Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

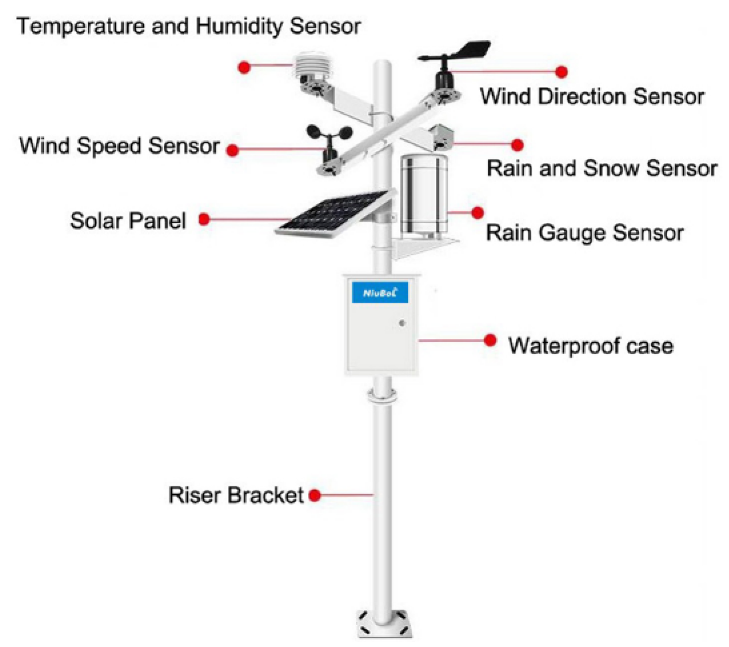

2.1. Weather Station

2.2. Anomalies In Weather Observation Data

2.3. Weather Forecasting Systems Based on Machine Learning

3. Study Area And Weather Data

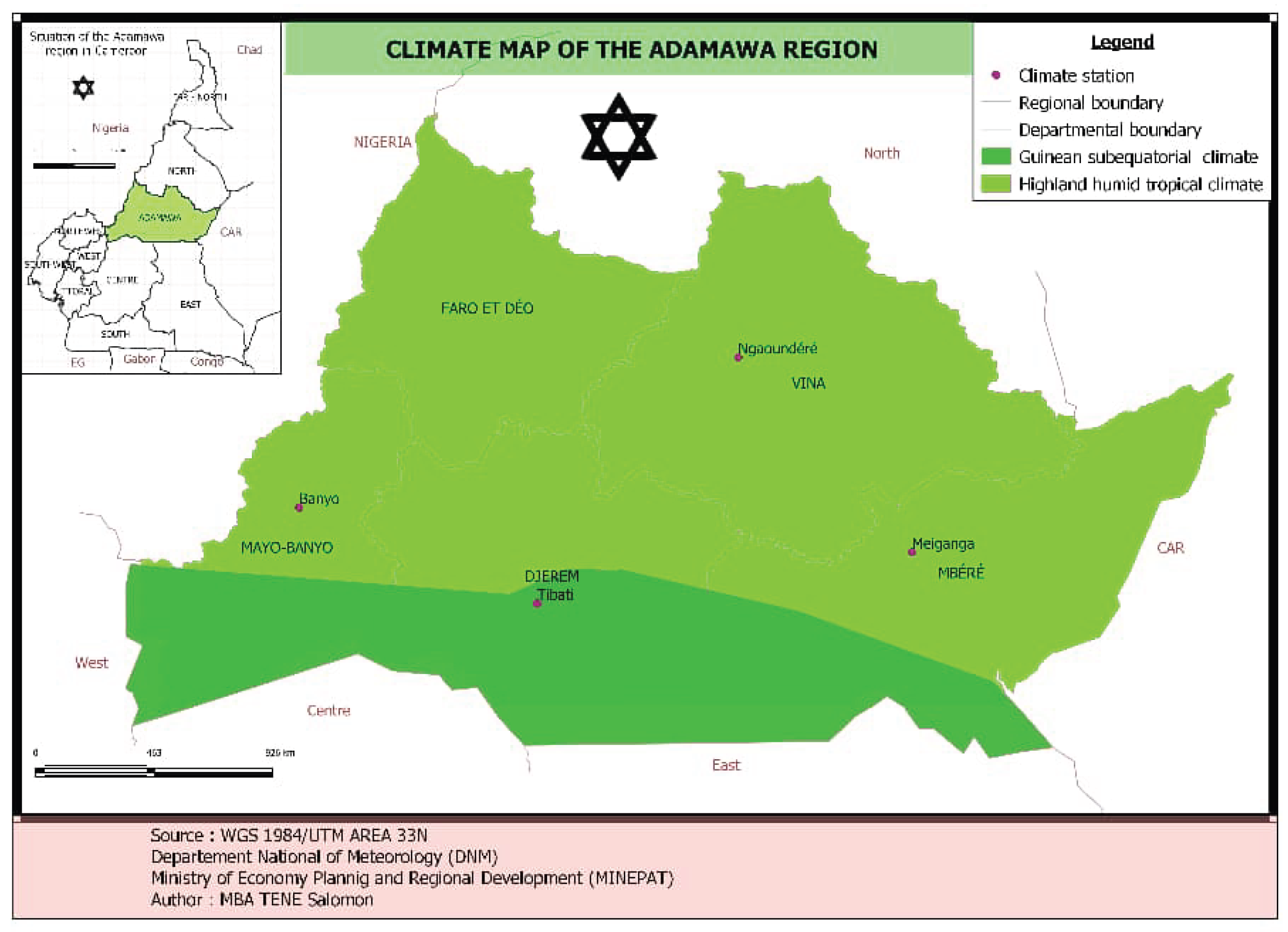

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Weather Data

| Weather Parameters | Symbols | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | T2M | Celsius |

