemical Grammar of Plant Cells

Imagine a future where plant cell identity is not inferred from thousands of transcripts but read directly from a handful of stable metabolites: mesophyll cells identified by chlorophyll and flavonoids, xylem cells by lignin precursors, epidermal cells by flavonoids and cuticular lipids. Each cell type is defined by its own chemical fingerprint, reproducible, stable, and accessible. Such a system would not replace transcriptomics but complement and liberate it. Transcriptomes will remain essential for exploring regulatory nuance, but metabolic barcodes would provide the anchor, the grammar to assemble these insights into a shared language of plant cell identity. The time is right, the tools are here, and the need is urgent. If transcriptomes have given us the dictionary of plant cell types, chemical fingerprint could become the grammar — simple, universal in principle, and accessible to all.

Author contributions

Conceptualization – Methodology– Visualization– Writing – original draft– review & editing: NSL

Data and materials availability

All data are available in the main text.

Acknowledgments

The author used ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI) to assist with text editing and to generate some elements for the figure. All content was subsequently reviewed by the author, who assumes full responsibility for the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Birnbaum, K.D.; Otegui, M.S.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Rhee, S.Y. The Plant Cell Atlas: focusing new technologies on the kingdom that nourishes the planet. Plant Physiol. 2021, 188, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughton, B.A.; Thinagaran, D.; Sarabia, D.; Bacic, A.; Roessner, U. Mass spectrometry imaging for plant biology: a review. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 15, 445–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daloso DdM, Morais EG, Oliveira e Silva KF, Williams TCR. 2023. Cell-type-specific metabolism in plants. The Plant Journal 114, 1093–1114.

- Igamberdiev, A.U.; Bykova, N.V. Role of organic acids in the integration of cellular redox metabolism and mediation of redox signalling in photosynthetic tissues of higher plants. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-J. Deciphering the Enigma of Lignification: Precursor Transport, Oxidation, and the Topochemistry of Lignin Assembly. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, L. Chemical tagging mass spectrometry: an approach for single-cell omics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 6901–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, B.B.; Assmann, S.M.; Chen, S. Plant single-cell and single-cell-type metabolomics. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobori, T. Exploring the untapped potential of single-cell and spatial omics in plant biology. New Phytol. 2025, 247, 1098–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, K.; Matsui, M.; Hankemeier, T.; Ali, A.; Okubo-Kurihara, E. Advances in single-cell metabolomics to unravel cellular heterogeneity in plant biology. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passi, A.; Tec-Campos, D.; Kumar, M.; Tibocha-Bonilla, J.D.; Zuñiga, C.; Peacock, B.; Hale, A.; Santibáñez-Palominos, R.; Borneman, J.; Zengler, K. Unveiling organ-specific metabolism of Citrus clementina. . 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippe, G.; De Bellis, D.; Rose, J.K.C.; Nawrath, C. Trafficking Processes and Secretion Pathways Underlying the Formation of Plant Cuticles. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 786874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusnak, B.; Clark, F.K.; Vadde, B.V.L.; Roeder, A.H. What Is a Plant Cell Type in the Age of Single-Cell Biology? It's Complicated. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 40, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Zhan, C.; Yang, C.; Fernie, A.R.; Luo, J. Metabolomics-centered mining of plant metabolic diversity and function: Past decade and future perspectives. Mol. Plant 2022, 16, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Li, G.; Huang, T.; Geng, W.; Pei, H.; Yang, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, P.; Hou, R.; Tian, G.; et al. Single-cell technologies: From research to application. Innov. 2022, 3, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Takahashi, K.; Mizuno, H.; Anegawa, A.; Ishizaki, K.; Fukaki, H.; Ohnishi, M.; Yamazaki, M.; Masujima, T.; Mimura, T. Cell-specific localization of alkaloids in Catharanthus roseus stem tissue measured with Imaging MS and Single-cell MS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 3891–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Cao, S.; Li, W.; Yang, G.; He, C. Progress in Transcriptomics and Metabolomics in Plant Responses to Abiotic Stresses. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X. Single-cell and spatial multi-omics in the plant sciences: Technical advances, applications, and perspectives. Plant Commun. 2022, 4, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).