| Relative humidity | R2HM | Percentage |

| Precipitation | PRECTOTCORR | millimetre |

| Dew point | T2MDEW | Farenheit |

| Air pressure | PS | Hectopascals |

4. Methods And Tools

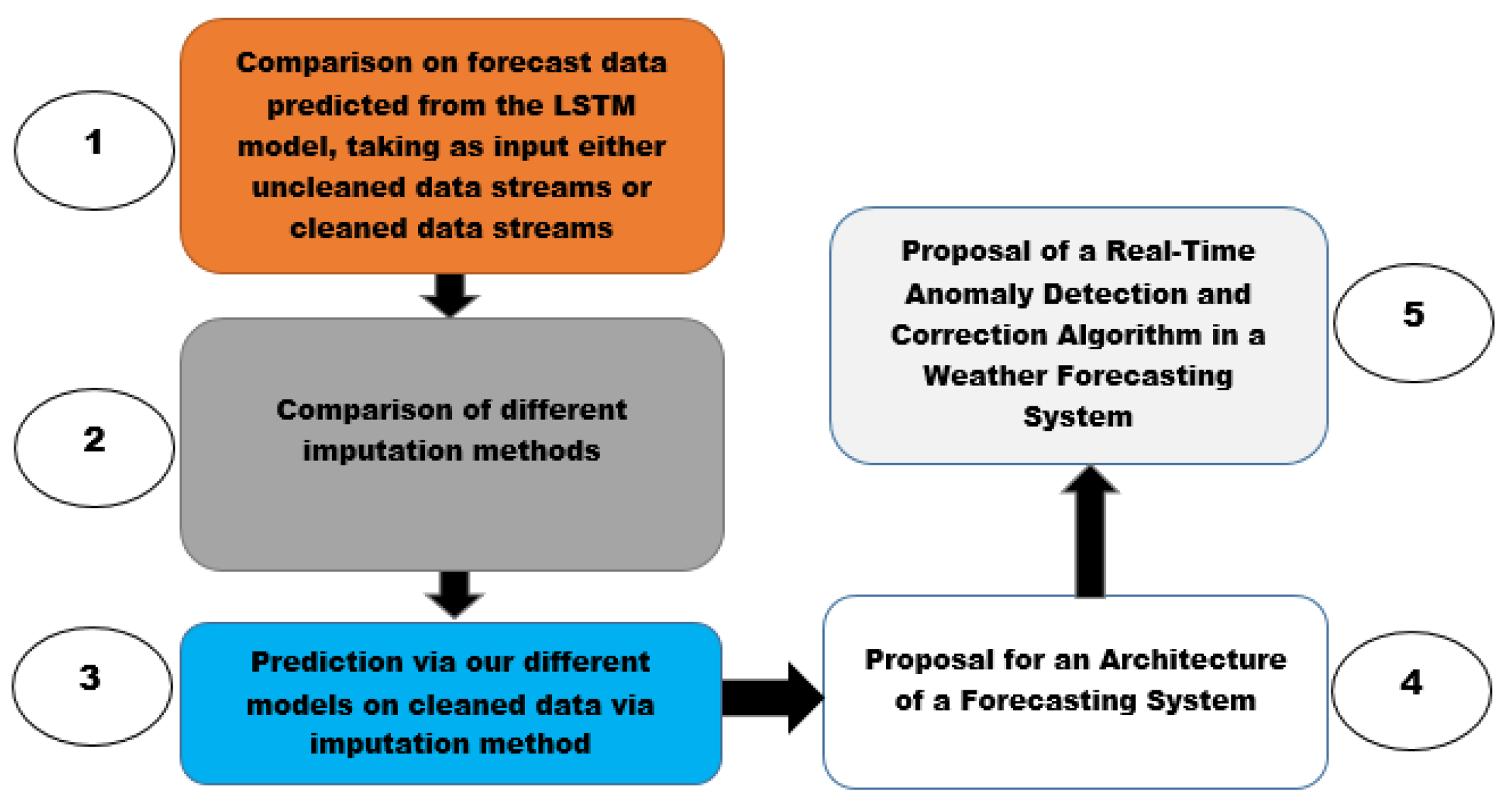

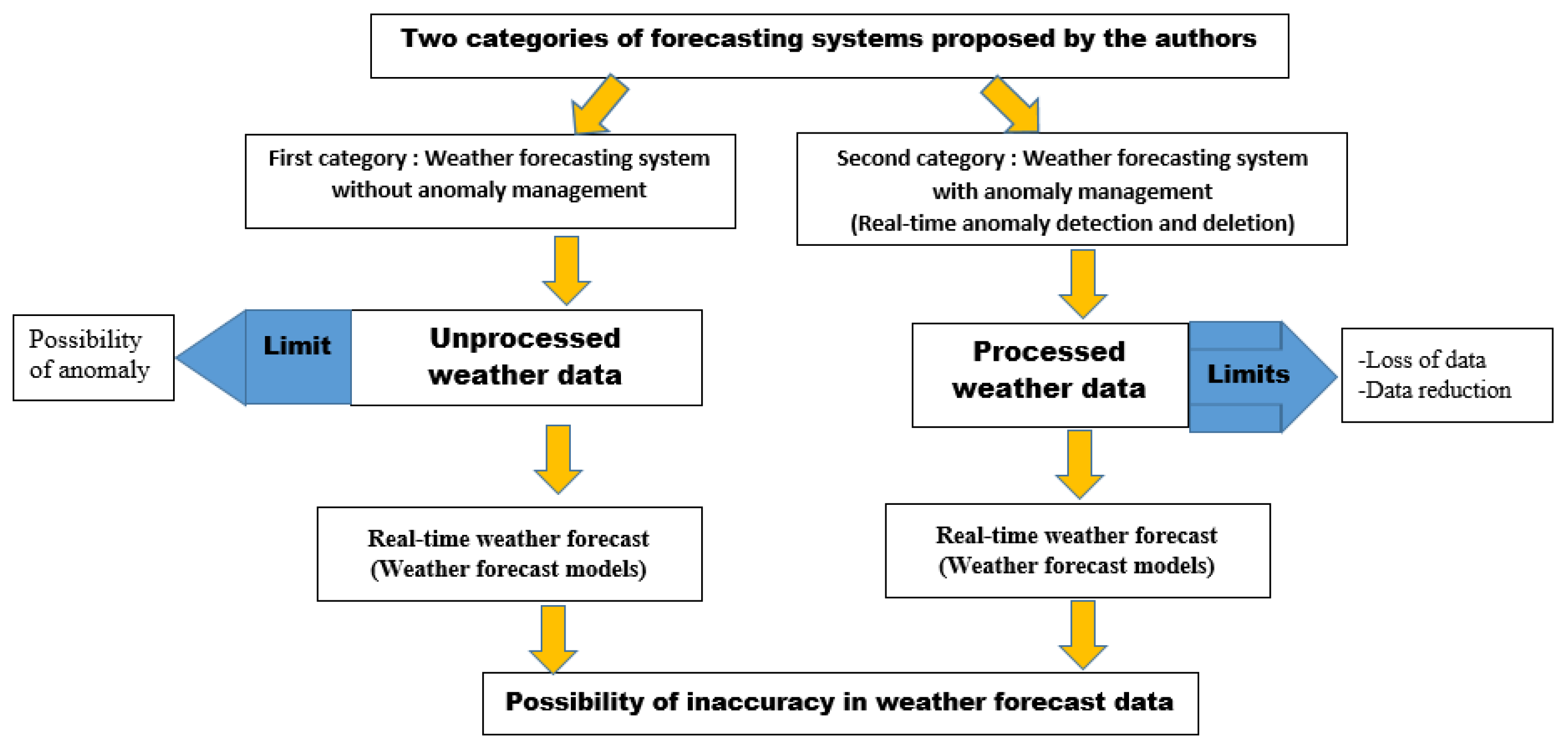

4.1. Methodological Framework

- -

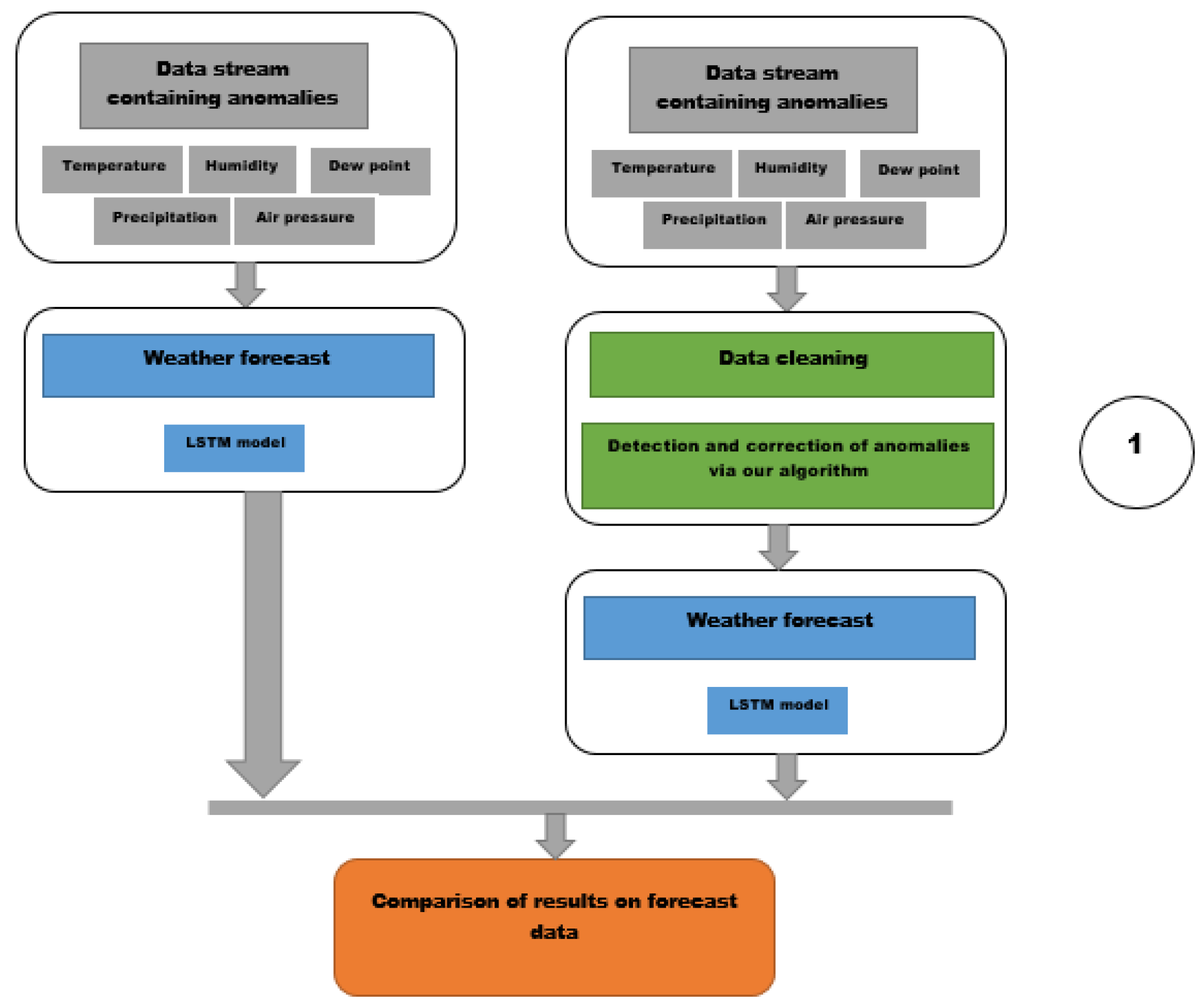

- Step 1 : Comparison of the forecast data predicted by the LSTM model, using the uncleaned data stream as input on one hand and the cleaned data stream on the other hand. This step shows how the forecasting model becomes inaccurate when the data stream contains anomalies. Figure 5 describes step 1;

- -

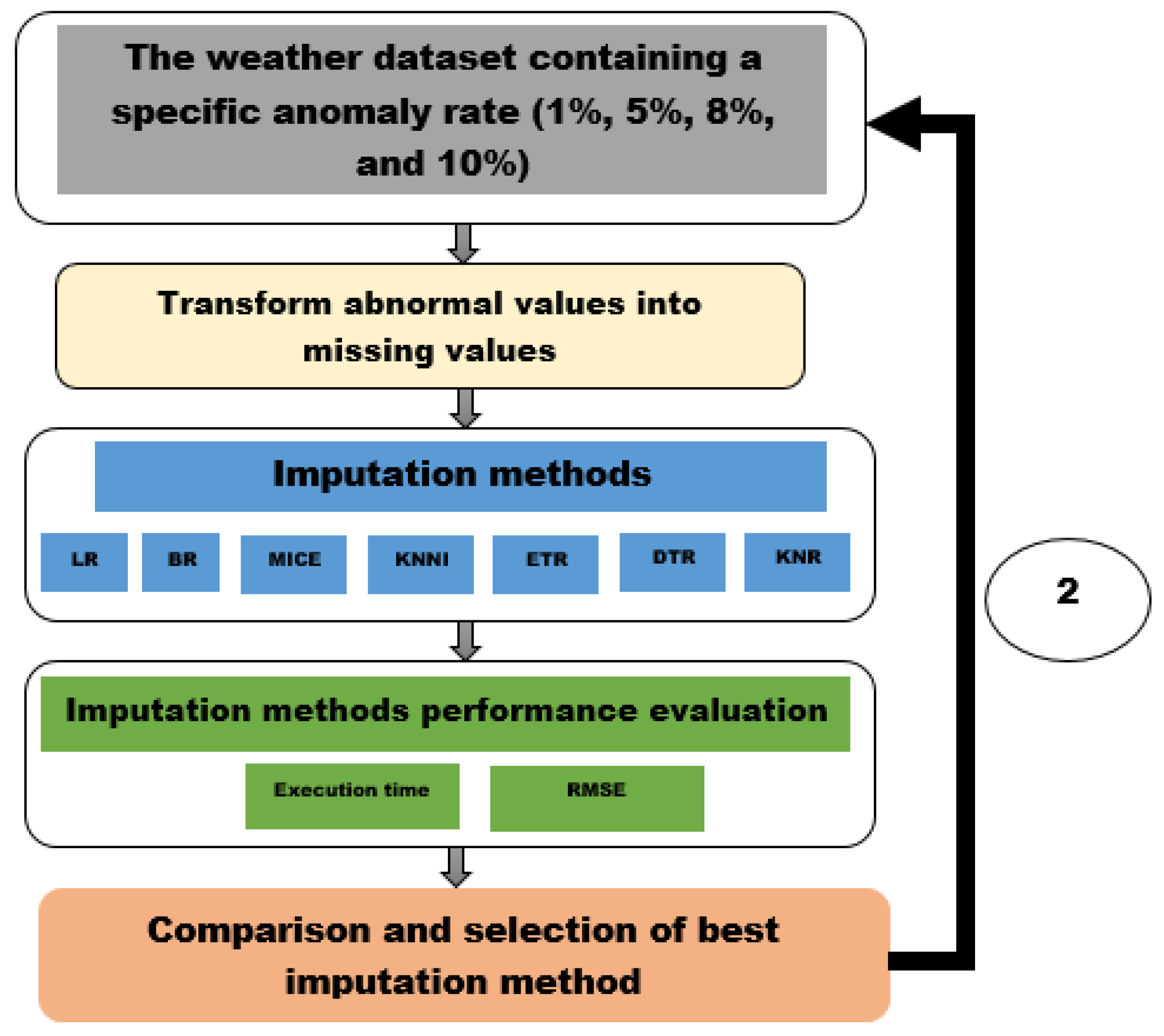

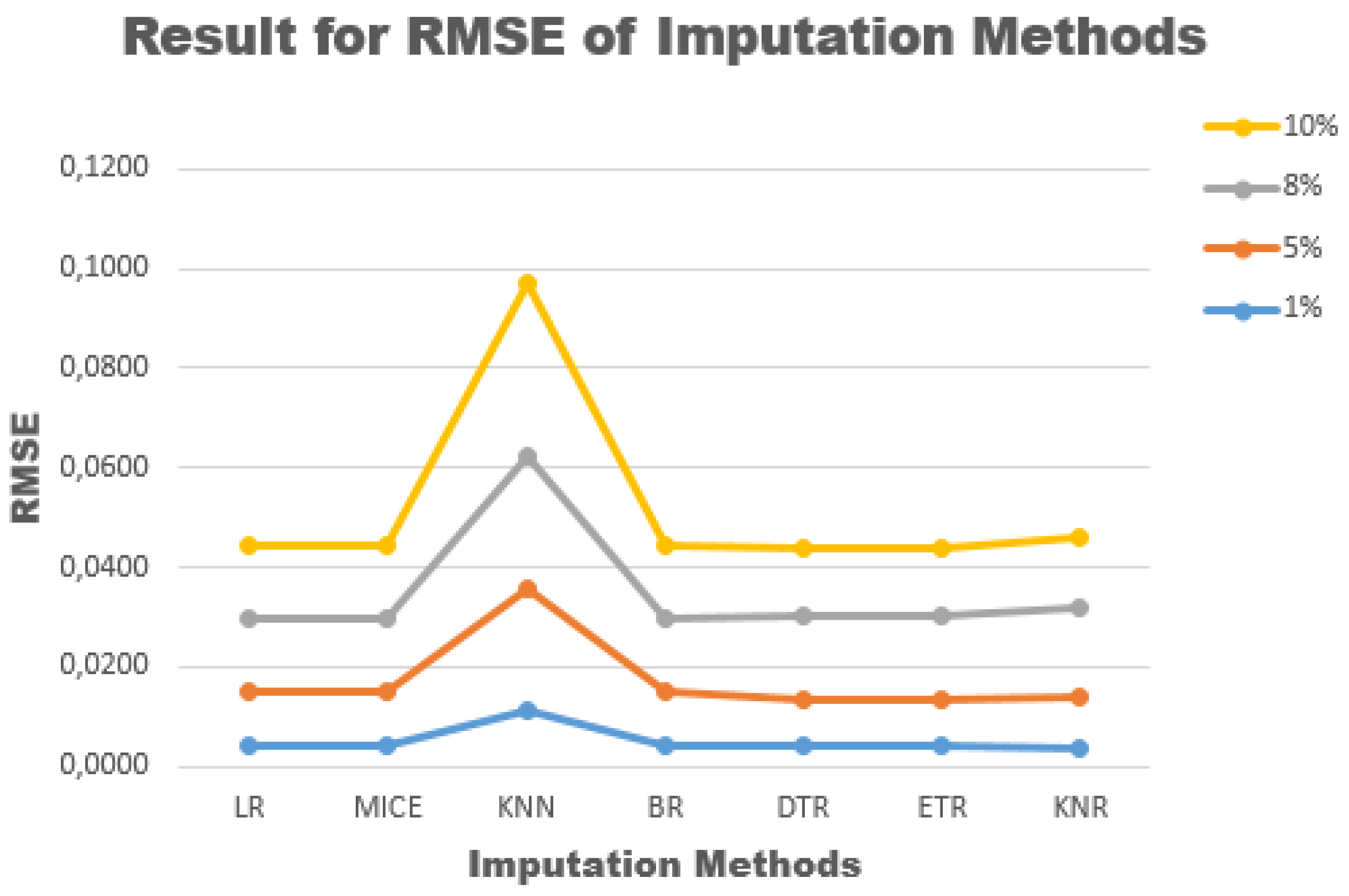

- Step 2 : Comparison of different allocation methods. Performance evaluation metrics are based on accuracy and execution time. Figure 6 illustrates the process of comparing different imputation methods;

- -

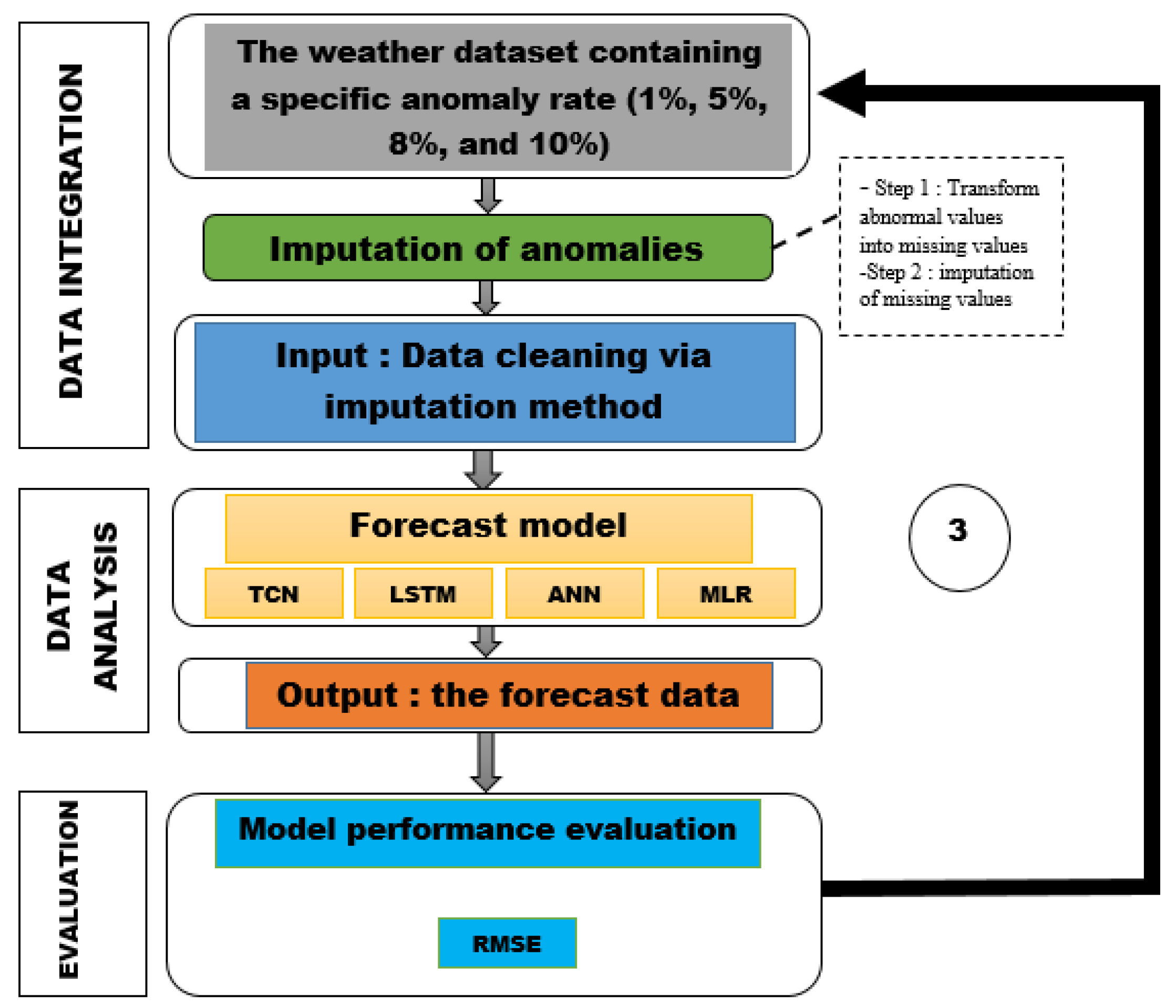

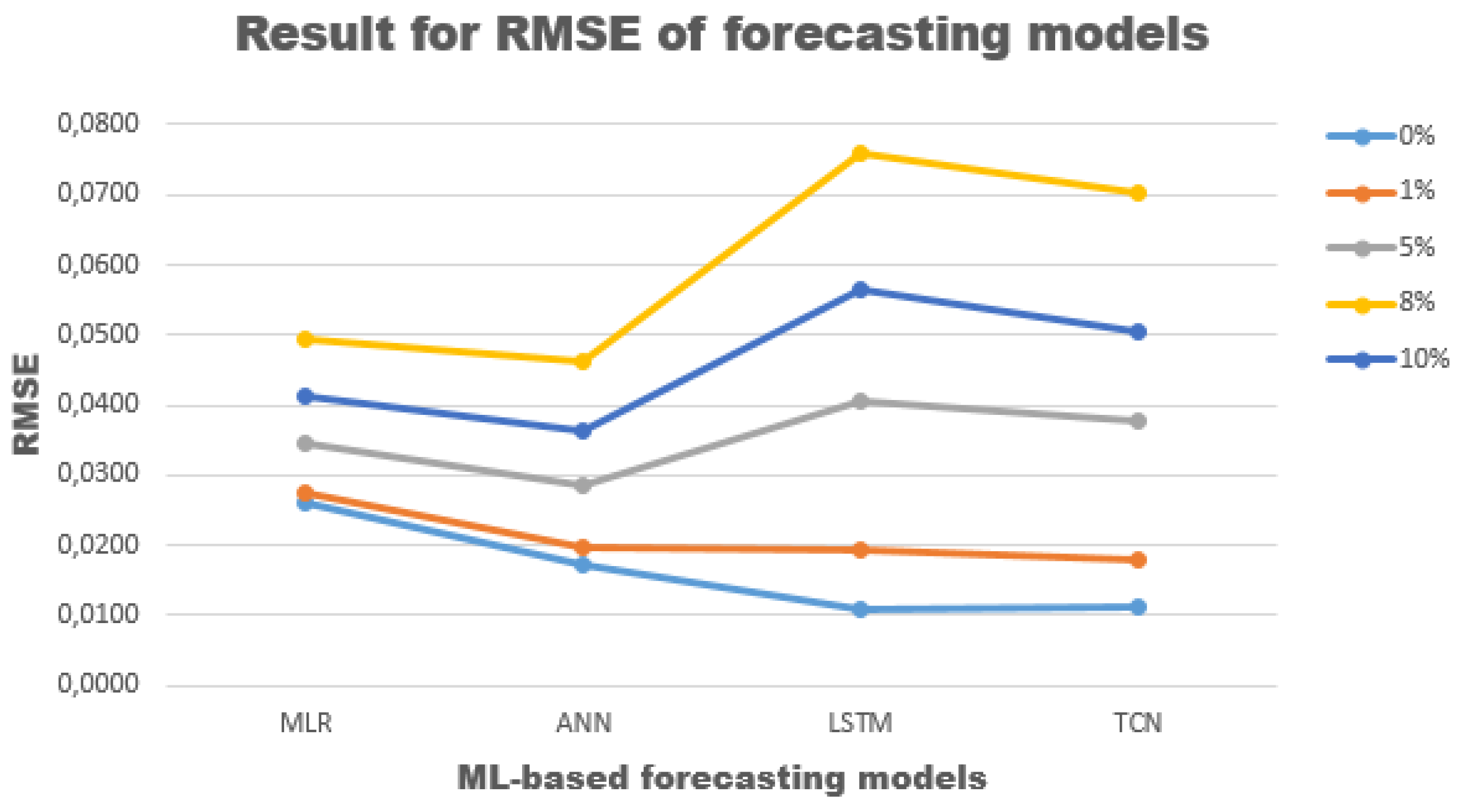

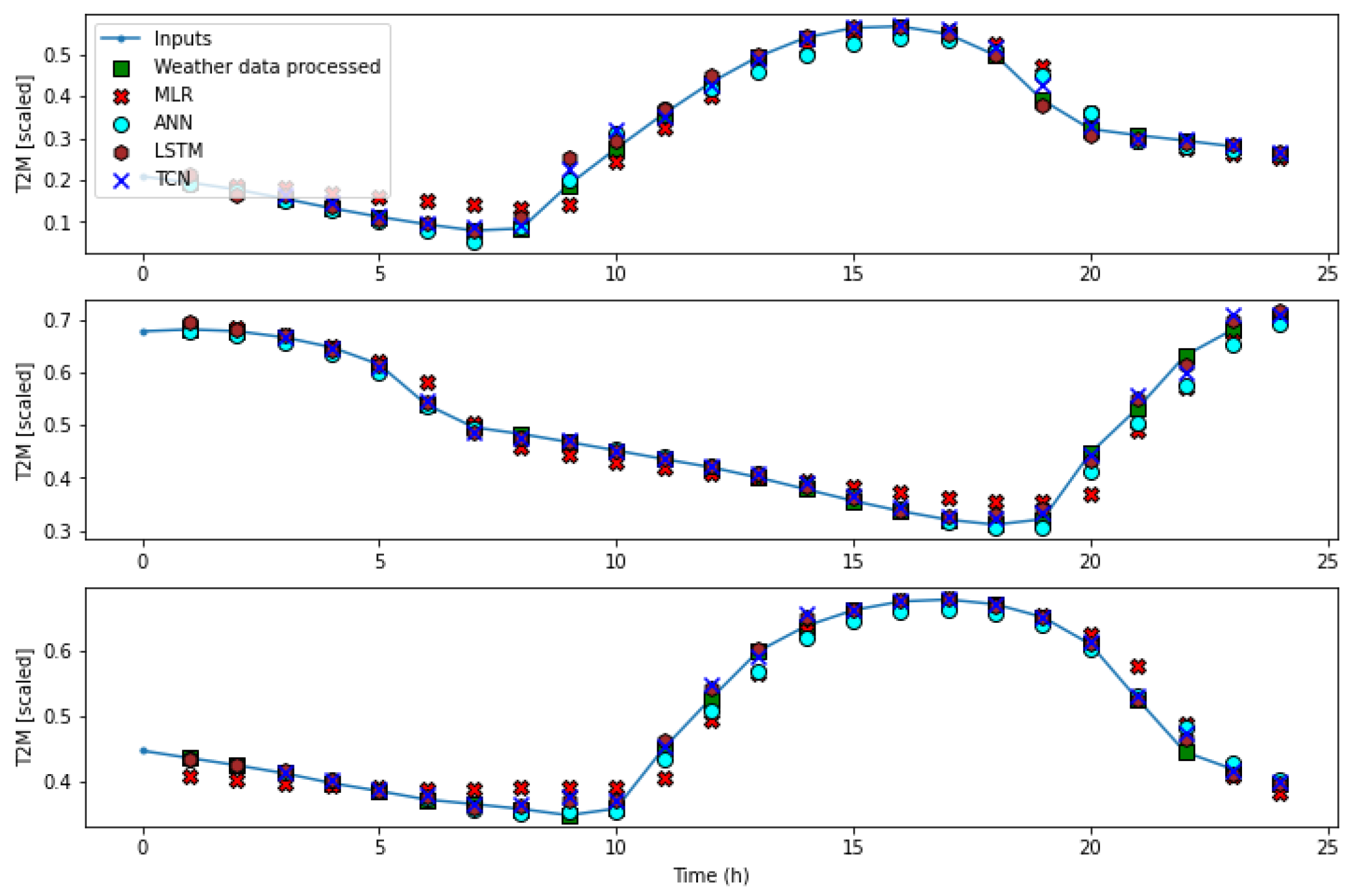

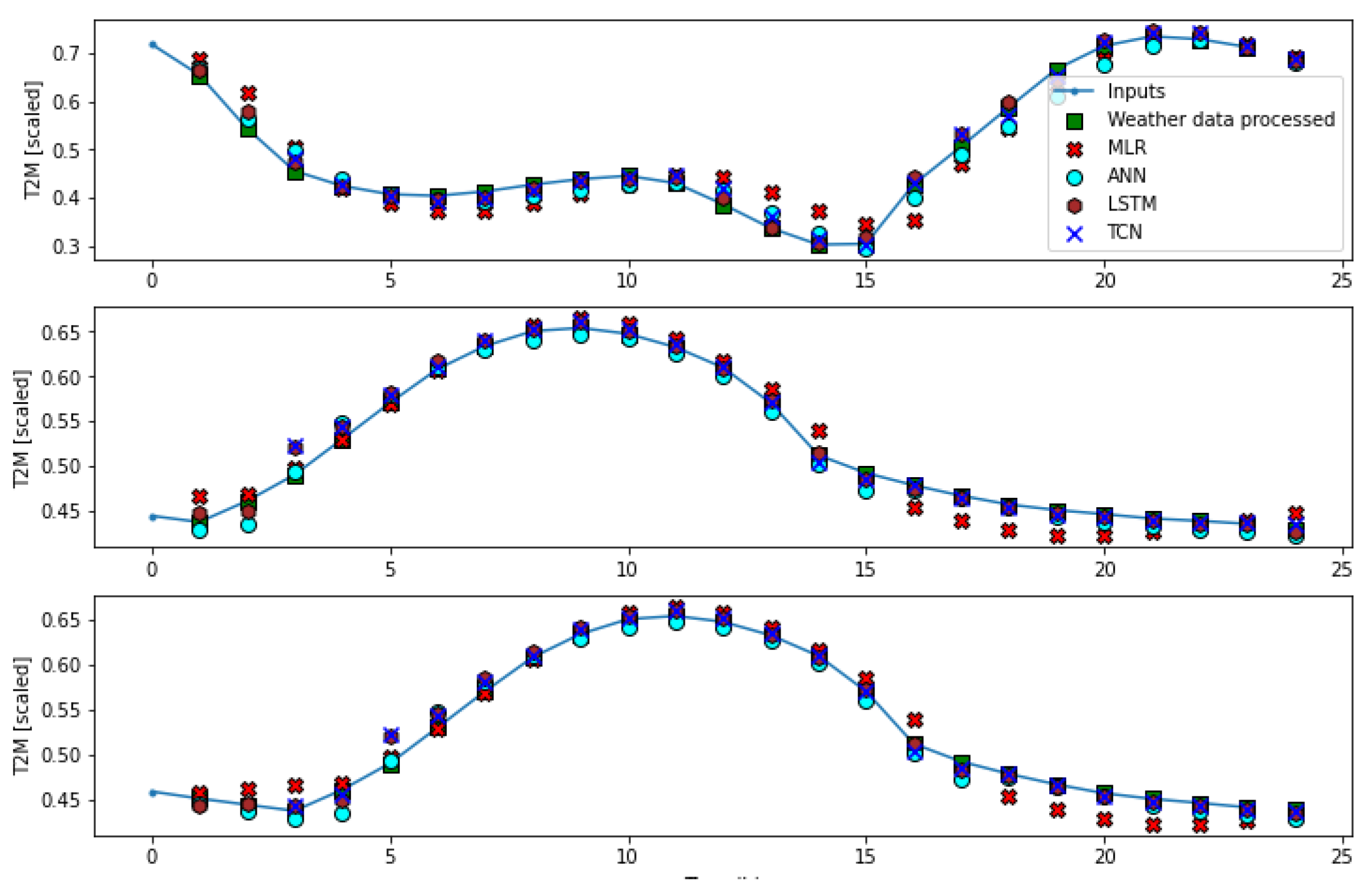

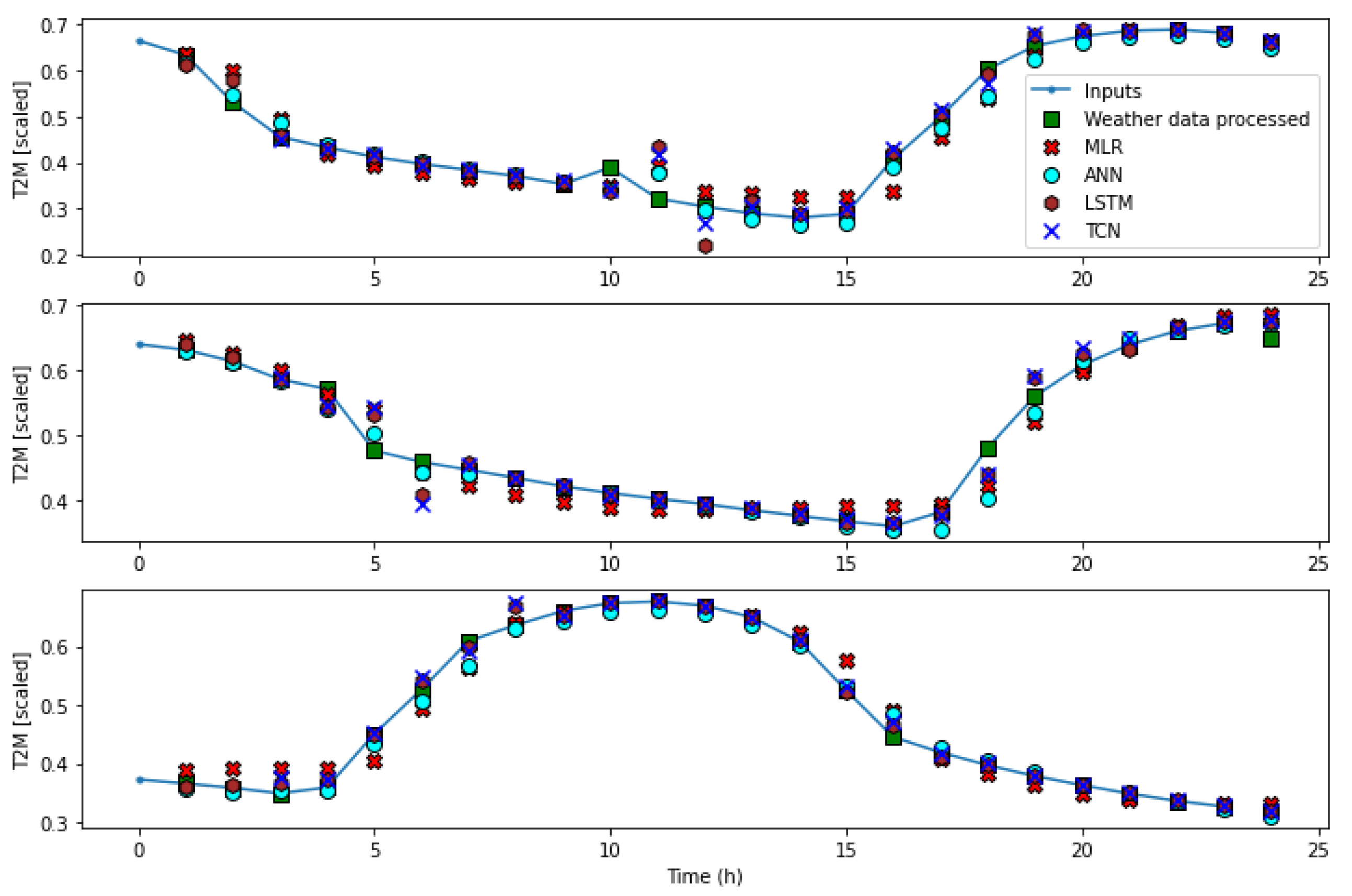

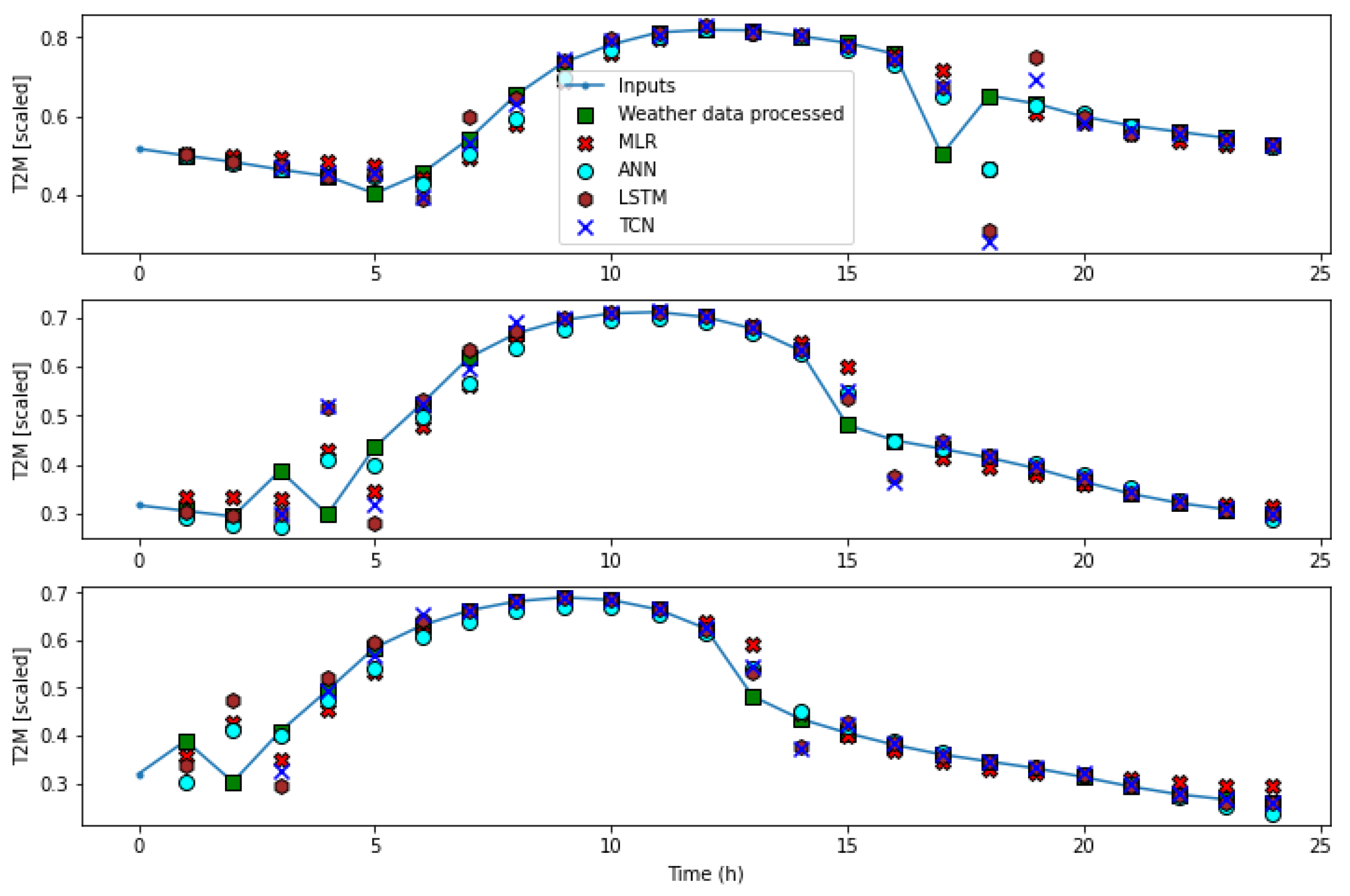

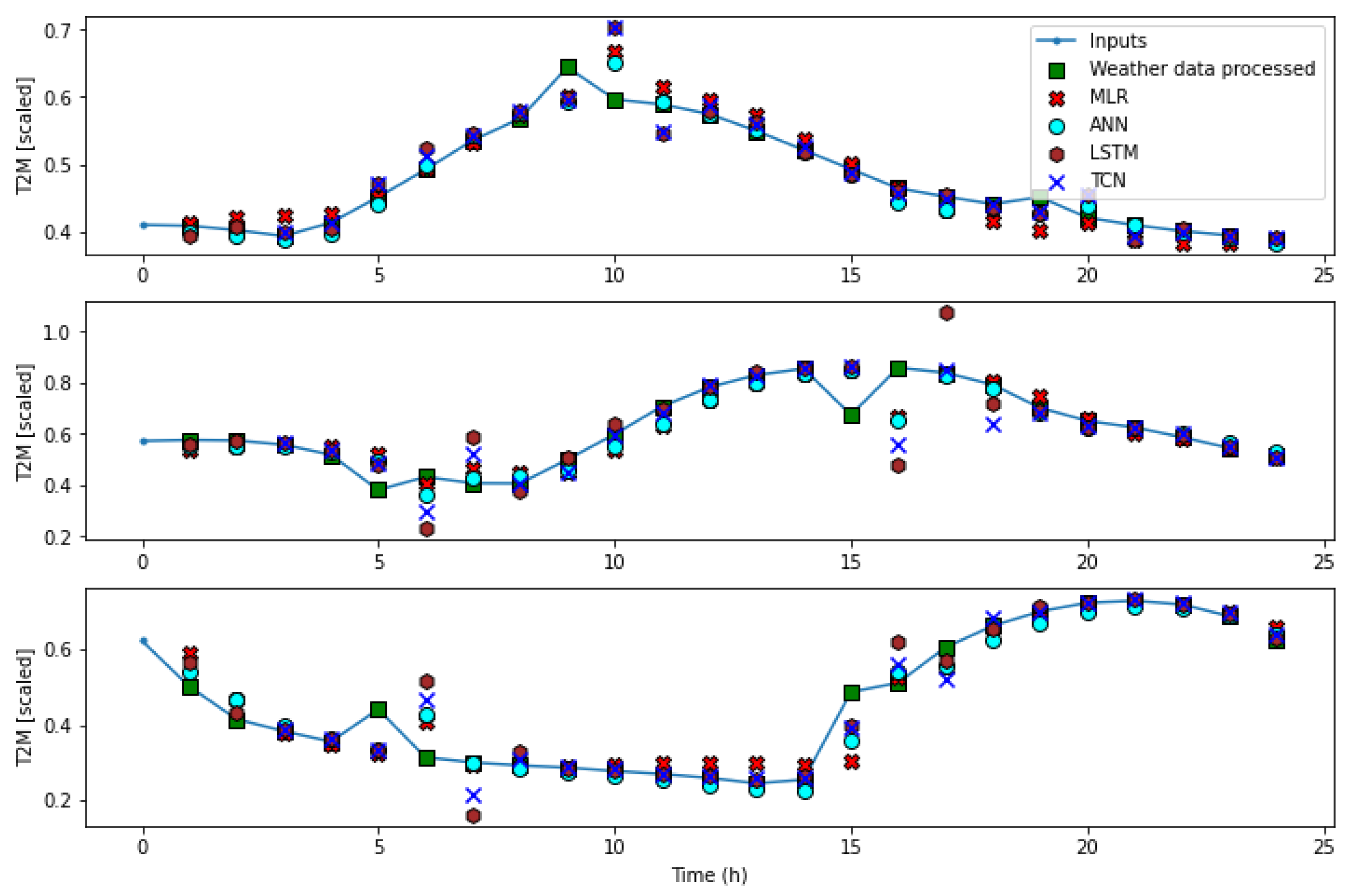

- Step 3 : Forecast using our various models on data cleaned using the ETR imputation method, which previously had a specific anomaly rate (see Figure 7);

- -

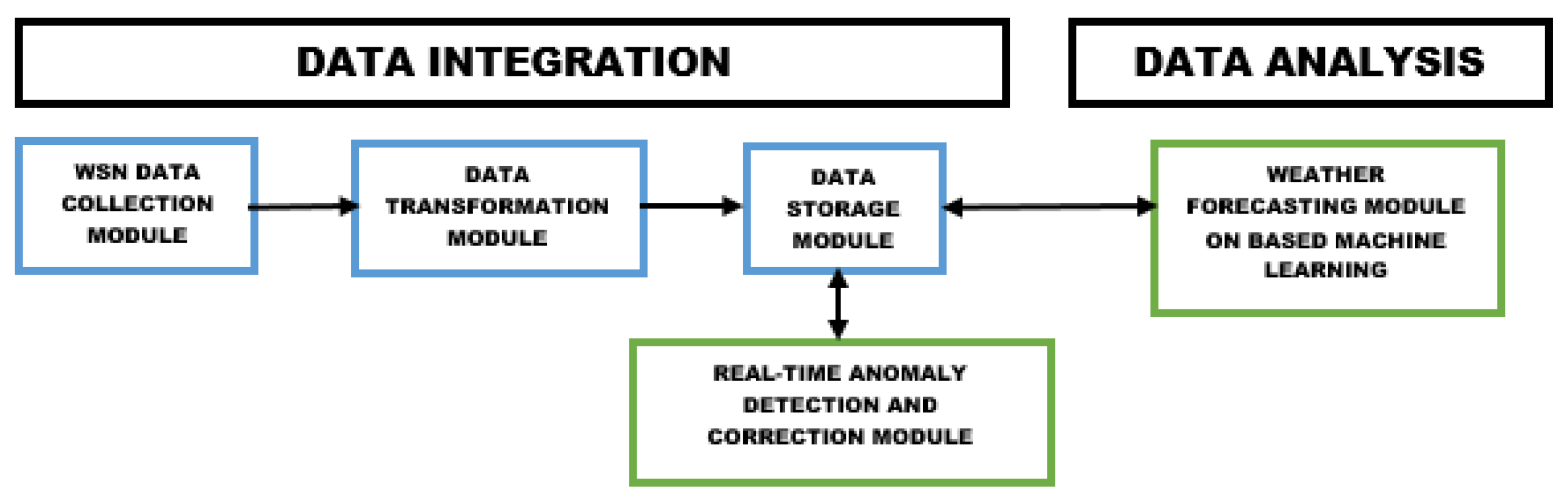

- Step 4 : Proposal for an Architecture of a Forecasting System;

- -

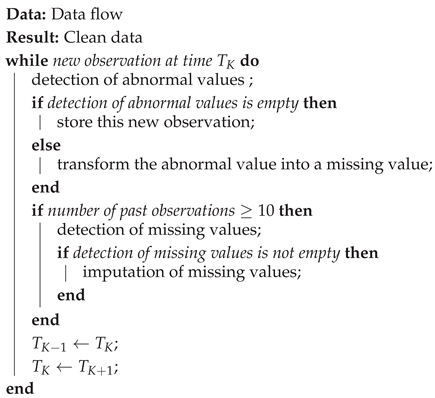

- Step 5 : Proposal of a Real-Time Anomaly Detection and Correction Algorithm in a Weather Forecasting System.

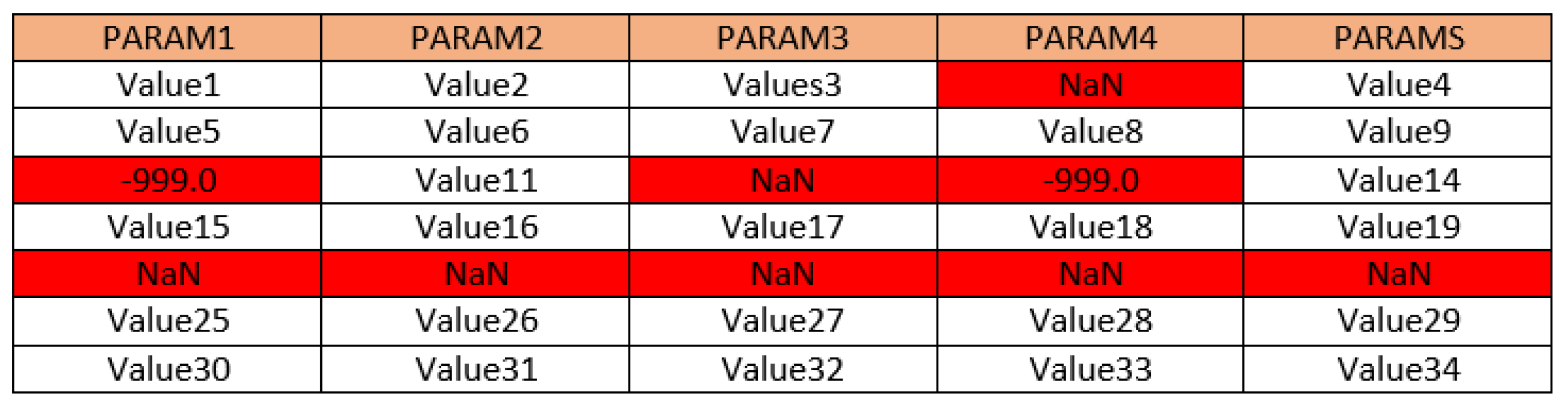

4.2. Anomalies in Weather Data

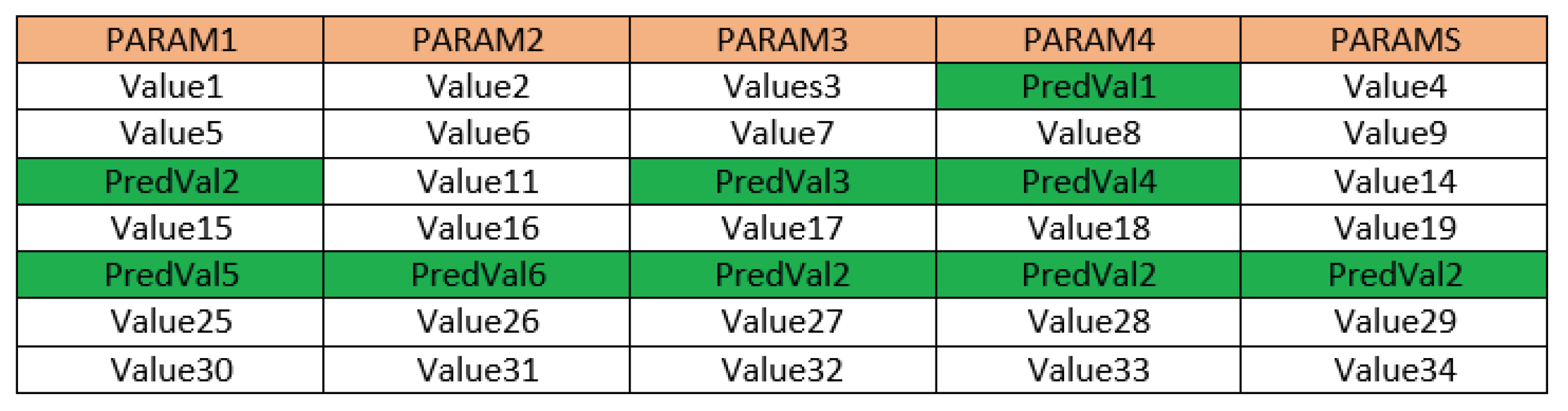

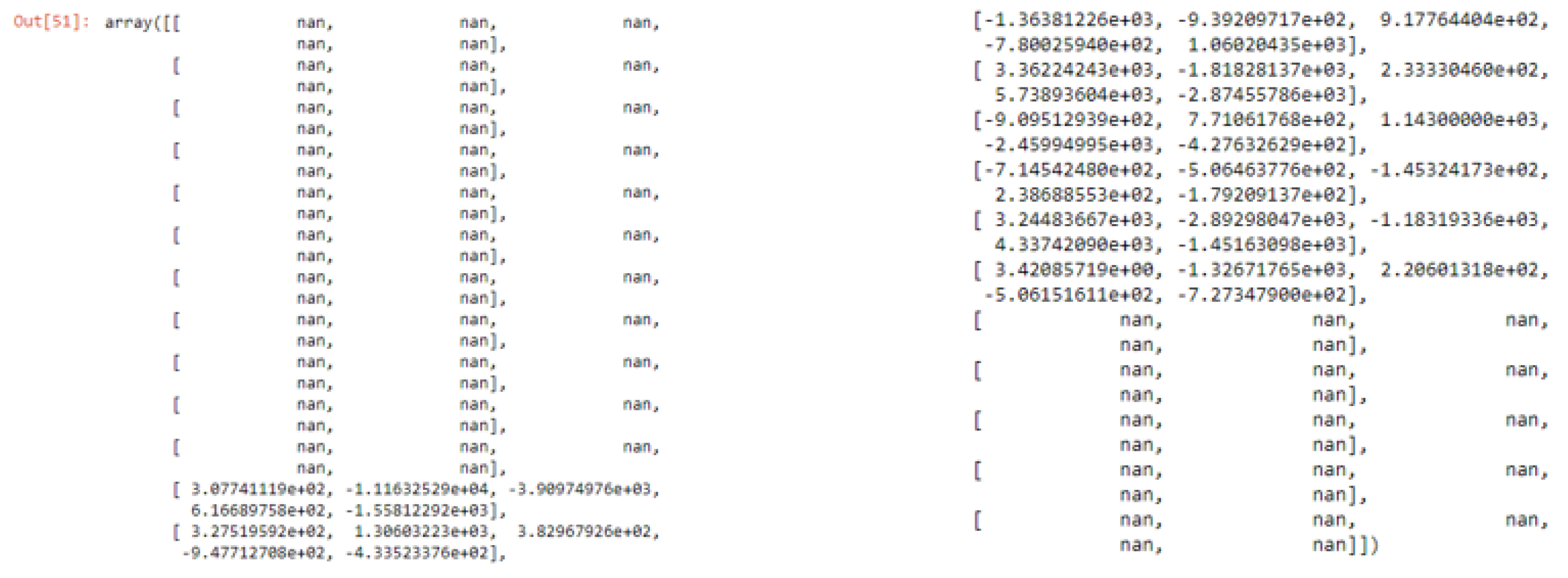

4.3. Imputation Methods

4.3.1. LinearRegressor

4.3.2. BayesianRidge

4.3.3. DecisionTreeRegressor

4.3.4. ExtraTreeRegressor

4.3.5. KNeighborsRegressor

4.3.6. KNNImputer

4.3.7. MICE

4.4. Weather forecasting model based on ML

4.5. Evaluation Metrics

4.6. Tools

5. Results

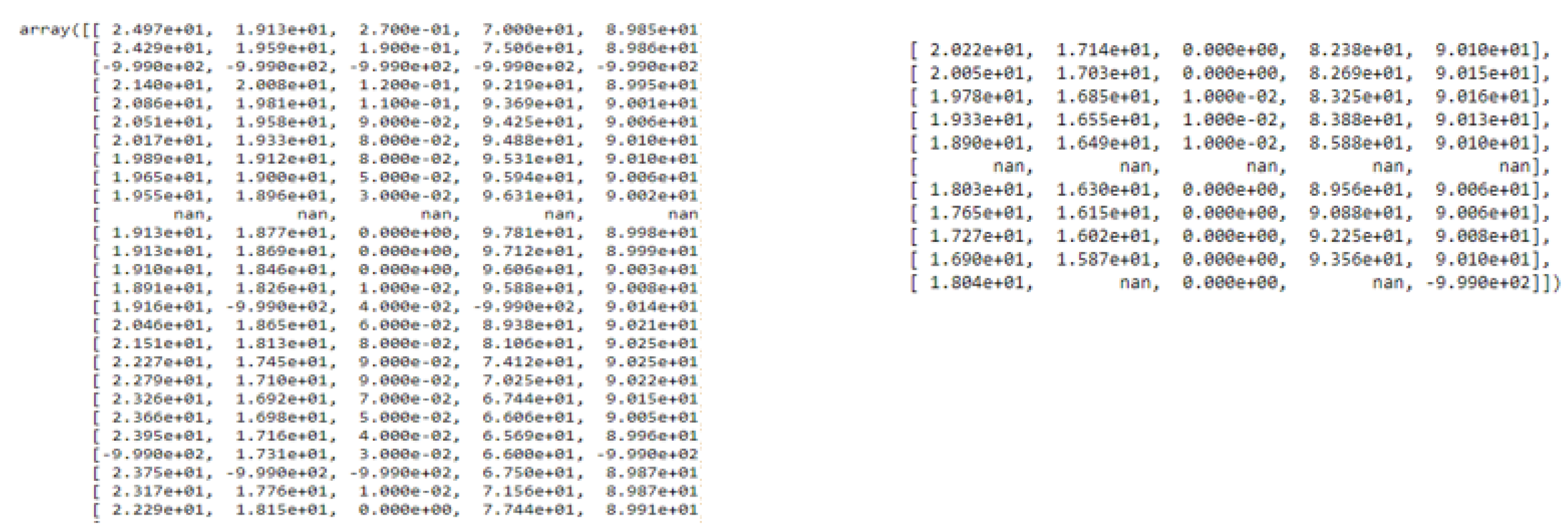

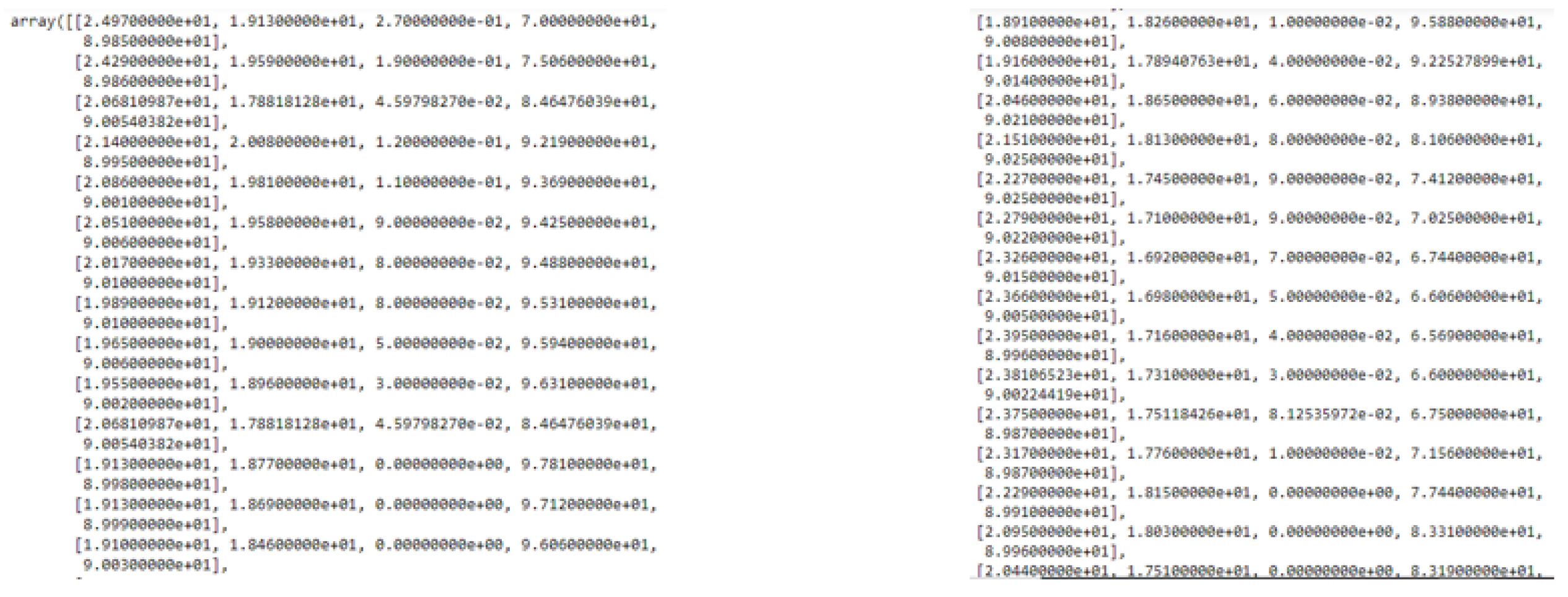

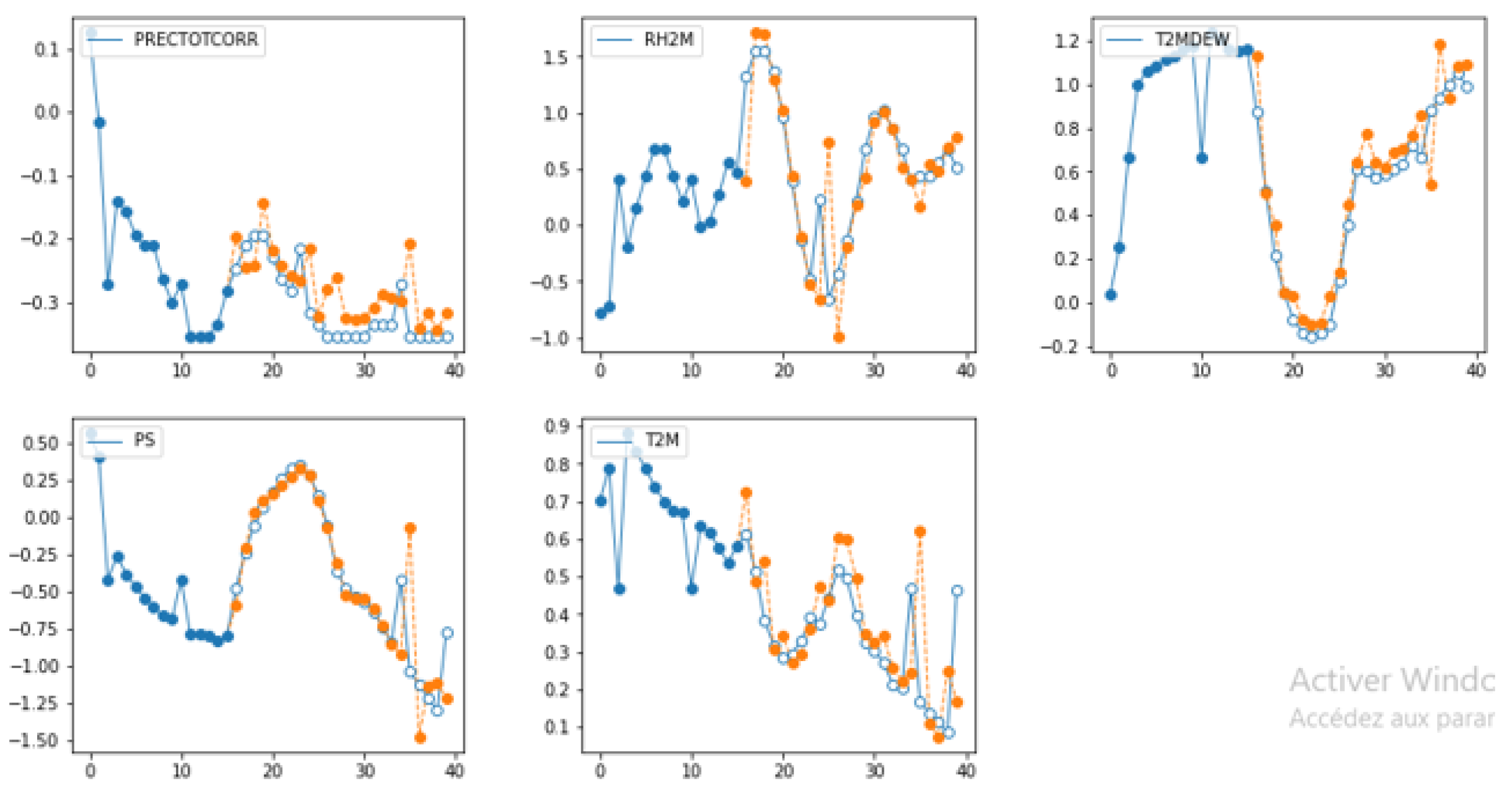

5.1. Forecasting via LSTM Model Taking Data Streams as Input (Uncleaned and Cleaned)

5.1.1. Forecast of Weather Data Containing Anomalies

5.1.2. Forecast of Processed Weather Data

5.2. Selection of the Best Imputaion Model

5.3. Prediction via our Different Forecasting Models on Cleaned Data via ETR Imputation Method

5.4. Proposal for an Architecture of a Weather Forecasting System

5.5. Proposal of a Real-Time Data Cleaning Algorithm

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

References

- Wang, Z.; Mujib, M. The Weather Forecast Using Data Mining Research Based on Cloud Computing. Journal of Physics Conference Series 2016, 910, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.; Mittal, P.; Farheen, S. Real Time Weather Prediction System Using IOT and Machine Learning. IEEE 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min-Ki, L.; Seung-Hyun, M.; Yong-Hyuk, K.; Byung-Ro, M. Correcting Abnormalities in Meteorological Data by Machine Learning. IEEE 2014, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garima, J.; Bhawna, M. A Review on Weather Forecasting Techniques. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer and Communication Engineering 2016, 5, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, V. Traitement des valeurs aberrantes : concepts actuels et tendances générales. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2005, 9, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, G.; Luengo, J.; Herrera, F. Data Preprocessing in Data Mining; Springer : Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London, USA, 2015 pp. 1–315. [CrossRef]

- Daniele, S.; Massimiliano, C.; Milan, A. Boosting a Weather Monitoring System in Low Income Economies Using Open and Non-Conventional Systems: Data Quality Analysis. Sensors 2019, 19, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, M.; Gonzalo, N.; Agnieszka, J.; Yamisleydi, S.; Koen, V. Online learning of windmill time series using Long Short-term Cognitive Networkd. Expert Systems With Applications 2022, 205, 117721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemicheal, T.; Dietterich, G. Anomaly Detection in the Presence of Missing Values for Weather Data Quality Control. ACM 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlène, B.; Aziza, E.O.; Majid, B. A new data imputation technique for efficient used car price forecasting. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) 2024, 15, 2364–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabanita, M.; Tanuja, S. A framework for cloud cover prediction using machine learning with data imputation. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) 2024, 14, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, K. Machine Learning Based Solution for Asymmetric Information in Prediction of Used Car Prices. International Conference on Intelligent Vision and Computing 2023, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, N.A.; Abdul, K. M. M. A Probabilistic Approach for Missing Data Imputation. Complexity 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, P.-L.; Gael, V.; Marine, L.M.; Julie, J.; Jean-Baptiste, P. Benchmarking missing-values approaches for predictive models on health databases. GigaScience 2022, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiahang, L.; ShuXia, G.; RuLin, M.; Jia, H.; XiangHui, Z.; DongSheng, R.; YuSong, D.; Yu, L.; LeYao, J.; Jing, C.; Heng, G. Comparison of the effects of imputation methods for missing data in predictive modelling of cohort study datasets. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2024, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajina, A.; Christiyan, J.K. Prediction of weather forecasting using artificial neural networks. Journal of Applied Research and Technology 2023, 21, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author 1, T. The title of the cited article. Journal Abbreviation 2008, 10, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, V.V.; Reddy, M.M.; Teja, K.S.; Niteesh, C.S.; Babu, B.S. Weather Prediction. IJRASET 2022, 10, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Jin, R. Data-Driven Anomaly Detection Approach for Time-Series Streaming Data. Sensors 2020, 20, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrigs, P. Incidences sécuritaires du changement climatique au Sahel : perspectives politiques. Available online : https://www.wathi.org/incidences-securitaires-du-changement-climatique-au-sahel-perspectives-politiques/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Shruti, D.; Vibhakar, P.; Rohit, M.; Ruchi, D. Machine learning for weather forecasting. 2021, 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Ardilouze, C. , Impact de l’humidité du sol sur la prévisibilité du climat estival aux moyennes latitudes. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OMM. ATLAS DE LA MORTALITÉ ET DES PERTES ÉCONOMIQUES DUES À DES PHÉNOMÈNES MÉTÉOROLOGIQUES, CLIMATIQUES ET HYDROLOGIQUES EXTRÊMES (1970-2019). 2021. Available online: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/1267_Atlas_of_Mortality_FR.pdf (accessed on 01 March 2025).

- BANQUE MONDIALE. Creating an Atmosphere of Cooperation in Sub-Saharan Africa by Strengthening Weather, Climate and Hydrological Services. 2015. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2015/06/02/transforming-weather-climate-and-hydrological-services-in-africa (accessed on 01 March 2025).

- Abdulraheem, M.; Awotunde, J.B.; Adeniyi, A.E.; Oladipo, I.D.; Adekola, S.O. Weather prediction performance evaluation on selected machine learning algorithms. IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence (IJ-AI) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONACC. Etat des lieux du réseau d’observation météorologique dans la Région de l’Adamaoua. 2019, 61–121. Available online: https://files.aho.afro.who.int/afahobckpcontainer/production/files/Profil_ONACC_ADAMAOUA_.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Fente, D.N.; Singh, D.K. Weather Forecasting Using Artificial Neural Network. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Mallick, B. A Review on Weather Forecasting Techniques. IJARCCE 2016, 5, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, A.P.-J.; Carlos, V.-F.; David, T.-P.; George, P.-M. Diseño de una estación meteorológica automática para registrar las variables solar y eólica. Revista Arbitrada Interdisciplinaria Koinonía, 5, 937. [CrossRef]

- Vaumi, J.P.T. Système d’analyse de données pour la prévision des inondations dans les pays en voie de développement. University of Ngaoundere, 19 July 2019.

- NiuBoL. Available online: https://www.niubol.com/All-products/meteorological-station-equipment.html (accessed on 04 January 2025).

- Larraondo, P.R.; Application of machine learning techniques to weather forecasting. University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU. 22 December 2018. Available online: https://addi.ehu.es/bitstream/handle/10810/32532/TESIS_ROZAS_LARRAONDO_PABLO.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Prutor. UNDERSTANDING DATA PROCESSING. 2023.

- Atul, K.; Debajyotti, M. Internet of Things Based Weather Forecast Monitoring System. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2018, 9, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T. The role of Data Processing in Machine Learning. 2023. Available online: https://niveussolutions.com/role-of-data-processing-in-machine-learning/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Heinrigs, P. Incidences sécuritaires du changement climatique au Sahel : perspectives politiques. 2010. Available online: https://www.wathi.org/incidences-securitaires-du-changement-climatique-au-sahel-perspectives-politiques/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Kaya, M.S.; Isler, B.; Abu-Mahfouz, M.A.; Rasheed, J.; Ashammari, A. An Intelligent Anomaly Detection Approach for Accurate and Reliable Weather Forecasting at IoT Edges: A Case Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garima, J.; Bhawma, M. A Review on Weather Forecasting Techniques,» International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer and Communication Engineering. IJARCCE 2016, 5, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalo, M.; Antonio, R.; Helder, D. , Sergio, S.; Hamid, K.; Shabnam, P.; Pedro, M.; Ricardo, H. An Intelligent Weather Station. Sensors 2015, 15, 31005–31022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothapalli, S.; Totad, S.G. A Real-Time Weather Forecasting and Analysis. In Proceedings of Conference: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Power, Control, Signals and Instrumentation Engineering (ICPCSI); 1567–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, A. IoT Based Automated Weather Report Generation and Prediction Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of Conference: 2019 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Communication and Computational Techniques (ICCT). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, H.; Ardhendu, B.; Marcello, T.; Ella, P.; Morteza, G.; Francesco, P.; Yonghuai, L. Temporal convolutional neural (TCN) network for an effective weather forecasting using time-series data from the local weather station. Soft Computing 2020, 2020, 16453–16482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, S.; Tao, H.; Claude, M. Temperature Anomaly Detection for Electric Load Forecasting. International Journal of Forecasting 2020, 36, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruti, D.; Vibhakar, P.; Rohit, M.; Ruchi, D. Machine learning for weather forecasting. 2021, 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Adela, B.; Alin, G.V.; Simona-Vasilica, O. Anomaly Detection in Weather Phenomena: News and Numerical Data-Driven Insights into the Climate Change in Romania’s Historical Regions. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems 2024, 134, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINEPAT. ELABORATION DU SCHEMA REGIONAL D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE DU TERRITOIRE DE L’ADAMAOUA : ATLAS CARTOGRAPHIQUE DE L’ADAMAOUA. Le groupement AGORA Consulting, CID, MINEPAT : Cameroon, 2018; pp. 1–45. Available online: https://minepat.gov.cm/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/1.1.-SRADDT-AD-Diagnostic-territorial-Atlas-cartographique.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Sadio, F.H. LE TOURISME DANS LE DEPARTEMENT DE LA VINA (ADAMAOUA-CAMEROUN) : Mythe ou Réalité ?. Géographie et Pratique du Développement Durable, Université de Ngaoundéré, Cameroun, 2012. Available online: https://www.memoireonline.com/05/20/11825/m_Le-tourisme-dans-le-departement-de-la-vina-adamaoua-cameroun–mythe-ou-realite-0.html (accessed on 01 July 2025).

- Michel, T. Paysage géomorphologique, patrimoine socio-culturel et développement sur les hautes terres de l’Adamaoua au Cameroun. Espaces tropicaux 2003, 18, 67–75. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/etrop_1147-3991_2003_act_18_9_1108 (accessed on 02 July 2025).

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Analyse statistique avec données manquantes, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tlamelo, E.; Thabiso, M.; Dimane, M. , Thabo, S., Banyatsang, M.; Oteng, T. A survey on missing data in machine learning. Journal of Big Data 2021, 8, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, G.; Cot, M.; Mary, J.-Y. Multiple imputation of missing at random data: General points and presentation of a Monte-Carlo method. Revue d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique 2009, 57, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyant, A.; Guemann, M.; Malgoyre, A. Epidemiological study of major amputations of upper and lower limbs in France. Kinésithérapie, la Revue, 2023; 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Elizaberth, A.S.; David, B.A. Multiple Imputation: A Flexible Tool for Handling Missing Data. JAMA 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.-B. Chapiter 1 Introduction : From Batch to Online Machine Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alban, F.; Marc, B.; Patrick, L.; Massimo, B.; Quentin, M. A comparison of combined data assimilation and machine learning methods for offline and online model error correction. Journal of Computational Science 2021, 55, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Imputation | 1% | 5% | 8% | 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| models | rate | rate | rate | rate |

| LR | ||||

| MICE | ||||

| KNNI | ||||

| BR | ||||

| DTR | ||||

| ETR | ||||

| KNR | ||||

| Interval |

| Imputation | 1% | 5% | 8% | 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| models | rate | rate | rate | rate |

| LR | ||||

| MICE | ||||

| KNNI | ||||

| BR | ||||

| DTR | ||||

| ETR | ||||

| KNR | ||||

| Interval |

| ML-based weather forecasting models | 0% rate | 1% rate | 5% rate | 8% rate | 10% rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLR | |||||

| ANN | |||||

| LSTM | |||||

| TCN | |||||

| Interval |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).